Abstract

Yeast tRNAHis guanylyltransferase, Thg1, is an essential protein that adds a single guanine to the 5′ end (G−1) of tRNAHis. This G−1 residue is required for aminoacylation of tRNAHis by histidyl-tRNA synthetase, both in vitro and in vivo. The guanine nucleotide addition reaction catalyzed by Thg1 extends the polynucleotide chain in the reverse (3′-5′) direction of other known polymerases, albeit by one nucleotide. Here, we show that alteration of the 3′ end of the Thg1 substrate tRNAHis unleashes an unexpected reverse polymerase activity of wild-type Thg1, resulting in the 3′-5′ addition of multiple nucleotides to the tRNA, with efficiency comparable to the G−1 addition reaction. The addition of G−1 forms a mismatched G·A base pair at the 5′ end of tRNAHis, and, with monophosphorylated tRNA substrates, it is absolutely specific for tRNAHis. By contrast, reverse polymerization forms multiple G·C or C·G base pairs, and, with preactivated tRNA species, it can initiate at positions other than −1 and is not specific for tRNAHis. Thus, wild-type Thg1 catalyzes a templated polymerization reaction acting in the reverse direction of that of canonical DNA and RNA polymerases. Surprisingly, Thg1 can also readily use dNTPs for nucleotide addition. These results suggest that 3′-5′ polymerization represents either an uncharacterized role for Thg1 in RNA or DNA repair or metabolism, or it may be a remnant of an earlier catalytic strategy used in nature.

Keywords: polymerase, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, THG1, tRNA modification

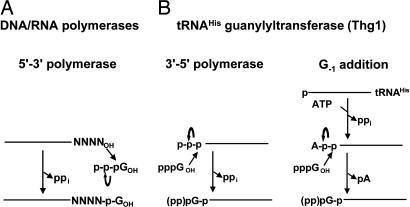

All known polymerases catalyze the addition of nucleotides in the 5′-3′ direction, including classical DNA and RNA polymerases, as well as telomerase, reverse transcriptase, and a number of template-independent RNA polymerases (1–3). These polymerases universally catalyze the same reaction, involving attack by the polynucleotide 3′-OH on the 5′-triphosphate of an incoming NTP, to yield an extended polynucleotide and a pyrophosphate side product from the NTP (Fig. 1A). However, polymerization could just as easily occur chemically in the reverse (3′-5′) direction with the same functional groups, by attack of the 3′-OH of the incoming nucleotide on a 5′-triphosphorylated polynucleotide (Fig. 1B). We show here that tRNAHis guanylyltransferase can act in this capacity as a reverse polymerase, catalyzing the 3′-5′ addition of multiple nucleotides to the polynucleotide chain in a reaction that is distinct from its known physiological role.

Fig. 1.

Nucleotide addition reactions catalyzed by 5′-3′ polymerases and tRNAHis guanylyltransferase (Thg1).

tRNAHis species are unique among tRNAs because they contain an additional universally conserved G residue at the −1 position (G−1), whereas only one other characterized tRNA has any nucleotide at that position (4, 5). In prokaryotes, G−1 is genome-encoded, forms a standard base pair with C73, and is retained during tRNAHis maturation because RNase P cleaves pre-tRNA at the −1 position (6). By contrast, in eukaryotes, G−1 is added posttranscriptionally by tRNAHis guanylyltransferase, which is encoded in yeast by the essential THG1 gene (7), and it catalyzes the addition of a guanine nucleotide to the 5′ end of tRNAHis across from residue A73 of the tRNA, the nucleotide immediately preceding the CCA 3′ end (7–9). G−1 addition activity is crucial for aminoacylation of tRNAHis in vivo (10), consistent with the demonstration that G−1 is necessary and sufficient for histidyl-tRNA synthetase activity in vitro (11–13).

Because G−1 modification is a strong determinant of histidyl-tRNA synthetase activity, Thg1 must be extraordinarily specific for tRNAHis to prevent misacylation of other tRNAs. Indeed, Thg1 prefers its physiological substrate, monophosphorylated tRNAHis (p-tRNAHis), which arises after cleavage by RNase P, by >10,000-fold over other p-tRNA species (14). As for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, where the anticodon is often a major determinant of tRNA specificity, the tRNAHis GUG anticodon is the source of Thg1 specificity because it is both necessary and sufficient for Thg1 activity in vitro (14). The three-step enzymatic reaction catalyzed by Thg1 involves the activation of the 5′ end of the tRNA by adenylylation, attack of the 3′-OH of GTP on the activated intermediate, and removal of the 5′-pyrophosphate, yielding mature G−1-containing tRNAHis and AMP (Fig. 1B) (7, 8). These chemical steps are also strikingly similar to those catalyzed by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (14). However, despite these similarities between Thg1 and synthetases, as well as the proximity of their sites of action at the top of the tRNA aminoacyl-acceptor stem, there is no identifiable homology between Thg1 and the synthetases or even between Thg1 and any other enzyme family.

