Abstract

We show that activation of the recombinant LHR in mouse Leydig tumor cells (MA-10 cells) leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc (Src homology and collagen homology) and the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos (Son of sevenless), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras. Since a dominant-negative mutant of Shc inhibits the LHR-mediated activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 we conclude that the LHR-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is mediated, at least partially, by the classical pathway utilized by growth factor receptors.

We also show that the endogenous epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) present in MA-10 cells is phosphorylated upon activation of the LHR. The LHR-mediated phosphorylation of the EGFR and Shc, the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 are inhibited by expression of a dominant-negative mutant of Fyn, a member of the Src family kinases (SFKs) expressed in MA-10 cells and by PP2, a pharmacological inhibitor of the SFKs. These are also inhibited, but to a lesser extent, by AG1478, an inhibitor of the EGFR kinase.

We conclude that the SFKs are responsible for the LHR-mediated phosphorylation of the EGFR and Shc, the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos, the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

Introduction

A number of studies ranging from the effects of hCG injections on rats (1), the phenotype of individuals harboring mutations of the LHR gene (2, 3), as well as the phenotype of the LHR knockout mice (4, 5) and the phenotypes of several transgenic mouse models that overexpress hCG or LH (6-8) clearly show that the LHR plays a role in the proliferation of Leydig cells. With this in mind we have begun a series of studies designed to identify LHR-dependent signaling pathways that could participate in the proliferation of Leydig cells (9, 10).

A ubiquitous pathway utilized by growth factors to activate the ERK1/2 cascade in many cell types begins with the trans-phosphorylation of their receptors in tyrosine residues. The phosphorylated tyrosines serve as docking sites for a number of adaptor molecules or enzymes. Shc is an adaptor that binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on growth factor receptors and itself undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by the activated receptors. The tyrosine phosphorylated Shc in turn becomes a docking site for another adaptor called Grb2 (growth factor receptor binding protein) that is usually bound to Sos, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras. Alternatively, other phosphotyrosine residues present in the activated growth factor receptors can serve as direct docking sites for the Grb2/Sos complex. Thus the tyrosine phosphorylation of a growth factor receptor results in the recruitment of a Shc/Grb2/Sos or a Grb2/Sos complex to the plasma membrane where Sos can activate Ras (11-16). The activated Ras in turn activates Raf, a protein kinase that phosphorylates and activates another protein kinase called MEK which in turn phosphorylates and activates ERK1/2 (reviewed in refs. 11-18).

Using MA-10 cells expressing either the endogenous mouse (m) LHR or the recombinant human (h) LHR we have previously shown that hCG activates the ERK1/2 cascade through a pathway that involves protein kinase A and Ras (9). Other studies suggest that a similar pathway is operative upon activation of the LHR in primary cultures of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells (9, 19), porcine granulosa cells (20),and immortalized rat granulosa cell lines (21). In more recent studies we have found that hCG activates Fyn and Yes, two members of the SFKs that are expressed in MA-10 cells and that the activation of these SFKs results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of other cellular proteins such as the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and paxillin (10).

Since SFKs can also activate some of the same pathways stimulated by growth factor receptors (22) we decided to test for the involvement of SFKs and classical tyrosine kinase cascades (see above) on the hCG-induced activation of the Ras-sERK1/2 pathway in MA-10 cells. The data presented here show that hCG enhances the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR and Shc, as well as the formation of protein complexes containing Shc and Sos. This tyrosine kinase cascade is stimulated by the SFKs and is involved in the hCG-induced activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and cells.

The expression vector coding for the hLHR-wt modified with the myc-epitope at the N-terminus has been described (23). The expression vectors for the wild-type and dominant-negative mutant (i.e., kinase-deficient mutant, K229M) of human Fyn were generously provided by Dr. Marylin Resh of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (24). The expression vector for the dominant-negative Shc is the human p52 Shc where tyrosine residues 239, 240 and 317 were mutated to phenylalanine. This mutant was fused to glutathione-S-transferase (GST) (25). The vector coding for this fusion protein was provided by Dr. Kodi Ravichandran of the University of Virginia (25).

The origin and handling of MA-10 cells were as described earlier (26) with recent modifications (10). Experiments were done using cells plated in 35 mm wells. Transfections were done in 1 ml of OPTIMEM supplemented with 700 μg/ml CaCl2.2H2O. Each well was transfected with a maximum of 2 μg of plasmid and Lipofectamine® at a ratio of 4-6 μl/μg of DNA (23). After a three-hour incubation each well received 150 μl of horse serum and the incubation was continued for another 16-24 hours. The medium was then replaced with assay medium (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 20 mM Hepes and 50 μg/ml gentamicin, pH 7.4) and the cells were incubated in this medium for another 16-18 hours. The transfection efficiency under these conditions is about 25% (23).

On the day of the assay the medium was replaced with 1 ml of fresh assay medium and hormones and other compounds were added as indicated in the figure legends. The concentrations of EGF and hCG used were empirically determined to be maximally effective (data not shown). Likewise, time course experiments (not shown) were done for all responses measured and the lengths of the incubations used here were chosen to coincide with the maximal responses obtained.

Western blots for ERK, EGFR and Shc phosphorylation

At the end of the stimulation period the medium was aspirated and the contents of 1 well were lysed with 100 μl of RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4) supplemented with an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche Applied Science (http://www.roche-appliedscience.com), 1 mM NaF and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The resulting lysates were clarified by centrifugation and assayed for protein content using the BCA protein assay kit from Bio-Rad Laboratories (http://www.bio-rad.com). Equal amounts of protein from each lysate (10-30 μg) were then resolved on 7.5% or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (23). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies using variable conditions as follows. Shc phosphorylated at tyrosine residues 239/240 and 317 was detected using phospho-specific antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (http://www.cellsignal.com). Total Shc was detected with an antibody from BD Transduction Laboratories (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/pharmingen/). EGFR phosphorylated at tyrosine residues 1068 or 1173 were detected using phospho-specific antibodies purchased-from Cell Signaling Technology (http://www.cellsignal.com) or Upstate Biotechnology (http://www.upstatebiotech.com). Total EGFR was detected using an antibody to the intracellular domain of the EGFR from Upstate Biotechnology (http://www.upstatebiotech.com). All of these blots were developed using a 1 hour incubation of the membranes with a 1:1,000 dilution of the appropriate antibodies. Phosphorylated ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 were detected during an overnight incubation with a phospho ERK1/2 antibody (used at a 1:500 dilution) or a total ERK1/2 antibody (used at a 1:1,000 dilution) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (http://www.scbt.com). All primary antibody incubations were followed by a second 1 h incubation with a 1:3,000 dilution of a secondary antibody covalently coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad Laboratories; http://www.bio-rad.com).

