Abstract

The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) is the major carbohydrate transport system in oral streptococci. The mannose-PTS of Streptococcus mutans, which transports mannose and glucose, is involved in carbon catabolite repression (CCR) and regulates the expression of known virulence genes. In this study, we investigated the role of EIIGlc and EIIABMan in sugar metabolism, gene regulation, biofilm formation, and competence. The results demonstrate that the inactivation of ptsG, encoding a putative EIIGlc, did not lead to major changes in sugar metabolism or affect the phenotypes of interest. However, the loss of EIIGlc was shown to have a significant impact on the proteome and to affect the expression of a known virulence factor, fructan hydrolase (fruA). JAM1, a mutant strain lacking EIIABMan, had an impaired capacity to form biofilms in the presence of glucose and displayed a decreased ability to be transformed with exogenous DNA. Also, the lactose- and cellobiose-PTSs were positively and negatively regulated by EIIABMan, respectively. Microarrays were used to investigate the profound phenotypic changes displayed by JAM1, revealing that EIIABMan of S. mutans has a key regulatory role in energy metabolism, possibly by sensing the energy levels of the cells or the carbohydrate availability and, in response, regulating the activity of transcription factors and carbohydrate transporters.

Streptococcus mutans is the primary etiological agent of dental caries in humans. The abilities to form biofilms, scavenge and catabolize a wide range of carbohydrates, and tolerate major fluctuations in nutrient availability and pH are considered crucial for the organism to survive, persist, and cause caries (19). The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) is the major carbohydrate transport system in oral streptococci, especially under carbohydrate-limiting conditions (39, 48). The PTS consists of two general proteins, enzyme I (EI), which is encoded by the ptsI gene, and the heat-stable phosphocarrier protein HPr, which is encoded by the ptsH gene. In addition, various sugar-specific permeases, known as enzyme II (EII) complexes, are responsible for the concomitant phosphorylation and internalization of many different sugars. The EII complexes are composed of three domains, A, B, and C, which can exist in a single polypeptide or as separate proteins, depending on the organism and cognate sugar (22, 35). In the case of the EII enzyme for mannose, a fourth domain, D, can be present. The A and B domains are responsible for the phosphorylation of the cognate sugars, whereas the C and D domains comprise the membrane-associated permeases.

PTS components not only participate in sugar uptake, but also influence many other cellular processes, including biofilm formation, chemotaxis, alkali generation, carbon catabolite repression (CCR), and virulence gene expression (1, 10, 28, 30, 35, 49). The glucose-PTS of Escherichia coli, EIIGlc, controls CCR and regulates the expression of rpoS, which encodes the sigma factor (σ32) that is central to stress responses in this and related organisms (35, 42, 46). In Streptococcus salivarius, mutations in the manL gene, encoding the EIIABLMan, have pleiotropic effects on gene expression, including a dramatically altered proteome, the loss of diauxic growth, and altered PTS activity for various sugars (48). In S. mutans, the mannose-specific PTS is encoded by three genes (manLMN) arranged in an operon. The manL gene codes for the EIIABMan domain, whereas the manMN genes code for the C and D domains, respectively. A putative manO homologue, which was initially identified as part of the man operons of Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus bovis, is located approximately 2 kbp downstream of manLMN in S. mutans (1, 5, 29). No function has been assigned to ManO, although it has been speculated that this protein could interact with nucleic acids (11). The mannose-PTS of S. mutans was demonstrated to take up glucose, mannose, and the glucose analog 2-deoxy-glucose (1, 25-27). In addition, Streptococcus mutans JAM1, which lacks EIIABMan of the mannose-PTS (manL), did not display diauxic growth in the presence of glucose and a nonpreferred sugar, suggesting that EIIABMan has a central role in CCR (1). The strain lacking EIIABMan also had lower levels of expression of the exopolysaccharide-forming glucosyltransferases (gtfBC), indicating an involvement in the regulation of sucrose-dependent biofilm formation and virulence (1). Two-dimensional gels of JAM1 revealed that the loss of EIIABMan affected the synthesis of many proteins (1). In the present study, we continued investigating the contribution of sugar-specific components of the PTS to sugar metabolism, virulence, and gene regulation in S. mutans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. mutans strains listed in Table 1 were maintained in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. When required, 10 μg ml−1 erythromycin (Em) or 1 mg ml−1 kanamycin (Km) was added to the growth medium. To grow cells for enzymatic assays and to assess the ability of cells to grow in different sugar sources, tryptone-vitamin base (TV) medium (9) supplemented with the desired carbohydrate was used.

TABLE 1.

S. mutans strains used in this study

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from S. mutans UA159 as previously described (8). Restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were obtained from Invitrogen (Gaithersburg, MD) and New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA). PCRs were carried out with 100 ng of chromosomal DNA using iTaq DNA polymerase (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). DNA was introduced into S. mutans by natural transformation with the addition of 5 to 10 μmol of competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) (23). Southern blot analysis was carried out at a high stringency as recommended by the supplier of the labeling and detection kits (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX).

Inactivation of ptsG.

The ptsG gene (2,187 bp), which encodes a putative EIIGlc, was inactivated with an Em resistance cassette inserted 70 bp downstream of the start codon in S. mutans UA159 by using PCR ligation mutagenesis (16). The 5′ portion of ptsG and upstream sequences were amplified by PCR using a pair of primers designated PtsG23S (5′-CACAGGCTTTACAGATTG-3′) and PtsG565ASHindIII (5′-CCATTAAACaagcttCGAATTTTTGC-3′), generating a 542-bp product that was subsequently digested with HindIII. The 3′ portion of the gene was amplified with the primers PtsGS570KpnI (5′-CGGAAAATggtaccTGGTTGTTATTG-3′) and PtsGAS1168 (5′-CGGTATGTTGTGAAGAAG-3′), generating a 598-bp product that was digested with KpnI. Lowercase letters indicate the restriction enzyme site added to the primer sequence.) Each digested fragment was ligated to a HindIII/KpnI-digested Em resistance cassette. The resulting ligation was used to transform S. mutans UA159 to generate strain MMC1.

Construction of reporter gene fusions and CAT assays.

