Abstract

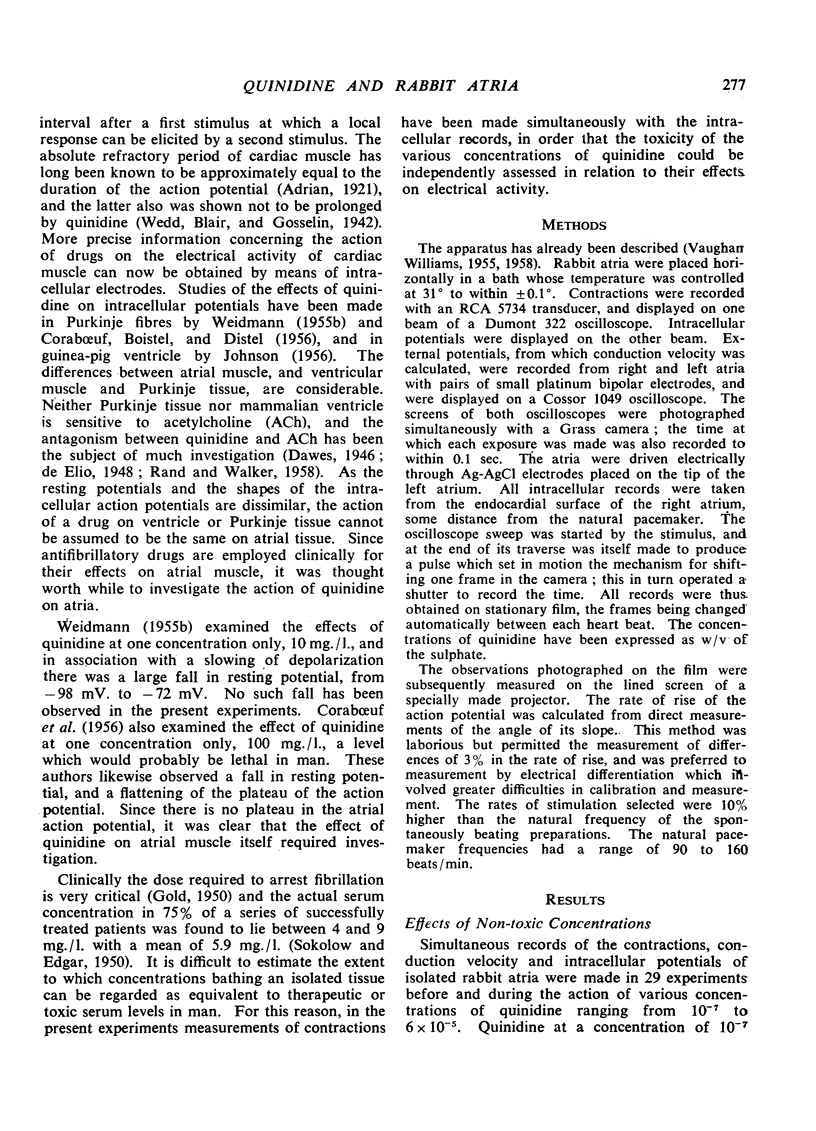

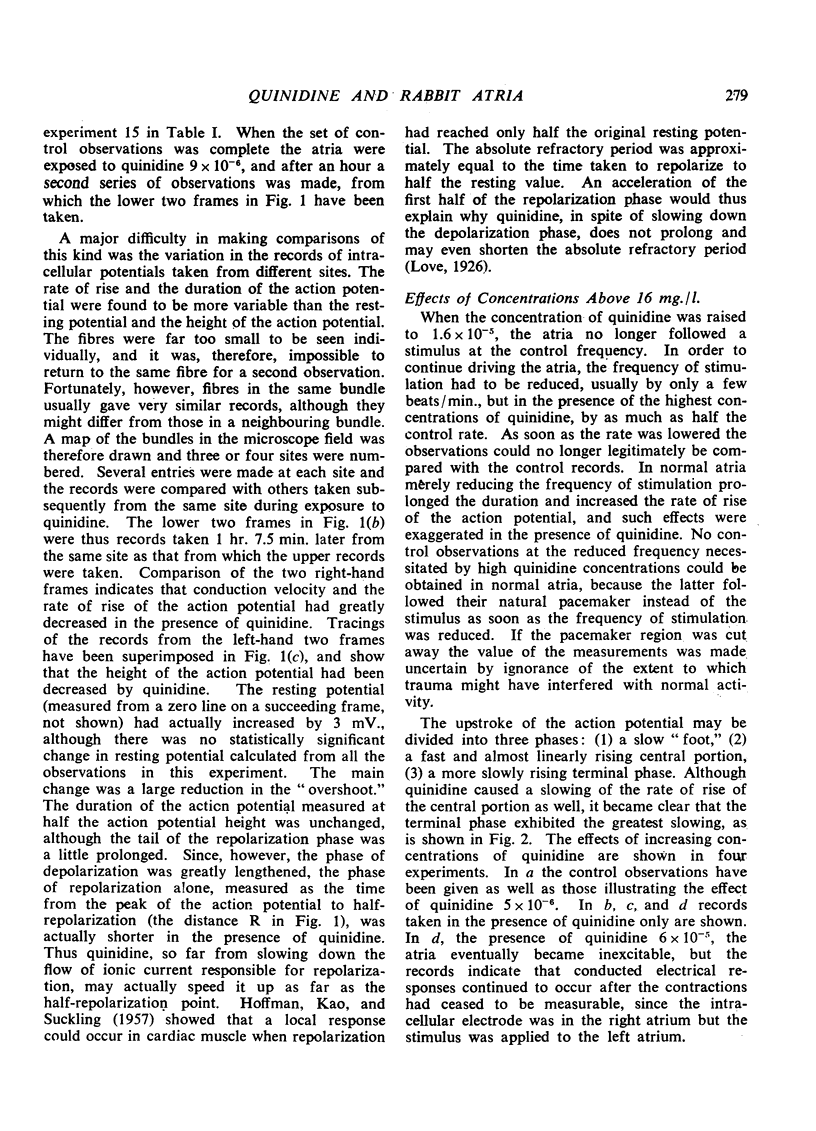

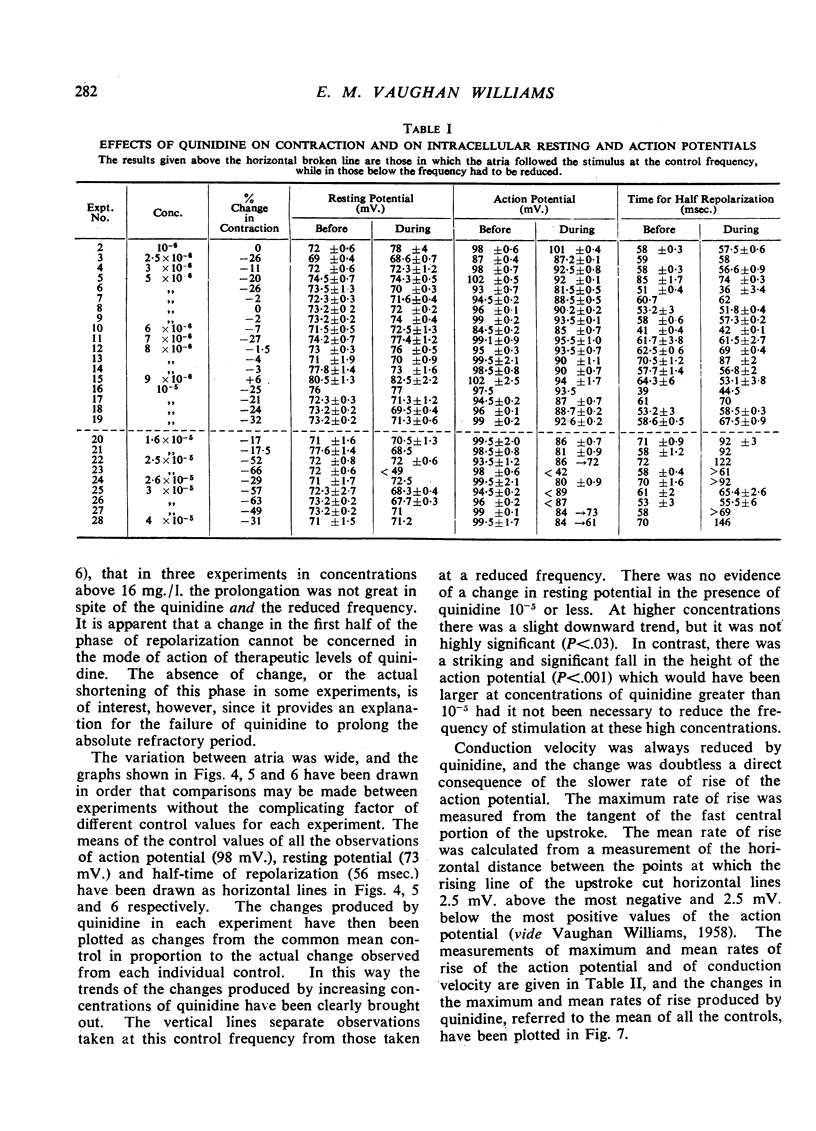

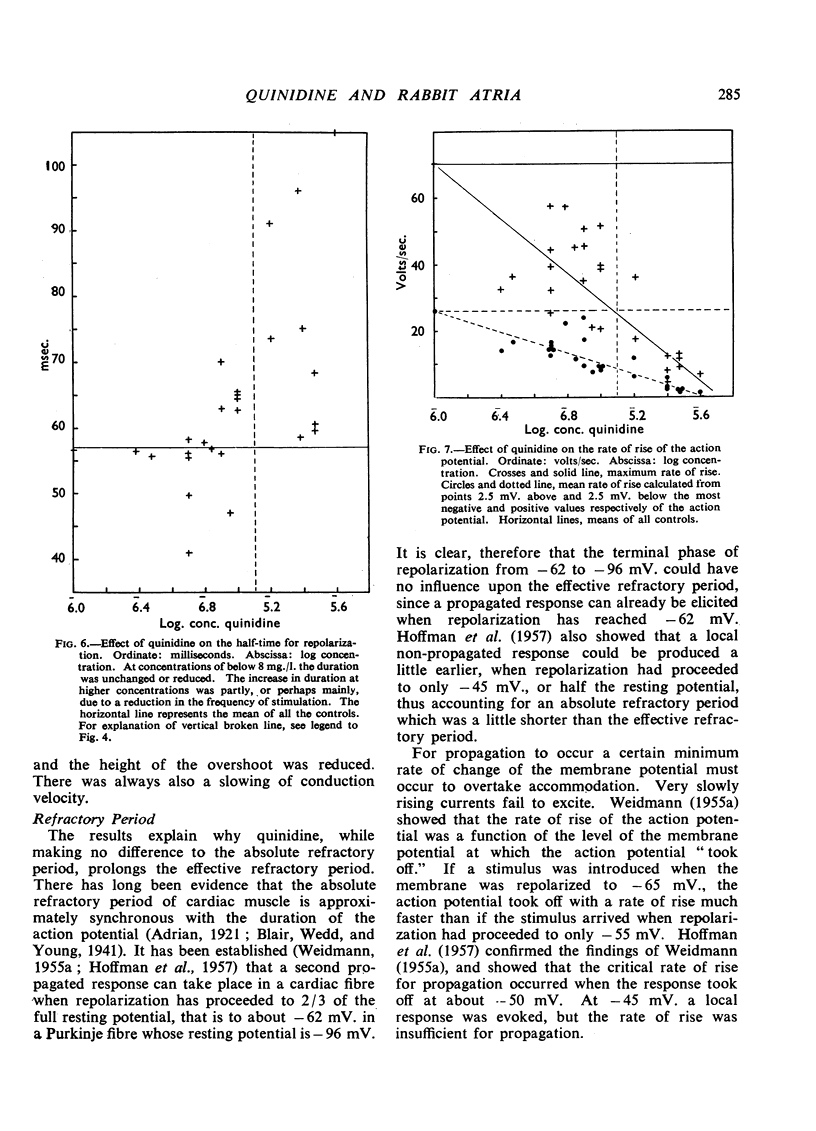

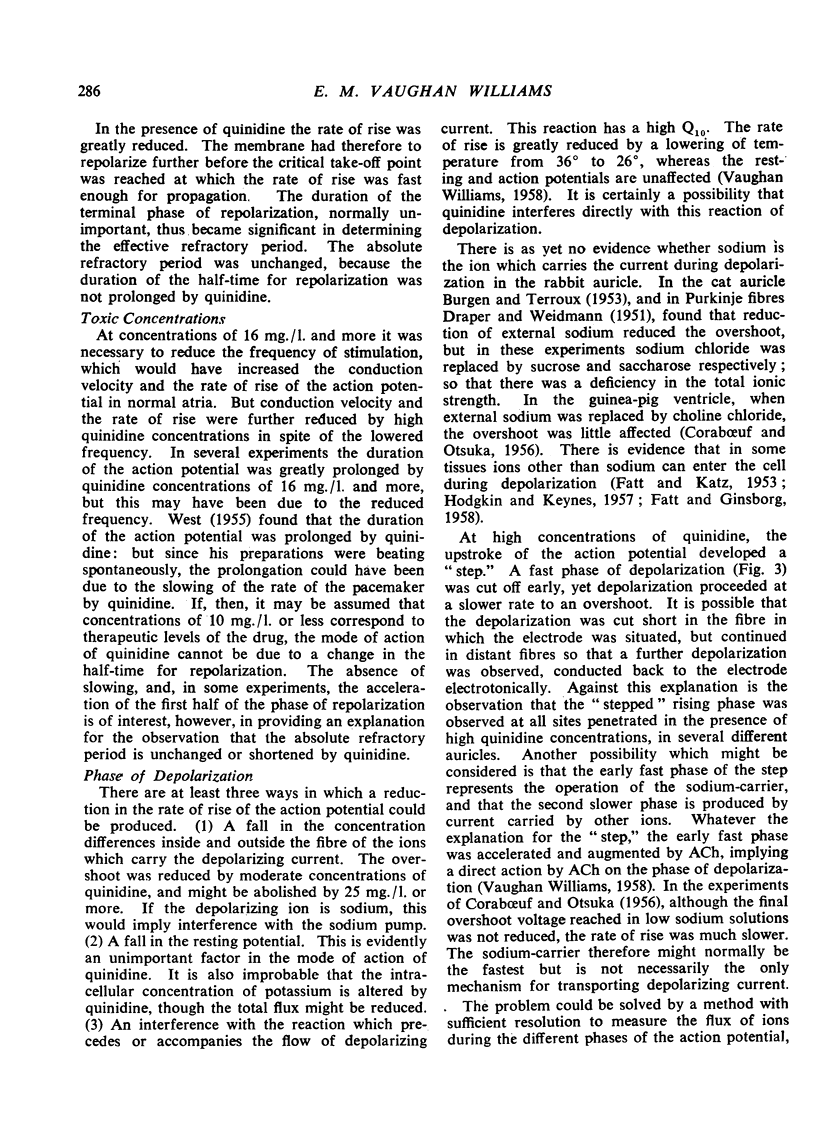

An attempt has been made to show why quinidine, which has long been known not to lengthen the duration of the cardiac action potential, measured with external electrodes, and also not to lengthen, and sometimes to shorten, the absolute refractory period, nevertheless reduces the maximum frequency at which atria can respond to a stimulus. Simultaneous measurements have been made in electrically driven isolated rabbit atria of contractions, conduction velocity and intracellular potentials before and during exposure to a wide range of concentrations of quinidine sulphate. The resting potential remained undiminished, in contrast to the effect of quinidine on Purkinje fibres. In the therapeutic range of doses, up to 10 mg./l., the half-time for repolarization was either shortened or unchanged, thus providing an explanation for the failure of quinidine to prolong the absolute refractory period. In contrast, even at low concentrations of quinidine, conduction velocity and the rate of rise of the action potential were greatly slowed, and the height of the overshoot was reduced. The terminal phase of the action potential was prolonged. It is known that the rate of rise of the action potential is a function of the level of