Shc immunoprecipitation

At the end of the desired incubation the medium was aspirated and the contents of 1 well were lysed in 100 μl of RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors as described above. The lysates from 6 wells were combined, clarified by centrifugation and assayed for protein content using the BCA protein assay kit from Bio-Rad Laboratories (http://www.bio-rad.com). Five hundred μl aliquots of the lysates containing identical amounts of protein (500-1000 μg) were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 3 μl of the Shc antibody (see above) that had been pre-bound to 30 μl of a 50% suspension of protein G Sepharose (obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; http://www.scbt.com). After extensive washing the immune complexes bound to the Sepharose beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer and subsequently resolved on SDS gels and transferred electrophoretically to membranes as described above. The immunoprecipitated Shc was detected with an antibody from BD Transduction Laboratories (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/pharmingen/) as described above and the co-immunoprecipitated Sos was detected using an overnight incubation of the membranes with a 1:250 dilution of an antibody to Sos from BD Transduction Laboratories (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/pharmingen/) followed by a 1 h incubation with a 1:3,000 dilution of a secondary antibody covalently coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad Laboratories; http://www.bio-rad.com). In order to detect tyrosine phosphorylated Shc blots of the immunoprecipitates were also incubated overnight with a 1:1,000 dilution of a phosphotyrosine antibody already coupled to horseradish peroxidase (from BD Transduction Laboratories; http://www.bdbiosciences.com/pharmingen/).

Ras activation assays

Ras activation was measured by using a GST fusion protein of the Ras binding domain of Raf-1 to “pulldown” the activated (i.e., GTP-bound) form of Ras as described previously (9, 27) with two exceptions. First, instead of purchasing the GST fusion protein we prepared our own by using a vector generously donated by Dr. J.L. Bos of the University Medical Center in Utrecht, (27). The GST fusion product was prepared as described elsewhere (27). Second, the bound (active) Ras was visualized in the blots using a 1 hour incubation with a 1:100 or 1:200 dilution of a K-Ras antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (http://www.scbt.com) rather than the antibody to all forms of Ras used previously (9). This change was introduced because probing Western blots of whole cell MA-10 lysates with antibodies to H-Ras, K-Ras and N-Ras revealed that K-Ras is the most abundant form.

Other methods

All immune complexes in the Western blots were visualized using the Super Signal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity detection system (Pierce Chemical Inc, Rockford, IL) and exposed to film or captured digitally with a Kodak Digital Imaging system (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY). Most of the images shown here are from film because the quality of the images is better. The quantitative analysis presented, however, was done with the Digital Imaging system. Quantitation of the digital images captured using this system is more accurate because of its wider dynamic range that makes signal saturation less likely. In addition, the software included with this imaging system can readily determine if an image is saturated thus preventing its quantitation. All phosphorylation data for Shc and the EGFR were corrected for the amount of Shc or EGFR present in the blots as determined with the appropriate antibodies (see above and Figs 1 and 3). ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays were not corrected because we have previously shown that the total levels of ERK1/2 do not change under these conditions and such corrections are unnecessary (9).

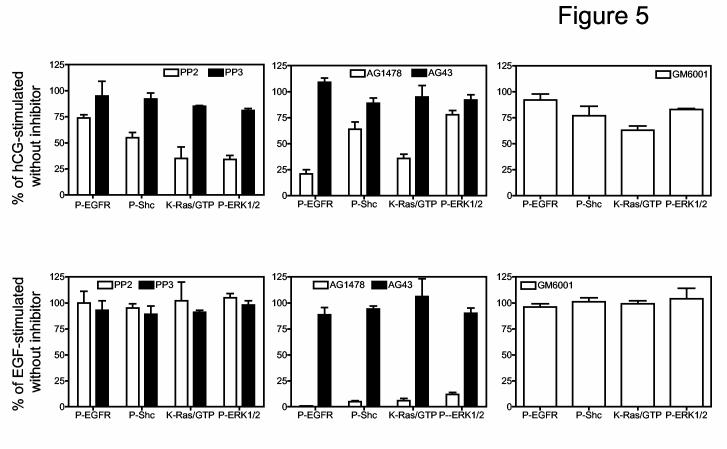

Figure 1.

. Human CG stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos. Panel A. MA-10 cells were transfected with the hLHR (1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) and incubated with buffer only (C), hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 15, 15 and 5 min, respectively. Western blots (WB) of whole cell lysates were developed using antibodies that recognize Shc, or Shc that is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues 239 and 240 (pY239, pY240) or tyrosine 317 (pY317) or as indicated. The signals of the phosphotyrosine antibodies obtained after EGF stimulation appear saturated because the Western blots were exposed for the same length of time to emphasize the difference in the magnitude of the signal detected in cells stimulated with EGF or hCG. Panel B. MA-10 cells were transfected with the hLHR (1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) and incubated with buffer only (C) or hCG (100 ng/ml) for 15 min or with buffer only (C) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 5 min as indicated. Shc was immunoprecipitated (IP) and Western blots of the immunoprecipitates were developed using phosphotyrosine (pY), Sos or Shc antibodies as indicated. The magnitude of the signals in the EGF and hCG stimulated cells should not be directly compared because the length of exposure of the films used for both sets of cells was different. The magnitude of the EGF-induced signals is in fact much higher than the magnitude of the hCG-induced signals (see text for details). Only the appropriate areas of the gel are shown.