Genomic DNA from MMC1 was used to transform TW31 (50), a UA159-derivative strain containing the promoter of the fructan hydrolase gene (fruA) of S. mutans fused to a cat gene, to generate strain JAM25. To measure chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity driven from the fruA promoter in the wild-type (TW31) and EIIglc-deficient strains (JAM25), cells were grown in 50 ml of TV plus 0.5% galactose or TV plus 0.5% galactose plus 0.5% inulin to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4. Cells were harvested, washed with an equal volume of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), and resuspended in 750 μl of the wash buffer. The cells were homogenized by bead beating twice for 40 s, with cooling on ice for 2 min after each cycle. The cleared lysates were used to determine CAT activity by the spectrophotometric method of Shaw et al. (41).

Biofilm and PTS assays.

The ability of the wild-type and mutant strains to form stable biofilms in the presence of glucose or sucrose was assessed as described elsewhere (3). Permeabilized cells of S. mutans strains that had been grown in TV medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose, mannose, fructose, or lactose to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 were assayed for sugar-specific PTS activity as described elsewhere (17).

Transformation assay.

The transformation efficiencies of UA159, MMC1, and JAM1 were assessed. Briefly, cells were grown in BHI plus 10% (vol/vol) horse serum at 37°C in 5% CO2, 95% air to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.2. CSP (23) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 10 μmol ml−1 and incubated for 20 min, followed by the addition of plasmid DNA at a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1. To assess the transformation efficiency of JAM1, pJL78, a plasmid containing the relA gene disrupted by an Em marker, was used (20). MMC1 was transformed with pJA8, which is a plasmid that contains the galK gene disrupted by a Km marker (2). S. mutans UA159 was transformed with both plasmids independently. After the addition of plasmid DNA, cells were incubated for 3 h and then plated on BHI plates for total cell counts and on BHI supplemented with Em or Km to enumerate transformants. Colonies were counted after 48 h, and transformation efficiency was expressed as the percentage of transformants among the total viable recipient cells.

Two-dimensional electrophoresis.

Protein lysates were prepared from S. mutans UA159 and MMC1 that were grown in 100 ml of BHI broth to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 and processed as previously described (1). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was performed at Kendrick Labs, Inc. (Madison, WI), according to the method of O'Farrell (32), and the gels were silver stained. Densitometric analysis was used to compare the intensities of the spots.

RNA isolation.

RNA from S. mutans cells was isolated as described elsewhere (7) with some modifications. Briefly, 50-ml cultures that were intended for use in either microarrays or real-time PCR experiments were grown under the desired conditions and harvested by centrifugation at 4°C. Pelleted cells were resuspended in 400 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, 800 μl of RNA protect reagent (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA) was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 5 min with vortexing for 10 s at 1-min intervals. Cells were then pelleted, resuspended in 500 μl Tris-EDTA (50:10) buffer, and transferred to 1.5-ml screw-cap tubes containing sterile glass beads (avgerage diameter, 0.1 mm; Biospec, Bartlesville, OK), 100 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 650 μl of acid phenol:chloroform (5:1). The mixture was homogenized twice in a bead beater for 40 s and chilled on ice for 2 min between cycles. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at maximum speed at 4°C. Two additional hot acid-phenol:chloroform extractions were performed by incubating the samples at 65°C for 10 min and transferring them to an ice bath for another 10 min, followed by centrifugation at maximum speed for 10 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was collected and extracted once with chloroform:isoamyl-alcohol (24:1). RNA was precipitated with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5, and an equal volume of isopropanol at −20°C for 1 h, followed by multiple washes with 70% ethanol, one wash with 99% ethanol, and drying in vacuo. RNA was resuspended in 52 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water; 1 μl was used to estimate RNA concentration, and 1 μl was used to verify RNA quality in a formaldehyde gel. The remaining 50-μl sample was digested with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX), and then the RNA was repurified and treated on column with DNase I using an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA) as recommended by the supplier. RNA concentration was estimated spectrophotometrically in triplicate. One microgram of RNA was run in a formaldehyde gel to verify RNA quality and to validate the concentration estimates.

Microarray experiments.

S. mutans UA159 microarrays were provided by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). The microarrays consisted of 1,948 70-mer oligonucleotides representing 1,960 open reading frames. The full 70-mer complement is printed four times on the surface of each microarray slide. Additional details regarding the arrays are available at http://pfgrc.tigr.org/descriptions/S_mutans.shtml. A reference RNA that had been isolated from 2 liters of UA159 cells grown in BHI broth to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 was used in every experiment. The reference RNA was purified as above, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. Our experimental conditions consisted of S. mutans UA159 and JAM1 grown in BHI broth and collected at the mid-exponential phase of growth (optical density at 600 nm = 0.5). All RNAs were purified as described above and used to generate cDNA according to the protocol provided by TIGR at http://pfgrc.tigr.org/protocols.shtml with the following minor modifications. The amount of RNA in each reaction was increased to 10 μg, and the molar ratio of dTTP:aa-dUTP was increased to 1:1.5. In addition, SuperscriptIII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) was used to increase cDNA yields. Purified UA159 and JAM1 cDNAs were coupled with indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-dUTP, while reference cDNA was coupled with indodicarbocyanine (Cy5)-dUTP (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Six individual Cy3-labeled cDNA samples originating from six different cultures of UA159 or JAM1 were hybridized to the arrays along with Cy5-labeled reference cDNA, generating a total of 12 slides. Hybridizations were carried out in the dark for 17 h at 42°C. The slides were then washed according to TIGR protocols and scanned using a GenePix scanner (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA) at 532 nm (Cy3 channel) and 635 nm (Cy5 channel). The sensitivity of the photomultiplier tube was adjusted during prescanning at 33% of full power in order to obtain a Cy3:Cy5 ratio of 1:1.

S. mutans microarray data analysis.

After the slides were scanned, single-channel images were loaded into TIGR Spotfinder software (http://www.tigr.org/software/) and overlaid. A spot grid was created according to TIGR specifications and then manually adjusted to fit all spots within the grid. The intensity values of each spot were measured and saved into “.mev” and “.tav” files. Data were normalized using LOWESS and iterative log mean centering with default settings, followed by in-slide replicate analysis using TIGR microarray data analysis software (MIDAS; http://www.tigr.org/software/). Spots that were flagged as bad because of either low intensity values or signal saturation were automatically discarded. Statistical analysis was carried out using BRB array tools (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html) with a cutoff P value of 0.001.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was used to validate microarray experiments. Four independent RNA samples from UA159 and JAM1 grown in BHI to an optical density of 0.5 were isolated as detailed above. One microgram of RNA and the iScript cDNA synthesis kit containing random primers (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used to generate cDNA. Gene-specific primers (see Table 3) used in all real-time PCR experiments were designed using Beacon Designer 2.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). Standard curves for each gene were prepared as described elsewhere (52).

