Abstract

This study describes a method of gene delivery to pancreatic islets of adult, living animals by ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction (UTMD). The technique involves incorporation of plasmids into the phospholipid shell of gas-filled microbubbles, which are then infused into rats and destroyed within the pancreatic microcirculation with ultrasound. Specific delivery of genes to islet beta cells by UTMD was achieved by using a plasmid containing a rat insulin 1 promoter (RIP), and reporter gene expression was regulated appropriately by glucose in animals that received a RIP–luciferase plasmid. To demonstrate biological efficacy, we used UTMD to deliver RIP–human insulin and RIP–hexokinase I plasmids to islets of adult rats. Delivery of the former plasmid resulted in clear increases in circulating human C-peptide and decreased blood glucose levels, whereas delivery of the latter plasmid resulted in a clear increase in hexokinase I protein expression in islets, increased insulin levels in blood, and decreased circulating glucose levels. We conclude that UTMD allows relatively noninvasive delivery of genes to pancreatic islets with an efficiency sufficient to modulate beta cell function in adult animals.

Keywords: diabetes, gene therapy, ultrasound

Both major forms of diabetes involve beta cell destruction and dysfunction. Type 1 diabetes, which afflicts ≈1 million patients in the United States (1), is a condition of complete insulin deficiency brought about by autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing islet beta cells. Type 2 diabetes afflicts roughly 20 million Americans (1), and the hyperglycemia associated with this disease develops when insulin secretory capacity can no longer compensate for peripheral insulin resistance. Potential new treatments for both forms of diabetes could be developed if it were possible to deliver genes or other molecular cargo to pancreatic islets to enhance insulin secretion or beta cell survival (2). Viral vectors have been used for efficient gene transfer to pancreatic islets ex vivo (3, 4). However, their utility for targeting pancreatic islets in living animals has proved to be limited. Thus, direct injection of recombinant adenovirus or adeno-associated virus into the pancreas results in variable expression of reporter genes in exocrine cells, with negligible expression in pancreatic islets (5). An alternative approach, jugular vein infusion of a β-galactosidase adenovirus into rats during surgical clamping of the hepatic and portal circulation, resulted in β-galactosidase expression in 70% of islets. Unfortunately, this approach is highly invasive, and it induced an inflammatory response (6). Finally, the use of naked DNA or liposome carriers has the disadvantage of low infection efficiency and the requirement for invasive delivery by direct injection. Direct testing of liposomal vectors has shown no significant success in targeting to islets (7), although the vectors do appear to target insulinoma and adenocarcinoma cells of the pancreas (8, 9).

In light of the complications associated with each of the foregoing methods of islet gene delivery in vivo, we have developed a technique that employs ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction (UTMD) to deliver genes or drugs to specific tissues (10–15). Briefly, genes are incorporated into gas-filled microbubbles, which are then injected intravenously and destroyed within the microvasculature of the target organ by ultrasound. We previously reported the use of UTMD to target reporter genes and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis to rat myocardium (10–13). We now demonstrate safe and successful targeting of reporter genes to pancreatic islets by using the rat insulin 1 promoter (RIP) to achieve a high level of islet and beta cell specificity, as well as regulation of the delivered transgene within the islets by glucose feeding. Moreover, beta cell-specific delivery of the hexokinase I gene by UTMD results in increased insulin secretion. Finally, we demonstrate delivery of the human insulin gene to rats in vivo, with subsequent expression of human insulin and C-peptide, and lowering of blood glucose. Our data show that UTMD delivers transgenes to islet beta cells of adult, living animals at a level sufficient to alter beta cell function, thereby providing a potential means for targeting therapeutic agents to the islets in the setting of diabetes.

Results

To confer islet-specific expression, we delivered RIP-driven reporter plasmid constructs [Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein (DsRed) and luciferase] by UTMD. Rodents have two nonallelic insulin genes (16, 17). The insulin 2 gene is expressed in pancreatic beta cells, thymus, choroid plexus, and yolk sac. The insulin 1 gene is expressed only in pancreatic beta cells and scattered cells in the thymus (18–22). Thus, we used a fragment of the RIP (−412 to +155 relative to the transcription start site) for our vector construction to facilitate gene targeting to beta cells.

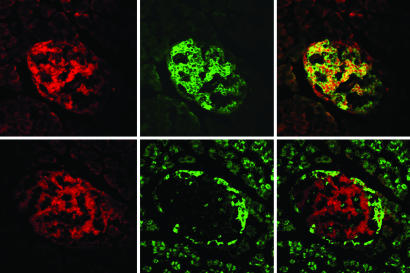

Demonstration of Specific Targeting of DsRed to Islet Beta Cells by Confocal Microscopy.

