Abstract

Oxazolomycin (OZM), a hybrid peptide-polyketide antibiotic, exhibits potent antitumor and antiviral activities. Using degenerate primers to clone genes encoding methoxymalonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) biosynthesis as probes, a 135-kb DNA region from Streptomyces albus JA3453 was cloned and found to cover the entire OZM biosynthetic gene cluster. The involvement of the cloned genes in OZM biosynthesis was confirmed by deletion of a 12-kb DNA fragment containing six genes for methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis from the specific region of the chromosome, as well as deletion of the ozmC gene within this region, to generate OZM-nonproducing mutants.

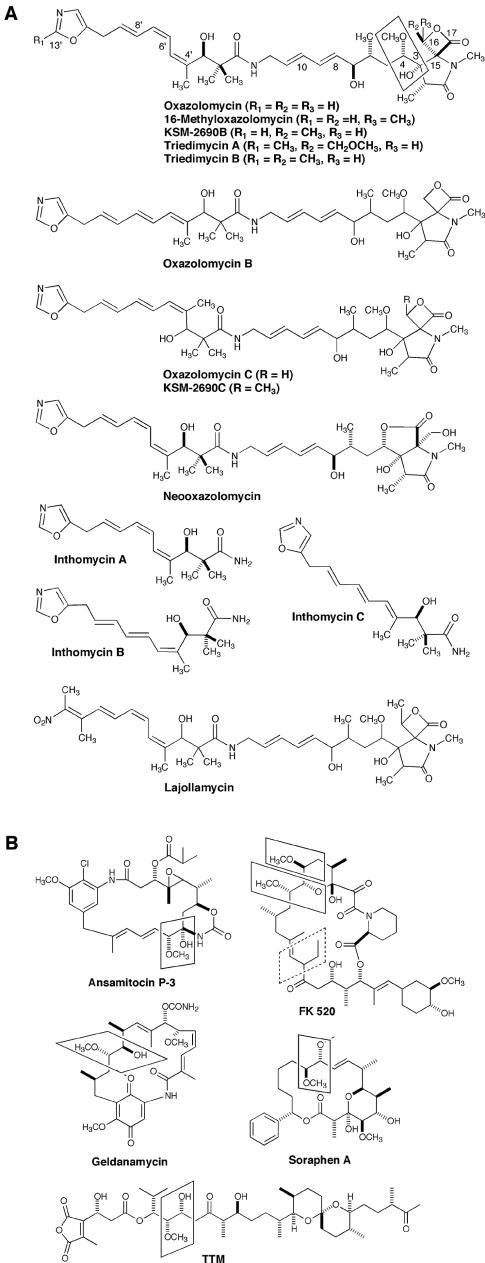

The oxazolomycins (OZMs) are a family of antibiotics produced by several Streptomyces species. OZM, produced by Streptomyces sp. KBFP-2025 and Streptomyces albus JA3453, is structurally characterized by a unique spiro-linked β-lactone/γ-lactam moiety, a 5-substituted oxazole ring, an (E, E)-diene, and a (Z, Z, E)-triene chain (7, 13) (Fig. 1A). OZM B and C, produced by S. albus, are geometrical isomers of OZM which differ in the configuration of the triene moiety, which is E, E, E for OZM B and Z, E, E for OZM C (7). Other members of this family include 16-methyloxazolomycin KSM-26908, KSM-20906 (17), triedimycin A and B (5) (also known as curromycins from a genetically modified strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus [15, 16]), neooxazolomycin (24), inthomycins A, B, and C (4) (also known as phthoxazolins [23]), and lajollamycin (12) (Fig. 1A). These compounds have antitumor and antiviral but limited antibacterial activities. The triedimycins were shown in one study to have an antiviral activity comparable to that of zidovudine, representing one of a few natural products known to date as human immunodeficiency virus inhibitors (14).

FIG. 1.

