Abstract

Cytosolic chaperonin containing t-complex polypeptide 1 (CCT)/TRiC is a group II chaperonin that assists in the folding of newly synthesized proteins. It is a eukaryotic homologue of the bacterial group I chaperonin GroEL. In contrast to the well studied functions of GroEL, the substrate recognition mechanism of CCT/TRiC is poorly understood. Here, we established a system for analyzing CCT/TRiC functions by using a reconstituted protein synthesis by using recombinant elements system and show that CCT/TRiC strongly recognizes WD40 proteins particularly at hydrophobic β-strands. Using the G protein β subunit (Gβ), a WD40 protein that is very rich in β-sheets, as a model substrate, we found that CCT/TRiC prevents aggregation and assists in folding of Gβ, whereas GroEL does not. Gβ has a seven-bladed β-propeller structure; each blade is formed from a WD40 repeat sequence encoding four β-strands. Detailed mutational analysis of Gβ indicated that CCT/TRiC, but not GroEL, preferentially recognizes hydrophobic residues aligned on surfaces of β-strands in the second WD40 repeat of Gβ. These findings indicate that one of the CCT/TRiC-specific targets is hydrophobic β-strands, which are highly prone to aggregation.

Keywords: molecular chaperone, protein aggregation, protein folding, substrate recognition, WD40 repeat

Molecular chaperones play crucial roles in the folding of newly synthesized proteins and the refolding of denatured proteins (1, 2). Chaperonins are a group of molecular chaperones that form a double-ring-like oligomeric structure composed of 60-kDa subunits and assist in the folding of proteins in the presence of ATP (3–5). The function of group I chaperonins has been well studied by using GroEL, which has a homooligomeric structure with 7-fold rotational symmetry and assists protein folding by cooperating with cochaperonins like GroES (6–9). GroEL recognizes nonnative proteins, particularly those displaying hydrophobic surfaces, in relatively unstructured (10) to partially folded (3, 5) states. Recently, (βα)8 TIM-barrel domain proteins were shown to be substrate proteins frequently recognized by GroEL (11), indicating that GroEL recognizes a particular range of proteins as substrates. In contrast, however, the functions of the group II chaperonins still are largely unknown.

Chaperonin containing t-complex polypeptide 1 (CCT) (also called TRiC) is a group II chaperonin that assists in protein folding in the eukaryotic cytosol (12–14). It forms a double-ring-like hexadecamer complex consisting of eight different subunit species. CCT assists in the folding of actin, tubulin, von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppresser, and several other proteins (15–19). Although CCT appears to recognize a particular substrate structure (13, 20, 21) that is distinct from GroEL substrates, little is known regarding common substrate structures recognized by CCT.

Recently, five WD40 family proteins were shown to transiently associate with CCT after de novo synthesis in yeast (22). WD40 repeat proteins contain four or more copies of an ≈40-aa stretch that typically ends in Trp-Asp (WD); they have β-propeller structures composed of β-sheets and are involved in a wide variety of crucial biological functions (23). One of the WD40 proteins recognized by CCT was the yeast homologue of heterotrimeric G protein β subunit (Gβ), an essential component of G protein (24). Knockdown of the CCTα subunit in HEK293 cells by RNA interference down-regulates Gβγ (25). Thus, CCT appears to be required for folding Gβ and/or for its assembly with Gγ. However, the mechanism by which CCT acts as a chaperone for Gβ is poorly understood. Moreover, it is not known yet how CCT and Gβ interact.

Here, we established an in vitro system to evaluate CCT functions for newly synthesized proteins by using the protein synthesis using recombinant elements (PURE) system; this system is an in vitro transcription/translation system composed only of purified proteins that are essential for transcription, translation, and energy regeneration (26). Using the PURE system to eliminate the effects of other contaminating chaperones, we identified distinct functions of CCT in the productive folding of Gβ and the motif specifically recognized by CCT.

Results

CCT Assists Folding of β-Actin Translated in the PURE System.

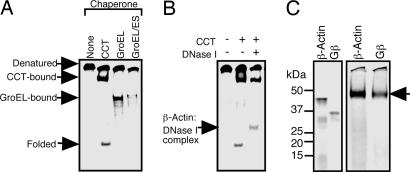

CCT assists in the folding of a range of newly synthesized proteins (≈10% of total cellular proteins). Although CCT has been suggested to have a distinct substrate specificity, little is known regarding the fundamental rules for CCT-dependent substrate recognition. We first tested whether proteins translated in the PURE system are efficiently recognized and folded by CCT with β-actin as a model substrate. β-Actin translated in this system in the presence or absence of CCT was subjected to native PAGE (Fig. 1A). CCT-bound β-actin and folded β-actin were detected, in addition to unfolded polypeptide, which is consistent with previous observations with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (16). Escherichia coli GroEL also bound newly translated actin but could not fold it even in the presence of its cochaperonin GroES (Fig. 1A), which also is consistent with previous observations (15). The conformation of the CCT-folded β-actin was confirmed by testing its ability to bind to DNase I, because only properly folded actin can bind to DNase I (16). A clear shift in mobility of the folded β-actin band in native PAGE was observed only in the presence of CCT and DNase I (Fig. 1B), indicating that β-actin translated in the PURE system was folded by CCT into a functional conformation.

