Abstract

Bacteriophages of the Siphoviridae family utilize a long noncontractile tail to recognize, adsorb to, and inject DNA into their bacterial host. The tail anatomy of the archetypal Siphoviridae λ has been well studied, in contrast to phages infecting gram-positive bacteria. This report outlines a detailed anatomical description of a typical member of the Siphoviridae infecting a gram-positive bacterium. The tail superstructure of the lactococcal phage Tuc2009 was investigated using N-terminal protein sequencing, Western blotting, and immunogold transmission electron microscopy, allowing a tangible path to be followed from gene sequence through encoded protein to specific architectural structures on the Tuc2009 virion. This phage displays a striking parity with λ with respect to tail structure, which reenforced a model proposed for Tuc2009 tail architecture. Furthermore, comparisons with λ and other lactococcal phages allowed the specification of a number of genetic submodules likely to encode specific tail structures.

The overwhelming majority of identified bacteriophages possess tails and belong to the order Caudovirales (6). The bacteriophage tail represents a supramolecular organelle with which the phage adsorbs to the host cell and injects its DNA into the cytoplasm (18). Members of the Caudovirales can be further subdivided on the basis of tail morphology to belong to the Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, or Podoviridae. Myoviridae have long contractile tails, while Siphoviridae and Podoviridae possess long and short noncontractile tails, respectively. The majority of phages classified to date belong to the Siphoviridae and, thus, this group is assumed to represent the most abundant phage morphotype in the environment (1, 6).

The molecular process of tail assembly has been extensively studied for a small number of phages infecting gram-negative bacteria (18, 22), in contrast to phages infecting gram-positive hosts, where this phenomenon is largely neglected. In recent years, however, a small number of studies on phages infecting gram-positive lactic acid bacteria have provided some insights into this process. The most comprehensive early reports on tail assembly focused on the lactococcal phages c2 and TP901-1 (16, 24). In these reports, N-terminal sequencing of phage structural proteins, along with immunogold electron microscopy, was used to identify and locate the major tail protein (MTP) and tail adsorption protein on the c2 virion, while the neck passage structure (NPS), MTP, and a single baseplate protein (BPP) were identified for TP901-1.

Despite these early studies, the majority of subsequent information in this area is largely speculative and is based primarily on sequence comparisons with the burgeoning number of completed phage sequences in the databases. However, several studies are noteworthy. Through the generation and analysis of two mutant phages, which were deficient in putative structural genes, Pedersen et al. (26) identified the tape-measure protein (TMP) and a baseplate protein of TP901-1. Duplessis and Moineau (12) were the first to identify Streptococcus thermophilus tail genes as the determinants of host specificity through the generation of chimeric phages with altered host range; following this lead, Stuer-Lauridsen et al. (30) and Dupont et al. (13) have identified the antireceptors of a number of c2 and 936-type lactococcal phages, respectively. Kenny et al. (19) have identified the tail-associated lysin of phage Tuc2009 (Tal2009), which is located at the tip of the phage tail and is capable of degrading lactococcal cell walls, presumably to allow the Tuc2009 DNA injection machinery access to host cell membrane.

Vegge et al. (32) have recently characterized the distal tail structure of the temperate lactococcal phage TP901-1 by examining the effects of mutations on tail assembly and morphology. The data presented, in conjunction with that of the earlier report by Pedersen et al. (26), enabled the authors to present a model for TP901-1 tail morphogenesis in which three tail proteins form an initiator complex (IC) that acts as a hub around which the other tail components are assembled. In a further study, a chimeric TP901-1 phage that displays the host range of the closely related Tuc2009 phage, thereby implicating the lower baseplate protein (BppL) as pivotal for host recognition, was constructed (33).

This report outlines the most detailed anatomical description of a phage infecting a gram-positive host to date. Together with the previously published molecular and transcriptional analysis of Tuc2009 (29), the data presented here allow direct and definite links to be made between individual genes on the phage genome through their encoded proteins to specific architectural structures on the Tuc2009 virion. One only has to skim the surface of the literature regarding phages, such as λ or T4, that were studied prior to the genomic age to appreciate how much the balance has swung from detailed anatomical and physiological studies to the current situation. The data presented in this article complete a trilogy focusing on the tail structures of Tuc2009 and the closely related TP901-1 (32, 33) and, in the context of a single body of work, represent a significant step forward in our understanding of lactococcal bacteriophage anatomy. Furthermore, the experimental data presented in conjunction with the existing genome sequences for the Sfi11 and r1t-type lactococcal bacteriophages have allowed the subdivision of the their tail structural gene modules on the basis of the architectural roles fulfilled by the encoded products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, bacteriophages, and growth media.

Bacteriophages, bacterial strains, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Lactococcus lactis strains were grown at 30°C in M17 medium (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, England) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17) or glucose streptococcal broth medium, a modified version of lactose streptococcal broth that contains glucose instead of lactose (2). Escherichia coli strains were cultivated with agitation at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth or agar (1.4%) (28). E. coli M15 cells containing pQE60 or derivatives thereof were grown in the presence of 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1 and 25 μg of kanamycin ml−1, and Tuc2009 was propagated on UC509.9 and purified as described previously (25). The wild-type and the 48− mutant TP901-1 phage were induced from the respective lysogenic L. lactis 901-1 and CSV61-1 strains and purified as described previously (32).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study

| Bacterial strain, plasmid, or phage | Relevant feature | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ||

| UC509.9 | Prophage-cured host for Tuc2009 | 9 |

| 901-1 | Lysogenic for phage TP901-1 | 4 |

| CSV61-1 | 901-1 lysogenic for TP901-1 bppU mutant | 32 |

| E. coli M15 | Host for pQE60 plasmids; contains pREP4, Kanr | QIAGEN |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| Tuc2009 | Temperate phage of L. lactis subsp. cremoris UC509 | 9 |

| TP901-1 | Temperate phage of L. lactis subsp. cremoris 901-1 | 4 |

| 48− | TP901-1 derivative with amber mutation in bppU gene | 32 |

| Plasmids | ||

| PQE60 | E. coli expression vector, Ampr | QIAGEN |

| PQ452009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf45 | This study |

| PQ462009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf46 | This study |

| PQ472009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf47 | This study |

| PQ48C2009 | PQE60 + 1,914 bp (3′ end) of Tuc2009 orf48 | This study |

| PQ492009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf49 | This study |

| PQ50N2009 | PQE60 + 540 bp (5′ end) of Tuc2009 orf50 (tal2009) | This study |

| PQ512009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf51 | This study |

| PQ522009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf52 | This study |

| PQ532009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf53 | This study |

| PQ542009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf54 | This study |

| PQ552009 | PQE60 + Tuc2009 orf55 | This study |

Electron microscopy and immunological detection.

