Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To outline how advance care planning is a process of communication among patients, their families, and health care providers regarding appropriate care for patients when they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Level I evidence supports systematic implementation of advance care planning under controlled circumstances, such as in institutions. Level II evidence supports exploring factors that determine treatment preferences and change treatment preferences and other factors that complicate the process of end-of-life decision making. Level III evidence supports the approach to advance care planning in the office described in this article.

MAIN MESSAGE

Family physicians can help prevent the suffering of patients with chronic illnesses by facilitating discussion of end-of-life issues. The approach suggested in this article will help reduce avoidance of the issues and minimize the difficulty of discussing issues crucial to patients and their families.

CONCLUSION

Advance care planning can prevent suffering and enable patients to receive care congruent with their goals at the end of their lives. Family physicians can be key to facilitating this process.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Illustrer le fait que la planification à l’avance des soins est un processus dans lequel patient, famille et personnel soignant s’entendent sur les soins appropriés que le patient devra recevoir lorsqu’il ne sera plus capable d’en décider lui-même.

SOURCE DE L’INFORMATION

Il existe des preuves de niveau I en faveur d’une mise en place systématique d’un processus de planification préalable des soins dans certaines circonstances, comme en milieu institutionnel. Il y a des preuves de niveau II à l’effet qu’on doit rechercher les facteurs qui déterminent et ceux qui modifient les préférences de traitement, de même que les facteurs qui compliquent le processus de prise de décision en fin de vie. Enfin, il y a des preuves de niveau III en faveur de la méthode de planification préalable des soins décrite dans cet article.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Le médecin de famille peut aider à alléger les souffrances des malades chroniques en facilitant la discussion des questions relatives à la phase terminale de la vie. La méthode suggérée dans cet article devrait permettre d’aborder plus facilement la question tout en minimisant la difficulté associée à la discussion d’issues primordiales pour le patient et sa famille.

CONCLUSION

La planification à l’avance des soins peut alléger les souffrances et permettre au patient de recevoir des soins qui respectent ses objectifs à la fin de sa vie. Le médecin de famille peut jouer un rôle clé pour faciliter ce processus.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Raising the issue of advance care with the elderly and patients whose diseases are chronic allows family physicians to better respect their patients’ wishes regarding end-of-life care and avoid potential conflicts or mis-communication with family members.

Introduce the topic in the course of regular care and in the context of wanting to understand patients’ wishes and to address any concerns about their future medical care.

Be prepared to listen and allow patients time to express their values, preferences, and fears. Having a proxy decision maker accompany patients is helpful.

Several scenarios are presented that encourage discussion about key issues, including the expected results of resuscitation. Record the results of your discussion and update the record as the patient’s condition changes.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

En abordant la question de la planification préalable des soins avec les personnes âgées et les malades chroniques, le médecin de famille pourra mieux respecter les volontés du patient au sujet des soins de fin de vie tout en évitant les conflits ou malentendus potentiels avec les membres de la famille.

Aborder ce sujet à l’occasion d’une consultation de routine et avec l’intention de comprendre les volontés du patient et de discuter de ses préoccupations concernant ses soins de santé futurs.

Une écoute patiente permettra au patient d’exprimer ses valeurs, ses préférences et ses craintes. La présence d’un mandataire auprès du patient est souhaitable.

L’article présente plusieurs scénarios susceptibles de faciliter la discussion des questions clés, incluant les résultats potentiels d’une réanimation. Inscrire les résultats de la discussion au dossier et mettre ces notes à jour à mesure que l’état du patient évolue.

Advance care planning is a process of communication among patients, their families, and health care providers regarding the care that will be appropriate for patients when they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves. All patients with chronic life-limiting illnesses (cardiopulmonary disease, renal failure, cancer, degenerative neurologic disease) should be offered the opportunity to prepare advance directives as part of chronic disease management.

A Canadian study1 documenting high-quality end-of-life care from patients’ perspectives noted that avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying and achieving a sense of control were extremely important. To achieve these goals, patients had to be aware of their prognoses.

Case

Mrs Johnston, a 76-year-old woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), has been admitted to hospital several times in the past year. She is short of breath with any amount of activity despite maximal doses of inhaled bronchodilators and steroids and is barely coping with living alone with home support. During the last few days, she has become short of breath at rest and has developed a productive cough. She has been brought into the emergency department in an obtunded state due to impending respiratory failure. Having no guidance from an advance directive and facing a patient in extreme distress, the emergency physician has chosen to intubate and ventilate Mrs Johnston and to proceed with treating her pneumonia and exacerbation of COPD.