We first examined whether the expression of DsRed protein was confined to insulin-producing beta cells within the pancreatic islets. Fig. 1 demonstrates expression of the DsRed protein within the central core of islet cells, consistent with the known localization of beta cells within rat islets. The DsRed protein (Upper Left) was identified with a red filter at an excitation wavelength of 568 nm and an emission wavelength of 590–610 nm. Beta cells were identified specifically by immunohistochemical staining with a fluorescence-tagged antibody directed against insulin at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 490–540 nm (Upper Center). Colocalization of the DsRed and insulin signals (Upper Right) confirms that DsRed plasmid expression was present in islet beta cells. The DsRed signal was present only in islet tissue that costained with anti-insulin, indicating a high degree of beta cell specificity. In addition, there were islets identified by insulin staining that did not show DsRed expression. Examination of sections from rats infused with control microbubbles (without plasmid) or control plasmid (LacZ) did not show any detectable DsRed signal (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

High-power confocal image of a section of pancreas treated by UTMD with a DsRed plasmid under the RIP promoter. (Magnification, ×400.) (Upper) Images from the same islet using different filter settings to identify DsRed protein relative to beta cells. (Upper Left) DsRed is present in the islet. (Upper Center) Fluorescent antibody to insulin identifies the beta cells in the islet center through a green filter. (Upper Right) Confocal image confirms colocalization of DsRed and anti-insulin (yellow color) in beta cells. Some DsRed is seen in a nuclear pattern, presumably because it migrates to the nuclear membrane. (Lower) Images from an adjacent slice of the same islet using different filter settings to identify DsRed protein relative to alpha cells. (Lower Left) DsRed is present in the islet. (Lower Center) Fluorescent antibody to glucagon identifies the alpha cells along the islet periphery through a green filter. (Lower Right) A confocal image confirms that DsRed expression does not colocalize with alpha cells.

The location of DsRed expression relative to glucagon-producing alpha cells is also shown in Fig. 1 (Lower). The DsRed protein is shown through a red filter (Lower Left). The alpha cells are identified on the islet periphery by immunohistochemical staining with a fluorescent antibody directed against glucagon (bright green signal; Lower Center). Confocal microscopy (Lower Right) shows that the DsRed signal never colocalizes with the glucagon signal, which remains bright green and located on the islet periphery.

The efficiency of islet transfection was calculated by counting the number of DsRed-positive islets divided by the total number of islets (anti-insulin-positive) and multiplying the ratio by 100. Transfection efficiency was significantly higher for islets treated with the RIP–DsRed compared with the CMV–DsRed plasmid (67 ± 7% vs. 20 ± 5%; F = 235.1, P < 0.0001). As noted above, islets treated with control microbubbles (no plasmid or LacZ plasmid) did not show any detectable transfection.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that coupling of UTMD with plasmids in which transgene expression is controlled by RIP results in efficient delivery of genes in a highly targeted, if not exclusive, fashion to islet beta cells in living rats.

Quantitative Luciferase Gene Expression.

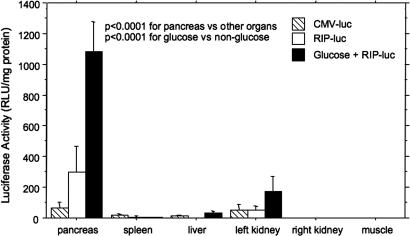

We next quantified gene expression in the pancreas compared with other organs within the ultrasound beam (left kidney, spleen, liver) and outside the ultrasound beam (right kidney, hindlimb skeletal muscle). Rats were killed at day 4 after UTMD, and luciferase activity was measured in each organ and indexed for protein content as relative light units (RLU)/mg of protein. Fig. 2 shows a comparison of luciferase activity in these organs for three groups of rats: animals that received CMV–luciferase microbubbles and were fed normal chow and water; animals that received RIP–luciferase microbubbles and were fed normal chow and water; and animals that received RIP–luciferase microbubbles and were fed normal chow plus water supplemented with 20% wt/vol glucose. Animals were provided these diets for 4 days before they were killed. In animals that received CMV–luciferase, a low level of activity was detected in all organs within the ultrasound beam. No activity was detected in skeletal muscle or right kidney, which lie outside the ultrasound beam. By ANOVA, the difference in pancreatic luciferase activity among organs was statistically significant (F = 42.4, P < 0.0001) because of the markedly higher activity in pancreas compared with the other organs. Of particular importance, the RIP–luciferase plasmid increased pancreatic activity by 100-fold compared with liver (298 ± 168 RLU/mg of protein vs. 2.9 ± 0.8 RLU/mg of protein), indicating that this technique largely circumvents the problem of hepatic uptake seen with viral vectors.

