Abstract

The PAR-3/PAR-6/atypical PKC (aPKC) complex is required for axon–dendrite specification of hippocampal neurons. However, the downstream effectors of this complex are not well defined. In this article, we report a role for microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK)/PAR-1 in axon–dendrite specification. Knocking down MARK2 expression with small interfering RNAs induced formation of multiple axon-like neurites and promoted axon outgrowth. Ectopic expression of MARK2 caused phosphorylation of tau (S262) and led to loss of axons, and this phenotype was rescued by expression of PAR-3, PAR-6, and aPKC. In contrast, the polarity defects caused by an MARK2 mutant (T595A), which is not responsive to aPKC, were not rescued by the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex. Moreover, polarity was abrogated in neurons overexpressing a mutant of MARK2 with a deleted kinase domain but an intact aPKC-binding domain. Finally, suppression of MARK2 rescued the polarity defects induced by a dominant-negative aPKC mutant. These results suggest that MARK2 is involved in neuronal polarization and functions downstream of the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex. We propose that aPKC in complex with PAR-3/PAR-6 negatively regulates MARK(s), which in turn causes dephosphorylation of microtubule-associated proteins, such as tau, leading to the assembly of microtubules and elongation of axons.

Keywords: polarity complex, partition-defective protein 1b, axon specification

Typical mature neurons have one axon and multiple dendrites. They receive information at the dendrites and send signals to other neurons via the axons. Thus, proper polarization of neurons is important for brain wiring. Cultured hippocampal neurons are a model system for studying neuronal polarity (1–3). They form lamellipodia shortly after plating (stage 1). Within 12–24 h, they extend several minor processes with dynamic growth cones that are indistinguishable in length (stage 2). After an additional 12 to 24 h, one of the processes grows faster and becomes the axon (stage 3), whereas other neurites grow at a slower rate and become dendrites (1, 3). Axons and dendrites also differ in their composition of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), with dephospho-tau (Tau1) and MAP1b rich in axons and MAP2 rich in dendrites (4–7).

Polarization is regulated by the intrinsic activity of developing neurons, and intracellular pathways that specify axon formation are just beginning to be understood (3, 8, 9). Regulation of local microtubule (MT) and actin organization is critical for neuronal polarization (2, 3, 7, 10). For example, hippocampal neurons isolated from mice lacking both tau and MAP1b showed strong defects in neuronal polarity (11). The crucial role of another MT-binding protein, CRMP-2, in neuronal polarization is determined by its dephosphorylation resulting from glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) inhibition (12). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is necessary for establishment and maintenance of neuronal polarity, probably by inhibiting GSK3β (12, 13). In addition, the evolutionarily conserved tripartite complex of PAR-3, PAR-6, and atypical PKC (aPKC) is involved in axon specification of hippocampal neurons (14–16), although not in Drosophila (17). Upstream of this complex may be Rap1B, a GTPase localized at the tip of a single neurite (16). The PAR complex in association with the GEF protein STEF/Tiam regulates Rac activation by Cdc42, a process required for neuronal polarization (18). However, how the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex functions to regulate neuronal polarity remains unknown. Considering the importance of microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK)/PAR-1, a family of serine/threonine protein kinases implicated in polarization of epithelial cells (19, 20) and in MT disassembly (21, 22), we investigated the contribution made by MARK2/PAR-1b to neuronal polarization.

In this article, we report that suppressing MARK2 expression in hippocampal neurons promotes axon outgrowth and results in neurons containing several rather than a single axon. Ectopic MARK2 expression causes neurons to lose axons and become unpolarized. Moreover, MARK2 activity is opposed by the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC polarity complex. Importantly, suppressing MARK2 expression rescues the neuronal polarity defect observed in cells expressing an aPKC mutant, and expression of an MARK2 mutant lacking kinase domain but retaining aPKC-binding ability abrogates neuronal polarity. These findings indicate that MARK2 is negatively regulated by the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC polarity complex.

Results

Suppressing MARK2 Induces Formation of Multiple Axons.

