Abstract

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi were labeled by green fluorescent protein chimeras and observed by time-lapse confocal microscopy during the rapid cell cycles of sea urchin embryos. The ER undergoes a cyclical microtubule-dependent accumulation at the mitotic poles and by photobleaching experiments remains continuous through the cell cycle. Finger-like indentations of the nuclear envelope near the mitotic poles appear 2–3 min before the permeability barrier of the nuclear envelope begins to change. This permeability change in turn is ∼30 s before nuclear envelope breakdown. During interphase, there are many scattered, disconnected Golgi stacks throughout the cytoplasm, which appear as 1- to 2-μm fluorescent spots. The number of Golgi spots begins to decline soon after nuclear envelope breakdown, reaches a minimum soon after cytokinesis, and then rapidly increases. At higher magnification, smaller spots are seen, along with increased fluorescence in the ER. Quantitative measurements, along with nocodazole and photobleaching experiments, are consistent with a redistribution of some of the Golgi to the ER during mitosis. The scattered Golgi coalesce into a single large aggregate during the interphase after the ninth embryonic cleavage; this is likely to be preparatory for secretion of the hatching enzyme during the following cleavage cycle.

INTRODUCTION

What happens to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi during mitosis is of interest on several grounds. By characterizing membrane dynamics in mitosis, it may be possible to learn more about the nature of the membrane budding, transport, and fusion processes that occur between the ER and Golgi (Lowe et al., 1998). The two organelles may also have specific mechanisms for partitioning them into daughter cells (Warren and Wickner, 1996) and may be involved in regulating physiological processes during cell division.

It is commonly thought that the ER and Golgi are changed drastically during mitosis. In textbooks, it is stated that the ER becomes vesiculated during mitosis (Murray and Hunt, 1993, p. 70; Alberts et al., 1994, p. 918; Lodish et al., 1995, p. 1213). A variant of this view is that fragmentation is minimal in cultured cells, whereas the ER of cells in tissues undergoes breakdown (Warren, 1993). However, there are actually only a few cells in which ER vesiculation in mitosis has been reported (see DISCUSSION).

In contrast to the situation with the ER, there is abundant evidence for changes in the Golgi during mitosis. Dissolution of Golgi stacks has been seen by electron microscopy (Zeligs and Wollman, 1979; Misteli and Warren, 1995), and changes at the light microscopic level have been seen by immunofluorescence (Burke et al., 1982; Hiller and Weber, 1982) and by green fluorescent protein (GFP) imaging in living cells (Shima et al., 1997, 1998). In one case, during the rapid early divisions in the Drosophila embryo, no change seems to occur (Stanley et al., 1997).

The nature of the change in the Golgi is not clear at this time. Evidence from cell fractions supports the conversion to vesicles (Jesch and Linstedt, 1998), whereas other evidence supports small clusters (Shima et al., 1997, 1998). Cell-free systems have been developed, which show vesiculation upon addition of mitotic extracts or activated cell cycle proteins (Warren et al., 1995; Acharya et al., 1998). There is also evidence from oligosaccharide processing against mixing of the Golgi with the ER (Farmaki et al., 1999). A dominant negative mutant of sar1, which blocks ER-to-Golgi transport (Aridor et al., 1995), was reported to have no effect on the Golgi during mitosis or on Golgi redistribution in nocodazole (Shima et al., 1998), but Storrie et al. (1998) used the same mutant to document redistribution of Golgi into ER in untreated cells and a block of redistribution of Golgi in nocodazole. Based on immunocytochemical studies, Thyberg and Moskalewski (1992) have proposed instead that the Golgi is resorbed into the ER during mitosis.

To begin to address these issues, GFP chimeras were expressed in sea urchin embryos. Sea urchin embryos have several characteristics that make them well suited for observations of structural changes during the cell cycle. After about the fifth cleavage, the blastomeres (daughter cells of the fertilized egg) become organized in a single layer around the blastocoel, the large acellular cavity of the blastula. The subsequent divisions occur with the two mitotic poles in the plane of the cellular layer, which is a convenient orientation for light microscopy. Also, as the blastomeres cleave, they become progressively smaller and more easily viewed by high-resolution oil immersion optics. By the time of hatching, the cells have acquired characteristics of a ciliated epithelium. The cells secrete a hatching enzyme (HE) that dissolves the fertilization envelope after the 10th division (LePage and Gache, 1990; Roe and Lennarz, 1990), allowing the embryo to swim away using its newly developed cilia (Masuda, 1979).

In this study, image sequences of the ER and Golgi through the cell cycle were obtained without noticeable photodynamic damage. The image sequences were obtained without using inhibitors to produce synchronized cell populations or inducers of GFP chimera expression. Additionally, a change in the Golgi was observed during a major developmental transition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Obtaining and Injecting Sea Urchin Eggs

Lytechinus variegatus were obtained from Tracy Andacht (Beaufort Marine Station, Beaufort, NC) or from Sue Decker (Davie, FL). The embryo of this species L. variegatus is particularly well suited for observing structural changes during the cell cycle because of its exceptional optical clarity. The egg is ∼105 μm in diameter and is relatively easy to microinject. Furthermore, the embryo develops normally at room temperature, with cell cycle times as brief as 30 min at 24°C. Gametes were obtained from single gonads by injection of a small amount of 0.5 M KCl as described by Fuseler (1973). For injections and observations, eggs were kept in chambers described by Kiehart (1982). Quantitative injection was done using mercury pipettes as described by Hiramoto (1962). Details of methods and equipment for injection are available at http://egg.uchc.edu/injection.

GFP Chimeras

The constructs GFP-KDEL (Terasaki et al., 1996) and KDELRm-GFP (Cole et al., 1996b) have been described previously. Galtransferase-GFP (Galtase-GFP) has also been described previously (Cole et al., 1996b), but mRNA made from the original DNA construct did not become translated in sea urchin eggs. Successful expression was obtained by altering the five nucleotides preceding the start codon (the “Kozak sequence”) to a sequence found in ER calcistorin/protein disulfide isomerase (ECast/PDI), a native sea urchin protein (Lucero et al., 1994). The alteration was accomplished by PCR using the 5′ primer 5′-ggg gga att ctt aaa aat gag gct tcg gga gcc gct cc-3′.

mRNA was transcribed in vitro using a kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The final product was dissolved in water and stored at −70°C (stock concentrations between 0.3 and 1.0 mg/ml). Injections were typically 2% of the cell volume. Eggs were injected and then allowed to recover for >10 min before adding sperm to fertilize them. The embryos were observed at the 16-cell stage to determine the animal vegetal axis of each embryo (the micromeres are present at the vegetal pole). All observations reported here are of the animal half blastomeres using embryos in which the micromeres were situated farthest away from the coverslip. Hatching occurred at approximately the same time as embryos grown outside the chambers.

Reagents

All fluorescent reagents were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). For some experiments, the ER was labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI [DiIC18(3)]) by injecting DiI-saturated oil (Wesson soy bean oil; Hunt-Wesson, Fullerton, CA) into eggs before fertilization (Terasaki and Jaffe, 1991). Nocodazole was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and was kept as a 1 mg/ml stock in DMSO at −20°C.

Light Microscopy and Quantification

Except as indicated, imaging was done with a laser scanning confocal microscope (MRC 600; Bio-Rad, Cambridge, MA) on an upright microscope (Axioskop; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a krypton argon laser. Unless otherwise noted, a Zeiss plan-apo 63× numerical aperture (NA) 1.4 objective lens was used.

The Bio-Rad SOM software was used for making macros to bleach and record images for the fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) experiments (see Figures 3 and 10). A special trigger circuit (http://www2.uchc.edu/∼terasaki/trigger.html) was used to automatically record the confocal images on an optical memory disk recorder (TQ 3038F; Panasonic, Secaucus, NJ). The laser intensity at the back focal plane of the objective was measured by a laser power meter (1815-C; Newport/Klinger, Irvine, CA). Imaging was done with a 10% neutral density filter and with the laser at the low setting; the laser intensity was measured to be ∼40 μW. Photobleaching was done with no neutral density filter and with the laser at the normal setting; the laser intensity was measured to be ∼2 mW. Because the zoom was five to six times greater, the intensity of the photobleaching light was ∼50 × 25 = ∼1250 times the intensity of excitation light used for imaging.

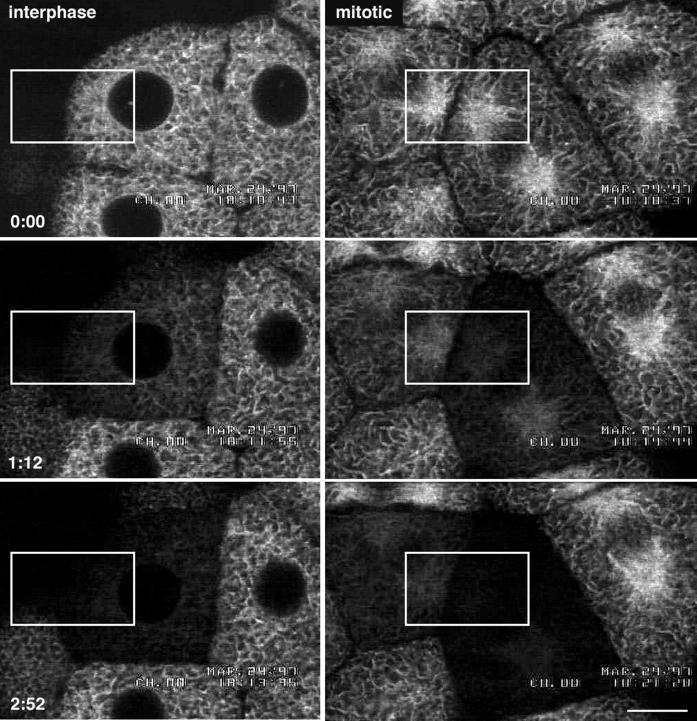

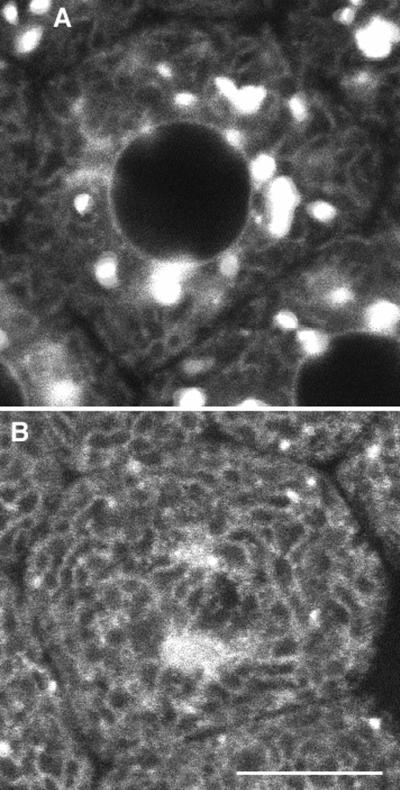

Figure 3.

