Abstract

In Comamonas testosteroni strain BR6020, metabolism of isovanillate (iVan; 3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzoate), vanillate (Van; 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate), and veratrate (Ver; 3,4-dimethoxybenzoate) proceeds via protocatechuate (Pca; 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate). A 13.4-kb locus coding for the catabolic enzymes that channel the three substrates to Pca was cloned. O demethylation is mediated by the phthalate family oxygenases IvaA (converts iVan to Pca and Ver to Van) and VanA (converts Van to Pca and Ver to iVan). Reducing equivalents from NAD(P)H are transferred to the oxygenases by the class IA oxidoreductase IvaB. Studies using whole cells, cell extracts, and reverse transcriptase PCR showed that degradative activity and expression of vanA, ivaA, and ivaB are inducible. In succinate- and Pca-grown cells, there is negligible degradative activity towards Van, Ver, and iVan and little to no expression of vanA, ivaA, and ivaB. Growth on Van or Ver results in production of oxygenases with activity towards Van, Ver, and iVan and expression of vanA, ivaA, and ivaB. With iVan-grown cultures, ivaA and ivaB are expressed, and in assays with whole cells, production of the iVan oxygenase is observed, but there is little activity towards Van or Ver. In cell extracts, though, Ver metabolism is observed, which suggests that the system mediating iVan uptake in whole cells does not mediate Ver uptake.

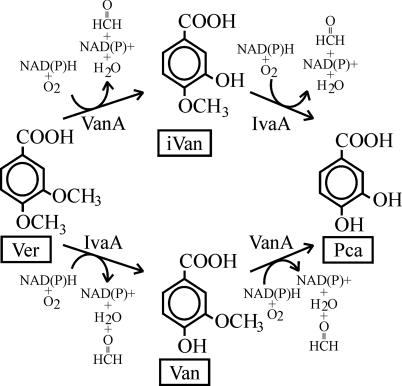

Lignin is a complex aromatic polymer which provides strength and rigidity to plant cells. It is one of the most abundant forms of organic matter on earth, and its breakdown is integral to the carbon cycle. Aerobic biodegradation of lignin is mediated by various microorganisms, such as ligninolytic fungi (which depolymerize lignin) and bacteria (which catabolize the simpler aromatic subunits that are released). Model substrates used to study aerobic biodegradation of lignin-derived methoxylated monocyclic aromatic compounds by prokaryotes include vanillate (Van; 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate), isovanillate (iVan; 3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzoate), and veratrate (Ver; 3,4-dimethoxybenzoate; Fig. 1) (14, 22).

FIG. 1.

Biodegradation of isovanillate, vanillate, and veratrate in C. testosteroni strain BR6020 is initiated by IvaA and VanA, oxygenases that mediate, respectively, 4-O demethylation of iVan and Ver and 3-O demethylation of Van and Ver. Reducing equivalents from NAD(P)H are transferred to the oxygenases by IvaB (not shown). The three aromatic compounds are channelled towards protocatechuate, which is metabolized by the 4,5-extradiol (meta) ring fission pathway (30).

Different pathways for aerobic catabolism of Van in bacteria have been reported. In various Pseudomonas spp. and in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1, metabolism is initiated by oxidative O demethylation, resulting in protocatechuate (Pca), formaldehyde, and H2O. The reaction is mediated by NAD(P)H-requiring two-component enzymes composed of an oxygenase and oxidoreductase that are encoded by vanA and vanB and closely related homologues, respectively (7-10, 12, 29, 33, 35, 39). In Sphingomonas paucimobilis strain SYK-6, Van is also O demethylated to Pca, but it is a nonoxidative reaction mediated by a tetrahydrofolate-requiring enzyme encoded by ligM (1). Other pathways for Van catabolism have also been described, such as the one in Acinetobacter iwoffi, which hydroxylates Van in an NADPH-dependent reaction at position 5, resulting in 3-O-methylgallate (36); Pseudomonas fluorescens, which oxidatively decarboxylates Van in an NAD(P)H-dependent reaction, resulting in 2-methoxyhydroquinone and CO2 (18); and in Bacillus megaterium and various Streptomyces spp., which nonoxidatively decarboxylate Van, resulting in 2-methoxyphenol (guaiacol) and CO2 (2, 11, 16, 27). For Streptomyces sp. strain D7, the decarboxylase is encoded by vdcB (11). In contrast to that of Van, the aerobic catabolism of iVan and Ver has been studied in fewer bacteria and in less detail. In various Streptomyces and Nocardia spp., Ver is oxidatively O demethylated to a mixture of iVan and Van. With Nocardia spp., iVan and Van are then metabolized via Pca (14, 15, 24). No genes coding for iVan- and Ver-metabolizing enzymes have yet been described.

Comamonas (formerly Pseudomonas) testosteroni is recognized for its ability to degrade various synthetic and naturally occurring mono- and polycylic aromatic substrates (30). We previously showed that in C. testosteroni strain BR6020, Van, iVan, and Ver are channelled towards Pca, which is then metabolized by the pmd-encoded extradiol ring fission pathway (30). On the basis of studies with C. testosteroni strain NCIB8893, initial metabolism of Van and Ver in this bacterium proceeds via oxidative O demethylation and appears to be mediated by a VanAB-like enzyme or enzymes (8, 32). However, nothing is known regarding the genetics of Van and Ver metabolism in C. testosteroni, nor is there any information on iVan metabolism. In this study, we report on the biochemical and genetic characterization of the van-iva locus of C. testosteroni strain BR6020 encoding the enzymes for the initial metabolism of iVan, Van, and Ver. It is homologous to the widespread vanAB system for catabolism of Van, but it is novel in both its detailed biochemistry and genetic parsimony.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. C. testosteroni strain BR6020 was grown at 30°C on minimal medium A (40) supplemented with 10 mM succinate or 4 to 12 mM iVan, Van, Ver, or Pca. Aromatic compounds were added to media after autoclaving from filter-sterilized 400 mM stock solutions. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 30 to 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium (1% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.5% [wt/vol] NaCl) supplemented with ampicillin (250 mg liter−1), kanamycin (40 mg liter−1), or isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM), as required. All chemicals and antibiotics were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotye or genotypea | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| C. testosteroni BR6020 | Plasmid-free derivative of C. testosteroni BR60 (pBRC40). Formerly classified as an Alcaligenes species. Grows on benzoate and various other benzoate-based compounds | 30, 31, 41 |