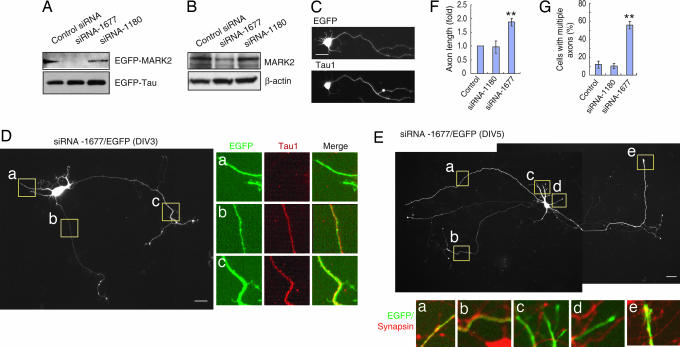

MARK2 is negatively regulated by aPKC, which phosphorylates MARK2 on T595 (26). Interestingly, the ratio of p-MARK2 (T595)/MARK2 in axon tips of stage-3 neurons was significantly higher than that in dendrite tips (for details, see Supporting Results and Fig. 6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To explore the function of MARK2, we designed two small interfering RNAs (siRNA), siRNA-1677 and -1180. siRNA-1677 suppressed MARK2 expression in transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells compared with control siRNA, whereas siRNA-1180 had little effect (Fig. 1A). Importantly, expression of EGFP-tau was not affected by the MARK2-specific siRNA (Fig. 1A). The effect of siRNA was also examined in primary neurons in which endogenous MARK2 was suppressed by siRNA-1677 but not siRNA-1180 (Fig. 1B). To examine the effects of the MARK2-siRNA on neuronal polarity, hippocampal neurons were electroporated with MARK2-siRNAs, together with an EGFP plasmid before plating and were analyzed at 3 days in vitro (DIV3) for their ability to polarize. As seen in Fig. 1, neurons expressing EGFP alone showed normal polarity, as indicated by the presence of a single process labeled with the axonal marker Tau1 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the majority (≈63%) of neurons transfected with siRNA-1677 developed multiple long processes that stained positive for Tau1, identifying them as axons (Fig. 1 D and G). Only a small fraction of neurons transfected with either control siRNA (≈13%) or siRNAi-1180 (≈12%) grew multiple axon-like processes (Fig. 1G). Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, showed that siRNA-1677-treated neurons had multiple long processes labeled with TUJ1, and these processes were longer than the single axons of neighboring nontransfected cells (see Fig. 7C). Synapsin, another axonal marker in mature neurons (24), was also seen in the multiple long processes generated in MARK2-siRNA-treated cells at DIV5 (Fig. 1E), further confirming their axonal properties. Transfection with MARK2-siRNA-1677 caused a 2-fold increase in axon length, whereas MARK2-siRNA-1180 had no apparent effect (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, siRNA-1677-transfected cells often exhibited numerous long protrusions along their axon-like processes (see Fig. 7 D, F, and G), reminiscent of dynamic F-actin (see Fig. 7B). These structures were rarely observed in control cells (see Fig. 7E).

Fig. 1.

Suppressing MARK2 induces formation of multiple axons. (A) HEK-293 cells were transfected with the same amount of EGFP-MARK2 and tau together with control siRNA or MARK2 siRNA-1677 or -1180. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against MARK2 or GFP. (B) Primary neurons were transfected with siRNAs and cultured for 72 h. The levels of endogenous MARK2 were assessed by immunoblotting and normalized with β-actin. (C) Hippocampal neurons transfected with EGFP plasmid were stained with Tau1 antibody at DIV3. (D) Neurons transfected with siRNA-1677/EGFP were stained with Tau1 antibody at DIV3. The boxed areas indicate dendrite-like (a) or axon-like (b and c) neurites. (E) Neurons transfected with MARK2-siRNA-1677/EGFP were stained with antibody against synapsin at DIV5. The boxed areas indicate dendrite-like (c and d) or axon-like (a, b, and e) neurites. (F) Quantitative analysis of axon length in siRNA-transfected neurons. All of the experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are shown as means ± SEM, and ≥60 cells were analyzed for each treatment per experiment. Axon length in control siRNA-transfected neurons was taken as 1.0. ∗∗, P < 0.01. (G) MARK2-siRNA-1677 increases the percentage of cells with multiple axons. Data are means ± SEM. ∗∗, P < 0.01.

aPKC Inhibits MARK2 Phosphorylation of Tau.

