Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 can trigger cell death independently of its transcriptional activity through subcellular translocation and activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. The regulation of such activity of endogenous p53 in response to stress remains largely unknown. Here we show that nuclear, activated FOXO3a could impair p53 transcriptional activity. However, activation of FOXO3a either on serum starvation or by expressing a constitutively active form of FOXO3a could induce p53-dependent apoptosis, even in cells bearing a transcriptionally inactive form of p53. Furthermore, FOXO3a could promote p53 cytoplasmic accumulation by increasing its association with nuclear exporting machinery. Our data also suggest that PUMA and Bax are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in manner that is independent of p53 transcriptional activity.

Keywords: apoptosis

Members of mammalian FOXO family of forkhead transcription factors are critical positive regulators of longevity in species as diverse as worms and flies (1–3). Regulation of resistance to cellular oxidative stress has been suggested as the mechanism by which FOXO factors exert their antiaging function (4). However, FOXO factors can also play a proapoptotic role in neurons or hematopoietic cells subjected to growth factor or cytokine withdrawal. In this situation, the survival kinase AKT is inactive, and FOXO remains in the nucleus where it induces p27 and possibly other unidentified downstream targets to induce apoptosis (5, 6). It is clear that transcriptional regulation of multiple downstream targets plays important roles in proapoptotic or antiapoptotic function of FOXO. However, the way in which FOXO communicates and coordinates with other proapoptotic or antiapoptotic signaling pathways in response to genotoxic stress remains largely unexplored. In this report, we demonstrate that nuclear, activated FOXO3a (one of the FOXO family members) can inhibit the activation of p53 by DNA damage. Paradoxically, FOXO3a can trigger p53-dependent cell death, and the transcriptional activity of p53 is dispensable for such forms of apoptosis. Our results suggest that FOXO3a could regulate p53 subcellular localization, which in turn induces cell death through PUMA–Bax axis.

Results

Activation of FOXO3a Induces p53-Dependent Apoptosis.

