Epidural analgesia (EA) is clearly the most effective form of pain relief during labour.1 But various unwanted side effects are associated with its use,2 including longer labour; increased incidence of maternal fever (with associated increase in use of antibiotics for mothers and newborns); and increased rates of operative vaginal delivery and perineal trauma,2 such as more third- and fourth-degree tears.3,4

The 2000 Cochrane meta-analysis2 that compared EA with narcotics did not show increased rates of cesarean section (CS) associated with EA. For many practitioners this came as a surprise; in practice EA certainly seemed to increase rates of CS, especially when used before the active phase of labour. Earlier studies5,6 had shown a modest increase in rates of CS when EA was compared with other methods of analgesia. One trial showed such a large effect that the trial had to be stopped.6

Departmental quality improvement

Because use of EA varied greatly among physicians in our department, we began a series of quality-improvement activities. We found that physicians who used EA 40% of the time or less had a CS rate of 14.8% for nulliparous patients, while those who used EA 71% to 100% of the time had a CS rate of 23.4%. Multiparous women were unaffected by their physicians’ use of EA. We did not know why this was so, but we knew from the literature that using EA early in labour, before the fetus is well down in the pelvis, could cause extension of the fetal head or not allow for flexion, and this would interfere with rotation and descent.2,7,8 We did find that physicians in our department who used EA frequently had more patients with malpositions (occiput posterior and occiput transverse), had patients who required more augmentation, had fewer patients with spontaneous births, and had more CS deliveries.9

Our results were similar to those of a natural experiment at a nearby community hospital. Their rate of EA was 15.4% compared with our rate of 67.2%. We reported that, for comparable women, the odds of having a CS at our tertiary centre were 3.4 times greater (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.1 to 5.4) than at the community hospital. Maternal age, more advanced cervical dilation on admission, and use of EA were the primary factors associated with the difference in CS rates. Use of EA had the largest effect.10

These studies made it difficult to accept the results of the 2000 Cochrane meta-analysis, which concluded that EA did not raise rates of CS. In fact, it appeared that increasing use of EA was transforming birth. A recent report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information indicated that 4 of 5 Canadian women giving birth received 1 or more major obstetrical intervention, with EA high on the list (as high as 65% in major urban areas).11 Yet, as a society and as professionals, we seem reluctant to acknowledge this change and its effect on the birthing environment.12

The Cochrane meta-analysis

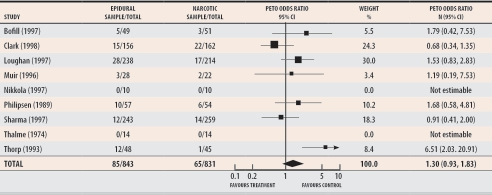

I then decided to look more closely at the individual studies that made up the 2000 Cochrane meta-analysis addressing the effect of EA (Figure 1).2 While made up of a group of very heterogeneous trials, the meta-analysis demonstrated that, compared with narcotic use, EA increased the first stage of labour by 4.3 hours; Sharma et al,13 who conducted one of the studies included in the meta-analysis, demonstrated an increase of only 1 hour. Similarly, the second stage of labour was increased by 1.4 hours; Sharma et al reported an increase of only 19 minutes. Malpositions were found in 15% of patients who received EA but in only 7% of patients who received narcotics. Oxytocin augmentation of labour was found in 52% of women who received EA and in 7% of women who received narcotics. In the Sharma study, those values were less extreme: 33% versus 15%. Instruments were used in 27% of deliveries versus 16%, respectively. In a meta-analysis by Lieberman and O’Donoghue,14 perineal trauma doubled among patients receiving EA, due in part to an increase in the use of forceps and vacuum. In the Cochrane2 and Lieberman and O’Donoghue14 meta-analyses, maternal fever was dramatically higher in the epidural versus narcotic arms, 24% and 6% respectively, with a relative risk of anywhere from 4 to 70.

Figure 1.

Cochrane meta-analysis of epidural and narcotic analgesia shows that epidural analgesia does not increase rates of cesarean section

Test for heterogeneity: chi-square = 12.24, df = 6 (P = .0569); Test for overall effect: Z = 1.54 (P = .12); Data from Howell.2

Why was there no increase in cesarean section?