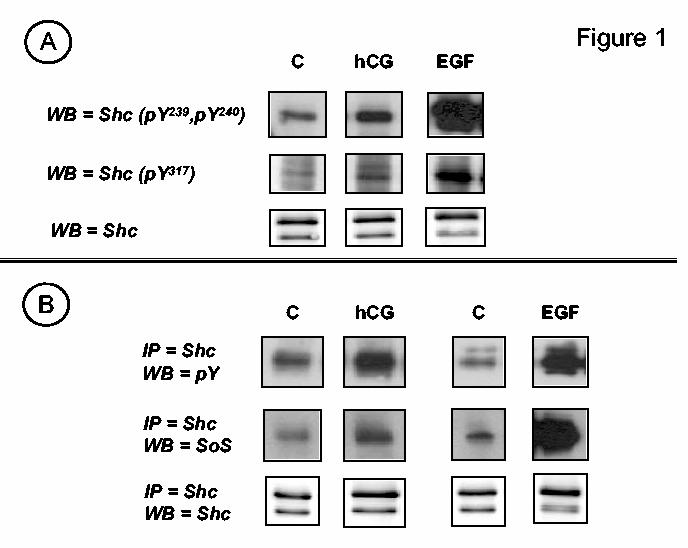

Figure 3.

. Phosphorylation of the EGFR in MA-10 cells MA-10 cells were transfected with the hLHR (1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) and preincubated with DMSO, AG1478 (10 μM) or AG43 (10 μM) for 30 min as indicated. The cells were then incubated with buffer only, hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 15, 15 and 5 min, respectively. Western blots (WB) of whole cell lysates were developed with antibodies that recognize the total EGFR or the EGFR phosphorylated on tyrosine residues 1068 or 1173 as indicated. Only the appropriate areas of the gel of a representative experiment are shown. The signals obtained with EGFR-pY1068 after EGF stimulation appear saturated because the Western blots were exposed for the same length of time to emphasize the difference in the magnitude of the signal detected in cells stimulated with EGF or hCG. Shorter exposures of the western blots of EGFR-pY1068 for EGF treated cells confirmed that AG1478 inhibited the EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation whereas AG43 does not.

The effects of PP2, AG1478 and GM6001 were initially tested using multiple inhibitor concentrations. The concentrations used for the experiments presented here were chosen because they were the minimal concentrations that produce maximal inhibitory effects.

Hormones and supplies

Purified hCG (CR-127, ∼13,000 IU/mg) was purchased from Dr. A. Parlow and the National Hormone and Pituitary Agency of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and purified recombinant hCG1 was provided by Ares Serono (Randolph, MA). Cell culture media was obtained from Invitrogen. Other cell culture supplies and reagents were obtained from Corning. Recombinant EGF was from Sigma (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com). PP1 was purchased from Tocris (http://www.tocris.com) and PP2, PP3, AG1478, AG43 and GM6001 were from Calbiochem (http://www.emdbiosciences.com). All other chemicals were obtained from commonly used suppliers.

Results

Shc is an intermediate in the hCG-induced activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2

The phosphorylation state of Shc in MA-10 cells was ascertained using Western blots probed with antibodies that recognize specific phosphotyrosine residues on Shc or by probing Shc immunoprecipitates with phosphotyrosine antibodies (Figure 1). Both assays revealed that hCG induced a 1.9 ± 0.1-fold increase (mean ± SEM of 23 independent experiments) in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc. This increase is rather small compared to that attained by activation of the endogenous EGFR in MA-10 cells which increased Shc phosphorylation by 16.9 ± 0.5 fold (mean ± SEM of 11 independent experiments). Figure 1A also shows that the hCG-induced increased phosphorylation of Shc occurred mostly on Tyr239 and Tyr240 and to a lesser extent on Tyr317 (25, 28-30) and that this is accompanied by an increase in the levels of complexes containing Shc and Sos2 (Figure 1B). Human CG and EGF induced a 2.3 ± 0.2- and a 37 ± 1-fold increase in the level of complexes containing Shc and Sos (mean ± SEM of 8-9 independent experiments), respectively.

To determine if Shc is an intermediate in the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 we transiently transfected MA-10 cells with a Shc-glutathione-S-transferase fusion protein in which the three main phosphorylation sites of Shc (Tyr239, Tyr240 and Tyr317) were mutated to phenylalanines (25, 28-30). This construct has been previously shown to exhibit dominant-negative behavior in other cells (25, 29, 30), it can be easily distinguished from endogenous Shc because of its higher molecular weight and it is expressed at a higher level than endogenous Shc when transfected into MA-10 cells (Figure 2A).

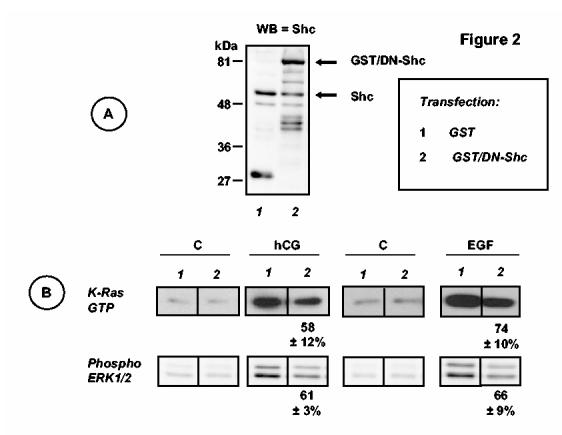

Figure 2.

. Dominant-negative Shc inhibits the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 stimulated by hCG or EGF. MA-10 cells were co-transfected with the hLHR and a GST expression vector or the hLHR and an expression vector for the dominant-negative Shc/GST fusion protein (each used at 1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) as indicated. Cells were incubated with buffer only (C), or hCG (100 ng/ml) for 15 min or with buffer only (C) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 5 min as indicated. Panel A. Western blots (WB) of whole cell lysates from the cells incubated with buffer only were developed using antibodies to Shc as described in Materials and Methods. The entire blots are shown and the results are representative of three independent experiments. Molecular weight markers are shown on the left and the arrows on the right indicate the positions of endogenous Shc, and the GST/DN-Shc fusion protein. We did not try to identify the lower molecular weight bands recognized by the Shc antibody in the two extracts. Panel B. Lysates were prepared and used to measure active Ras or phosphorylated ERK1/2 as described in Materials and Methods. Only the appropriate areas of the gel or a representative experiment are shown. The numbers shown at the bottom of the hCG or EGF stimulated blots show percentages of the responses of cells transfected with GST/DN-Shc relative to their respective controls (i.e., stimulated cells transfected with GST) and they represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The magnitudes of the signals shown for the hCG- and EGF-stimulated cells should not be compared because the western blots shown were not exposed for the same length of time.