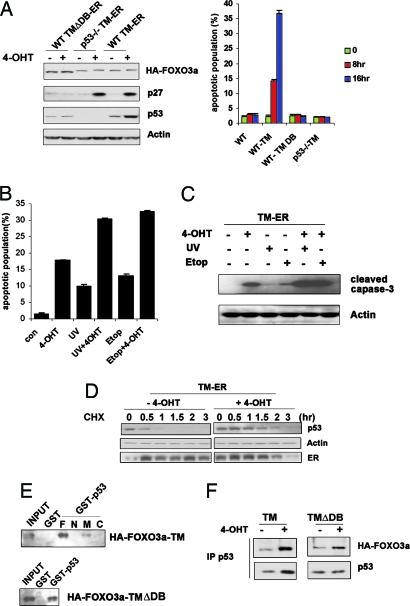

Genotoxic stress triggers p53 to induce expression of SGK1 protein kinase, which in turn phosphorylates FOXO3a and causes it to translocate out of the nucleus (7). To determine what would happen to p53 activity if FOXO3a remained in the nucleus, we established inducible mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell lines (in both p53+/+ and p53−/− genetic backgrounds) bearing one of two different estrogen receptor (ER) fusion constructs: hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged FOXO3a-triple mutant (TM)-ER (TM-ER) or HA-tagged FOXO3a-TMΔDB-ER (TMΔDB-ER). TM is a triple mutant form of FOXO3a in which all three Akt phosphorylation sites are mutated to alanine (FOXO3a-TM, T32A/S253A/S315A). Upon engagement of ER by 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), the TM-ER construct is expressed as a constitutively active form of FOXO3a that is trapped in the nucleus. TMΔDB-ER is a form of TM-ER protein that lacks the FOXO3a DNA binding domain (DB), and so cannot bind the promoter regions of FOXO3a target genes (serves as a negative control). As expected, WT MEFs expressing TM-ER showed an induction of p27 on the addition of 4-OHT that was not observed in WT TMΔDB-ER cells (Fig. 1A Left). Interestingly, even in the absence of DNA damage, TM-ER expression in WT MEFs triggered substantial cell death by 8 h after 4-OHT addition, but no apoptosis was observed in 4-OHT-treated p53−/− TM-ER cells (Fig. 1A Right). Thus, FOXO3a-induced apoptosis is p53-dependent. Induction of TMΔDB-ER in WT MEFs failed to induce any apoptosis, indicating that the DNA binding domain of FOXO3a is essential for cell death under these circumstances. Furthermore, when genotoxic stress in the form of UV or etoposide (Etop) was applied simultaneously with TM-ER induction, the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis increased significantly (Fig. 1B). The additional activation of apoptotic program in these cells induced by FOXO3a-TM plus DNA damage was confirmed by examination of caspase-3 cleavage (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Regulation of p53 protein stability and p53-dependent apoptosis by FOXO3a. Nuclear, activated FOXO3a induces p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence (A) or presence (B) of DNA damage. (A Left) Western blot of lysates of cells exposed to 4-OHT for 6 h probed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. (A Right) WT, WT TMΔDB–ER, p53−/− TM-ER, and WT TM-ER MEFs were exposed to 4-OHT (0.5 μM) for 8 or 16 h. Percentages of apoptotic cells in the cultures were determined by flow cytometry. (B) WT TM-ER cells were left untreated or treated with UV (30J/m2) or Etop (0.5 μM) in the presence or absence of 4-OHT (0.5 μM) for 8 h. Percentages of apoptotic cells were determined as in A. (C) Confirmation of apoptosis by caspase-3 cleavage. WT TM-ER cells were treated as in B and the cleavage of caspase-3 in cell lysates was examined by Western blotting. (D) FOXO3a-TM stabilizes steady-state levels of endogenous p53 protein. WT MEFs expressing TM-ER were left untreated or treated with 0.5 μM 4-OHT along with cycloheximide (CHX; 40 μg/ml) for indicated time points. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting. (E and F) In vitro and in vivo interaction between p53 and FOXO3a. (E) The p53 DNA binding domain is required for in vitro interaction with FOXO3a. (F) GST or GST-full-length p53, the p53 N terminus (N), the p53 middle region (M), or the p53 C terminus (C) was incubated with in vitro-translated HA-FOXO3a-TM or HA-FOXO3a-TMΔDB. Bound FOXO3a was detected by anti-HA immunoblotting. Both FOXO3a-TM and TMΔDB were able to interact with endogenous p53. (F) In vivo association of p53 and FOXO3a. WT MEFs expressing TM-ER or TMΔDB-ER were left untreated or treated with 4-OHT for 8 h. Immunoprecipitates obtained by using anti-p53 Ab were immunoblotted with anti-HA and anti-p53 Abs as indicated.

Stabilization of p53 by Nuclear, Activated FOXO3a.

The requirement of p53 for FOXO3a-induced apoptosis implied that there might be a functional interaction between these two transcription factors. To explore this possibility, we determined p53 protein levels as well as p53 transcriptional activity in WT TM-ER and WT TMΔDB-ER cells. Upon addition of 4-OHT, p53 protein was markedly increased in TM-ER cells but not in TMΔDB-ER cells (Fig. 1A Left). However, using quantitative real-time PCR, we determined that this difference was not because of regulation of p53 gene transcription by FOXO3a (data not shown). Rather, we found that TM-ER activation extended the half-life of p53 from its usual 20 min (under physiological conditions) to ≈90 min (Fig. 1D). Because FOXO3a has been shown to bind p53 (8), we then investigated whether protein-protein interaction was involved in TM-induced p53 stabilization. However, both TM and TMΔDB interacted equally well with both GST-p53 and endogenous p53 (Fig. 1 E and F, respectively), indicating that physical interaction between p53 and FOXO3a is not required for FOXO3a-induced p53 stabilization.

FOXO3a Inhibits p53 Transcriptional Activity.

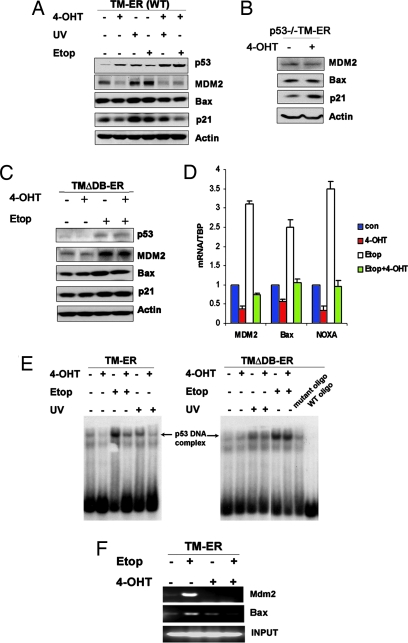

We had expected that increased p53 stability would result in enhanced p53 transcriptional activity, but, surprisingly, the p53 downstream target genes MDM2, Bax, and p21 were not induced after 4-OHT addition to the WT TM-ER cells (Fig. 2A). Protein levels of these downstream targets were slightly decreased upon TM-ER induction. To rule out the possibility that these reductions were because of direct transcriptional repression by FOXO3a (rather than p53-dependent regulation), we analyzed MDM2, Bax, and p21 expression in p53−/− TM-ER MEFs. Induction of TM-ER in the absence of p53 had no impact on the expression of MDM2 and Bax (Fig. 2B), but p21 levels were slightly elevated. This latter result is consistent with a recent report that p21 is a direct downstream target of FOXO (9).