Fig. 2.

Whole-pancreas luciferase activity in rats treated with CMV–luc (hatched bars), RIP–luc (white bars), or RIP–luciferase plus a 20% wt/vol glucose feeding (black bars) for 4 days after UTMD. Glucose feeding resulted in a 4-fold up-regulation of RIP–luciferase expression compared with RIP alone. Note the marked pancreas specificity of luciferase expression. Only trivial activity was noted in liver and spleen, which lie along the ultrasound path. The left kidney, which is also in the path of the ultrasound beam, shows much less activity than the pancreas, but it does have glucose-regulatable expression of RIP–luciferase. The right kidney, which is outside the ultrasound path, shows no luciferase expression. There were three rats in each group. Differences in luciferase activity among organs were statistically significant by ANOVA (F = 74.86, P < 0.0001). Differences in plasmid (CMV vs. RIP vs. RIP with glucose feeding) were also statistically significant (F = 42.36, P < 0.0001).

The RIP–luciferase plasmid increased pancreatic luciferase activity by 4-fold compared with CMV–luciferase (298 ± 168 RLU/mg of protein vs. 68 ± 34 RLU/mg of protein; P < 0.0001). Glucose feeding further increased pancreatic luciferase activity by 3.5-fold over RIP–luciferase alone (1,084 ± 192 RLU/mg of protein vs. 298 ± 168 RLU/mg of protein; P < 0.0001), indicating that the RIP–luciferase transgene was appropriately regulated by glucose after delivery to islets by UTMD. Surprisingly, glucose feeding also caused regulation of luciferase expression in the left kidney compared with RIP–luciferase alone (172 ± 102 RLU/mg of protein vs. 53 ± 23 RLU/mg of protein; P = 0.0057), suggesting that the RIP responds to glucose even when localized in the kidney.

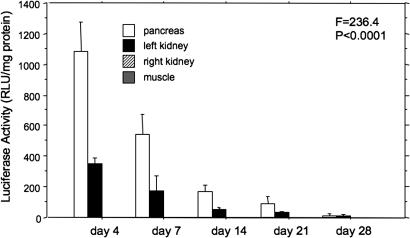

Time Course of Gene Expression by UTMD.

In a separate group of rats, the time course of gene expression by UTMD was measured with the RIP–luciferase plasmid. Luciferase activity was measured by killing three rats each at 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after UTMD. As shown in Fig. 3, luciferase activity drops by half from day 4 to day 7, and it is nearly undetectable by day 21 (F = 234, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 3.

Time course of RIP–luciferase expression. Luciferase activity declines from its peak at day 4, and it is negligible by day 28. The temporal decline in luciferase activity was statistically significant by ANOVA (F = 236.4, P < 0.0001). Muscle and kidney values are zero.

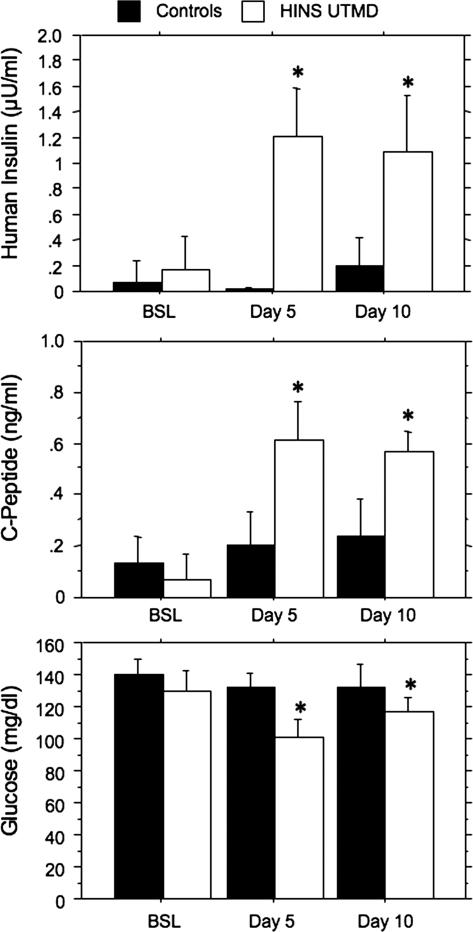

Delivery of Human Insulin Gene by UTMD.