Formally, the Thg1 G−1 addition reaction is the 3′-5′ extension of a polynucleotide chain, albeit by one nucleotide. Moreover, there is an alternative mode of Thg1 activity that more closely resembles a polymerase, in which triphosphorylated tRNAHis (ppp-tRNAHis) is used directly for the addition of G−1 (Fig. 1B), bypassing the ATP requirement for activation (7).

We report here that wild-type Thg1 can catalyze multiple rounds of reverse polymerization with certain substrates. While investigating the tRNAHis determinants for Thg1 activity, we found that alteration of the conserved nucleotide A73 of tRNAHis unleashes a previously unexpected reverse polymerase function of wild-type Thg1, resulting in the 3′-5′ extension of the polynucleotide chain by multiple nucleotides. Characterization of Thg1 reverse polymerization shows that this activity, unlike the addition of G−1, is template-dependent, recognizing G·C Watson–Crick base pairs. Moreover, reverse polymerization is not specific for tRNAHis or for starting at the −1 position of tRNA, provided that the activated (triphosphorylated) form of the tRNA substrate is used in the assays.

Results

Thg1 Adds Multiple Guanine Residues to the 5′ End of A73C Variant tRNAHis Species.

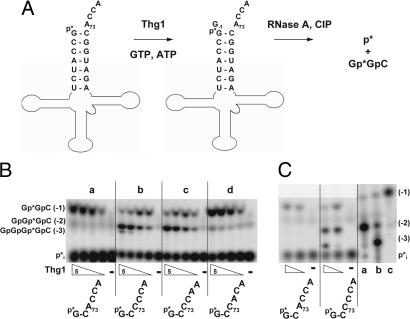

Although Thg1 normally adds a single guanine nucleotide to the 5′ end of tRNAHis, Thg1 can add multiple guanine nucleotides to a variant tRNAHis that bears C73 instead of the A73 that is universally conserved in eukaryotic tRNAHis species (4, 15). We demonstrated this phenomenon with a sensitive assay that exploits the phosphatase resistance that occurs when G−1 is added to 5′ end-labeled tRNAHis (14). After incubation of tRNAHis with Thg1, treatment with RNase A and phosphatase yields the internally labeled trimer G[32P]pGpC if G−1 has been added, or 32Pi from unreacted substrate (Fig. 2A), which are well separated by TLC (Fig. 2Ba). However, reaction of Thg1 with a tRNAHis variant bearing A73C (tRNAHis C73CCA) also yields a prominent second product and a small amount of a third product at higher concentrations of Thg1 (Fig. 2Bb). These additional products comigrate on TLC with chemically synthesized oligonucleotide standards corresponding to G−2 and G−3 reaction products (Fig. 2C), and they are presumed to be these species because only GTP and ATP are present in the reactions, and all reaction products are sensitive to RNase T1, producing Gp (data not shown). Similarly, reaction of Thg1 with a tRNAHis C73CAA variant results in a G−2 product at higher concentrations of Thg1 but no G−3 product (Fig. 2Bc), whereas reaction with a tRNAHis C73ACA variant yields only a G−1 product (Fig. 2Bd). Thus, it appears that formation of additional products depends on the identity of the A73CCA 3′ end of tRNA.

Fig. 2.

Thg1 exhibits 3′-5′ reverse polymerase activity with tRNAHis variants containing altered 3′ ends. (A) Schematic of Thg1 assay with 5′-32P-labeled tRNAHis. After RNase A and phosphatase treatment, the Thg1 reaction products [G[32P]pGpC (Gp*GpC) and longer species] are resolved from 32Pi derived from substrate by TLC. (B) Thg1 adds guanine nucleotides to A73C tRNAHis variants. Activity with 5′-32P-labeled wild-type tRNAHis (a), tRNAHis C73CCA (b), tRNAHis C73CAA (c), or tRNAHis C73ACA (d) variants is shown using 5-fold serial dilutions of purified Thg1 (50 μg/ml to 0.4 μg/ml); −, no Thg1 added. (C) Confirmation of identity of additional 5′ reaction products formed by Thg1. Comigration of tRNAHis C73CCA G−1, G−2, and G−3 nucleotide addition products with [3′-32P]Cp-labeled, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP)-treated oligonucleotide standards (GpGp*C, GpGpGp*C, and GpGpGpGp*C; lanes c, a, and b, respectively) is shown after resolution by silica TLC.