(A) Structures of oxazolomycin and related natural products and (B) selected examples of natural products that utilize methoxymalonate as a biosynthetic precursor. The methoxymalonate-derived moiety is highlighted (box). TTM, tautomycin.

The results of isotope-labeling experiments (2) have shown that the carbon backbone of OZM is derived from three molecules of glycine and nine molecules of acetate, with all of the five C-methyl groups, one O-methyl group, and one N-methyl group originating with methionine. The origin of the C3—C4 unit and the C16 and C13′ carbons of OZM remains unknown (Fig. 1A). Hence, it appears that OZM biosynthesis has the following novel features: (i) hybrid nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-polyketide synthase (PKS) biosynthetic machinery that initiates peptide-polyketide biosynthesis with an oxazole moiety, elongates the peptide-polyketide chain by transitioning between NRPS-PKS four times, and terminates the peptide-polyketide synthesis with a β-lactone/γ-lactam structure; (ii) a modular PKS that introduces all five of the C-methyl groups by choosing malonyl coenzyme A (CoA) as a chain extender followed by C methylation instead of using methylmalonyl CoA; (iii) specific control of double-bond geometry by the modular PKS to create the unique (Z, Z, E)-triene and (E, E)-diene; and (iv) introduction of the C16 and C13′ carbons, which is expected to require novel chemistry by the PKS or NRPS.

Although the isotope-labeling experiments had failed to establish the biosynthetic origin of the C3—C4 unit of OZM, similar moieties are present in several other polyketide natural products, such as ansamitocins P-3 (28), FK520 (27), geldanamycin (20), soraphen (10, 29), and tautomycin (9) (Fig. 1B). Chemical, biochemical, and genetical investigations of the biosynthesis of these metabolites have established that this unit is derived from an intermediate of the glycolytic pathway, which is used to form methoxymalonyl-ACP as an extender unit. Five genes typically are involved (9, 10, 20, 27-29), and the structure of FkbI, the acyl-ACP dehydrogenase for methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis from the FK520 biosynthetic pathway, supports the preferred substrate specificity for an acyl-ACP instead of an acyl CoA (26).

The OZM molecular scaffold is an excellent lead for drug discovery by combinatorial biosynthesis due to its promising biological activities (14, 12). As the first step towards this goal, we report here a PCR method to clone the ozm methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic locus from S. albus JA3453 and its use to clone the entire ozm biosynthetic cluster. The ozm methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic locus was also characterized by gene replacement and complementation, to establish the biosynthetic origin of the C3—C4 moiety of OZM.

Cloning of the methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis locus from S. albus JA3453.

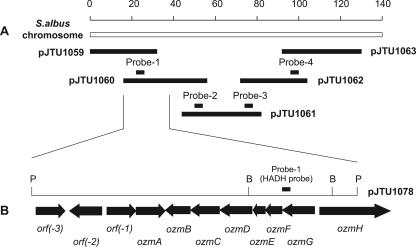

Degenerate primers (HADH-FP [5′-GTC CTG GGC GCC GGS GTS ATG GG-3′] and HADH-RP [5′-GTT GTC CAG GCC GAT SAG GTC NGC-3′]) were designed according to two conserved regions (VLGAGVMG and ADLIGLDN) of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenases (HADHs) known for methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis (9, 10, 20, 27-29) and used to amplify putative HADH genes by PCR from S. albus JA3453 total DNA using conditions suitable for the GC-rich DNA (8). A distinct product with the predicted size of 0.73 kb was amplified, cloned into pGEM-EZ (Promega, Madison, WI) as pJTU1051, and sequenced. The deduced 228 amino acids showed high sequence homology to Asm13 (59% identity), a known HADH characterized from the ansamitocin biosynthesis gene cluster (28). This HADH fragment was then used as a probe to screen the S. albus JA3453 genomic library prepared in pOJ446 (8) by standard methods (8, 21). Of the 3,000 colonies screened by colony hybridization, four overlapping cosmids, as represented by pJTU1059 and pJTU1060, were identified and confirmed by PCR and Southern hybridization to contain the 4.5-kb BglII fragment that includes the HADH probe (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

(A) A 135-kb contiguous DNA from S. albus JA3453 covering the entire ozm gene cluster as represented by five overlapping cosmid clones. Probes used to clone and map the ozm gene cluster are designated Probe-1, -2, -3, and -4. (B) Genetic organization of the ozm methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic locus identified within the sequenced 12.2-kb PvuII fragment. B, BglII; P, PvuII.

