Abstract

An extensive study of teichoic acid biosynthesis in the model organism Bacillus subtilis has established teichoic acid polymers as essential components of the gram-positive cell wall. However, similar studies pertaining to therapeutically relevant organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus, are scarce. In this study we have carried out a meticulous examination of the dispensability of teichoic acid biosynthetic enzymes in S. aureus. By use of an allelic replacement methodology, we examined all facets of teichoic acid assembly, including intracellular polymer production and export. Using this approach we confirmed that the first-acting enzyme (TarO) was dispensable for growth, in contrast to dispensability studies in B. subtilis. Upon further characterization, we demonstrated that later-acting gene products (TarB, TarD, TarF, TarIJ, and TarH) responsible for polymer formation and export were essential for viability. We resolved this paradox by demonstrating that all of the apparently indispensable genes became dispensable in a tarO null genetic background. This work suggests a lethal gain-of-function mechanism where lesions beyond the initial step in wall teichoic acid biosynthesis render S. aureus nonviable. This discovery poses questions regarding the conventional understanding of essential gene sets, garnered through single-gene knockout experiments in bacteria and higher organisms, and points to a novel drug development strategy targeting late steps in teichoic acid synthesis for the infectious pathogen S. aureus.

The bacterial cell wall is composed of polymers of carbohydrate and amino acids, present as a rigid, cross-linked structure, termed peptidoglycan, which plays a critical role in bacterial functions including growth, division, maintenance of cell shape, and protection from osmotic lysis (18). While the walls of gram-negative bacteria are composed primarily of peptidoglycan, those of gram-positive bacteria are more substantial and contain, in addition, large amounts of wall teichoic acid, an anionic polyol phosphate polymer that is covalently attached to peptidoglycan. Despite making up a significant portion of the gram-positive cell wall, the precise function of teichoic acid remains elusive. Indeed, a large body of evidence assembled for the model gram-positive Bacillus subtilis has established that the biosynthetic genes for wall teichoic acid biosynthesis are indispensable in that organism. Conversely, Weidenmaier et al. recently published a report on a mutant in Staphylococcus aureus that was apparently devoid of wall teichoic acid (38).

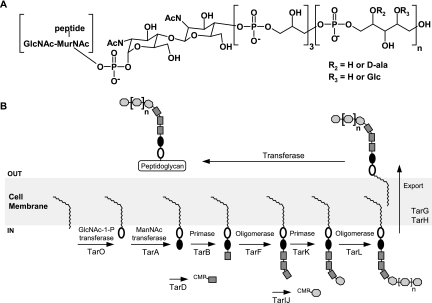

An analysis of the gene clusters for the synthesis of teichoic acid in B. subtilis strains 168 and W23, along with the benefit of many years of physiological, genetic, biochemical, and analytical work on wall teichoic acids, some in S. aureus, provided a rational basis for proposing functional roles for most of the gene products (7, 27, 28, 34). The major wall teichoic acids of the model gram-positive B. subtilis strains 168 and W23 are linear 1,3- and 1,5-linked poly(glycerol phosphate) and poly(ribitol phosphate), respectively. The poly(ribitol phosphate) polymer of B. subtilis W23 is also common to S. aureus. Figure 1 summarizes our understanding with a model for the biogenesis of poly(ribitol phosphate) wall teichoic acid in S. aureus. Teichoic acid biosynthesis begins with the formation of an undecaprenyl-pyrophosphoryl disaccharide on the cytoplasmic face of the cell membrane through the successive action of proteins TarO (N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase) and TarA (N-acetylmannosamine transferase). Subsequently a primase (TarB) and oligomerase (TarF) are believed to add a trimer of 1,3-linked glycerol-3-phosphate units to the 4-hydroxyl of N-acetylmannosamine. Glycerol-3-phosphate is provided by the action of TarD in an activated form, CDP-glycerol. Analogously, TarK and TarL have been proposed to prime and polymerize, respectively, a 1,5-linked polymer (∼30 units) of ribitol-5-phosphate on the terminal hydroxyl of the trimer of glycerol phosphate. TarIJ provides activated ribitol-5-phosphate in the form of CDP-ribitol. Intracellular synthesis of the complete polymer is thought to be followed by extrusion by TarGH, an ABC transporter, before transfer to the 6-hydroxyl of N-acetylmuramic acid moiety of peptidoglycan by an unknown transferase.

FIG. 1.

Proposed scheme for teichoic acid synthesis in S. aureus. (A) The chemical structure for the completed polymer covalently bound to N-acetylmuramic acid is depicted. The repeating ribitol-5-phosphate polymer is often replaced by d-alanine or glucose (R2 and R3). (B) S. aureus teichoic acid comprises a polymer composed of a disaccharide containing N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate (filled oval) and N-acetylmannosamine (open oval), 3 units of glycerol-3-phosphate (square), and ∼30 repeating ribitol-5-phosphate (octagon) units. These polymers are synthesized in a stepwise manner on the cytoplasmic face of the cell membrane onto undecaprenyl-phosphate (wavy line). Following synthesis, the entire polymer is exported out of the cell and attached to N-acetylmuramic acid of peptidoglycan.

