Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess challenges in providing palliative care in long-term care (LTC) facilities from the perspective of medical directors.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional mailed survey. A questionnaire was developed, reviewed, pilot-tested, and sent to 450 medical directors representing 531 LTC facilities. Responses were rated on 2 different 5-point scales. Descriptive analyses were conducted on all responses.

SETTING

All licensed LTC facilities in Ontario with designated medical directors.

PARTICIPANTS

Medical directors in the facilities.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Demographic and practice characteristics of physicians and facilities, importance of potential barriers to providing palliative care, strategies that could be helpful in providing palliative care, and the kind of training in palliative care respondents had received.

RESULTS

Two hundred seventy-five medical directors (61%) representing 302 LTC facilities (57%) responded to the survey. Potential barriers to providing palliative care were clustered into 3 groups: facility staff’s capacity to provide palliative care, education and support, and the need for external resources. Two thirds of respondents (67.1%) reported that inadequate staffing in their facilities was an important barrier to providing palliative care. Other barriers included inadequate financial reimbursement from the Ontario Health Insurance Program (58.5%), the heavy time commitment required (47.3%), and the lack of equipment in facilities (42.5%). No statistically significant relationship was found between geographic location or profit status of facilities and barriers to providing palliative care. Strategies respondents would use to improve provision of palliative care included continuing medical education (80.0%), protocols for assessing and monitoring pain (77.7%), finding ways to increase financial reimbursement for managing palliative care residents (72.1%), providing educational material for facility staff (70.7%), and providing practice guidelines related to assessing and managing palliative care patients (67.8%).

CONCLUSION

Medical directors in our study reported that their LTC facilities were inadequately staffed and lacked equipment. The study also highlighted the specialized role of medical directors, who identified continuing medical education as a key strategy for improving provision of palliative care.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer les facteurs qui, de l’avis des directeurs médicaux, font obstacle à la prestation de soins palliatifs dans les établissements de soins de longue durée (SLD).

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête postale transversale. Un questionnaire a été élaboré, révisé et préalablement testé, puis adressé à 450 directeurs médicaux représentant 531 établissements de SLD. Les réponses ont été cotées sur 2 échelles différentes comportant 5 points. Toutes les réponses ont fait l’objet d’une analyse descriptive.

CONTEXTE

Tous les établissements de SLD autorisés en Ontario avec un directeur médical désigné.

PARTICIPANTS

Directeurs médicaux des établissements.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Caractéristiques démographiques et types de pratique des médecins et des établissements, importance des obstacles à la prestation des soins palliatifs, stratégies susceptibles d’améliorer ces soins et type de formation en soins palliatifs reçue par les répondants.

RÉSULTATS

Des réponses ont été obtenues de 275 directeurs médicaux (61%) représentant 302 établissements de SLD (57%). Les obstacles potentiels à la prestation de soins palliatifs étaient regroupés sous 3 thèmes: capacité du personnel local à fournir des soins palliatifs, formation et support, et accès à des ressources externes. Les deux tiers des répondants (67,1%) considéraient que le manque d’effectifs dans leur établissement constituait un obstacle important à la prestation de soins palliatifs. Parmi les autres facteurs, mentionnons les honoraires insuffisants consentis par l’Assurance-santé de l’Ontario (58,5%), l’important investissement de temps nécessaire (47,3%) et le manque d’équipement dans l’établissement (42,5%). On n’a pas observé de relation significative entre la situation géographique ou financière des établissements et les obstacles à la prestation de soins palliatifs. Les stratégies suggérées par les répondants pour améliorer la prestation de soins palliatifs incluaient la formation médicale continue (80,0%), des protocoles pour évaluer et surveiller la douleur (77,7%), des stratégies pour augmenter les tarifs d’honoraires pour la prise en charge des résidants requérant des soins palliatifs (72,1%), du matériel éducatif pour le personnel de l’établissement (70,7%), et la mise en place de directives de pratique portant sur l’évaluation et le traitement des patients nécessitant ces soins (67,8%).