| E. coli JM109 | α-lacZ-complementing strain. Used as host for pLIB-based clones | 42 |

| E. coli TOP10F′ | α-lacZ-complementing strain. Used as host for derivatives of pCR2.1-TOPO during cloning of PCR-generated products | Invitrogen |

| E. coli M15 | Host for pREP4- and pQE30-based expression vectors | Qiagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Ampr Kmr, α-lacZ/MCS. Cloning vector for PCR-generated products | Invitrogen |

| pQE30 | Ampr. IPTG-inducible expression vector. Adds a six-histidine affinity tag to the N termini of proteins cloned into the MCS | Qiagen |

| pREP4 | Kmr LacIq. Controls expression of genes cloned into pQE30 | Qiagen |

| pLIB2F10 | Ampr. Harbors portion of van-iva locus spanning nt 1 to nt 6063 | This study |

| pLIB23D3 | Ampr. Harbors portion of van-iva locus spanning nt 4691 to nt 10335. Positive for conversion of iVan to Pca | This study |

| pLIB1F2 | Ampr. Harbors portion of van-iva locus spanning nt 8790 to nt 13435 | This study |

| pLIB2F1-23D3 | Ampr. EcoRI fragment from pLIB2F10 (spanning nt 469 to nt 6044 of van-iva locus) cloned into EcoRI-digested pLIB23D3 so that the fragment is in the correct orientation, relative to the gene order that occurs naturally in the van-iva locus. Positive for conversion of Van, iVan, and Ver to Pca | This study |

| pCR2.1-vanA4 | Ampr Kmr. Amplicon generated with primer pair VanA-FEx plus VanA-REx cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO | This study |

| pCR2.1-ivaA5 | Ampr Kmr. Amplicon generated with primer pair IvaA-FEx plus IvaA-REx cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO | This study |

| pCR2.1-ivaB4 | Ampr Kmr. Amplicon generated with primer pair IvaB-FEx plus IvaB-REx cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO | This study |

| pQE30-vanA1 | Ampr. BamHI/SacI fragment from pCR2.1-vanA4 subcloned into pQE30 digested with BamHI/SacI | This study |

| pQE30-ivaA3 | Ampr. BamHI/XhoI fragment from pCR2.1-ivaA5 subcloned into pQE30 digested with BamHI/SalI | This study |

| pQE30-ivaB1 | Ampr. BamHI/XhoI fragment from pCR2.1-ivaB4 subcloned into pQE30 digested with BamHI/SalI | This study |

Abbreviations: α-lacZ, codes for the α fragment of LacZ; IPTG, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; MCS, multiple cloning site; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

Analytical techniques used to study metabolism of iVan, Van, and Ver.

Oxygenase activity by whole cells of C. testosteroni BR6020, cell extracts of BR6020, and affinity-purified His-tagged enzymes obtained from E. coli (see below) were measured by oxygen polarography using a Clarke-type electrode (Rank Bros Ltd., Bottisham, United Kingdom) as described elsewhere (34). All activity measurements were corrected for endogenous O2 uptake. Reductase activity by His-tagged IvaB (see below) was measured as NAD(P)H-dependent reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP), as described elsewhere (23). Cell extracts were prepared by passage through a French pressure cell or by sonication, followed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g to 70,000 × g. Protein content was determined for whole cells using a Lowry-type assay (21) and for cell extracts and purified enzymes using the Bradford reagent (6). Aromatic compounds were identified by cochromatography with authentic chemicals via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using as a solvent methanol and phosphate-buffered water (0.01 M KPO4, pH 2.2). Samples were first acidified with H3PO4 (final concentration, 0.1 M) and then analyzed on a Varian Prostar apparatus with (i) a Nucleosil C18 reversed-phase 125- by 3-mm column at 25°C using a gradient protocol (25% methanol for the first 2 min and then raising methanol to 80% over a 9-min period and holding at 80% methanol for 5 min), or (ii) a Polaris 5 C18-A reversed-phase 250- by 4.6-mm column cooled in an ice-water slurry using an isocratic protocol (60% methanol). The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and aromatic compounds were detected at 220 nm. Typical retention times for Pca, Van, iVan, and Ver were, respectively, 4.2, 8.3, 8.8, and 11.7 min with the Nucleosil column and 7.8, 9.2, 8.9, and 10.8 min with the Polaris column.

Cloning the van-iva locus.