It was hard to understand why, if EA clearly increased abnormalities of labour, rates of CS did not also increase. The study by Sharma and colleagues13 is the key study that led to the Cochrane review’s conclusion that EA did not increase rates of CS. This was the largest study in the meta-analysis and clearly demonstrated no increase in CS; because of its large numbers, Sharma and colleagues’ trial overwhelmed the other results. Sharma’s team comes from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, Tex, where the hospital CS rate was only 12%. Most importantly, the subjects in the trial were randomized at more than 4-cm cervical dilation—the active phase of labour. According to the Cochrane data, the rate of CS for both groups in the study by Sharma and colleagues was only 5%. Clark et al15 and Loughnan et al16 also randomized most of their (many) patients after 4-cm dilation; their CS rates were 14% in the narcotics group and 10% in the EA group and 13% in the narcotics group and 12% in the EA group, respectively. Again, rates of CS were so low as to be unable to show a difference. Though the Cochrane meta-analysis was not set up to address this issue, what it actually shows is that EA administered in the active phase of labour does not increase rates of CS.

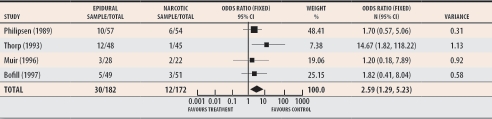

But our sensitivity analysis (Figure 2) demonstrates that when the studies by Clark,15 Loughnan,16 and Sharma,13 who also randomized patients in the active phase of labour, are excluded from the meta-analysis, the odds ratio for the remaining studies is 2.59 (95% CI 1.29 to 5.23), indicating that for studies that randomized most of their patients before 4-cm dilation, CS is more than twice as likely when EA is used than when other types of analgesia are used.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of the studies in the Cochrane meta-analysis of epidural and narcotic analgesia that randomized patients early (< 4-cm cervical dilation).

Odds ratio of 2.59 indicates that under those conditions epidural analgesia more than doubles rates of cesarean section.

Test for heterogeneity: chi-square = 4.08, df = 3 (P = .25); Test for overall effect: z = 2.66 (P = .008); Data from Howell.2

External validity

The study by Sharma et al13 and other similar studies that randomized women late in labour would better illustrate that women should be encouraged to try to reach at least 4- to 5-cm dilation before EA is used. Ideally the Cochrane review could have constructed 2 meta-analytical strata, 1 before and 1 after 4-cm dilation.

A recent example of the misuse or misinterpretation of randomized controlled trials of EA17 caught the attention of the international press. The reported study was of “neuraxial analgesia,” an obfuscating term. The author, the editorialist,18 and the press reported that women need not worry that early EA will lead to increased likelihood of CS. This claim is unjustified by the research reported. This trial was not about early use of EA; it was about 2 methods of helping women with the pain of early labour. At first request for analgesia, women in the so-called epidural group received intrathecal fentanyl, and an epidural catheter was placed but not used. Women in the narcotics group received hydromorphone. At that point 75% of women in both groups had received oxytocin augmentation—a rate higher than can be generalized. On second request for pain relief, two thirds of the women in both groups were in the active phase of labour. At this advanced stage, women in the fentanyl-epidural group received low-dose EA. Women in the narcotic group received hydromophone intramuscularly. This trial again is misleading because it fails to emphasize that most women were in the active phase of labour at randomization. This study, like the others randomizing late, has shown only that when women’s latent-phase pain is managed with intrathecal narcotics or other pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic means, EA in the active phase of labour does not increase the CS rate. The role of early EA in contributing to CS increase has yet to be studied in a controlled trial, though this sensitivity analysis of the Cochrane review suggests that early EA does increase rates of CS.

Collateral damage

The Cochrane meta-analysis of EA has inadvertently increased use of EA, and has therefore increased continuous electronic fetal monitoring; kept more women in bed (usually with an intravenous drip); and led to more instrumentation, more perineal trauma, an increase in the CS rate, and, likely, more feelings of failure among mothers. It will also lead, because of the increase in CS, to an increase in problems with placentas in future pregnancies (previa, accreta, percreta, abruption),19 infertility,20 and ectopic pregnancies.19 This is unexpected collateral damage that contributes to overuse of technology during childbirth. It has even led some to suggest that, since childbirth is already so unnatural, CS on request is not such an unreasonable idea—a surgical solution for a non-surgical problem.21-23

The 2005 Cochrane meta-analysis24 was augmented by 3 new studies,25-27 2 of which had such low baseline rates of CS that the effect of EA on CS could never be demonstrated.25,26 One study25 evaluated the combined spinal-epidural method, similar to Wong et al,17 but suffered from very high crossover rates between trial groups, and 2 studies randomized patients before 4-cm dilation.26,27 When these studies are appropriately removed from the new meta-analysis, the result remains exactly the same: early EA more than doubles the CS rate. Surprisingly, the new Cochrane review provided extensive sensitivity analyses for many issues but none by timing of EA administration.