CONCLUSION

Les directeurs médicaux consultés ont déclaré que leur établissement manquait de personnel et d’équipement. Cette étude a aussi mis en lumière le rôle particulier des directeurs médicaux qui estiment que l’éducation médicale continue est une stratégie clé pour améliorer la dispensation des soins palliatifs.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Medical directors of long-term care facilities, usually family physicians, increasingly face problems in providing palliative care as more and more residents die in facilities rather than in hospitals.

This survey of medical directors in Ontario highlighted barriers to providing palliative care that included inadequate facility staffing and staff’s lack of training in palliative care, directors’ own lack of knowledge or opportunity to obtain consultation, and the inadequate fee schedule given the heavy time commitments required for palliative care.

Medical directors suggested better training for themselves and their staff in palliative care, practice guidelines that would be available as resources, and better access to specialist consultation as ways to improve palliative care.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Les directeurs médicaux d’établissements de soins de longue durée, qui sont généralement des médecins de famille, ont de plus en plus de difficulté à fournir des soins palliatifs étant donné qu’un nombre croissant des pensionnaires meurent dans leurs établissements plutôt qu’à l’hôpital.

Cette enquête auprès de directeurs médicaux d’Ontario a permis d’identifier des obstacles à la prestation des soins palliatifs, tels qu’un manque d’effectifs et une formation insuffisante du personnel en soins palliatifs, un manque de connaissances du directeur lui-même et la difficulté pour lui d’obtenir des consultations, et des honoraires insuffisants compte tenu des longues heures exigées par ce type de soins.

Comme moyen d’améliorer les soins palliatifs, les directeurs ont suggéré une meilleure formation en soins palliatifs pour eux et leur personnel, la disponibilité de directives de pratique et un meilleur accès à des consultations auprès de spécialistes.

Older adults are more frequently dying in long-term care (LTC) facilities.1,2 As a result, health care providers working in LTC facilities are increasingly challenged by the complex decisions associated with caring for dying residents. Results of studies indicate that the care provided to dying LTC residents is inadequate,3,4 that pain and symptoms are managed poorly,5-8 that communication among service providers and with family members is poor,9,10 that there are unnecessary hospitalizations,6,11 and that caregivers need better education.12-15

Medical practice in LTC facilities is different from that in other practice locations. These facilities rely on community-based attending physicians to provide medical care to LTC residents. While attention must be directed to acute problems and chronic disabilities, dementia and associated behavioural issues must also be managed. Also, medical care is provided within a regulatory, institutional, and reimbursement environment where attending physicians are expected to collaborate with facility staff and families to integrate the approach to care.5,16-21

Physicians are challenged to integrate and balance palliative care with chronic and acute care. Attending physicians are responsible for coordinating residents’ care, anticipating problems that might lie ahead, and providing possible solutions for coping with these problems. Physicians draw from their own experience as well as from the experience of residents, their families, and facility staff. A coordinating nurse and an attending physician form the core team in caring for a dying resident.5,16,18,19,22

In Ontario, LTC facilities provide care and services to patients whose needs cannot be met in the community. Facilities are designed for people who need on-site, 24-hour nursing services and daily personal assistance and who could be at risk of harm in their current homes. The provincial government pays for physician, nursing, and personal care services; residents pay their accommodation costs. There are both for-profit and non-profit LTC facilities.

Medical directors are responsible for monitoring and evaluating the medical care and services provided in facilities and for taking action when standards are not met. They also provide advice to administrators in the areas of developing, implementing, and evaluating services and policies. Medical directors are usually also directly responsible for primary care of some residents.23

Little is understood about the perspective of physicians who care for dying patients in LTC facilities.10,24,25 Published research has identified the difficulty physicians have in interpreting changes in residents’ status and determining when the goals of care should be shifted to emphasize palliation.25 The purpose of this study was to assess challenges in caring for dying residents in LTC facilities from the perspective of medical directors. The study also elicited strategies to assist medical directors in providing palliative care. This study is the only one that has attempted to undertake a large-scale survey on this issue and is the first such survey to be conducted in Canada.