A plasmid library of total DNA from strain BR6020 (∼2,300 clones) (30) was screened for clones capable of generating Pca from iVan, Van, or Ver using the colorimetric method developed by Parke for detection of vicinal diols (26) with minor modifications (30). No clones were positive for Pca production from Ver or Van, but one clone was positive for Pca production from iVan (pLIB23D3). Both strands of the insert were sequenced by primer walking after an initial run with vector-specific primers M13F and M13R (GATC Biotech AG, Konstanz, Germany). The upstream end of the insert in pLIB23D3 harbored an open reading frame (ORF) coding for the C terminus of a VanA-like oxygenase, indicating that genes putatively involved in Van and/or Ver catabolism were adjacent to the genes coding for iVan-metabolizing enzymes. To identify DNA upstream of the insert in pLIB23D3, the library was screened by PCR using primer pair VanA-F1 plus VanA-R1 (described below), and three clones were identified. The clone harboring the greatest amount of novel DNA (pLIB2F10) was sequenced. The downstream end of the insert in pLIB23D3 harbored an ORF coding for the N terminus of a gene product (ORF dubbed ivaC) (see below regarding nomenclature), and to complete the latter's sequence, the library was screened by PCR with primer pair IvaC-F1 plus IvaC-R1 (described below), and one clone was identified (pLIB1F2). Both strands of the inserts of pLIB2F10 and pLIB1F2 were sequenced by a random transposon insertion method (QIAGEN Genomics Inc. Sequencing Services, Washington). All DNA sequences were determined by the chain-terminating dideoxy method on ABI Prism automated sequencers. To determine whether the vanA-like ORF coded for a functional enzyme, pLIB2F10-23D3 (Table 1) was analyzed using the vicinal diol assay (see above), and Pca was produced from Van, Ver, and iVan. ORFs uncovered in pLIB23D3 (except for vanA) were dubbed iva because the functional assay used to identify this clone indicated that the insert harbored the iVan oxygenase. ORFs in flanking DNA were dubbed van if they showed homology to genes previously shown to be involved in Van metabolism or ctb (for C. testosteroni BR6020) if their function remains to be established.

Overproduction and purification of His-tagged VanA, IvaA, and IvaB.

Genes coding for VanA, IvaA, and IvaB were PCR amplified as described below using purified pLIB2F10-23D3 (Table 1) as the template and primer pairs VanA-FEx plus VanA-REx (ggatccGCTAGCAACCATCAGGAACAAGCC and gtcgacTCAAGCCAGCGCCGCAACGCCCGA, respectively), IvaA-FEx plus IvaA-REx (ggatccGCTAGCAACCAGATTTCTCACACC and ctcgagCTAGGCCACCGCCTGCGAGGCTTG, respectively), and IvaB-FEx plus IvaB-REx (ggatccGCTAGCAAGACTGAAACCACGTTC and ctcgagTCACAGATCCAGCACCAGGCG, respectively). The FEx series of primers are complementary to the N-terminal region-coding portions of the indicated genes. These primers lack the native start codon of the respective genes but harbor an engineered BamHI site (lowercase nucleotides), which in pQE30 places genes downstream of and in frame with DNA coding for the N-terminal affinity tag MRGSH6GS. The REx series of primers are complementary to the C-terminal region-coding portion of the indicated genes up to and including the native stop codon (underlined nucleotides) and harbor an engineered SacI site (VanA-REx) or XhoI site (IvaA-REx and IvaB-REx) (lowercase nucleotides). Amplicons were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen), sequenced using vector-specific primers M13F and M13R to confirm that no mutations had been introduced during PCR (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea) and then subcloned into pQE30 as described in Table 1. Proteins were overproduced and affinity purified with Ni-nitriloacetic acid agarose (Ni-NTA; QIAGEN, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) per the manufacturer's recommendations, retained in elution buffer, and held on ice. Under these conditions, the oxygenases showed no loss of activity for at least 6 h but lost all activity after ∼24 h. IvaB, though, could be stored at −20°C in 50% (vol/vol) glycerol for at least 2 months with only a 10 to 20% loss of activity.

RT-PCR analyses.

Qualitative analyses of expression patterns of select genes in the van-iva locus were by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) as described elsewhere (38). In brief, 500 ng of DNA-free total RNA from mid-log-phase cultures of C. testosteroni BR6020 grown on iVan, Van, Ver, Pca, or succinate were reverse transcribed using primer IvaB-R1 or IvaC-R1 (described below). Aliquots of cDNA (1 to 2 μl) were then analyzed by PCR (initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 35 s [denaturation], 60°C for 35 s [primer annealing], and 72°C for 1 min [extension]; ending with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min), and 4 μl of each PCR mixture was analyzed by agarose electrophoresis. The primer pairs used to target different genes of the van-iva locus (amplicon sizes and primer sequences in parentheses) were VanA-F1 plus VanA-R1 (420 bp; GCCGATGACGTGCCTGTGGAC and CGCCGCAACGCCCGACTC, respectively), IvaR-F1 plus IvaR-R1 (342 bp; GCTTGCTCGCCGGCTTCAGTGCT and GACGCCGGTTCAATACGCCATCCT, respectively), IvaK-F1 plus IvaK-R1 (1,172 bp; GACCAGCGGCCCATGACGACCTTC and GCCACCAGCGGCGACACAATC, respectively), IvaA-F1 plus IvaA-R1 (383 bp; TCCGACCAAGGCCTGCGTGAAGT and AGCGGTCGATGCGGCCCTGAAAAG, respectively), IvaB-F1 plus IvaB-R1 (471 bp; ATCGAGACTGCGCAATGGGCTGACAA and GCGCGAGCAGCAGGGCAGGAACT, respectively), and IvaC-F1+IvaC-R1 (312 bp; CCATGGGTGCGGGCTACGAGAAC and CGCGCGGCTTGCGGTTGTGATA, respectively). Negative controls were samples that did not include a primer during reverse transcription and samples to which no reverse transcriptase was added. RNA from two independently grown cultures was analyzed, and the results were the same.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence described in this article has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AY705372.

RESULTS

Metabolism of iVan, Van, and Ver by whole cells.

With whole cells of C. testosteroni strain BR6020, specific activity towards iVan, Van, and Ver varied by ≤10% from early log to early stationary phase with cultures growing on the respective substrates, indicating no growth-phase dependence for expression of iVan, Van, and Ver oxygenases. Detailed studies investigating induction patterns of the oxygenases were conducted with mid- to late-log-phase cultures, and the results are summarized in Table 2. Growth on iVan induced maximal activity towards iVan and low activity towards Van or Ver (∼10% of maximal activity). In contrast, growth on Van and Ver induced maximal or near-maximal activity towards Van, Ver, and iVan. Growth on iVan, Van, and Ver induced comparable levels of activity towards Pca and succinate. Last, growth on Pca and succinate induced little to no activity towards iVan, Van, and Ver (≤3% of maximum), indicating that production of the oxygenases for these substrates is inducible.