Purified phage preparations were dialyzed for 10 to 15 min against SM buffer (100 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM magnesium sulfate, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.01% [wt/vol] gelatin) for negative staining or TGB buffer (200 mM Tris, 500 mM glycine, 2% [vol/vol] butanol [pH 7.5]) for immunogold labeling. For negative staining, a carbon film was floated from a mica sheet into a suspension of dialyzed phages and incubated for 10 min. The film was subsequently rinsed in deionized water and was finally stained with 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate (Agar Scientific, Stansted, United Kingdom) for 30 s. The carbon film was picked up with 400-mesh copper grids (Agar Scientific) and examined using a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai 10; FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV. Micrographs were taken with a MegaView II charge-coupled-device camera (SIS, Münster, Germany). For colloidal gold immunolabeling, dialyzed phages were incubated overnight at room temperature with primary antibody solutions, which were diluted 1:300 in TGB buffer. A carbon film was floated from a mica sheet into the suspension and incubated for 30 min. Alternatively, phages were first adsorbed to a carbon film for 30 min and then incubated overnight in primary antibody solutions. The carbon films were subsequently washed in TGB buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G 5-nm gold conjugate solution (BBI, Cardiff, United Kingdom) diluted 1:40 (wt/wt) with TGB buffer. After fixation for 20 min at room temperature in 0.25% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline buffer, negative staining was performed as described before, except that 400-mesh nickel grids (Agar Scientific) were used instead of copper grids.

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

PCR amplifications of Tuc2009 open reading frames (ORFs) (or sections thereof) were performed using an EXPAND long-template PCR system (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions with a GeneAmp PCR system 2400 thermal cycler (PerkinElmer). The genomic coordinates of the amplified regions are listed in Table 2. Restriction enzymes, shrimp alkaline phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase were supplied by Roche (Mannheim, Germany) and employed as recommended by the manufacturer. Oligonucleotides were manufactured by MWG (Ebersberg, Germany). Plasmid purifications from E. coli were performed using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (QIAGEN, West Sussex, United Kingdom). Sequence analysis was performed by MWG (Ebersberg, Germany).

TABLE 2.

Genome coordinates of the amplified regions

| Tuc2009 orf | Genome coordinates | Protein product |

|---|---|---|

| orf45 | 23727-24224 | MTP2009 |

| orf46 | 24340-24657 | gpG2009 |

| orf47 | 24714-25034 | gpT2009 |

| orf48 | 25049-28126 (26217-28123)a | TMP2009 |

| orf49 | 28136-28897 | Dit2009 |

| orf50 | 28897-31617 (28897-29437)a | Tal2009 |

| orf51 | 31630-32598 | BppU2009 |

| orf52 | 32600-33460 | BppA2009 |

| orf53 | 33479-34000 | BppL2009 |

| orf54 | 34013-34237 | None assigned |

| orf55 | 34250-36280 | NPS2009 |

Parentheses indicate sections of the gene that were PCR amplified and cloned in pQE60.

Plasmid construction.

Specific PCR-generated DNA fragments representing each of the eight complete ORFs from the Tuc2009 tail module were produced along with the 3′ and 5′ fragments of ORFs tmp2009 and tal2009, respectively (see Table 2 for the genomic coordinates). NcoI and BglII sites were incorporated into the relevant synthetic oligonucleotides to facilitate cloning in the E. coli expression vector pQE60 (Table 1). The stop codon defining the 3′ end of a particular gene was omitted from complementary oligonucleotides, allowing a translational fusion of each of the cloned genes with the six-His tag encoded by pQE60. Electrotransformation of plasmid DNA into E. coli was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (28). The integrity of all constructs was checked by restriction profiling and DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification.

The overexpression of target proteins was achieved using the E. coli expression plasmid pQE60 essentially as recommended by QIAGEN (West Sussex, United Kingdom). Induction was accomplished over a 4-h period and was initiated when the culture had reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.35 to 0.4 using isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma) at a final concentration of 1 mM. Cultures (250 ml) of E. coli were used to express proteins for polyclonal antibody production. Cells were harvested in a Beckman J2-21 centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, California) at 4,000 rpm for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer and disrupted in an alcohol ice bath using ultrasonication (Soniprep 150) with 30-s bursts of an amplitude of 10 μm followed by 15-s breaks. This sonication was continued for 10 min. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20 min in an Eppendorf bench-top centrifuge, and the overexpressed proteins were purified by immobilized metal-affinity chromatography. Briefly, this involved passing the lysates through columns containing 4 ml of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid matrix (QIAGEN) which had been pre-equilibrated with 10 ml of the lysis buffer, followed by two 10-ml washes with wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 1 M NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The proteins were then eluted in approximately 1-ml aliquots using 10 ml of the elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 1 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). Minor adjustments to the wash buffer pH and the Triton X-100 concentration were made for the optimal purification of individual proteins. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., California) in conjunction with a bovine serum albumin standard curve.

SDS-PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described by Laemmli (21) using a 4% stacking gel and a 12% or 15% separating gel, as appropriate. Protein sizes were compared to a prestained protein marker (New England BioLabs, Massachusetts).

N-terminal amino acid sequences of structural phage proteins.

Tuc2009 structural proteins were separated by boiling concentrated CsCl-purified phage particles in sample buffer for 20 min prior to SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were either visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue or transferred to ProBlott membranes (Applied Biosystems). The blots were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and protein bands were excised and their N-terminal amino acid sequences determined with the aid of an Applied Biosystems 477A protein sequencer.

Polyclonal antibody preparation.

Polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbits by Harlan Sera-Lab (Leicestershire, England) using its standard protocol. Initial immunizations of individual proteins were complemented with Freund's complete adjuvant with five subsequent booster injections of protein. Protein concentrations in initial immunization and booster injections were in the 150- to 200-μg/ml range. The final serum samples were acquired 11 weeks after the initial immunizations.

Western blot analysis following Tuc2009 infection.

An early log-phase culture of UC509.9 (OD600, 0.3) was infected with Tuc2009 to give a multiplicity of infection of approximately 1, and the OD600 was monitored throughout the infection. Aliquots were removed from the culture at 10-min intervals commencing 10 min prior to infection and proceeding until cell lysis occurred during the 60- to 70-min monitoring period. Aliquots were frozen immediately after sampling by being stirred in a dry ice-alcohol bath. Frozen samples were subsequently thawed on ice, and cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were washed, resuspended in ice-cold 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7), and lysed by disruption in a Mini-BeadBeater-8 (BioSpec Products) for 10 min at 4°C. Whole cells, cellular debris, and insoluble proteins were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20 min in an Eppendorf bench-top centrifuge, and the protein concentration of the supernatants was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Protein samples were adjusted prior to SDS-PAGE such that all lanes contained equivalent total protein concentrations.