METHOD

Design and participants

All licensed LTC facilities in Ontario with a designated medical director were considered eligible to participate in the cross-sectional mailed survey. Five hundred thirty-one facilities were determined to be eligible, and 450 physicians were identified as medical directors of these facilities (386 physicians were medical directors of 1 facility, 51 of 2 facilities, and 13 of 3 or more facilities).

Survey questionnaire

Development of the survey questionnaire followed accepted questionnaire construction procedures.26 A literature review provided initial direction on development of items for the survey. Experts on end-of-life care and LTC reviewed various drafts of the questionnaire, which was then pilot-tested on a sample of medical directors and senior administrators working in LTC facilities.

Information was collected on respondents’ demographic and practice characteristics, the importance of potential barriers to providing palliative care, strategies that medical directors would use in providing palliative care, and training respondents had received in palliative care. Open-ended questions also solicited comments in which respondents could identify challenges and suggest ways to improve care of dying residents in ways not listed in the questionnaire.

Procedure

The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care provided a list of licensed LTC facilities. Information included facility address, name of the medical director, number of beds, profit status, and whether the facility belonged to a multifacility organization.

Implementation of the survey included up to 5 mailings. Medical directors were sent a package containing a cover letter, the questionnaire, and a business reply envelope. As some medical directors had responsibilities in more than 1 LTC facility, respondents were asked to complete the survey in reference to the facility to which the questionnaire was addressed.

Analysis

Responses to questions that asked participants to select one response on a 5-point scale (1—not at all important, 2—not very important, 3—neutral, 4—fairly important, 5—very important) were collapsed into 2 meaningful categories. For example, responses to questions on potential barriers to providing palliative care that indicated barriers were “fairly important” or “very important” were coded as “important”; all other responses were coded “not important” by default. For responses rated on the other 5-point scale (1—not at all likely, 2—not very likely, 3—neutral, 4—fairly likely, 5—very likely), which was used for statements about using strategies to improve provision of palliative care, responses indicating “fairly likely” or “very likely” were coded as “likely,” and all other responses were coded “not likely” by default. Descriptive analyses were conducted on all responses.

Principal component analysis was used to identify meaningful groupings of potential barriers to providing palliative care. Because it was possible that certain facility variables could influence the importance of barriers to providing palliative care, the study examined the association of geographic location (urban, rural) and profit status (for profit, non-profit) with potential barriers. The Student t test was used to analyze the relationship of these facility variables to each potential barrier to providing palliative care. The Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, approved the study.

RESULTS

Respondent and practice characteristics

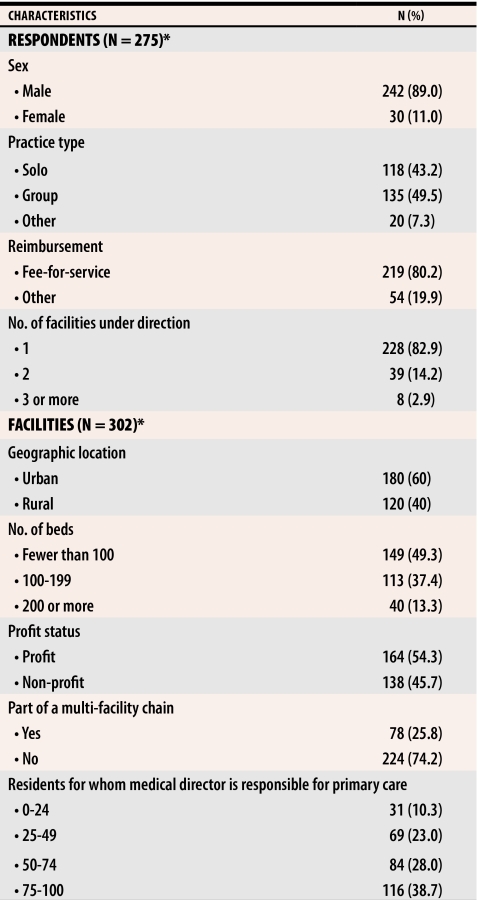

We received completed questionnaires from 275 medical directors (61.1% of all eligible medical directors) representing 302 facilities (56.9% of the LTC facilities in Ontario). Some medical directors were involved in more than 1 facility. Accordingly, we present the characteristics of each respondent (N = 275) and each facility (N = 302) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of medical directors and long-term care facilities

*N varies owing to missing data.