Fig. 1.

CCT-assisted folding of newly synthesized human β-actin in the PURE system and CCT recognition of Gβ. (A) In vitro translation in the presence of [35S]Met was carried out with or without CCT, GroEL, or GroEL/ES. Radiolabeled products were analyzed by native PAGE with 4.5% gels. (B) After translation of β-actin, DNase I was added. β-Actin–DNase I complex was detected by native PAGE. (C) β-Actin and Gβ translated in the presence of CCT were analyzed by SDS/PAGE (Left) and native PAGE (Right).

Roles of CCT in Preventing Aggregation of Newly Translated Gβ and Assisting in Gβ Folding.

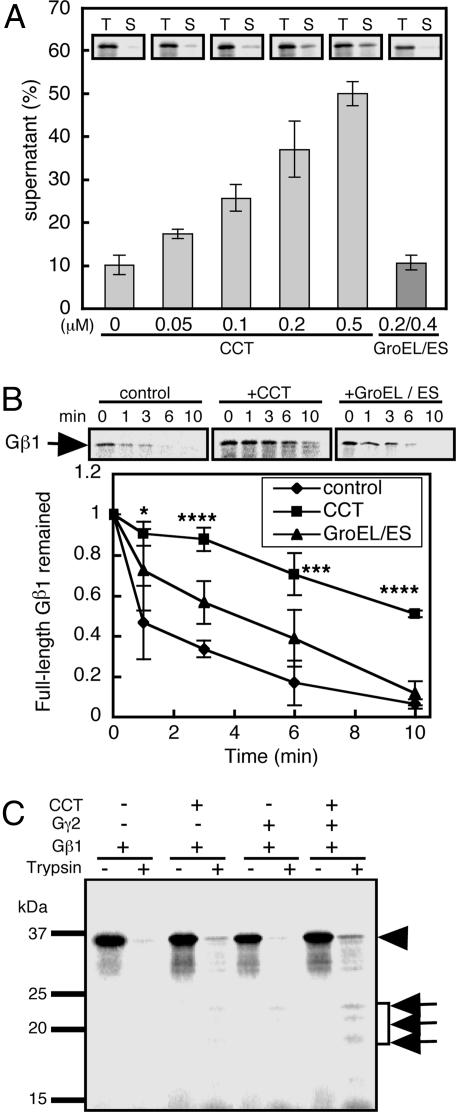

We next examined the binding of CCT to various newly synthesized proteins. These proteins included two α/β fold proteins that are known to be recognized by CCT (human β-actin and β-tubulin), five WD40 repeat proteins that are mostly composed of β-sheets [human Gβ1, Caenorhabditis elegans actin-interacting protein-1 (AIP-1), human AIP-1 homolog WD40 repeat protein 1 (WDR1), S. cerevisiae Cdc20, and the human homologue of Cdc20], and four proteins that lack β-strands (human α-globin, β-globin, Gγ1 and Gγ2) (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Intriguingly, proteins containing β-strands, but not those lacking β-strands, were strongly recognized by CCT. We selected Gβ, which displayed strong CCT binding activity comparable to β-actin (Fig. 1C), as a β-strand rich model protein to analyze CCT–substrate interactions in detail. The Gβ synthesis rate in the PURE system was not affected by the presence of CCT, and the formation of a CCT–Gβ complex was saturated by ≈60 min (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The binding of Gβ to CCT also was detected by sucrose gradient density centrifugation (Fig. 10A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Under these conditions, the percentage of Gβ in the soluble fraction increased in a dose-dependent manner to 50% from 10%, upon the addition of CCT (Fig. 2A). In contrast, GroEL/GroES had no significant effect on Gβ solubility. Thus, CCT prevents Gβ from aggregation in a CCT-specific manner.

Fig. 2.

Newly translated Gβ is protected from aggregation by CCT but not by GroEL. (A) CCT prevents Gβ aggregation. Gβ was translated in the presence or absence of CCT or GroEL/GroES. Gβ in the total synthesized fraction (T) and in the supernatant after centrifugation (S) was analyzed by SDS/PAGE, and the percentage in the supernatant fraction was determined (n = 3). (B) CCT protects Gβ from tryptic digestion. Gβ in soluble fractions was digested with l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin for the indicated periods (Upper), and the radioactivity of the Gβ bands was determined (n = 3) (Lower). (C) CCT-assisted folding of Gβ in the presence of Gγ2. Gβ, and Gγ2 were translated in the presence and absence of 35S-Met, respectively. These samples were mixed and then subjected to tryptic digestion. The full-length and trypsin-resistant portions of Gβ are indicated by the arrowhead and arrows, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences (see Materials and Methods).