In agreement with previous data (9), the results presented in Figure 2B show that hCG and EGF increase the levels of active Ras 2.3 ± 0.2 and 12.1 ± 0.6-fold over basal, respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 15-18) and phospho-ERK1/2 5.1 ± 0.1 and 7.4 ± 0.3, respectively (mean ± SEM, n =28-29). Transient transfection of MA-10 cells with the dominant-negative Shc inhibited hCG- and EGF-induced Ras activation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation by 26-42% as detailed in Fig 2.

Human CG enhances the phosphorylation of the EGF receptor.

A prominent mechanism by which G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate the ERK1/2 cascade is by stimulating the release of a heparin-bound form of EGF which then activates the EGFR in a paracrine/autocrine fashion (17, 31-34). To determine if this pathway is operative when MA-10 cells are stimulated with hCG we examined the phosphorylation state of the endogenous EGFR on Tyr1068, and Tyr1173 after hCG or EGF stimulation. These residues were chosen because they serve as docking sites for Grb2 and Shc, respectively, the two adaptor proteins that participate in the EGF-induced activation of the Ras-ERK1/2 cascade (17, 18, 32, 33, 35).

Figure 3 shows that basal phosphorylation of EGFR-Tyr1068 is readily detectable but basal phosphorylation of EGFR-Tyr1173 is not. EGF increased the phosphorylation of these two residues 20-50 fold-over basal but hCG increased only the phosphorylation of EGFR-Tyr1068 (1.47 ± 0.06-fold over basal, n =14). The data presented in Figure 3 also show that the phosphorylation of these two residues is dependent on the kinase activity of the EGFR because they can be inhibited by AG1478 (a selective inhibitor of the EGFR kinase) but not by AG43, its inactive analog (36). Lastly, it should be noted that the EGF-induced increase in the phosphorylation of the EGFR was accompanied by an apparent decrease in the total amount of EGFR but such decrease was not detectable in hCG stimulated cells (Figure 3). The reasons for this decrease were not investigated but is either due to an increase in the degradation of the EGFR that accompanies activation (32) or it could simply be due to a phosphorylation-dependent masking of the epitopes recognized by the EGFR antibody used (see Materials and Methods).

The effects of hCG on the EGFR, Shc, Ras and ERK1/2 are mediated by SFKs.

Since we have recently shown that hCG can activate SFKs in MA-10 cells (10) and since SFKs can phosphorylate Shc (28) and the EGFR (22) we next tested for the involvement of SFKs and the EGFR on the hCG-induced activation of the Ras-ERK1/2 cascade.

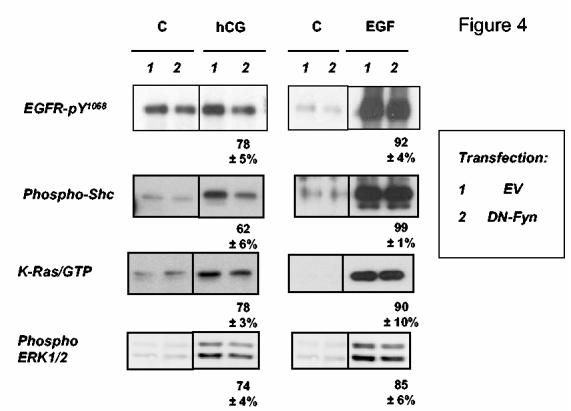

We first examined the effects of overexpression of a dominant-negative (i.e., kinase-deficient) Fyn on the activation of key steps of this pathway by hCG or EGF (Figure 4). Dominant-negative Fyn did not inhibit the effects of EGF on the phosphorylation of the EGFR3 or Shc, the activation of Ras, or on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. In contrast, expression of the dominant-negative Fyn had an inhibitory effect on all these steps when stimulated by hCG (Figure 4). A dominant-negative mutant of Yes (the other SFK expressed in MA-10 cells) was not tested because this mutant was previously shown to be an ineffective inhibitor of other SFK-mediated actions in MA-10 cells (10).

Figure 4.

. Dominant-negative Fyn inhibits the hCG-induced activation of pathways leading to the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. MA-10 cells were co-transfected with an empty vector (EV) and the hLHR or the expression vector for the dominant-negative Fyn and the hLHR (each used at 1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) as indicated. Cells were incubated with buffer only (C), or with hCG (100 ng/ml) for 15 min or with buffer only (C) or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 5 min. Lysates were prepared and used to measure the phosphorylated EGFR, phospho-Shc, activated K-Ras and phospho-ERK1/2 as indicated. Only the appropriate areas of the gel of a representative experiment are shown. The numbers shown at the bottom of the hCG or EGF stimulated blots show percentages of the responses of cells transfected with DN-Fyn relative to their respective controls (i.e., stimulated cells transfected with EV) and they represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The magnitude of some of the signals obtained after EGF stimulation appear saturated because the Western blots were exposed for the same length of time to emphasize the difference in the magnitude of the signal detected in cells stimulated with EGF or hCG. Shorter exposures of these blots were used for quantitation. Note that the expression of the transfected dominant-negative Fyn has been previously documented (10).