Western blotting and immunological detection.

Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) using a 0.1 M CAPS [3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid; pH 11], 10% methanol transfer buffer (Mini-PROTEAN II; Bio-Rad Laboratories). Detection using polyclonal antibodies involved two 10-min washes of the membranes in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl) followed by a 10-min wash in TBS-Tween-Triton X-100 (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.2% Triton X-100). Membranes were then incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer (TBS, 5% skimmed milk powder, 0.1% Tween 20). The three washes were repeated, after which the primary antibody was allowed to interact with its antigen by incubation of the membrane in blocking buffer with an appropriate dilution (generally 1:1,000) of the polyclonal rabbit serum. Following the repetition of the three wash steps, the secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit donkey immunoglobulin G (Amersham Biosciences), was incubated with the membrane in the same manner as described for the primary antibody. Four further 10-min washes in TBS-Tween-Triton X-100 were performed, and the antigen-antibody complexes were detected using an ECL Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein sizes were determined using a biotinylated protein ladder detection pack (Cell Signaling Technologies).

RESULTS

Identification of minor structural proteins.

The tail gene modules of Tuc2009 and TP901-1 are highly homologous, both in gene order and amino acid identity between the individual proteins (Fig. 1). Architectural functions have been assigned to the Tuc2009 tail proteins on the basis of the experimental data presented below and their similarity to structural proteins of TP901-1 (32). For clarity, in the first instance, proteins will be referred to by their functional or architectural designation, and readers should refer to the subsequent sections for data and reasoning supporting such designations. Comparisons between structural proteins of Tuc2009 and TP901-1 are made in the text and, consequently, protein designations are given a 2009 subscript when they refer to Tuc2009 and a TP901 subscript when they refer to TP901-1.

FIG. 1.

Comparative analysis of the structural tail modules of the three Sfi11-type phages, ul36, Tuc2009, and TP901-1, and the two r1t-type phages, LC3 and r1t. Proteins with predicted or proven functions are indicated by colored arrows. Amino acid identity between proteins is indicated by shaded regions. A schematic representation of genes encoding the structural tail proteins of λ is included for comparison.

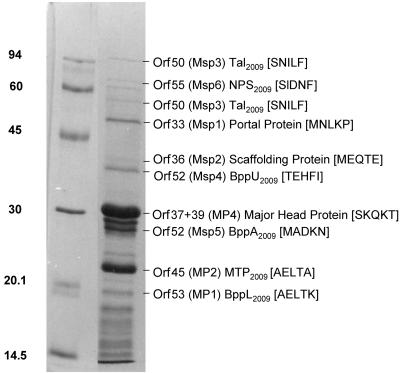

The N-terminal sequence of four major structural proteins of Tuc2009 have been determined previously. For two of these (MP1 and MP2), the corresponding genes were identified. MP1, encoded by orf532009, was assigned as the baseplate protein (here reassigned as the lower baseplate protein [BppL2009]), and MP2, which is encoded by orf452009, was assigned as the major tail protein (MTP2009) (2). It was subsequently demonstrated that MP3, which is encoded by orf62009, was erroneously identified as a structural protein, as it does not, in fact, form part of the Tuc2009 virion (S. Mc Grath, J. G. Kenny, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen, unpublished data). The other previously determined structural protein, MP4, is encoded by orf372009 and orf392009 and represents the major head protein. Synthesis of this protein requires the excision of a group I intron that also encompasses orf382009 (29) and results in a mRNA that represents a fusion of orf372009 and orf392009, which is then translated into the major head protein. Here, we present a more in-depth analysis that includes a number of minor structural proteins that have not been identified previously (Fig. 2). In order to determine the identity of the genes encoding these minor structural proteins, N-terminal analysis of several proteins was performed as indicated in Materials and Methods and compared to the deduced sequence of the identified orf genes on the Tuc2009 genome (29).

FIG. 2.

N-terminal sequence analysis of Tuc2009 structural proteins. Concentrated Tuc2009 phage particles were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the N-terminal sequence of the resulting protein bands was determined. The major structural proteins, MP1, MP2, and MP4, have been reported previously, and their N-terminal sequence is included for consistency. Orf designations and proven or predicted functions are listed opposite the corresponding protein band on the SDS-PAGE gel, and the first five N-terminal amino acids determined are indicated in parentheses.

Two protein bands were found to possess an identical N-terminal sequence corresponding to the translated gene product of orf502009 (Msp3) (Fig. 2). The calculated size of the larger protein corresponds to the predicted size of the translation product of orf502009 (101.1 kDa), with the smaller protein exhibiting an approximate size of 55 kDa. Kenny et al. (19) have demonstrated that Tal2009, the protein encoded by orf502009, undergoes a self-mediated posttranslational processing event at a specific glycine-rich region during phage maturation in vivo, which would account for both of these bands. The calculated molecular mass for the gene product of orf362009 (Msp2) is 24.5 kDa. However, its relative position following SDS-PAGE corresponds to a molecular mass of 40 kDa, which may indicate that this protein exists in a complex that is covalently associated with another protein(s). The proteins corresponding to the gene product of orf332009 (portal protein), orf512009 (upper baseplate [BppU2009]) orf522009 (baseplate associated [BppA2009]), and orf552009 (neck passage structure [NPS2009]) (Msp1, Msp4, Msp5, and Msp6, respectively) exhibit mobilities that would be expected from their respective calculated molecular sizes (29).

Phage morphology.

It has been reported previously that the Tuc2009 virion structure, consisting of a small isometric head, a long noncontractile tail, and a baseplate, is typical of the Siphoviridae (2). A more detailed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis reveals a greater degree of anatomical complexity (Fig. 3A). A collar structure can be observed at the position where the head and tail meet (Fig. 3A, arrow i) and, in some cases, two whisker-like appendages protruding from the top of the collar or bottom of the head are visible (Fig. 3A, arrows v). The baseplate (Fig. 3A, arrow iii) appears to consist of a single disk with several irregular teardrop-like appurtenances attached to it, reminiscent of a petticoat (Fig. 3A, arrow iv). However, in some instances, this petticoat structure is not visible, revealing the presence of a conical structure under the baseplate (Fig. 3A, arrow vi) from which a fiber protrudes (Fig. 3A, arrow vii). The mean measurements taken from multiple individual Tuc2009 virions display striking similarities to those reported for λ with respect to head diameter, tail length, and tail diameter (Fig. 3A and B) (18). Furthermore, the numbers of individual disks visible in the tail shaft (Fig. 3A, arrow ii) are comparable for these two phages, with 34 ± 1 (n = 18) present for Tuc2009 compared to 32 for λ (18).

FIG. 3.