The first evidence of an essential role for wall teichoic acid came from temperature-sensitive mutants isolated in B. subtilis 168, created through chemical mutagenesis, that mapped to the poly(glycerol phosphate) teichoic acid gene cluster (tag genes) (9, 10, 30). More recently, a xylose-induced expression system was used to facilitate the construction of precise deletions of teichoic acid synthetic genes in B. subtilis with complementing copies of the target genes ectopically integrated into the chromosome and subject to tight control of the xylose regulon (5, 6). The resulting strains were used to study the impact of controlled depletion of Tag gene products in a defined genetic background and at a physiologically relevant temperature. All the mutants showed lethal phenotypes that were fully rescued through induction of the complementing copy of the targeted gene. In all cases, depletion of teichoic acid biosynthetic genes resulted in a transition from rod-shape to bloated spheres, followed by division defects typified by aberrant septal localization, partial septation, septal curvature, thickening of the cell wall, and, ultimately, cell lysis. Thus, with the exception of tagA (the N-acetylmannosamine transferase, an orthologue of S. aureus tarA), all of the genes responsible for biosynthesis of the main chain of teichoic acid in B. subtilis 168 have been tested to date for dispensability. Each gene, including tagO (N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase, an orthologue of S. aureus tarO), has been shown to be indispensable for growth in B. subtilis 168 (5, 6, 23, 35).

Here, we report a comprehensive investigation of the dispensability of teichoic acid biosynthetic genes in S. aureus using a novel allelic replacement methodology. Our findings challenge the emerging doctrine of teichoic acid essentiality in gram-positive bacteria. We have confirmed that the gene encoding the first step of the pathway, tarO, is readily dispensable in S. aureus and that its deletion results in a strain lacking wall teichoic acid. Surprisingly, genes coding for subsequent biosynthetic steps in the pathway, tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ and tarH, resisted deletion and thus show an essential phenotype. This paradox of apparent indispensability of late-acting genes in an otherwise nonessential pathway was resolved with a systematic construction of double mutants. All of the late-acting genes became dispensable in a strain of S. aureus that lacked tarO. These surprising findings point to a mechanism for indispensability in late-acting teichoic acid biosynthetic genes, where a lethal gain of function results from a lesion in late-acting steps of the teichoic acid biogenesis pathway. The work has broad implications for our understanding of essential gene sets, gleaned through single-gene dispensability studies, of bacteria and higher organisms. These findings likewise point to a novel and exploitable drug development strategy targeting later steps in teichoic synthesis in S. aureus, an infectious pathogen of menacing renown in the clinic and in the community (14, 32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Cloning was performed in Escherichia coli DH5α (Promega) or Novablue (Novagen) strains grown in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C. All S. aureus strains, described in Table 1, were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) at 37°C. For selection in E. coli, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) were used. In S. aureus, kanamycin (Kan; 20 μg/ml), erythromycin (Erm; 10 μg/ml), spectinomycin (Spec; 300 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (Chl; 60 μg/ml), sucrose (5%, wt/vol), and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 0.4 mM) were used.

TABLE 1.

S. aureus strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and descriptiona | Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus strains | ||

| RN4220 | Restriction-deficient host | 21 |

| CYL316 | RN4220 derivative, recipient strain for plasmid pCL84 | 24 |

| SA178RI | CYL316 containing T7 polymerase, Tetr) | This study |

| tar gene integrantsb | ||

| EBII1 | SA178RI tarF (SACOL0239)::pSAKO-ΔtarF (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| EBII2 | SA178RI tarB (SACOL0696)::pSAKO-ΔtarB (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| EBII3 | SA178RI tarD (SACOL0698)::pSAKO-ΔtarD (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| EBII4 | SA178RI tarH (SACOL0694)::pSAKO-ΔtarH (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| EBII29 | SA178RI tarO (SACOL0810)::pSAKO-ΔtarO (Specr Kanr) | This study |

| EBII43 | SA178RI tarIJ (SACOL0240/0241)::pSAKO-ΔtarIJ (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| Uncomplemented deletion, EBII44 | SA178RI tarO::spec (Specr Kans) | This study |