In the first of two experiments to test the efficacy of the UTMD procedure in altering the biological function of pancreatic islets, we evaluated UTMD as a method for delivery of the human insulin gene to rat beta cells. To this end, we used a plasmid containing the human insulin gene under control of the RIP promoter. Six rats received RIP–human insulin by UTMD, and six rats served as controls (three sham and three treated with RIP–DsRed). Serum measurements of human insulin, human C-peptide, and glucose were compared with baseline, day 5, and day 10 after UTMD. As shown in Fig. 4, human insulin and C-peptide were “detectable” (because of crossreactivity with rat insulin and rat C-peptide) in the controls, but delivery of the RIP–human insulin plasmid by UTMD caused significant increases in both analytes (P < 0.0001 for both human insulin and C-peptide). In addition, serum glucose decreased from 130 ± 11 mg/dl at baseline to 102 ± 10 mg/dl and 116 ± 9 mg/dl at 5 and 10 days, respectively (P = 0.02).

Fig. 4.

Serum measurements of human insulin, human C-peptide, and glucose at baseline and after UTMD. (Top) Human insulin levels in rats receiving RIP–human insulin by UTMD (white bars) and in rats infused with RIP–DsRed-containing microbubbles (n = 3) and sham-operated normal rats (n = 3) (pooled as the black bars). By ANOVA, both the increase in human insulin from baseline to days 5 and 10 (F = 11.7, P = 0.0004) and the differences in insulin levels between controls and RIP–human insulin plasmid-treated rats (F = 74.5, P < 0.0001) were statistically significant. Asterisks show that human insulin levels were increased at days 5 and 10 compared with baseline and control values (P < 0.05 by post hoc test). (Middle) Similar plot showing C-peptide in control (black bars) vs. RIP–human insulin plasmid-treated (white bars) rats. The increase in C-peptide was statistically significant from baseline to days 5 and 10 (F = 23.5, P < 0.0001), as was the difference between controls and treated rats (F = 36.7, P < 0.0001). Asterisks show that human C-peptide levels were increased at days 5 and 10 compared with baseline and control values (P < 0.05 by post hoc test). (Bottom) Similar plot of glucose levels in control (black bars) vs. RIP–human insulin plasmid-treated (white bars) rats. Glucose levels were significantly lower over time (F = 10.1, P = 0.0009) and between groups (F = 21.1, P = 0.001). Asterisks show that glucose levels were decreased at days 5 and 10 relative to baseline and controls by post hoc tests.

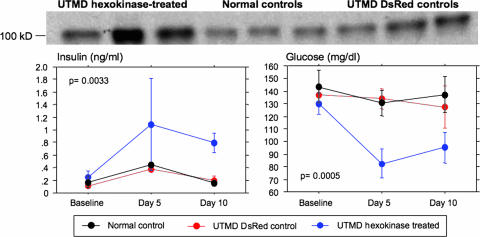

Regulation of Insulin Secretion and Circulating Glucose Levels by UTMD-Mediated Delivery of the Hexokinase I Gene.

As a second demonstration of the efficacy of the UTMD method, we chose a gene that must cause a significant change in beta cell metabolic function to cause a change in the whole-animal phenotype. Previous studies have demonstrated that overexpression of low-Km hexokinases (e.g., hexokinase I) results in a left shift in the glucose dose–response for insulin secretion because of increased stimulus–secretion coupling at low glucose (3, 23). We therefore tested whether UTMD-mediated delivery of a RIP–hexokinase plasmid could alter endogenous insulin production and glucose homeostasis in normal rats. Six rats were infused with microbubbles containing the RIP–hexokinase I plasmid, whereas controls included rats infused with RIP–DsRed-containing microbubbles (n = 3) and sham-operated normal rats (n = 3). Serum measurements of glucose and insulin were obtained at baseline and at days 5 and 10 after UTMD. As shown in Fig. 5, there was no significant change over time in serum insulin or glucose levels in the RIP–DsRed or sham-surgery control groups. In contrast, serum insulin increased by 4-fold at day 5 and remained elevated at day 10 in the RIP–hexokinase I-treated groups (F = 11.5, P = 0.0033 by repeated-measures ANOVA, treated vs. controls). Correlating with the increase in insulin, serum glucose levels decreased by nearly 30% in the RIP–hexokinase I-treated rats at day 5 (F = 19.8, P = 0.0005 by repeated-measures ANOVA, treated vs. controls) and then remained low until day 10. Further evidence of highly efficient delivery of the hexokinase I gene to pancreatic islets by UTMD is provided by immunoblot analysis of hexokinase I protein levels in islets isolated at day 10. These data show a clear increase in immunodetectable hexokinase I protein in islets of all six rats subjected to UTMD with the RIP–hexokinase I plasmid relative to either control group. In sum, the data of Fig. 5 clearly demonstrate the use of UTMD for high-efficiency gene delivery to pancreatic islet beta cells in living animals.