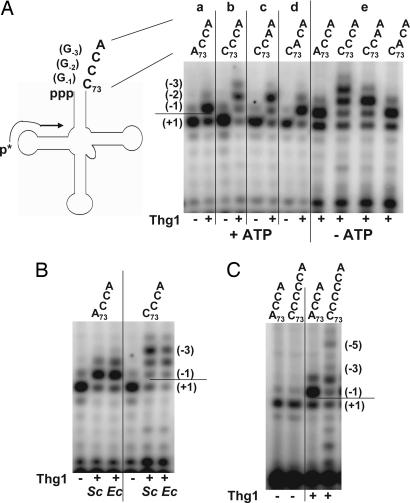

Examination of Thg1 activity with the corresponding ppp-tRNA substrates shows that Thg1 has the same spectrum of products with this alternatively activated tRNAHis substrate as with the p-tRNAHis species, which require activation by ATP (Fig. 3A). As measured by primer extension product length and intensity, Thg1 efficiently adds a single guanine nucleotide residue to ppp-tRNAHis (Fig. 3Aa), whereas up to three nucleotides are added to a ppp-tRNAHis C73CCA variant (Fig. 3Ab), two nucleotides are added to a ppp-tRNAHis C73CAA variant (Fig. 3Ac), and a single nucleotide is added to a ppp-tRNAHis C73ACA variant (Fig. 3Ad). We conclude that Thg1 catalyzes authentic 3′-5′ reverse polymerization, defined as extension of the 5′ end of a polynucleotide chain by more than a single nucleotide. Because addition of multiple guanine nucleotides to the ppp-tRNAHis variants is at least as efficient in the absence of ATP (Fig. 3Ae), we conclude that Thg1 does not require ATP to activate the 5′ end of the RNA for multiple-nucleotide additions; rather, we infer that the second and third guanine nucleotide additions, like the first guanine nucleotide addition, are powered by hydrolysis of pyrophosphate from the growing polynucleotide chain. Moreover, the slightly enhanced addition activity observed with the ppp-tRNAHis C73CCA variant in the absence of ATP suggests that ATP in fact inhibits the multiple-addition reaction. Because yeast Thg1 purified from E. coli exhibits the same multiple-nucleotide addition activity, we conclude that this activity is intrinsic to Thg1 protein (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Thg1 adds guanine nucleotides to the 5′ end of tRNAHis variants in a template-dependent reaction. (A) Thg1 reverse polymerization does not require ATP with ppp-tRNA. Primer extension analysis of Thg1 reaction products is shown with wild-type (a), C73CCA (b), C73CAA (c), or C73ACA (d) ppp-tRNAHis species in the presence of ATP (a–d) or in the absence of ATP (e). The horizontal line denotes the expected primer extension stop with unreacted transcript (position +1), and additional nucleotide incorporations are indicated by (−1), (−2), and (−3). The primer position is indicated by an arrow on the tRNA diagram; G−1, G−2, and G−3 nucleotides incorporated by Thg1 with the tRNAHis C73CCA variant are indicated in parentheses. (B) Thg1 reverse polymerization does not depend on the source of purified Thg1 protein. Shown is the primer extension of reaction products from the addition of G−1 (with wild-type tRNAHis) and reverse polymerization (with tRNAHis C73CCA) using yeast Thg1 purified from either Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) or Escherichia coli (Ec). (C) Thg1 adds guanosine residues according to the number of C residues at the 3′ end of the tRNA species. Thg1 reaction products with tRNAHis C73CCCCA were analyzed by primer extension, demonstrating the addition of up to five nucleotides to the 5′ end of the tRNA.

The addition of multiple guanine nucleotides by Thg1 is an efficient RNA reverse polymerization activity. Thg1 reverse polymerization with tRNAHis C73CCA and other variants occurs with similar efficiency (Figs. 2B and 3A) and on the same time scale (data not shown) as for the addition of G−1 to wild-type tRNAHis, whether the compared substrates are ppp-tRNAHis species or p-tRNAHis species. Furthermore, there is an element of template dependence in the reverse polymerization because the number of guanine nucleotides added to the 5′ end of both p-tRNAHis and ppp-tRNAHis variants appears to be directed by the number of consecutive cytidine residues at the 3′ end, starting at nucleotide 73 (Figs. 2B and 3). Indeed, up to five guanine residues are added across from the 3′ end of tRNAHis C73CCCCA (Fig. 3C).

Thg1 Reverse Polymerase Activity Is Template-Dependent Beyond Position −1.

Closer examination of the nucleotide dependence of the reverse polymerase activity of Thg1 demonstrates that it is strictly template-dependent and recognizes G·C and C·G base pairs. Consistent with a templated nucleotide addition reaction, Thg1 can catalyze multiple rounds of reverse polymerization at the 5′ end of tRNAHis C73CCA only in the presence of GTP (Fig. 4Ab), whereas with each of the other NTPs, Thg1 can catalyze only a single addition reaction. Furthermore, reverse polymerization is not restricted to the addition of guanine nucleotide because up to three cytidine nucleotides are added to the 5′ end of tRNAHis G73GGA with CTP (Fig. 4Ac), but only one nucleotide is added with each of the other NTPs. However, Thg1 does not appear to recognize U·A base pairs under these conditions because tRNAHis U73UUA or A73AAA species are not substrates for reverse polymerization in the presence of ATP or UTP, respectively (Fig. 4 Ad and Ae). Thus, polymerization beyond the −1 position appears to require formation of a canonical G−1·C73 or C−1·G73 base pair and appears to extend further only if the next templated nucleotides at position 74 and beyond are G or C residues. Moreover, Thg1 is not restricted to multiple-nucleotide additions of a single NTP because addition to a tRNAHis G73CCA variant is somewhat more extensive in the presence of both GTP and CTP than it is with GTP alone (Fig. 4Af). The relatively weaker extension observed with this substrate suggests that some nontemplated G−1 addition occurs opposite G73, which would create a nonpaired and therefore nonextendable substrate. Indeed, as shown below, the addition of G is preferred at the −1 position.