Genes encoding acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ADHs) have been clustered, without exception, with those encoding HADHs within all methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis loci characterized to date. Degenerate primers (ADH-FP [5′-CAG GGC ATG GCC GCS TGG ACS GT-3′] and ADH-RP [5′-GCA GGC GCG CAG GAT SCC SAC RCA-3′]) were similarly designed according to two conserved regions (QGMVVWTV and CVGILRAC) of ADHs from known methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis loci (9, 10, 20, 27-29) and used to examine the four HADH-positive cosmids by PCR for the presence of an ADH gene. A distinct product with the predicted size of 0.5 kb was readily amplified from pJTU1059 and cloned (pJTU1052), whose identity as an ADH gene was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Confirmation of the cloned HADH/ADH locus is essential for OZM biosynthesis.

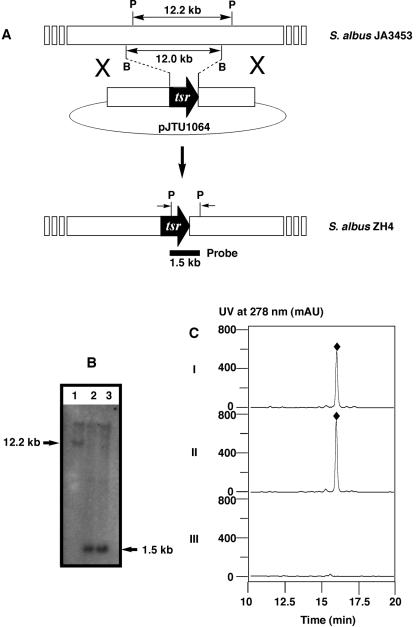

To confirm that the cloned locus encodes OZM biosynthesis genes, a 12-kb BglII fragment internal to pJTU1059 was replaced with the 1.1-kb thiostrepton (tsr) resistance (Thir) gene, suitable for selection in Streptomyces, to yield pJTU1064 (Fig. 3A). Introduction of pJTU1064 into S. albus JA3453 by conjugation with Thir selection, using published protocols (8, 21) with genetic methods we developed for JA3453 (unpublished work), yielded exconjugants at a frequency of about 10−5 exconjugants per donor. Since pJTU1064 contains the SCP2* origin of replication that is functional but unstable in most Streptomyces strains (8), exconjugates that were also apramycin resistant (Aprr) most likely had pJTU1064 integrated into the S. albus JA3453 chromosome via a single-crossover homologous recombination event. Such Thir and Aprr colonies were further screened on mannitol soy flour (MS) medium (8) for the Thir and Aprs phenotype. Approximately 1% of the colonies examined were Aprs, due to loss of the SCP2*-derived vector part of pJTU1064 as the result of the second crossover homologous recombination event (Fig. 3A). This genotype was confirmed for two of the Thir and Aprs isolates by Southern analysis, in which a distinctive band at 12.2 kb in the wild-type JA3453 strain was shifted to 1.5 kb in the ZH4 mutant strains (Fig. 3B). The ZH4 mutant strain was subsequently fermented to test for OZM production with the JA3453 wild-type strain as a positive control under identical conditions. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis showed a complete abolishment of OZM production in ZH4 (Fig. 3C), confirming the essential role the cloned locus plays in OZM biosynthesis.

FIG. 3.