Mrs Johnston’s family has arrived from the nearby town and has become very distressed to see her in the intensive care unit. They report that their mother told them she never wanted to have any machines keeping her going and that she felt she was nearing the end of her life. Family members did not realize that Mrs Johnston had never discussed this with her family physician and are angry that the medical staff made this decision.

Physicians sometimes find discussing end-of-life issues difficult owing to lack of training and experience in this area2 and owing to a mistaken belief that patients will not welcome the discussion. A survey of patients with COPD found that less than 1% would find a discussion of advance care directives too disturbing to pursue.3 If the topic is approached from the standpoint of respecting patients’ wishes and choices rather than the standpoint of when treatment should be withdrawn or stopped, patients are much more receptive.

Advance care planning should be revisited both regularly and after major changes in health status because preferences for care tend to change following major changes in health.4 An exception to this is dementing illnesses, as decisions about end-of-life care must be made before patients become cognitively impaired to the point where they can no longer make decisions. As well, all patients without chronic illnesses could be invited to discuss their preferences for care if they were to have catastrophic events that rendered them unable to make decisions. A study5 of the trajectories of dying identified age 80 as the average age of sudden death, so initiating discussion of advance directives after age 70 would be reasonable.

Sources of information

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care indicated that level I evidence exists for systematic implementation of advance care planning under controlled circumstances, such as in institutions. Not surprisingly, no similar evidence exists for advance care planning for people living in the community who have a variety of stages and types of chronic illnesses. There is level II evidence for exploring factors determining treatment preferences, factors influencing changing treatment preferences, and other factors that complicate end-of-life decision making. Level III evidence and clinical experience support the approach to advance care planning in the office described in this article.

Main message

How to set up a visit for advance care planning.

Physicians should suggest the topic of advance care planning when arranging future visits with patients. The topic can be introduced with open-ended questions, such as, “Mr K., if you were unable to make health care decisions for yourself, I would want to be able to respect your wishes. Have you ever written a living will or discussed this with your family? Advance care planning is a routine part of my care of you, and I would like to use our next visit to discuss it.”

Ideally, physicians should then provide patients with information about advance care planning so they can think about it before returning. Information should outline patients’ right to refuse or stop therapy because many patients are unaware of their rights in decision making.6 It is also important that patients realize that their comfort and quality of life is a priority for their physicians even if they refuse or stop treatment. The information physicians provide to patients should be in keeping with the laws of the province or territory where patients reside, as the legislation varies in different provinces and territories.

If possible, surrogate decision makers should attend discussions with patients. The ideal surrogate decision maker knows the patient well enough to represent his or her views on investigation and treatment. This person is not always a family member. Without an identified surrogate decision maker, the family becomes the decision maker by default. Physicians should maintain contact information for surrogate decision makers. Having 2 surrogate decision makers is desirable in case one is unavailable when needed.

How to get the discussion started.

A qualitative study determined that 3 questions could elicit most of the important issues in end-of-life decision making.7 They are:

What present or future experiences are most important for you to live well at this time in your life?

What fears or worries do you have about your illness or medical care?

What sustains you when you face serious challenges in life?

Using these questions in language patients can understand will help elicit patients’ values and beliefs and identify goals that could affect decision making (eg, the desire to live until a certain event occurs). Be prepared to listen. Most people can articulate thoughts or concerns to a physician in less than 60 seconds.8 Facilitating comments, such as “mmh,” “go on,” or “I see,” can help continue the flow of information from patients. Repeating patients’ last statement tends to encourage them to elaborate further on that issue and might inhibit the flow of further valuable information.

Ask about previous experience with serious illness in family or friends, as it will give you insight into how patients might view their own illnesses and how they might wish to be treated at the end of life. Experiences viewed very negatively could illustrate scenarios that researchers have termed “worse than death.”9 Finding out what aspect of the experience was disturbing could help you understand what patients value in their lives.

Aids to decision making.