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide dependence of Thg1 reverse polymerization compared with the addition of G−1. (A) Nucleotide dependence of Thg1 activity with ppp-tRNAHis species. Thg1 reaction products formed in the presence of individual NTPs and ppp-tRNAHis substrates (with 3′ end sequence indicated below each panel) were analyzed by primer extension. Lanes G, A, U, and C show each NTP added as indicated; −, no nucleotide; NP, no Thg1. (B) Thg1 is specific for the addition of G at position −1 in the presence of all four NTPs. Thg1 reaction products with 5′-32P-labeled wild-type tRNAHis are shown in the presence of GTP and ATP (a) or a mixture of all four NTPs (GTP, ATP, UTP, and CTP) (b–d), each at a final concentration of 1 mM (b), 0.4 mM (c), or 0.1 mM (d); −, no added nucleotide; NP, no Thg1. (Left) RNase A and CIP treatment of reaction products, resolved by standard silica TLC. (Right) RNase T2 digestion of reaction products, to release 3′-labeled Np resulting from the addition of nucleotide at position −1, resolved by polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose TLC in 0.5 M sodium formate (pH 3.5). Gp, Ap, Up, and Cp, migration of 3′-phosphorylated standards as visualized by fluorescence quenching.

Templated reverse polymerization by Thg1 beyond position −1 is in sharp contrast to the addition reaction that occurs at the −1 position because Thg1 can add any nucleotide at the −1 position with each of the ppp-tRNA species examined for reverse polymerization (Fig. 4 Ab–Af), as well as with wild-type tRNAHis (Fig. 4Aa). However, consistent with the known role of Thg1, when all four NTPs are present, Thg1 adds exclusively G at position −1 of wild-type p-tRNAHis opposite A73, as indicated by RNase T2 analysis of reaction products, which yields only Gp (Fig. 4B).

3′-5′ Reverse Polymerization of ppp-tRNA Substrates by Thg1 Is Not Specific for tRNAHis.

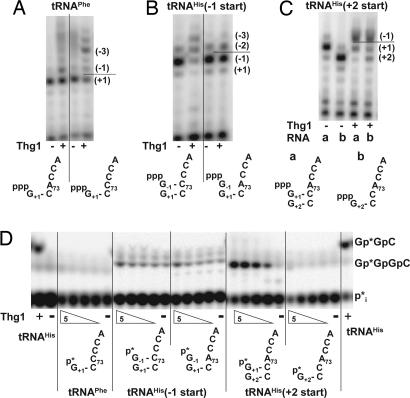

Although our previous results demonstrate that the addition of Thg1 G−1 activity is at least 10,000-fold more specific for tRNAHis than for other tRNAs when assayed in vitro with the physiological p-tRNAHis substrate (14), Thg1 is not nearly as specific when assayed with ppp-tRNA substrates for either G−1 addition activity (14) or reverse polymerization activity. Thus, Thg1 adds a single G residue to wild-type ppp-tRNAPhe, which normally contains an A73CCA 3′ end (Fig. 5A), and Thg1 efficiently adds up to three guanine residues to a ppp-tRNAPhe C73CCA variant (Fig. 5A). These results demonstrate that reverse polymerase activity does not inherently depend on recognition of tRNAHis and therefore could potentially occur with other substrates in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Thg1 reverse polymerase activity is not specific for tRNAHis and does not need to begin at the −1 position. (A) tRNAPhe C73CCA is a substrate for Thg1 reverse polymerization. Thg1 catalyzes the addition of G−1 to wild-type ppp-tRNAPhe and addition of multiple G residues to ppp-tRNAPhe C73CCA, as analyzed by primer extension. (B) Reverse polymerization can initiate at position −1. Thg1 catalyzes addition of G−2 and G−3 to a tRNAHis 76-mer transcript that already contains G−1 when this G−1 residue is base-paired with C73, but not when it is opposite A73, as analyzed by primer extension. (C) Reverse polymerization can initiate at position +2. Thg1 catalyzes the addition of G+1 and G−1 to a tRNAHis variant that begins at the +2 position, yielding the same G−1-containing reaction product as a control RNA species that begins with G+1, as analyzed by primer extension. (D) Thg1 does not add additional residues to p-tRNAHis species that do not begin with G+1. 5′-32P-labeled wild-type or variant tRNAHis and tRNAPhe species, as indicated below each panel, were assayed in the presence of GTP and ATP. GpGpC is the reaction product observed with wild-type tRNAHis; GpGpGpC is the tetramer RNase A reaction product expected for G+2 control RNA, which has an altered G2·C71 base pair.