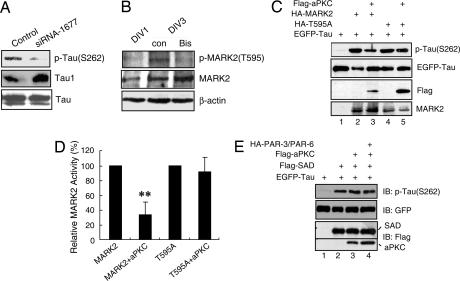

How does MARK2 specify axon formation? MARK phosphorylates MAPs, such as doublecortin, MAP2, MAP4, and tau, to trigger MT disassembly (21, 22, 25). As shown in Fig. 2, knocking down MARK2 expression with siRNA-1677 in primary neurons resulted in a decrease of tau phosphorylation at S262 and an increase of Tau1, whereas the level of total tau was not altered (Fig. 2A). This result suggests the involvement of MARK2 in phosphorylating tau in vivo. aPKC associates with and phosphorylates MARK2/PAR-1 on a specific site, T595 in PAR-1b (20, 26, 27), leading to a loss of plasma membrane binding and inhibition of MARK2/PAR-1b kinase activity (26). Consistent with the positive staining of p-MARK2 (T595) in neurons at stage 3 (Fig. 6F), immunoblotting revealed that the level of p-MARK2 (T595) in hippocampal neurons was high on day 3 (with most neurons in stage 3) but low on day 1 (with most neurons in stages 1 and 2) (Fig. 2B). Bisindolylmaleimide, an inhibitor of PKC, significantly decreased MARK2 phosphorylation at T595 (Fig. 2B). In agreement with this result, overexpression of MARK2 in HEK-293 cells or PC12 cells increased tau phosphorylation at S262 (Fig. 2C and see Fig. 8A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, when aPKC was cotransfected with MARK2, the phosphorylation of tau (S262) was significantly decreased (Fig. 2 C and D and see Fig. 8A). In contrast, aPKC did not block the ability of MARK2T595A, a mutant that retains kinase activity but cannot be phosphorylated by aPKC (26), to phosphorylate tau (Fig. 2 C, lanes 4 and 5, and D).

Fig. 2.

MARK2-mediated tau phosphorylation at S262 is inhibited by aPKC. (A) Primary neurons were transfected with control or siRNA-1677 and cultured for 72 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against p-tau (S262), Tau1, or total tau. (B) Hippocampal neurons at DIV1 or DIV3 were treated without or with 5 μM bisindolylmaleimide (Bis) for 7 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. (C) Lysates of HEK-293 cells transfected with EGFP-tau alone or together with indicated plasmids were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against p-tau (S262) or individual tags. (D) Quantitative analysis of data in C. The relative amount of tau (S262) against total tau was normalized to represent MARK2 activity, with that from MARK2 or T595A transfection alone as 100%. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 3; ∗∗, P < 0.01). (E) Lysates of HEK-293 cells transfected with indicated plasmids were subjected to immunoblotting.

The SAD kinases contain a kinase domain related to that of MARK2 (50–52% amino acid homology in the kinase domain) but diverge outside of the kinase domain (28). Consistent with ref. 28, overexpression of SAD-B caused phosphorylation of tau (S262) (Fig. 2 E, lanes 1 and 2). However, SAD phosphorylation of tau (S262) did not appear to be regulated by aPKC, even in the presence of PAR-3 and -6 (Fig. 2 E, lanes 2–4). These results demonstrate the specificity of aPKC for MARK2.

MARK Is Involved in Neuronal Polarity Specification.

