Abstract

Researchers have worked to delineate the manner in which urban environments reflect broader social processes, such as those creating racially, ethnically and economically segregated communities with vast differences in aspects of the built environment, opportunity structures, social environments, and environmental exposures. Interdisciplinary research is essential to gain an enhanced understanding of the complex relationships between these stressors and protective factors in urban environments and health. The purpose of this study was to examine the ways that multiple factors may intersect to influence the social and physical context and health within three areas of Detroit, Michigan. We describe the study design and results from seven focus groups conducted by the Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP) and how the results informed the development of a survey questionnaire and environmental audit tool. The findings from the stress process exercise used in the focus groups described here validated the relevance of a number of existing concepts and measures, suggested modifications of others, and evoked several new concepts and measures that may not have been captured without this process, all of which were subsequently included in the survey and environmental audit conducted by HEP. Including both qualitative and quantitative methods can enrich research and maximize the extent to which research questions being asked and hypotheses being tested are driven by the experiences of residents themselves, which can enhance our efforts to identify strategies to improve the physical and social environments of urban areas and, in so doing, reduce inequities in health.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, Neighborhood assessment, Qualitative and quantitative methods, Stress process model

Introduction

Understanding relationships between urban environments and the health of their residents is increasingly central to public health as the proportion of the world’s population living in urban centers expands.1,2 From early epidemiological efforts to identify the location of contaminated wells3 to more recent efforts to uncover the implications of the location of grocery stores for dietary intakes,4 researchers have understood the important role played by urban environments in shaping the public's health.1 In recent years, researchers have worked to delineate the manner in which local environments reflect broader social processes.1–5 For example, physical and social aspects of the places in which we reside influence exposures to potentially deleterious factors such as, air pollution, deteriorated built environments, discrimination, and poverty.6,7 Aspects of urban places also affect the resources available to protect or promote health, for example, the availability and quality of health services,7–9 behaviors, such as the extent to which we walk or drive in cars to destinations, the types of foods available to eat, and the types of social relationships we are able to establish. Each of these factors, which are shaped by more fundamental ethnic, racial and socioeconomic inequalities, may be experienced differently by individuals of differing genders, ages, and economic resources and contribute to ethnic, racial and socioeconomic inequities in health.9,10

These inequities in health are seen in rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the largest contributor to all-cause mortality in the United States: CVD accounts for one-third of the excess mortality experienced by African Americans as compared to whites.11 Over the past 30 years both racial and socioeconomic disparities in CVD risk have increased.12,13 Although disparities have been well established between African Americans and whites, patterns of CVD risk and mortality among Mexican Americans are less conclusive.14–19 Understanding the dynamic processes through which fundamental, intermediate and proximate factors 9—also referred to as stressors and conditioning or protective factors—in urban environments7,20 are associated with and influence inequities in CVD is critical for public health professionals, particularly in communities which disproportionately experience CVD.

Multidisciplinary, theoretically informed research is essential to gain an enhanced understanding of the complex relationships between stressors and protective factors in urban environments and health.1 Research that draws upon both qualitative and quantitative methods can enrich the research through a process of identifying, theorizing and testing relationships between individuals and the contexts in which they reside and maximize the extent to which research questions being asked and hypotheses being tested are driven by the lived experiences of the residents themselves.1,21–23

In this article, we describe the study design and results from seven focus groups conducted by the Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP), a community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership in Detroit, Michigan. We describe the process we used to elicit the perspectives and experiences of white, African American and Latino women and men from eastside, northwest and southwest neighborhoods in Detroit to understand how both social circumstances and neighborhood environments might influence their health. We present results from these focus groups, describe how the findings informed the development of a survey questionnaire and an environmental audit tool, and discuss the limitations and implications for future research and interventions.

Background

The Detroit Healthy Environments Partnership

HEP was initiated in October 2000 and is affiliated with the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center (URC).24 The overall aims of HEP are to investigate the prevalence of biological indicators of CVD risk and the role of social and physical environmental exposures to those risk factors, with implications for proximate factors such as health-related behaviors, psychosocial stressors and responses, and social integration and to disseminate and translate findings to inform new and established intervention and policy efforts.9

As a CBPR project,25–27 HEP engages partners based in academic institutions, health practice organizations and community-based organizations in a collaborative effort to address these aims (see Acknowledgements for list of partners). The CBPR principles that guide HEP's work emphasize involving all partners in all major phases of the research process, conducting research that is beneficial to the communities involved, and disseminating findings to community members in ways that are understandable and useful (see Israel et al.25 for a more complete description of these principles). In keeping with these principles, representatives of the partner organizations comprise the HEP Steering Committee (SC), which meets monthly and was actively involved in the development, implementation, interpretation and application of results of the focus groups described below.