TEM analysis of Tuc2009 and model of phage virion showing anatomical features and dimensions. (A) Anatomical features and dimensions of the Tuc2009 virion. (i) Collar and whiskers (NPS2009), (ii) tail shaft (MTP2009), (iii) upper baseplate (BppU2009), (iv) petticoat structure (BppL2009), (v) whiskers (NPS2009), (vi) conical structure (Dit2009), (vii) tail fiber (Tal2009). (B) Detail of proposed protein architecture of tail adsorption apparatus.

Western blot analysis.

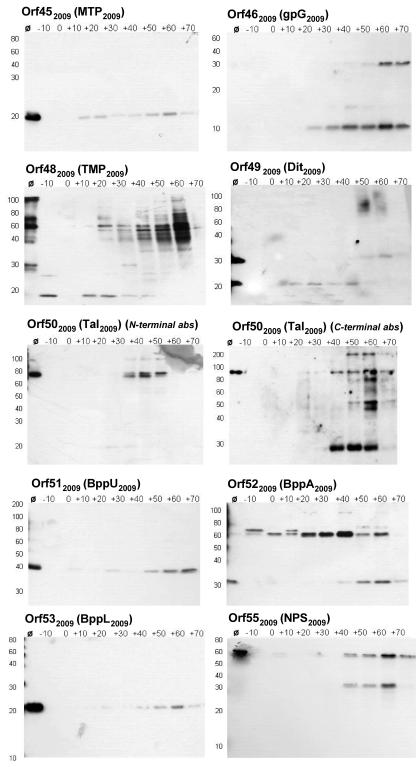

Western blot analysis was used to monitor the in vivo production of Tuc2009 tail proteins during lytic propagation of the phage. The data generated using antibodies directed against Orf452009 (MTP2009), Orf512009 (BppU2009), Orf522009 (BppA2009), Orf532009 (BppL2009), and Orf552009 (NPS2009) antibodies demonstrate that all of these proteins are present as full-length polypeptides in the Tuc2009 virion (Fig. 4, lanes Ø).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of Tuc2009 tail proteins. Intracellular protein samples from Tuc2009-infected UC509.9 were probed with polyclonal antibodies specific for individual Tuc2009 tail proteins. Samples were prepared as outlined in Materials and Methods. Polyclonal antibodies used are indicated in the top left corner of each panel, and protein sizes (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left side of each panel. Ø, CsCl-concentrated Tuc2009 phage particles. −10 to +70, time (in minutes) that a sample was taken, relative to the addition of phage at time zero.

The protein products of orf462009 (gpG2009) and orf46-472009 (gpGT2009) most likely fulfill roles analogous to that of the tail assembly proteins gpG and gpGT of bacteriophage λ (23) and are therefore not expected to be incorporated into the mature Tuc2009 virion, as was confirmed by the absence of a gpG2009-specific band on the Tuc2009 virion (Fig. 4, lanes Ø). Two anti-46 antibody-specific bands are present in Fig. 4. The smaller band, corresponding to a molecular mass of approximately 10 kDa, is assumed to represent gpG2009. The larger band, of about 30 kDa, most likely represents a translational fusion of orf462009 and orf472009, resulting in gpGT2009 (see Discussion). Antibodies directed against the protein product of orf472009 did not react with any protein bands under the conditions used. Control experiments performed using purified recombinant Orf472009 protein and the anti-472009 antibody demonstrated no immunogenic reaction between this protein and antibodies under standard Western blot conditions. This result indicates that the antibody is unsuitable for detecting the predicted gpGT2009 fusion polypeptide and explains the absence of a commensurately sized band in the Western blot analyses.

The tail tape measure protein (TMP2009) is encoded by orf482009 of Tuc2009. It has been demonstrated that the C-terminal portion of the tape measure protein (gpH) of λ is proteolytically cleaved prior to the joining of the head and tail structures (14, 31). This also appears to be the case for TMP2009, for which a major band of approximately 60 kDa is evident upon probing with anti-482009C antibody. This observation is in good agreement with that reported for TMPTP901-1 by Petersen et al. (26) However, a band corresponding to the expected full-length polypeptide of 110 kDa is also apparent, indicating that both the processed and the unprocessed forms of TMP2009 may be present in the virion. Two bands, of approximately 20 and 30 kDa, are visible when the virion lane is probed with anti-492009 antibody. The protein product of orf492009 (Dit2009) has a predicted molecular mass of 29.12 kDa, and this led us to speculate that the 30-kDa band visible on the Western blot represents the full-length Dit2009 polypeptide and that the smaller, 20-kDa band is either a cleavage product of it or is due to cross-reaction. Control experiments using purified Dit2009 and MTP2009 protein subsequently revealed that the anti-492009 antibody does, in fact, cross-react with MTP2009, resulting in the secondary 20-kDa band (data not shown). It has recently been reported that Tal2009, which is encoded by orf502009, undergoes self-mediated posttranslational processing at a glycine-rich region contained within the polypeptide (19). The N-terminal sequence data presented above (Fig. 2) confirm this observation by identifying two protein bands with differing molecular masses but with an N-terminal amino acid sequence identical to that predicted from the orf502009 DNA sequence. The antibodies directed against the N-terminal portion of Tal2009 react with two bands in Fig. 4. The faint upper band at approximately 100 kDa represents the full-length polypeptide, and the more intense band at approximately 70 kDa represents the N-terminal fraction of the processed protein. When the anti-502009 C antibody was used in the same analysis, a single band representing the full-length polypeptide is evident in the virion lane, and the secondary, smaller, processed 30-kDa band is also visible in the lanes containing samples from Tuc2009-infected cells.

The protein products of orf522009 (BppA2009) and orf552009 (NPS2009) share two conserved stretches of amino acids (for BppA2009, amino acids 10 to 31 and 185 to 199; for NPS2009, amino acids 419 to 440 and 568 to 582, respectively) (29), which is likely to be the cause of cross-reaction of these antibodies with both proteins, resulting in the secondary bands present in Fig. 4. The bands visible at approximately 30 kDa in the BppA2009 panel are due to hybridization of the anti-522009 antibody with BppA2009, whereas the bands present at 60 kDa are most likely due to the cross-reaction of this polyclonal antibody with NPS2009. Conversely, in the NPS2009 panel of Fig. 4, the larger, approximately 60-kDa bands are specific to the anti-552009 antibody, and the smaller bands are assumed to be the result of cross-reaction with BppA2009.

Immunogold transmission electron microscopy.