| Complemented deletions | ||

| EBII5 | tarF::Erm pG164-tarF | This study |

| EBII6 | tarB::Erm pG164-tarB | This study |

| EBII7 | tarD::Erm pG164-tarD | This study |

| EBII8 | tarH::Erm pG164-tarH | This study |

| EBII53 | tarO::Spec pG164-tarO | This study |

| EBII56 | tarIJ::Erm pG164-tarIJ | This study |

| Complemented tar gene integrants | ||

| EBII9 | EBII2 pG164-tarB | This study |

| EBII10 | EBII4 pG164-tarH | This study |

| EBII15 | EBII3 pG164-tarD | This study |

| EBII27 | EBII1 pG164-tarF | This study |

| EBII50 | EBII43 pG164-tarIJ | This study |

| tar gene integrants in ΔtarO background | ||

| EBII35 | EBII2 tarO::Spec | This study |

| EBII36 | EBII3 tarO::Spec | This study |

| EBII37 | EBII1 tarO::Spec | This study |

| EBII38 | EBII4 tarO::Spec | This study |

| EBII46 | EBII43 tarO::Spec | This study |

| Double gene deletions | ||

| EBII47 | SA178RI tarO::Spec tarIJ::Erm | This study |

| EBII67 | SA178RI tarO::Spec tarB::Erm | This study |

| EBII68 | SA178RI tarO::Spec tarD::Erm | This study |

| EBII70 | SA178RI tarO::Spec tarF::Erm | This study |

| EBII71 | SA178RI tarO::Spec tarH::Erm | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCL84 | S. aureus integration vector (Tetr) | 24 |

| pACYC184 | E. coli plasmid containing p15A origin of replication | NEB |

| pQF50 | Source of MCS and trpA transcription terminator for pSAKO | 15 |

| pUS19 | pUC19 derivative containing Specr cassette | 4 |

| pDG1664 | Source for Ermr cassette | 17 |

| pSAKO | E. coli replicating vector containing sacB[BamP]W29 and Kanr cassette | This study |

| pUC19 | Source for pUC origin and bla gene for selection and replication in E. coli (Ampr) | NEB |

| pSK265 | Source of pC194 origin and CAT gene for selection and replication in S. aureus (Chlr) | 20 |

| pG164 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector for T7 based protein expression (Ampr Chlr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarO | Plasmid for single integration into tarO flank (Specr Kanr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarB | Plasmid for single integration into tarB flank (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarD | Plasmid for single integration into tarD flank (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarF | Plasmid for single integration into tarF flank (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarIJ | Plasmid for single integration into tarIJ flank (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| pSAKO-ΔtarH | Plasmid for single integration into tarH flank (Ermr Kanr) | This study |

| pG164-tarO | PG164 containing wild-type tarO from S. aureus | This study |

| pG164-tarB | PG164 containing wild-type tarB from S. aureus | This study |

| pG164-tarD | PG164 containing wild-type tarD from S. aureus | This study |

| pG164-tarF | PG164 containing wild-type tarF from S. aureus | This study |

| pG164-tarIJ | PG164 containing wild-type tarIJ from S. aureus | This study |

| pG164-tarH | PG164 containing wild-type tarH from S. aureus | This study |

Spec, spectinomycin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Tet, tetracycline; Erm, erythromycin; Kan, kanamycin; Amp, ampicillin.

S. aureus COL gene identification is given in brackets.

S. aureus teichoic acid biosynthesis sequences were identified by using BLAST analysis and comparing the protein sequences of B. subtilis 168 and W23 taken from the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nih.gov) against the S. aureus COL genome obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research database (www.tigr.org). S. aureus COL gene identifications can be found in Table 1 next to the corresponding tar designations for each gene studied.

Chromosomal manipulation of S. aureus.

DNA manipulations were performed using both transformation and transduction. Transformation was accomplished through standard electroporation procedures (25). Transductions were performed using bacteriophage 80α and standard protocols (29).

Generation of S. aureus SA178RI.

The S. aureus expression strain SA178RI was constructed via integrative transformation into the strain CYL316, a derivative of RN4220. The T7 polymerase gene from λDE3 was placed under the control of the gram-positive promoter Pspac and cloned upstream of the lacI repressor driven by the constitutive promoter Ppen to generate the expression cassette. Two lac operator sequences were introduced into the Pspac promoter upstream of the ribosome binding site as well as a trpA terminator upstream of the promoter region. The trpA term-Pspac/T7-Ppen/lacI cassette was cloned into the integration vector pCL84 and electroporated into CYL316. Tetracycline-resistant and lipase-negative colonies were the result of successful integration of the cassette into the geh locus.

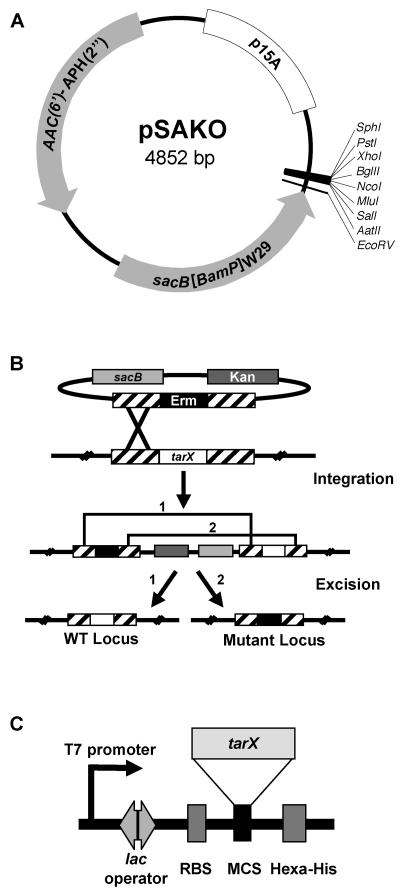

Construction of pSAKO, an S. aureus gene deletion plasmid.