Patients can rarely state their preferences for care without guidance, so it is appropriate to use scenarios to help them express preferences. A qualitative study of elderly people with advanced disease revealed 3 major influences on treatment preferences: treatment burden, treatment outcome, and the likelihood of the outcome.10

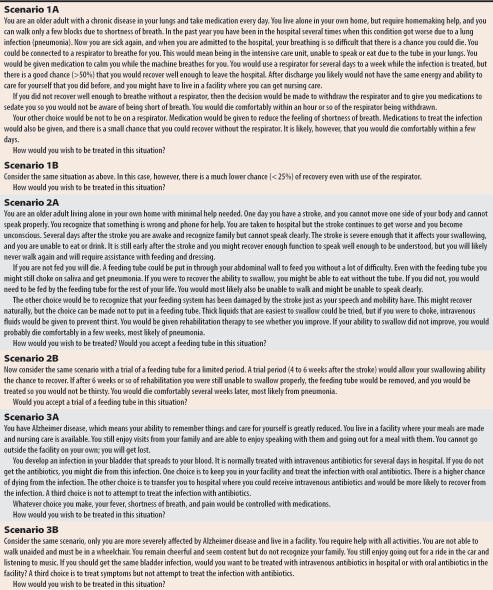

A study of 56 advance care planning interviews11 noted that physicians tended to present either hopeless situations in which no one would want treatment or situations resulting in restoration of health where everyone would want treatment. Table 1 gives examples of scenarios in which there is some degree of uncertainty and in which none of the patients return to their previous state of health. Each scenario is looked at twice; only the prognosis for outcome changes. In each scenario, active treatment of symptoms continues until death.

Table 1.

Hypothetical scenarios for advance care planning

By using these scenarios, physicians could get a sense of the issues that are critical for their patients. Physicians should reflect their understanding back to patients to see whether patients agree with the statements. For example, if a patient refuses intervention when the outcome is disability and dependence, a physician could say, “You seem to be telling me that independence is more important than length of life.” It is important to clarify what people mean when they say such things as, “I don’t want to be a vegetable” or “I don’t want to be a burden.” Asking them to elaborate on what a vegetable or burden is to them will give physicians better overall information on values when the time comes to make decisions.

These scenarios will not be helpful for people who already live with extensive disability. In fact, such people might not consider themselves disabled at all. It is important to focus on what patients would consider a disability and what would be worse than death to them.

Because many believe that resuscitation is often successful,12 resuscitation should always be discussed. A way of raising this issue is to state, “All will be done to help you live as well as possible for as long as possible, but when your disease becomes very serious and you die of the illness, we will not try to resuscitate you. Resuscitation would have almost zero chance of success and would only return you to the state you were in just before death.” Focusing on what will be done for patients clears up the common misperception that “do not resuscitate” means “do not treat.” Patients should understand also that they can still choose to receive disease-modifying therapy but that they will not be resuscitated when they die of the illness.

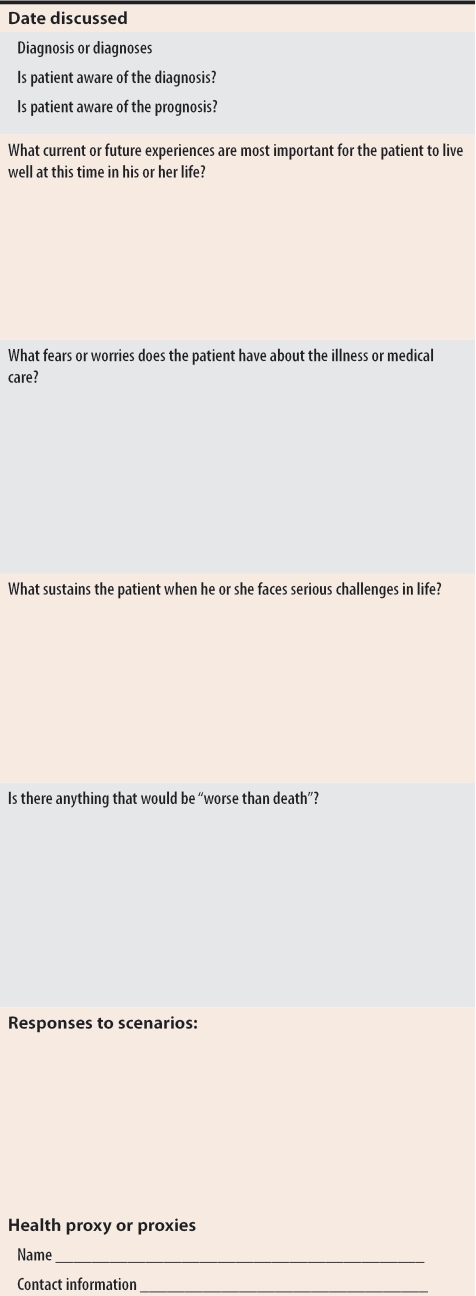

Documenting the visit and decisions.