CCT also significantly enhanced the protease resistance of Gβ (Fig. 2B). The acquisition of protease resistance by Gβ suggests either that Gβ was protected by being trapped in the CCT cylinder, or that Gβ was folded into a protease-resistant conformation with the assistance of CCT. Intriguingly, GroEL/GroES did not significantly enhance the protease resistance of Gβ (Fig. 2B), even though GroEL binds strongly to Gβ (Fig. 10B). We further examined the folding of Gβ in the presence of Gγ, because Gβ is unable to adopt a compact functional structure in the absence of Gγ (27). Trypsin-resistant bands of Gβ were detected at 20–25 kDa and at the full-length 37-kDa protein (Fig. 2C), which is consistent with previous observations with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (27). These results suggest that the folding state of Gβ is improved in the presence of CCT.

Thus, CCT can prevent aggregation of newly synthesized Gβ, probably by assisting in its folding, at least in part. Moreover, it is clear that CCT acts differently from GroEL/GroES in these functions.

The WD2 Repeat of Gβ Is Strongly Recognized by CCT but Not by GroEL.

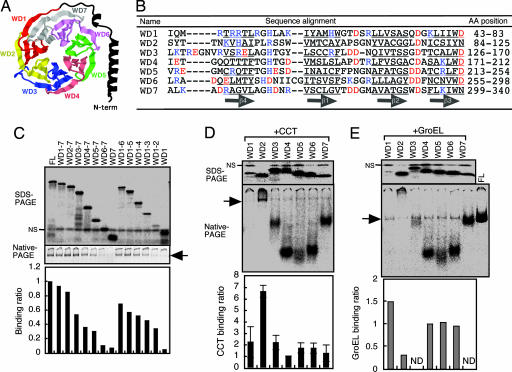

Gβ is made up of two structurally distinct regions: a short N-terminal α-helix domain (amino acid positions 1–42) and the WD40 repeat domain (amino acid positions 43–340) containing seven blades of β-propeller structure. The WD40 repeats are numbered WD1–WD7 from the N- to the C terminus (Fig. 3A and B; ref. 28), respectively. To determine which region(s) of Gβ bind to CCT, we translated a series of Gβ fragments, in the presence of CCT, in which increasing numbers of the WD40 repeats were serially deleted from the N terminus to C terminus or vice versa (Fig. 11A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The translated deletion mutants were detected as single major bands on SDS/PAGE and subjected to native PAGE (Fig. 3C). The radioactivity of each CCT-bound Gβ mutant was normalized against that of the total soluble Gβ mutant. We found that CCT binding to the Gβ fragments gradually was reduced as the number of WD40 repeats decreased, regardless of the direction of deletion. However, a particularly large reduction was observed when WD2 was deleted.

Fig. 3.

The WD2 repeat of Gβ is strongly and specifically recognized by CCT but not by GroEL. (A) Schematic representation of human Gβ1 structure. This model is based on the β-propeller-containing crystal structure of bovine Gβ1. Each of the seven WD40 repeats (WD1–WD7) contains four-stranded β-sheets. (B) Sequence alignment of the seven WD40 repeats of the human Gβ1. Amino acid residues constituting β-strand structures are underlined. Negatively and positively charged residues are shown in red and blue, respectively. (C) CCT binding to Gβ deletion mutants. Gβ deletion mutants were translated in the presence of CCT, and soluble fractions were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and native PAGE. (D) CCT binding to individual WD40 repeats of Gβ (n = 3). (E) GroEL binding to individual WD40 repeats of Gβ. NS, nonspecific bands. Arrows indicate CCT-bound or GroEL-bound products. ND, not determined.

To analyze the CCT-binding activity of each WD40 repeat of Gβ, single repeats (WD1–WD7) were translated and analyzed for CCT binding by native PAGE (Fig. 3D). CCT was found to bind WD2 much more strongly than the other WD40 repeats. In contrast to CCT, GroEL bound only very weakly to WD2 relative to the other single repeats (Fig. 3E). Comparison of these data indicated that WD2 has a significantly higher CCT-specific binding activity than the other repeats (Fig. 11B).