Evidence that the ER is continuous during mitosis. Blastomeres expressing GFP-KDEL in interphase or metaphase were repetitively bleached using a FLIP protocol. The top panels show the blastomeres before bleaching. The cells were subjected to nine bleach cycles. The confocal microscope was set at 3.1 s per scan. Each cycle consisted of three bleaching scans at high zoom with high laser intensity, followed by one imaging scan at low zoom with low laser intensity, followed by a 10-s wait period. The duration of each cycle was ∼20 s. The total elapsed time for the nine cycles was 2 min 51 s. The middle panels were taken after the fourth bleach (1 min 12 s), and the bottom panels were taken after the ninth bleach (2 min 51 s). The rectangles show the regions that were bleached. Because fluorescence throughout the cell was bleached by this protocol, it is likely that the GFP KDEL is present in a continuous compartment throughout the cell. Bar, 10 μm.

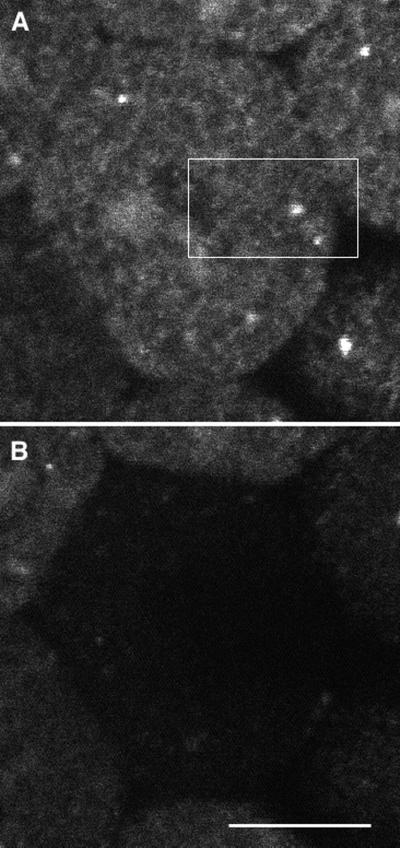

Figure 10.

The fluorescence from Galtase-GFP in a nocodazole-treated (1 μM) treated blastomere was bleached using a FLIP protocol. The image quality is poorer than that shown in Figure 8, because lower illumination levels were used to minimize bleaching. Photobleaching using a FLIP protocol was begun 52 min after nocodazole was added. The protocol was essentially the same as used in Figure 3, except that the wait period was 20 s instead of 10 s, and the relative zoom of bleached to imaged was 6 instead of 5. The duration of each cycle was 30 s, and the total elapsed time for the 10 cycles was 5 min. Fluorescence was diminished throughout the cell, providing strong evidence that Galtase-GFP is in the ER. The size of the field imaged was 59 × 39 μm, and the bleached area was 12 × 7 μm and is indicated by the rectangle. Bar, 10 μm.

For the ER and nuclear envelope permeability experiment (see Figure 4), the confocal microscope was set up with the double labeling filter set (“K1” and “K2”). Alternate images of the Fl 70-kDa dextran and DiI were obtained by manually switching the excitation filters.

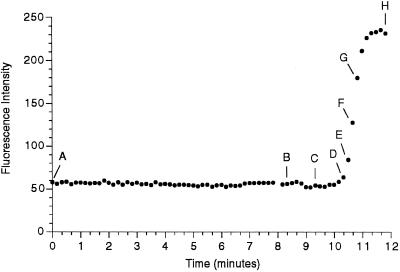

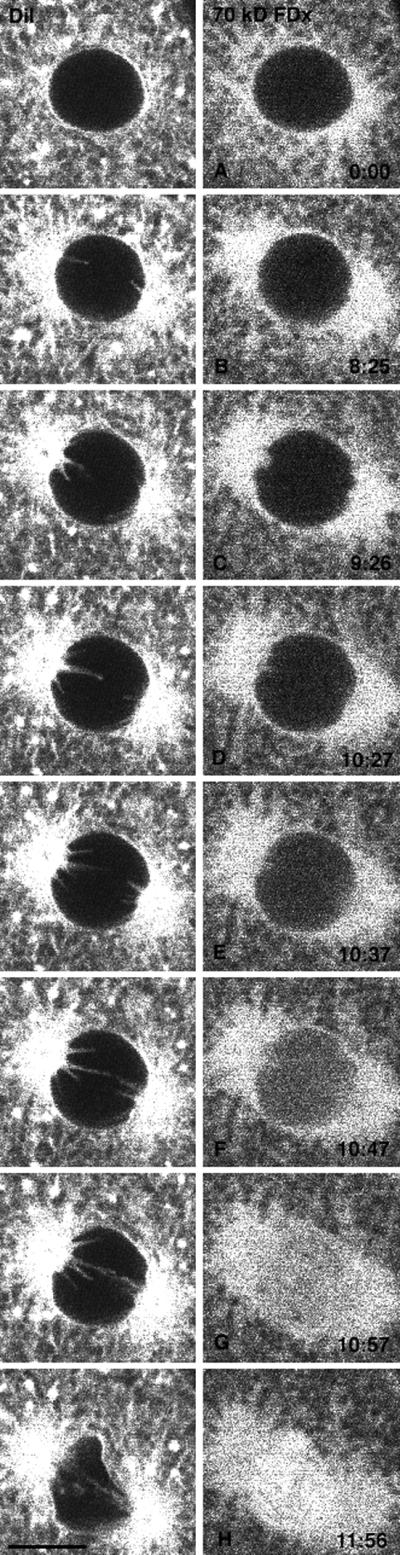

Figure 4.

Evidence that the nuclear envelope projections occur before changes in the nuclear envelope permeability barrier. An egg was injected with both a DiI-saturated oil drop to label the ER and with FDx to monitor nuclear envelope permeability. DiI-labeled, finger-like membrane projections protude into the nucleus before NEBD. DiI and 70-kDa FDx were imaged alternately, every 5 s. The DiI images were taken 5 s previous to the 70-kDa FDx image on the same row. The time in seconds from the beginning of the 70-kDa FDx sequence is indicated. The graph shows the average fluorescence intensity measured in a rectangle of 6.6 × 8.4 μm centered in the nuclear region. Letters on the graph indicate which panel of the figure corresponds to data points on the graph. The 70-kDa FDx begins to enter the nucleus in D, whereas the projections are present ∼2 min earlier in B. Bar, 10 μm.

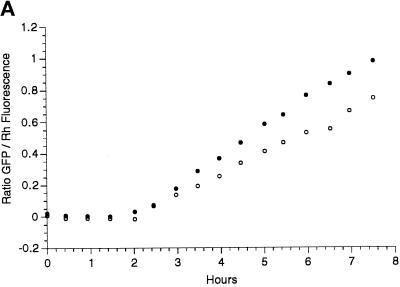

To quantitate the time course of the increase in GFP fluorescence (see Figure 5A), ratio images were formed using rhodamine-dextran; ratio images were used because small changes in focus level can cause changes in fluorescence intensity. Eggs were injected with a 1:1 mixture of 70-kDa Rh dextran and Galtase-GFP mRNA in a volume corresponding to 4% of the egg volume. The final concentration of the Rh dextran was ∼20 μg/ml, and the final concentration of mRNA was the same as in the other experiments. Embryos were imaged with a 10× objective lens (Zeiss, 0.3 NA plan-neofluar) with the confocal aperture completely open. After subtracting off background, a ratio was formed between the GFP and Rh average fluorescence intensities in a rectangle in the middle of the embryo. Data from two embryos are graphed in Figure 5A, and the following linear equations were used for calculating percent increase attributable to synthesis: (0.186 × t) − 0.38 and (0.134 × t) − 0.28, where t is in hours (sixth interphase, t = 4 h; seventh cleavage, t = 4.25 h; and seventh interphase, t = 4.5 h).

Figure 5.

Labeling of Golgi by GFP chimeras. (A) To monitor the time course of GFP increase, eggs were injected with a mixture of mRNA coding for Galtase-GFP and Rh dextran and then fertilized. A ratio was formed of the GFP to Rh fluorescence. Images were taken with a 10× lens with the confocal aperture open to collect as much of the total fluorescence as possible. There was a lag of 2 h followed by a linear increase in fluorescence. Closed and open circles represent two different embryos in the same experiment. (B) An egg was injected with mRNA coding for KDELRm-GFP and then fertilized and imaged after fluorescence had developed. Confocal optical section of a blastomere at the 64-cell stage (between the sixth and seventh cleavages) shows fluorescent spots of varying sizes distributed throughout the cytoplasm. (C) Stereo pair made from a z series sequence containing the section on the left (39 steps with an interval of 0.54 μm). Bar, 10 μm.

For imaging KDELRm-GFP during mitosis at lower magnification (see Figures 6 and 12), the 63× lens was used. The laser was used on the low setting with a 3% neutral density filter, normal scan, and zoom 1. With these settings, the fluorescence from the Golgi was not saturated, and the cytoplasmic fluorescence was dim. For the experiments done at higher magnification (see Figures 8–11), the same lens and laser setting were used with a 10% neutral density filter. The scan setting was slow scan enhance, which results in a three times longer integration time per pixel than normal scan. Because the excitation intensity is three times greater as a result of the neutral density filter used, the resulting image is approximately nine times brighter than those in Figure 6. To obtain higher-resolution details of this brighter image, the zoom was set at 3 with a two-frame average. The images were saved without any postprocessing on the computer hard disk. For quantitation of fluorescence in interphase versus mitosis (see Figures 8 and 9), the original image data were analyzed with the public domain NIH Image program (available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). The original images (i.e., without any changes to the pixel intensity values as they were originally collected), as well as regions chosen for the quantitation, can be viewed or downloaded at http://terasaki.uchc.edu/mitosis.