TABLE 2.

Oxygen consumption by whole cells of C. testosteroni strain BR6020 towards the indicated carbon sources

| Growth substrate | O2 consumption rate (mkat/kg of protein) when exposed to:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iVan | Van | Ver | Pca | Succinate | |

| iVan | 12.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 20.4 | 2.1 |

| Van | 12.0 | 11.7 | 8.3 | 22.0 | 2.0 |

| Ver | 10.9 | 10.6 | 7.7 | 21.8 | 2.3 |

| Pca | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 15.9 | 2.4 |

| Succinate | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 5.7 |

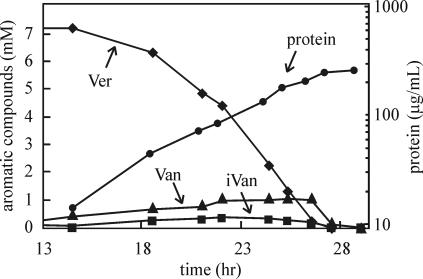

For cells growing on iVan and Van, no aromatic compounds were detected in the culture medium. However, with Ver-growing cells, Van and iVan at a molar ratio of ∼3:1 were detected in the medium during the exponential phase of growth. Van and iVan were then consumed once Ver was completely used up and cells entered early stationary phase (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

C. testosteroni strain BR6020 growing at the expense of Ver releases Van and iVan into the culture medium. Growth was measured as the protein concentration.

Metabolism of iVan, Van, and Ver by cell extracts.

With cell extracts from iVan-, Van-, and Ver-grown strain BR6020, oxygenase activity towards iVan, Van, and Ver was dependent on the addition of NAD(P)H. Specific activity towards these substrates was ∼10 to 15% of those observed with whole cells, while specific activity towards Pca was the same as with whole cells. Despite the lower activity levels, the induction patterns toward iVan, Van, and Ver with extracts from iVan-, Van-, and Ver-grown cells were the same as those observed with whole cells (see above and Table 2), except that in extracts from iVan-grown cells, Ver induced higher activity than in whole cells (relative to maximal levels observed with iVan, ∼40% instead of ∼9%).

To confirm that O2-consuming activity induced by iVan, Van, and Ver in cell extracts corresponded with modification of the starting substrates, reactions were analyzed by HPLC following cessation of all activity. If limiting amounts of iVan, Van, and Ver were used relative to the amount of O2 (final concentration of the substrates was 0.04 mM versus 0.24 mM O2), no iVan, Van, and Ver could be detected when using cell extracts from Van- or Ver-grown cells. Similarly, no iVan was detected when using cell extracts from iVan-grown cells. If excess Ver was added to extracts from Van- or Ver-grown cells, Van and iVan were detected. If excess Ver was added to extracts from iVan-grown cells, Van was detected. Pca was not detected in any of these assays, likely because any Pca that was generated was consumed immediately by the highly active Pca oxygenase present in the extracts (described above). The stoichiometry of oxygen consumption was 2 mol of O2 per mol of iVan or Van, 3 mol O2 per mol Ver, and 1 mol O2 per mol Pca. This indicates that with iVan and Van, 1 mol is used during oxidative O demethylation and 1 mol is used for Pca ring cleavage. With Ver, 2 mol is used by O demethylation and 1 mol is used for Pca ring cleavage.

Identification of the van-iva locus.

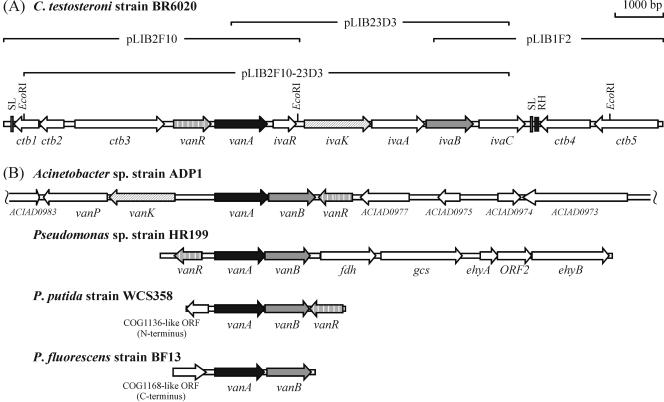

A 13,435-bp region from strain BR6020 coding for enzymes capable of converting iVan, Van, and Ver to Pca was cloned (see Materials and Methods), and a total of 12 ORFs were identified. The physical organization of the ORFs is shown in Fig. 3A, and the amino acid lengths and molecular weights of the putative products from this region are listed in Table 3, as are homologues in the GenBank, Pfam, and COG databases. Obvious candidates for the oxygenases were VanA and IvaA, which show identity to VanAADP1 and TsaM, respectively (Table 3), two members of the phthalate family of aromatic oxygenases (19). Likewise, an obvious candidate for the oxidoreductase was IvaB, which shows homology to VanBADP1 (Table 3), a member of class IA of the aromatic oxidoreductases (5).

FIG. 3.