Most medical directors (61.6%) reported that they provided palliative care at least weekly. Relative to other care issues in their facility (eg, behaviour management, respiratory infections) respondents reported that palliative care was either a very (53.6%) or fairly (33.8%) important practice issue.

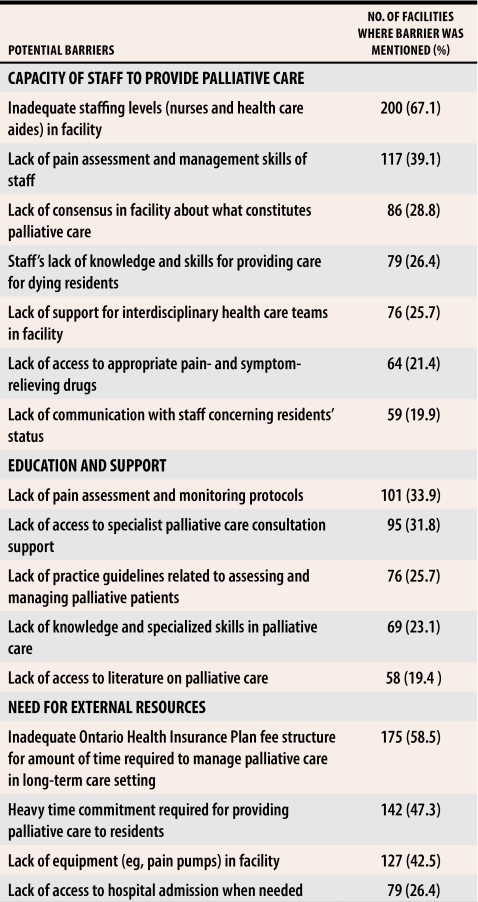

Barriers to providing palliative care

Principal component analysis clustered potential barriers into 3 groups: facility staff’s capacity to provide palliative care, education and support, and the need for external resources. Table 2 shows the barriers associated with each of the 3 groups and the percentage of respondents who reported the barrier as either fairly or very important. Most respondents (67.1%) reported that inadequate staffing in their facilities was a barrier to providing palliative care. This was followed by inadequate financial reimbursement from the Ontario Health Insurance Program to provide palliative care to residents (58.5%), the heavy time commitment required for providing palliative care (47.3%), and the availability of equipment in facilities (42.5%). Student t tests revealed no statistically significant relationship between geographic location or profit status and potential barriers to providing palliative care.

Table 2. Barriers to providing palliative care in long-term care facilities.

N = 302.*

*N varies owing to missing data.

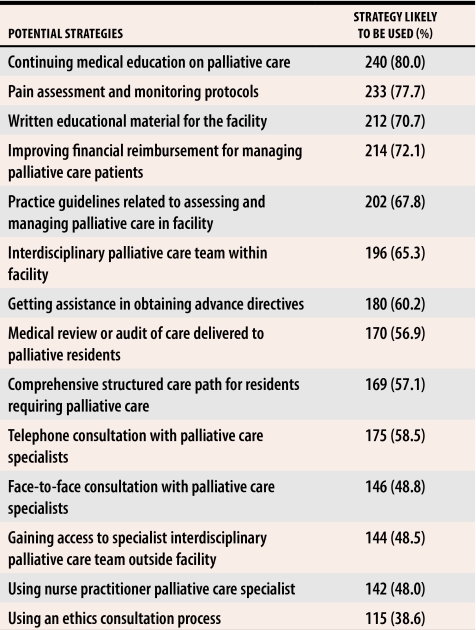

Strategies for providing palliative care

Table 3 shows, in order of medical directors’ preference, potential strategies for improving palliative care. The most highly rated strategy was provision of continuing medical education on palliative care (80.0%). This was followed by the use of pain assessment and monitoring protocols (77.7%), the need to improve financial reimbursement for managing palliative care residents (72.1%), written educational material for the facility (70.7%), and practice guidelines for assessing and managing palliative care in the facility (67.8%).