Fig. 2.

Activation of FOXO3a-TM inhibits p53 transcriptional activity. (A) Inhibition of p53-induced target protein expression. WT TM-ER cells were treated for 8 h with 4-OHT (0.5 μM), UV (30J/m2), or Etop (0.5 μM) alone, or in the indicated combinations. Western blotting was performed to assess protein levels of p53 and its downstream targets, MDM2, Bax, and p21. (B and C) p53−/− TM-ER MEF cells (B), as well as WT TMΔDB–ER MEFs (C), were treated with 4-OHT (0.5 μM) or Etop (0.5 μM) alone, or treated with Etop along with 4-OHT for 8 h. Western blotting was performed for antibodies as indicated. (D) Inhibition of p53 target gene mRNA expression. WT TM-ER MEFs were treated as in A, and total RNA was extracted. Levels of mdm2, bax, and noxa mRNA were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to control TBP mRNA. (E and F) Inhibition of p53 DNA binding activity. (E) Gel shift assays were performed by using nuclear extracts from WT TM-ER or TMΔDB-ER cells treated as in A. p53-DNA complex formation was visualized by autoradiography. (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to detect association between p53 and mdm2 or bax promoter were performed as described in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, by using WT TM-ER MEFs treated as indicated for 8 h. DNA from input samples was amplified for normalization. Results shown are one trial representative of three independent experiments.

We next determined whether FOXO3a-TM could affect p53 transcriptional activity in the presence of DNA damage. Upon adding 4-OHT, p53 activation in response to DNA damage signals was inhibited. Western blotting showed that the inductions of MDM2, p21, and Bax in response to UV or Etop treatment were all decreased upon activation of TM-ER (Fig. 2A) but not after the activation of TMΔDB-ER (Fig. 2C). These results were confirmed and extended for WT TM-ER MEFs by using quantitative real-time PCR to analyze mdm2, bax, and noxa mRNA expression (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data indicate that constitutively active FOXO3a impairs p53 transcriptional activity. Moreover, TM-induced p53 protein stabilization might be partly because of the attenuated MDM2 mediated-ubiquitination via the decreased expression of MDM2 that resulted from impaired p53 transactivation.

To investigate whether the observed reduction in p53 transcriptional activity was because of a decrease in its DNA binding capacity, we performed both gel shift and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. Nuclear extracts were prepared from WT TM-ER or TMΔDB-ER MEFs that had been left untreated or treated with either UV or Etop, in the presence or absence of 4-OHT. The binding of p53 in these extracts to a DNA fragment containing a consensus p53-binding element was then analyzed by gel shift assay. p53-DNA complex formation was significantly decreased in TM-ER, but not in TMΔDB-ER, cells when 4-OHT was added to the culture (Fig. 2E), demonstrating that the TM form of FOXO3a is able to prevent p53 from binding to the p53-binding element in vitro. To examine p53-DNA binding in vivo, we performed ChIP assays by using primers flanking the p53 binding sites in the promoter regions of mdm2 and bax genes. Consistent with the gel shift results, the ChIP assays showed that FOXO3a-TM activation reduced the association of p53 with the endogenous mdm2 or bax promoters on Etop treatment (Fig. 2F). Thus, the in vivo DNA binding activity of p53 is inhibited by FOXO3a-TM, even in the presence of DNA damage signals.

FOXO3a-Induced Apoptosis Requires PUMA and Bax.