pSAKO is an S. aureus suicide vector utilized to disrupt chromosomal copies of S. aureus genes. pSAKO has a gram-negative p15A origin of replication subcloned from pACYC184, making it nonreplicative in S. aureus. It has a multiple cloning site (MCS) and a trpA transcriptional terminator cloned from pQF50. It also has the gene encoding the bifunctional enzyme AAC(6′)-APH(2"), conferring aminoglycoside resistance for selection in both E. coli and S. aureus, which was cloned as a PCR product from S. aureus genomic DNA (16). pSAKO also has a copy of the mutated levansucrase gene, sacB[BamP]W29 (8), which confers sucrose-induced lethality in S. aureus, allowing for counterselection.

Construction of pG164, an S. aureus complementation vector.

pG164 is an E. coli and S. aureus shuttle vector constructed by fusing pUC19 and pSK265. The vector has both a pUC and a pC194 origin for replication in gram-negative and -positive bacteria, respectively. The expression cassette in pG164 is comprised of a T7 promoter into which a lac operator has been introduced to enhance regulation in the absence of inducer, as well as a gram-positive optimal ribosome binding site, an MCS, and a C-terminal six-histidine tag. pG164 also has a copy of the lacI repressor regulated by the constitutive promoter Ppen to reduce background expression in the absence of induction.

Creation of gene-specific deletion plasmids.

Primer sequences are found in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All PCRs were performed using Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) or a Roche High-Fidelity PCR System. The spectinomycin and erythromycin cassettes were PCR amplified using SpecF-SpecR and ErmF-ErmR, respectively. For each gene, the left and right flanks were independently amplified from the SA178RI chromosome using gene-specific primers sets A-B and C-D, respectively. Primers B and C contain regions complementary to the resistance cassette to allow binding. A final PCR using gene-specific primers A-D was performed using the resistance cassette and both left and right flanks as a template. The resulting product was purified and ligated into the XhoI site of pSAKO.

Creation of integrants in tarO, tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH.

SA178RI was independently transformed with gene-specific pSAKO integration plasmids (Table 1). Integrants were selected on MH agar (MHA) supplemented with kanamycin and spectinomycin or erythromycin. Strains generated were confirmed by PCR.

Testing for gene essentiality.

Integrants (EBII1, EBII2, EBII3, EBII4, EBII29, and EBII43) were plated on MHA containing sucrose. A total of 100 colonies from each strain were selected and passaged twice more onto MHA with sucrose. Each colony was then patched onto MHA containing kanamycin, MHA containing erythromycin or spectinomycin, and MHA alone to determine phenotype. For strains in which mutants could not be generated, the same procedure was performed on complemented integrants (EBII9, EBII10, EBII15, EBII27, and EBII50). In addition to the above antibiotics, this medium was supplemented with chloramphenicol and IPTG. Finally, the dispensability of tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH in a ΔtarO background was determined using integrants EBII35, EBII36, EBII37, EBII46, and EBII38 as described above. The growth medium contained spectinomycin through all steps in the procedure. The phenotype of each colony was determined, and the data are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Allelic replacement for testing gene dispensability

| Strain | Phenotype (no. of colonies)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Nonexcisant | Mutant | |

| No complementation | |||

| tarO | 57 | 1 | 42 |

| tarB | 91 | 9 | 0 |

| tarD | 94 | 6 | 0 |

| tarF | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| tarIJ | 96 | 4 | 0 |

| tarH | 98 | 2 | 0 |

| Complemented | |||

| tarB | 75 | 0 | 25 |

| tarD | 44 | 0 | 56 |

| tarF | 36 | 0 | 64 |

| tarIJ | 76 | 1 | 23 |

| tarH | 58 | 0 | 42 |

| ΔtarO background | |||

| tarB | 64 | 2 | 34 |

| tarD | 36 | 0 | 64 |

| tarF | 29 | 1 | 70 |

| tarIJ | 68 | 0 | 32 |

| tarH | 52 | 0 | 48 |

A total of 100 colonies of each strain were tested.

Creation of ΔtarO and ΔtarO pG164-tarO.

EBII29 was passaged three times on MHA containing sucrose and spectinomycin to generate a tarO deletion (EBII44). EBII44 was transformed with pG164-tarO to generate a complemented ΔtarO strain (EBII53).

Creation of tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH integrants in a ΔtarO background.