TABLE 3.

Genes differentially expressed in JAM1a

| Unique ID (GenBank) | Description | Microarray difference (n-fold) of geom means JAM1/UA159 | Microarray parametric P value | Real-time PCR fold difference of geom means JAM1/UA159 | Real-time PCR parametric P value | Real-time PCR primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMU.1596 | Putative PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIC component | 132.429 | P < 1E−07 | 1,111.11 | 0.002 | F-GGCTGGGCAATGAGTAATGG, R-TGACAAAACCAGGGATTAAAGC |

| SMU.1601 | Putative phospho-beta-glucosidase BglA | 100.611 | 5.83E−05 | |||

| SMU.148 | Putative alcohol-acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | 35.146 | 3.00E−07 | 15.4 | 0.031 | F-AACGGTTGGCATCATTGGTG, R-TGTTGGGTTAGTTGTTGGTACG |

| SMU.1598 | Putative PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIA component | 26.114 | 0.0021912 | 474.72 | 0.0087 | F-GAATTACAAGTTGCCGCATTTG, R-TCTGTGCTTGATGAGCTTTGAG |

| SMU.1411 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 23.54 | 3.40E−06 | |||

| SMU.936 | Putative amino acid ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 18.147 | 9.41E−05 | |||

| SMU.962 | Putative dehydrogenase | 13.452 | 0.000102 | |||

| SMU.934 | Putative amino acid ABC transporter, permease protein | 12.95 | 0.0005141 | 3.6 | 0.000062 | F-AGAAGCTGGTCTCAGTATTGG, R-ACCGATTGTATAGGCTAGAGC |

| SMU.1536 | Putative starch (bacterial glycogen) synthase | 12.283 | 4.70E−06 | |||

| SMU.935 | Putative amino acid ABC transporter, permease protein | 10.91 | 0.000406 | |||

| SMU.114 | Putative PTS system, fructose-specific IIBC component | 10.529 | 0.0022656 | 7.0 | 0.0067 | F-AGCCGACAAGGATGTTCAAGC, R-CTTTGCCAGCTAAAGCATCTGC |

| SMU.1537 | Putative glycogen biosynthesis protein GlgD | 10.407 | 1.95E−05 | 15.3 | 0.0046 | F-GCTATCGGATTCCCAGAAATGG, R-CACGACCGCTTCTGATATGATC |

| SMU.933 | Putative amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino | 10.22 | 0.0008668 | |||

| SMU.496 | Putative cysteine synthetase A O-acetylserine lyase | 9.668 | 3.22E−05 | |||

| SMU.961 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 9.191 | 0.0008401 | 4.6 | 0.0048 | F-AACGGCTCTTGAGACTTATCG, R-TCTGGTGCCATTTGAATTTGC |

| SMU.180 | Putative oxidoreductase possible fumarate reductase | 8.948 | 0.0001778 | |||

| SMU.402 | Pyruvate formate-lyase | 8.655 | 1.03E−05 | 11.5 | 0.019 | F-AAGGAACTGACTGGAAAGAC, R-CGTGTTTCTTCGTAATGCG |

| SMU.2127 | Putative succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 7.895 | 0.0017855 | |||

| SMU.149 | Putative transposase | 7.866 | 0.0017717 | |||

| SMU.1538 | Putative glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase | 7.444 | 6.80E−06 | |||

| SMU.1535 | Glycogen phosphorylase | 7.129 | 9.36E−05 | |||

| SMU.312 | PTS system, sorbitol phosphotransferase enzyme IIBC | 6.326 | 4.50E−06 | 10 | 0.07 | F-TCGCTCTGGCTATTGTTGACTG, R-TGGGCTAAAGGTCCGCTCTTAC |

| SMU.1077 | Putative phosphoglucomutase | 5.515 | 1.37E−05 | 4.1 | 0.03 | F-ATTGGCGCTGGAACTAATCG, R-TTGAGAGAAATGACGGGAATCG |

| SMU.527 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4.988 | 2.79E−05 | |||

| SMU.616 | Hypothetical protein | 4.842 | 6.19E−05 | |||

| SMU.1422 | Putative pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit | 4.835 | 0.0028314 | |||

| SMU.179 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4.762 | 0.0005658 | 4.55 | 0.012 | F-ATGATTGTGGGCTGTTCG, R-CGTGTTCAGAGTGACCTAG |

| SMU.1603 | Putative lactoylglutathione lyase | 4.533 | 0.0022774 | |||

| SMU.508 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4.498 | 0.0028192 | |||

| SMU.1013c | Putative Mg2+/citrate transporter | 4.46 | 0.0009883 | |||

| SMU.308 | Sorbitol-6-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase | 4.196 | 0.0010415 | |||

| SMU.1187 | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | 4.037 | 5.20E−05 | |||

| SMU.1254 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4 | 0.0022115 | |||

| SMU.360 | Extracellular glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 3.973 | 0.0011203 | |||

| SMU.675 | Phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system enzyme I, PTS system | 3.813 | 8.10E−06 | 1.6 | 0.014 | F-GCAGTAGATACCCTTGGTGAAG, R-TCTGTCACTTCTTTGAGAGCAC |

| SMU.460 | Putative amino acid ABC transporter, permease | 3.723 | 0.0001489 | |||

| SMU.426 | Copper-transporting ATPase P-type ATPase | 3.271 | 0.0007648 | |||

| SMU.882 | Multiple sugar-binding ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein, MsmK | 3.161 | 0.0006518 | |||

| SMU.361 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 3.141 | 0.0001563 | |||

| SMU.674 | Phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system HPr | 3.066 | 0.0007686 | 1.7 | 0.01 | F-CATGCACGCCCAGCTACTTTG, R-CATCAGCACCTTGACCAACACC |

| SMU.1247 | Putative enolase | 2.851 | 0.0001529 | 0.48 | 0.07 | F-TGGTTCCTTCAGGAGCTTCTAC, R-CCGTCAAGTGCGATCATTGC |

| SMU.509 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.845 | 0.0006042 | 0.73 | 0.2 | F-GTTGGTCAGGTTCGACAAGC, R-TGGATACTTGGCAAAAGGATGG |

| SMU.1943 | Putative leucyl-tRNA synthetase | 2.643 | 0.0019886 | |||

| SMU.859 | Putative carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, small subunit | 2.373 | 0.0024238 | |||