Fig. 5.

Insulin secretion and circulating glucose regulation by UTMD-mediated delivery of hexokinase I gene. (Upper) Western blot confirms hexokinase I expression in isolated rat pancreas after treatment with UTMD (three of six hexokinase-positive rats are shown), in normal controls (three), and in DsRed-treated controls (three). (Lower Left) Serum insulin levels in rats treated with hexokinase I by UTMD, DsRed control by UTMD, and sham-operated controls. Group differences were significant at P = 0.0033 by repeated-measures ANOVA, with a post hoc Scheffé’s test showing significant differences at days 5 and 10. (Lower Right) Serum glucose levels in rats treated with hexokinase I by UTMD, DsRed control by UTMD, and sham-operated controls. Group differences were significant at P = 0.0005 by repeated-measures ANOVA, with a post hoc Scheffé’s test showing significant differences at days 5 and 10. Data are shown as the mean ± 1 SD, with six (UTMD hexokinase), three (UTMD control), and three (normal control) rats per group.

Safety of UTMD.

Histologic sections of the pancreas did not reveal any evidence of inflammation or necrosis after UTMD. In four rats, serum amylase and lipase were measured at baseline, 1 h, and 24 h after UTMD; values were normal, and they did not increase with UTMD. Rats subjected to UTMD gained weight normally and demonstrated no abnormal behavior. Moreover, rats that received the RIP–DsRed plasmid experienced no significant changes in circulating glucose or insulin levels, suggesting maintenance of normal metabolic homeostasis.

Discussion

Although transgene expression in pancreatic islets of rodents has been achieved by microinjection of fertilized embryos (24–30), safe and efficient in vivo targeting of genes to pancreatic islets has been an elusive goal. This paper describes a method for efficient gene delivery to the pancreatic islets, with detection of transgene-encoded proteins (luciferase, human insulin and C-peptide, hexokinase I) for up to 3 weeks after transfection. This technique offers the ability to deliver genes to adult islets in vivo, avoiding potential developmental effects that might confound transgenic animal studies. Gene expression in the pancreas was confined to beta cells when UTMD was applied in conjunction with a plasmid in which RIP was used to direct transgene expression. Moreover, we demonstrated that the RIP–luciferase plasmid retained responsiveness to physiological signals after delivery to islets by UTMD because glucose feeding caused clear increases in reporter gene activity.

We thought that it was important to test the efficacy of the UTMD method by delivery of a gene that would be anticipated to modulate beta cell function. We chose the hexokinase I gene for this purpose. Pancreatic islet beta cells normally express hexokinase IV (also known as glucokinase) as their predominant glucose-phosphorylating enzyme, and the high half-saturating substrate concentration (S0.5) of the enzyme for glucose (≈6 mM) allows it to regulate the rate of glucose metabolism and control glucose-stimulated insulin secretion at physiologic glucose concentrations. Hexokinase I, in contrast, has a low S0.5 for glucose (≈0.5 mM). Adenovirus-mediated expression of hexokinase I in rat islets results in a left shift in glucose concentration-dependent changes in glycolysis and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (23). Moreover, expression of a low-Km yeast hexokinase in beta cells of transgenic mice was shown to cause hyperinsulinism and hypoglycemia (3). On the basis of these findings, we reasoned that efficient delivery of hexokinase I to beta cells by UTMD would be demonstrated by a similar phenotype of hyperinsulinism and hypoglycemia, which is exactly what we observed (see Fig. 5).

We also thought that it was important to determine whether delivery of the human insulin gene would result in the appropriate production of protein, cleavage of proinsulin into human insulin and C-peptide, and lowering of serum glucose. Our findings indicate that UTMD does not interfere with the ability of beta cells to secrete mature insulin produced by a proinsulin-expressing transgene.

The approach described provides safe and efficacious delivery of DNA constructs to beta cells, with several advantages. (i) No viral vectors are required for efficient gene transfer, limiting concerns for inflammatory responses or insertional mutagenesis. (ii) Use of the RIP in our plasmid constructs provides a remarkable degree of beta cell specificity within islets, with little or no expression of the DsRed reporter gene in glucagon-producing alpha cells. (iii) The microbubbles loaded with plasmid can be delivered by systemic circulation, obviating the need for invasive surgery such as would be required for local delivery to pancreatic vessels. (iv) There was no evidence of pancreatic damage arising as a result of microbubble infusion and local application of ultrasound in the pancreas.