Why Detroit?

A thriving and prosperous community with a strong blue collar middle class for much of the twentieth century, like many similar urban areas, Detroit experienced population out-migration and economic disinvestment beginning in the 1950s, escalating in the 1970s and 1980s.28 These economic and population shifts were fueled by white fears of racial integration and the departure of the majority of the city's white residents to suburban neighborhoods as African American residents moved into previously all-white Detroit neighborhoods.29 The racial composition of Detroit shifted from 16% African American in 1950 to 82% African American in 2000.30 For the two decades preceding this study, Detroit was among the most racially segregated large urban areas in the United States.28,29,31 The total Latino population in Detroit increased steadily between 1970 and 2000, with the largest increase occurring between 1990 and 2000, when the Latino population almost doubled, growing from 2.8 to 5% of Detroit's total population.32

These trends have played out differently in different areas of the city. For example, Detroit's eastside (97% African American in both 1990 and 2000) is one of the oldest areas of the city, reflected in the age of the housing stock. In part as a result of federal housing policies and programs in the 1960s and 1970s, this area lost 46% of its population between 1950 and 1980, and by the 1970s nearly 30% of the lots in this area of the city were vacant or unattended.33 Southwest Detroit is home to the majority of the city's Mexican American and other Latino residents, with approximately 50% Latino, 35% African American and 15% white residents.34 This part of the city experiences a substantial daily volume of truck traffic and industrial sites, including railway shipping and docking facilities, metals factories, and an automobile distribution center,35,36 with residents exposed to a variety of environmental hazards.37 Northwest Detroit was long the area of the city in which the majority of the city's police and fire fighters lived. Residency requirements were removed in 1999, and between 1990 and 2000, the population of Detroit's northwest area declined by 27%. It remains, however, one of the areas of the city with the lowest rates of poverty.32

Neighborhoods and Health

The extent to which neighborhood conditions contribute to health disparities above and beyond the effects of individual or household social status is a matter of considerable interest. Several studies have linked residence in areas of economic divestment and race-based segregation to poorer health outcomes.38,39 Research to date has established that characteristics of neighborhoods assessed using census and administrative data are linked to a variety of social and health outcomes, including all cause mortality,40,41 cardiovascular disease,37,42 and access to grocery stores.4,43 Current research focuses on establishing more clearly the pathways through which neighborhood environments are linked to health outcomes through, for example, assessing observed characteristics of neighborhood environments44,45 and how those characteristics are experienced by residents, the meanings that they hold, and physiological and behavioral responses to those environments.

Stress Process Models

Extensive research has examined the relationships between stressors and health outcomes, much of it focused on individual stressors aggregated to the population level. These population-based results provide important evidence that there are multiple factors and pathways through which stress is associated with health.7,46–49 The HEP project has used a stress process framework to examine relationships among social processes, social context, stress, and health outcomes.

This model of stress and health was developed initially by researchers at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research50–52 and later adapted by other researchers at the University of Michigan.7,20,53,54 Stress is seen as a complex and dynamic process in which social and physical environmental conditions conducive to stress or stressors (e.g., major life events, daily hassles, chronic strains, ambient exposures), perceived stress (e.g., stressors perceived as bothersome or result in a physiological adaptational response), short term responses (e.g., elevated blood pressure, tenseness), and conditioning variables or protective factors (e.g., social support, personal control, physical activity) all affect each other and long term health outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular disease, anxiety disorders).7,55,56

Purpose of Focus Groups

As delineated in the stress process model, residents' experience of their neighborhoods involves subjective responses to conditions in their physical and social environments. The use of qualitative methods, in particular focus group interviews, is a viable approach for gaining a more in-depth understanding of such subjective responses57,58 and for informing more quantitative assessments of the relationships between these complex conditions and responses.21 The intent of these focus groups was to understand the particular range and types of stressful life conditions that participants experienced as aspects of their neighborhood and social environments and the ways in which they responded to those environments. The results from the focus groups were also intended to inform items on a structured closed-ended survey questionnaire and the environmental audit tool, the Neighborhood Observational Checklist or NOC, that were to be administered over the following 2 years.6,23 In addition, because HEP is a CBPR effort intended to examine and inform community residents and others about the relationships between the urban environment and health, the focus groups were an opportunity to begin to engage community residents in discussions of these connections.