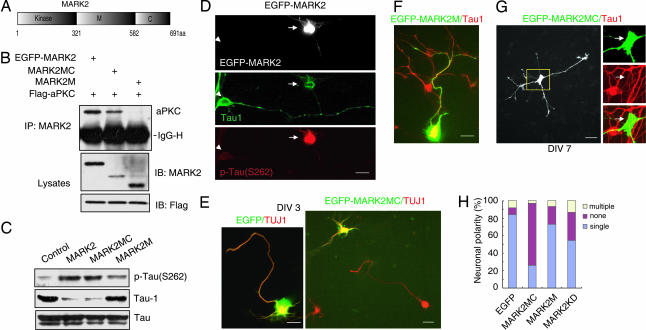

MARK2 has a kinase domain at its amino terminus, followed by a divergent middle (M) region and a conserved carboxyl-terminal (C) region (Fig. 3A) (29). To test which domain of MARK2 interacts with aPKC, HEK-293 cells were transfected with vectors encoding Flag-aPKC together with EGFP-MARK2 or mutants. As shown in Fig. 3, aPKC associated with MARK2 and the fragment containing the M and C regions (amino acids 321–691), but not the M region alone (amino acids 321–582) (Fig. 3B). To further explore the role of MARK2 in neuronal polarity, primary neurons were transfected with wild-type or mutant forms of MARK2. Ectopic expression of MARK2 resulted in enhanced phosphorylation of tau at S262 (Fig. 3C). The level of dephospho-tau (Tau1) was decreased by MARK2, whereas total tau remained constant (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, MARK2MC, which lacks kinase domain but retains aPKC-binding ability, also caused an increase of p-tau (S262) and a decrease of Tau1 (Fig. 3C). MARK2M, however, which does not interact with aPKC, had no apparent effect on tau phosphorylation (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The role of MARK2 and its mutants in neuronal polarity. (A) Schematic diagrams of MARK2 structure. (B) HEK-293 cells were transfected with Flag-PKCζ and EGFP-tagged MARK2 constructs. The immunoprecipitates with anti-MARK2 antibody were subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. IgG-H, IgG heavy chain. (C) Primary neurons were transfected with MARK2 constructs or control plasmid and cultured for 48 h. The levels of different tau isoforms were accessed by immunoblotting. (D) Neurons transfected with EGFP-MARK2 were stained at DIV3 with antibodies against different tau isoforms, Tau1, and p-tau (S262). Note that the EGFP-MARK2-positive cell (arrow) stained strongly for p-tau (S262) but weakly for Tau1, in comparison with the nontransfected cell (arrowhead). (E) Neurons transfected with EGFP-MARK2MC or EGFP were stained with anti-TUJ1 antibody at DIV3. Note that EGFP-MARK2MC-expressing cells were unpolarized, whereas the neighboring untransfected cells were polarized. (F) Neurons transfected with EGFP-MARK2M were stained with Tau1 antibody at DIV3. (G) Neurons transfected with EGFP-MARK2MC were stained with Tau1 antibody at DIV7. Note that MARK2MC-expressing cells (arrows) stained low for Tau1 signal in comparison with the neighboring nontransfected cell. (H) Quantitative analysis of neuronal polarity. None, neurons with short neurites in similar length; single, neurons with one Tau1-positive process >100 μm and at least twice as long as the second longest process; multiple, neurons with two or more Tau1-positive processes >100 μm and twice as long as other neurites. The data were obtained from three independent experiments. At least 90 cells for each construct were analyzed per experiment.

Next, we characterized the effects of MARK2 on neuronal polarity by expressing wild-type or mutant forms of MARK2 in hippocampal neurons. After being transfected with EGFP-MARK2, only a few neurons attached to poly-d-lysine-coated plates; these neurons showed increased p-tau (S262) staining, but even after culturing for 72 h, they did not develop axons (Figs. 3D and 4E). We used MARK2 mutants to investigate the role of MARK2/aPKC interactions in neuronal polarity. Interestingly, the majority of neurons expressing EGFP-MARK2MC did not polarize. These neurons possessed several minor processes labeled with TUJ1 and lacked a single axon-like long process (polarized neurons with a single axon, 85 ± 6.1% for EGFP and 27 ± 5.0% for EGFP-MARK2MC; P < 0.01; Fig. 3 E and H). In contrast, MARK2M expression had little effect on polarity (polarized neurons with a single axon, 73 ± 6.6%; P > 0.05; Fig. 3 F and H). To test whether the effect of MARK2MC on polarity was due to delayed neurite growth, we observed the phenotype at later stages. After being transfected with MARK2MC, most neurons failed to polarize even after DIV7, although the neurites kept growing (Fig. 3G). MARK2MC-transfected neurons also showed a decrease of Tau1 staining at DIV7 (Fig. 3G). In addition, neurons transfected with a kinase-inactive mutant of MARK2 (MARK2KD) also showed polarity defects (polarized neurons with a single axon, 54 ± 6.1% for MARK2KD and 85 ± 6.1% for EGFP; P < 0.01; Fig. 3H).

Fig. 4.