In order to determine the precise location of the individual protein components constituting the Tuc2009 phage tail, a series of immunogold electron microscopy analyses was performed. As indicated in Materials and Methods, phage samples were first incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for individual proteins and, following several washes, these preparations were incubated with gold-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies. The electron-dense gold-labeled antibodies appear as black spots when viewed with a transmission electron microscope, thus marking the position of the protein on the phage virion. Incubation of phage particles with the gold-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies in the absence of prior incubation with specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies resulted in a random scattering of black spots on the grids when viewed under the microscope (data not shown). This indicates that specific labeling of phage virion structural components occurs only in the presence of the primary antibody.

Antibodies directed at the protein encoded by orf452009, which on the basis of amino acid similarity was previously indicated as encoding the major tail protein, coat the entire length of the tail shaft, confirming that this protein is abundantly present in this structure and thus warrants the assignation MTP2009 (Fig. 5A). Antibodies specific for the product of orf492009 (95% amino acid similarity to the TP901-1 distal tail protein, DitTP901-1) bound to the base of the Tuc2009 tail (Fig. 5B). Immunogold EM localization of the protein product of orf502009, Tal2009, using an antibody directed against a C-terminal portion of it has been reported previously (19), and data from the present study support the finding that Tal2009 is located at the Tuc2009 tail tip (Fig. 5 C). The protein product of orf512009 (80% amino acid similarity to the TP901-1 upper baseplate protein, BppUTP901-1) was localized to the baseplate (Fig. 5D), while antibodies specific for the orf532009-derived protein, designated the lower baseplate protein (BppL2009), also bound to a baseplate-associated structure (Fig. 5E). Antibodies specific for the Tuc2009 neck passage structure, encoded by orf552009 (NPS2009), were labeled at the top of the tail just beneath the head (Fig. 5F). Similar experiments performed with the antibodies outlined above, with the exception of anti-orf532009 antibody, on wild-type TP901-1 localized the homologous proteins to the corresponding positions on the TP901-1 virion (32) (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunogold TEM analysis of Tuc2009. Specific proteins were located on the Tuc2009 and TP901-1 (48− mutant) virions as described in Materials and Methods. Panels A to F, Tuc2009. Panel G, TP901-1. (A) Anti-45abs (MTP2009), (B) anti-49abs (Dit2009), (C) anti-50Cabs (Tal2009), (D) anti-51abs (BppU2009), (E) anti-53abs (BppL2009), (F) anti-55abs (NPS), (G) anti-48abs (TMP2009).

No specific labeling could be detected for wild-type Tuc2009 or TP901-1 when antibodies against gpG2009, gpGT2009, TMP2009, Tal2009 (N terminus), or BppA2009 were tested. The proteins encoded by orf462009 (gpG2009) and orf462009-472009 (gpGT2009) of Tuc2009 are expected to fulfill roles analogous to those of the tail assembly proteins gpG and gpGT of bacteriophage λ which, while essential for tail maturation, are not included as structural tail elements (see below). The tape measure protein (TMP2009) is encoded by orf482009. TMPTP901-1 has been shown to be essential for tail formation, and it has been proposed that it, together with DitTP901-1 and TalTP901-1, forms an initiator complex around which the other tail components are assembled (32). Therefore, it is likely that other tail structures, such as the baseplate, would block access to anti-TMP2009 antibodies, thus preventing localization of this protein using this technique. Vegge et al. (32) have constructed a mutant derivative of TP901-1, 48−, that lacks the double baseplate structure characteristic of the wild-type phage, and it was hypothesized that this mutant phage may be more suitable for localizing TMPTP901-1 on the virion. This was found to be the case with antibodies directed against the C-terminal portion of TMP2009, which specifically recognized a structure at the base of the TP901-1 48− tail (Fig. 5G). Furthermore, it was observed that antibodies specific for Dit2009 and the C-terminal portion of Tal2009 labeled this 48− mutant TP901-1 derivative with a higher affinity than either wild-type TP901-1 or Tuc2009 (data not shown). These observations indicate that the baseplates most likely hinder these antibodies from accessing their antigen(s). Immunogold labeling with the antibody generated against the N-terminal portion of Tal2009 was unsuccessful. It has been shown here and previously that antibodies against the C terminus of this protein adhere to the tip of the phage tail (19). This leads us to speculate that, in a manner similar to that of the λ J tail fiber protein (34), the N terminus of Tal2009 is involved in interaction with other tail proteins, most likely TMP2009 and/or Dit2009. It is therefore possible that these proteins prevent anti-502009 N antibodies from accessing their antigen(s). Both TMPTP901-1 and DitTP901-1, along with TalTP901-1, are essential for TP901-1 tail assembly, and mutations in any of the three encoding genes render those phages tailless (32). Therefore, it is not possible to test a mutant TP901-1 phage with anti-50N in a manner similar to that for antibodies specific for TMPTP901-1 and DitTP901-1. Orf522009 is specific to Tuc2009, but its genomic location, between the Tuc2009 homologs of the TP901-1 upper (BppUTP901-1) and lower (BppLTP901-1) baseplates, suggests that this protein may also be inaccessible to antibodies specific for it. On this basis, the protein product of orf522009 has been presumptively denoted as a baseplate-associated protein (BppA2009).

DISCUSSION

The similarity of the organization of structural genes between lactococcal and lambdoid phages has been highlighted previously (5, 8, 11) and has prompted proposals to restructure phage taxonomy in light of the ever-expanding pool of completed phage genome sequences. However, the mosaic nature of bacteriophage genomes represents a significant hurdle to the development of an ordered set of taxonomic principles. In addressing this problem, Proux et al. (27) have proposed a classification system based on the comparative genomics of a single structural gene module (head or tail genes). Ironically, when this ideology was applied to the tail modules of lactococcal phages, six distinct gene organizations in the Siphoviridae were identified. Under this system, members of the P335 species of lactococcal phages according to Jarvis et al. (15) are classified into three groups. The lytic phage ul36 and the temperate phages TP901-1 and Tuc2009 are placed in the Sfi11 group; two other temperate phages, LC3 and r1t, are placed in the r1t group. The remaining temperate P335 phage and bIL285, bIL286, bIL309, BK5-T, and 4268 are all members of the proposed Sfi21 group (27) and display a structural gene module less similar to λ than to the Sfi11 or r1t members and therefore are not considered here.

In Fig. 1, the tail gene modules of Sfi11 and r1t lactococcal phages are compared to that of λ. The λ genes are subgrouped according to the distinct phases of tail morphogenesis in which they are involved (17). Genes v to t are responsible for tail tube formation, genes h to j code for proteins involved in initiator complex formation, and stf and tfa encode the nonessential long tail fibers (genes z and u precede the λ tail tube genes and direct tail elongation termination and maturation but are not considered here). An inverse relationship exists between the arrangement of genes in the λ tail module and the temporal order of protein interactions during tail morphogenesis, which appears to be conserved for the members of the sfi11 and r1t groups considered here. The data presented in this article, in conjunction with the recent report by Vegge et al. (32), have enabled the identification of λ-like tail submodules for the Sfi11-type lactococcal phages and, to a lesser extent, the r1t-type phages considered, which sheds new light on their possible physiological roles (Fig. 1).