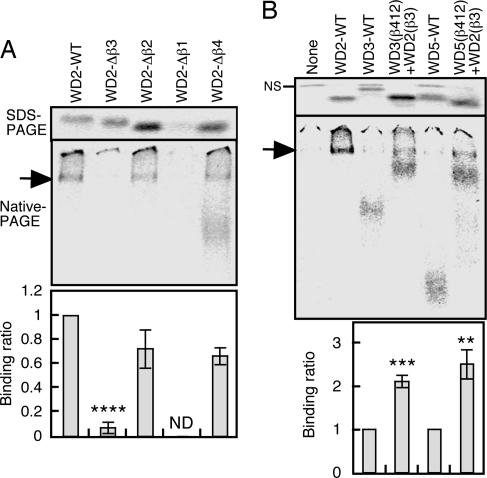

The β-Strand 3 Region of WD2 Plays a Crucial Role in CCT Recognition.

WD2 is a 42-aa polypeptide that generates four β-strands in the crystal structure of Gβ (Fig. 3A and B). These β-strands have been numbered β4, β1, β2, and β3 (from the N to the C terminus) (28). To determine which segment(s) are responsible for CCT-specific binding, WD2 mutants that lack one of these β-strands (Fig. 12A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) were translated and analyzed for CCT-binding activity (Fig. 4A). After elimination of β3, WD2 lost 90% of its CCT-binding activity, indicating that β3 is required for recognition by CCT.

Fig. 4.

The β3 region of WD2 is strongly recognized by CCT. (A) The deletion of β3 diminishes the binding of WD2 to CCT. WD2 and its deletion mutants shown in Fig. 12A were translated in the presence of CCT, and the soluble fractions were subjected to tricine-SDS/PAGE and native PAGE. CCT-binding ratios are shown at the bottom (n = 3). (B) The β3 region of WD2 significantly enhances CCT binding affinity of other WD40 repeats. The β3 region of WD3 or WD5 was replaced by the β3 of WD2, as shown in Fig. 12B, and CCT-binding ratios were determined (n = 3). NS, nonspecific bands. ND, not determined.

To further analyze recognition of β3, the β3 regions of WD3 and WD5, which bound only very weakly to CCT (Fig. 3D), were replaced by the β3 region of WD2 (Fig. 12B), and CCT binding was compared with that of the original WD3 and WD5 (Fig. 4B). The CCT-binding ratios were significantly increased by substituting the WD2 β3 region. Taken together with the deletion experiments described above, these data indicate that the WD2 β3 region is most strongly recognized by CCT.

Amino Acid Residues Involved in CCT Binding.

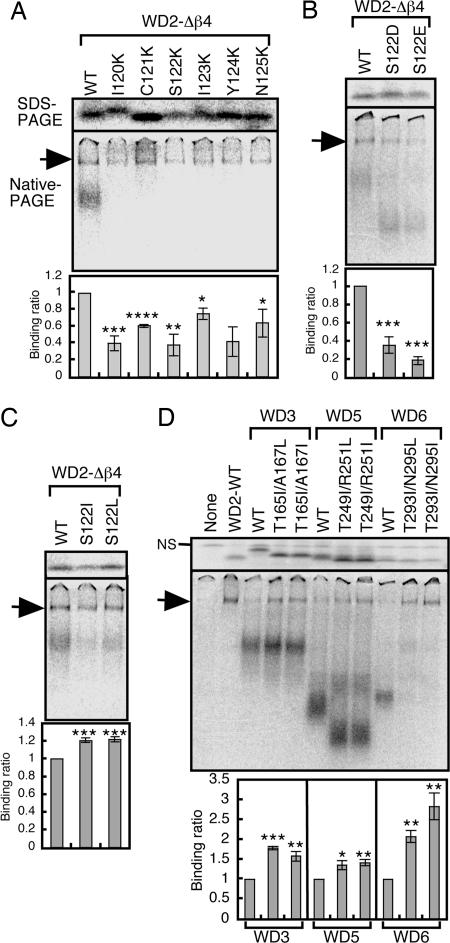

Because the β3 region of WD2 lacks charged residues, whereas those of the other WD40 repeats do not (Fig. 3B), we examined the effect of charged residues in CCT binding by introducing lysine in the β3 sequence of WD2; we deleted the β4 region because it makes a relatively small contribution to CCT binding (Fig. 4A) and is located in a β-propeller different from that of β1–β3 in the Gβ crystal structure (Fig. 3A). Each of the lysine mutations reduced CCT recognition of WD2-Δβ4 (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the interaction between WD2-Δβ4 and CCT is not an electrostatic one. Consistent with this hypothesis, replacement of S122 with negatively charged residues also strongly reduced the CCT-binding activity of WD2-Δβ4 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

CCT recognizes the φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequences in the β3 region of WD40 repeats, where φ is a hydrophobic residue. (A) Single amino acids in the β3 region of WD2-Δβ4 were substituted with lysine, and these mutants were analyzed for CCT binding (n = 3). (B and C) The S122 residue of WD2-Δβ4 was substituted with negatively charged (B) or hydrophobic (C) residues (n = 3). (D) Converting WD3, WD5, or WD6 to φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequence-containing WD40 repeats significantly enhances their binding to CCT (n = 3).