(A) Physical map of the 13.4-kb region from C. testosteroni strain BR6020 harboring the van-iva locus, which codes for VanA (3-O-demethylase for Van and Ver), IvaA (4-O-demethylase for iVan and Ver), and IvaB (oxidoreductase that transfers reducing equivalents from NAD(P)H to VanA and IvaA). Putative functions of the other gene products are described in the text. Also indicated on the map are the positions of EcoRI restriction sites (used to construct pLIB2F10-23D3); two potential stem-loop structures (SL); and a section which is ∼90% identical to the intergenic region between pmdF and pmdD (RH). The latter two are genes of the Pca meta ring fission pathway of BR6020 (30). Indicated above the map are regions present in clones described in this study. (B) Physical maps of other loci coding for VanAB-like enzymes. Bacteria from which the genes were isolated are shown above each locus, and ORFs coding for proteins that are functionally identical to or show sequence similarity to products from the van-iva locus of BR6020 are shaded identically. The locus from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 was originally described in reference 35 (GenBank accession number AF009672) and reannotated following complete sequencing of the genome (3) (CR543861). For the sake of brevity, ORFs annotated as coding for “doubtful proteins” are not shown. The locus from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 was originally described in references 29 (Y11521) and 28 (AJ243941), and the two sequences were assembled into one contiguous region for this figure. The locus from Pseudomonas putida strain WCS358 was described in reference 39 (Y14759). The locus from P. fluorescens strain BF13 was described in reference 12 (AJ245887). Note that the vanR-like ORFs in the loci from strains HR199 and WCS358, the COG1136-like ORF in the locus from strain WCS358, and the COG1168-like ORF in the locus from strain BF13 were not originally described in the respective publications or GenBank entries and are based on BLAST analyses conducted when creating this figure. The prototypic VanAB-encoding locus from Pseudomonas sp. strain ATCC 19151 (7) is similar to loci displayed in panel B with respect to arrangement of vanAB. However, it is not shown for the sake of brevity.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of products from the van-iva locus to entries in the GenBank, Pfam, or COG databasea

| Product | Sizeb (aa) | MMb (kDa) | GenBank, Pfam, or COG entryc | Description of homologued |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctb1 | 170 | 18.6 | Pfam03061 | Thioesterase superfamily |

| Ctb2 | 166 | 18.3 | Rv3701c (33) NP_218218 | Hypothetical protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv (13) |

| Ctb3 | 609 | 107.3 | COG5265 | Group ATM1 of the ATP-binding cassette transporters. Permease and ATPase components. Involved in Fe-S cluster assembly |

| VanR | 254 | 27.9 | VanR (38) AAC27105 | Repressor of vanAB in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (25) |

| VanA | 358 | 40.1 | VanA (72) AF009672 | Van monooxygenase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (35) |

| IvaR | 159 | 17.9 | Pfam01047 | MarR-like transcriptional regulator |

| IvaK | 451 | 47.3 | VanK (46) YP_045696 | Mediates uptake of Pca and Van in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (17) |

| IvaA | 359 | 40.3 | TsaM (37) AF311437 | 4-Toluene sulfonate/carboxylate methyl monooxygenase from C. testosteroni strain T-2 (20) |

| IvaB | 322 | 35.1 | VanB (55) AF009672 | Oxidoreductase for VanA in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (35) |

| IvaC | 313 | 32.7 | Pfam00389 (aa 48 and 97) | Catalytic domain of d-isomer-specific dehydrogenases for 2-hydroxy acids |

| Pfam02826 (aa 106 to 280) | NAD-binding domain of d-isomer-specific dehydrogenases for 2-hydroxy acids | |||

| Ctb4 | 345 | 37.2 | COG1638 | DctP, the periplasmic component of the tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP)-type C4-dicarboxylate transport system involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| Ctb5 | 432 | 45.2 | COG1593 | DctQ, large permease component of the TRAP-type C4-dicarboxylate transport system involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

Functionally characterized GenBank homologues are shown for VanA, IvaA, and IvaB because the latter three are the focus of this study, and for VanR and IvaK because the latter show identity to proteins known to be involved in Van metabolism. Otherwise, homologues in the Pfam (Protein Family) database (4) or COG database (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) of proteins (37) are shown, except for Ctb2, which is not described in the latter two databases.

The size (in amino acids [aa]) and molecular mass (MM) (in kilodaltons) of the products are based on a conceptual translation of the genes.

For GenBank homologues, the percent identity is shown in parentheses. During analyses, more than one homologue in the Pfam or COG database was often uncovered. For the sake of brevity, only the entry with the lowest E value (i.e., highest significant match) is listed. E values were ≤4e−8, except for Ctb2 (E = 0.1).

Numbers in parentheses are references.

In addition to the ORFs, potential stem-loop structures were identified downstream of ctb1 and ivaC (potentially transcriptional terminators), and a region downstream of ctb4 (between nucleotides [nt] 10814 and 10921, the extreme upstream end of the locus having been designated nt 1) was 90% identical to intergenic regions in various proteobacteria, most notably a section between pmdF and pmdD (GenBank accession number AF305325). These genes code for Pca meta ring fission pathway enzymes in strain BR6020 (30). However, the significance of this similarity is not known.

Functional characterization of VanA, IvaA, and IvaB.