The formation of the IC in λ involves the interaction of six proteins, including the tape measure protein (gpH) and the tail fiber protein (gpJ). The formation of this protein complex provides the impetus for tail assembly and, consequently, will be considered first. It has been proposed previously that the proteins TMPTP901-1, DitTP901-1, and TalTP901-1 constitute the TP901-1 IC (ICTP901-1) (32). The immunogold TEM data presented here support this idea, as these three proteins have been demonstrated to occupy similar anatomical positions on the Tuc2009 and TP901-1 virions (Fig. 5B, C, and G and data not shown). This finding suggests that these proteins may interact to form an IC substructure around which the phage tail is built, in a manner similar to that of λ (18). Furthermore, the antibody directed against the N-terminal portion of Tal2009 failed to specifically label any structure on the Tuc2009 or TP901-1 virions, indicating that, similar to the λ gpJ protein (34), the N terminus of Tal2009 may be involved in interacting with the other components of the IC2009 and is thus inaccessible to the antibodies. Immunogold TEM analysis has confirmed the proposed conical structure constituted by DitTP901-1 at the distal end of the TP901-1 tail tube (32) and indicated an identical role for Dit2009 (Fig. 5B and 3B). The role of Dit2009 is apparently solely architectural in contrast to the dual roles of IC2009 formation/host cell wall degradation and IC2009 formation/Tuc2009 tail tube length determination fulfilled by Tal2009 and TMP2009, respectively. Data presented here and elsewhere show that the Tal2009 forms a fiber structure that is located at the tip of the phage tail (Fig. 5C) (19), with TMP2009 expected to protrude from IC2009 into the tail tube in a manner similar to that proposed for TP901-1 (32). The conical structure formed by Dit2009 is likely to facilitate the interaction of all three IC components, while of the 10 Tuc2009 tail proteins analyzed in this study, Dit2009 appears to be the least abundantly produced, being detectable by Western blotting for only a 10-min period late in the infection (Fig. 4). Control experiments performed with purified tail proteins and their cognate polyclonal antibodies indicated comparable immunogenic reactions for all antibody-protein pairs (data not shown). These observations lead us to propose that Dit2009 orchestrates IC2009 formation, whereby the complex cannot form until sufficient amounts of Dit2009 are present in the cell.

The IC genes are well conserved in the Sfi11 lactococcal phage, whereas this is not found to be the case for r1t and LC3 (Fig. 1). However, parallels that can be drawn between the Sfi11 members and r1t and LC3 have allowed us to propose a putative IC submodule for these phages also. Similar to λ, a TMP-encoding gene is situated immediately downstream of the tail tube submodule for the five lactococcal phages considered in Fig. 1. In addition, the lactococcal phage tmp genes are immediately succeeded by dit and tal for the three Sfi11 phages and two cryptic genes for both r1t and LC3, with the next immediate downstream gene for all five phages encoding a baseplate-associated protein (Fig. 1). On this basis, we propose that the genes situated between the λ-t analogue and the baseplate-encoding genes represent the IC submodule for all five lactococcal phages. Following the formation of ICλ, the major tail protein (gpV) polymerizes onto it to form the tail tube (18). The gpV protein, with a molecular mass of 33 kDa, is approximately double the mass of MTP2009 (16.8 kDa) (18, 29). However, a high degree of anatomical parity exists between the λ and Tuc2009 tail tube structures. The λ tail tube is 135 nm in length, comprising 32 disks of gpV hexamers, each consisting of an annular ring (9 nm in diameter) with a central hole (3 nm in diameter) and six outer knobs (18). The TEM data for Tuc2009 reveal a highly similar tail tube structure, measuring 144 nm in length and 10.5 nm in diameter and consisting of 34 disks. A central channel is also visible in the Tuc2009 tail tube, as is the knobbly appearance reported for λ (Fig. 3A and B). The helical nature of binding of the gold-labeled anti-452009 antibody to the Tuc2009 tail is noteworthy (Fig. 5A), because it is evocative of a sixfold rotational symmetry, as has been noted for the contractile tail of T4 (20).

The polymerization of λ gpV is thought to be facilitated by the action of the gpG and gpGT proteins (23, 35). It has been demonstrated that the predicted protein product of gene t is not translated as a single protein but, rather, as a fusion with the polypeptide encoded by gene g (23). This fusion occurs due to a −1 frameshift at a slippery sequence in the 3′ end of the gpG gene. Neither gpG nor gpGT forms part of the mature lambda virion, leading Levin et al. (23) to propose a chaperone function for these proteins. Xu et al. have recently demonstrated that this slippery sequence is strongly conserved in otherwise nonhomologous tail assembly genes of double-stranded DNA phages (35). Furthermore, it has been stated that the ratio of gpG to gpGT is crucial for the efficient production of biologically active tails, and a specific role for the T domain of the fusion protein is implicated in tail polymerization (35). An analysis of the genome sequences of the Sfi11 and r1t lactococcal phages outlined in Fig. 1 with the Programmed Frameshift Finder program (http://chainmail.bio.pitt.edu/∼junxu/webshift.html) allowed the identification of such slippery sequences in genes analogous to λ g in all cases (data not shown). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the Tuc2009 orf462009 product, gpG2009, was not included in the Tuc2009 virion but was produced during infection, while also highlighting the presence of a second anti-462009 antibody specific protein band, commensurate with that expected for a fusion product of both Orf462009 and Orf472009, gpGT2009 (Fig. 4).

Vegge et al. have recently reported that the double disk baseplate structure of TP901-1, comprised of the BppUTP901-1 (upper disk) and BppLTP901-1 (lower disk) proteins, is essential for infectivity but not crucial for tail morphogenesis (33). Both disks are assembled onto the conical fiber structure, with the lower disk stabilized by the upper. Tuc2009 contains three orf genes within this proposed baseplate submodule (Fig. 1). Immunogold TEM analysis localized the orf512009 protein product to the baseplate region of the Tuc2009 virion and, due to the amino acid similarity between this protein and BppUTP901-1, it was designated BppU2009. The major genetic difference between the Tuc2009 and TP901-1 tail modules is the presence of orf522009 in Tuc2009. Attempts to identify the architectural role fulfilled by the orf522009-encoded protein product using immunogold TEM were unsuccessful and, as outlined above, its genomic location (i.e., between the bppU2009 and bppL2009 genes) has led us to propose that this protein is associated with both the upper baseplate and the lower petticoat structure, possibly in a stabilizing capacity (Fig. 3B). On this basis, it has been designated a baseplate-associated protein (BppA2009). The BppA2009 protein shares two short regions of identity with the protein product of orf552009 (NPS2009), which has been localized to the collar and whisker structure on the Tuc2009 virion (Fig. 3A and 5F). These conserved regions, which are likely to account for the cross-hybridization visible in the Western blot analysis when blots were probed with either the anti-522009 antibody or the anti-552009 antibody (Fig. 4), are also present in proteins of a number of lactococcal and S. thermophilus phages that have been associated with host specificity and tail fiber structures (10, 12, 29). This leads us to speculate that BppA2009 may, in fact, play a role in Tuc2009 host receptor recognition.