Deletion of a portion of the ozm gene cluster by targeted gene replacement. (A) Schematic representation for the isolation of the ZH4 mutant strain via double-crossover homologous recombination and restriction maps of the S. albus JA3453 wild-type and ZH4 mutant strains upon PvuII digestion. B, BamHI; P, PvuII. (B) Southern analysis with a 1.5-kb PvuII fragment originating with pJTU1064 as a probe. (C) HPLC analysis of OZM production in wild-type (II) and ZH4 mutant (III) strains in comparison with the authentic OZM standard (I). OZM, ⧫.

Sequence analysis of the methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis locus and localization of the complete ozm biosynthetic gene cluster.

The 12.2-kb PvuII fragment containing the PCR-amplified HADH and ADH fragments was subcloned (pJTU1078). Sequencing of this region (12,249 bp) revealed 10 open reading frames (ORFS) [orf(-1) to (-3) and ozmA to -G] and an incomplete ORF, ozmH (Fig. 2B). The ozmBCDEFG genes are cotranscribed in the same orientation, presumably as an operon, since the numbers of the nucleotides between stop and start codons of the adjacent genes (i.e., 1 bp overlapping for ozmG and ozmF; 14 bp between ozmF and ozmE; 16 bp between ozmE and ozmD; 4 bp overlapping for ozmD and ozmC; 16 bp between ozmC and ozmB) are all too small to code any regulatory element for transcriptional initiation.

Five of the six genes within this apparent operon (with the exception of ozmC) are absolutely conserved among methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic loci known to date. For example, OzmG (287 amino acids) showed significant homology to members of the HADH family of enzymes, such as Asm13 (61% identity) (28), GdmK (61% identity) (20), FkbK (62% identity) (27), SorD (40% identity) (10, 29), and TtmE (64% identity) (9). Similarly, OzmF (221 amino acids) is a probable O-methyltransferase, OzmE is a probable ACP, OzmD is an ADH, and OzmB is an activating enzyme to channel a glycolytic pathway intermediate to methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis, all of which have homologs in known methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic loci (9, 10, 20, 27-29). Unique to the ozm locus is the presence of ozmC, whose deduced product showed significant sequence homology to DpsC (26% identity) from Streptomyces peucetius for doxorubicin biosynthesis. DpsC has been proposed to play a role in selecting the methylmalonyl-CoA starter unit for the Dps PKS (1). A similar function could be envisaged for OzmC to activate the glycolytic pathway intermediate as glyceryl-ACP to initiate methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis, a function that currently has been assigned solely to OzmB and its homologs (9, 10, 20, 27-29).

Upstream of ozmB is a divergently transcribed gene, ozmA, whose deduced product resembles a family of multidrug transporters, such as SgcB (28% identity) in C-1027 biosynthesis from Streptomyces globisporus (11), RemN (26% identity), involved in resistomycin biosynthesis, from Streptomyces resistomycificus (6), and EncT (27% identity) in enterocin biosynthesis from Streptomyces maritimus (19). Therefore, OzmA could act as an OZM-specific transporter to confer OZM resistance in S. albus JA3453. The three additional ORFs, orf(-3), orf(-2), and orf(-1), at the upstream location of the sequenced region encode proteins whose functions were not apparent in OZM biosynthesis and hence may represent one boundary of the ozm cluster (Fig. 2B).

The deduced product (397 amino acids) of the partial ORF, ozmH, downstream of the sequence region showed high sequence homology to AT-less PKSs that are known for hybrid peptide-polyketide biosynthesis, such as LnmI (59% identity), involved in leinamycin biosynthesis, from Streptomyces atroolivaceus (25), and PedF (52% identity), involved in pederin biosynthesis, from Paederus fuscipes (18). Colocalization of genes encoding hybrid NRPS-PKS with the methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis locus within the ozm biosynthetic gene cluster is consistent with the hybrid peptide-polyketide biosynthetic origin of OZM (2). Sequential chromosomal walking from the confirmed methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic locus led to the eventual localization of the complete ozm cluster within a 135-kb DNA region as represented by the overlapping cosmids of pJTU1059, pJTU1060, pJTU1061, pJTU1062, and pJTU1063, the downstream boundary of which has been preliminarily determined by shotgun sequencing (Fig. 2A).

ozmC inactivation and complementation.