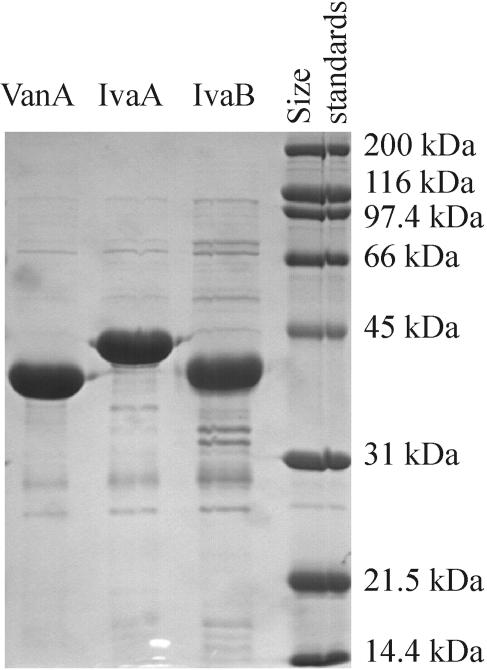

To confirm that VanA and IvaA are oxygenases and that IvaB is an oxidoreductase, the enzymes were N-terminally His tagged, overproduced in E. coli, and affinity purified to near-homogeneity (Fig. 4). For unknown reasons, the observed molecular masses of tagged IvaA and IvaB were slightly higher than the predicted values (for IvaA, 42.9 versus 41.7 kDa; for IvaB, 39.5 versus 36.5 kDa), while the observed molecular mass of tagged VanA was slightly lower than the predicted value (38.6 versus 41.5 kDa). Assays with the artificial electron acceptor DCPIP indicated that IvaB was an NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase. Analyses by oxygen polarography (results summarized in Table 4) and HPLC showed that VanA and IvaB enzymes mediate 3-O demethylation of Van and Ver, resulting in Pca and iVan, respectively, while IvaA and IvaB enzymes mediate 4-O demethylation of iVan and Ver, resulting in Pca and Van, respectively. Enzyme activity was dependent on NADH, although equally high activity was observed with NADPH (data not shown). No oxygenase activity was observed if one of the enzyme subunits was excluded from the assay. Activity levels towards Van by VanA plus IvaB and towards iVan by IvaA plus IvaB were similar. In contrast, activity levels towards Ver by VanA plus IvaB and IvaA plus IvaB differed markedly; relative to activity observed with Van, VanA plus IvaB exhibited 5.7 times less activity towards Ver, while with IvaA plus IvaB, activity towards Ver was 2.3 times higher than with iVan. Last, iVan and Pca added to VanA plus IvaB and Van or Pca added to IvaA plus IvaB induced low levels of activity (≤10% of those observed with Van or iVan, respectively), but HPLC analyses showed that the compounds were not modified, suggesting these low levels of activity represent substrate-induced uncoupling of oxygenase activity.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of affinity-purified, N-terminally His-tagged VanA, IvaA, and IvaB by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Ten micrograms of protein was loaded per lane, and molecular size standards (size indicated to the left) are shown for reference purposes.

TABLE 4.

Rates of oxygen consumption by the indicated enzyme combination

| Enzyme combination | Rate (mkat/kg of protein) of oxygen consumption induced bya:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van | iVan | Ver | Pca | |

| VanA + IvaBb | 2.5 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.12 |

| IvaA + IvaB | 0.24 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 0.10 |

Assays were performed with NADH. Similar results were obtained with NADPH (data not shown).

The molar ratio of oxygenase to IvaB in these assays ranged from 5:1 to 10:1.

Expression of vanA and ivaAB.

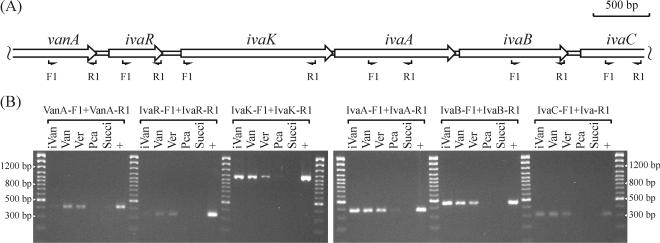

Expression patterns of vanA and ivaAB in strain BR6020 under different growth condition were examined by RT-PCR. Analyses were confined to the region from vanA to ivaC (Fig. 5A), since this region codes for VanA, IvaA, and IvaB, the focus of this study. Results with IvaC-R1 as the RT primer are shown in Fig. 5B. With cultures grown on iVan, the region from ivaK to ivaC was expressed. With cultures grown on Van or Ver, the region from vanA to ivaC was expressed. With cultures grown on Pca or succinate, no transcripts harboring vanA, ivaR, ivaK, ivaA, ivaB, or ivaC were detected, or a very faint amplicon was observed (e.g., RNA from Pca-grown cultures analyzed with primer pairs IvaR-F1 plus IvaR-R1 and IvaA-F1 plus IvaA-R1), indicating little to no expression of these genes under these growth conditions. Similar results were obtained using IvaB-R1 as the RT primer, except that ivaC was not detected. No amplicons were generated following PCR analyses of the controls (RT-free reactions and RT reactions which lacked a primer).

FIG. 5.

Expression patterns of select van-iva genes as determined by RT-PCR. (A) Physical map of the region analyzed and relative positions of the various primers used. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis results of PCR analyses of RT reactions. IvaC-R1 was the RT primer. Indicated above the horizontal brackets are the primer pairs used for PCRs, and over each lane the carbon source used to grow strain BR6020 prior to total RNA extraction (Succi, succinate). Lanes marked + show results from PCRs of the positive controls (whole cells of BR6020). Indicated to the left and right of the gels are the lengths (in base pairs) of selected size standards from the 100-bp ladder.

DISCUSSION

Functional characterization of IvaA, VanA, and IvaB and expression patterns of the catabolic genes.

In this study, we show that initial metabolism of iVan, Van, and Ver in C. testosteroni strain BR6020 is mediated by the oxygenases VanA (O demethylates Van to Pca and Ver to iVan) and IvaA (O demethylates iVan to Pca and Ver to Van) (degradation pathway summarized in Fig. 1). VanA is approximately six times less active towards Ver than to Van. In contrast, IvaA is ca. two times more active towards Ver than to iVan (Table 4). This suggests that Ver might be the “true” substrate for IvaA. Reducing equivalents from NAD(P)H are transferred to the oxygenases by IvaB. To our knowledge, the system described here is the first example of two oxygenases sharing one oxidoreductase.

The genes for VanA, IvaA, and IvaB are encoded at one locus (Fig. 3A). Growth on iVan induces expression of the region from ivaK to ivaC, while growth on Van and Ver induces expression of a longer region spanning vanA to ivaC (Fig. 5B). These results indicate the presence of at least two independent promoters, one of which may be between ivaR and ivaK. The gene expression patterns elucidated by RT-PCR explain (i) the very low levels of oxygenase activity that are observed towards Van with whole cells and cell extracts from iVan-grown cultures and (ii) the high oxygenase activity levels towards iVan and Ver that are observed with whole cells and cell extracts from Van-grown cultures (Table 2 and Results). However, we are unsure why, with whole cells and cell extracts from iVan-grown cultures, low levels of activity are observed towards Ver. As discussed above, IvaA plus IvaB is approximately 2 times more active towards Ver than towards iVan (Table 4), yet relative to oxygenase activity observed with iVan, ca. 10 times less activity was observed towards Ver with whole cells of iVan-grown cultures and ca. 2.5 times less activity towards Ver with cell extracts from iVan-grown cultures (Table 2 and Results). It may be that uptake of Ver is restricted in iVan-grown cells (see more below regarding IvaK and uptake of Ver), and the moderately higher activity levels towards Ver observed in cell extracts support this suggestion. However, one would still expect Ver to have induced higher activity levels than iVan in cell extracts. This question was not explored further.