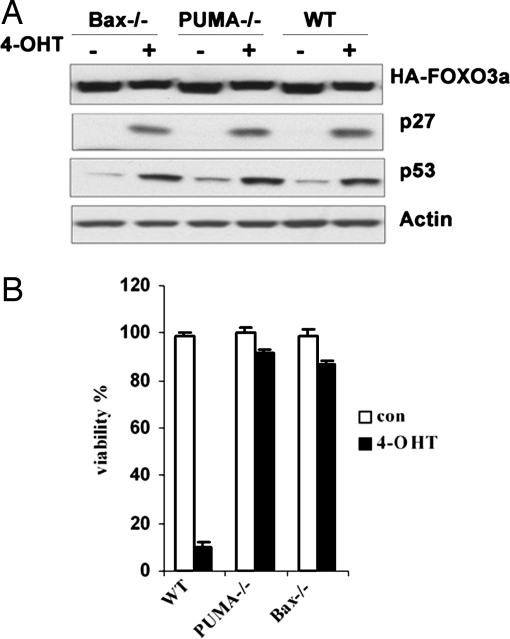

When we tested p53 downstream targets levels in TM-ER cells, all chosen targets were down-regulated upon TM-ER induction detected by RT-PCR and further confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR, except PUMA (data not shown). A previous report found that a broader range of apoptotic stimuli could regulate PUMA expression, including cell death pathways that are mediated independent of p53 transcription activity. For example, serum deprivation could induce PUMA mRNA level in tumor cells bearing mutant p53, but the relevant downstream transcription factors involved remain unknown (10). We found that FOXO3a could regulate PUMA at transcriptional level independent of p53 (H.Y., K.Y., and T.W.M., unpublished data). BH3-only proteins have been shown to mediate apoptosis through different mechanisms. PUMA could act through interacting with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 members, which in turn liberates other BH3 proteins that can activate Bax or Bak (11–15). To determine the role of PUMA in FOXO3a-induced cell death, we constructed PUMA−/− TM-ER stable MEF cell line (Fig. 3A). Intriguingly, deletion of PUMA almost completely abolished TM-ER-induced cell death (Fig. 3B), indicating that PUMA is essential for FOXO3a-induced cell death. We also explored the role of Bax because it has been shown as one of the critical executers in PUMA-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis (11, 16). Likewise, Bax−/− TM-ER MEFs conferred large resistance to TM activation-induced cell death (Fig. 3B), suggesting that Bax is required to mediate FOXO3a-induced cell death.

Fig. 3.

FOXO3a-dependent apoptosis requires PUMA and Bax. (A) Confirmation of comparable FOXO3a-TM expression and activity in WT TM-ER, PUMA−/− TM-ER, and Bax−/− TM-ER cells. MEFs were left untreated or treated with 4-OHT for 6 h, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting to detect FOXO3a, p27, and p53. (B) WT TM-ER, PUMA−/− TM-ER, and Bax−/− TM-ER MEFs were left untreated (con) or treated with 4-OHT for 24 h. The percentage of viable cells was determined by flow cytometry.

Activation of FOXO3a Induces Apoptosis in p53QSA135V Cells.

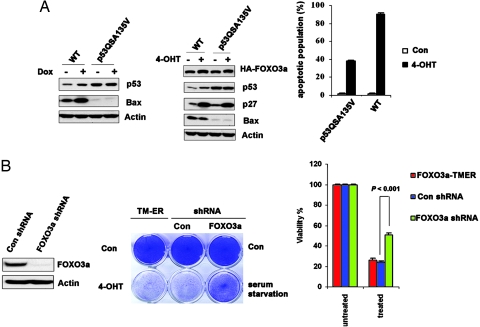

Recently, p53 has been shown to activate Bax upon cytosolic localization, which allows for mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis (17, 18). Although activation of FOXO3a-TM led to inhibition of p53 transcriptional activity, but p53 was still required for FOXO3a-TM-induced apoptosis, we hypothesized that it might be cytoplasmic proapoptotic activity, rather than nuclear transcriptional activity of p53, that mediated active FOXO3a-induced apoptosis through PUMA–Bax axis. To test this possibility, we first examined whether TM could induce cell death in cells bearing transactivation incompetent p53. p53QSA135V is a transcriptionally inactive form of p53 that contained two tandem mutations L25Q and W26S in the transcription domain and a point mutation, A135V, in the DNA binding domain (19, 20). Using quantitative real-time PCR, we found the basal expression levels of p53 downstream target genes: mdm2, bax, p21, and puma in p53QSA135V cells were similar to their levels in p53 deficient MEFs (data not shown). Importantly, this mutant p53 failed to induce p53 downstream targets (for example, Bax) in response to genotoxic treatment (Fig. 4A Left). We also confirmed that it was incapable of inducing p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage, as reported in refs. 19 and 20. We constructed a p53QSA135V FOXO3a-TM-ER stable MEF cell line and confirmed that expression levels of FOXO3a-TM, as well as its transcriptional activity, were comparable in WT TM-ER MEFs and p53QSA135V TM-ER cells (Fig. 4A Center). Intriguingly, activation of FOXO3a-TM alone induced apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells, although to a lesser extent compared with cell death in WT TM-ER cells (Fig. 4A Right), suggesting basal transcriptional activity of WT p53 could sensitize cells to FOXO3a-TM-induced apoptosis (the basal mRNA levels of puma and bax in p53QSA135V MEFs are ≈25% of those in WT MEFs; data not shown). Importantly, TM activation in p53QSA135V cells induced the same extent of cell death, compared with p53QSA135V cells expressing control shRNA exposed to serum-free medium (Fig. 4B Center), indicating FOXO3a-TM expression levels in these cells recapitulate serum deprivation-induced activation of the endogenous protein. Furthermore, ablation of endogenous FOXO3a by shRNA knockdown (Fig. 4B Left) significantly rescued serum starvation-triggered apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells (Fig. 4B Center and Right). These data demonstrate that activation of FOXO3a, either by serum deprivation or by ectopic expression of a constitutively active form of this molecule, induces cell death in cells harboring transcriptionally inactive p53. Because p53−/− MEFs are resistant to apoptosis triggered by either serum withdrawal (ref. 20 and data not shown) or FOXO3a-TM activation (Fig. 1A Right), WT p53 or p53QSA135Vprotein must be required for these forms of cell death. Taken together, our data strongly indicate that activated FOXO3a and p53 may functionally interact to determine cell fate under stress conditions such as serum starvation.