Over the years, what kind of instructions should be written to help guide care has been debated. The language needs to be specific enough to be useful for physicians writing orders yet not so directive it hampers provision of best care to patients in specific medical situations. It would be helpful to record patients’ answers to the 3 questions about what gives their lives quality, their current goals, “decisions” about scenarios, and any further comments they have on issues, such as what is worse than death. Figure 1 lists details that could be recorded at advance care planning visits.

Figure 1.

Advance care planning documentation

Physicians should also encourage patients to complete advance directives that are legal in their provinces or territories and to share copies with their proxies, families, and legal and spiritual advisors so as many people as possible are informed about their preferences for care. Advance directives should accompany patients and be presented at any visit to hospital or to new health care providers.

Case wrap-up

In the case of Mrs Johnston, the family elected to continue treatment because she was already intubated and ventilated and showed some signs of improvement. But after 5 days’ therapy, she showed no signs of being able to be weaned from the ventilator. A family meeting was held in which she and her family decided to discontinue ventilation. She died peacefully less than an hour after extubation. The staff at the bedside reported that the family were angry and conflicted throughout the ordeal. The staff said it was difficult to provide care for a patient who did not wish to receive that kind of care and wondered whether other patients’ care had been compromised because the intensive care unit was full.

Conclusion

Family physicians can become skilled at helping patients to state preferences for care at the end of life.

Physicians should plan to spend a visit discussing advance care planning as part of managing chronic diseases.

Using scenarios with various outcomes can help clarify patients’ values and goals for end-of-life care.

Physicians should always raise the issue of resuscitation but should focus on what will be done to promote quality and length of life rather than making “do not resuscitate” sound like “do not treat.”

All information should be recorded, and patients should be urged to complete legal advance directives and share them widely.

Advance directives should accompany patients and be presented during hospital admission and when patients meet new health care providers.

Essentials of decision making in health care.

Always try to ask patients first. Presume they are competent to make decisions until proven otherwise. Patients might not have the capacity to make decisions, but might still be able to express preferences and be involved to some degree in decision making (eg, they might be able to say whether they would rather remain in a facility or go to hospital).

If patients are unable to make decisions due to illness or loss of capacity from dementia, inquire about advance directives and about substitute decision makers.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded from the National Envelope of Health Canada’s Primary Health Care Transition Fund. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the official policies of Health Canada.

Biography

Dr Gallagher is Head of the Division of Residential Care for Providence Health, is Clinical Professor in the Division of Palliative Care at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC, and is Co-Chair of Public Information and Awareness for the National Strategy on Palliative and End-of-Life Care.

References

- 1.Singer P, Martin D, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281(2):163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langerman A, Angelos P, Johnston C. Opinions and use of advance directives by physicians at a tertiary care hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2000;8(3):14–18. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200008030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heffner JE. End-of-life ethical issues. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1998;4(3):541–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditto D, Smucker W, Danks J, Jacobson JA, Houts RM, Fagerlin A, et al. Stability of older adults’ preferences for life-sustaining medical treatment. Health Psychol. 2003;22(6):605–615. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunney J, Lynn J, Foley D, Lipson S, Guralnik J. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira MJ, DiPiero A, Gerrity MS, Feudtner C. Patients’ knowledge of options at the end of life: ignorance in the face of death. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2483–2488. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz C, Lennes I, Hammes B, Lapham C, Bottner W, Yunsheng M. Honing an advance care planning intervention using qualitative analysis: the living well interview. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(4):593–603. doi: 10.1089/109662103768253704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckman H, Frankel R. The effect of physician behaviour on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692–696. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-5-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick D, Pearlman R, Starks H, Cain KC, Cole WG, Uhlmann RF. Validation of preferences for life-sustaining treatment: implications for advance care planning. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:509–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-7-199710010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried T, Bradley E. What matters to seriously ill older persons making end-of-life treatment decisions? A qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(2):237–244. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tulsky J, Fischer G, Rose M, Arnold R. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:441–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones GK, Brewer K, Garrison H. Public expectations of survival following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(1):48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]