Release of iVan and Van during growth on Ver.

Cultures of strain BR6020 growing on Van and iVan take up the substrates without release of aromatic compounds (see Results). In contrast, cultures growing on Ver transiently release Van and iVan into the culture medium and then take them up again once Ver is completely consumed (Fig. 2). The higher concentration of Van relative to iVan in the culture medium (Fig. 2) is likely because of higher activity towards Ver by IvaA plus IvaB relative to VanA plus IvaB (Table 4) which, in vivo, could result in more Van being produced relative to iVan. However, we are unsure why the O demethylation products of Ver (which are presumably formed in the cytoplasm) are released by cells in the first place. It may be that uptake of Ver from the extracellular environment is mediated by an antiporter-like system, which results in (or relies on) extrusion of Van and iVan from the cytoplasm.

ORFs associated with vanA and ivaAB.

Nine other ORFs physically linked to vanA and ivaAB were identified (Fig. 3A and Table 3). VanR is likely a transcriptional regulator of the van-iva genes on the basis of its similarity to VanR of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (25). Similarly, IvaR may be a (another) transcriptional regulator of the van-iva genes on the basis of its homology to MarR-like proteins, a group whose members respond to aromatic compounds and/or control expression of catabolic genes for various aromatic compounds (31). Our current hypothesis is that IvaR controls expression of genes induced by iVan, while VanR controls expression of genes induced by Van and Ver (discussed above). In our model, IvaR also responds to Van (and possibly Ver), which would explain why growth on Van also induces expression of the region from ivaK to ivaC. IvaK, which shows homology to VanK of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (17), may mediate uptake of iVan and possibly Van, but apparently not Ver. This is based on the observations that even though ivaK is expressed in Van-, Ver-, and iVan-grown cultures (Fig. 5B), activity towards Ver is extremely low in whole cells of iVan-grown cultures (discussed above). This suggests that Ver uptake is poor in iVan-grown cells and that some other transport system likely mediates Ver uptake in Van- and Ver-grown cultures. With respect to ctb1, ctb2, ctb3, ivaC, ctb4, and ctb5 (Table 4 and Fig. 3), their role (if any) in metabolism of iVan, Van, or Ver remains to be elucidated.

Comparison of van-iva locus to other vanAB-containing loci.

Functionally characterized VanAB-encoding loci have been described in five other bacteria (see introduction), and there are some interesting differences among these loci and the one reported here (graphically summarized in Fig. 3B). For example, the VanAB-encoding genes in strain BR6020 (vanA and ivaB) are not adjacent to each other as in the other four loci but are separated by three genes. Instead, ivaA is adjacent to ivaB. In addition, while a gene coding for an IvaK-like protein is in the locus from strain ADP1, and genes coding for VanR-like proteins are present in the loci from strains ADP1, HR199, and WCS358, their physical organization and direction of transcription relative to the respective VanA-encoding genes vary.

Concluding remarks.

In summary, this report describes the biochemistry and genetics of iVan, Van, and Ver metabolism in C. testosteroni strain BR6020. The compact manner in which the catabolic genes for these substrates are organized and the distinct way in which they are expressed suggest that the van-iva locus may have evolved for efficient metabolism of Ver rather than solely for metabolism of Van or iVan. Work with Nocardia spp. (15, 24) indicates that a pathway similar to the one described here may be present in this group of bacteria; not only do Nocardia spp. have oxygenase induction patterns towards Van, iVan, and Ver identical to those described here, but they also release Van and iVan into the growth medium when they are grown on Ver.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Tewes Tralau with RT-PCR work and Karin Denger, Jacques Niles, and William Willmore with HPLC analyses.