| SMU.1115 | Lactate dehydrogenase | 2.332 | 0.000617 | |||

| SMU.1563 | Putative cation-transporting P-type ATPase PacL | 2.135 | 0.0014719 | |||

| SMU.1856c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.415 | 0.0015245 | |||

| SMU.613 | Hypothetical protein | 0.361 | 0.0018835 | |||

| SMU.1009 | Putative histidine kinase | 0.301 | 0.0007651 | |||

| SMU.2097 | Hypothetical protein | 0.295 | 0.0023821 | |||

| SMU.1516 | Putative histidine kinase CovS VicK homolog | 0.284 | 0.0004549 | 0.55 | 0.017 | F-CCTTAAACCGCCGTGAAAGTGG, R-AGGGCACCATCGTCCAAAGC |

| SMU.1432c | Putative endoglucanase precursor | 0.279 | 0.000974 | |||

| SMU.131 | Putative lipoate-protein ligase | 0.259 | 0.00074 | |||

| SMU.128 | Putative acetoin dehydrogenase (TPP-dependent), E1 component beta | 0.256 | 0.0015098 | |||

| SMU.1744 | Putative 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase III | 0.253 | 0.0013806 | 0.52 | 0.014 | F-AGTTATCGGTGCAGAAGTTC, R-AAAGGGTGACGAAACAGC |

| SMU.2042 | Dextranase precursor | 0.208 | 6.26E−05 | 0.23 | 0.003 | F-TTATTCCTGCAAACTCCTTAGC, R-ACCTCCAATAGCAGCATAACG |

| SMU.872 | Putative PTS system, fructose-specific enzyme IIABC component | 0.181 | 0.0003632 | 0.11 | 0.045 | F-TTAAGGCTGGGATCATGAATCG, R-AACAGGTTCACCATCAAGAGC |

| SMU.1926 | Putative transcriptional regulator | 0.177 | 0.0026323 | |||

| SMU.2038 | Putative PTS system, trehalose-specific IIABC component | 0.161 | 0.0003789 | 0.12 | 0.005 | F-GTATTGAAGGGGTCTCTAAGG, R-ATTACGAAATCCAAGAATCAGC |

| SMU.602 | Putative sodium-dependent transporter | 0.157 | 0.002202 | |||

| SMU.870 | Putative transcriptional regulator of sugar metabolism | 0.131 | 0.0007458 | |||

| SMU.871 | Putative fructose-1-phosphate kinase | 0.108 | 0.0004296 |

ID, identification number; geom, geometric; F, forward; R, reverse.

RESULTS

Physiological characteristics of MMC1 and JAM1.

A search of the S. mutans genome (4) annotated at the oral pathogens sequence database (http://www.oralgen.lanl.gov/) showed only one gene, SMu1858 (oralgen annotation; SMU.2047c, GenBank annotation), with similarity to the previously characterized EIIGlc of Bacillus subtilis (44). The EIIGlc of S. mutans is 69% identical (81% similar) to a probable glucose-specific EIIABC of Streptococcus pneumoniae and 34% identical (54% similar) to the EIIGlc of Bacillus subtilis (44). A BLAST search of PtsG of B. subtilis against the S. mutans database revealed that SMu1858 shares the highest degree of similarity, and that other open reading frames did not share high levels of similarity with the query protein.

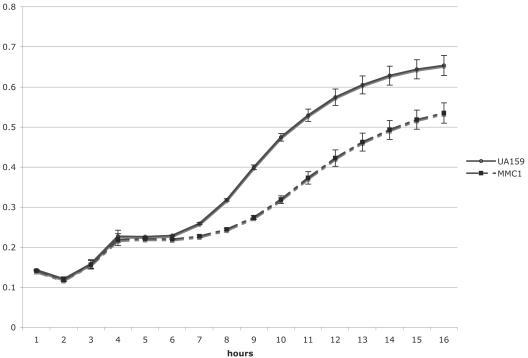

To determine the impact of the absence of a functional EIIGlc on the ability of S. mutans to metabolize sugars, MMC1 was grown in TV medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose, fructose, mannose, lactose, galactose, or sorbitol. The ptsG knockout strain, MMC1, did not display altered growth relative to the wild-type strain on any of the sugars tested (data not shown). PTS activity was measured in UA159, MMC1, and JAM1 cells that were grown in TV medium supplemented with various carbohydrate sources. No differences were seen in glucose, fructose, mannose, lactose, or sorbitol PTS activity (data not shown) when MMC1 was grown in glucose or fructose. Also, MMC1 displayed diauxic growth in the presence of glucose and the nonpreferred carbohydrate inulin (Fig. 1), suggesting that, unlike EIIMan, EIIGlc is not involved in CCR in S. mutans. Interestingly, the utilization of inulin by MMC1 was less efficient than that by UA159 (Fig. 1), suggesting that EIIGlc may exert regulatory control over the expression of fructan hydrolase encoded by the fruA gene.

FIG. 1.

Diauxic growth of UA159 and MMC1 in TV medium supplemented with 0.05% glucose and 0.5% inulin. The circles represent the wild-type strain UA159, whereas the squares represent MMC1, the ptsG knockout strain. The results shown represent the means and standard deviations (error bars) of three independent experiments.

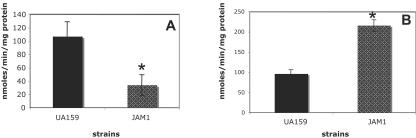

The growth characteristics of JAM1, the manL knockout strain, in glucose, fructose, and mannose were consistent with our earlier observations (1), which revealed that the growth rate of JAM1 was lower in glucose, higher in mannose, and similar to that of the wild-type strain in fructose. With the inclusion in this study of additional carbohydrates that had not been previously tested, it was noted that the doubling time of JAM1 in TV supplemented with 0.5% galactose was 408.3 min (±10.4), compared to 230.4 min (±13.3) for S. mutans UA159. Notably, the growth rate of JAM1 on lactose was similar to that of UA159, with doubling times of 116.7 ± 5.8 and 120 ± 5 min, respectively. JAM1 grew much faster in 0.5% sorbitol than did UA159, with doubling times of 216.7 ± 7.6 and 330 ± 25 min, respectively. The level of lactose-PTS activity in JAM1 grown on glucose was threefold lower than that observed for UA159 (P = 0.002) (Fig. 2A). Also of note (Fig. 2B), when cells were grown in the presence of glucose, the activity of the cellobiose-PTS in JAM1 was twofold higher than that observed for UA159 (P = 0.003).