Fig. 4.

FOXO3a activation promotes cell death in p53QSA135V cells. (A) FOXO3a-TM induces apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells. (A Left) WT and p53QSA135V MEFs were treated with doxorubicin (0.2 μg/ml) for 8 h. Western blotting was used to detect p53 and Bax. (A Center) Cell lysates from WT TM-ER and p53QSA135V TM-ER cells were subjected to Western blotting. (A Right) WT TM-ER and p53QSA135V TM-ER MEFs were treated with 4-OHT (0.5 μM) for 24 h and analyzed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Results shown are the mean ± SD of duplicate samples and are representative of three independent experiments. (B) FOXO3a is required for serum starvation-induced apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells. (B Left) Western blot showing that FOXO3a shRNA successfully blocked FOXO3a expression. (B Center) Left column, crystal violet staining to detect apoptosis in cultures of p53QSA135V TM-ER cells that were left untreated (con) or treated with 4-OHT for 48 h; center column, serum starvation (48 h) induced apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells expressing control shRNA; right column, shRNA knockdown of FOXO3a prevents serum starvation-induced cell death in p53QSA135V cells. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B Right) Quantification of results from Center. Untreated, cells grow in medium containing 10%FBS; treated, cells were exposed to serum starvation. The difference of cell death induced by serum starvation between control shRNA and FOXO3a-shRNA MEFs is statistically significant (P<0.001, t test).

Subcellular Localization Change of p53 upon Activation of FOXO3a.

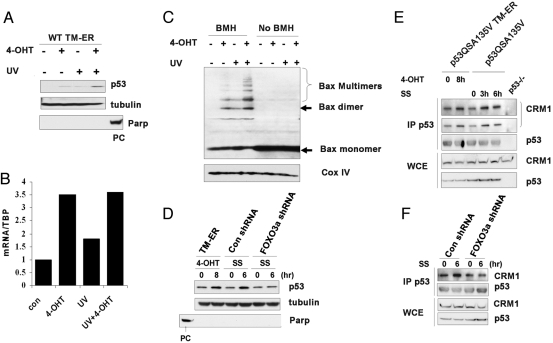

Endogenous p53 has been shown to induce apoptosis in the presence of a nuclear import inhibitor, suggesting cytosolic p53 may retain some proapoptotic activity even when its nuclear activity is impaired (17). To determine how p53 is regulated by FOXO3a during FOXO3a-triggered apoptosis, we first examined WT p53 subcellular localization in response to TM-ER activation. Upon addition of 4-OHT, cytosolic p53 accumulation was observed in WT TM-ER cells (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, cytosolic p53 levels correlated with Bax oligomerization status. TM activation, along with UV damage, induced more cytosolic p53 accumulation compared with TM activation alone, and the upregulation of cytosolic p53 correlated with increased Bax oligomerization even when PUMA induction was achieved to the same levels (Fig. 5 B and C), indicating cytosolic p53 might have the potential to activate Bax, as suggested by others (17, 21). Because FOXO3a-TM activation also increased p53 protein stability in WT cells (Fig. 2A), the increase in cytosolic p53 in WT TM-ER cells then might be because of changes in the total protein level. To further confirm the role of FOXO3a in inducing p53 accumulation in cytosol, we performed cytosolic fractionation to detect p53 levels in p53QSA135V TM-ER cells before and after the addition of 4-OHT, or in p53QSA135V MEFs before and after serum starvation. Consistent with ref. 19, we found that p53QSA135V protein displayed heterogeneous distribution under untreated conditions. Although a large portion of p53 localized in the nucleus (data not shown), a small percentage of cytoplasmic p53 proteins were also observed. Activation of TM-ER or serum withdrawal significantly increased cytosolic p53 levels in S-100 fraction (Fig. 5D) without affecting total p53 protein expression (Fig. 4A Center). Cytosolic p53 accumulation was also detected when p53QSA135V cells expressing control shRNA were deprived of serum for 6 h (Fig. 5D). This translocation of p53 was impaired when endogenous FOXO3a was ablated by shRNA knockdown. Taken together, our results suggest that activation of FOXO3a, either by serum starvation or expressing TM mutant, can drive changes in p53 subcellular localization.