The residues in the β3 region of WD2 can be classified into three categories: nonpolar hydrophobic residues (I120 and I123), polar residues with small side chains (C121 and S122), and polar residues with large side chains (Y124 and N125), suggesting that CCT recognizes the β3 region of WD2 either by hydrophobic or polar interactions. To distinguish these interactions, we replaced S122, which has both hydrophobic and polar properties, with nonpolar hydrophobic residues. These substitutions enhanced WD2 binding to CCT at statistically significant levels although the degree of enhancement was relatively small (Fig. 5C). Intriguingly, lysine substitution of β3 (Fig. 5A) indicated that the three residues that most strongly contribute to CCT binding (I120, S122, and Y124) are separated from each other by single residues that exert relatively mild effects on binding activity (C121, I123, and N125). We therefore tested whether φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequences (where φ is a hydrophobic residue) introduced into β3 regions of other WD40 repeats are recognized by CCT. When a φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequence was generated in the β3 region of WD3, WD5, or WD6 by replacing residues to leucine or isoleucine at the φ positions, CCT-binding activity was significantly enhanced in all cases (Fig. 5D). Thus, the φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequence in β3 is preferentially recognized by CCT, even when located in different WD40 repeats.

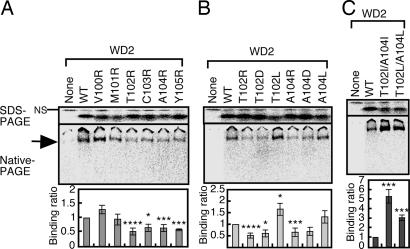

CCT Also Recognizes the β-Strand 1 of WD2 by Hydrophobic Interactions.

Because we were unable to examine CCT binding to the β1 region of WD2 by deletion because of the absence of translated products (Fig. 4A), we tested binding by amino acid substitutions with positively charged arginine in β1 (Fig. 6A). Replacement of any single residue from T102 to Y105 significantly reduced CCT binding to WD2, whereas replacement of V100 and M101 had no effect. Substitutions to negatively charged residues (T102D and A104D) also inhibited the binding (Fig. 6B). In contrast, substituting hydrophobic residues (T102L) significantly enhanced binding activity. The enhancement of binding was much stronger when φ-x-φ-x sequence was produced by double substitution to more hydrophobic residues (T102I/A104I or T102L/A104L) (Fig. 6C). Because the effect of substituting hydrophobic residues is stronger for β1 than for β3, the CCT binding appears to be weaker to the original β1 than to β3. The weaker binding may be due to inaccessibility to V100 and M101, which are oriented differently from the other four residues (Fig. 7B; see also Fig. 13, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 6.

CCT recognizes the β1 of WD2 through hydrophobic interactions. The indicated single (A and B) or double (C) mutations were introduced into WD2 and analyzed for CCT binding (n = 3).

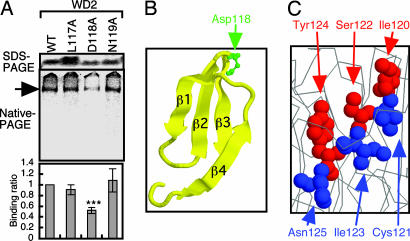

Fig. 7.

WD2 secondary structure is likely to be required for CCT recognition. (A) Single amino acid substitutions were introduced into the loop bridging the β2 and β3 regions of WD2, and these mutants were analyzed for CCT binding (n = 3). (B) The position of the D118 residue that stabilizes the β-sheet structure of WD2. (C) Location of the residues that form the β3 of WD2 in the molecular structure of Gβ. The φ and x residues of the φ-x-φ-x-φ-x (I120 to N125) sequence in the β3 region of WD2 are indicated by the red and blue space-filled models, respectively.

Possible Contribution of WD2 Secondary Structure to CCT Recognition.

CCT has been suggested to recognize quasi-native or partially folded intermediates of substrate proteins (20). To investigate the relevance of the φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequences recognized by CCT, these residues were plotted onto the crystal structure of Gβ (28). The strongly contributing residues (I120, S122, and Y124) were clearly aligned on the same surface of β3 in WD2, whereas the weakly contributing residues were found on the opposite side of the β-strand (Fig. 7C). The residues on β1 contributing to the binding to CCT also were found in a small surface of the β-strand (Fig. 13). These observations suggest that the secondary structure of WD2 was recognized by CCT. To test this hypothesis, the D118 residue in WD2 (Fig. 7B) was substituted with alanine, because D118 is required to stabilize the β-sheet structure of WD40 repeats (27). The D118A mutation was found to markedly reduce CCT binding to WD2, whereas single mutations of its neighboring residues (L117A or N119A) had no significant effect (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, Gβ was recognized by CCT even 30 min after termination of translation (Fig. 14, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), a time by which newly synthesized proteins are thought to have spontaneously adopted secondary structures. We thus propose that CCT can recognize hydrophobic residues exposed on certain β-sheet structures, including the anti-parallel β-sheet of WD40 repeats.