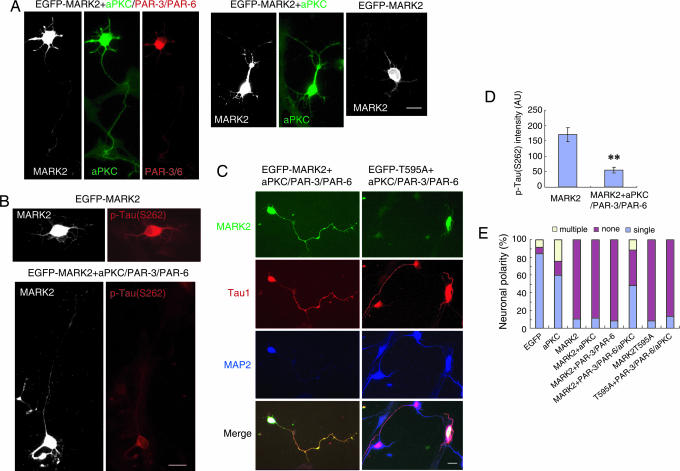

The PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex counteracts the polarity defect caused by ectopic MARK2 expression. (A) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with EGFP-MARK2, together with Flag-aPKC, or hemagglutinin (HA)-PAR-3 plus PAR-6, or Flag-aPKC plus PAR-3 and PAR-6 with the ratio of 1:3:3:3 (MARK2/PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC). Transfected cells at DIV3 were stained with rabbit polyclonal antibody against aPKC and mouse monoclonal antibody against HA to monitor levels of exogenously expressed aPKC and PAR-3/6. Immunoreactivity was visualized by Alexa Fluor 350-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody and rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody, respectively. Shown are the examples of hippocampal neurons transfected with various plasmid combinations. (B) Neurons transfected with EGFP-MARK2, and with or without aPKC plus PAR-3 and PAR-6, were stained with antibody against p-tau (S262) at DIV3. (C) Neurons were transfected with EGFP-MARK2 or the T595A mutant, together with aPKC plus PAR-3 and PAR-6 (1:3:3:3), and stained with antibodies against Tau1 and MAP2 at DIV3. (D) Quantitative analysis of the immunofluorescence intensity of p-tau (S262). The intensity of p-tau (S262) in GFP-MARK2-positive cells, with or without PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC, was plotted. AU, arbitrary unit. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 13; ∗∗, P < 0.01). (E) Quantitative analysis of polarity phenotype. The data were obtained from three independent experiments. At least 90 cells for each transfection were analyzed per experiment.

PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC Counteract MARK2 in Axon Formation.

Inhibition of MARK2 by aPKC is predicted to decrease tau phosphorylation, which is expected to enhance MT assembly and axon elongation. Thus, overexpressing aPKC might rescue the polarity defects caused by ectopic MARK2 expression. However, ectopic aPKC was unable to rescue the defects caused by MARK2 (Fig. 4 A and E). Surprisingly, coexpression of all three components of the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex did exhibit a rescue effect (Fig. 4 A–C, and E). Approximately half of the cells expressing EGFP-MARK2 together with PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC exhibited normal polarity, with at least one long process staining strongly for Tau1 (Fig. 4 C and E). In contrast, only 10% of cells cotransfected with MARK2 and either aPKC or PAR-3 plus PAR-6 polarized normally (Fig. 4 A and E). Thus, the appropriate ratio of the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC components and MARK2 in hippocampal neurons is essential for proper polarization. The inability of aPKC alone to exhibit rescue effects in primary neurons might be due to its inappropriate localization in the absence of PAR-3 and PAR-6. Indeed, ectopic expression of aPKC alone increased the percentage of neurons with multiple axons and decreased the percentage of neurons with a single axon (Fig. 4E), an effect similar to that induced by ectopic PAR-3 expression (14, 18). Consistent with the rescue effect, MARK2 phosphorylation of tau (S262) was inhibited in cells cotransfected with the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex (Fig. 4 B and D). Thus, aPKC in complex with PAR-3 and PAR-6 may function to prevent MARK2 from phosphorylating tau in vivo. Neurons transfected with MARK2 (T595A) also failed to polarize properly (Fig. 4E). Unlike wild-type MARK2, however, the defects caused by the T595A mutant could not be rescued by cotransfection with the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex (Fig. 4 C and E).

Knockdown of MARK2 Rescues the Polarity Defect Caused by aPKC Mutant.