We also encountered two unanticipated results. We found significant expression of the luciferase transgene under the control of the RIP in the left kidney, which lies in the path of the ultrasound beam when targeting the pancreas. No activity was present in the right kidney, which is outside the path of the ultrasound beam. Moreover, renal reporter gene expression was found to be responsive to glucose. An enhanced RIP has been shown to direct expression of human growth hormone in brain, thymus, and kidney in mice (31). Insulin is known to affect levels of adenosine (32) and expression of angiotensinogen (33) in the kidney. Further studies are warranted to explore the mechanism and possible utility of RIP-enhanced renal gene expression.

In addition, we were somewhat surprised that luciferase activity in pancreatic tissue was of lower magnitude with the CMV compared with the RIP promoter. Although widely considered to be a ubiquitous and promiscuous promoter, CMV has been shown to be much more potent in exocrine pancreas than islets (34). Moreover, it is possible that the high levels of proteases in exocrine pancreas might have reduced CMV-mediated luciferase activity in nonislet tissues.

The technology described in this study has implications for the treatment of both major forms of diabetes, and it also represents a method of testing the relevance of candidate disease genes in the endocrine pancreas. Our method will allow a rapid means of testing beta cell candidate genes that emerge from human genetic studies in the context of adult animals. Finally, with the advent of technologies for suppression of gene expression, such as small interference RNAs (siRNAs), and their application to pancreatic islets (35, 36), one can envision UTMD-mediated delivery of siRNA-containing plasmids as a means of assessing the roles of specific genes in beta cell function and survival in living animals.

Materials and Methods

Rat UTMD Protocol.

Sprague–Dawley rats (250–350 g) were anesthetized with i.p. ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). A polyethylene tube (PE 50; Becton Dickinson) was inserted into the right internal jugular vein by cutdown. The anterior abdomen was shaved, and an S3 probe (Sonos 5500; Philips Ultrasound, Andover, MA) was placed to image the left kidney and spleen, which are easily identified. The pancreas lies between them, so the probe was adjusted to target the pancreas and clamped in place. Plasmid DNA containing the reporter genes LacZ, DsRed, or luciferase, or the hexokinase I gene under the regulation of either CMV or RIPs were incorporated within the phospholipid shell of perfluoropropane gas-filled microbubbles. One milliliter of microbubble suspension was infused at a constant rate of 3 ml/h for 20 min. Ultrasound was directed at the pancreas to destroy these microbubbles within the pancreatic microcirculation; microbubble infusion without ultrasound was also used as a control. Throughout the infusion, microbubble destruction was achieved by using the ultraharmonic mode (transmit 1.3 MHz/receive 3.6 MHz) with a mechanical index of 1.2–1.4 and a depth of 4 cm. The ultrasound pulses were ECG-triggered (at 80 ms after the peak of the R wave) to deliver a burst of four frames of ultrasound every four cardiac cycles. These settings have previously been shown to be the optimal ultrasound parameters for gene delivery using UTMD (11). At the end of each experiment, the jugular vein was tied off, and the skin was closed. All rats were monitored after the experiment for normal behavior. Rats were killed 4 days later, and the pancreas was removed for further analysis.

Manufacture of Plasmid-Containing Lipid-Stabilized Microbubbles.

Lipid-stabilized microbubbles were as described in ref. 11. A stock solution of 250 mg of DPPC (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) (Sigma), 50 mg of DPPE (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) (Sigma), and 10% wt/vol glucose was mixed with PBS to a final volume of 10 ml. This mixture was boiled in water until all powder was fully dissolved. Then, 2 mg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 0.5 ml of ethyl alcohol and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and the DNA pellet was placed in an incubator at 37°C for 5 min to remove any remaining ethyl alcohol. The DNA was then added to 50 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (1 mg/ml; GIBCO) and mixed for 20 min until fully dissolved. This DNA/Lipofectamine was then added to 250 μl of liposome stock solution, 5 μl of 10% albumin, and 50 μl of glycerol (10 mg/ml) in 1.5-ml vials, mixed well, and placed on ice. The headspace of the vial was then filled with perfluoropropane gas (Air Products and Chemicals, Allentown, PA), capped, and shaken for 30 min at 4°C. The lipid-stabilized microbubbles appear as a milky white suspension floating on the top of a layer of liquid containing unincorporated plasmid DNA. The subnatant was discarded, and the microbubbles were washed three times with PBS to remove unincorporated plasmid DNA. The mean diameter and concentration of the microbubbles in the upper layer were measured by a particle counter (Multisizer III; Beckman Coulter). The mean diameter and concentration of the microbubbles were 1.9 ± 0.2 μm and 5.2 ± 0.3 × 109 bubbles per ml, respectively. The amount of plasmid carried by the microbubbles was 250 ± 10 μg/ml.