Reverse polymerization by Thg1 also does not need to initiate at the −1 position. Indeed, a G−1-containing tRNAHis C73CCA transcript, which is the same molecule as the G−1 addition product that results from Thg1 activity on tRNAHis C73CCA, is a substrate for continued addition of up to two additional nucleotides as demonstrated by primer extension (Fig. 5B). However, the corresponding G−1-containing wild-type tRNAHis A73CCA 76-mer transcript cannot be extended further, presumably because it is the same molecule as mature tRNAHis, with an unpaired G−1 opposite A73 (Fig. 5B). Likewise, Thg1 adds two nucleotides to a tRNAHis transcript that initiates at residue +2; the first nucleotide addition restores the G+1 5′ end, and the second adds G−1 opposite A73, yielding the same G−1-containing product as is observed with a control tRNAHis transcript that starts at G+1 (Fig. 5C). However, the addition of a nucleotide initiating at either G−1 or at G+2 or to the tRNAPhe C73CCA variant was not detected when the corresponding p-tRNA species were assayed for activity with 5′-end-labeled p-tRNA; in this assay, the only p-tRNA species that was a substrate for Thg1 was the wild-type control p-tRNAHis bearing the altered 2·71 base pair (Fig. 5D). The lack of reaction with all other p-tRNA variants is consistent with the high selectivity of Thg1 for mature p-tRNAHis.

Thg1 Efficiently Incorporates dGTP in both the G−1 Addition and Reverse Polymerization Reactions.

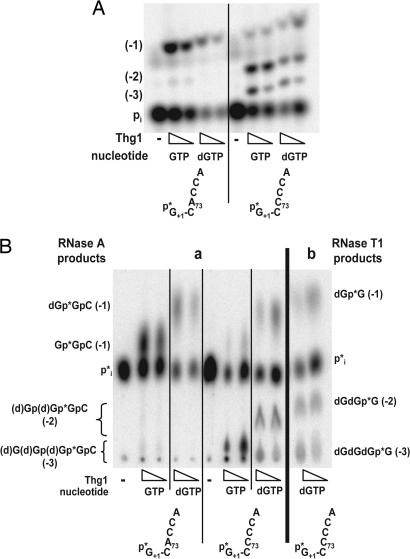

To explore further the generality of the Thg1 reaction, we investigated Thg1 activity with deoxynucleotides. Surprisingly, Thg1 appears to incorporate dGTP with efficiency comparable with that of GTP, as indicated by the similar amounts of addition products observed with both nucleotides, using 5′-end-labeled wild-type p-tRNAHis and p-tRNAHis C73CCA substrates (Fig. 6A). Although the deoxy- and ribonucleotide reaction products are not resolved from one another in this TLC system (Fig. 6A), they are easily resolved with another TLC assay system to analyze the same reaction products (Fig. 6Ba), and as expected, the products of dGTP incorporation are resistant to RNase T1 treatment (Fig. 6Bb). Thus, dGTP is incorporated and not contaminating GTP.

Fig. 6.

Thg1 adds deoxynucleotides and ribonucleotides to the 5′ end of tRNAHis. (A) Comparison of Thg1 activity in the presence of GTP or dGTP. Thg1 was assayed with 5′-32P-labeled wild-type or C73CCA tRNAHis and the standard RNase A/CIP assay in the presence of either GTP or dGTP as indicated. (B) Verification of deoxyguanosine nucleotide incorporation into tRNA. (a) Samples from A were resolved by TLC on PEI-cellulose in 0.5 M sodium formate (pH 3.5), where dG-containing reaction products migrate differently from the corresponding ribonucleotide-containing products. (b) Samples from A were treated with RNase T1 and CIP and resolved in the same system.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that wild-type Thg1 has an unexpected second catalytic activity in addition to its known role of adding G−1 to the 5′ end of tRNAHis (7, 10): Thg1 can catalyze a reverse (3′-5′) polymerase activity, adding multiple nucleotides to the 5′ end of variant tRNA species in a template-dependent reaction.

Like the normal G−1 addition reaction, reverse polymerization requires ATP with p-tRNAHis variants that begin at +1. Reverse polymerization with all other substrate tRNAs requires ppp-tRNA and can occur in the absence of ATP. Presumably, as with the normal G−1 addition, these triphosphorylated substrates bypass the ATP requirement because they are already activated for the first nucleotide addition, and this and subsequent nucleotide addition steps are powered by pyrophosphate release of the β- and γ-phosphates from the triphosphorylated nucleotide at the 5′ end of the growing polynucleotide chain (Fig. 1B). In support of this mechanism for reverse polymerization, a substrate tRNA that begins at −1 and therefore emulates the product of the first addition reaction is active only if it is triphosphorylated (Fig. 5B). This mechanism of reverse polymerization is very similar to the pyrophosphate release that powers conventional 5′-3′ polymerization, although in 5′-3′ polymerization the pyrophosphate originates from the incoming NTP instead of the polynucleotide (Fig. 1B).