To provide direct evidence that ozmC is required for OZM biosynthesis, it was inactivated by the PCR targeting and λ-RED-mediated gene replacement method (3) by means of an in-frame deletion strategy to eliminate any possible polar effect on the other genes within the ozmB to -G operon. The mutated plasmid pJTU1071 (ΔozmC), in which a 900-bp internal fragment of ozmC was deleted by the manipulations shown in Fig. 4A, was introduced into S. albus JA3453 by conjugation. Since pJTU1071 was constructed in the Streptomyces nonreplicative plasmid pOJ260, which contained the apramycin resistance gene (8), exconjugates were selected first for the Aprr (the first crossover event) and then for the Aprs (the second crossover event) phenotype to isolate the mutant strain ZH5 (ΔozmC) via the desired double-crossover homologous recombination event (Fig. 4A). This genotype was subsequently confirmed by PCR analysis, revealing that the 1.8-kb signal of ozmC in the wild-type JA3453 strain was shifted to 1.0 kb in ZH5, as would be expected from deleting the internal fragment from ozmC (Fig. 4B). Strain ZH5 completely lost its ability to produce OZM, as judged by HPLC analysis using the wild-type JA3453 as a positive control (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Characterization of ozmC by in-frame deletion and complementation. (A) Schematic representation for the isolation of the ZH5 mutant strain via double-crossover homologous recombination. (B) PCR analysis of wild-type and mutant strain genomic DNAs. Lane 1, wild type with ozmC-FP2 and ozmC-RP2; lane 2, ZH5 with ozmC-FP2 and ozmC-RP2; lane 3, 1-kb ladder. (C) HPLC analysis of OZM production in wild-type (I) and recombinant strains ZH5 (II) and ZH7 (III). OZM, ⧫.

To complement the ΔozmC mutation in ZH5, the ozmC (pJTU1079) expression vector was constructed in the φC31-based integrative plasmid pJTU1351, in which the expression of ozm is under the control of the constitutive ErmE* promoter, as follows. To prepare the ozmC expression construct, the ozmC gene was first amplified by PCR from pJTU1059 using primers 5′-C CAT ATG ACG ACG GCT GCC GGA GA-3′ (ozmC-FP3; the NdeI site is underlined) and 5′-T GAA TTC CGC CAC AGC GTG TTG TCC AG-3′ (ozmC-RP3; the EcoRI site is underlined). The resultant PCR product was recovered as a 1,045-bp NdeI-EcoRI fragment and ligated into the same sites of pBluescript SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to verify PCR fidelity by sequencing. The ozmC gene was then moved as a NdeI-EcoRI fragment from the pBluescript SK subclone and ligated into the same sites of a φC31-derived integrative vector, pJTU1351 (the ErmE* promoter was amplified from pWHM79 [22] as a 220-bp XbaI fragment to insert into the same site of pSET152 [8] to yield plasmid pJTU1351 using primers 5′-C TCT AGA ACG ACG GCT GCC GGA GA-3′ [ErmE*-FP; the XbaI site is underlined] and 5′-T TCT AGA CAT ATG CGC CAC AGC GTG TTG TCC AG-3′ [ErmE*-RP; the XbaI and NdeI site is underlined]), placing the expression of ozmC under the control of the ErmE* promoter, to afford pJTU1079. This plasmid was then introduced into the ZH5 mutant by conjugation, and Aprr exconjugants were selected (ZH7 for ZH5/pJTU1079). HPLC analysis confirmed that OZM production was partially restored in the ZH7 (∼40%) strain in comparison with the wild-type JA4353 strain as a control (the wild-type S. albus JA4353 strain typically produces OZM in an isolated yield of 10 to 15 mg/liter) (Fig. 4C). The identity of OZM was confirmed by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry analysis, yielding the characteristic (M+H)+ ion at m/e = 656.1, consistent with the molecular formula C36H49N3O9, and by 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance analysis, affording spectroscopic data identical to those reported in the literature (2, 13).