FIG. 2.

Lactose-specific (A) and cellobiose-specific (B) PTS activities of UA159 and JAM1 cells grown in glucose. The asterisk represents a statistically significant P value of ≤0.05. The results shown represent the means and standard deviations (error bars) of three independent experiments.

Effects of EIIGlc on gene expression.

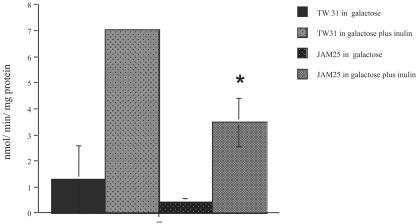

The fruA gene product is an exo-β-d-fructosidase or fructanase enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of extracellular homopolymers of fructose into free fructose (8), which can enter the cell via the fructose-PTS. EIIGlc does not appear to be involved in the regulation of the fructose-PTS, as MMC1 did not display altered growth rates in fructose and had wild-type levels of fructose-PTS activity. However, the observation that MMC1 grows slower on inulin led us to investigate whether EIIGlc could be involved in the regulation of fruA. Strains carrying a cat gene fusion to the fruA promoter were grown in TV medium supplemented with the nonrepressing sugar galactose (0.5%), with or without 0.5% inulin. We observed a 50% reduction (P = 0.02) in CAT activity expressed from the fruA promoter in JAM25 (ptsG-minus background) relative to the wild-type background (TW31) in cells grown in the presence of inulin (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

CAT specific activity driven by fruA promoter in the wild-type (TW31) and ptsG-minus (JAM 25) backgrounds. Cells were grown in TV supplemented with galactose or galactose plus inulin. Values shown are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from at least three independent experiments. The results are expressed as nanomoles of Cm acetylated per minute per milligram of protein.

In addition to changes in the expression of fruA, an effect on the protein profile of cells lacking EIIGlc was evident in two-dimensional gels that were silver stained, revealing that at least 14 proteins were up-regulated and 12 were down-regulated in the ptsG-minus strain (data not shown).

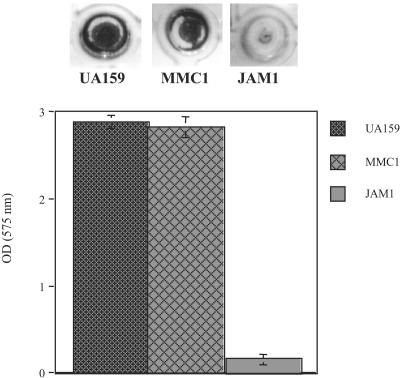

Role of EIIABMan and EIIGlc in biofilm formation.

When using transposon mutagenesis to search for genes involved in biofilm formation in Streptococcus gordonii, Loo and colleagues (28) noted that insertions into the gene for an inducible fructose-PTS caused decreases in biofilm accumulation. In the present study, we investigated the role of EIIABMan and EIIGlc in biofilm formation in the presence of glucose and sucrose. Figure 4 shows that JAM1 had an impaired capacity to form biofilms in the presence of glucose, but the strain lacking ptsG did not display altered biofilm formation under these conditions. Neither mutant strain showed a significant difference in biofilm formation when grown in the presence of sucrose (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Biofilm formation (top) and biofilm biomass quantitation (bottom) of S. mutans UA159, MMC1 (ptsG knockout), and JAM1 (manL knockout) in buffered medium supplemented with glucose. The results shown represent the means and standard deviations (error bars) of at least three independent experiments.

Diminished transformation efficiency of JAM1.

Several competence-related genes are known to contribute to the ability of S. mutans to form biofilms (3, 24). Also, as we noted previously (1), a gene with significant similarity to comA, which is involved in the secretion of CSP (33), lies immediately downstream of the manLMN operon in S. mutans. Because of the pleiotropic effects of the loss of EIIABMan and EIIGlc on gene expression and virulence properties, we investigated whether these enzymes affected the ability of cells to be transformed by DNA with resident homology in the chromosome. S. mutans MMC1 did not show any changes in the ability to be transformed (Table 2). However, when JAM1 was transformed in the absence of CSP, an average reduction of 81% in the total number of transformants was observed (Table 2). As expected, the addition of CSP resulted in an increase of about 1,000-fold in the overall transformation efficiency, but JAM1 still showed a reduction of 64% in the number of transformants relative to UA159 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Transformation frequency of S. mutans strains in the presence of horse serum or horse serum plus 10 nmol of CSP

| Strain | % Competence frequency in the presence of HSa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without CSP | With CSP | |

| UA159 | 100 | 100 |

| JAM1 | 19.0 (±21.6) | 35.9 (±25.6) |

| MMC1 | 64.4 (±44.5) | 91.1 (±35.2) |

The numbers presented here are the means (±standard deviations) of at least three independent experiments. HS, horse serum.

The transcriptome of JAM1 reveals that EIIABMan has a major impact on energy metabolism.

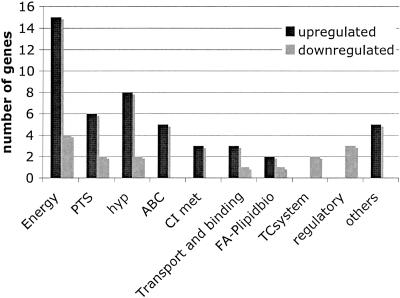

Unlike EIIGlc, EIIABMan of S. mutans has an important role in multiple cellular processes, including CCR, biofilm formation, and competence. These findings, supported by our previous work with S. mutans UA159 (1) and the extensive work of Vadeboncoeur and colleagues with other oral streptococci (11, 29, 47, 48), provided a strong rationale to apply microarrays to explore how gene expression was affected on a more global scale in JAM1. Table 3 shows that, under the growth conditions tested, 62 genes displayed altered expression levels in JAM1 relative to UA159 with a P value of ≤0.003. Among these genes, 27 (43.5%) participate in energy metabolism, 8 encode components of the PTS, and 10 were hypothetical proteins (Fig. 5). Notably, a putative cellobiose-specific IIC component of the PTS (SMU.1596) showed the greatest change in expression, 132-fold, in the EIIABMan knockout strain. Also, a putative phospho-β-glucosidase, encoded by bglA, that is responsible for the breakdown of β-glucosides, such as esculin, cellobiose, and salicin (12), was up-regulated 100-fold in JAM1. The genes involved in glycogen anabolism (SMU.1535 to 1538), glgCDAP, were also up-regulated at least sevenfold in JAM1. Interestingly, the histidine kinase covS/vicK gene (SMU.1516), which regulates the expression of several genes involved in biofilm formation, was down-regulated 3.5-fold in JAM1. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR of 20 genes was performed to validate microarray data, revealing that 18 genes displayed the same trend observed in the microarrays (Table 3). Because real-time quantitative RT-PCR is a much more sensitive technique, some discrepancy in the relative levels of RNA from the two strains between microarray and real-time PCR data was expected.