The Stress Process Exercise

The focus group interview protocol we used was adapted from a “stress process exercise” initially developed by Israel and Schurman and their colleagues20 for use in an industrial, organizational context. The exercise offers a means to initiate discussion about relationships between the social environment and health by asking a series of five questions, each of which relates to a portion of the stress process model. This exercise and series of questions was originally used in group situations where the questions were initially answered individually, then shared and discussed with one other person, and finally shared in a large group discussion (see Israel et al.20 and Schulz et al.59 for more details). This process was altered to use the series of questions in a more traditional focus group interview format.57

This exercise serves several functions: (1) it allows individuals and groups to identify common stressors in their social and physical environments, responses to those stressors, and to discuss their implications for health and well being; (2) it provides an opportunity to broaden definitions of health and well being beyond the individual and beyond health behaviors and health services and to understand health as produced within a social context; (3) it provides opportunities to discuss individuals' experiences of stressful life conditions, social relationships and health and to validate those experiences through bringing in a well-established literature; (4) it informs the development of more widespread assessments of stress and health through, for example, survey methodology;20,59 and (5) it offers opportunities for individuals and groups to discuss the potential to intervene in the processes that link social inequalities, stressors and health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Eight focus groups were convened with residents of the three areas of the city involved with the HEP project. (One focus group, conducted on Detroit's east side with African-American men, included only two participants. Given this small size, the results of this focus group are excluded here.) We wanted to ensure representation of participants from the diverse ethnic groups in the three areas of the city and to engage adults over the age of 25 years, consistent with the study aims. The HEP community partners were instrumental in recruiting participants and organizing these groups. Their recruitment strategies included identifying and inviting participants from their social networks, distributing fliers to staff and participants at their community-based organizations, and posting fliers at other locations throughout the community. The interviews were conducted at sites within the involved communities (e.g., churches, community-based organizations). Recognizing that people may experience the stress process differently based on neighborhood, race/ethnicity, and gender, and that individuals may be more comfortable sharing information and ideas with persons similar to themselves, we organized the focus groups by these factors. There were three focus groups in northwest Detroit: one each with white women (n = 10), white men (n = 8), and African American women (n = 11). Four focus groups were conducted in southwest Detroit, one each with English language dominant (n = 7) and Spanish language dominant Latinas (n = 8) and also English language dominant (n = 4) and Spanish language dominant Latinos (n = 9). These focus groups were supplemented by a previous study, which had gathered extensive material regarding the stress process model experienced by African American women on Detroit's eastside.60–62 Given the existence of this data, we did not consider it necessary to conduct another focus group with African-American women on Detroit's east side. The majority (49%) of participants were between the ages of 36 and 55; 17.5% were between 18 and 35, and 28% were over age 55 (age data was not available for the remaining participants, 5.2%). While we did not assess the socioeconomic status of the participants, the median household income in 2000 was $20,811 in eastside Detroit, $24,956 in southwest, and $33,628 in northwest.32

Facilitation

Each focus group was facilitated by a team that included a facilitator responsible for asking the questions and guiding the discussion a recorder responsible for monitoring the tape recorder and taking field notes of the discussion and a note taker who recorded all responses on newsprint on the wall. A fourth individual was responsible for ensuring that all participants completed informed consent statements and demographic information and ensuring commitment to confidentiality forms, refreshments, child care, and payment of participants following the focus group (each participant received $25). To the extent possible, members of the facilitation team for the focus group were matched with participants on race and ethnicity, gender and language (Spanish or English). While no one individual attended all focus groups, consistency was assured across the groups through the systematic training of facilitators and notetakers and the use of a standardize interview protocol and notetaking procedures. The length of the focus group interviews was time limited to 1 1/2 h and each group lasted approximately that time period.

As focus group participants arrived, team members welcomed them and distributed and explained the forms that they needed to sign. At the beginning of each session, facilitators thanked participants for coming, summarized the purpose of the study, gave an overview of the purpose of the focus group to help guide the discussion, and introduced ground rules to help guide the discussion (e.g., only one person speaks at a time, agree to disagree, there are no right or wrong answers).

Given that the original version of the stress process exercise had been conducted with English speaking white and African American participants, questions were raised in the research team regarding the extent to which the concept of “stress” would be meaningful and appropriate for participants in the Latino focus groups. We decided to begin all focus groups with the following question “We are trying to understand the challenges and major changes that people experience in their lives, in their families, and in their communities that require making adjustment. Some people describe these changes or challenges as creating “stress” (estres) for them. Is this the word that you use? Or are there other words that you would use that mean “stress” to you, or that people use to say that they are feeling stressed?”