Summary.

The successful cloning and identification of the methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis locus from S. albus and confirmation of its essential role in OZM biosynthesis provide direct evidence supporting the methoxymalonate origin of the C3—C4 moiety of OZM. It also allowed us to map the entire OZM cluster by chromosomal walking from this locus. Preliminary sequence scanning of the 125-kb DNA downstream of the methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthetic locus has indicated that it includes at least 10 PKS modules and 3 NRPS modules for the assembly of the hybrid peptide-polyketide backbone of OZM. The PCR method reported should be of general use for the identification of other methoxymalonate-containing polyketide biosynthetic gene clusters as exemplified by the cloning of the tautomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces spiroverticillatus (9).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number DQ171941.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Analytical Instrumentation Center of the School of Pharmacy, UW—Madison, for support in obtaining MS and nuclear magnetic resonance data, John Innes Center, Norwich, United Kingdom, for providing the REDIRECT Technology kit, Werner F. Fleck, Hans Knoell Institute for Natural Product Research, Jena, Germany, for providing the S. albus JA3453 strain, and C. Richard Hutchinson for critical reading of the manuscript.

Work in the Shen lab was supported in part by the Graduate School and the School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin—Madison, a UWCCC Pilot Project program (CA014520), and a NCI National Cooperative Drug Discovery Group grant (CA113297). Work in the Deng lab was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology (2003CB114205), the National Science Foundation of China, the PhD Training Fund from the Ministry of Education, and the Shanghai Municipal Council of Science and Technology. B.S. is the recipient of an NIH Independent Scientist Award (AI51689).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bao, W., P. J. Sheldon, and C. R. Hutchinson. 1999. Purification and properties of the Streptomyces peucetius DpsC beta-ketoacyl:acyl carrier protein synthase III that specifies the propionate-starter unit for type II polyketide biosynthesis. Biochemistry 38:9752-9757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grafe, U., H. Kluge, and R. Thiericke. 1992. Biogenetic studies on oxazolomycin, a metabolite of Streptomyces albus (strain JA3453). Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1992:429-432. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henkel, T., and A. Zeeck. 1991. Inthomycins, new oxazole-trienes from Streptomyces sp. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1991:367-373. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda, Y., S. Kondo, H. Naganawa, S. Hattori, M. Hamada, and T. Takeuchi. 1991. New triene-β-lactone antibiotics, triedimycins A and B. J. Antibiot. 44:453-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakobi, K., and C. Hertweck. 2004. A gene cluster encoding resistomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces resistomycificus; exploring polyketide cyclization beyond linear and angucyclic patterns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:2298-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanzaki, H., K. I. Wada, T. Nitoda, and K. Kawazu. 1998. Novel bioactive oxazolomycin isomers produced by Streptomyces albus JA 3453. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:438-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 9.Li, W., J. Ju, H. Osada, and B. Shen. 2006. Utilization of the methoxymalonyl-acyl carrier protein biosynthesis locus for cloning the tautomycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces spiroverticillatus. J. Bacteriol. 188:4147-4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ligon, J. M., S. Hill, J. Beck, R. Zirkle, I. Molnar, J. Zawodny, S. Money, and T. Schupp. 2002. Characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the antifungal polyketide soraphen A from Sorangium cellulosum So ce26. Gene 285:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, W., S. D. Christenson, S. Standage, and B. Shen. 2002. Biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027. Science 297:1170-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manam, R. R., S. Teisan, D. J. White, B. Nicholson, J. Grodberg, S. T. C. Neuteboom, K. S. Lam, D. A. Mosca, G. K. Lloyd, and B. C. M. Potts. 