FIG. 5.

Number of genes, grouped in functional categories, that are differentially expressed in JAM1 relative to UA159 grown in BHI broth to an optical density of 0.5. The clusters of orthologous group functional categories are as follows: energy, energy metabolism; PTS, phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (also belongs to energy metabolism); hyp, hypothetical protein; ABC, ABC transporters; CI met, central and intermediate metabolism; transport and binding, transport and binding of metals and cations; FA-plipidbio, fatty acid and phospholipid biosynthesis; TC system, two-component systems; regulatory, transcriptional regulators; others, genes that do not belong to any of the categories described above.

DISCUSSION

In many bacteria, EIIGlc is a central regulator of global gene expression through CCR by allosterically regulating the activity of other enzymes, PTS porters, and regulatory proteins (15). Previously, we demonstrated that the mannose-PTS plays important roles in sugar metabolism, CCR, and virulence gene expression in S. mutans (1). In conjunction with the findings presented in this study, it appears that EIIABMan, but not EIIGlc, is a key component in the regulation of energy metabolism. Our data also revealed that EIIABMan profoundly influenced CCR, PTS activity, biofilm formation, and genetic competence, whereas EIIGlc has a negligible influence on these traits.

The comparisons of PTS activities in the parental and MMC1 strains revealed that EIIGlc is not a major glucose porter in S. mutans and does not exert an important role in the regulation of other PTS enzymes. On the other hand, the inactivation of ptsG does seem to have a considerable effect on the proteome. Thus, it is likely that the EIIGlc enzyme exerts an influence on the expression or activity of other genes and gene products in the cell. It is of interest that EIIGlc impacts the expression of fructanase (fruA), which is known to be induced by the presence of its substrates, levans and inulins, but also to be negatively regulated by CCR and the fructose-PTS (51). A lack of any effect of the loss of EIIGlc on diauxic growth suggests that this PTS enzyme has little influence on CCR in S. mutans UA159. Therefore, it is possible that EIIGlc regulates the ability of components of the PTS to negatively regulate fruA expression without dramatically influencing measurable fructose-PTS activity. Further studies on the interplay of EIIGlc and EIIFru enzymes are warranted. Interestingly, the inactivation of EIIABMan has the opposite effect that the loss of EIIGlc has on fruA transcription (unpublished data), possibly because of the alleviation of CCR in JAM1. Thus, it appears that multiple PTS enzymes can exert different regulatory functions to orchestrate carbohydrate catabolism in response to nutrient source and availability.

Early studies reported that the glucose/mannose-PTS of S. mutans could regulate the uptake of glucose and lactose and possibly other sugars (25-27). Interestingly, JAM1 was able to grow faster than UA159 in sorbitol and had altered levels of lactose and cellobiose-PTS activity compared to that of the wild type. Microarray data revealed that the cellobiose-PTS and phospho-beta-glucosidase had the greatest severalfold change in the expression in JAM1 (Table 3). The cellobiose-PTS phosphorylates and transports β-glucosides (cellobiose, salicin, and arbutin), whereas phospho-β-glucosidase, encoded by bglA, is responsible for the breakdown of β-glucosides. In S. mutans, the bglA gene flanks the genes for the β-glucoside-specific EII (cellobiose-PTS), is induced by the presence of β-glucosides, and is subject to CCR (12). Thus, it is possible that the cellobiose-PTS and the bgl operon are subject to the same regulatory mechanisms. It is also possible that EIIABMan could control the expression of the entire bgl regulon through CCR. Mechanistically, it is likely that the influence of EIIABMan on PTS activities could be exerted through the phosphorylation state of regulatory proteins controlling PTS gene transcription or that EIIABMan directly interacts with other porters to allosterically control their activity, as has been observed with EIIGlc of E. coli and IIACrr of Streptomyces coelicolor (15). We have initiated studies to better understand how EIIMan exerts its influence on such a wide array of gene products.

Microarray experiments comparing UA159 and JAM1 also revealed that fructose-PTS genes showed significantly altered levels in JAM1, confirming our earlier finding that EIIABMan regulates the fructose-PTS (1). Interestingly, the expression levels of SMU.674 and SMU.675, encoding the two central PTS enzymes HPr and EI, respectively, were about threefold higher in JAM1. It is well known that HPr directly participates in the classical CCR model proposed for low G+C gram-positive bacteria by forming a complex with CcpA and then binding to the cis-acting replication elements in the promoter regions of genes that are under CCR (6, 38). However, it appears that this model of CCR does not necessarily apply to S. mutans, since strains lacking CcpA do not show the alleviation of CCR of genes that are tightly linked to sequences of cis-acting replication elements (51). We suggest that EIIABMan may be a central regulator in CCR by sensing the availability of particular sugars or the availability of phosphoenolpyruvate and exerting its control by phosphorylation or direct interaction with potential targets as outlined above. Microarray analysis revealed that at least 10 functional categories had genes with altered expression in JAM1 (Fig. 5), providing additional evidence (1, 48) that the impact of EIIABMan on gene expression in S. mutans is extremely broad. It is likely that the effects observed could be a consequence of alterations in carbohydrate metabolism caused by the direct involvement of EIIABMan in the allosteric regulation of several proteins, including transcriptional regulators. At this point, it is clear that EIIABMan has a central role in controlling energy metabolism and PTS gene regulation and may act as an energy level sensor in the cell.

The complex process of competence development and DNA uptake involves a network of several genes. Many of these genes were previously reported to be involved in stress tolerance and biofilm formation (3, 13, 21, 34, 37). The process of competence is not only necessary for the achievement of genetic variability but also allows the use of extracellular DNA as an energy source (14). In Haemophilus influenzae, competence was demonstrated to be under direct nutritional control by a fructose-PTS, suggesting that cells take up DNA primarily to obtain nucleotides (31) and perhaps for energy generation. In the oral cavity, DNA, which comes from the host and the complex microbial communities living on the host tissues, is probably abundant. The observation that JAM1 has a reduced capacity to be transformed suggests that the involvement of EIIABMan in competence in S. mutans may not be directly related to genetic recombination, but rather it is required to balance the energy levels of the cell.