Discussion

In the present study, we used the PURE system to analyze CCT-dependent folding and substrate recognition mechanisms. The advantage of this system is that it is free of chaperones, unlike other cell-free systems, and requires the use of only a few micrograms of purified CCT (Fig. 1). We tested a panel of substrates and showed that CCT preferentially binds to proteins containing β-strands when newly translated. This result is consistent with the previous observations that α-globin and β-globin, which lack β-strand structures, showed no significant binding to CCT when translated in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (29). The strong binding of CCT to WD40 proteins in vitro, which we showed in the present study, is consistent with previous studies in yeast that revealed CCT binding to WD40 repeat proteins in vivo (22, 30). Of the WD40 proteins tested, Gβ was most strongly recognized by CCT. Using this protein as a model substrate, we found that CCT prevents aggregation of newly translated Gβ aggregation (Fig. 2). This evidence reveals that CCT efficiently prevents aggregation of newly synthesized WD40 proteins. Moreover, Gβ translated in the presence of CCT was protected from protease digestion, and protease-resistant fragments of Gβ were detected when CCT and Gγ both were present. Thus, CCT is likely to facilitate Gβ folding, in addition to protecting it through its binding in the central cavity of CCT. This model is consistent with a recent study showing that RNA interference knockdown of the CCTα subunit in HEK293 cells down-regulates Gβγ (25). Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that one of the functions of CCT is to facilitate the effective production of correctly folded β-strand-rich proteins by preventing aggregation of β-strands or β-sheets. This function is likely to be particularly important for hydrophobic β-sheets because they are highly aggregation-prone structures (31). Interestingly, an RNA interference screening for genes protecting C. elegans from polyglutamine aggregation indicated that CCT subunit genes are required for effective prevention of polyglutamine aggregation (32), which supports the hypothesis that CCT is a chaperone for β-sheets because polyglutamines are believed to be aggregated into β-sheet structures (33).

Unlike CCT, GroEL/GroES could not protect Gβ from aggregation or protease digestion, despite the fact that GroEL binds strongly to Gβ. Thus, CCT possesses a chaperone function distinct from that of GroEL/GroES. GroEL has been shown to recognize nonnative substrates in relatively unstructured (10) to partially folded (3, 5) states, whereas CCT was suggested to recognize preferably quasi-native or partially folded intermediates of substrate proteins (13, 20, 21). Many nonnative proteins are recognized by GroEL, and a comprehensive study of GroEL substrates has indicated that GroEL prefers the nonnative states of proteins that contain two or more αβ-domains (34). Furthermore, a more recent study demonstrated that (βα)8 TIM-barrel domain proteins are frequently found as GroEL substrates (11). These observations therefore suggest that CCT and GroEL recognize different fold structures, at least in part.

However, two WD40 repeat proteins are known to exhibit no significant interaction with CCT: yeast Cdc4 and Bub3 (22, 30). These observations suggest that CCT recognizes a particular range of β-strand-containing proteins. In the present study, the WD2 of Gβ was found to play a crucial role in CCT binding (Fig. 3). In particular, hydrophobic residues in the β3 region are indispensable for CCT recognition (Figs. 4 and 5). Thus, it appears that CCT preferably recognizes hydrophobic β-strands in WD40 repeats. Consistent with these data, Feldman et al. (19) reported that CCT recognizes two hydrophobic β-strands in von Hippel-Lindau. In the case of von Hippel-Lindau, however, mutants defective in CCT binding did not form aggregates in vivo or in vitro, in contrast to our observations with Gβ.

Intriguingly, the φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequence in the β3 region of WD2 was important for CCT binding. The positive effect of φ-x-φ-x-φ-x sequences on CCT binding was common to other WD40 repeats, because CCT binding activity was significantly enhanced when these sequences were introduced into WD3, WD5, and WD6. The localization of the φ residues to the same surface of the WD2 β3 suggests that the structure of β3 plays a role in recognition by CCT (Fig. 7). In addition, the WD2 β1 also was recognized by CCT through hydrophobic interactions, although its binding to CCT may be weaker than β3 binding to CCT. Moreover, CCT binding to WD2 was reduced significantly by mutating the D118 residue, which stabilizes the β-sheet structure (27). In the von Hippel-Lindau structure, the residues on the two β-sheets recognized by CCT also were localized in the same orientation (19). Thus, hydrophobic residues aligned on the same surface of β-strands are likely to be preferentially recognized by CCT, and the existence of multiple binding sites in the substrate appears to enhance its CCT-binding activity. Based on the thermosome crystal structure, CCT has no obvious hydrophobic patch for substrate binding (35). Small hydrophobic regions in different CCT subunits may interact with the small hydrophobic surfaces of multiple β-strands, although this possibility remains to be investigated.