Fig. 5.

FOXO3a activation drives p53 cytoplasmic localization in p53QSA135V cells. (A) FOXO3a-TM activation induces accumulation of p53 in the cytosol. WT TM-ER MEFs were treated with UV in the presence or absence of 4-OHT for 6 h. S-100 fractions were subjected to Western blotting by using antibodies against p53 and tubulin (cytosolic fraction indicator). Nuclear protein poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (Parp) was used to control the purity of cytosolic fractions (PC, positive control). (B) WT TM-ER cells were treated as in A. PUMA expression levels were detected by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) Activation of TM induces Bax oligomerization at the mitochondrial. WT TM-ER cells were treated as in A. Mitochondrial fractions were extracted as described in ref. 39 and were subjected to Western blotting. COX IV was used for loading control. (D) p53QSA135V MEFs expressing TM-ER, control shRNA, or FOXO3a-shRNA were treated as indicated. Western blotting was performed by using S-100 fraction. Parp was used to monitor cytoplasm fraction contamination (PC, positive control). (E) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of p53 followed by Western blot analysis for associated nuclear export receptor CRM1 in p53QSA135V TM-ER MEFs or p53QSA135V MEFs treated as indicated. CRM1 was presented by using different exposure time (top panel, longer exposure; second panel from top, shorter exposure). p53 and CRM1 levels were also detected by Western blotting in whole cell extracts (WCE). (F) p53QSA135V MEFs expressing control shRNA or FOXO3a shRNA were serum starved for 6 h; IP was conducted as in E. CRM1 and p53 levels in either immune complexes or WCE were detected by using specific antibodies by Western blotting.

The enhanced cytoplasmic localization of p53 protein in p53QSA135V MEFs in response to activation of FOXO3a suggested that greater nuclear export of p53 might occur under these conditions. We hypothesized that p53 protein might be more efficiently associated with the key nuclear-export receptor CRM1 upon activation of FOXO3a. Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis by using cell lysates from p53QSA135V TM-ER or p53QSA135V MEFs indicated that there was increased association of CRM1 with p53 when 4-OHT or serum deprivation was applied (Fig. 5E). Intriguingly, knockdown of FOXO3a significantly impaired CRM1-p53 interaction after serum withdrawal (Fig. 5F), suggesting a critical role of FOXO3a in mediating p53 nuclear-cytoplasm shuttling. Posttranslational modifications of p53, for instance, ubiquitination of p53 by MDM2, have been reported to contribute to p53 nuclear export (22–24). However, the nuclear export signal (NES) of p53 itself is capable of mediating cytoplasmic localization of p53 in MDM2-independent manner (25). Because p53QSA135V is defective in MDM2 binding (19), the increased nuclear-cytoplasm shuttling of p53 in response to FOXO3a activation might be independent of MDM2 (see Discussion).

Discussion

p53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancers (26, 27). The tumor suppressor function of p53 has been viewed exclusively as a transcription factor that conducts its many functions by transactivating downstream targets involved in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. Thus, p53 protein carrying loss-of-function mutations has been considered as “dead” p53 in chemotherapy, because these mutants confer resistance to anticancer reagents.

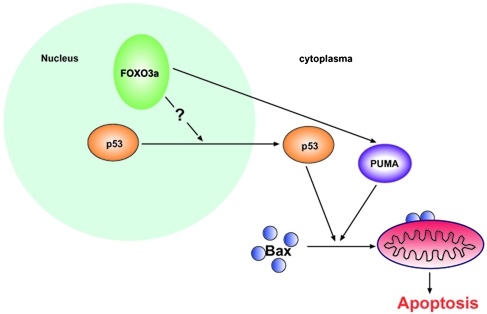

During the past decades, several groups reported transcription independent proapoptotic activity of p53. The proposed mechanisms include that p53 can function at the mitochondrial (28, 29) or that p53 can act as a BH3 protein to induce Bax activation if forced to translocate into cytoplasm by pharmacological inhibitors (17). Here, our data presented a model that activation of FOXO transcription factor could regulate the transactivation-independent proapoptotic activity of endogenous p53 (Fig. 6). Ectopic expressing active form of FOXO3a has negative effect on nuclear p53 activation, even in the presence of DNA damage signals. Paradoxically, FOXO3a is still able to induce apoptosis in p53-dependent manner. To explore which activity of p53 contributes to FOXO3a-triggered cell death, we took advantage of a transactivation incompetent mutant form of p53: p53QSA135V. A human p53 mutant carrying the same mutations in residues 22 and 23 has been shown to trigger apoptosis upon overexpression, despite failing to induce significant activation of relevant p53 target promoters (30). Interestingly, in our system, activation of exogenously expressed FOXO3a induced apoptosis in p53QSA135V MEF cells. Furthermore, in p53QSA135V MEFs, constitutively active FOXO3a could mimic serum starvation-induced FOXO3a activation in inducing apoptosis, indicating that the gene dosage of exogenously expressed FOXO3a could recapitulate activation of endogenous FOXO3a under physiological conditions.