Following discussion of the first item, the facilitator asked a series of three questions sequentially: 1) What are the things that create stress for you or for other women/men living in your neighborhood (i.e., Eastside, Southwest, or Northwest Detroit)? You may want to think about your own experiences or the experiences of your neighbors or friends as you think about this question; 2) How do you, or other women/men in your community, feel when those things happen?; and 3) How do you, or other women/men in your community, respond when those things happen, or when you feel that way? The note taker recorded responses on three adjacent newsprint sheets, using the left-hand sheet to record stressors, the middle sheet to record feelings, and the right-hand sheet to record responses. In each case, the facilitator encouraged all focus group participants to share their experiences, using follow-up probes to obtain clarification and more in-depth explanation, as needed. The facilitator summarized the answers that had been shared and asked the fourth question: “When these things go on day after day, day in and day out, week after week, month after month, how does that affect you? Other women/men in your community?” The note taker recorded responses on a fourth sheet of newsprint, with the facilitator encouraging additional responses.

Finally the facilitator stated: “We have talked about a lot of experiences that people may have that can contribute to these feelings of stress, tension, worry and the ways that they affect us, our friends, family and neighbors. How come not everyone is experiencing all of these negative effects? What are the things that keep it from being so bad?” Responses to this question were recorded on a fifth sheet of newsprint. The facilitator ended the session by thanking participants for their involvement, summarizing the value of their contributions and how the information would be used, informing them that they would receive a summary of the themes and a booklet about resources available to address some of the stressors identified.

Data Analysis

Analysis of the themes from the focus group proceeded in two stages. We conducted a “summary analysis” process using a team approach involving the note takers, facilitators and recorders to generate an initial rapid analysis of key themes and issues raised in the focus groups.63 The note taker was responsible for typing up notes written on the newsprint. For each group, facilitators and recorders completed a form that included a summary of responses for each question and a description of their impressions of the focus group discussion, including any information that might be important in the interpretation of the findings (e.g., disruptions). A summary analysis meeting was held with the facilitation team and additional members of the research team to share and discuss the key themes identified on the summary forms and typed notes and similarities and differences across groups. A typed report of the results of these summary analysis meetings was shared with the SC. In the second stage of the data analysis, tapes from each focus group were transcribed and themes were generated within and across focus groups by a member of the research team, using a process of focused coding and constant comparison.55,64 The team member responsible for this process systematically compared the themes from the focus groups with those listed on the newsprint sheets to ensure comprehensive coverage of themes, and these themes were reviewed with the principal investigator of the project. The results of this more systematic analysis provided a more detailed listing of the themes and issues raised in the focus group interviews.

Results

Results from the first question asked and analyzed across the focus groups suggested that the word “stress” was appropriate for use across racial, ethnic, gender and language groups. While focus group participants used a wide range of other terms interchangeably with the word “stress,” including for example, burned out, overwhelmed, fatigued, worried, anxious, angry/aggravated and, among the Spanish speaking groups, nervios, preocupada, and estresada, results from this process suggest that the term “stress” resonated with and was meaningful to participants across groups.

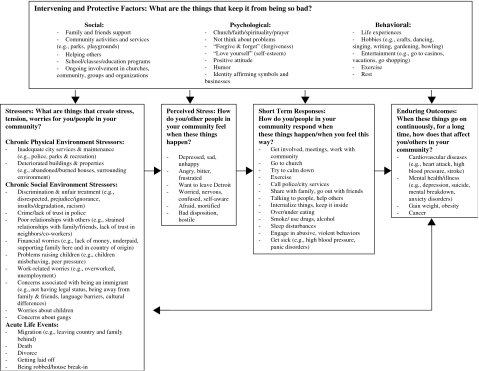

A summary of the key findings of the focus groups is provided in Fig. 1, organized according to the stress model. Several themes occurred across many or most of the focus groups. For example, stressors associated with inadequate city services and maintenance, concerns about crime, lack of trust in police, financial worries, problems with deteriorated buildings, worries about children, and experiences of discrimination, were named by participants in all or most of the focus groups (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the stress process identified through focus groups with Detroit residents.

Some themes arose only in one or two groups. For example, the lack of retail stores in the community was mentioned only in focus groups conducted in the city's northwest side, while concerns associated with undocumented status and language barriers were mentioned only in the Latino/a groups.

In response to the question regarding how people feel when these stressors happen to them, the key themes identified include: depressed/sad/unhappy, angry/bitter/frustrated, want to leave Detroit, worried/nervous, afraid, and hostile (see Fig. 1). In turn, respondents identified a number of responses or actions they take when they feel this way, including: get involved in the community, go to church, exercise, call police/city services, over/under eating, smoke/use drugs/alcohol, sleep disturbances (see Fig. 1). Participants also identified a number of enduring outcomes that occur when this stress process continues for a long time, including cardiovascular diseases (e.g., heart attack, stroke), mental health/illness (e.g., depression, mental breakdown), and cancer (see Fig. 1).