Interestingly, the gene encoding the histidine kinase of the covS/vicK two-component system was down-regulated 3.5-fold in JAM1 (Table 3). This two-component system has been shown to regulate the expression of the genes for the glucosyltransferases GtfB, -C, and -D, which convert sucrose to adhesive extracellular homopolymers of glucose as well as the gbpB gene, which encodes a major glucan binding protein, and the ftf gene, which codes for the enzyme that converts sucrose to extracellular homopolymers of fructose, fructans (40). Also, a strain lacking a functional vicK was demonstrated to form less biofilm and had reduced transformation efficiency (18, 40). So, it is possible that the impaired capacity of JAM1 to form biofilms and be transformed is in part also related to the down-regulation of vicK.

In E. coli, glycogen biosynthesis is controlled by the levels of glycolytic intermediates, including stimulation by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and inhibition by AMP, ADP, and orthophosphate (36), so that glycogen production is enhanced when carbohydrates are abundant and repressed when ATP levels decrease. In contrast, the levels of glycolytic intermediates did not appear to regulate glycogen anabolism in Bacillus stearothermophilus, indicating that there are alternative mechanisms in bacteria for the regulation of glycogen metabolism (45). In S. mutans UA130, the dlt genes are also responsible for the accumulation of intracellular storage polymers (IPS) (43). Mutations in enzyme I, the central PTS enzyme, caused altered transcript levels of dlt genes, suggesting that the PTS regulates the accumulation of IPS (43). As revealed by microarrays, glycogen biosynthesis genes had higher expression levels in JAM1, suggesting a role for EIIABMan in the negative regulation of glycogen anabolism. The sensing of exogenous sugars and the capacity to detect changes in carbohydrate flux through the glycolytic pathway may allow EIIABMan to act as a central regulator that balances IPS accumulation against catabolism.

Concluding remarks.

Our investigation revealed that the inactivation of the ptsG gene does not lead to major changes in sugar metabolism, biofilm formation, and competence. Building on our previous work with the EIIABMan porter, encoded by the manL gene, we demonstrated that EIIABMan regulates the lactose and cellobiose-PTS, and influences the process of competence and biofilm formation. We used microarray analysis to investigate the basis for the profound changes in phenotype observed in the EIIABMan mutant strain, revealing that at least 10 functional categories of genes showed alterations in expression in the ManL-deficient strain. Consistent with the central role of IIABMan in the regulation of the acquisition of essential energy sources and with the fact that S. mutans depends entirely on substrate-level phosphorylation for growth, the category of energy metabolism had the greatest number of genes with altered expression. In conclusion, we suggest that EIIABMan has a central regulatory role in the physiology and virulence of S. mutans by sensing the energy levels of the cell and directly regulating the activity of several regulatory proteins and PTS porters through allosteric interactions or phosphorelay or indirectly by influencing carbohydrate utilization. Efforts to dissect the mechanisms of EIIman-dependent regulation of gene expression are under way.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paulo H. Rodrigues, Maria R. L. Simionato, and Cecilia Lopez for their helpful guidance in microarray experiments. We also thank Ann Griswold, Jose Lemos, and Marcelle Nascimento for their valuable comments.