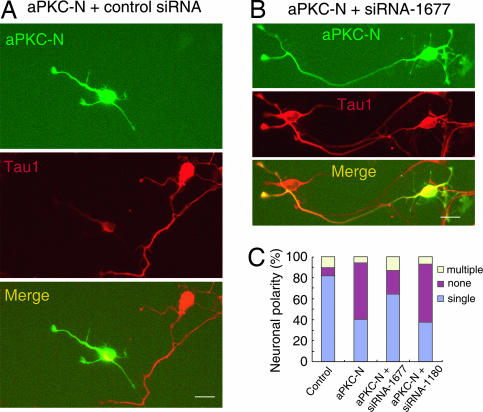

aPKC has an amino-terminal PB1 domain that binds PAR-6, followed by a Zn-finger domain of unknown function and a kinase domain that binds to and phosphorylates PAR-3 (30, 31). Expression of the amino-terminal PB1 domain (aPKC-N) dramatically reduced the percentage of neurons with a single axon (41 ± 5.3% for PKC-N and 82 ± 4.8% for EGFP; P < 0.01; Fig. 5A and C), presumably by interfering with endogenous PAR-6/aPKC interactions. When neurons were cotransfected with MARK2 siRNA-1677 and aPKC-N, however, the polarity defects were partially rescued with the majority of neurons exhibiting normal polarity with single axons (64 ± 5.6%; P < 0.01 compared with aPKC-N). In contrast, siRNA-1180 did not exhibit any rescue effects (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Knockdown MARK2 rescues the polarity defect caused by DN-aPKC. (A and B) Hippocampal neurons were transfected with aPKC-N, together with EGFP plasmid, and control (A) or MARK2 siRNA (B), and stained with Tau1 antibody at DIV3. (C) Quantitative analysis of neuronal polarity. The data were obtained from three independent experiments. At least 90 cells for each transfection were analyzed per experiment.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of MARK/PAR-1 in determining neuronal polarity. We report that: (i) ectopic expression of MARK2 in hippocampal neurons results in an increase of tau phosphorylation at S262 and a loss of neuronal polarity; these MARK2-induced phenotypes were rescued by coexpression of the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC polarity complex; (ii) reducing MARK2 levels in hippocampal neurons promotes axon outgrowth resulting in neurons containing several axons, rather than a single one, and reducing MARK2 levels rescues polarity defects induced by expression of a dominant-negative aPKC mutant; and (iii) perturbing endogenous MARK2 interactions with aPKC by overexpressing an MARK2 mutant (MARK2MC) abrogates neuronal polarity. Taken together, these results suggest that MARK2 inhibition by aPKC plays an active role in regulating neuronal polarity and, in particular, in regulating axon development. We propose that aPKC, when complexed with PAR-3 and PAR-6, negatively regulates MARK(s), which in turn leads to dephosphorylation of MAPs such as tau, and finally promotes the assembly of stable MTs and axon elongation.

Modulation of MT stability by phosphorylation of MAPs appears to be a major determinant for axon specification (3, 8, 11). MARK2 phosphorylates tau at S262 (23, 32), which reduces tau binding to MTs (33). Similar to the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex (15, 16, 34), both MARK2 and an inhibited form of MARK2, p-MARK2 (T595), distributed mainly in axons of hippocampal neurons at stage 3. In contrast, p-tau (S262) was concentrated in dendrites but absent from axons (Fig. 6) (28), indicating that MARK2 is inactivated in the developing axons. The findings that PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex and aPKC activity are essential for the establishment of neuronal polarity (15, 16, 34) and that aPKC interacts with and negatively regulates MARK2 (26) led us to postulate that PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC might function by negatively regulating MARK2 in neuronal polarization. The ability of aPKC to inhibit MARK2-mediated tau phosphorylation was demonstrated in HEK-293 cells (Fig. 2), PC12 cells (see Fig. 8), and primary neurons (Fig. 4). Knocking down MARK2 levels with siRNA decreased tau phosphorylation at S262, induced formation of multiple axon-like neurites, and promoted axon outgrowth. These results imply that some fraction of MARK2, such as that in dendrites or soma, might be in an active state in which inhibition is sufficient to promote MT assembly and axon outgrowth.

Expression of an MARK2 mutant (MARK2MC) lacking a kinase domain but retaining aPKC-binding domain caused tau phosphorylation and polarity defects (Fig. 3), presumably by preventing aPKC from negatively regulating endogenous MARK2. These findings further support the conclusion that aPKC negatively regulates MARK2 to promote neuronal polarity. Additional support for this conclusion comes from the following observations: inhibition of aPKC in hippocampal neurons led to decreased levels of p-MARK2 (T595), an “inhibited” form of MARK2 (Fig. 2B); expression of the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC complex partially rescued the phenotype induced by overexpression of wild-type MARK2 but not the T595A phosphorylation mutant; and lastly, MARK2 knockdown partially rescued the polarity defects caused by expression of a dominant-negative aPKC mutant (Fig. 5).