Results from analysis of the focus group question regarding “things that make it not so bad” reflect a wide range of intervening or protective factors (see Fig. 1). These include, but were not limited to, social factors, such as support from family and friends, community activities and services, ongoing involvement in churches, and community-based organizations; psychological factors, such as faith/spirituality/prayer, coping responses (e.g., not think about problems), positive attitude, identity affirming symbols and businesses; and behavioral factors, such as hobbies (e.g., gardening), entertainment (e.g., shopping), and exercise.

Application of Results

As depicted in Table 1, the results from the focus groups were used by the research team and SC to guide the development of the survey instrument and the NOC used subsequently in the study to assess similarities and differences across groups and areas of the city in a more systematic manner.6,23 The focus group themes informed the inclusion of certain measures in the questionnaire and NOC in the following ways (see Table 1 and examples provided below): (1) the theme identified validated that it was appropriate to use an existing measure as is, hence the “same item” was used in the questionnaire or NOC; (2) an existing measure was “modified” to more accurately reflect the theme identified through the focus groups; and (3) a theme was identified for which no existing measure was found and hence a new measure was “created” for the survey or NOC.

Table 1.

Examples of selected measures informed by focus group themes included in the HEP survey and Neighborhood Observational Checklist (NOC)

| Focus group theme | Original existing item and source | Survey/NOC measures used |

|---|---|---|

| Stressors/Perceived stress | ||

| Chronic physical environment: inadequate city services and maintenance | Landfill or city garbage dump: Would you say these are present, or not present?68 | Modified NOC Item: Are there any piles of garbage or dumped materials on the block face? |

| Chronic physical environment: deteriorated buildings and properties | HEP created | Created Survey Item: Houses in my neighborhood are generally well maintained. |

| Chronic physical environment: tractor trailer/truck traffic | Volume of traffic (Check one), 1) No traffic, 2) Light (occasional cars), 3) Moderate, 4) Heavy (steady stream of cars)69 | Modified NOC Item: Volume of traffic (Mark one), 1) Heavy (steady stream of cars, trucks, or motorcycles), 2) Moderate, 3) Light (occasional cars, trucks, or motorcycles), 4) No traffic |

| Chronic social environment: worries about children | HEP created | Created Survey Item: How often did you wonder whether your child(ren) was/were getting the education they need to prepare for the life ahead of them? |

| Chronic social environment: discrimination and unfair treatment | In your day-to-day life, how often do any of the following things happen to you? (e.g., treated with less courtesy and respect than others...)56 | Modified Survey Item |

| Added reasons | ||

| because I live in Detroit | ||

| because I do not speak English | ||

| Chronic social environment: factors associated with being an immigrant | HEP created | Created Survey Item: It is a problem for me when service providers (such as health care providers) don't speak Spanish |

| Intervening and protective factors | ||

| Social: friends and family support | If you needed help around the house, for example with cleaning or making small repairs, how often could you get somebody to help without paying them?70 | Same Survey Item |

| Social: neighborhood and/or community meetings, events, gatherings, community-based organizations, church | In the past 12 months, have you served on a committee, helped organize meetings, or served in a position of leadership in the church or other place of worship?59 | Modified Survey Item: Have you served on a committee, helped organize meetings, or served in a position of leadership for any local organization, such as a block club, church, parent–teacher, or other school organization, or any other organization? |

| Psychological: church, faith, spirituality | Thought about spiritual matters to stop thinking about my problems.71 | Modified Survey Item: My spiritual beliefs help me to get through hard times. Would you say... completely true, somewhat true, somewhat false, or completely false |

| Psychological: identity affirming symbols and businesses | HEP created | Created NOC Item: Does any business or institution have a sign or advertisement in Spanish (e.g., a “Se Habla Español” sign) on the building or property? |

| Short term responses | ||

| Get involved, meetings, work with community | Participated in a neighborhood clean up or beautification project, crime watch or other neighborhood activity.72 | Modified Survey Item: Have you participated in a neighborhood clean up or beautification project, crime watch, Angel's Night, or other neighborhood activity? |

| Smoke/Use drugs or alcohol | Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?73 | Modified Survey Item: Have you ever smoked cigarettes regularly? |

| Get sick (e.g., high blood pressure, panic disorders) | Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure?74 | Modified Survey Item: Has a doctor or other health care professional ever told you that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure? |

| Enduring outcomes | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had congestive heart failure?74 | Same Survey Item |

| Cancer | Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?74 | Modified Survey Item |

| Mental health: depression | During the past 12 months, was there ever a time when you felt sad, blue, or depressed for two weeks or more in a row?75,76 | Same Survey Item |

| Mental health: depression | HEP created | Created Survey Item: Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with depression? |

Discrimination or the experience of being treated unfairly was articulated as a stressful experience shared across the focus groups conducted by HEP. A measure of discrimination developed and validated by Williams and colleagues56 was used on the HEP questionnaire to assess these stressors more systematically. However, two attributions which emerged from the focus groups as the “cause” of being treated poorly—living in Detroit and not speaking English—were added as response categories to the Williams' scale (see Table 1).