Under normal circumstances in the cell, tRNAs other than tRNAHis are presumably not substrates for reverse polymerization or G−1 addition by Thg1 because there is no ready source of activated 5′ ends of the tRNAs. There is no naturally occurring mature ppp-tRNA that would be a substrate for Thg1, and activation by adenylylation occurs only with 75-mer p-tRNAHis through Thg1 recognition of the anticodon (14), consistent with the crucial role of G−1-containing tRNAHis in charging tRNAHis in vitro (11–13) and in vivo (10). Furthermore, tRNAHis nucleotide addition is restricted to a single guanosine residue because Thg1 adds only the single required G−1 opposite the discriminator A73 (Figs. 2B and 3A). This feature emphasizes the importance of the conserved A73 in eukaryotic tRNAHis because Thg1 could add additional residues opposite the conserved prokaryotic discriminator, C73.

The incorporation of G−1 into tRNAHis in archaeal species is more complicated. Despite the nearly universal conservation of C73 in Archaea, there are at least some species that appear to require posttranscriptional G−1 addition opposite C73 because their tRNAHis genes lack a genomically encoded G−1, and the corresponding organisms have a predicted Thg1 ortholog. Thus, archaebacterial Thg1 homologs may possess additional mechanisms to ensure addition of only a single guanine residue across from C73. Consistent with this possibility, the archaeal THG1 orthologs are much less conserved than eukaryotic orthologs, and, although both human and Candida albicans THG1 orthologs can complement a thg1 conditional yeast strain, the archaeal ortholog from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum does not complement a thg1 mutant under the same expression conditions (data not shown).

The results presented here, coupled with previous results, illustrate a bewildering array of nucleotide recognition and use by Thg1 protein. During the addition of G−1, Thg1 recognizes the 5′ end of ATP for adenylylation, the 3′ end of incoming NTPs for nucleotidyl transfer, and the 5′-pyrophosphate of the product tRNA for pyrophosphatase activity (Fig. 1). In addition, reverse polymerization of ppp-tRNAHis substrates by Thg1 at positions other than −1 requires formation of a G·C or C·G base pair and the potential to form similar base pairs at subsequent addition sites, whereas any nucleotide can be added at position −1 whether or not a base pair can be formed (Fig. 4). Thus, Thg1 has the potential both to recognize and select for nucleotides that participate in Watson–Crick base pairing for polymerization and to recognize and select guanosine in a non-Watson–Crick interaction opposite A73. Although Thg1 base pair recognition is limited to G·C but apparently not U·A base pairs (Fig. 4), it is not limited by the normal tRNA 3′ end in the number of nucleotides that can be added because a tRNA with five C residues at the 3′ end (tRNAHis C73CCCCA) can be extended by up to five nucleotides (Fig. 3C). The multiple modes of nucleotide selection by the relatively small (28 kDa) Thg1 suggest conformational changes during the course of the reaction, and they are reminiscent of the multiple use of different nucleotides by the CCA-adding enzyme, which restructures its single active site for accommodation of each new nucleotide substrate during nontemplated addition to the 3′ end of the tRNA (16–18).

We emphasize that the reverse polymerase activity described here is distinct from the addition of G−1 to tRNAHis that occurs in vivo during tRNAHis maturation because the addition of G−1 is not dependent on base pair formation, does not require prior activation of the tRNAHis 5′ end, and is absolutely specific for p-tRNAHis that arises after cleavage of pre-tRNA by RNase P. By contrast, reverse polymerization depends on base pair formation and is not specific for the correct 5′ end of tRNAHis. We also emphasize that Thg1 catalyzes reverse polymerization on tRNAHis and tRNAPhe C73CCA substrates at least as efficiently as it catalyzes its known physiological G−1 addition reaction on wild-type tRNAHis (Figs. 2B, 3A, and 5A) and that both of these reactions occur on the same time scale (data not shown). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the reverse polymerase activity has a function. It is possible that the reverse polymerization activity of Thg1 might simply be a remnant of an earlier 3′-5′ polymerase activity of this family of proteins, which could have competed with or acted together with the activities of conventional 5′-3′ polymerases for replication or repair functions. However, it is particularly difficult to reconcile the evolutionary retention of a distinct Thg1 reverse polymerization activity that forms G·C and C·G base pairs because such Watson–Crick base pair recognition and use would not be expected of an enzyme whose only role is to add G−1 opposite A73 of tRNAHis in vivo. Rather, the reverse polymerization described here may reflect an additional Thg1 activity that is used in the cell. Indeed, there is an apparent 3′-5′ polymerization activity that functions to edit the 5′ end of mitochondrial tRNA in Acanthamoeba castellanii and Spizellomyces punctatus although, unlike Thg1, this activity does not proceed beyond the normal 5′ end of the tRNA (19–21). Because the gene product(s) that catalyze this reaction are unknown, the relationship between these activities is unclear. Thg1 might act in a similar or related capacity in 3′-5′ polymerization of tRNA substrates, although this role would depend on some additional mechanism to activate the 5′ ends of the tRNA species.