In conclusion, these observations indicate that hydrophobic β-strands are a target structure in substrates recognized by CCT, particularly when located in β-sheets, as in the case of WD40 repeat proteins. We propose that CCT prevents the aggregation of hydrophobic β-sheets to facilitate correct folding of nascent proteins.

Materials and Methods

Chaperonin Purification.

CCT was purified from bovine testis, as described in ref. 36, with the following modifications. The DE52 cellulose column and 10/10MonoQ column were replaced by the Toyopearl DEAE-650M (Tosoh, Tokyo) and the Source 30Q (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences), respectively. After glycerol was added to a final concentration of 20%, CCT was stored at −80°C until analysis. GroEL and GroES were purified from E. coli overexpressing these proteins, as described in ref. 37.

In Vitro Translation in the PURE System Supplemented with Chaperonin.

Human β-actin cDNA was described in ref. 38, Gβ1 cDNA was cloned by a PCR-mediated method, and nucleotide sequence was confirmed by sequencing. Transcription/translation of target proteins was performed with the PURE system by using the Classic or Classic II kit (Post Genome Institute, Tokyo). The template DNAs were generated by two-step PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The first-step PCR amplified ORFs, and the second-step PCR generated the T7 promoter sequence by using the primers shown in Tables 1–6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. In vitro transcription/translation was started by adding the second-step PCR products to the PURE system reaction mixture (15 μl unless otherwise indicated) in the presence of 7.4 kbq/μl 35S-Met at 37°C, and this initiation of reaction was followed by a 30-min incubation for chaperonin binding and protease sensitivity assays or a 60-min incubation for other experiments. To analyze chaperonin function, the translation reaction was performed in the presence of 0.2 μM CCT or 0.2 μM GroEL/0.4 μM GroES unless otherwise indicated.

β-Actin Folding Assay.

Human β-actin was translated in the PURE system (20 μl), supplemented with 35S-Met in the presence of CCT or GroEL/GroES. Translated products were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was recovered. After incubation with 50 μg/ml RNase A at 37°C for 30 min, a 1/5 volume of 5× native PAGE sample buffer (80% glycerol/80 mM Mops/KOH, pH 7.2/0.2% bromophenol blue) was added. Samples were subjected to native PAGE in the presence of MgCl2 and ATP (39) by using 4.5% gels. Half of the sample was treated with 50 μg/ml DNase I if required. Radiolabeled β-actin was visualized by using a STORM 820 image analyzer (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences).

Chaperonin-Binding Assay.

Substrate proteins were translated in the PURE system in the presence of CCT or GroEL. Translation and the chaperonin cycle were stopped by adding RNaseA (50 μg/ml) and a 1/5 volume of 5× stop buffer (100 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.5/50 mM CDTA/1 mM CaCl2) and incubating at 37°C for 5 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. After adding native PAGE sample buffer, the supernatants were subjected to native PAGE in the absence of MgCl2 and ATP by using 4.5% gels.

Gβ Solubility Test.

Gβ was translated in the PURE system in the presence of CCT (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μM) or GroEL/GroES. RNase A (50 μg/ml) and stop buffer-treated solutions were subjected to centrifugation (20,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min). Samples of the total translation mixture and the supernatant fraction were analyzed by SDS/PAGE with 12% gels.

Protease Sensitivity Assay.

Gβ was translated in the PURE system in the presence of CCT or GroEL/GroES. After treatment with RNase A and stop buffer, soluble fractions were recovered by centrifugation (20,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min). Tryptic digestion was initiated by adding 1 μl of 50 μg/ml l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin (Sigma) to 22 μl of supernatant. After incubation at 30°C for appropriate period, the reaction was stopped by adding 20 mM PMSF and SDS/PAGE sample buffer followed by heat treatment at 100°C for 5 min. The Gβ remained was detected by SDS/PAGE with 12% gels.

CCT-Assisted Gβ Folding in the Presence of Gγ.

Gβ and Gγ2 were separately translated in the PURE system, supplemented with CCT (0.56 μM) in the presence and absence of 35S-Met, respectively. After adding a 1/10 volume of 1 mg/ml RNaseA followed by an incubation for 5 min at 37°C, these reaction mixtures were combined at a 6:5 (Gβ/Gγ2) volume ratio and further incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Tryptic digestion was carried out in 6.2-μl samples in the presence of 10 pmol l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin at 37°C for 5 min, and trypsin-resistant products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE with 12% gels.

Statistical Analysis.