Plasmid Constructs.

Rat genomic DNA was extracted from rat peripheral blood with a QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A RIP fragment, spanning nucleotides −412 to +155 (from transcription start site 4006, rat insulin 1, GenBank J00747) was isolated and inserted into the plasmids. This 567-bp fragment containing exon 1, intron 1, and 3 bp (GTC) of the 5′ end of exon 2 was PCR-amplified from Sprague–Dawley rat DNA by using the following PCR primers that contain a restriction site at the 5′ ends (the restriction sites are underlined): primer 1 (XhoI), 5′-CAACTCGAGGCTGAGCTAAGAATCCAG-3′; and primer 2 (EcoRI), 5′-GCAGAATTCCTGCTTGCTGATGGTCTA-3′.

The corresponding PCR products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). To confirm the sequences, direct sequencing of PCR products was performed with the dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on Applied Biosystems’ 3100 genomic analyzer. The PCR-amplified fragments were digested with XhoI and EcoRI and then ligated into the XhoI–EcoRI sites of pDsRed–Express 1, a promoterless DsRed plasmid (BD Biosciences). Ligation reactions were carried out in 20 μl of 20 mM Tris·HCl/0.5 mM ATP/2 mM DTT/1 unit of T4 DNA ligase. Cloning, isolation, and purification of this plasmid were performed by standard procedures, and once again the PCR products were sequenced to confirm that no artifactual mutations were present. RIP–hexokinase I and RIP–human insulin were made in the same manner.

Immunohistochemistry for Detection of DsRed Protein, Insulin, and Glucagon.

Cryostat sections 5 μm in thickness were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4°C and quenched for 5 min with 10 mM glycine in PBS. Sections were then rinsed in PBS three times and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Sections were blocked with 10% vol/vol goat serum at 37°C for 1 h and washed three times with PBS. The primary antibody (Sigma) (1:50 dilution in block solution) was added and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS three times for 5 min each time, the secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC; Sigma) (1:50 dilution in block solution) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Sections were rinsed five times with PBS for 10 min each time and then mounted.

Luciferase Assay.

To quantitate expression of the luciferase transgene, the pancreas, both kidneys, spleen, and skeletal muscle were pulverized in a Polytron (Brinkmann) and incubated with luciferase lysis buffer (Promega)/0.1% Nonidet P-40/0.5% deoxycholate/proteinase inhibitors. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and 100 μl of luciferase reaction buffer (Promega) was added to 20 μl of the clear supernatant. Light emission was measured by a luminometer (TD-20/20; Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA) in RLU. Total protein content was determined by using bicinchoninic acid (37) (BCA protein assay reagent; Pierce) from an aliquot of each sample. Luciferase activity was expressed as RLU/mg of protein.

Human Insulin and C-Peptide Assays.

Human insulin and C-peptide were measured with a commercially available RIA kit (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). The crossreactivity of the human assay kit with rodent proteins is <0.4%.

Hexokinase I Western Blot.

Sections of whole pancreas were harvested when each rat was killed (day 10 after the UTMD gene delivery), and the sections were homogenized in Tris buffer. Equal amounts of protein from these tissue homogenates were subjected to electrophoresis in a 12% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad), blocked, and incubated with mouse anti-hexokinase I antibody. Immunoreactive bands were visualized with chemiluminescent substrate (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia).

Statistical Analysis.

Differences in luciferase activity between experimental groups were compared with two-way ANOVA. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to evaluate the results of the time course experiment. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the temporal change in serum insulin and glucose between hexokinase 1-treated rats and control groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Post hoc Scheffé tests were performed only when the ANOVA F values were statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 DK58398 and the Mark Shepherd endowed chair of the Baylor Foundation.