2005. Lajollamycin, a nitro-tetraene spiro-β-lactone-γ-lactam antiobiotic from the marine Actinomycete Streptomyces nodosus. J. Nat. Prod. 68:240-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori, T., K. Takahashi, M. Kashiwabara, and D. Uemura. 1985. Structure of oxazolomycin, a novel β-lactone antibiotic. Tetrahedron Lett. 26:1073-1076. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura, M., H. Honma, M. Kamada, T. Ohno, S. Kunimoto, Y. Ikeda, S. Kondo, and T. Takeuchi. 1994. Inhibitory effect of curromycin A and B on human immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Antibiot. 47:616-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogura, M., H. Nakayama, K. Furihata, A. Shimazu, H. Seto, and N. Otake. 1985. Structure of a new antibiotic curromycin A produced by a genetically modified strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus, a polyether antibiotic producing organism. J. Antibiot. 38:669-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogura, M., H. Nakayama, K. Furihata, A. Shimazu, H. Seto, and N. Otake. 1985. Isolation and structural determination of a new antibiotic curromycin B. Agric. Biol. Chem. 49:1909-1910. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otani, T., K. I. Yoshida, H. Kubota, S. Kawai, S. Ito, H. Hori, T. Ishiyama, and T. Oki. 2000. Novel triene-β-lactone antibiotic, oxazolomycin derivative and its isomer, produced by Streptmyces sp. KSM-2690. J. Antibiot. 53:1397-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piel, J. 2002. A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14002-14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piel, J., C. Hertweck, P. R. Shipley, D. M. Hunt, M. S. Newman, and B. S. Moore. 2000. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the enterocin biosynthesis gene cluster from the marine isolate ′Streptomyces maritimus': evidence for the derailment of an aromatic polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 7:943-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rascher, A., Z. Hu, N. Viswanathan, A. Schirmer, R. Reid, W. C. Nierman, M. Lewis, and C. R. Hutchinson. 2003. Cloning and characterization of a gene cluster for geldanamycin production in Streptomyces hygroscopicus NRRL 3602. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Shen, B., and C. R. Hutchinson. 1996. Deciphering the mechanism for the assembly of aromatic polyketides by a bacterial polyketide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6600-6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiomi, K., N. Arai, M. Shinose, Y. Takahashi, H. Yoshida, J. Iwabuchi, Y. Tanaka, and S. Omura. 1995. New antibiotics phthoxazolins B, C and D produced by Streptomyces sp. KO-7888. J. Antibiot. 48:714-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi, K., M. Kawabata, and D. Uemura. 1985. Structure of neooxazolomycin, an antitumor antibiotic. Tetrahedron Lett. 26:1077-1078. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang, G. L., Y. Q. Cheng, and B. Shen. 2004. Leinamycin biosynthesis revealing unprecedented architectural complexity for a hybrid polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Chem. Biol. 11:33-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe, K., C. Khosla, R. M. Stroud, and S. C. Tsai. 2003. Crystal structure of an Acyl-ACP dehydrogenase from the FK520 polyketide biosynthetic pathway: insights into extender unit biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 334:435-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, K., L. Chung, W. P. Revill, L. Katz, and C. D. Reeves. 2000. The FK520 gene cluster of Streptomyces hygroscopicus var. ascomyceticus (ATCC 14891) contains genes for biosynthesis of unusual polyketide extender units. Gene 251:81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu, T. W., L. Bai, D. Clade, D. Hoffman, S. Toelzer, K. Q. Trinh, J. Xu, S. J. Moss, E. Leistner, and H. G. Fluss. 2002. The biosynthetic gene cluster of the maytansinoid antitumor agent ansamitocin from Actinosynnema pretiosum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7968-7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zirkle, R., J. M. Ligon, and I. Molnar. 2004. Heterologous production of the antifungal polyketide antibiotic soraphen A of Sorangium cellulosum So ce26 in Streptomyces lividans. Microbiology 150:2761-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]