M.A.P. was the recipient of postdoctoral fellowships from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A.M.C. and NSERC to I.B.L.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of R. Campbell Wyndham (1951-2002).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, T., E. Masai, K. Miyauchi, Y. Katayama, and M. Fukuda. 2005. A tetrahydrofolate-dependent O-demethylase, LigM, is crucial for catabolism of vanillate and syringate in Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. J. Bacteriol. 187:2030-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Rodriguez, M. L., C. Belloch, M. Villa, F. Uruburu, G. Larriba, and J. J. R. Coque. 2003. Degradation of vanillic acid and production of guaiacol by microorganisms isolated from cork samples. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbe, V., D. Vallenet, N. Fonknechten, A. Kreimeyer, S. Oztas, L. Labarre, S. Cruveiller, C. Robert, S. Duprat, P. Wincker, L. N. Ornston, J. Weissenbach, P. Marliere, G. N. Cohen, and C. Medigue. 2004. Unique features revealed by the genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. ADP1, a versatile and naturally transformation competent bacterium. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:5766-5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman, A., L. Coin, R. Durbin, R. D. Finn, V. Hollich, S. Griffiths-Jones, A. Khanna, M. Marshall, S. Moxon, E. L. L. Sonnhammer, D. J. Studholme, C. Yeats, and S. R. Eddy. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D138-D141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batie, C. J., D. P. Ballou, and C. C. Correll. 1991. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases. Chem. Biochem. Flavoenzymes 3:543-556. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunel, F., and J. Davison. 1988. Cloning and sequencing of Pseudomonas genes encoding vanillate demethylase. J. Bacteriol. 170:4924-4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buswell, J. A., and D. W. Ribbons. 1988. Vanillate O-demethylase from Pseudomonas species. Methods Enzymol. 161:294-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartwright, N. J., and J. A. Buswell. 1967. The separation of vanillate O-demethylase from protocatechuate 3,4-oxygenase by ultracentrifugation. Biochem. J. 105:767-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cartwright, N. J., and A. R. W. Smith. 1967. Bacterial attack on phenolic ethers: an enzyme system demethylating vanillic acid. Biochem. J. 102:826-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow, K. T., M. K. Pope, and J. Davies. 1999. Characterization of a vanillic acid non-oxidative decarboxylation gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. D7. Microbiology 145:2393-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Civolani, C., P. Barghini, A. R. Roncetti, M. Ruzzi, and A. Schiesser. 2000. Bioconversion of ferulic acid into vanillic acid by means of a vanillate-negative mutant of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain BF13. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2311-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, S. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Skelton, S. Squares, R. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford, R. L. 1981. Lignin biodegradation and transformation. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 15.Crawford, R. L., E. McCoy, J. M. Harkin, T. K. Kirk, and J. R. Obst. 1973. Degradation of methoxylated benzoic acids by a Nocardia from a lignin-rich environment: significance to lignin degradation and effect of chloro substituents. Appl. Microbiol. 26:176-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford, R. L., and P. Perkins-Olson. 1978. Microbial catabolism of vanillate: decarboxylation to guaiacol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36:539-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, W. M. Coco, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J. Bacteriol. 181:3505-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Mansi, E. M. T., and S. C. K. Anderson. 2004. The hydroxylation of vanillate and its conversion to methoxyhydroquinone by a strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens devoid of demethylase and methylhydroxylase activities. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:827-832. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson, D. T., and R. E. Parales. 2000. Aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases in environmental biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junker, F., R. Kiewitz, and A. M. Cook. 1997. Characterization of the p-toluenesulfonate operon tsaMBCD and tsaR in Comamonas testosteroni T-2. J. Bacteriol. 179:919-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy, S. I. T., and C. A. Fewson. 1968. Enzymes of mandelate pathway in bacterium NCIB 8250. Biochem. J. 107:497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirk, T. K., and R. L. Farrell. 1987. Enzymatic “combustion”: the microbial degradation of lignin. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41:465-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locher, H. H., T. Leisinger, and A. M. Cook. 1991. 4-Sulphobenzoate 3,4-dioxygenase: purification and properties of a desulphonative two-component enzyme system from Comamonas testosteroni T-2. Biochem. J. 274:833-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malarczyk, E. 1984. Substrate-induction of veratric acid O-demethylase in Nocardia sp. Acta Biochim. Pol. 31:383-395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morawski, B., A. Segura, and L. N. Ornston. 2000. Repression of Acinetobacter vanillate demethylase synthesis by VanR, a member of the GntR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parke, D. 1992. Application of p-toluidine in chromogenic detection of catechol and protocatechuate, diphenolic intermediates in catabolism of aromatic compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2694-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pometto, A. L., III, J. B. Sutherland, and D. L. Crawford. 1981. Streptomyces setonii: catabolism of vanillic acid via guaiacol and catechol. Can. J. Microbiol. 27:636-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priefert, H., J. Overhage, and A. Steinbuchel. 1999. Identification and molecular characterization of the eugenol hydroxylase genes (ehyA/ehyB) of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. Arch. Microbiol. 172:354-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Priefert, H., J. Rabenhorst, and A. Steinbüchel. 1997. Molecular characterization of genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 involved in bioconversion of vanillin to protocatechuate. J. Bacteriol. 179:2595-2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Providenti, M. A., J. Mampel, S. MacSween, A. M. Cook, and R. C. Wyndham. 2001. Comamonas testosteroni BR6020 possesses a single genetic locus for extradiol cleavage of protocatechuate. Microbiology 147:2157-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Providenti, M. A., and R. C. Wyndham. 2001. Identification and functional characterization of CbaR, a MarR-like modulator of the cbaABC-encoded chlorobenzoate catabolism pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3530-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribbons, D. W. 1971. Requirement of two protein fractions for O-demethylase activity in Pseudomonas testosteroni. FEBS Lett. 12:161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribbons, D. W. 1970. Stoichiometry of O-demethylase activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEBS Lett. 8:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schläfli Oppenberg, H. R., G. Chen, T. Leisinger, and A. M. Cook. 1995. Regulation of the degradative pathways from 4-toluenesulphonate and 4-toluenecarboxylate to protocatechuate in Comamonas testosteroni T-2. Microbiology 141:1891-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segura, A., P. V. Buenz, D. A. D'Argenio, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. Genetic analysis of a chromosomal region containing vanA and vanB, genes required for conversion of either ferulate or vanillate to protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. J. Bacteriol. 181:3494-3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sze, I. S., and S. Dagley. 1987. Degradation of substituted mandelic acids by meta fission reactions. J. Bacteriol. 169:3833-3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatusov, R. L., D. A. Natale, I. V. Garkavtsev, T. A. Tatusova, U. T. Shankavaram, B. S. Rao, B. Kiryutin, M. Y. Galperin, N. D. Fedorova, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tralau, T., A. M. Cook, and J. Ruff. 2003. An additional regulator, TsaQ, is involved with TsaR in regulation of transport during the degradation of p-toluenesulfonate in Comamonas testosteroni T-2. Arch. Microbiol. 180:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venturi, V., F. Zennaro, G. Degrassi, B. C. Okeke, and C. V. Bruschi. 1998. Genetics of ferulic acid bioconversion to protocatechuic acid in plant-growth-promoting Pseudomonas putida WCS358. Microbiology 144:965-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyndham, R. C. 1986. Evolved aniline catabolism in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus during continuous culture of river water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:781-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyndham, R. C., R. K. Singh, and N. A. Straus. 1988. Catabolic instability, plasmid gene deletion and recombination in Alcaligenes sp. BR60. Arch. Microbiol. 150:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]