Fig. 6.

Model of apoptosis induced by nuclear activated FOXO3a and mediated by cytosolic p53 and PUMA–Bax axis.

The pathway by which p53 regulates serum starvation response has not been well characterized. Our finding that p53QSA135V retains partial apoptotic activity under conditions of serum starvation, whereas p53 null cells confer resistance to such stress, suggests that a transactivation-independent activity of p53 is required to induce cell death in this situation. Acute loss of FOXO3a by shRNA knockdown significantly rescued apoptosis in p53QSA135V cells, indicating that crosstalk between the endogenous FOXO3a and p53QSA135V proteins may determine cell fate under such stress conditions. Moreover, we investigated the mechanism by which activated FOXO3a (present either as a result of the TM mutation or serum starvation) might regulate p53, and we found that FOXO3a induced changes to p53’s subcellular localization. Importantly, the impairment of cytosolic p53 localization in p53QSA135V cells that occurred upon FOXO3a shRNA knockdown correlated with the decrease in cell death observed after serum deprivation. We also performed serum starvation by using WT MEFs to see whether activation of endogenous FOXO3a could mimic FOXO3a-TM in regulating WT p53. Surprisingly, serum withdrawal led to significant stabilization of p53, which subsequently induced apoptosis (H.Y. and T.W.M., unpublished data). Our preliminary data suggest posttranslational modifications of p53 may play an important role in p53 stabilization after serum deprivation. Taken together, it is likely that both transactivation-dependent and transactivation-independent activities of p53 are involved in regulating serum starvation response. Our results provided evidence that FOXO3a could regulate the latter activity of p53 through subcellular localization change-mediated pathway.

How does FOXO3a regulate p53 subcellular translocation? A highly conserved leucine-rich NES has been identified in the tetramerization domain of p53. This intrinsic NES is both necessary and sufficient to direct p53 nuclear export (25). Interestingly, under conditions when FOXO3a was activated by 4-OHT or serum starvation, we found an increased association between p53 protein and the nuclear-export receptor CRM1. Tetramerization of p53 has been proposed as a potential mechanism leading to p53 nuclear accumulation and activation by masking the NES and preventing access to the nuclear export machinery (31–33). Furthermore, it is well known that tetrameric p53 binds its DNA response elements most efficiently and is most effective for transactivation (34–38). Thus, we hypothesize that activation of FOXO3a may interfere with p53 oligomerization, which in turn unmasks p53 NES, and results in increased nuclear export, as well as impairment of p53 DNA binding and transactivation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

p53QSA135V primary MEF cells were provided by Geoffrey Wahl (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA). Primary PUMA−/− MEFs were the generous gift of Andreas Strasser (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia). Bax−/− MEFs were the kind gift of Doug Green (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). All primary MEFs were transformed by E1A/ras G12V, followed by puromycin selection. For FOXO3a-related stable cell lines, MEFs were cotransfected with pECE HA-FOXO3a (TM or DB) and a GFP plasmid in 15:1 ratio. Cells were selected by GFP sorting after 48 h, and positive cells were pooled together for use in experiments.

RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and purified by using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with the addition of on-column DNase treatment (Qiagen). RNA (4 μg) was reverse-transcribed in a 20-μl reaction by using the Superscript first strand RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). After RNase H treatment at 37°C for 20 min, followed by inactivation at 95°C for 2 min, the real-time reaction was diluted. cDNA was used for RT-PCR or real-time PCR. Primer sequences were as follows: Noxa, 5′-CCACCTGAGTTCGCAGCTCAA and 5′-GTTGAGCACACTCGTCCTTCAA; and p27, 5′-TCAAACGTGAGAGTGTCTAACGG and 5′-AGGGGCTTATGATTCTGAAAGTCG. MDM2, p21, and Bax primers were from ref. 17.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Levine (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), M. Greenberg (Harvard Medical School, Boston), S. Lowe (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY), G. Wahl (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA), D. Green (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN), B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore), A. Strasser (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne), W. Gu (Columbia University, New York), and H. Lu (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR) for reagents; K. Vousden (The Beatson Institute, Glasgow, U.K.) and S. Benchimol (University of Toronto, Toronto) for critical discussions; and M. Saunders for scientific editing. This work was supported by the Terry Fox Cancer Foundation of the National Cancer Institute of Canada. H.Y. is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute (New York).