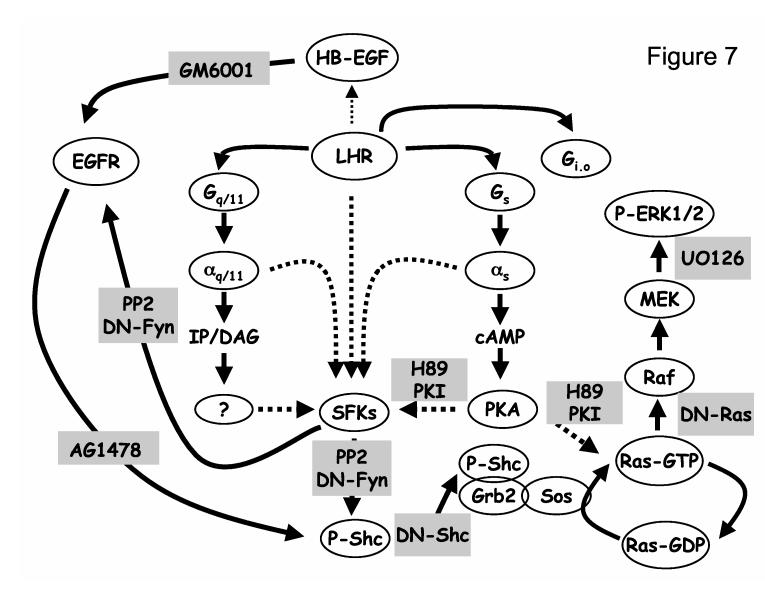

We next examined the effects of a selective inhibitor of the SFKs and its inactive analog (PP2 and PP3, respectively see refs. 37, 38), a selective inhibitor of the EGFR kinase and is inactive analog (AG1478 and AG43, respectively, see ref. 36) and GM6001, a broad spectrum metalloprotease inhibitor that blocks the release of the heparin-bound form of EGF (39). These inhibitors were tested on the phosphorylation of EGFR and Shc, the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 when activated by hCG or by EGF (Figure 5). A comparison of the effects of PP2 on the actions of hCG (top left panel of Figure 5) and EGF (bottom left panel of Figure 5) clearly show that PP2 is effective against hCG but not against EGF. Note also that PP2 is least effective on the hCG-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR (∼25% inhibition) and most effective on the hCG-induced activation of Ras and phospho-ERK1/2 (≥ 50% inhibition). In contrast, AG1478 blocks all the actions of EGF by ≥ 90% (bottom middle panel of Figure 5) and it inhibits many of the actions of hCG but to a lesser extent (top middle panel of Figure 5). The inhibitory effect of AG1478 is particularly evident on the hCG-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR and the activation of Ras and it is less evident on the phosphorylation of Shc and ERK1/2 (top middle panel of Figure 5). Importantly, the inactive compounds used as negative controls (AG43 and PP3) are indeed unable to inhibit any of the aforementioned effects. GM6001 has no effect on any of the actions of EGF (bottom right panel of Figure 5) and it does not inhibit the hCG-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR or ERK1/2 (top right panel of Figure 5). It does, however, cause a ≥ 25% inhibition of the hCG-provoked phosphorylation of Shc and the activation of Ras (top right panel of Figure 5). We did not seek an explanation for these two inhibitory effects of GM6001 but obviously they are unrelated to an inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation. Moreover, the slightly different pattern of the inhibitory effects of GM6001 on the actions of hCG and EGF on this cascade provide additional evidence for our contention that EGF-like factors are not mediators of the actions of hCG (see below).

Figure 5.

. SFK and EGFR kinase inhibitors abrogate the hCG-induced activation of pathways leading to the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. MA-10 cells were transfected with the hLHR (1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well) and preincubated with DMSO (control) or with PP2, PP3, AG1478, AG43 (all dissolved in DMSO and added at a final concentration of 10 μM) or GM6001 (also dissolved in DMSO but added at a final concentration of 20 μM) for 30 min as indicated. The cells were then incubated with 100 ng/ml hCG (top panels) for 15 min or with 100 ng/ml EGF for 5 min. The phosphorylation of the EGFR (on Y1068) and Shc, the activation or Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments where the data obtained with the indicated inhibitors are expressed as a percent of their respective controls (i.e., stimulated cells incubated with DMSO).

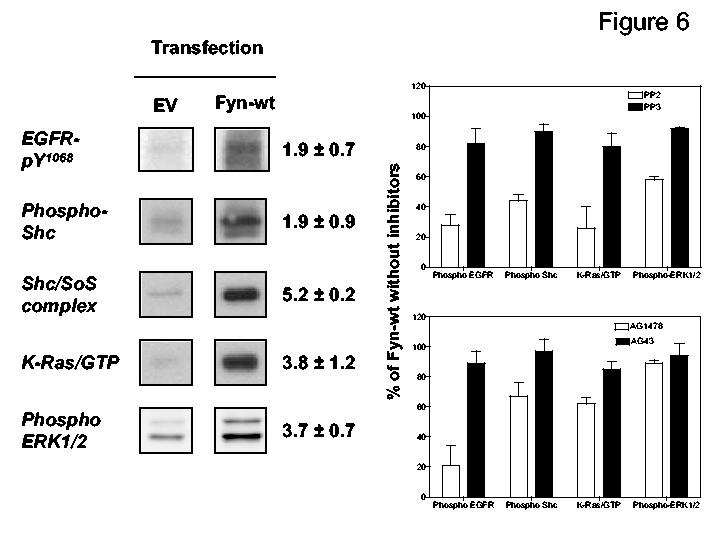

Lastly, we tested if overexpression of Fyn recapitulated the actions of hCG and EGF on this tyrosine kinase cascade and if these actions were blocked by AG1478 or PP2. The data presented in Fig 6 show that Fyn overexpression in MA-10 cells enhances the phosphorylation of the EGFR and Shc, the formation of Shc/Sos complexes, the activation of Ras and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. These results also show that PP2 (but not PP3) inhibits all of these Fyn-mediated events by ≥40%. AG1478 also inhibits the effects of Fyn on the phosphorylation of the EGFR and Shc as well as on Ras activation but is ineffective on the Fyn-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

. Expression of Fyn in MA-10 cells activates tyrosine kinase cascades leading to the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. MA-10 cells were transfected with an empty vector (EV) or with an expression vector for Fyn (each at 1 μg of plasmid /35 mm well). The cells were then incubated with DMSO (control) or with PP2, PP3, AG1478, AG43 (all dissolved in DMSO and added at a final concentration of 10 μM) for 30 min. Lysates were prepared and used to measure EGFR-pY1068, phospho-Shc, Shc/Sos complexes, activated K-Ras and phospho-ERK1/2 as indicated. On the left only the appropriate areas of the gel are shown. The numbers shown represent the fold increase (mean ± SEM of three independent transfections) for each parameter measured in the Fyn-wt transfected cells relative to those transfected with empty vector. On the right each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments where the data obtained with the Fyn-transfected cells incubated with the indicated inhibitors are expressed as a percent of the Fyn-transfected cells incubated with DMSO. Note that the expression of the transfected Fyn has been previously documented (10).

These data suggest that Fyn can activate this tyrosine kinase cascade by directly phosphorylating Shc and also indirectly through a Fyn-provoked phosphorylation of the EGFR. Alternatively, it is possible that the phosphorylation of Shc is directly mediated by Fyn and that AG1478 is an inhibitor of Fyn. We cannot distinguish between these two possibilities.