For the generation of the tarIJ integrant in the ΔtarO background, pSAKO-ΔtarIJ was transformed into EBII44 and selected for on MHA containing erythromycin and kanamycin to generate EBII46. For all other clones, EBII53 was used to generate bacteriophage 80α lysate. This lysate was used to transduce each integrant (EBII1, EBII2, EBII3, EBII4, and EBII29) and selected on MHA containing spectinomycin and kanamycin. This allowed the movement of the tarO deletion, marked with spectinomycin, into each single integrant.

Creation of double-gene deletions.

Strains EBII35, EBII36, EBII37, EBII38, and EBII46 were plated for three successive rounds on MHA containing spectinomycin, erythromycin, and sucrose to generate double mutants.

PCR verification of single integrant and deletion strains.

All single integrant and deletion strains were verified by PCR analysis (data not shown). For deletion strains, analysis was performed using a drug cassette-specific primer and primers designed to anneal to sequences of the flanking regions. For single integrant strains, analysis was performed using a drug cassette-specific primer and primers designed to anneal either to the flanking regions or to sequences in pSAKO. In all cases, PCR analysis was performed for both the upstream and downstream sequences flanking the insertion.

Cell wall phosphate content determination.

Strains were grown overnight in 5 ml of MHB and used to inoculate 100 ml of fresh MHB and grown at 37°C overnight to saturation. Cell wall isolation and phosphate content determination were carried out as described previously (6). Briefly, cell wall was extracted by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate (26), DNase, and RNase and trypsin treated (22) and mineralized (2). Wall phosphate content was assayed by absorbance using KH2PO4 as a standard (12).

RESULTS

Testing gene dispensability in S. aureus with pSAKO.

While the genetic tools for studies of gene dispensability in B. subtilis are relatively robust, those for S. aureus are considerably less definitive. In the work reported here we developed a novel plasmid (pSAKO) for allelic replacement in S. aureus that facilitates testing gene essentiality (outlined in Fig. 2). Plasmid pSAKO encodes a kanamycin resistance marker [AAC(6′)-APH(2")], allowing for selection in both E. coli and S. aureus. A key feature of this plasmid is a counter-selectable marker, the B. subtilis SacB variant (sacB[BamP]W29) that is impaired for secretion and produces a product toxic to S. aureus in the presence of sucrose (8). The flanks (∼1,000 bp) surrounding the gene targeted for deletion are cloned into the polylinker of pSAKO along with an intervening drug marker (Erm). Transformation and selection result in single recombinants containing a tandem duplication of the targeted locus consisting of wild-type and mutant copies. Subsequent plating on sucrose selects for loss of the plasmid sequences through two possible excision events. If the gene is dispensable, both mutant (Erm resistant and Kan sensitive) and wild-type (Erm sensitive and Kan sensitive) clones will be generated. In the case of an essential gene, only the wild-type allele will be isolated among the resulting clones. The strength of this methodology is in a passive approach to the isolation of excisants and subsequent evaluation of resistance profiles of the resulting clones to reveal frequencies at which the organism can dispense with the targeted gene.

FIG. 2.

A novel genetic strategy for testing dispensability in S. aureus. (A) pSAKO contains a gram-negative p15A replication origin that allows replication in E. coli but not in S. aureus. Selection in both E. coli and S. aureus is accomplished using the kanamycin resistance cassette, AAC(2′)-APH(6"), while a mutant form of SacB (sacB[BamP]W29) permits counterselection. Unique restriction sites found within the MCS are highlighted on the outside of the plasmid. (B) Integration of pSAKO encoding kanamycin resistance and containing an erythromycin resistance cassette, the latter flanked by ∼1,000 bp of chromosomal sequences upstream and downstream of the targeted gene (tarX), occurs through single recombination. Selection for excision of the plasmid sequence is accomplished using sacB[BamP]W29 (sacB) (8) on medium containing sucrose. Excision results in restoration of the wild-type (WT) locus or generation of a mutant locus. (C) The expression cassette located on pG164 was used to express the complementing copy of the gene of interest (tarX) cloned into the MCS. Protein expression was driven by a T7 promoter controlled by a chromosomally integrated T7 polymerase induced by IPTG.

Investigating teichoic acid biosynthetic gene dispensability in S. aureus.