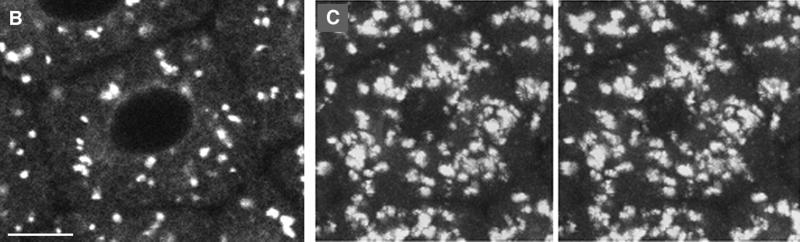

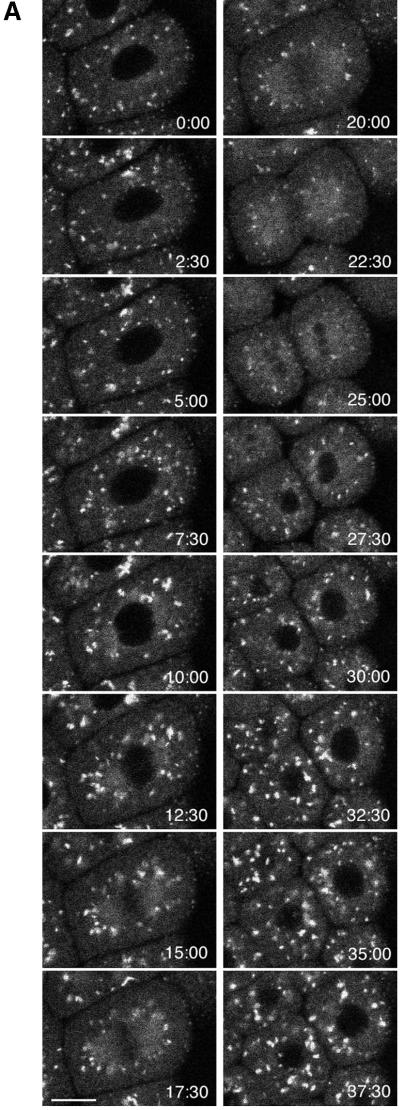

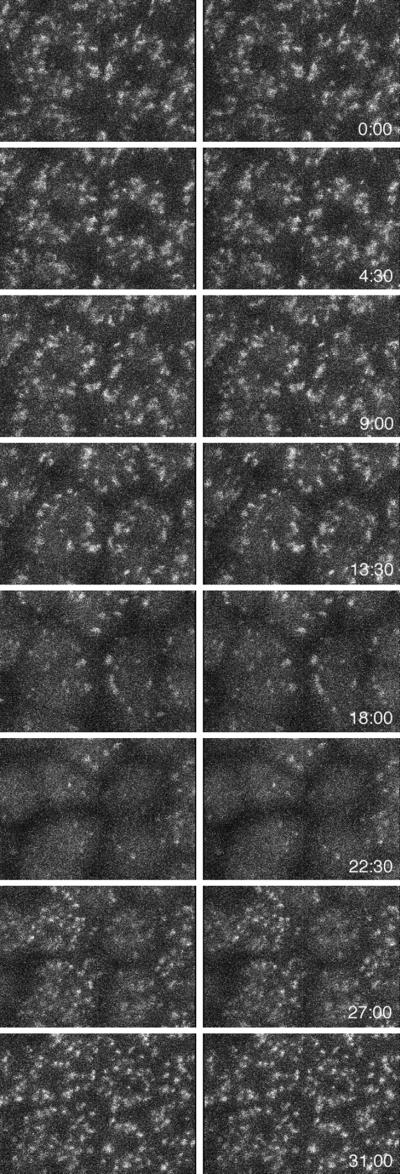

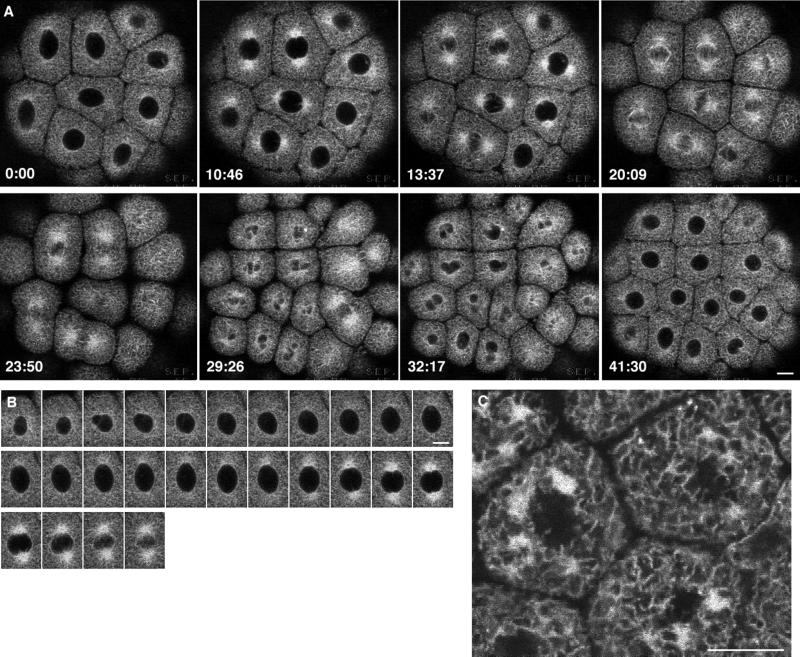

Figure 6.

Time-lapse sequence of the Golgi during mitosis. (A) Images of KDELRm-GFP were obtained every 30 s during the seventh cleavage; the timing of the images shown is indicated. (B) Time course of the number of Golgi spots in three different blastomeres. There was some uncertainty in counting. The Golgi that were located farther away from the focal plane gave rise to a progressively more hazy image, and sometimes it was difficult to determine whether an image corresponded to one or two separate Golgi. During interphase, the spots probably correspond to stacks seen by electron microscopy (Figure 2), but the average size of the spots is smaller during mitosis, and it is not known what they correspond toultrastructurally. Last, with this magnification, illumination level, and acquisition settings, the smaller spots seen in Figure 8 were not visible. For the measurements shown here, the spots counted were ≥1 μm in dimension and had a distinct outline. The data document a general trend, which is that the number of Golgi spots begins to decrease soon after NEBD, is at a minimum soon after cytokinesis is completed, and increases rapidly afterward. The original data are shown at http://www2.uchc.edu/mitosis. The top graph contains data from the cell shown in the image sequence. Bar, 10 μm.

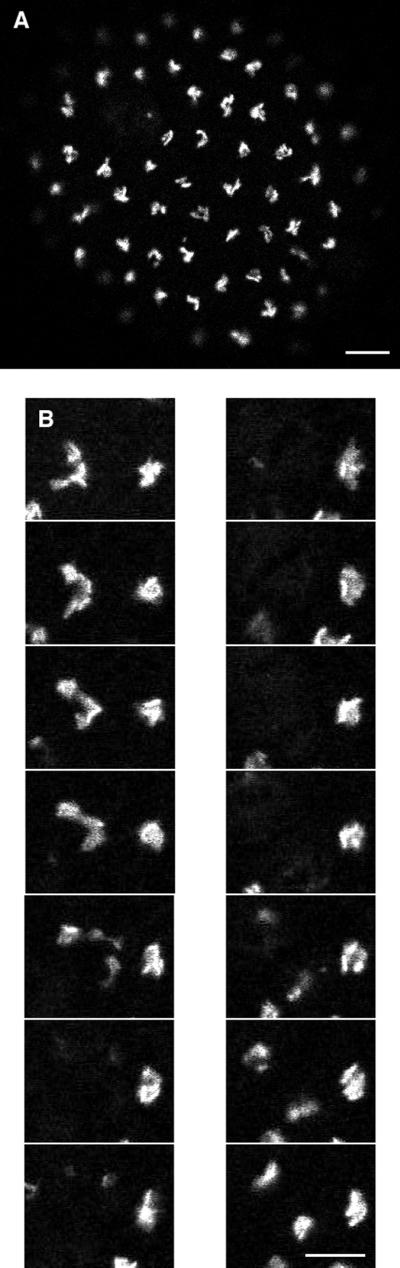

Figure 12.

(A) Low-magnification view of a whole embryo showing the Golgi after the 10th cleavage. The scattered spots in the cytoplasm have become a single aggregate in each cell. By focusing through the embryo, these aggregates were seen to be located at the apical side of each nucleus. This organization is first seen after the ninth cleavage. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Mitosis of apical Golgi. Images were obtained every 17 s during the 10th cleavage. Images shown are at 4-min 15-s intervals. The Golgi spreads from its compact organization and then becomes diffuse as the cell goes through mitosis. The Golgi then returns to its original organization after the cell has cleaved. Bar, 5 μm.

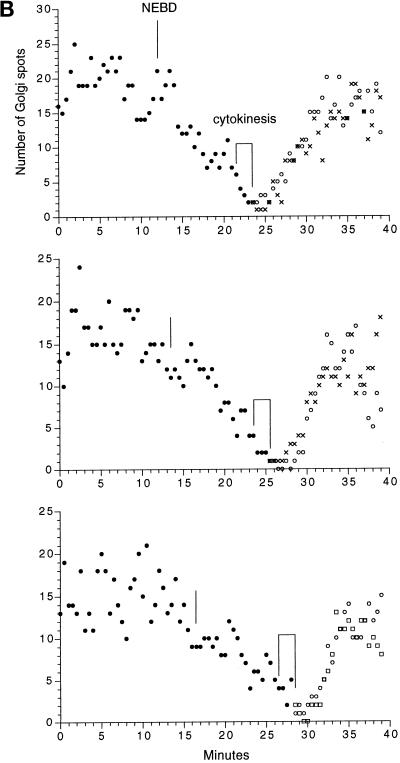

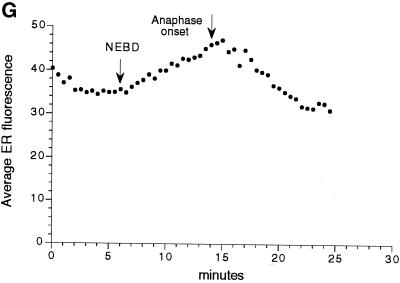

Figure 8.