Discussion

We show here that hCG induces the phosphorylation of Shc on Tyr239/Tyr240 (and perhaps Tyr317) and the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos in MA-10 cells. These findings are important for two reasons. First, they provide novel evidence to further support the conclusion that hCG stimulates tyrosine kinase cascades in MA-10 cells (10). Second, since Sos is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras (11-16, 22, 28, 40, 41) our results raise the possibility that Shc and Sos are intermediates in the pathway by which hCG activates the Ras/ERK1/2 cascade (9). The involvement of phosphorylated Shc in these actions of hCG is, in fact, supported by the finding that a dominant-negative mutant of Shc can inhibit the effects of hCG on Ras activation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The magnitude of the inhibitory effect of the dominant-negative Shc is less than 50% but is similar when MA-10 cells are stimulated with either hCG or with EGF. This serves as an important positive control because Shc phosphorylation is known to be required for the EGF-induced activation of the Ras-ERK1/2 cascade (17, 18, 32, 33, 35). The relatively small magnitude of the inhibitory effects of the dominant-negative Shc (or other dominant-negative constructs, see below) is likely to be due to the efficiency of our transient transfections, which is about 25% (23). The use of MA-10 cells stably expressing the dominant-negative Shc may result in a more quantitative inhibition of these pathways but we have been unable to select stable MA-10 transfectants expressing this construct.

The tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos can be provoked by activation of receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (11-16, 22, 28, 40, 41), and one or both of these could mediate the effects of hCG on Shc phosphorylation.

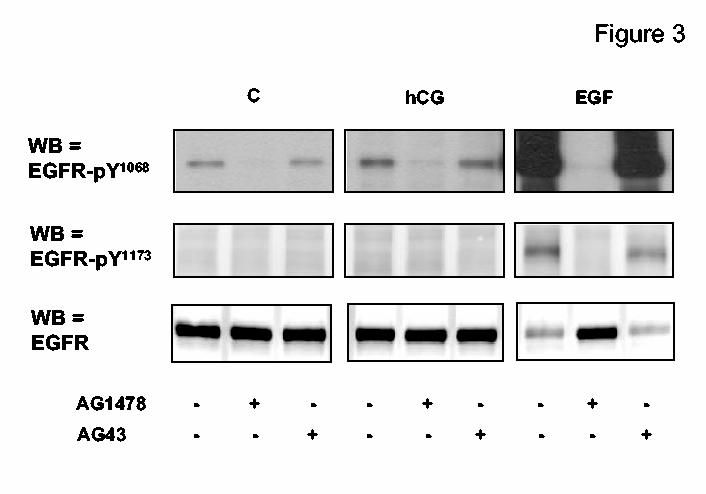

MA-10 cells express EGF receptors endogenously, and addition of EGF induces a pronounced increase in the phosphorylation of Tyr1068 and Tyr1173 of the EGFR. Activation of the EGFR then results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc, the formation of protein complexes containing Shc and Sos, the activation of Ras, and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. All of these are dependent on the kinase activity of the EGFR as judged by their sensitivity to AG1478 but they are independent of SFKs as judged by their insensitivity to PP2 and to DN-Fyn. In addition, DN-Shc inhibits the EGF-induced activation of Ras and ERK1/2. Therefore, the pathway used by EGF to activate Ras and ERK1/2 in MA-10 cells is the same pathway that has been so well described in other cell types (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

. Pathways by which the LHR activates the Ras-ERK1/2 cascade in MA-10 cells. The LHR activates Gs, Gi/o and Gq/11 in MA-10 cells (46) but the LHR-induced activation of the SKFs appears to involve only the activation of Gs, and Gq/11 (10). SFKs can be activated through kinases or other effectors stimulated by second messengers generated in response to αs, and αq/11. The effectors that may mediate the effects of inositol phosphates/diacylglycerol (IP/DAG) are not known and are depicted by a question mark, but the cAMP effects are mediated by PKA rather than cAMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factors (10). Since it is not known if the PKA-dependent activation of the SFKs is direct or indirect this is depicted by a broken arrow. SFKs could also be directly activated by αs, αq/11 and/or the LHR (10). These putative pathways are also indicated with broken arrows. Activated SFKs mediate the phosphorylation of Shc leading to the formation of complexes containing Shc and Sos and presumably Grb2 as shown. Sos then promotes the exchange of GDP for GTP in Ras and the GTP-bound Ras activates the Raf-MEK-ERK1/2 cascade. It is also possible that PKA can indirectly activate Ras by phosphorylation of a Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor or a Ras GTPase as depicted by the broken arrow. The EGF receptor can directly phosphorylate Shc as shown previously by many investigators (17, 31-34, 52) and it may be a mediator of the hCG-induced phosphorylation of Shc because it can be phosphorylated and activated by SFKs as shown. The gray boxes show where these pathways can be inhibited either by DN mutants or by pharmacological inhibitors as documented here and elsewhere (10, 46). The results presented here support the hypothesis that the LHR-provoked phosphorylation of Shc is directly mediated by the SFKs and also indirectly by an SFK-dependent activation of the EGFR. The LHR does not appear to induce an autocrine transactivation of the EGFR in MA-10 cells.

When added to MA-10 cells hCG activates SFKs (10) and it enhances the phosphorylation of EGFR-Tyr1068. Since Shc can be phosphorylated by the SFKs or by the EGFR kinase (28), the enhanced phosphorylation of Shc induced by hCG can be directly mediated by the SFKs or by the activated EGFR (Figure 7). The hCG-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR could in turn be mediated by an extracellular autocrine pathway involving the hCG-induced release of EGF-like growth factors which then activate the EGFR (17, 31-34). Alternatively, the hCG-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR could be mediated by the activated SFKs (10), which are known to phosphorylate the EGFR and to promote its activation (22, 41).

Since the hCG-provoked phosphorylation of the EGFR is not inhibited by GM6001, we conclude that it is not mediated by the release of EGF-like growth factors. In all likelyhood the hCG-provoked phosphorylation of the EGFR is mediated by the SFKs and the EGFR kinase because it is inhibited by PP2, DN-Fyn and AG1478 (Figure 7). The sensitivity of the hCG-induced Shc phosphorylation to PP2, DN-Fyn and AG1478 supports the conclusion that the hCG-provoked phosphorylation of Shc is directly and indirectly mediated by the SFKs. The direct effect of SFKs on Shc phosphorylation is likely to be a simple catalytic event because the SFKs catalyze the phosphorylation of Shc on Tyr239 and Tyr240 and Tyr317, the same tyrosine residues phosphorylated by receptor tyrosine kinases (28). The indirect effect on the other hand is likely to be a catalytic event mediated by the activated EGFR kinase, which is activated in response to an SFK-catalyzed phosphorylation (Figure 7).