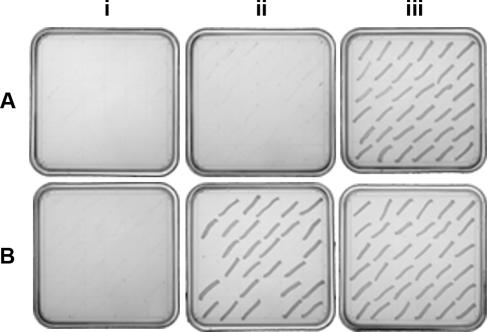

Plasmid pSAKO was used to test the dispensability of each step of S. aureus teichoic acid biosynthesis, including disaccharide formation (tarO), glycerol phosphate oligomerization (tarD, tarB, and tarF), ribitol phosphate polymerization (tarIJ), and teichoic acid export (tarH). A sample of the data for 36 clones obtained for tarD is shown in Fig. 3A. Here, all integrants excised under counterselection produced Kan-sensitive colonies, of which none were Erm resistant, indicating the absence of a propensity to generate viable deletions in tarD. As a positive control, selection for excisants was also done with a plasmid-encoded copy of tarD provided in trans (Fig. 3B). Here, excision of 28 of 36 integrants produced a deletion of tarD (Erm resistant) while excision of 8 others restored the wild-type locus. The ability to produce a deletion in tarD in the presence of a complementing copy confirmed that our inability to generate mutants in the absence of complementation was due to the indispensable nature of the target gene and not a systematic inability to generate a mutant excisant. Thus, these data were consistent with an essential phenotype for tarD, demonstrating that our deletion strategy could be used to distinguish between dispensable and indispensable genes.

FIG. 3.

Dispensability analysis of S. aureus tarD. Integrants targeting tarD (EBII3 and EBII15) were subjected to selection for excisants on MHA containing sucrose (EBII3) (A) and MHA containing chloramphenicol, IPTG, and sucrose (EBII15) (B). The phenotypic outcome of selection was revealed in the resistance profile of three test plates containing (i) kanamycin, (ii) erythromycin, and (iii) no antibiotic.

Table 2 details the outcome of counterselection on sucrose for 100 integrants in each targeted gene. Each integrant was examined for excision of the plasmid and replacement of the targeted gene with a resistance cassette. With a low frequency, some colonies failed to excise the plasmid, remaining single integrants, and were identified as nonexcisants. Gene tarO showed roughly equal propensity to generate either mutant or wild type on excision in the absence of complementation, indicating that tarO was dispensable in a wild-type background, which is consistent with a previous study (38). Also consistent with the previous study, the growth of the tarO mutant was not significantly impaired compared to wild type (data not shown). Surprisingly, in contrast to tarO, integrants targeted to tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH consistently failed to produce a mutant phenotype. All excised the plasmid sequence to leave the wild-type locus in the absence of complementation. When a complementing copy of each gene was supplied in trans, integrants resolved to produce both wild-type and mutant alleles with roughly equal propensity. Thus, the data are consistent with an essential phenotype for these late-acting genes, all of which carry out biosynthetic reactions after the formation of undecaprenyl-pyrophosphoryl-disaccharide.

The requirement for TarO cannot be bypassed.

One explanation for this paradox is that cells may be making teichoic acid in the absence of tarO, perhaps through the use of a redundant enzyme to transfer N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate to undecaprenyl-phosphate or by remodeling the teichoic acid polymer to exclude the need for the N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate moiety. This would be consistent with the conventional understanding in B. subtilis that teichoic acid polymers are an essential component of the cell wall in S. aureus. To address this we endeavored to test the dispensability of the late-acting genes (tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH) in the ΔtarO genetic background. Again, 100 integrants targeting the late-acting genes in the ΔtarO strain were characterized following counterselection (Table 2). In all cases, excision generated both wild-type and mutant alleles with approximately equal propensity. Thus, the late-acting genes (tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH) became nonessential in the absence of tarO, a finding inconsistent with the possibility that TarO function could be bypassed in any fashion. Indeed, we confirmed that the cell wall phosphate content was vastly reduced in the ΔtarO mutant relative to the parent strain (0.0069 ± 0.0003 and 0.48 ± 0.05 μmol phosphate/mg of cell wall, respectively) and that provision of plasmid-encoded tarO in trans could correct the defect in this mutant (0.37 ± 0.02 μmol phosphate/mg of cell wall). Accordingly, our characterization of the teichoic acid content of the tarO mutant was in accord with the previous study indicating that the viable tarO deletion mutant lacked teichoic acid (38).

DISCUSSION

In the work reported here we have embarked on a systematic examination of the dispensability of genes coding for poly(ribitol phosphate) teichoic acid in S. aureus with a novel allelic replacement vector pSAKO. Paradoxically, while wall teichoic acid polymers appeared to be dispensable for viability in vitro, several late-acting genes in the pathway for teichoic acid synthesis were indispensable. This apparent contradiction was resolved with the demonstration that late-acting genes became dispensable in a strain that lacked tarO, coding for the first step in the pathway. The suppression of an essential phenotype associated with the late-acting genes in the pathway (tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH) by a deletion in the first step (tarO) is a remarkable and intriguing finding. This ability to suppress the lethal effects of gene deletion by a secondary site deletion is not an exceptional case. The best-characterized and most simplistic examples are with the toxin-antitoxin gene pairs of bacteria (1). Here, deletion of the antitoxin gene leads to cell death, unless there is a compensating deletion of the cognate toxin gene. Perhaps most interestingly, our observations are also echoed by some curious reports in systems involving bacterial exopolysaccharide synthesis. Studies of succinoglycan biosynthesis in Rhizobium meliloti revealed that a mutation in exoR, resulting in upregulation of the exo gene cluster, caused late-acting genes to become essential, while double mutants in exoR and early steps of this pathway were viable (31). Recently, Cuthbertson et al. showed that in E. coli O9a, the wzm-wzt ABC transporter for polymannan O-antegenic polysaccharide export was only dispensable in a strain containing a secondary mutation preventing polymannan production (13). In the work reported here, we have discovered analogous genetic interactions that pervade an entire metabolic pathway.