The ability of Thg1 to use deoxynucleotides may also have implications for Thg1 function. Thg1 incorporates deoxyguanosine with an efficiency similar to its ribonucleotide counterpart for both reverse polymerization with tRNAHis C73CCA and the addition of G−1 with wild-type tRNAHis (Fig. 6). This property of Thg1 is in contrast to the highly selective preferences exhibited by most 5′-3′ RNA and DNA polymerases for their nucleotide substrates (22). However, several members of the polymerase X family of DNA damage repair polymerases also exhibit a lack of discrimination toward nucleotide sugar species in vitro, which may be important for their proposed functions in vivo, including polymerization at points in the cell cycle when cellular dNTP levels are low and signaling the site of repair by marking the chromosome with incorporated ribonucleotides (23, 24). Thus, the ability of Thg1 to use deoxynucleotides suggests that any additional functions of Thg1 might employ either dNTPs or rNTPs. In this regard, Thg1 has recently been shown to associate with the origin recognition complex and to be implicated in the G2/M transition in yeast (25), suggesting a potential role at this site.

Materials and Methods

Sources of Thg1.

Thg1 protein was purified from both S. cerevisiae and E. coli as described in ref. 14. Unless otherwise indicated, the Thg1 protein used for all assays was the yeast purified protein.

Variant tRNA Species.

All tRNA variants with the exception of C73CCCCA tRNAHis were cloned into a previously described pUC13-based plasmid under control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter for purposes of in vitro transcription (7). tRNAHis and tRNAPhe variants were all created by mutagenic PCR, with the T7 RNA polymerase promoter encoded by the 5′ PCR primer and subsequent ligation of the amplified PCR product into the PstI/BamHI sites of the previously described EMP835 (7). All tRNA-containing plasmids were verified by sequencing. The tRNAHis C73CCCCA RNA substrate was made by ligation of a phosphorylated synthetic RNA oligonucleotide (5′-ggagauggcCCCCCA) to the 3′ end of a truncated tRNAHis transcript, ending at A63, using 10 units/μl T4 DNA ligase (USB Corp.) in the presence of a complementary DNA oligonucleotide spanning the ligation site.

Thg1 Activity Assay with [5′-32P]tRNA.

[5′-32P]tRNA species were prepared by phosphatase treatment of in vitro transcripts followed by labeling with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche Applied Biosciences) to a final specific activity of ≈7,000 Ci/mmol (1 Ci = 37 GBq). The [5′-32P]tRNA was used as the substrate in a Thg1 assay containing 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, 125 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, and, unless otherwise indicated, 1 mM each GTP and ATP. Enzyme titration assays consisted of 5-fold serial dilutions (≈50 μg/ml to 0.4 μg/ml) of purified Thg1. Reactions were started by the addition of enzyme and carried out at room temperature. After 5–6 h, the reaction was stopped by removal of an aliquot (4 μl) to a new tube containing 0.5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA and 0.5 μl of 10 mg/ml RNase A followed by digestion for 10–30 min at 50°C and treatment with 0.5 unit of CIP in 1× phosphatase reaction buffer in a final volume of 6 μl at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions were spotted to silica TLC plates (EM Science) and resolved in an n-propyl alcohol/NH4OH/H2O (55:35:10) solvent system. The plates were visualized and quantified with a PhosphorImager and imagequant software.

5′ End Analysis by Primer Extension.

Thg1 reactions were carried out for 6 h at room temperature in the same buffer described above with 1 μM unlabeled triphosphorylated tRNA in a 10-μl reaction volume containing 1 μM purified Thg1. Unless otherwise noted, each reaction contained a 1 mM concentration of the indicated NTP. Thg1-treated tRNAs were purified by extraction with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol, concentrated by precipitation with ethanol, and resuspended in 10 μl of buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM EDTA. Two microliters of each purified tRNA was used as the template in primer extension reactions employing a 5′-end-labeled primer specific for tRNAHis (5′-ACTAACCACTATACTAAGA-3′) as shown in Fig. 2A or a similar tRNAPhe-specific primer (5′-TGGCGCTCTCCCAACTG-3′). After the Thg1-treated tRNA template was annealed to 1 pmol of primer in a final volume of 5 μl, extension reactions were carried out with 8 units of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (AMV-RT) (20 units/μl; Promega) in the presence of a 0.4 mM concentration of each dNTP in 1× AMV-RT reaction buffer (Promega) in a final volume of 10 μl at 37°C for 1–2 h. The resulting products were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide/4 M urea gels, which were dried and visualized with the PhosphorImager.