When considered together, the inhibitor data and the relatively weak phosphorylation of the EGFR induced by hCG support the notion that the direct phosphorylation of Shc by the SFKs is likely to be the most important component. This contention is further supported by the finding that hCG does not appear to increase the phosphorylation of EGFR-Y1173 which is the most prominent Shc binding residue of the EGFR (17, 18, 32, 33, 35). If Shc does not bind to the phosphorylated EGFR in response to hCG activation then one must also ask the question of how the phosphorylated Shc may dock to cell membranes in order to bring Sos in close proximity to Ras. Although we do not have a definite answer for this question we note that SFKs phosphorylate a number of other membrane associated proteins such as FAK (42, 43) and Srcasm (44, 45) that can provide a docking site for the phosphorylated Shc.

The data presented here as well as our previous studies (9, 10) start to define the pathways by which the LHR activates Ras and the ERK1/2 cascade in MA-10 cells as summarized in Figure 7. We know that the LHR activates Gs, Gi/o and Gq/11 in MA-10 cells (46) and that the simultaneous activation of Gs and Gq/11 may be needed to stimulate the activity of SFKs (10). Although the SFKs can be activated by the second messengers generated by each of these activated G proteins, it is also possible that they can be directly activated by the liberated Gα subunits and/or by the LHR (broken arrows in Figure 7 and ref. 10). The cAMP-induced activation of SFKs appears to be mediated by PKA rather than the cAMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factors as judged by the effects of selective cAMP analogs (10). The activation of the SFKs results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of other prominent proteins such as FAK and paxillin (10). As shown here the activated SFKs promote the phosphorylation of Shc directly and indirectly through the phosphorylation and activation of the EGFR (Figure 7). The phosphorylation of Shc leads to the formation of protein complexes containing Shc and Sos. Sos then activates Ras by promoting the exchange of the bound GDP for GTP and the activated Ras stimulates the Raf-MEK-ERK1/2 cascade (Figure 7). We have not formally shown the involvement of Sos on the hCG-induced activation of the Ras-ERK1/2 cascade, but the involvement of Shc, cAMP, PKA, Ras and MEK on this pathway have been documented here or elsewhere (9) by using dominant-negative mutants or pharmacological inhibitors as summarized in Figure 7. The strong inhibition of the hCG-induced Ras activation detected when MA-10 cells are incubated with PP2 underscores the importance of SFKs on this pathway. The hCG-induced activation of Ras is also PKA-dependent (Figure 7 and ref. 9) but it remains to be determined if PKA and SFKs activate Ras in a coordinate or independent fashion. PKA and SFKs may also contribute to ERK1/2 phosphorylation by acting beyond Ras activation but this pathway is not shown in Fig 7 for simplicity. The finding that some of the inhibitors used here are more effective on Ras activation than on ERK1/2 phosphorylation suggests that this additional pathway needs to be further investigated.

These and previous studies on the activation of Ras (9) and tyrosine kinase cascades (10) in MA-10 cells begin to set up the foundation for the study of mitogenic pathways that may be involved in the proliferation of Leydig cells. The obvious overlap in some of the signaling cascades stimulated by hCG and EGF documented here may provide an explanation for our old studies showing that EGF and hCG have similar as well as divergent effects of several aspects of the differentiated functions of MA-10 cells such as cAMP accumulation, steroid synthesis and the regulation of the endogenous LHR (reviewed in ref. 47). Interestingly a recent study showed that the steroidogenic response of MA-10 cells to LH is sensitive to AG1478 but not to GM6001 (48). These results parallel the data presented here on the effects of these two inhibitors on other hCG- and EGF-mediated cascades.

Lastly, our results complement other recent studies by different investigators that have highlighted the involvement of tyrosine kinase cascades in the actions of LH (49, 50) and FSH (51) in ovarian target cells. For example, injection of hCG has been reported to rapidly increase the tyrosine phosphorylation of some members of the Janus family of kinases, the signal transduction and activators of transcription, the insulin receptor substrate and Shc in ovarian follicles (49). The mechanisms by which these events are stimulated were not investigated, however (49). Other studies have documented that FSH, acting through a cAMP/PKA-dependent pathway, rapidly activates an ovarian phosphotyrosine phosphatase that dephosphorylates ERK1/2 (51) whereas hCG, acting in a much slower fashion increases the expression and/or processing of members of the EGF family of growth factors in the ovary and these in turn transactivate the EGFR in granulosa cells (50). Together these results as well as those presented here show that the LHR (and perhaps the FSHR) can use multiple mechanisms to activate tyrosine kinase cascades in their ovarian and testicular target cells.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-40629).

Both preparations were used in this study and were found to be indistinguishable

We do not imply a direct association between Shc and Sos. In fact this association is known to occur indirectly through Grb2. We simply did not test for the presence of Grb2 in the Shc immunoprecipitates because we believe this to be a foregone conclusion.

In this and subsequent experiments we chose to investigate only the phosphorylation of Tyr1068 of the EGFR because this is the only phosphorylation event enhanced by EGF and hCG (c.f. Figure 3).