Inhibition of GSK3β by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway is essential for neuronal polarization (12, 13). The substrates of GSK3β include several MAPs, such as CRMP-2, MAP1B, tau, and APC, in which phosphorylation prevents interaction with MTs (12, 35–38). Interestingly, GSK3β phosphorylation of tau requires prior phosphorylation by PAR-1 in Drosophila (32). It will be interesting to investigate whether GSK3β phosphorylation of tau also requires MARKs in the mammalian system. A recent study suggests a causal relationship between PAR-1 and GSK3β, whereby GSK3β directly phosphorylates and activates MARK2/PAR-1 (39). Another possibility is that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/GSK3β pathway acts in parallel with the PAR-3/PAR-6/aPKC/MARK2 pathway in establishing neuronal polarity. Activation of either pathway may be sufficient to promote MT assembly and axon elongation.

Expression of PAR-1/MARK2 in neuroblastoma N2a cells promotes neurite outgrowth, whereas the formation of neurites is blocked if MARK2 is inactivated (23). In addition, PAR-1/MARK kinase was shown to be a positive regulator of MT-dependent transportation in the axons of RGC neurons (40) but a negative regulator of the cortical actin network via association with PAK5 (41). Local destabilization of F-actin may be a trigger for axonal specification (10). Interestingly, during epithelial polarization, reduced MARK2 levels are associated with weaker peripheral F-actin staining (20), raising an intriguing possibility that MARK2-siRNA-induced formation of multiple axons might be caused by local actin dynamics. The mechanisms that coordinate MT and actin cytoskeleton assembly and dynamics remain to be clarified.

Methods

Reagents, Antibodies, and Constructs.

The antibodies used for immunostaining or immunoblotting were from Chemicon (MAP2, Tau1, and synapsin), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (PKCζ), BioSource International [p-tau (S262)], Calbiochem (tau), and Sigma (β-tubulin III). Rabbit anti-MARK2 antibody was generated by immunization with GST-hMARK2 (amino acids 531–670) as an antigen. Rabbit anti-p-MARK2 at T595 was reported in ref. 26. Double-stranded oligonucleotides targeting against MARK2 were synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The siRNA sequence was designed against a region starting from nucleotide 1180 or 1677 of rat MARK2 cDNA. The sequence from nucleotide 1677 is 5′-GAATGAACCTGAAAGCAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTGCTTTCAGGTTCATTC-3′ (reverse). The sequence from nucleotide 1180 is 5′-CAGAGTAACAACGCAGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTCTGCGTTGTTACTCTG-3′ (reverse). SAD plasmids were kindly provided by J. R. Sanes (Harvard University, Boston). EGFP-tau plasmids were gifts from K. S. Kosik (Harvard Medical School, Boston). PAR-3 and PAR-6 were gifts from I. G. Macara (University of Virginia, Charlottesville) (30). Flag-PKCζ and PAR-1b/MARK2 (wild type and T595A mutant) constructs were introduced in ref. 26. MARK2 fragments were subcloned inframe into BglII and KpnI sites of pEGFP-N1. aPKC-N (amino acids 1–109) was subcloned into BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pKH3 vector.

Neuron Culture and Electroporation.

Hippocampi of embryonic day-17 rat embryos were digested with 0.125% trypsin/EDTA for 20 min at 37°C, followed by trituration with pipettes in the plating medium (DMEM with 10% FBS). Dissociated neurons were transfected by using a nucleofector device (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). In some experiments, testing plasmids were cotransfected with pEGFP with a ratio of 3:1. Control and transfected neurons were plated onto coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (0.1 mg/ml) and laminin (0.05 mg/ml). After culturing for 4 h, media were changed into neuronal culture medium (neurobasal media containing 1% glutamate and 2% B27).

Immunohistochemistry.

Neurons were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 45 min, and incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. After blocking with 10% goat serum in PBS at room temperature for 1 h or at 4°C overnight, neurons were incubated in primary antibodies at 4°C for 12 h and subsequently with Alexa Fluor 350-, FITC-, or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted and examined by using a Neurolucida system (Nikon).

Biochemical Characterization.

Rat brains were homogenized in cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors. After clarification by centrifugation (100,000 × g; 1 h at 4°C), lysates were immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. HEK-293 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected with the standard calcium phosphate method. Cell lysates were prepared in the cold lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as described in ref. 42.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. J. R. Sanes for discussion and SAD constructs, Dr. I. Macara for PAR-3 and PAR-6 constructs, Dr. K. S. Kosik for tau constructs, Dr. G. Banker for discussions, Dr. L. Mei for the critical reading of and comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Q. Hu for the assistance in imaging. This work was supported in part by a National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 90408026 (to Z.G.L.), Shanghai Science and Technology Development Foundation Grant 03JC14078 (to Z.G.L.), and the National Institutes of Health (H.P.-W.). H.P.-W. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- MAP