Table 3. Strategies medical directors would use to improve their provision of palliative care.

N = 302.*

*N varies owing to missing data.

Training for palliative care

Most respondents (90.7%) agreed that their undergraduate medical education did not give them adequate training in palliative care. Most respondents (90.7%) reported that they attended continuing medical education events to develop skills in palliative care. Alternate sources of information on palliative care were reading journal articles and discussions with colleagues. When asked how confident they were in assessing and managing pain in palliative care, only 28.9% (n = 85) reported being very confident, 66.7% (n = 196) reported being fairly confident, 2.7% (n = 8) reported being neutral, and 1.7% (n = 5) reported being not at all confident.

DISCUSSION

In our study, most medical directors reported that palliative care was an important practice issue in their facilities. Currently, residents are admitted into LTC facilities with limited life expectancy where the overall mortality rate is 20% to 25% each year.2 There is also a growing preference among residents to remain in facilities to die rather than be transferred to hospitals. These changes in LTC facilities demand complex management of residents.

Medical directors identified the most important barrier to providing palliative care as inadequate staffing in their facilities. Many clinicians, researchers, and consumer groups consider current standard staffing levels in North American LTC facilities to be inadequate to ensure high-quality care.27-29 Recognizing this concern, a recent Institute of Medicine report recommended that staffing levels be raised and adjusted in accordance with the case mix of residents.27 Many respondents (42.5%) also reported a lack of equipment in the facility as a barrier to provision of palliative care. Further investigation is warranted to identify the type of equipment needed to provide palliative care in LTC facilities.

Survey respondents reported that providing palliative care to dying residents required a heavy time commitment that was not recognized in their remuneration for medical practice. Both the Ontario Medical Association30 and the College of Family Physicians of Canada31 have recognized concerns about family physicians’ remuneration. Adequate reimbursement for medical practice is viewed as having serious implications for recruitment and retention of physicians in family medicine and has been identified as a priority issue for primary care.31

The most highly rated strategies that medical directors reported they would use to improve care of the dying were of an educational nature. While continuing education is considered an important way to improve quality of care in LTC facilities, the effectiveness of continuing education to improve quality is unproven. The authors of a recent systematic review that focused on LTC continuing education programs found very little rigour in evaluation of these programs.32 There is a strong need for well designed studies to evaluate the effectiveness of continuing education for attending physicians to improve end-of-life care in Canadian LTC settings.

Limitations

Medical directors have a different role from other physicians who work in LTC facilities. Thus, generalizing our findings beyond our surveyed group must be done with caution. A potential limitation of the study is a response rate to our survey lower than desired. This said, the findings of this study have identified salient issues that concern medical directors caring for dying residents in LTC facilities.

Conclusion

Medical directors in our study identified palliative care as an important practice issue that represents complex management in an environment with inadequate staff and equipment. The study also highlighted the specialized role of medical directors who identified continuing education as a key strategy for improving their ability to provide palliative care in their facilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank the medical directors who participated in this study. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr Bédard is a Canada Research Chair in Aging and Health.

Biographies

Dr Brazil teaches in the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics and in the Division of Palliative Care in the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University and is Director of the St Joseph’s Health System Research Network in Hamilton, Ont.

Dr Bédard teaches in the Department of Psychology at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont.

Dr Krueger teaches in the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at McMaster University and is a researcher in the St Joseph’s Health System Research Network.

Dr Taniguchi teaches in the Division of Palliative Care in the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University.

Ms Kelley teaches in the Department of Social Work at Lakehead University.

Dr McAiney teaches in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences at McMaster University.