The last component of the proposed Tuc2009 baseplate submodule is orf532009. The predicted protein encoded by this ORF shares 50% identity with the first 61 N-terminal amino acids of BppLTP901-1, suggesting that it may constitute the lower baseplate of Tuc2009 and, therefore, it has been designated BppL2009. In support of this assertion, Vegge et al. have recently generated the chimeric phage TP901-1C, in which a part of bppLTP901-1 was exchanged with a part of bppL2009 of Tuc2009 (33). This recombinant phage displayed a host range that was altered from that of the TP901-1 parent and identical to that of Tuc2009, indicating that BppLTP901-1 and BppL2009 play pivotal roles in the determination of TP901-1 and Tuc2009 host specificity, respectively. The distribution of the amino acid similarities between the lower baseplate proteins for the five lactococcal phages outlined in Fig. 1 is interesting and invites speculation as to the teleological nature of these proteins. The three Sfi11 phages, Tuc2009, TP901-1, and ul36, have distinctive host ranges, and the amino acid similarity between their BppL proteins is limited to the N-terminal 55 to 65 amino acids. Similarly, r1t and LC3 are not known to share a common host, and their highly similar BppL proteins differ only in their C termini. Significantly, only TP901-1 and LC3 are known to infect the same host, L. lactis subsp. cremoris 3107, and these are the only two phages that share amino acid similarity in the C termini of their BppL proteins. These observations suggest that it is the C-terminal portion of the BppL proteins that specifies host recognition and that the N-terminal regions are involved in anchoring the lower baseplate on the phage tail. The immunogold data presented here (Fig. 5E) demonstrate that the BppL2009 protein is associated with the lower part of the Tuc2009 baseplate structure and that it is likely to constitute the observed petticoat structure (Fig. 3A, arrow iv).

The gene situated immediately downstream of bppL2009, orf542009, encodes a small hydrophobic protein which is well conserved in P335-type lactococcal phages (Fig. 1). Attempts to overexpress this protein in E. coli in a manner similar to that for the other Tuc2009 tail proteins were unsuccessful and, consequently, polyclonal antibodies could not be generated against it. It has recently been demonstrated that TP901-1 mutant phages lacking the homologous Orf50TP901-1 protein were indistinguishable from the wild type with respect to virion morphology, protein profile, and infection efficiency (32), which indicates that this gene is not essential for TP901-1 propagation. However, the conservation of this Orf protein is interesting, and it is possible that the encoded protein plays a minor role in tail assembly and/or host infection.

The next gene on the Tuc2009 genome (nps2009) encodes a protein that displays homology to proteins of other lactococcal phages that have been described as neck passage structure proteins (3, 5). Immunogold localization of the NPS2009 protein on the Tuc2009 virion revealed that it is situated at the proximal end of the phage tail (Fig. 5F) in the same area as the collar and whiskers (Fig. 3A). The tail gene module of the Sfi11-type phage ul36 is conspicuous in its lack of an nps2009 homolog (Fig. 1), and electron microscopic analysis of the ul36 virion reveals that this phage is not endowed with the collar and whisker structures evident for Tuc2009/TP901-1 (Sylvain Moineau, personal communication). These data lead us to conclude that NPS2009 does, in fact, constitute the collar and whisker structures of Tuc2009. However, the physiological function of this structure is unclear, and its amino acid identity with host specificity and tail fiber structures as outlined above is intriguing. The anatomical location of this structure (i.e., the head-tail interface) lead us to propose that it may be involved the joining of the completed tail to the phage head.

The data presented in this article allow us to advance the model presented by Vegge et al. (32) for TP901-1/Tuc2009 tail morphogenesis while expanding it to include all Sfi11 and r1t-type phages. In this model, Dit2009 acts as the orchestrator of tail morphogenesis whereby IC2009 formation does not occur until sufficient quantities of Dit2009 are present in the cell. When the Dit2009 threshold concentration is reached, both Tal2009 and TMP2009 interact with it to form IC2009. This triggers the polymerization of MTP2009 proximally from IC2009 to form the tail tube. This polymerization is facilitated by the chaperone activity of gpG2009 and gpGT2009, with the length of the tube determined by TMP2009. Tail tube elongation is presumably terminated in a manner similar to that of λ, by the action of proteins encoded by genes upstream of the Tuc2009 tail tube submodule. The baseplates are assembled on the conical IC2009 structure with the petticoat structure constituted by BppL2009 suspended from the saucer-shaped disk formed by BppU2009, with a BppA2009-derived structure possibly stabilizing both baseplates. A fiber formed from Tal2009 protrudes from the bottom of the IC2009 cone and is surrounded by the BppL2009 petticoat (Fig. 3B). Data from the analysis of the TP901-1/Tuc2009 chimera constructed by Vegge et al. (33) indicate that the petticoat structure recognizes specific receptors on the host cell surface, while Kenny et al. (19) have previously demonstrated that the Tal2009 fiber degrades the host cell wall, presumably to facilitate DNA injection. The collar and whisker structure consisting of NPS2009 is thought not to be associated with the Tuc2009 tail and may act to prime the phage head ready for joining of mature tails. (See the supplemental material for an animation outlining the proposed model for Tuc2009 tail morphogenesis [an additional resource is available at http://www.lactococcal-phages.org/gallery/tuc2009/tuc2009-gallery.html].)

Comparative analyses of the structural gene modules of lactococcal phages to λ are nothing new (5-8, 11). However, the degree of anatomical parity between Tuc2009 and λ, despite the lack of any primary amino acid identity, is intriguing and alludes to the evolutionary relatedness of the phages. The data presented in this report have facilitated the discernment of a number of previously unrecognized genetic submodules in the tail genes of lactococcal phages. Gene subsets involved in tail morphogenesis initiation, tail tube elongation, and baseplate formation have been identified, while the architectural role of many of their encoded protein products, along with the nonstructural role of the λ gpG and gpGT homologs, have been elucidated. The model presented for Tuc2009 tail morphogenesis and anatomy is, to our knowledge, the most detailed one presented to date for any phage infecting a gram-positive host. Moreover, with members of the Siphoviridae comprising the most abundant phage morphotype in the environment, the work presented here may be of benefit in assigning anatomical and physiological functions to genes or proteins of phages from a wide variety of sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marjan Terpstra for technical assistance.