microtubule-associated protein

- MT

microtubule

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- aPKC

atypical PKC

- PAR

partitioning-defective protein

- MARK

microtubule affinity-regulating kinase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- DIVn

n days in vitro

- aPKC-N

amino-terminal PB1 domain of aPKC.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Dotti C. G., Sullivan C. A., Banker G. A. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:1454–1468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01454.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig A. M., Banker G. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1994;17:267–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arimura N., Menager C., Fukata Y., Kaibuchi K. J. Neurobiol. 2004;58:34–47. doi: 10.1002/neu.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandell J. W., Banker G. A. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5727–5740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05727.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matus A., Bernhardt R., Hugh-Jones T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder L. I., Frankfurter A., Rebhun L. I. J. Cell Biol. 1985;101:1371–1378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baas P. W. Neuron. 1999;22:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiggin G. R., Fawcett J. P., Pawson T. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:803–816. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton A. C., Ehlers M. D. Neuron. 2003;40:277–295. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradke F., Dotti C. G. Science. 1999;283:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takei Y., Teng J., Harada A., Hirokawa N. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:989–1000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimura T., Kawano Y., Arimura N., Kawabata S., Kikuchi A., Kaibuchi K. Cell. 2005;120:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H., Guo W., Liang X., Rao Y. Cell. 2005;120:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi S. H., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. Cell. 2003;112:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura T., Kato K., Yamaguchi T., Fukata Y., Ohno S., Kaibuchi K. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:328–334. doi: 10.1038/ncb1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwamborn J. C., Puschel A. W. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:923–929. doi: 10.1038/nn1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolls M. M., Doe C. Q. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1293–1295. doi: 10.1038/nn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura T., Yamaguchi T., Kato K., Yoshizawa M., Nabeshima Y., Ohno S., Hoshino M., Kaibuchi K. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:270–277. doi: 10.1038/ncb1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohm H., Brinkmann V., Drab M., Henske A., Kurzchalia T. V. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A., Hirata M., Kamimura K., Maniwa R., Yamanaka T., Mizuno K., Kishikawa M., Hirose H., Amano Y., Izumi N., et al. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drewes G., Ebneth A., Preuss U., Mandelkow E. M., Mandelkow E. Cell. 1997;89:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drewes G. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biernat J., Wu Y. Z., Timm T., Zheng-Fischhofer Q., Mandelkow E., Meijer L., Mandelkow E. M. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:4013–4028. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-03-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher T. L., Cameron P., De Camilli P., Banker G. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:1617–1626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01617.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaar B. T., Kinoshita K., McConnell S. K. Neuron. 2004;41:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurov J. B., Watkins J. L., Piwnica-Worms H. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusakabe M., Nishida E. EMBO J. 2004;23:4190–4201. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishi M., Pan Y. A., Crump J. G., Sanes J. R. Science. 2005;307:929–932. doi: 10.1126/science.1107403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inglis J. D., Lee M., Hill R. E. Mamm. Genome. 1993;4:401–403. doi: 10.1007/BF00360595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joberty G., Petersen C., Gao L., Macara I. G. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin D., Edwards A. S., Fawcett J. P., Mbamalu G., Scott J. D., Pawson T. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:540–547. doi: 10.1038/35019582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura I., Yang Y., Lu B. Cell. 2004;116:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biernat J., Gustke N., Drewes G., Mandelkow E. M., Mandelkow E. Neuron. 1993;11:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi S. H., Cheng T., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:2025–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goold R. G., Owen R., Gordon-Weeks P. R. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:3373–3384. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.19.3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas F. R., Goold R. G., Gordon-Weeks P. R., Salinas P. C. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1351–1361. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanger D. P., Hughes K., Woodgett J. R., Brion J. P., Anderton B. H. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;147:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zumbrunn J., Kinoshita K., Hyman A. A., Nathke I. S. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosuga S., Tashiro E., Kajioka T., Ueki M., Shimizu Y., Imoto M. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42715–42722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandelkow E. M., Thies E., Trinczek B., Biernat J., Mandelkow E. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:99–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matenia D., Griesshaber B., Li X. Y., Thiessen A., Johne C., Jiao J., Mandelkow E., Mandelkow E. M. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4410–4422. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo Z. G., Wang Q., Zhou J. Z., Wang J., Luo Z., Liu M., He X., Wynshaw-Boris A., Xiong W. C., Lu B., Mei L. Neuron. 2002;35:489–505. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.