repolarization at which an impulse takes off (the more negative the take-off point, the faster the rate of rise). Normally, a stimulus introduced when repolarization has proceeded to 2/3 of the resting potential evokes a response with a rate of rise fast enough for propagation, so that the duration of the terminal 1/3 of the phase of repolarization has no influence upon the length of the effective refractory period. In the presence of quinidine, however, the rate of rise itself was directly reduced, thus repolarization had to proceed further before the critical take-off point was reached at which the rate of rise was fast enough for propagation, and the duration of the terminal phase of repolarization thus became significant. It has been concluded that quinidine prolongs the effective refractory period by slowing the phase of depolarization, without any change necessarily occurring in the half-time for repolarization, which determines the absolute refractory period. Acetylcholine accelerated the rate of rise of the action potential even in the presence of high concentrations of quinidine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ARMITAGE A. K., BURN J. H., GUNNING A. J. Ventricular fibrillation and ion transport. Circ Res. 1957 Jan;5(1):98–104. doi: 10.1161/01.res.5.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian E. D. The recovery process of excitable tissues: Part II. J Physiol. 1921 Aug 3;55(3-4):193–225. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1921.sp001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRISCOE S., BURN J. H. Quinidine and anticholinesterases on rabbit auricles. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1954 Mar;9(1):42–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1954.tb00814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURGEN A. S. V., TERROUX K. G. The membrane resting and action potentials of the cat auricle. J Physiol. 1953 Feb 27;119(2-3):139–152. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURN J. H., GUNNING A. J., WALKER J. M. The effect of KCl on atrial fibrillation caused by acetylcholine. Circ Res. 1956 May;4(3):288–292. doi: 10.1161/01.res.4.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARMELIET E., LACQUET L. L'influence de la température et des ions potassium et sodium sur la duree du potentiel d'action cardiaque en fonction de la fréquence. Arch Int Physiol Biochim. 1956 Jun;64(3):513–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORABOEUF E., BOISTEL J., DISTEL R. L'action de la quinidine sur l'activité électrique élémentaire du tissu conducteur du coeur de chien. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1956 Feb 27;242(9):1225–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORABOEUF E., OTSUKA M. L'action des solutions hyposodiques sur les potentiels cellulaires de tissu cardiaque de mammifères. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1956 Jul 23;243(4):441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWES G. S., VANE J. R. The refractory period of atria isolated from mammalian hearts. J Physiol. 1956 Jun 28;132(3):611–629. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIPALMA J. R., SCHULTZ J. E. Antifibrillatory drugs. Medicine (Baltimore) 1950 May;29(2):123–168. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAPER M. H., WEIDMANN S. Cardiac resting and action potentials recorded with an intracellular electrode. J Physiol. 1951 Sep;115(1):74–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATT P., GINSBORG B. L. The production of regenerative responses in crayfish muscle fibres by the action of calcium, strontium and barium. J Physiol. 1958 Feb 17;140(2):59–60P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HODGKIN A. L., KEYNES R. D. Movements of labelled calcium in squid giant axons. J Physiol. 1957 Sep 30;138(2):253–281. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B. F., KAO C. Y., SUCKLING E. E. Refractoriness in cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol. 1957 Sep;190(3):473–482. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.190.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B. F., SUCKLING E. E. Effect of heart rate on cardiac membrane potentials and the unipolar electrogram. Am J Physiol. 1954 Oct;179(1):123–130. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.179.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLAND W. C. A possible mechanism of action of quinidine. Am J Physiol. 1957 Sep;190(3):492–494. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.190.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL J. M. Effects of low temperatures on transmembrane potentials of single fibers of the rabbit atrium. Circ Res. 1957 Nov;5(6):664–669. doi: 10.1161/01.res.5.6.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL J. M., VAUGHAN WILLIAMS E. M. Pacemaker potentials: the excitation of isolated rabbit auricles by acetylcholine at low temperatures. J Physiol. 1956 Jan 27;131(1):186–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAND M. J., WALKER J. M. A comparison of antifibrillatory drugs in the heart-lung preparation. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1958 Mar;13(1):107–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1958.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUTWEIN W., GOTTSTEIN U., FEDERSCHMIDT K. Der Einfluss der Temperatur auf den Aktionsstrom des excidierten Purkinje-Fadens, gemessen mit einer intracellulären Elektrode. Pflugers Arch. 1953;258(3):243–260. doi: 10.1007/BF00363463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIDMANN S. The effect of the cardiac membrane potential on the rapid availability of the sodium-carrying system. J Physiol. 1955 Jan 28;127(1):213–224. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]