The importance of measuring deteriorated buildings and properties was confirmed as relevant to the HEP questionnaire as things that created stress for community residents. We modified one item on the questionnaire, initially framed as a stressor (e.g., “My neighborhood has a lot of vacant lots or vacant homes”), so that respondents could also identify positive aspects of their neighborhoods (i.e., “Houses in my neighborhood are generally well-maintained”—see Table 1). This decision was made in consultation with Detroit partners who were concerned that consistent negative framings of Detroit environments contributed to stigmatization of the city and its neighborhoods. Measures of the presence of vacant lots and condition of residential and non-residential buildings and grounds were included on the NOC.

Focus group findings from the “things that make it not so bad” question were also used (see Table 1) to confirm existing measures of, for example, friends and family support to modify existing measures related to spirituality and to create new measures for the NOC to assess identity affirming symbols and businesses. In this latter instance, we used these themes to develop items used in the survey as well as the NOC to identify community resources such as the presence of local businesses that cater to the Latino/a community and ethnic festivals that may preserve a positive sense of connection to an ethnic community. Such identity preserving symbols may buffer the negative effects of unfair treatment or discrimination.65,66

As shown in Table 1, the focus group themes informed a number of existing, modified and newly created items that were used in the survey questionnaire to assess short term responses (e.g., smoke/use drugs) and enduring outcomes (e.g., depression) in the stress process. (For additional detail on the HEP survey and NOC, see Schulz et al.6 and Zenk et al.23, respectively.)

Discussion

Limitations

The results presented here are from a limited number of focus groups conducted across three racial and ethnic groups in three areas of Detroit, and due to the small size of the African-American male focus group on the eastside, we were not able to include that data. Thus, these focus groups do not meet established requirements of saturation in the qualitative literature for drawing conclusions or for building theory.55 Neither are they appropriate for disentangling stressors experienced by neighborhood area from racial or ethnic group or gender status, given the non-random and non-representative nature of the sample. Results reported here are appropriately interpreted as indicative of a range of experiences described by residents across racial/ethnic groups, across areas of the city and across genders. To test the extent to which different aspects of the stress process model vary across these factors, data collected and analyzed systematically using comprehensive sampling strategies and quantifiable means such as a random sample survey and observational checklist are needed. In addition, the use of focus groups must always be examined critically for sources of bias. Stressors or responses to stress that may be considered less acceptable (for example, use of substances as a response to stress) may be less likely to be elicited in some focus groups, and these pressures may be exacerbated if participants know each other or are aware that they live in the same neighborhood. Community residents may hesitate to discuss some stressors within their communities with outsiders, aware of the contribution that those stressors may make to stigmatizing the neighborhoods themselves or the racial or ethnic groups that reside in those communities.9,67

Despite these limitations, the focus groups were an effective mechanism for engaging community residents in a conversation about aspects of their communities—both physical and social—that may promote health and those that may threaten health. We found that the language of “stress” was meaningful across groups and also that participants used a wide range of language to describe this phenomenon. Qualitative methods of data collection such as the focus groups described here can contribute to a better understanding of residents' experiences, perceptions, and responses to environmental conditions and the complexity of urban environments, the ways that individuals experience and interact with those environments, and implications for health.

The stress process exercise described here validated the relevance of a number of existing concepts and measures for use in collection of quantitative self-report and observational data.6 It also suggested specific modifications of several of these existing concepts and measures to enhance their applicability and usefulness in assessing relationships between social and physical environmental conditions and health among Detroit residents. Finally, results from these focus groups suggested several new concepts and measures for inclusion in the subsequent survey and environmental audit tool that allowed the study to capture dimensions of stressful life conditions and potential modifying factors that otherwise may not have been included. The use of a focus group exercise such as the one described here offers opportunities to identify a broad range of potential stressors and protective factors across race or ethnicity, citizenship, gender or many other characteristics that may influence the health of urban residents. It can help researchers assure that they are asking about the universe of factors that may be experienced by residents of particular urban communities and limit the risk that we underestimate life experiences due to a failure to ask the appropriate questions, or to ask the questions appropriately.