This work was funded by Science Foundation Ireland through an investigator grant awarded to Douwe van Sinderen (02/IN1/B198).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, H. W. 1996. Frequency of morphological phage descriptions in 1995. Arch. Virol. 141:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt, E. K., C. Daly, G. F. Fitzgerald, and M. van de Guchte. 1994. Molecular characterization of lactococcal bacteriophage Tuc2009 and identification and analysis of genes encoding lysin, a putative holin, and two structural proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1875-1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blatny, J. M., L. Godager, M. Lunde, and I. F. Nes. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the Lactococcus lactis temperate phage phiLC3: comparative analysis of phiLC3 and its relatives in lactococci and streptococci. Virology 318:231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun, V., Jr., S. Hertwig, H. Neve, A. Geis, and M. Teuber. 1989. Taxonomic differentiation of bacteriophages of Lactococcus lactis by electron microscopy, DNA-DNA hybridization and protein profiles. J. Gen. Microbiol. 181:7291-7297. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brøndsted, L., S. Østergaard, M. Pedersen, K. Hammer, and F. K. Vogensen. 2001. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of the temperate bacteriophage TP901-1: evolution, structure, and genome organization of lactococcal bacteriophages. Virology 283:93-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brüssow, H., and R. W. Hendrix. 2002. Phage genomics: small is beautiful. Cell 108:13-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canchaya, C., C. Proux, G. Fournous, A. Bruttin, and H. Brüssow. 2003. Prophage genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:238-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandry, P. S., S. C. Moore, J. D. Boyce, B. E. Davidson, and A. J. Hillier. 1997. Analysis of the DNA sequence, gene expression, origin of replication and modular structure of the Lactococcus lactis lytic bacteriophage sk1. Mol. Microbiol. 26:49-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello, V. A. 1988. Characterization of bacteriophage interactions in Streptococcus cremoris UC503 and related lactic streptococci. Ph.D. thesis. University College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

- 10.Crutz-Le Coq, A. M., B. Cesselin, J. Commissaire, and J. Anba. 2002. Sequence analysis of the lactococcal bacteriophage bIL170: insights into structural proteins and HNH endonucleases in dairy phages. Microbiology 148:985-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desiere, F., S. Lucchini, C. Canchaya, M. Ventura, and H. Brüssow. 2002. Comparative genomics of phages and prophages in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:73-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duplessis, M., and S. Moineau. 2001. Identification of a genetic determinant responsible for host specificity in Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupont, K., F. K. Vogensen, H. Neve, J. Bresciani, and J. Josephsen. 2004. Identification of the receptor-binding protein in 936-species lactococcal bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5818-5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrix, R. W., and S. R. Casjens. 1974. Protein cleavage in bacteriophage lambda tail assembly. Virology 61:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis, A. W., G. F. Fitzgerald, M. Mata, A. Mercenier, H. Neve, I. B. Powell, C. Ronda, M. Saxelin, and M. Teuber. 1991. Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology 32:2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnsen, M. G., H. Neve, F. K. Vogensen, and K. Hammer. 1995. Virion positions and relationships of lactococcal temperate bacteriophage TP901-1 proteins. Virology 212:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsura, I. 1976. Morphogenesis of bacteriophage lambda tail. Polymorphism in the assembly of the major tail protein. J. Mol. Biol. 107:307-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsura, I. 1983. Tail assembly and injection, p. 331-346. In R. W. Hendrix, J. W. Roberts, F. W. Stahl, and R. A. Weisberg (ed.), LAMBDA II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Kenny, J. G., S. McGrath, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 2004. Bacteriophage Tuc2009 encodes a tail-associated cell wall-degrading activity. J. Bacteriol. 186:3480-3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostyuchenko, V. A., P. R. Chipman, P. G. Leiman, F. Arisaka, V. V. Mesyanzhinov, and M. G. Rossmann. 2005. The tail structure of bacteriophage T4 and its mechanism of contraction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:810-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiman, P. G., S. Kanamaru, V. V. Mesyanzhinov, F. Arisaka, and M. G. Rossmann. 2003. Structure and morphogenesis of bacteriophage T4. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:2356-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin, M. E., R. W. Hendrix, and S. R. Casjens. 1993. A programmed translational frameshift is required for the synthesis of a bacteriophage lambda tail assembly protein. J. Mol. Biol. 234:124-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lubbers, M. W., N. R. Waterfield, T. P. Beresford, R. W. Le Page, and A. W. Jarvis. 1995. Sequencing and analysis of the prolate-headed lactococcal bacteriophage c2 genome and identification of the structural genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4348-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath, S., J. F. Seegers, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 1999. Molecular characterization of a phage-encoded resistance system in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1891-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen, M., S. Østergaard, J. Bresciani, and F. K. Vogensen. 2000. Mutational analysis of two structural genes of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1 involved in tail length determination and baseplate assembly. Virology 276:315-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proux, C., D. van Sinderen, J. Suarez, P. Garcia, V. Ladero, G. F. Fitzgerald, F. Desiere, and H. Brüssow. 2002. The dilemma of phage taxonomy illustrated by comparative genomics of Sfi21-like Siphoviridae in lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:6026-6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Seegers, J. F., S. Mc Grath, M. O'Connell-Motherway, E. K. Arendt, M. van de Guchte, M. Creaven, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 2004. Molecular and transcriptional analysis of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage Tuc2009. Virology 329:40-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stuer-Lauridsen, B., T. Janzen, J. Schnabl, and E. Johansen. 2003. Identification of the host determinant of two prolate-headed phages infecting Lactococcus lactis. Virology 309:10-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsui, L. C., and R. W. Hendrix. 1983. Proteolytic processing of phage lambda tail protein gpH: timing of the cleavage. Virology 125:257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vegge, C. S., L. Brøndsted, H. Neve, S. Mc Grath, D. van Sinderen, and F. K. Vogensen. 2005. Structural characterization and assembly of the distal tail structure of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J. Bacteriol. 187:4187-4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vegge, C. S., F. K. Vogensen, S. Mc Grath, H. Neve, D. van Sinderen, and L. Brøndsted. 2006. Identification of the lower baseplate protein as the antireceptor of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophages TP901-1 and Tuc2009. J. Bacteriol. 188:55-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, J., M. Hofnung, and A. Charbit. 2000. The C-terminal portion of the tail fiber protein of bacteriophage lambda is responsible for binding to LamB, its receptor at the surface of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 182:508-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, J., R. W. Hendrix, and R. L. Duda. 2004. Conserved translational frameshift in dsDNA bacteriophage tail assembly genes. Mol. Cell 16:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.