Dr Justice is a researcher in the St Joseph’s Health System Research Network.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Teno JM. Now is the time to embrace nursing homes as a place of care for dying persons. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(2):293–296. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver DP, Porock D, Zweig S. End-of-life care in U. S. nursing homes: a review of the evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:147–155. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123063.79715.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SC, Teno JM, Mor V. Hospice and palliative care in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):717. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.005. 717-34,vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson L, Henderson M. Care of the dying in long-term care settings. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16(2):225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeSilva DL, Dillon JE, Teno JM. The quality of care in the last month of life among Rhode Island nursing home residents. Med Health R I. 2001;84(6):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sengstaken EA, King SA. The problems of pain and its detection among geriatric nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(5):541–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Weitzen S, Wetle T, Mor V. Persistent pain in nursing home residents. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2081. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2081-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ersek M, Kraybill BM, Hansberry J. Investigating the educational needs of licensed nursing staff and certified nursing assistants in nursing homes regarding end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1999;16(4):573–582. doi: 10.1177/104990919901600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson L, Henderson M, Min D, Menon M. As individual as death itself: a focus group study of terminal care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(1):117–125. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis SS, Loving G, McClanahan L, Bernard M. Hospitalization patterns and palliation in the last year of life among residents in long-term care. Gerontologist. pp. 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Maddocks I. Palliative care in the nursing home. Prog Palliat Care. 1996;4(3):77–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson C, Molloy W, Jubelius R, Guyatt GH, Bedard M. Provisional educational needs of health care providers in palliative care in three nursing homes in Ontario. J Palliat Care. 1997;13(3):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Froggatt K. Changing care practices: beyond education and training to ‘practice development. ’ In: Hockley J, Clark D, editors. Facing death: palliative care for older people in care homes. Buckingham, Engl: Open University Press; 2002. pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidell M. The training needs of carers. In: Samson-Katz J, Peace S, editors. End of life in care homes: a palliative care approach. Oxford, Engl: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levenson SA. Long-term care in geriatrics: the long-term care medical director. Clin Fam Pract. 2001;3(3):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willging P. The future of long-term care and the role of the medical director. Clin Geriatr Med. 1995;11(3):531–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimant J. Roles and responsibilities of attending physicians in skilled nursing facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:231–243. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000075915.15039.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bern-Klug M, Buenaver M, Skirchak D, Tunget C. “I get to spend time with my patients”: nursing home physicians discuss their role. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:145–151. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000061473.13422.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levinson MJ, Musher J. Current role of the medical director in community-based nursing facilities. Clin Geriatr Med. 1995;11(3):343–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winn P, Cook JB, Bonnel W. Improving communication among attending physicians, long-term care facilities, residents, and residents’ families. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:114–122. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000113430.64231.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winn P, Dentino AN. Quality palliative care in long-term care settings. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:197–206. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000126425.05045.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario long-term care facility employment information site. Toronto, Ont: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2005. [cited 2005 August 22]. Available at: http://www.ltccareers.com/english/training_nurses.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flacker JM, Won A, Kiely DK, Iloputaife I. Differing perceptions of end-of-life care in long-term care. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(1):9–12. doi: 10.1089/109662101300051889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bern-Klug M, Gessert CE, Crenner CW, Buenaver M, Skirchak D. “Getting everyone on the same page”: nursing home physicians’ perspectives on end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(4):533–534. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dillman D. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. New York, NY: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. Nursing staff in hospitals and nursing homes: is it adequate? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington C, Kovner C, Mezey M, Kayser-Jones J, Burger S, Mohler M, et al. Experts recommend minimum nurse staffing standards for nursing facilities in the United States. Gerontologist. 2000;40(1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of long-term care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ontario Medical Association, Section on General and Family Practice. Family medicine in Ontario: present and future challenges. Ont Med Rev. 2003;70:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.College of Family Physicians of Canada. Family medicine in Canada. Vision for the future. Mississauga, Ont: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2004. [cited 2005 August 22]. Available at: http://www.cfpc.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aylward S, Stolee P, Keat N, Johncox V. Effectiveness of continuing education in long-term care: a literature review. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):259–271. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]