Abbreviations

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- ER

estrogen receptor

- Etop

etoposide

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- NES

nuclear export signal

- TM

triple mutant.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Lin K., Hsin H., Libina N., Kenyon C. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:139–145. doi: 10.1038/88850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwangbo D. S., Gersham B., Tu M. P., Palmer M., Tatar M. Nature. 2004;429:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannakou M. E., Goss M., Junger M. A., Hafen E., Leevers S. J., Partridge L. Science. 2004;305:361. doi: 10.1126/science.1098219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemoto S., Finkel T. Science. 2002;295:2450–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stahl M., Dijkers P. F., Kops G. J., Lens S. M., Coffer P. J., Burgering B. M., Medema R. H. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5024–5031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilley J., Coffer P. J., Ham J. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:613–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.You H., Jang Y., You-Ten A. I., Okada H., Liepa J., Wakeham A., Zaugg K., Mak T. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14057–14062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406286101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunet A., Sweeney L. B., Sturgill J. F., Chua K. F., Greer P. L., Lin Y., Tran H., Ross S. E., Mostoslavsky R., Cohen H. Y., et al. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seoane J., Le H. V., Shen L., Anderson S. A., Massague J. Cell. 2004;117:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han J., Flemington C., Houghton A. B., Gu Z., Zambetti G. P., Lutz R. J., Zhu L., Chittenden T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11318–11323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201208798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu J., Wang Z., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Zhang L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J., Zhang L., Hwang P. M., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano K., Vousden K. H. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng E. H., Wei M. C., Weiler S., Flavell R. A., Mak T. W., Lindsten T., Korsmeyer S. J. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:705–711. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korsmeyer S. J., Wei M. C., Saito M., Weiler S., Oh K. J., Schlesinger P. H. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1166–1173. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melino G., Bernassola F., Ranalli M., Yee K., Zong W. X., Corazzari M., Knight R. A., Green D. R., Thompson C., Vousden K. H. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8076–8083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chipuk J. E., Kuwana T., Bouchier-Hayes L., Droin N. M., Newmeyer D. D., Schuler M., Green D. R. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chipuk J. E., Bouchier-Hayes L., Kuwana T., Newmeyer D. D., Green D. R. Science. 2005;309:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez G. S., Nister M., Stommel J. M., Beeche M., Barcarse E. A., Zhang X. Q., O’Gorman S., Wahl G. M. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:37–43. doi: 10.1038/79152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson T. M., Hammond E. M., Giaccia A., Attardi L. D. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:145–152. doi: 10.1038/ng1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erster S., Mihara M., Kim R. H., Petrenko O., Moll U. M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:6728–6741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6728-6741.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottifredi V., Prives C. Science. 2001;292:1851–1852. doi: 10.1126/science.1062238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dumont P., Leu J. I., Della Pietra A. C., III, George D. L., Murphy M. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohrum M. A., Woods D. B., Ludwig R. L., Balint E., Vousden K. H. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:8521–8532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8521-8532.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stommel J. M., Marchenko N. D., Jimenez G. S., Moll U. M., Hope T. J., Wahl G. M. EMBO J. 1999;18:1660–1672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A. J. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine A. J. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihara M., Erster S., Zaika A., Petrenko O., Chittenden T., Pancoska P., Moll U. M. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leu J. I., Dumont P., Hafey M., Murphy M. E., George D. L. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haupt Y., Rowan S., Shaulian E., Vousden K. H., Oren M. Genes. Dev. 1995;9:2170–2183. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee W., Harvey T. S., Yin Y., Yau P., Litchfield D., Arrowsmith C. H. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1994;1:877–890. doi: 10.1038/nsb1294-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clore G. M., Ernst J., Clubb R., Omichinski J. G., Kennedy W. M., Sakaguchi K., Appella E., Gronenborn A. M. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:321–333. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeffrey P. D., Gorina S., Pavletich N. P. Science. 1995;267:1498–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.7878469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLure K. G., Lee P. W. EMBO J. 1998;17:3342–3350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hupp T. R., Lane D. P. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman P. N., Chen X., Bargonetti J., Prives C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:3319–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hainaut P., Hall A., Milner J. Oncogene. 1994;9:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halazonetis T. D., Kandil A. N. EMBO J. 1993;12:5057–5064. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zong W. X., Li C., Hatzivassiliou G., Lindsten T., Yu Q. C., Yuan J., Thompson C. B. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:59–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.