Our observations regarding suppression of lethality within the teichoic acid biosynthetic pathway suggest a mechanism where a single mutation in late-acting steps leads to a lethal gain of function for the abbreviated pathway. The most parsimonious interpretation of our findings is that once teichoic acid production has commenced, it must be completed or else lethal intermediates accumulate. For example, the incomplete production of teichoic acid might cause an accumulation of toxic precursors, such as activated sugars or partially complete polymer, leading to cell death. Alternatively, a lesion in teichoic acid synthesis may interfere with the synthesis of some truly essential component of the cell, for example, by sequestering a shared building block. Apart from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine and undecaprenyl-phosphate, which are shared with peptidoglycan biosynthesis, teichoic acid synthesis uses building blocks that are exclusive to its own synthesis. Interestingly, work using isolated B. subtilis membranes demonstrated that inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis could occur by providing a soluble teichoic acid precursor, CDP-glycerol (3), suggesting a functional link between the assembly of these two major cell wall components. Along these lines, a failure to complete teichoic acid production could conceivably sequester the otherwise recycled undecaprenyl-phosphate molecule (36) upon which peptidoglycan is also built (19). Such a mechanism for lethality could surely be corrected by preventing the initiation of teichoic acid production with the loss of tarO. This explanation is further supported circumstantially by the phenotypes of conditional mutants in these metabolic pathways. Lesions in teichoic acid synthesis (5), peptidoglycan biogenesis (37), and isoprenoid biosynthesis (11), the latter pathway being responsible for undecaprenol production, all result in remarkably similar and profoundly altered cell morphology, as shown by electron microscopy examination.

The essential phenotypes of the five late-acting loci studied in this work (tarB, tarD, tarF, tarIJ, and tarH) suggest that all late-acting genes, at least from tarB onward, will be essential. The prediction, therefore, is that four additional genes (tarK, tarL, tarG, and the unknown transferase), and possibly tarA, will show an essential phenotype in S. aureus. The possibility of 10 apparently indispensable genes coding for the 11-step synthesis of a nonessential polymer in S. aureus challenges the conventional understanding of essential gene sets garnered through single-gene deletion experiments, at least in the laboratory setting.

The discovery of a lethal gain of function associated with lesions in the late steps of teichoic acid biosynthetic genes points to a novel therapeutic route to target the pathogen S. aureus. S. aureus is a major cause of hospital-acquired infection and has become increasingly difficult to treat due to resistance to multiple antibiotics including methicillin (33) and vancomycin (39). The work outlined here suggests that inhibition of late-acting enzymes in teichoic acid biosynthesis leads to cell death, possibly through a corrupting impact on cell wall peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Indeed, while a mutation of the first-acting gene, tarO, would be capable of suppressing the lethal inhibition of late-acting steps, Weidenmaier et al. have shown wall teichoic acid in S. aureus to be a key virulence determinant for infection (38). Thus, wall teichoic acid biosynthesis appears to be critical for growth in vivo and represents a pathway that is vulnerable to an extraordinary mechanism for lethality upon inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. E. Heinrichs for providing bacteriophage 80α.