Determination of 5′ Nucleotide Identity by RNase T2 Digestion.

5′ 32P-labeled wild-type tRNAHis was used in Thg1 reactions in the buffer described above with varied concentrations of all four NTPs (1 mM, 0.4 mM, or 0.1 mM each) and 1 μM purified Thg1 in a 10-μl reaction mixture for 6 h at room temperature. After 6 h, a portion (4 μl) of the reaction was stopped, digested, and analyzed as described above with EDTA and RNase A. Another 4-μl aliquot was removed to a new tube containing 0.5 unit of CIP in 1× alkaline phosphatase buffer in a final volume of 10 μl to remove the background from the remaining unreacted substrate tRNA. After 30 min at 37°C, the reaction products were purified by extraction with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and precipitation with ethanol. The resulting tRNA was resuspended in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 1 unit of RNase T2 and 0.5 μg of RNase A in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2)/1 mM EDTA and digested for 30 min at 50°C. Two microliters of each digestion reaction mixture was spotted to PEI-cellulose plates and developed in a 0.5 M sodium formate (pH 3.5) solvent system. The positions of unlabeled nucleotide standards were determined by spotting 2 μl of 10 mM solutions of GMP, UMP, AMP, or CMP and visualizing the resultant spots by fluorescence quenching.

Determination of Deoxyguanosine Incorporation by Resistance to RNase T1 Digestion.

Thg1 reactions were carried out as described above with 5′-32P-labeled tRNAHis (wild-type and C73CCA species) in the presence of 0.1 mM ATP and either 1 mM GTP or 1 mM dGTP for 5 h at room temperature. After digestion with RNase A and CIP, as described above, a 2-μl portion of the reaction mixture was removed to a new tube containing 2 μg of torula yeast tRNA and 0.5 unit of RNase T1 in 30 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) buffer in a final volume of 5 μl. The RNase T1 digestion was allowed to proceed for 30 min at 50°C, and then the reaction mixtures were treated with 0.5 unit of CIP in 1× alkaline phosphatase reaction buffer in a final volume of 6 μl. After 30 min at 37°C, 2 μl of each reaction mixture (both the original RNase A-treated and RNase A- + RNase T1-treated reactions) were spotted to PEI-cellulose TLC plates and resolved in the 0.5 M sodium formate (pH 3.5) solvent system.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Crary, S. Fields, M. Gorovsky, M. Gray, E. Grayhack, R. Green, and A. Hopper for advice and comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM52347.

Abbreviations

- CIP

calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- p-tRNA

monophosphorylated tRNA

- ppp-tRNA

triphosphorylated tRNA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Steitz T. A. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:17395–17398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aphasizhev R., Sbicego S., Peris M., Jang S. H., Aphasizheva I., Simpson A. M., Rivlin A., Simpson L. Cell. 2002;108:637–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schurer H., Schiffer S., Marchfelder A., Morl M. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:1147–1156. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprinzl M., Horn C., Brown M., Ioudovitch A., Steinberg S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:148–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnare M. N., Heinonen T. Y., Young P. G., Gray M. W. Curr. Genet. 1985;9:389–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00421610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orellana O., Cooley L., Soll D. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986;6:525–529. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu W., Jackman J. E., Lohan A. J., Gray M. W., Phizicky E. M. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2889–2901. doi: 10.1101/gad.1148603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahn D., Pande S. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22832–22836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooley L., Appel B., Söll D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:6475–6479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu W., Hurto R. L., Hopper A. K., Grayhack E. J., Phizicky E. M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8191–8201. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8191-8201.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nameki N., Asahara H., Shimizu M., Okada N., Himeno H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:389–394. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudinger J., Florentz C., Giege R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5031–5037. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.23.5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudinger J., Felden B., Florentz C., Giege R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1997;5:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackman J. E., Phizicky E. RNA. 2006 (April) doi: 10.1261/rna.54706. 10.1261/rna.54706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marck C., Grosjean H. RNA. 2002;8:1189–1232. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202022021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong Y., Li F., Wang J., Weiner A. M., Steitz T. A. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi P. Y., Maizels N., Weiner A. M. EMBO J. 1998;17:3197–3206. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yue D., Weiner A. M., Maizels N. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:29693–29700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonergan K. M., Gray M. W. Science. 1993;259:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.8430334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lonergan K. M., Gray M. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4402. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.18.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bullerwell C. E., Gray M. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2463–2470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose A. M., Joyce P. B., Hopper A. K., Martin N. C. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:5652–5658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nick McElhinny S. A., Ramsden D. A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2309-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bebenek K., Garcia-Diaz M., Patishall S. R., Kunkel T. A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20051–20058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice T. S., Ding M., Pederson D. S., Heintz N. H. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:832–835. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.4.832-835.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]