Higher magnification of Galtase-GFP during mitosis. Cells were imaged with a 63× NA 1.4 objective lens as in Figure 5 but at zoom 3 instead of zoom 1. In addition, the laser illumination level was increased threefold, and the length of time for collecting fluorescence emission per pixel was increased threefold, so that the brightness of the image was increased ∼10-fold. As a consequence, the fluorescence from the Golgi was saturated, but the ER and other staining could be observed. The images are a two-frame average (slow scan = 3.1 s per frame) and are part of a sequence taken at 30-s intervals (the complete sequence can be viewed at http://terasaki.uchc.edu/mitosis). (A) Interphase, 6 min 30 s before NEBD of the seventh cleavage occurred. (B) Fifteen minutes after the first image, using identical instrument settings. Golgi spots of interphase cells are no longer prominent, but smaller spots are present throughout the cytoplasm. The ER pattern also appears to be brighter. (C) Twenty-four minutes after the first image. (D–F) The average fluorescence was determined within regions that contained only ER profiles. These areas excluded spots and were intended to measure Galtase-GFP fluorescence in the ER. (G) Average fluorescence versus time for each time point of this image sequence, using area tracings similar to that shown in D–F. The first time point corresponds to A and D, and the last time point corresponds to C and F. The data were used for calculating the ratio of fluorescence in the ER of untreated mitotic versus interphase cells. Bar, 10 μm.

Figure 11.

Effect of brefeldin A on Galtase GFP distribution. Seawater containing brefeldin A (5 μg/ml) was put into the chamber between the sixth and seventh cleavages. (A) Control image taken 4 min 30 s before change to brefeldin A. (B) Same region 36 min 30 s after brefeldin A. The blastomere has gone through the seventh cleavage, showing that brefeldin A does not block mitosis. Most of the Galtase GFP appears to be in the ER, and very few if any Golgi spots are present. Bar, 10 μm.

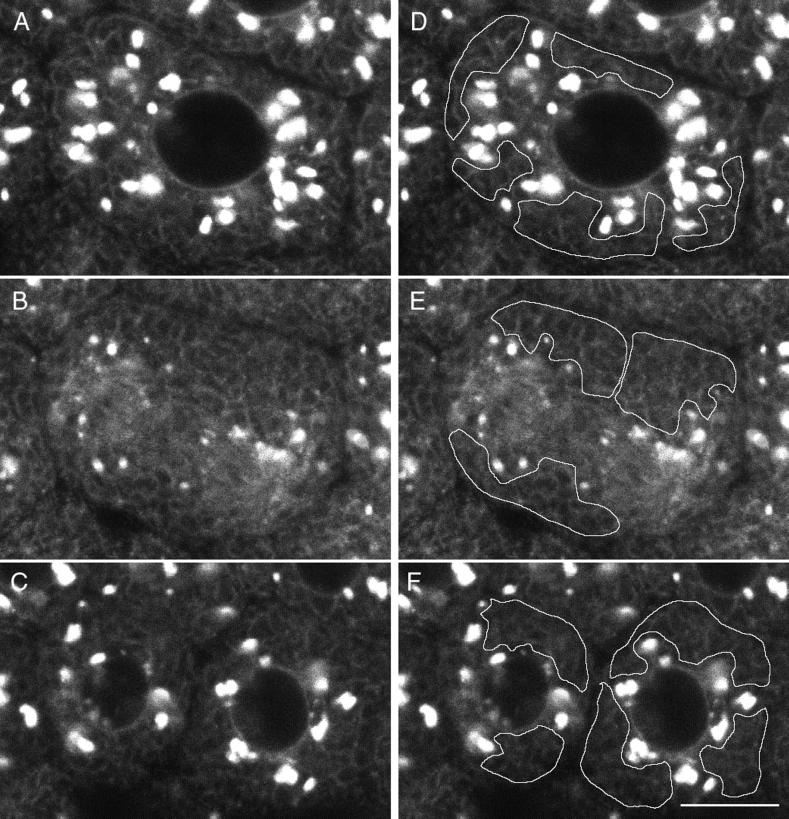

Figure 9.

Galtase-GFP distribution in blastomeres arrested in prometaphase. (A) Interphase, 6 min after nuclei reformed after the sixth cleavage. The seawater in the chamber was changed to seawater containing 1 μM nocodazole 2 min 30 s after this image was taken. (B) Thirty-six minutes after nocodazole. To monitor the effect of nocodazole, the embryo was imaged at low magnification, low laser illumination at 30-s intervals. NEBD of the seventh cleavage occurred ∼11 min after nocodazole was added to the chamber. The blastomere was imaged with identical laser intensity and instrument settings as in A. The fluorescence pattern appears to be coming largely from the ER, which is brighter than in the interphase cells. There are some bright spots scattered throughout the cell, but they are much fewer and smaller than in interphase cells. Bar, 10 μm.

The time-lapse z series sequence (see Figure 7) was obtained with an Olympus (Melville, NY) FluoView confocal microscope on an IX-70 inverted microscope. Time-lapse recordings of blastomere divisions (Table 1) were made using an Image 1/AT image processor (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). For making figures, the original images were cropped and adjusted for brightness and contrast in Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) and Instat (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) were used for statistical calculations and for making graphs.

Figure 7.

Time sequence of z series during mitosis of an embryo expressing KDELRm-GFP. z series sequences were obtained at 45-s intervals during the seventh cleavage and consisted of 11 sections 2 μm apart. Every sixth z series is shown here (4.5-min intervals). The z series stack for each time point has been projected as a stereo pair. This sequence shows that the decrease in the number of Golgi in one optical section seen in Figure 5 corresponds to a decrease in the number of Golgi throughout the cell rather than a redistribution of the Golgi out of the plane of the optical section.

Table 1.

Approximate timing of cell divisions in L. variegatus

| Cycle | Cells (n) | Duration | Cleavage | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1 | 1 :11 | 1st | 1 :11 |

| 2nd | 2 | 0 :31 | 2nd | 1 :43 |

| 3rd | 4 | 0 :31 | 3rd | 2 :14 |

| 4th | 8 | 0 :31 | 4th | 2 :45 |

| 5th | 16 | 0 :28 | 5th | 3 :13 |

| 6th | 32 | 0 :32 | 6th | 3 :46 |

| 7th | <64 | 0 :32 | 7th | 4 :18 |

| 8th | <128 | 0 :44 | 8th | ∼5 :02 |

| 9th | <256 | 0 :58 | 9th | ∼5 :52 |

| 10th | <512 | 1 :23 | 10th | ∼7 :22 |

| 11th | <1024 | Hatch | 8 :03 |

Average division times (hr:min) were determined from a time-lapse sequence of three embryos from one animal observed at ∼24°C. The division times are likely to vary in different animals and are also dependent on temperature, so that the times shown are meant to convey the general features of division times rather than to document them precisely. The early embryonic divisions are synchronous; but later divisions become less synchronous, particularly after the seventh cleavage: so that the division times for different blastomeres are more variable in the later stages. The total cell numbers are approximate for the later stages because several blastomeres at the vegetal pole withdraw form the cell cycle (Summers et al., 1993).

Electron Microscopy

Embryos were fixed for 1 h in 1% glutaraldehyde, which was made by diluting 8% glutaraldehyde in seawater (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Gibbstown, NJ). The eggs were changed to seawater and then postfixed for 1 h with 1% OsO4 and 0.8% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4. The eggs were rinsed thoroughly in distilled water and stained in 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h. They were dehydrated and embedded in Poly/Bed (Polysciences, Warington, PA). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined in a transmission electron microscope (CM-10; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

RESULTS

ER Dynamics

To examine the organization of the ER during the cell cycle, GFP was targeted to the lumen of the ER of sea urchin embryos. GFP was previously targeted to the ER of starfish oocytes by use of the construct GFP-KDEL (Terasaki et al., 1996). This construct contains a signal sequence from a native sea urchin lumenal protein, ECast/PDI (Lucero et al., 1994), followed by the S65T mutant of GFP (Heim et al., 1995) with a KDEL ER retention sequence at the C-terminal end (Munro and Pelham, 1987). mRNA coding for GFP-KDEL was injected into unfertilized sea urchin eggs. GFP fluorescence developed only if the eggs were subsequently fertilized. This is consistent with findings that the overall protein synthesis rate is low in unfertilized eggs and increases up to 100-fold after fertilization (Regier and Kafatos, 1977). After fertilization, GFP fluorescence increased gradually so that it was bright enough to be imaged clearly by about the fifth cell cycle. An approximate time table of the cell division cycles is given in Table 1. Because there is considerable difference in the developmental fates of the different blastomeres (Horstadius, 1973), only blastomeres at the animal pole region were imaged in this study (see MATERIALS AND METHODS).

The ER organization underwent striking changes as the cells progressed through the cell cycle (Figure 1A). In interphase, just after exiting from mitosis, the ER appeared to be uniformly distributed. A pattern representative of cisternae throughout the interior was seen, as well as the outline of the interphase nucleus. ER gradually accumulated at the mitotic poles before nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) (Figure 1B) and remained concentrated there as the cells formed a mitotic apparatus and went through mitosis. The accumulation of ER at the mitotic poles, which has been seen previously by electron microscopy (Harris, 1975), immunofluorescence (Henson et al., 1989), and dye labeling, showed that it originated with the sperm aster (Terasaki and Jaffe, 1991). The microtubule-depolymerizing drug nocodazole (1 μM) did not prevent accumulation of ER membranes, but the accumulations were irregular and not bipolar (Figure 1C). As the cells exited mitosis, many small “chromosome vesicles” formed first (Figure 1A, second row, second panel from left; Ito et al., 1981), which then fused to form a single large nucleus.

Figure 1.

(A) Changes in ER organization during the cell cycle of sea urchin embryo blastomeres expressing GFP-KDEL. Images were obtained at 10.2-s intervals as the blastomeres went through the sixth cleavage; the timing for images shown is indicated. The embryo was oriented with the animal pole next to the coverslip, as in all other figures. The middle blastomere in the top row is shown in the next panel. (B) Closer-spaced time intervals (1 min) of the blastomere denoted in A to show the progression of ER accumulation at mitotic poles. The first image is soon after the nucleus has begun to reform. The image at the end of the top row is 20 s before the first image of A, whereas the second to last image of the bottom row is 10 s after the third image of A. (C) Nocodazole (1 μM) was perfused into the injection chamber during the interphase after the sixth cleavage of another embryo. The cells were imaged 25 min after perfusion, when it was clear that the mitotic cycle had been halted. Bars, 10 μm.