This work was supported, in part, by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant (MOP-15496). M.A.D. and M.P.P. were funded by the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities. E.D.B. holds a Canada Research Chair in Microbial Biochemistry.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizenman, E., H. Engelberg-Kulka, and G. Glaser. 1996. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine [corrected] 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6059-6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames, B. N. 1966. Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 8:115-118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, R. G., H. Hussey, and J. Baddiley. 1972. The mechanism of wall synthesis in bacteria. The organization of enzymes and isoprenoid phosphates in the membrane. Biochem. J. 127:11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson, A. K., and W. G. Haldenwang. 1993. Regulation of sigma B levels and activity in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:2347-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhavsar, A. P., T. J. Beveridge, and E. D. Brown. 2001. Precise deletion of tagD and controlled depletion of its product, glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, leads to irregular morphology and lysis of Bacillus subtilis grown at physiological temperature. J. Bacteriol. 183:6688-6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhavsar, A. P., L. K. Erdman, J. W. Schertzer, and E. D. Brown. 2004. Teichoic acid is an essential polymer in Bacillus subtilis that is functionally distinct from teichuronic acid. J. Bacteriol. 186:7865-7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhavsar, A. P., R. Truant, and E. D. Brown. 2005. The TagB protein in Bacillus subtilis 168 is an intracellular peripheral membrane protein that can incorporate glycerol phosphate onto a membrane-bound acceptor in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 280:36691-36700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bramucci, M. G., and V. Nagarajan. 1996. Direct selection of cloned DNA in Bacillus subtilis based on sucrose-induced lethality. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3948-3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt, C., and D. Karamata. 1987. Thermosensitive Bacillus subtilis mutants which lyse at the non-permissive temperature. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:1159-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briehl, M., H. M. Pooley, and D. Karamata. 1989. Mutants of Bacillus subtilis 168 thermosensitive for growth and wall teichoic acid synthesis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:1325-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell, T. L., and E. D. Brown. 2002. Characterization of the depletion of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:5609-5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, P., T. Toribara, and H. Warner. 1956. Microdetermination of phosphorus. Anal. Chem. 18:1756-1758. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuthbertson, L., J. Powers, and C. Whitfield. 2005. The C-terminal domain of the nucleotide-binding domain protein Wzt determines substrate specificity in the ATP-binding cassette transporter for the lipopolysaccharide O-antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes O8 and O9a. J. Biol. Chem. 280:30310-30319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diekema, D. J., M. A. Pfaller, F. J. Schmitz, J. Smayevsky, J. Bell, R. N. Jones, and M. Beach. 2001. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2):S114-S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farinha, M. A., and A. M. Kropinski. 1990. Construction of broad-host-range plasmid vectors for easy visible selection and analysis of promoters. J. Bacteriol. 172:3496-3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freitas, F. I., E. Guedes-Stehling, and J. P. Siqueira-Junior. 1999. Resistance to gentamicin and related aminoglycosides in Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Brazil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29:197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 180:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock, I. C. 1997. Bacterial cell surface carbohydrates: structure and assembly. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25:183-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higashi, Y., J. L. Strominger, and C. C. Sweeley. 1967. Structure of a lipid intermediate in cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis: a derivative of a C55 isoprenoid alcohol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 57:1878-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, C. L., and S. A. Khan. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the enterotoxin B gene from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 166:29-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruyssen, F. J., W. R. de Boer, and J. T. Wouters. 1980. Effects of carbon source and growth rate on cell wall composition of Bacillus subtilis subsp. niger. J. Bacteriol. 144:238-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazarevic, V., and D. Karamata. 1995. The tagGH operon of Bacillus subtilis 168 encodes a two-component ABC transporter involved in the metabolism of two wall teichoic acids. Mol. Microbiol. 16:345-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, C. Y., S. L. Buranen, and Z. H. Ye. 1991. Construction of single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 103:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, J. C. 1995. Electrotransformation of staphylococci. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald, K. L., and T. J. Beveridge. 2002. Bactericidal effect of gentamicin-induced membrane vesicles derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 on gram-positive bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 48:810-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarre, W. W., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:174-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuhaus, F. C., and J. Baddiley. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:686-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pooley, H. M., F. X. Abellan, and D. Karamata. 1991. A conditional-lethal mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168 with a thermosensitive glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, an enzyme specific for the synthesis of the major wall teichoic acid. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:921-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reuber, T. L., and G. C. Walker. 1993. Biosynthesis of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Cell 74:269-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson, D. A., A. M. Kearns, A. Holmes, D. Morrison, H. Grundmann, G. Edwards, F. G. O'Brien, F. C. Tenover, L. K. McDougal, A. B. Monk, and M. C. Enright. 2005. Re-emergence of early pandemic Staphylococcus aureus as a community-acquired methicillin-resistant clone. Lancet 365:1256-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salgado, C. D., B. M. Farr, and D. P. Calfee. 2003. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schertzer, J. W., and E. D. Brown. 2003. Purified, recombinant TagF protein from Bacillus subtilis 168 catalyzes the polymerization of glycerol phosphate onto a membrane acceptor in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18002-18007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soldo, B., V. Lazarevic, and D. Karamata. 2002. tagO is involved in the synthesis of all anionic cell-wall polymers in Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology 148:2079-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Heijenoort, J. 2001. Recent advances in the formation of the bacterial peptidoglycan monomer unit. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18:503-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei, Y., T. Havasy, D. C. McPherson, and D. L. Popham. 2003. Rod shape determination by the Bacillus subtilis class B penicillin-binding proteins encoded by pbpA and pbpH. J. Bacteriol. 185:4717-4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weidenmaier, C., J. F. Kokai-Kun, S. A. Kristian, T. Chanturiya, H. Kalbacher, M. Gross, G. Nicholson, B. Neumeister, J. J. Mond, and A. Peschel. 2004. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10:243-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weigel, L. M., D. B. Clewell, S. R. Gill, N. C. Clark, L. K. McDougal, S. E. Flannagan, J. F. Kolonay, J. Shetty, G. E. Killgore, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 302:1569-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.