Abbreviations

- DsRed

Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein

- RIP

rat insulin 1 promoter

- RLU

relative light units

- UTMD

ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Winer N., Sowers J. R. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;44:397–405. doi: 10.1177/0091270004263017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaoka T. Curr. Mol. Med. 2001;1:325–337. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker T., Beltran del Rio H., Noel R. J., Johnson J. H., Newgard C. B. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:21234–21238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flotte T., Agarwal A., Wang J., Song S., Fenjves E. S., Inverardi L., Chesnut K., Afione S., Loiler S., Wasserfall C., et al. Diabetes. 2001;50:515–520. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang A. Y., Pend P. D., Ehrhardt A., Storm T. A., Kay M. A. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:405–413. doi: 10.1089/104303404322959551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayuso E., Chillon M., Agudo J., Haurigot V., Bosch A., Carretero A., Otaegui P. J., Bosch F. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:805–812. doi: 10.1089/1043034041648426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koehler D. R., Hannam V., Belcastro R., Steer B., Wen Y., Post M., Downey G., Tanswell A. K., Hu J. Mol. Ther. 2001;4:58–65. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tirone T. A., Fagan S. P., Templeton N. S., Wang X. P., Brunicardi F. C. Ann. Surg. 2001;233:603–611. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tirone T. A., Wang X. P., Templeton N. S., Lee T., Nguyen L., Fisher W., Brunicardi F. C. World J. Surg. 2004;28:826–833. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shohet R. V., Chen S., Zhou Y.-T., Wang Z.-W., Meidell R. S., Unger R. H., Grayburn P. A. Circulation. 2000;101:2554–2556. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S., Shohet R. V., Bekeredjian R., Frenkel P. A., Grayburn P. A. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekeredjian R., Chen S., Frenkel P., Grayburn P. A., Shohet R. V. Circulation. 2003;108:1022–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084535.35435.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korpanty G., Chen S., Shohet R. V., Ding J.-h., Yang B.-z., Frenkel P. A., Grayburn P. A. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1305–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekeredjian R., Grayburn P. A., Shohet R. V. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frenkel P. A., Chen S., Thai T., Shohet R. V., Grayburn P. A. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002;28:817–822. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wentworth B. M., Schaefer I. M., Villa-Komaroff L., Chirgwin J. M. J. Mol. Evol. 1986;23:305–312. doi: 10.1007/BF02100639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deltour L., Leduque P., Blume N., Madsen O., Dubois P., Jami J., Bucchini D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:527–531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Throsby M., Homo-Delarche F., Chevenne D., Goya R., Dardenne M., Pleau J.-M. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2399–2406. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chentoufi A. A., Polychronakos C. Diabetes. 2002;51:1383–1390. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chentoufi A. A., Palumbo M., Polychronakos C. Diabetes. 2004;53:354–359. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamotte L., Jackerott M., Bucchini D., Jami J., Joshi R. L., Deltour L. Transgenic Res. 2004;13:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s11248-004-9587-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S. Y., Wang X., Chen X., Powers A. C., Magnuson M. A., Head W. S., Piston D. W., Bell G. I. Genesis. 2005;43:80–86. doi: 10.1002/gene.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein P. N., Boschero A. C., Atwater I., Cai X., Overbeek P. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:12038–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto K., Hashimoto H., Tomimoto S., Shintani N., Miyazaki J., Tashiro F., Aihara H., Nammo T., Li M., Yamagata K., et al. Diabetes. 2003;52:1155–1162. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara M., Wang X., Kawamura T., Bindokas V. P., Dizon R. F., Alcoser S. Y., Magnuson M. A., Bell G. I. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;284:E177–E183. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marron M. P., Graser R. T., Chapman H. D., Serreze D. V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13753–13758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212221199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cebrian A., Garcia-Ocana A., Takane K. K., Sipula D., Stewart A. F., Vasavada R. C. Diabetes. 2002;51:3003–3013. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain M. A., Miller C. P., Habener J. F. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:16028–16032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuttle R. L., Gill N. S., Pugh W., Lee J. P., Koeberlein B., Furth E. E., Polonsky K. S., Naji A., Birnbaum M. J. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorens B., Guillam M. T., Beermann F., Burcelin R., Jaquet M. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23751–23758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stellrecht C. M., DeMayo F. J., Finegold M. J., Tsai M. J. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3567–3572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawelczyk T., Podgorska M., Sakowicz M. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:81–88. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S. L., Chen X., Wei C. C., Filep J. G., Tang S. S., Ingelfinger J. R., Chan J. S. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4627–4635. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhan Y., Brady J. L., Johnston A. M., Lew A. M. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:639–645. doi: 10.1089/10445490050199045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng Y., Yi R., Cullen B. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9779–9784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630797100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bain J., Schisler J. C., Takeuchi K., Newgard C. B., Becker T. C. Diabetes. 2004;53:2190–2194. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown R. E., Jarvis K. L., Hyland K. J. Anal. Biochem. 1989;180:136–139. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]