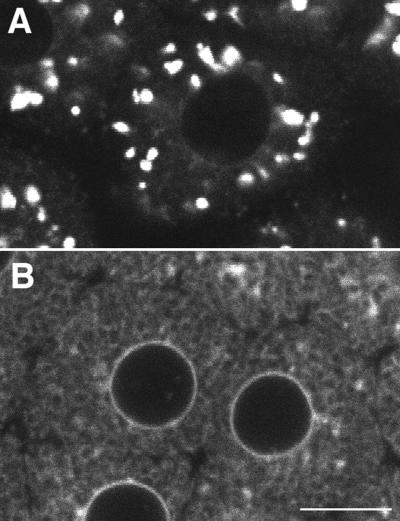

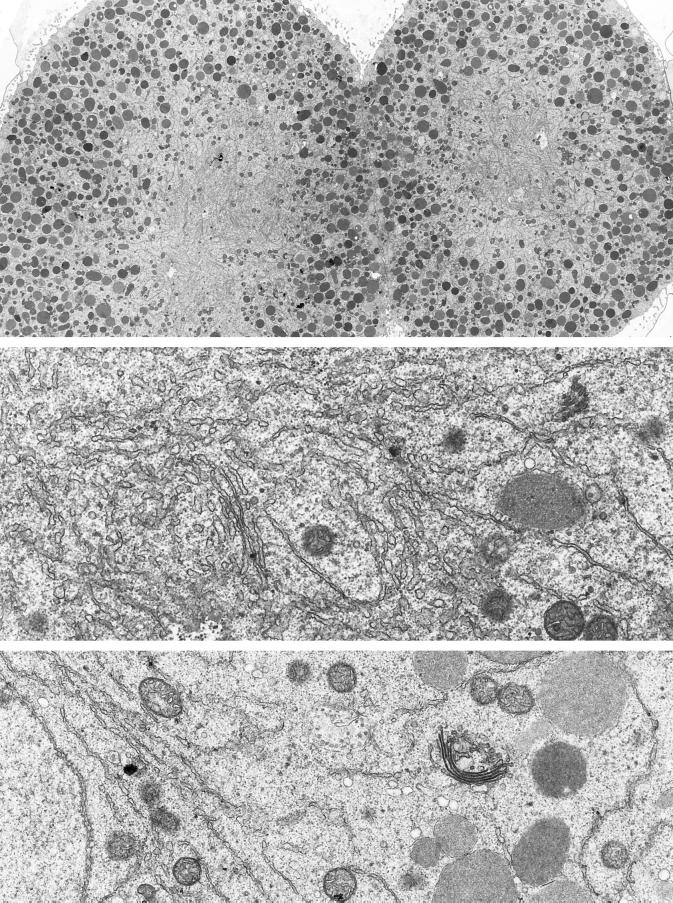

Electron microscopy shows that the mitotic pole region has a high density of membranes that have characteristics of the ER (Figure 2, top and middle panels). There were also some mitochondria, but the yolk platelets were excluded from this region. The fluorescence in different regions of GFP-KDEL-expressing cells was quantitated in single optical sections through the center of the blastomeres. The ratio of fluorescence in the mitotic pole region versus the peripheral region was 2.32 ± 0.27 (n = 13). This is evidence that the ER is ∼2.3 times more concentrated in the pole region than outside. Cytosol was also present in a higher concentration in the mitotic pole region primarily because of the exclusion of yolk platelets. The question then arose of whether the ER is concentrated to the same degree as the cytosol. The relative concentration of cytosol was estimated by quantitating fluorescence in eggs injected with 10-kDa rhodamine dextran. The ratio of fluorescence in the mitotic pole region versus the peripheral region was 1.69 ± 0.08 (n = 12). The ER was therefore concentrated in the mitotic pole region to a somewhat greater degree than the cytosol.

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy of ER and Golgi in sea urchin embryos (5 h after fertilization). Top panel, ER is accumulated in the region of the mitotic poles. Yolk platelets (large, dark-staining organelles) are excluded, but some mitochondria are present (magnification, 2070×). Middle panel, higher-magnification view of the accumulated ER in the region of a mitotic pole (magnification, 21,360×). Bottom panel, typical appearance of a Golgi stack. Golgi stacks are scattered throughout the cytoplasm and do not appear to be connected. The Golgi stack shown here is ∼1.2 μm long in its widest dimension. The nucleus is seen on the left, indicating that this blastomere was fixed during interphase (magnification, 18,000×).

During the later parts of mitosis, the appearance of the ER away from the mitotic apparatus did not change drastically (Figure 3). In particular, the ER did not seem to become vesiculated as occurs in rat thyroid epithelium (Zeligs and Wollman, 1979). To assess ER continuity during mitosis, photobleaching techniques were used. GFP-KDEL was bleached by intense illumination of a small region of a cell, and the behavior of the unbleached GFP-KDEL was observed. We previously used photobleaching to provide evidence that the ER becomes transiently discontinuous at fertilization in starfish eggs (Terasaki et al., 1996).

Using a fluorescence redistribution after photobleaching (FRAP) protocol an ∼8 × 10-μm region was bleached, and the fluorescence in the bleached zone was monitored. The bleached zone recovered to 90 ± 5% (n = 6) in 27 s in interphase cells and to 86 ± 14% in 27 s in mitotic cells (n = 6). If GFP-KDEL were present in vesicles, the recovery should be much slower. For instance, fluorescence in endosomes (labeled by a 15-min pulse with 0.3 mg/ml 10-kDa fluorescein dextran in the seawater) recovered only 6 ± 8% (n = 6) in 82 s in interphase cells. The rapid recovery of GFP-KDEL indicates that continuous pathways for diffusion of GFP-KDEL exist between the bleached and unbleached regions in the mitotic cells.

To assess the continuity of the ER over the entire cell, a variation of FRAP was used (FLIP; Cole et al., 1996b; Ellenberg et al., 1997). In this protocol, a small region is bleached repetitively with short intervals of recovery that allow for fluorescence redistribution. During the recovery intervals, cells are imaged with one scan at low-intensity illumination to monitor the fluorescence redistribution. A small region of interphase or mitotic cells was subjected to nine cycles of photobleaching and recovery over a total period of 2.5 min. The GFP-KDEL fluorescence was reduced uniformly throughout the cell (Figure 3). This indicates that in both interphase and mitotic cells, most if not all of the GFP-KDEL exchanges rapidly by diffusion with the bleached region, as is consistent with molecules in a continuous membrane system. The results of the photobleaching experiments thus provide strong evidence that the ER remains continuous during mitosis of sea urchin egg blastomeres.

NEBD

When viewed by transmitted light microscopy, the smooth, distinct outline of the nucleus suddenly becomes irregular during mitosis. This process is classically called NEBD, and the term “NEBD” is used to refer to the time at which this change occurs.

Before NEBD, when the sides of the nucleus were still smooth, finger-like projections of GFP-KDEL staining extended inward into the nuclear region from the two mitotic poles. This was also seen in eggs labeled with a DiI-saturated oil droplet to stain the ER (Terasaki and Jaffe, 1991). These structures correspond to the “nuclear envelope projections” seen in sea urchin embryos by transmitted light microscopy, which appear 2–3 min before NEBD (Hamaguchi et al., 1993). In the GFP-KDEL- or DiI-labeled blastomeres, the finger-like projections extended rapidly (within ∼10 s), remained the same length for longer periods, and sometimes moved from side to side or appeared to move out of focus (Figure 4, left panels). For ∼2–3 min, the projections were present, whereas the sides of the nucleus (located equatorial to the mitotic poles) remained smooth. There was then an abrupt change as the sides of the nuclear envelope became wrinkled (NEBD) and the ER underwent a general movement into area formerly enclosed by the nuclear envelope.

Hamaguchi et al. (1993) interpreted the nuclear envelope projections as indentations of the nuclear envelope caused by microtubules. However, it was possible that the microtubules penetrated the nuclear envelope, and that the nuclear envelope projections are ER tubules extended along the microtubules. To resolve this issue, large fluorescent dextrans, which do not cross the nuclear pores, were used to assess the permeability of the nuclear envelope (Terasaki, 1994). After mitosis, the newly forming nucleus excludes large dextrans (Swanson and McNeil, 1987), so that large dextrans can be injected into an egg before fertilization and be used to monitor dextran entry during each successive mitosis. Eggs were injected with DiI and with 70-kDa fluorescein dextran as a marker for nuclear envelope permeability. Time-lapse imaging of the two labels (Figure 4) showed that the large dextran began to enter ∼30 s before the lateral outline of the nucleus became crumpled (Figure 4, D vs. G and H). This shows that a change in the permeability barrier of the nuclear envelope begins ∼30 s before the time that is designated as NEBD. This appears to be similar qualitatively to the starfish oocyte germinal vesicle during meiotic maturation, in which a slow entry of 70-kDa dextran begins ∼5 min before rapid entry at NEBD (Terasaki, 1994); in that study, it was suggested that the slow first phase of entry is through nuclear pores and the rapid phase occurs after disruption of the double membrane bilayer. In addition, the finger-like nuclear envelope projections are present 1.5–2.0 min before any change in nuclear envelope permeability. This is strong evidence that the nuclear envelope projections are indentations of an intact nuclear envelope by microtubules.

Golgi Localization

GFP was targeted to the Golgi apparatus of sea urchin embryos by using two chimeras that were previously used with HeLa and other cultured cells (Cole et al., 1996b). ELP (Hsu et al., 1992) is the human homologue of yeast erd2, a protein that cycles between the Golgi apparatus and the ER and is thought to retrieve proteins containing the KDEL ER retention sequence (Semenza et al., 1990). Mutants of erd2 that remain in the Golgi have been generated (Townsley et al., 1993). KDELRm-GFP (Cole et al., 1996b) consists of such a mutant ELP and the S65T mutant of GFP (Heim et al., 1995). Galtase-GFP consists of the first N-terminal 60 amino acids of human galactosyl transferase, a resident protein of the Golgi involved in carbohydrate processing, followed by the S65T mutant of GFP (Cole et al., 1996b).

mRNA coding for KDELRm-GFP or Galtase-GFP was injected into unfertilized sea urchin eggs. Both resulted in similar staining patterns. As with GFP-KDEL, no fluorescence developed if the eggs were left unfertilized. After fertilization, there was a 2-h lag followed by a linear increase of fluorescence for at least 8 h (Figure 5A). The lag period is probably due to the time for several processes to occur: the postfertilization increase in protein synthesis rates, synthesis of the chimera, and the folding of the chimera into a fluorescent conformation. Although in other systems, protein synthesis is thought to halt or slow down during mitosis, there has been no evidence for this in sea urchin embryos.