References

- 1.Christensen AK, Peacock KC. Increase in Leydig cell number in testes of adult rats treated chronically wtih an excess of human chorionic gonadotropin. Biol Reprod. 1980;22:381–391. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor. A. 2002;2002:141–174. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Themmen APN. An update of the pathophysiology of human gonadotrophin subunit and receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms. Reproduction. 2005;130:263–274. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F-P, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. Normal Prenatal but Arrested Postnatal Sexual Development of Luteinizing Hormone Receptor Knockout (LuRKO) Mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:172–183. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei ZM, Mishra S, Zou W, Xu B, Foltz M, Li X, Rao CV. Targeted Disruption of Luteinizing Hormone/Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Receptor Gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:184–200. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar TR. What have we learned about gonadotropin function from gonadotropin subunit and receptor knockout mice. Reproduction. 2005;130:293–302. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rulli SB, Huhtaniemi I. What have gonadotrophin overexpressing transgenic mice taught us about gonadal function. Reproduction. 2005;130:283–291. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huhtaniemi IT, Rullin S, Ahtiainen P, Poutanen M. Multiple sites of tumorigenesis in transgenic mice overproducing hCG. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;234:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR)-induced phosphorylation of the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) in Leydig cells is mediated by a protein kinase A-dependent activation of Ras. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2189–2200. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizutani T, Shiraishi K, Welsh T, Ascoli M. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) by a pathway that involves Src family kinases. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:619–630. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock JF. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen PJ, Lockyer PJ. Integration of calcium and ras signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1038/nrm808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stork PJS, Schmitt JM. Crosstalk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell prolifration. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donward J. Targeting Ras signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nature Reviews in Cancer. 2002;3:11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repasky GA, Chenette EJ, Der CJ. Renewing the conspiracy theory debate: does Raf function alone to mediate Ras oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holbro T, Hynes NE. ERBB receptors: Directing Key Signaling Networks Throughout Life. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:195–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinelle N, Holst M, Soder O, Svechnikov K. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases Are Involved in the Acute Activation of Steroidogenesis in Immature Rat Leydig Cells by Human Chorionic Gonadotropin. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4629–4634. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron M, Foster J, Bukovsky A, Wimalasena J. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by gonadotropins and cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphates in porcine granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:111–119. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seger R, Hanoch T, Rosenberg R, Dantes A, Merz WE, Strauss JF, III, Amsterdam A. The ERK Signaling Cascade Inhibits Gonadotropin-stimulated Steroidogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13957–13964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bromann PA, Korkaya H, Courtneidge SA. The interplay between Src family kinases and receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23:7957–7968. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirakawa T, Galet C, Ascoli M. MA-10 cells transfected with the human lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (hLHR). A novel experimental paradigm to study the functional properties of the hLHR. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1026–1035. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resh MD. Fyn, a Src family tyrosine kinase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:1159–1162. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratt JC, van den Brink MRM, Igras VE, Walk SF, Ravichandran KS, Burakoff SJ. Requirement for Shc in TCR-Mediated Activation of a T Cell Hybridoma. J Immunol. 1999;163:2586–2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ascoli M. Characterization of several clonal lines of cultured Leydig tumor cells: gonadotropin receptors and steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology. 1981;108:88–95. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Triest M, Bos JL. Pull-down assays for guanoside 5′-triphosphate-bound Ras-like guanosine 5′-triphosphatases. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;250:97–102. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-671-1:97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Geer P, Wiley S, Gish GD, Pawson T. The Shc adaptor protein is highly phosphorylated at conserved, twin tyrosine residues (Y239/240) that mediate protein-protein interactions. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1435–1444. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Lorenz U, Ravichandran KS. Role of Shc in T-cell development and function. Immunol Rev. 2003;191:183–195. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song RX-D, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, Santen RJ. Linkage of Rapid Estrogen Action to MAPK Activation by ER{alpha}-Shc Association and Shc Pathway Activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:116–127. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce KL, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. New mechanisms in heptahelical receptor signaling to mitogen protein kinase cascades. Oncogene. 2001;20:1532–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter G. Employment of the epidermal growth factor receptor in growth factor-independent signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:697–702. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hackel PO, Zwick E, Prenzel N, Ullrich A. Epidermal growth factor receptors: critical mediators of multiple receptor pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:184–189. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh M, Conti M. G-protein-coupled receptor signaling and the EGF network in endocrine systems. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2005;16:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaffe MB. Phosphotyrosine-binding domains in signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:177–186. doi: 10.1038/nrm759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence DS, Niu J. Protein kinase inhibitors: the tyrosine-specific protein kinases. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:81–114. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanke JH, Gardner JP, Dow RL, Changelian PS, Brissette WH, Weringer EJ, Pollok BA, Connelly PA. Discovery of a Novel, Potent, and Src Family-selective Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Bishop A, Witucki L, Kraybill B, Shimizu E, Tsien J, Ubersax J, Blethrow J, Morgan DO, Shokat KM. Structural basis for selective inhibition of Src family kinases by PP1. Chem Bio. 1999;6:671–678. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown S, Meroueh SO, Fridman R, Mobashery S. Quest for selectivity in inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;4:1227–1238. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjorge JD, Jakymiw A, Fujita DJ. Selected glimpses into the activation and function of Src kinase. Oncogene. 2000;19:5620–5635. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roskoski R., Jr. Src kinase regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parsons TJ. Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1409–1416. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Marshall C, Mei L, Dzubow L, Schmults C, Dans M, Seykora J. Srcasm modulates EGF and Src-kinase signaling in keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6036–6046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seykora JT, Mei L, Dotto GP, Stein PL. ‘Srcasm: a novel Src activating and signaling molecule. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2812–2822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. A constitutively active somatic mutation of the human lutropin receptor found in Leydig cell tumors activates the same families of G proteins as germ line mutations associated with Leydig cell hyperplasia. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3872–3878. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ascoli M, Segaloff DL. Regulation of the differentiated function of Leydig tumor cells by epidermal growth factor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;564:99–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb25891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamnongjit M, Gill A, Hammes SR. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling is required for normal ovarian steroidogenesis and oocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2005;102:16257–16262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508521102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carvalho CRO, Carvalheira JBC, Lima MHM, Zimmerman SF, Caperuto LC, Amanso A, Gasparetti AL, Meneghetti V, Zimmerman LF, Velloso LA, Saad MJA. Novel Signal Transduction Pathway for Luteinizing Hormone and Its Interaction with Insulin: Activation of Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription and Phosphoinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathways. Endocrinology. 2003;144:638–647. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J-Y, Su Y-Q, Ariga M, Law E, Jin SLC, Conti M. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. Science. 2004;303:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.1092463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cottom J, Salvador LM, Maizels ET, Reierstad S, Park Y, Carr DW, Davare MA, Hell JW, Palmer SS, Dent P, Kawakatsu H, Ogata M, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Follicle-stimulating Hormone Activates Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase but Not Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase Kinase through a 100-kDa Phosphotyrosine Phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7167–7179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203901200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luttrell DK, Luttrell LM. Not so strange bedfellows: G-protein-coupled receptors and Src family kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23:7969–7978. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]