Significance of difference was analyzed by Student’s t test (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.02; ∗∗∗, P < 0.01; and ∗∗∗∗, P < 0.001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mana Kadota for technical assistance and Drs. Koreaki Ito and Yoshinori Akiyama for providing the pKY206 groELS plasmid.

Abbreviations

- CCT

chaperonin containing t-complex polypeptide 1

- PURE

protein synthesis using recombinant elements.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Bukau B., Horwich A. L. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young J. C., Agashe V. R., Siegers K., Hartl F. U. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feltham J. L., Gierasch L. M. Cell. 2000;100:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saibil H. R., Ranson N. A. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:627–632. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton W. A., Horwich A. L. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2003;36:229–256. doi: 10.1017/s0033583503003883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman J. S., Hohl C. M., Kovalenko O., Kashi Y., Chen S., Braig K., Saibil H. R., Fenton W. A., Horwich A. L. Cell. 1995;83:577–587. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinker A., Pfeifer G., Kerner M. J., Naylor D. J., Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. Cell. 2001;107:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhuri T. K., Farr G. W., Fenton W. A., Rospert S., Horwich A. L. Cell. 2001;107:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taguchi H., Ueno T., Tadakuma H., Yoshida M., Funatsu T. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:861–865. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horst R., Bertelsen E. B., Fiaux J., Wider G., Horwich A. L., Wuthrich K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12748–12753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505642102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerner M. J., Naylor D. J., Ishihama Y., Maier T., Chang H. C., Stines A. P., Georgopoulos C., Frishman D., Hayer-Hartl M., Mann M., Hartl F. U. Cell. 2005;122:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota H. Vitam. Horm. (San Francisco) 2002;65:313–331. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(02)65069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Puertas P., Martin-Benito J., Carrascosa J. L., Willison K. R., Valpuesta J. M. J. Mol. Recognit. 2004;17:85–94. doi: 10.1002/jmr.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiess C., Meyer A. S., Reissmann S., Frydman J. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian G., Vainberg I. E., Tap W. D., Lewis S. A., Cowan N. J. Nature. 1995;375:250–253. doi: 10.1038/375250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frydman J., Hartl F. U. Science. 1996;272:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farr G. W., Scharl E. C., Schumacher R. J., Sondek S., Horwich A. L. Cell. 1997;89:927–937. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer A. S., Gillespie J. R., Walther D., Millet I. S., Doniach S., Frydman J. Cell. 2003;113:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman D. E., Spiess C., Howard D. E., Frydman J. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1213–1224. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian G., Vainberg I. E., Tap W. D., Lewis S. A., Cowan N. J. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:23910–23913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llorca O., Martin-Benito J., Ritco-Vonsovici M., Grantham J., Hynes G. M., Willison K. R., Carrascosa J. L., Valpuesta J. M. EMBO J. 2000;19:5971–5979. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegers K., Bolter B., Schwarz J. P., Bottcher U. M., Guha S., Hartl F. U. EMBO J. 2003;22:5230–5240. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Smith T. F., Gaitatzes C., Saxena K., Neer E. J. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clapham D. E., Neer E. J. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:167–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humrich J., Bermel C., Bunemann M., Harmark L., Frost R., Quitterer U., Lohse M. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20042–20050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu Y., Inoue A., Tomari Y., Suzuki T., Yokogawa T., Nishikawa K., Ueda T. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Higuera I., Gaitatzes C., Smith T. F., Neer E. J. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9041–9049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sondek J., Bohm A., Lambright D. G., Hamm H. E., Sigler P. B. Nature. 1996;379:369–374. doi: 10.1038/379369a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melki R., Batelier G., Soulie S., Williams R. C., Jr Biochemistry. 1997;36:5817–5826. doi: 10.1021/bi962830o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camasses A., Bogdanova A., Shevchenko A., Zachariae W. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:87–100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiti F., Taddei N., Baroni F., Capanni C., Stefani M., Ramponi G., Dobson C. M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:137–143. doi: 10.1038/nsb752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nollen E. A. A., Garcia S. M., van Haaften G., Kim S., Chavez A., Morimoto R. I., Plasterk R. H. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6403–6408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307697101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross C. A., Poirier M. A., Wanker E. E., Amzel M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houry W. A., Frishman D., Eckerskorn C., Lottspeich F., Hartl F. U. Nature. 1999;402:147–154. doi: 10.1038/45977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ditzel L., Lowe J., Stock D., Stetter K. O., Huber H., Huber R., Steinbacher S. Cell. 1998;93:125–138. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreyra R. G., Frydman J. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;140:153–160. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-061-6:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakikawa C., Taguchi H., Makino Y., Yoshida M. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21251–21256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokota S., Yanagi H., Yura T., Kubota H. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:4664–4673. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thulasiraman V., Ferreyra R. G., Frydman J. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;140:169–177. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-061-6:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.