GFP fluorescence was bright enough to be imaged in intracellular structures by about the fourth or fifth cell cycle. Fluorescent spots of different sizes (∼2–5 μm) and shapes were scattered throughout the cytoplasm in interphase (Figure 5, B and C), along with some background fluorescence. Electron microscopy showed that Golgi stacks are present throughout the cell in unfertilized eggs and in the early cell cycles (Figure 2, bottom panel). Furthermore, when blastomeres expressing GFP-Golgi were subjected to a FLIP protocol, the Golgi spots outside of the photobleach area were not eliminated (our unpublished results). Thus, each bright fluorescent spot very probably corresponds to a Golgi stack.

In addition to the fluorescent spots, a lower level of labeling was present throughout the cell. When higher-intensity illumination was used, the fluorescence had the same pattern as GFP-KDEL labeling, indicating that KDELRm-GFP or Galtase-GFP was also present in the ER (see Figures 8A and 9A). The fluorescence in the ER is likely to be from newly synthesized chimera molecules that had not yet progressed to the Golgi or from chimera molecules that are recycling between ER and the Golgi (Cole et al., 1998; Storrie et al., 1998; Wooding and Pelham, 1998).

The total number of Golgi spots in blastomeres during interphase of the 32-, 64-, and 128-cell stages were counted from z series sequences. It was difficult to make an accurate count because of a large difference in the sizes of fluorescent spots; in several cases, it was not clear whether a large, apparently multilobed “spot” should be counted as one or as several Golgi. With these difficulties in mind, the data indicate that the number of Golgi per blastomere decreases from generation to generation; it is possible that the total number of Golgi per embryo is constant at this stage of development (Table 2); i.e., the number per blastomere may be halved after each division.

Table 2.

Average total number of Golgi per blastomere

| Stage | No. of Golgi |

|---|---|

| 32-cell | 150 ± 15 (n = 4) |

| 64-cell | 81 ± 16 (n = 4) |

| 128-cell | 32 ± 9 (n = 8) |

Average number ± SD of Golgi per blastomere determined from z series sequences (0.54-μm steps).

Changes in Golgi during Mitosis

In time-lapse sequences, the number of Golgi spots decreased cyclically as the cells went through the mitotic phase of the cell cycle (Figure 6A). The number of Golgi spots began to decrease after NEBD and appeared to be at a minimum just after cytokinesis (Figure 6B). At about the time the nucleus reformed, the Golgi spots began to reappear and gradually became more numerous and larger. These changes were observed during the fifth through eighth cell cleavages (labeling in earlier cleavages was too dim, and the behavior in later cleavages is described in the next section). To exclude the possibility that the number of Golgi spots decreased because of movement of Golgi out of the confocal section, a time-lapse z series of optical sections was taken as the blastomeres went through mitosis. Stereo projections of the z series images showed that there were much fewer Golgi spots throughout the whole cell at the time of cytokinesis (Figure 7).

To investigate the fate of the GFP chimeras during mitosis, Galtase-GFP-expressing blastomeres were imaged at higher magnification and illumination levels (Figure 8). Illumination levels were approximately three times, and the pixel dwell time (the time that fluorescence emission is integrated per pixel) was three times longer, so the image is ∼10× brighter. When blastomeres in interphase were imaged with these conditions, the Golgi labeling was saturated, but the ER pattern became clearly visible (Figure 8, A and C). During mitosis, the ER was also visible, and there were small bright spots that were not detectable in the low-magnification images (compare Figures 6 and 8B). In time-lapse sequences, the small spots appeared to be derived from the interphase Golgi spots because they tended to be more abundant in regions where the Golgi spots were formerly located. The amount of fluorescence in the small spots was clearly not enough to account for all of the fluorescence in interphase Golgi spots. The dense staining in the mitotic pole regions corresponds well to GFP-KDEL staining of the ER (Figure 1), but staining details cannot be resolved, so Galtase-GFP may be present in other organelles in these regions. In the peripheral regions, there appeared to be no readily identifiable staining other than ER.

The ER became noticeably brighter during mitosis and then became dimmer in the next interphase (Figure 8). This suggested that a significant fraction of the Galtase-GFP becomes redistributed to the ER during mitosis. Further evidence for redistribution to the ER was obtained from cells blocked in mitosis by the microtubule-depolymerizing drug nocodazole. Galtase-GFP-expressing embryos were exposed to nocodazole (1 μM) during the interphase before the seventh cleavage. Previous studies have reported that microtubule-depolymerizing drugs prevent chromosome separation and cytokinesis while slowing down the DNA and centrosomal replication cycles (Sluder et al., 1986). The blastomeres underwent NEBD but did not form a mitotic spindle. The number of small spots decreased with time in the nocodazole-treated cells. After 30–40 min in nocodazole, there were only a few identifiable small spots, and aside from this labeling, only the ER appeared to be labeled (Figure 9). Photobleaching was then used to address whether the Galtase-GFP was present in a continuous or discrete membrane compartment in the nocodazole-treated cells. When cells were photobleached repetitively with a FLIP protocol, the fluorescence throughout the cell became reduced (Figure 10) just as the FLIP protocol reduced GFP-KDEL staining in cells (Figure 3). These experiments provide strong evidence that Golgi proteins become redistributed primarily to the ER in nocodazole-treated cells.

Quantitative measurements of total amounts of proteins in ER and Golgi have recently been made in cultured cells; in these cells, the Golgi and ER are located in regions that can be distinguished fairly readily, and the total fluorescence can be collected in one or a few confocal optical sections (Hirschberg et al., 1998). An attempt was made to quantitate the redistribution of Galtase-GFP to the ER during sea urchin blastomere mitosis.

Galtase-GFP was deliberately redistributed to the ER by the use of brefeldin A, a drug that causes a rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER of many cell types (Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1989). Brefeldin A did not affect the timing of the sea urchin embryo cell cycle, and embryos developed up to the hatching stage (see next section). Exposure of embryos in interphase of the sixth cell cycle to brefeldin A (5 μg/ml) caused most of the Golgi spots to disappear and prominent staining of the ER 30 min later in interphase of the seventh cell cycle (Figure 11). The average brightness was determined in regions in which only ER was visible. There was an increase of 2.48 ± 0.41-fold (mean ± SD; n = 9) after 30 min of brefeldin A treatment. Because the total amount of Galtase-GFP in the embryo increases by ∼26% in the 30-min interval between the sixth and seventh interphase (see MATERIALS AND METHODS), this corresponds to a 2.5/1.26 = 2.0-fold increase. The ER volume is probably much larger than the Golgi volume, so the 2.0-fold increase implies that the amount of Galtase-GFP in the Golgi and ER are approximately equal in these cells at this stage of development. For instance, if the ER were 10 times the volume of the Golgi, and both contained the same amount of Galtase-GFP, then a complete transfer of the Golgi would result in a 1.8-fold increase in ER concentration (or, with the same volume ratio, if there were 1.2 times as much Galtase-GFP in the Golgi as in the ER, there would be a 2.0-fold increase in ER concentration).

In interphase versus nocodazole-treated cells, the average intensity in ER-containing regions increased 1.96 ± 0.15-fold (n = 5). This value is an underestimate, because the fluorescence in the clumps of concentrated ER was not measured. The amount of new Galtase-GFP added to the ER by protein synthesis is 26% in 30 min, so that the amount of Golgi Galtase-GFP that transfers to the ER in nocodazole-treated cells is estimated to cause an increase of at least 1.70-fold in Galtase-GFP in the ER.

Image sequences (30-s intervals) of untreated cells progressing through mitosis were made (Figure 8). Average intensity measurements were made in peripheral cytoplasm, not in the mitotic pole regions, where it is difficult to distinguish between ER and Golgi staining (Figure 8G). There was a 1.36 ± 0.07-fold increase (n = 5; this value is significantly different from 1.0, p = 0.0004) in average ER brightness from just before NEBD to a maximum during anaphase (average time interval, 9.1 min). Because the measurements of large regions of cytoplasm could also include fluorescence from vesicles too small to be imaged, measurements also were made of traced ER profiles. These gave higher-intensity values, but the ratio of increase was the same (both 1.34 for the cell shown in Figure 8). This is evidence that the measurements over large regions in which only the ER pattern is visible give a representative value for the fluorescence in the ER.

The estimate for increase in ER fluorescence must be corrected for the increase in Galtase-GFP because of synthesis. Assuming that Galtase-GFP is synthesized and folds to a fluorescent conformation at a constant rate through the cell cycle, there is an 8% increase in Galtase-GFP in the embryo for a 9-min interval (at ∼4 h; see Table 1). A block of ER-to-Golgi transport during mitosis (Featherstone et al., 1985) would lead to an increase of Galtase-GFP only in the ER. Because the ER contains approximately the same amount of Galtase-GFP as the Golgi (see above), a complete block of ER-to-Golgi transport that occurred at NEBD would lead to a 16% increase in signal within the ER. With this subtracted, the increase in brightness of the ER corresponds to a redistribution of at least 20% of the Golgi to the ER in 9 min. This estimate does not take into account the high density of ER at the mitotic poles.

It would be interesting to quantitate the amount of Galtase-GFP in the Golgi or Golgi-derived organelles during mitosis, but the Golgi image is saturated under the conditions required to see the small spots. There is also uncertainty about which of the small spots correspond to out-of-focus Golgi-derived organelles or regional accumulations in the ER. If it were possible to make this measurement, the fluorescence in the Golgi and ER could be compared with the total fluorescence to determine the fraction of Galtase GFP in small vesicles that cannot be imaged. It would also be possible to address whether there is significant degradation of Galtase-GFP, although this seems unlikely.

The loss of Golgi spots at low magnification, the increase in ER brightness at high magnification, the larger increase in ER brightness when mitosis is prolonged in nocodazole, and the results of the FLIP experiment in nocodazole all are consistent with a significant redistribution of the Golgi to the ER during mitosis.