Finally, within the context of a CBPR effort, the use of a focus group approach to generate a stress process model provided an early opportunity for partners to hear directly from community members and gain an in-depth understanding of local contexts and experiences. Engaging academic, community and health practice partners in this process allowed us to build shared understandings of the potential implications of urban neighborhood environments for health and well being of their residents. Findings from this stress process exercise informed the development of the survey questionnaire and the Neighborhood Observational Checklist designed to assess perceived and observed characteristics of these urban communities more systematically and to test their relationships to health. The use of such an approach to learn from and to incorporate the perspectives and experiences of residents of urban communities can enhance our efforts to improve the physical and social environments of urban areas and, in so doing, reduce inequities in health.

Acknowledgements

The Healthy Environments Partnership () is a project of the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center (). We thank the members of the HEP Steering Committee for their contributions to the work presented here, including representatives from Boulevard Harambee, Brightmoor Community Center, Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, Southwest Detroit Environmental Vision, Southwest Solutions, University of Detroit Mercy, and the University of Michigan Schools of Public Health, Nursing and Social Work and Survey Research Center. HEP is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), #R01 ES10936. The results presented here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIEHS. Finally, we thank Sue Andersen for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Israel, Schulz, and Estrada-Martinez are with the University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1420 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029, USA; Zenk is with the University of Illinois, Chicago, IL, USA; Viruell-Fuentes is with the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Villarruel is with the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Stokes is with the University of Detroit-Mercy, Detroit, MI, USA.

References

- 1.Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:341–365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Galea S, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Cities and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1017–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Stanwell Smith R. The making of an epidemiologist: John Snow before the episode of the Broad Street pump. Commun Dis Public Health. 2002;5(4):269–270. [PubMed]

- 4.Zenk S, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and supermarket accessibility in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Schulz AJ, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health and environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4):455–471. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Schulz AJ, Zenk S, Kannan S, Israel BA, Koch MA, Stokes C. Community-based participatory approach to survey design and implementation: the Healthy Environments Partnership Survey. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, eds. Methods for Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2005:107–127.

- 7.Israel BA, Schurman SJ. Social support, control and the stress process. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 1990:187–215.

- 8.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Dvonch JT, et al. Social and physical environments and disparities in risk for cardiovascular disease: the Healthy Environments Partnership conceptual model. Environ Health Perspec. 2005;113:1817–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. New Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:173–188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cooper R, Cutler JA, Desvigne-Nickens P, et al. Trends and disparities in coronary heart disease, stroke and other cardiovascular diseases in the United States: findings of the national conference on cardiovascular disease prevention. Circulation. 2000;102(25):3137–3147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hunt KJ, Resendez RG, Williams K, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality among Mexican American and non-Hispanic white older participants in the San Antonio heart study—evidence against the “Hispanic paradox.” Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(11):1048–1057. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Luepker RV. Cardiovascular disease among Mexican Americans [editorial]. Am J Med. 2001;110(2):147–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Pandey DK, Labarthe DR, Goff Jr. DC, Chan W, Nichaman MZ. Community-wide coronary heart disease mortality in Mexican Americans equals or exceeds that in non-Hispanic whites: the Corpus Christi Heart Project. Am J Med. 2001;110:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(20):2464–2468. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Country of birth, acculturation status and abdominal obesity in a national sample of Mexican American women and men. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):470–477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Winkleby MA, Robinson TN, Sundquist J, Kraemer HC. Ethnic variation in cardiovascular disease risk factors among children and young adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 1999;281(11):1006–1113. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Israel BA, Schurman SJ, House JS. Action research on occupational stress: involving workers as researchers. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(1):135–155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hugentobler MK, Israel BA, Schurman SJ. An action research approach to workplace health: integrating methods. Health Educ Q. 1992;19(1):55–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Galea S, Schulz AJ. Methodologies for the study of urban health: how do we best assess how cities affect health? In Freudenberg N, Vlahov D, Galea S, eds. Cities and the Health of the Public. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2006; (in press).

- 23.Zenk S, Schulz AJ, House JS, Benjamin A, Kannan S. Application of community-based participatory research in the design of an observational tool: the neighborhood observational checklist. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, eds. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2005:167–187.

- 24.Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, et al. The Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center: development, implementation and evaluation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001;7(5):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health. 2001;14(2):182–197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(2):155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Farley R, Danziger S, Holzer HJ. Detroit Divided. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2000.

- 29.Sugrue TJ. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1996.

- 30.Schulz AJ, Williams DR, Israel BA, Lempert LB. Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milbank Q. 2002;80(4):677–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Glaeser EL, Vigdor JL. Racial Segregation in the 2000 Census: Promising News. Washington, District of Columbia: The Brookings Institution; 2001.

- 32.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census 2000. 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. Accessed June 2000.

- 33.City of Detroit. Planning Report: The East Sector. Preliminary Draft 1984. Detroit: Planning Department; 1984.

- 34.City of Detroit. Cluster 5 Demographic Profile Based on 2000 Census. Detroit: Planning and Development Department; 2000.