Conclusion

Contrary to the conclusion of the Cochrane meta-analysis of EA compared with narcotic analgesia, EA given before the active phase of labour more than doubles the probability of receiving a CS. If given in the active phase of labour, EA does not increase rates of CS. Meta-analysis can be helpful and timesaving for busy practitioners, but we need to be vigilant about which studies get into the meta-analyses and ask ourselves if they make clinical sense. And, unfortunately, we need to continue to read the individual studies that make up meta-analyses—especially if they are likely to actually change practice—to determine whether study conditions represent our clinical reality.

Acknowledgments

I thank Peter von Dadelszen, perinatologist at Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia, for assistance with the sensitivity analysis of Cochrane meta-analysis; Andrew Kotaska, obstetrical resident at Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia; and Murray Enkin, Professor Emeritus of Obstetrics and Gynecology at McMaster University, for criticism and support.

Biography

Dr Klein is Professor Emeritus of Family Practice and Pediatrics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and is certified in pediatrics, neonatal-perinatal medicine, and family medicine.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed in editorials are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

References

- 1.Leeman L, Fontaine P, King V, Klein MC, Ratcliffe S. The nature and management of labor pain: part II. Pharmacologic pain relief. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1115–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell CJ. Epidural versus non-epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. CD000331. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Robbins JM, Kaczorowski J, Jorgensen SH, Franco ED, et al. Relationship of episiotomy to perineal trauma and morbidity, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic floor relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:591–598. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein MC, Janssen PA, MacWilliam L, Kaczorowski J, Johnson B. Determinants of vaginal-perineal integrity and pelvic floor functioning in childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70506-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morton SC, Williams MS, Keeler EB, Gambone JC, Kahn KL. Effect of epidural analgesia for labor on the cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(6):1045–1052. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199406000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorp JA, Hu DH, Albin RM, McNitt J, Meyer BA, Cohen GR, et al. The effect of intrapartum epidural analgesia on nulliparous labor: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:851–858. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90015-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoult IT, MacLennan AH, Carrie LE. Lumbar epidural analgesia in labour: relation to fetal malposition and instrumental delivery. BMJ. 1977;1:14–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6052.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman E, Cohen A, Lang JM, D’Angostino R, Jr, Datta S, Frigoletto FD., Jr The association of epidural anesthesia with cesarean section in low risk women [abstract]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:276. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein MC, Grzybowski S, Harris S, Liston R, Spence A, Le G, et al. Epidural analgesia use as a marker for physician approach to birth: implications for maternal and newborn outcomes. Birth. 2001;28(4):243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen PA, Klein MC, Soolsma JH. Differences in institutional cesarean delivery rates—the role of pain management. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(3):217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Giving birth in Canada: a regional profile. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reime B, Klein MC, Kelly A, Duxbury N, Saxell L, Liston R, et al. Do maternity care provider groups have different attitudes towards birth? BJOG. 2004;111(12):1388–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Ramin SM, Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Cesarean delivery: a randomized trial of epidural versus patient-controlled meperidine analgesia during labor. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:487–494. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman E, O’Donoghue C. Unintended effects of epidural analgesia during labor: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl Nature):31–68. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark A, Carr D, Loyd G, Cook V, Spinnato J. The influence of epidural analgesia on cesarean delivery rates: a randomized, prospective clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(6 Pt 1):1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loughnan BA, Carli F, Romney M, Dore CJ, Gordon H. Randomized controlled comparison of epidural bupivacaine versus pethidine for analgesia in labour. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(6):715–719. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM, McCarthy RJ, Sullivan JT, Diaz NT, et al. The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early versus late in labor. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):655–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camann W. Pain relief during labor. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):718–720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemminki E, Merilainen J. Long-term effects of cesarean sections: ectopic pregnancies and placental problems. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemminki E. Impact of caesarean section on future pregnancy—a review of cohort studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1996;10(4):366–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannah ME. Planned elective cesarean section: a reasonable choice for some women? CMAJ. 2004;170:813–814. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1032002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein MC. Elective cesarean section [letter]. CMAJ. 2004;171:14–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein MC. Quick fix culture: the cesarean-section-on-demand debate. Birth. 2004;31(3):161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Howell C. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005. CD00331. pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dickinson JE, Paech MJ, McDonald SJ, Evans SF. The impact of intrapartum analgesia on labour and delivery outcomes in nulliparous women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. pp. 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Sharma SK, Alexander JM, Messick G, Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Wiley J, et al. Cesarean delivery: a randomized trial of epidural analgesia versus intravenous meperidine analgesia during labor in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology. pp. 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Jain S, Arya VK, Gopalan S, Jain V. Analgesic efficacy of intramuscular opioids versus epidural analgesia in labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]