Golgi Reorganization after the Ninth Cleavage

After the ninth cleavage, the Golgi distribution became strikingly transformed to a single aggregate (Figure 12A). This distribution was seen on both the animal and vegetal halves of the embryo and was maintained after the 10th cleavage. By focusing through the embryo, this aggregate is located between the nucleus and the side of the cell facing the outside of the blastula, away from the blastocoel. Thus the Golgi is located on the apical side of the nucleus, which is the organization typical in epithelia (Fawcett, 1994). An apical Golgi was seen by electron microscopy in an unhatched sea urchin blastula (Gibbins et al., 1969), although the stage of development was not determined precisely in that study. A time sequence of z series images showed that several large Golgi spots formed after the ninth cleavage and then gradually moved together over ∼40 min (our unpublished results). The Golgi was imaged during the 10th cleavage (the last cleavage before hatching) (Figure 12B). The Golgi appeared to move apart from its compact distribution, and then the bright fluorescent structure became lost. The bright fluorescence returned after cytokinesis and became restored to the compact apical structure.

The sea urchin embryo hatches after the 10th cleavage (Dan et al., 1980). Hatching is accomplished by the matrix metalloendoproteinase HE, which digests the fertilization envelope (Lepage and Gache, 1989, 1990; Lepage et al., 1992). Immunofluorescence localization is consistent with HE synthesis in the ER and passage through an apical Golgi (Lepage et al., 1992). HE is presumably packaged into vesicles and secreted at the apical end of the cells. Consistent with this, brefeldin A (0.1–0.2 μg/ml continuous exposure) caused dissolution of the Golgi (our unpublished results) and prevented hatching (Skoufias et al., 1991).

DISCUSSION

ER Remains Continuous during the Cell Cycle

GFP was targeted to the ER by injecting mRNA coding for the construct GFP-KDEL. The bulk of the ER retains its appearance throughout the cell cycle. There is a cyclical accumulation of the ER at the mitotic poles, which may have a regulatory role through its Ca-regulating capacities (Groigno and Whitaker, 1998) or interaction with microtubules (Hepler and Wolniak, 1984).

Photobleaching has been successfully used to show that ER of starfish eggs becomes transiently discontinuous during fertilization (Terasaki et al., 1996). Both FRAP and FLIP protocols for photobleaching provide strong evidence that the ER remains continuous through the cell cycle. This conclusion differs from a commonly held view that the ER becomes vesiculated during mitosis. The best evidence for this view is from a well-documented study in rat thyroid epithelium (Zeligs and Wollman, 1979). It is worth quoting from this study of cells in tissues (Zeligs and Wollman, 1979, p. 67): “Vesiculation of the ER similar to that observed in the present study has been noted or illustrated for only a small number of mitotic cell types. This may reflect in part the paucity of studies on well-differentiated cells with large quantities of RER, but also indicates that vesiculation of RER is not a general occurrence in all mitotic cells. In fact, in the thyroid glands employed in the present study, several types of interstitial cells (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and pericytes) were observed in various stages of mitosis, with essentially interphase RER morphology.”

Thus it appears that the ER may either become vesiculated or remain continuous during mitosis in different cell types, whether in culture or in tissues, and that this must be checked experimentally. There is recent evidence that the nuclear envelope does not vesiculate but is resorbed into a continuous ER in cultured NRK, COS-7, HeLa, and 3T3 cells (Ellenberg et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1997). Certainly, it does not appear that vesiculation is physically required to partition the ER. In sea urchin blastomeres, the manner of partitioning appears to be simply that the ER is pushed aside into either of the future daughter cells by the slowly advancing cleavage furrow.

NEBD

GFP-KDEL- and DiI-labeled membrane fingers projected from the mitotic pole regions into the nucleus 2–3 min before NEBD. These structures closely resemble nuclear envelope projections seen previously by transmitted light microscopy, also in sea urchin embryos (Hamaguchi et al., 1993). Hamaguchi et al. (1993) interpreted these structures to be microtubule-driven indentations of the nuclear envelope. Similar projections have also been seen by light microscopy in grasshopper (Chortophaga) spermatocytes (Nicklas, personal communication). The GFP-KDEL and DiI labeling provide definitive evidence that the projections are membranous.

An unresolved issue from the study by Hamaguchi et al. (1993) is the state of the permeability barrier of the nuclear envelope at the time the projections appear. It is possible, for instance, that microtubules have pierced the nuclear envelope and are serving as tracks for plus end-directed elongation of ER tubules (Terasaki et al., 1986; Dailey and Bridgman, 1991). Use of fluorescein-labeled 70-kDa dextran (FDx) to monitor nuclear envelope permeability (Terasaki, 1994) showed that the nuclear envelope projections are part of an intact nuclear envelope that still functions as a permeability barrier. It is very likely that the nuclear envelope projections are caused by microtubules pushing in the envelope.

Georgatos et al. (1997) described microtubule-associated indentations of the nuclear envelope in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells and normal rat kidney cells in culture, although there was only one large, wide indentation on each side of the nucleus. Microtubule-driven deformations of the nuclear envelope may therefore be a common feature during mitosis of insect, echinoderm, and mammalian cells. Hamaguchi et al. (1993) and Georgatos et al. (1997) both speculate that they could be involved in positioning chromosomes. Possibly the microtubules in the projections could remain associated with nuclear envelope remnants after NEBD and have a specific role during mitosis.

Golgi Structure during the Cell Cycle

Electron microscopy shows small isolated Golgi stacks scattered throughout the cytoplasm of sea urchin blastomeres. This corresponds well with fluorescence imaging of the Golgi-targeted chimeras GFP-KDELRm and Galtase-GFP. Thus, the Golgi is not a single-copy organelle in sea urchin blastomeres. Because there are multiple copies of the Golgi, there is no apparent reason for them to become vesiculated or to be disassembled to partition them to daughter cells. Even so, there is a fundamental change in the Golgi, because most of the Golgi spots seem to disappear during mitosis in low-magnification time-lapse image sequences.

What happens to the Golgi proteins during mitosis? At higher levels of magnification and illumination, smaller spots are seen. At these levels, the Golgi spots remaining from interphase are saturated, making it difficult to quantify the amounts present in the smaller spots. It is generally agreed that small vesicles > ∼100 nm cannot be imaged by this type of microscopy. There is also a dense accumulation of membranes in the mitotic pole regions, where organelles cannot be resolved. Thus, a complete accounting of the fate of Galtase-GFP during mitosis was not possible in sea urchin blastomeres with our confocal microscope imaging system.

However, it was possible, at the higher magnification and illumination levels, to visualize parts of the ER fairly clearly. The fluorescence in the peripheral ER was noticeably brighter during mitosis and then became dimmer as the cells exited mitosis. The apparent redistribution to the ER was accentuated by the microtubule-depolymerizing drug nocodazole. When the M phase, which lasts ∼15 min, was prolonged by a further 15 min with nocodazole, there was almost complete elimination of Golgi spots, and the ER was much brighter. FLIP experiments on nocodazole-treated cells indicate that Galtase-GFP was present in the continuous membranes of the ER. As described in RESULTS, there are several obstacles to obtaining quantitative values. With these reservations in mind, there was an estimated transfer of at least 20% of the Golgi to the ER during the ∼9 min between NEBD and anaphase of the seventh cleavage.

The quantitation of Galtase-GFP in the ER leaves unresolved what happens to the rest of the Galtase-GFP during mitosis. There is nothing in this study that rules out the possibility that a majority of the Galtase-GFP is present in vesicles. What this study does conclude is that some of the Golgi is redistributed to the ER during mitosis. A similar conclusion was also reached by Zaal et al. (1999), who have used Golgi-targeted GFP chimeras to investigate the Golgi in cultured mammalian cells. It should be pointed out that the effect of nocodazole on sea urchin mitosis supports the idea that redistribution of Golgi to the ER is the central process during mitosis, although it does not normally go to completion.

During mitosis, there are changes in cellular processes and organization that are not directly related to partitioning. Several physiological processes have been found to be inhibited during mitosis; for instance, endocytic membrane traffic ceases (Berlin et al., 1978), and signal transduction pathways turn off (Preston et al., 1991). It may be appropriate to think of mitosis as a period when many highly regulated cellular processes revert to a basal state so that cellular resources are used for partitioning the genetic material. Recent evidence indicates that the Golgi is sustained by a recycling pathway from the ER (Cole et al., 1998; Lippincott-Schwartz et al., 1998; Storrie et al., 1998). Evidence from the present study is consistent with the idea that this recycling pathway is slowed or completely shut down during mitosis in a way that results in a net redistribution of Golgi back into the ER.

Transformation to Apical Golgi

After the ninth cleavage, the multiple Golgi coalesce to form a single apical Golgi. There may be a simple mechanism for establishing the apical Golgi. The central location of Golgi in mammalian fibroblasts is thought to be due to dynein driven movement along microtubules (Cole et al., 1996a, 1998; Burkhardt et al., 1997; Presley et al., 1997, 1998; Storrie et al., 1998). It seems possible that the scattered Golgi in sea urchin blastomeres in early development are due to lack of interaction with microtubule motors, and that the appearance of the apical Golgi after the ninth cleavage is due to acquisition by the Golgi of the ability to bind to dynein.