This work was supported by DE12236.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abranches, J., Y. Y. Chen, and R. A. Burne. 2003. Characterization of Streptococcus mutans strains deficient in EIIABMan of the sugar phosphotransferase system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4760-4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abranches, J., Y. Y. Chen, and R. A. Burne. 2004. Galactose metabolism by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6047-6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, S. J., J. A. Lemos, and R. A. Burne. 2005. Role of HtrA in growth and competence of Streptococcus mutans UA159. J. Bacteriol. 187:3028-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajdíc, D., W. M. McShan, R. E. McLaughlin, G. Savíc, J. Chang, M. B. Carson, C. Primeaux, R. Tian, S. Kenton, H. Jia, S. Lin, Y. Qian, S. Li, H. Zhu, F. Najar, H. Lai, J. White, B. A. Roe, and J. J. Ferretti. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14434-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asanuma, N., T. Yoshii, and T. Hino. 2004. Molecular characteristics of phosphoenolpyruvate: mannose phosphotransferase system in Streptococcus bovis. Curr. Microbiol. 49:4-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruckner, R., and F. Titgemeyer. 2002. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: choice of the carbon source and autoregulatory limitation of sugar utilization. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burne, R. A., R. G. Quivey, Jr., and R. E. Marquis. 1999. Physiologic homeostasis and stress responses in oral biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:441-460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Burne, R. A., K. Schilling, W. H. Bowen, and R. E. Yasbin. 1987. Expression, purification, and characterization of an exo-β-d-fructosidase of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 169:4507-4517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burne, R. A., Z. T. Wen, Y. Y. Chen, and J. E. Penders. 1999. Regulation of expression of the fructan hydrolase gene of Streptococcus mutans GS-5 by induction and carbon catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 181:2863-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Y. Y., T. H. Hall, and R. A. Burne. 1998. Streptococcus salivarius urease expression: involvement of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 165:117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochu, A., C. Vadeboncoeur, S. Moineau, and M. Frenette. 2003. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the phosphoenolpyruvate:glucose/mannose phosphotransferase system of Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5423-5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cote, C. K., and A. L. Honeyman. 2002. The transcriptional regulation of the Streptococcus mutans bgl regulon. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 17:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dagkessamanskaia, A., M. Moscoso, V. Henard, S. Guiral, K. Overweg, M. Reuter, B. Martin, J. Wells, and J. P. Claverys. 2004. Interconnection of competence, stress and CiaR regulons in Streptococcus pneumoniae: competence triggers stationary phase autolysis of ciaR mutant cells. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1071-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkel, S. E., and R. Kolter. 2001. DNA as a nutrient: novel role for bacterial competence gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 183:6288-6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamionka, A., S. Parche, H. Nothaft, J. Siepelmeyer, K. Jahreis, and F. Titgemeyer. 2002. The phosphotransferase system of Streptomyces coelicolor. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:2143-2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau, P. C., C. K. Sung, J. H. Lee, D. A. Morrison, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBlanc, D. J., V. L. Crow, L. N. Lee, and C. F. Garon. 1979. Influence of the lactose plasmid on the metabolism of galactose by Streptococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 137:878-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, S. F., G. D. Delaney, and M. Elkhateeb. 2004. A two-component covRS regulatory system regulates expression of fructosyltransferase and a novel extracellular carbohydrate in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 72:3968-3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemos, J. A., J. Abranches, and R. A. Burne. 2005. Responses of cariogenic streptococci to environmental stresses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 7:95-107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemos, J. A., T. A. Brown, Jr., and R. A. Burne. 2004. Effects of RelA on key virulence properties of planktonic and biofilm populations of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 72:1431-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemos, J. A., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Regulation and physiological significance of ClpC and ClpP in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 184:6357-6366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lengeler, J. W., K. Jahreis, and U. F. Wehmeier. 1994. Enzymes II of the phosphoenol pyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase systems: their structure and function in carbohydrate transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1188:1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, Y. H., P. C. Lau, J. H. Lee, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2001. Natural genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans growing in biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 183:897-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, Y. H., N. Tang, M. B. Aspiras, P. C. Lau, J. H. Lee, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. A quorum-sensing signaling system essential for genetic competence in Streptococcus mutans is involved in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 184:2699-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberman, E. S., and A. S. Bleiweis. 1984. Glucose phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system of Streptococcus mutans GS5 studied by using cell-free extracts. Infect. Immun. 44:486-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman, E. S., and A. S. Bleiweis. 1984. Role of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent glucose phosphotransferase system of Streptococcus mutans GS5 in the regulation of lactose uptake. Infect. Immun. 43:536-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberman, E. S., and A. S. Bleiweis. 1984. Transport of glucose and mannose by a common phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system in Streptococcus mutans GS5. Infect. Immun. 43:1106-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loo, C. Y., K. Mitrakul, I. B. Voss, C. V. Hughes, and N. Ganeshkumar. 2003. Involvement of an inducible fructose phosphotransferase operon in Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 185:6241-6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lortie, L. A., M. Pelletier, C. Vadeboncoeur, and M. Frenette. 2000. The gene encoding IIABLMan in Streptococcus salivarius is part of a tetracistronic operon encoding a phosphoenolpyruvate: mannose/glucose phosphotransferase system. Microbiology 146:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lun, S., and P. J. Willson. 2005. Putative mannose-specific phosphotransferase system component IID represses expression of suilysin in serotype 2 Streptococcus suis. Vet. Microbiol. 105:169-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macfadyen, L. P., I. R. Dorocicz, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, Jr., and R. J. Redfield. 1996. Regulation of competence development and sugar utilization in Haemophilus influenzae Rd by a phosphoenolpyruvate:fructose phosphotransferase system. Mol. Microbiol. 21:941-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Farrell, P. H. 1975. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4007-4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen, F. C., and A. A. Scheie. 2000. Genetic transformation in Streptococcus mutans requires a peptide secretion-like apparatus. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 15:329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen, F. C., L. Tao, and A. A. Scheie. 2005. DNA binding-uptake system: a link between cell-to-cell communication and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 187:4392-4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Postma, P. W., J. W. Lengeler, and G. R. Jacobson. 1993. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:543-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Preiss, J., and T. Romeo. 1994. Molecular biology and regulatory aspects of glycogen biosynthesis in bacteria. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 47:299-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathsam, C., R. E. Eaton, C. L. Simpson, G. V. Browne, T. Berg, D. W. Harty, and N. A. Jacques. 2005. Up-regulation of competence- but not stress-responsive proteins accompanies an altered metabolic phenotype in Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Microbiology 151:1823-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saier, M. H., Jr. 1996. Regulatory interactions controlling carbon metabolism: an overview. Res. Microbiol. 147:439-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saier, M. H., Jr., and I. T. Paulsen. 1999. Paralogous genes encoding transport proteins in microbial genomes. Res. Microbiol. 150:689-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senadheera, M. D., B. Guggenheim, G. A. Spatafora, Y. C. Huang, J. Choi, D. C. Hung, J. S. Treglown, S. D. Goodman, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2005. A VicRK signal transduction system in Streptococcus mutans affects gtfBCD, gbpB, and ftf expression, biofilm formation, and genetic competence development. J. Bacteriol. 187:4064-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw, W. V., L. C. Packman, B. D. Burleigh, A. Dell, H. R. Morris, and B. S. Hartley. 1979. Primary structure of a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase specified by R plasmids. Nature 282:870-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sondej, M., A. B. Weinglass, A. Peterkofsky, and H. R. Kaback. 2002. Binding of enzyme IIAGlc, a component of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system, to the Escherichia coli lactose permease. Biochemistry 41:5556-5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spatafora, G. A., M. Sheets, R. June, D. Luyimbazi, K. Howard, R. Hulbert, D. Barnard, M. el Janne, and M. C. Hudson. 1999. Regulated expression of the Streptococcus mutans dlt genes correlates with intracellular polysaccharide accumulation. J. Bacteriol. 181:2363-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutrina, S. L., P. Reddy, M. H. Saier, Jr., and J. Reizer. 1990. The glucose permease of Bacillus subtilis is a single polypeptide chain that functions to energize the sucrose permease. J. Biol. Chem. 265:18581-18589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takata, H., T. Takaha, S. Okada, M. Takagi, and T. Imanaka. 1997. Characterization of a gene cluster for glycogen biosynthesis and a heterotetrameric ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 179:4689-4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueguchi, C., N. Misonou, and T. Mizuno. 2001. Negative control of rpoS expression by phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:520-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vadeboncoeur, C., M. Frenette, and L. A. Lortie. 2000. Regulation of the pts operon in low G+C gram-positive bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:483-490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vadeboncoeur, C., and M. Pelletier. 1997. The phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system of oral streptococci and its role in the control of sugar metabolism. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 19:187-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weaver, C. A., Y. Y. Chen, and R. A. Burne. 2000. Inactivation of the ptsI gene encoding enzyme I of the sugar phosphotransferase system of Streptococcus salivarius: effects on growth and urease expression. Microbiology 146:1179-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1196-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Analysis of cis- and trans-acting factors involved in regulation of the Streptococcus mutans fructanase gene (fruA). J. Bacteriol. 184:126-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin, J. L., N. A. Shackel, A. Zekry, P. H. McGuinness, C. Richards, K. V. Putten, G. W. McCaughan, J. M. Eris, and G. A. Bishop. 2001. Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for measurement of cytokine and growth factor mRNA expression with fluorogenic probes or SYBR green I. Immunol. Cell Biol. 79:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]