- 35.Gerald R Ford School of Public Policy. Regional Solutions to Urban Revitalization: A Policy Forum on Alternative Locations for a Detroit Metro Park. 2004. Available at: http://www.fordschool.umich.edu/academics/IPE2004/riverfront.htm. Accessed October 7, 2005.

- 36.Detroit News. Ambassador Bridge to Widen, Toll Roads. June 4, 2004. Available at: http://www.tollroadsnews.com/cgi-bin/a.cgi/k6zVkuf0EdiRW6r2jfFwDw. Accessed October 7, 2005.

- 37.LeClere FB, Rogers RG, Peters K. Neighborhood social context and racial differences in women's disease mortality. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(2):91–107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ellen IG, Mijanovich T, Dillman K-N. Neighborhood effects on health: exploring the links and assessing the evidence. J Urban Aff. 2001;23(3–4):391–408. [DOI]

- 39.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighborhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Waitzman NJ, Smith KR. Separate but lethal: the effects of economic segregation on mortality in metropolitan America. Milbank Q. 1998;76(3):341–373, 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Anderson RT, Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Kaplan GA. Mortality effects of community socioeconomic status. Epidemiology. 1997;8(1):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology, clinical science and beyond. Epidemiology. 1997;8(4):459–461. [PubMed]

- 43.Morland K, Wing S, Diez-Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Raudenbush SW. The quantitative assessment of neighborhood social environments. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, eds. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford University Press; 2003:112–131.

- 45.Caughy MO, O'Campo PJ, Patterson J. A brief observational measure for urban neighborhoods. Health and Place. 2001;7(3):225–236. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.McEwen BS. The End of Stress as We Know It. Washington, District of Columbia: Joseph Henry; 2002.

- 47.Karasek RT, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(7):694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of adaptation-allostatic load and its health consequences: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(19):2259–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Selye H. The Stress of Life. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1956.

- 50.French JRP, Kahn R. A programmatic approach to studying the industrial environment and mental health. J Soc Issues. 1962;18:1–48.

- 51.House JS. Work Stress and Social Support. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley; 1981.

- 52.Katz D, Kahn R. The Social Psychology of Organizations. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1978.

- 53.Baker EA, Israel BA, Schurman SJ. The integrated model: implications for worksite health promotion and occupational health and safety practice. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(2):175–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Israel BA, Checkoway BN, Schulz AJ, Zimmerman MA. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):149–170. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 1998.

- 56.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The Focus Group Kit. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 1997.

- 58.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, (eds.). Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2000.

- 59.Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Israel BA, Becker AB, Maciak BJ, Hollis R. Conducting a participatory community-based survey: collecting and interpreting data for a community health intervention on Detroit's east side. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1998;4(2):10–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Israel BA, Farquhar SA, Schulz AJ, James SA, Parker EA. The relationship between social support, stress and health among women on Detroit's east side. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):342–360. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Israel BA, DeCarlo M, Lockett M. Addressing social determinants of health through community-based participatory research: the East Side Village Health Worker Partnership. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(3):326–341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Parker EA, Lockett M, Hill Y, Wills R. The East Side Village Health Worker Partnership: integrating research with action to reduce health disparities. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(6):548–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kieffer EC, Salabarría-Peña Y, Odoms-Young A, Willis S, Baber K, Guzman JR. The application of focus group methodologies to community-based participatory research. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, eds. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2005:146–166.

- 64.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967.

- 65.Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA, Bernat DH, Sellers RM, Notaro PC. Racial identity, maternal support, and psychological distress among African American adolescents. Child Dev. 2002;73(4):1322–1336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmelke-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J Health Social Behav. 2003;44(3):302–317. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Pardo MS. Mexican American Women as Activists: Identity and Resistance in Two Los Angeles Communities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1998.

- 68.Farquhar S. Effects of the perceptions and observations of environmental stressors on health and well-being in residents of eastside and southwest Detroit, Michigan [Doctoral Dissertation]. Ann Arbor, Michigan: School of Public Health, University of Michigan; 2000.

- 69.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Strogatz DS, James SA. Social support and hypertension among blacks and whites in a rural, southern community. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(6):949–956. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez L. The many methods of religious coping: development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56(4):519–543. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Parker EA, Lichtenstein RL, Schulz AJ, et al. Disentangling measures of individual perceptions of community social dynamics: results of a community survey. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(4):462–486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Centers for Disease Control. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. 1994. Available at: http://www.cdc.gpv/brfss/questionnaires/english.htm.

- 74.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire. 1999. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/dls/nhanes.htm. Accessed June 8, 2004.

- 75.Wittchen H-U. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(1):57–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Geneva: WHO; 1991.