The sea urchin embryo develops into a ciliated epithelium at about the same time that it secretes a major product from its apical surface. The transformation, which develops within a few hours at most, is rapid compared with the transformation in mouse embryos (Collins and Fleming, 1995) and Madin–Darby canine kidney cells (Bacallao et al., 1989). The sea urchin embryo may provide another useful system for understanding how epithelial cell characteristics develop and are regulated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank John Hammer (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) and Nelson Cole and Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD], NIH) for supplying the GFP chimeras, Art Hand (Central Electron Microscopy Facility, University of Connecticut Health Center) for electron microscopy, and Kristien Zaal (NICHD, NIH) for help with the FLIP experiment. I also thank John Morrill (New College) for informative discussions on blastulae, Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Kristien Zaal, and Jan Ellenberg (NICHD, NIH) for discussions of results, Laurinda Jaffe (University of Connecticut Health Center) for reading the manuscript, and Olympus for loan of the confocal microscope. I also thank Tom Reese (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH) for use of his facilities at the Marine Biological Laboratory. This work was supported by a grant from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Acharya U, Mallabiabarrena A, Acharya JK, Malhotra V. Signaling via mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) is required for Golgi fragmentation during mitosis. Cell. 1998;92:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson JD. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 3rd ed. New York: Garland Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Aridor M, Bannykh SJ, Rowe T, Balch WE. Sequential coupling between COPII and COPI vesicle coates in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:875–893. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacallao R, Antony C, Dotti C, Karsenti E, Stelzer EH, Simons K. The subcellular organization of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells during the formation of a polarized epithelium. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2817–2832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin RD, Oliver JM, Water RF. Surface functions during mitosis 1: phagocytosis, pinocytosis and mobility of surface-bound ConA. Cell. 1978;15:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B, Griffiths G, Reggio H, Louvard D, Warren G. A monoclonal antibody against a 135K Golgi membrane protein. EMBO J. 1982;1:1621–1628. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt JK, Echeverri CJ, Nilsson T, Vallee RB. Overexpression of the dynamitin (p50) subunit of the dynactin complex disrupts dynein-dependent maintenance of membrane organelle distribution. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:469–484. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole NB, Sciaky N, Marotta A, Song J, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Golgi dispersal during microtubule disruption: regeneration of Golgi stacks at peripheral endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Mol Biol Cell. 1996a;7:631–650. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole N, Smith C, Sciaky N, Terasaki M, Edidin M, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Lateral diffusion of Golgi proteins in Golgi and ER membranes of living cells. Science. 1996b;273:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole NB, Ellenberg J, Song J, DiEuliis D, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Retrograde transport of Golgi-localized proteins to the ER. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JE, Fleming TP. Epithelial differentiation in the mouse preimplantation embryo: making adhesive cell contacts for the first time. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey ME, Bridgman PC. Structure and organization of membrane organelles along distal microtubule segments in growth cones. J Neurosci Res. 1991;30:242–258. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490300125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan K, Tanaka S, Yamazaki K, Kato Y. Cell cycle study up to the time of hatching in the embryos of the sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus. Dev Growth Differ. 1980;22:589–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1980.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg J, Siggia ED, Moreira JE, Smith CL, Presley JF, Worman HJ, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1193–1206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki T, Ponnambalam S, Prescott AR, Clausen H, Tang B-L, Hong W, Lucocq JM. Forward and retrograde trafficking in mitotic animal cells. ER-Golgi transport arrest restricts protein export from the ER into COPII-coated structures. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:589–600. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett DW. A Textbook of Histology. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone C, Griffiths G, Warren G. Newly synthesized G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus is not transported to the Golgi complex in mitotic cells. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2036–2046. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuseler JW. Repetitive procurement of mature gametes from individual sea stars and sea urchins. J Cell Biol. 1973;57:879–881. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.3.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgatos SD, Pyrpasopoulou A, Theodoropoulos PA. Nuclear envelope breakdown in mammalian cells involves stepwise lamina disassembly and microtubule-driven deformation of the nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2129–2140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.17.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins JR, Tilney LG, Porter KR. Microtubules in the formation and development of the primary mesenchyme in Arbacia punctulata. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:201–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groigno L, Whitaker M. An anaphase calcium signal controls chromosome disjunction in early sea urchin embryos. Cell. 1998;92:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80914-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi Y, Satoh SK, Hamaguchi MS. Projections of the nuclear envelope into the nucleus prior to its breakdown. Bioimages. 1993;1:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. The role of membranes in the organization of the mitotic apparatus. Exp Cell Res. 1975;94:409–425. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R, Cubitt AB, Tsien RY. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–664. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson JH, Begg DA, Beaulieu SM, Fishkind DJ, Bonder EM, Terasaki M, Kaminer B. A calsequestrin-like protein in the endoplasmic reticulum of the sea urchin: localization and dynamics in the egg and first cell cycle embryo. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:149–161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Wolniak SM. Membranes in the mitotic apparatus: their structure and function. Int Rev Cytol. 1984;90:169–238. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller G, Weber K. Golgi detection in mitotic and interphase cells by antibodies to secreted galactosyltransferase. Exp Cell Res. 1982;142:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(82)90412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramoto Y. Microinjection of live spermatozoa into sea urchin eggs. Exp Cell Res. 1962;27:416–426. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(62)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg K, Miller CM, Ellenberg J, Presley JF, Siggia ED, Phair RD, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Kinetic analysis of secretory protein traffic and characterization of Golgi to plasma membrane transport intermediates in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1485–1503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstadius S. Experimental Embryology of Echinoderms. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu VW, Shah N, Klausner RD. A brefeldin A-like phenotype is induced by the overexpression of a human ERD-2-like protein, ELP-1. Cell. 1992;69:625–635. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Dan K, Goodenough D. Ultrastructure and 3H-thymidine incorporation by chromosome vesicles in sea urchin embryos. Chromosoma. 1981;83:441–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00328271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesch SA, Linstedt AD. The Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum remain independent during mitosis in HeLa cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:623–635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehart D. Microinjection of echinoderm eggs: apparatus and procedures. Methods Cell Biol. 1982;25:13–31. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage T, Gache C. Purification and characterization of the sea urchin embryo hatching enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4787–4793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage T, Gache C. Early expression of a collagenase-like hatching enzyme gene in the sea urchin embryo. EMBO J. 1990;9:3003–3012. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage T, Sardet C, Gache C. Spatial expression of the hatching-enzyme gene in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 1992;150:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz J, Cole NB, Donaldson JG. Building a secretory apparatus: role of ARF1/COPI in Golgi biogenesis and maintenance. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;109:449–562. doi: 10.1007/s004180050247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yuan LC, Bonifacino JS, Klausner RD. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell. 1989;56:801–813. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90685-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish H, Baltimore D, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Darnell J. Molecular Cell Biology. 3rd ed. New York: Scientific American Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe M, Nakamura N, Warren G. Golgi division and membrane traffic. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:40–44. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero HA, Lebeche D, Kaminer B. ER calcistorin/protein disulfide isomerase (PDI): sequence determination and expression of a cDNA clone encoding a calcium storage protein with PDI activity from endoplasmic reticulum of the sea urchin egg. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23112–23119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M. Species specific pattern of ciliogenesis in developing sea urchin embryos. Dev Growth Differ. 1979;21:545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1979.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T, Warren G. Mitotic disassembly of the Golgi apparatus in vivo. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2715–2727. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.7.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Pelham HR. A C-terminal signal prevents secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell. 1987;48:899–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A, Hunt T. The Cell Cycle. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Presley JF, Cole NB, Schroer TA, Hirschberg K, Zaal KJ, Lippincott-Schwartz J. ER-to-Golgi transport visualized in living cells. Nature. 1997;389:81–85. doi: 10.1038/38001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presley JF, Smith C, Hirschberg K, Miller C, Cole NB, Zaal KJM, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Golgi membrane dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1617–1626. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SF, Sha'afi RI, Berlin RD. Regulation of Ca2+ influx during mitosis: Ca2+ influx and depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores are coupled in interphase but not mitosis. Cell Regul. 1991;2:915–925. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.11.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier JC, Kafatos FC. Absolute rates of protein synthesis in sea urchins with specific activity measurements of radioactive leucine and leucyl-tRNA. Dev Biol. 1977;57:270–283. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe JL, Lennarz WJ. Biosynthesis and secretion of the hatching enzyme during sea urchin embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8704–8711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza JC, Hardwick KG, Dean N, Pelham HR. ERD2, a yeast gene required for the receptor-mediated retrieval of luminal ER proteins from the secretory pathway. Cell. 1990;61:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90698-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima DT, Cabrera-Poch N, Pepperkok R, Warren G. An ordered inheritance strategy for the Golgi apparatus: visualization of mitotic disassembly reveals a role for the mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:955–966. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima DT, Haldar K, Pepperkok R, Watson R, Warren G. Partitioning of the Golgi apparatus during mitosis in living HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1211–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias DA, Wright BD, Wedamen KP, Cole DG, Buster D, Scholey JM. Analysis of kinesin-driven membrane transport in dividing sea urchin blastomeres. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:391a. [Google Scholar]

- Sluder G, Miller FJ, Spanjian K. The role of spindle microtubules in the timing of the cell cycle in echinoderm eggs. J Exp Zool. 1986;238:325–336. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley H, Botas J, Malhotra V. The mechanism of Golgi segregation during mitosis is cell type-specific. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14467–14470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storrie B, White J, Rottger S, Stelzer EHK, Suganuma T, Nilsson T. Recycling of Golgi-resident glycosyltransferases through the ER reveals a novel pathway and provides an explanation for nocodazole-induced Golgi scattering. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1505–1521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers RG, Morrill JB, Leith A, Marko M, Piston DW, Stonebraker AT. A stereometric analysis of karyokinesis, cytokinesis and cell arrangements during and following fourth cleavage period in the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. Dev Growth Differ. 1993;35:41–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1993.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JA, McNeil PL. Nuclear reassembly excludes large macromolecules. Science. 1987;238:548–550. doi: 10.1126/science.2443981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M. Redistribution of cytoplasmic components during germinal vesicle breakdown in starfish oocytes. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1797–1805. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Chen LB, Fujiwara K. Microtubules and the endoplasmic reticulum are highly interdependent structures. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1557–1568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Jaffe LA. Organization of the sea urchin egg endoplasmic reticulum and its reorganization at fertilization. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaki M, Jaffe LA, Hunnicutt GR, Hammer JA., III Structural change of the endoplasmic reticulum during fertilization: evidence for loss of membrane continuity using the green fluorescent protein. Dev Biol. 1996;179:320–328. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyberg J, Moskalewski S. Reorganization of the Golgi complex in association with mitosis: redistribution of mannosidase II to the endoplasmic reticulum and effects of brefeldin A. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1992;24:495–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsley FM, Wilson DW, Pelham HR. Mutational analysis of the human KDEL receptor: distinct structural requirements for Golgi retention, ligand binding and retrograde transport. EMBO J. 1993;12:2821–2829. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G. Membrane partitioning during cell division. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:323–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G, Levine TP, Misteli T. Mitotic disassembly of the mammalian Golgi apparatus. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:413–415. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G, Wickner W. Organelle inheritance. Cell. 1996;84:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooding S, Pelham HRB. The dynamics of Golgi protein traffic visualized in living yeast cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2667–2680. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Guan T, Gerace L. Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope are dispersed throughout the endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1199–1210. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaal KJM, et al. Golgi membranes are absorbed into and re-emerge from the ER during mitosis. Cell. 1999;99:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeligs JD, Wollman SH. Mitosis in rat thyroid epithelial cells in vivo. I. Ultrastructural changes in cytoplasmic organelles during the mitotic cycle. J Ultrastruct Res. 1979;66:53–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]