Abstract

Approximately one-third of the open reading frames encoded in the Sulfolobus solfataricus genome were differentially expressed within 5 min following an 80 to 90°C temperature shift at pH 4.0. This included many toxin-antitoxin loci and insertion elements, implicating a connection between genome plasticity and metabolic regulation in the early stages of stress response.

The ability to cope with environmental stress is essential to microorganisms (1, 34, 39), including those thriving in extreme environments relative to temperature (4, 10, 21, 28, 42, 45, 50, 52), pressure (9, 31, 35, 44, 51), ionic strength (47), acidity (30, 53), alkalinity (26), metals (15, 37), and radiation (25, 36, 43). Certain crenarchaea, such as members of the Sulfolobales, occupy niches that are biologically extreme in two respects: low pH and elevated temperature (19). Key to their physiological function is a transmembrane proton gradient that renders intracellular pH close to neutral. As such, maintaining cytosolic pH in the face of thermal stress-induced cellular damage involves complex genetic and metabolic strategies (40). To examine such mechanisms for extreme thermoacidophiles at supraoptimal temperatures, the heat shock response of Sulfolobus solfataricus (49, 55) was studied using genome-wide transcriptional response.

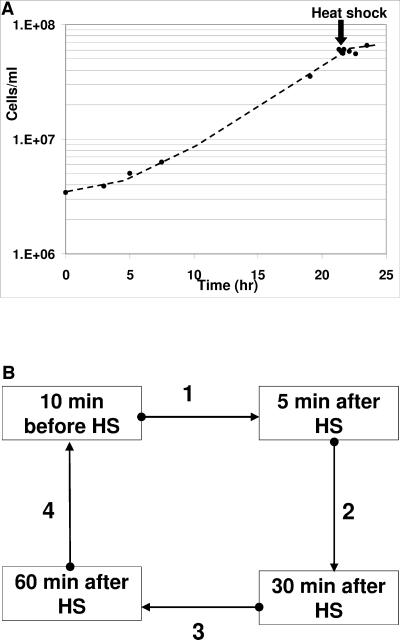

A whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray for Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 (DSMZ, Germany) was developed (49). Probes were designed in OligoArray 2.0 (46), custom synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA), and printed onto arrays following protocols previously developed for other hyperthermophiles (14, 20, 50); five replicates per probe were spotted on each array to fortify statistical analysis. S. solfataricus was routinely grown at 80°C and pH 4.0 on DSMZ 182 medium; cells were enumerated using epifluorescence microscopy with acridine orange stain (13). The heat shock time course experiment was carried out as described in the legend for Fig. 1A. RNA was extracted from chilled culture samples (12). cDNA synthesis, microarray hybridizations (Fig. 1B), and data collection were performed as described previously (12), with minor adjustments for long oligonucleotide platforms. Data from each experiment were analyzed with SAS 9.0 (SAS, Cary, NC) (42), using a mixed linear analysis of variance model (54). A ±2.0-fold change (FC) or higher defined differential expression.

FIG. 1.

Cell density of S. solfataricus before and during HS (A) and experimental design used for microarray hybridizations (B). The experiment was carried out with a modified 3-liter glass fermentor (Applikon, Schiedam, The Netherlands). The culture was shifted from 80 to 90°C (∼8 min) at mid-exponential phase and maintained at 90°C ± 1°C for 2 h. Samples were taken 10 min before starting the temperature shift and then 5, 30, and 60 min after reaching 90°C. cDNA samples were then hybridized in a four-slide loop design (B). Dots and arrowheads represent cyanine 3- and cyanine 5-labeled samples, respectively.

Transcriptional response to heat stress.

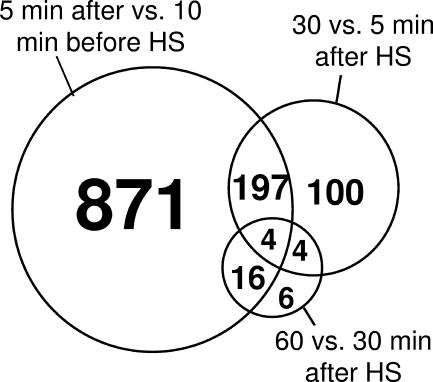

When S. solfataricus was shifted from 80 to 90°C at pH 4.0, approximately one-third of the genome responded (1,088 genes, 551 up/537 down) within 5 min after the culture reached 90°C. Differential expression was less pronounced after this initial period; ∼300 genes (161 up/144 down) changed between 5 and 30 min, and only 30 genes (18 up/12 down) changed between 30 and 60 min (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Table 2 lists selected heat shock (HS)-responsive genes involved in basic metabolic functions and regulation. S. solfataricus relies on HSP20 family small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) (27), the thermosome/rosettasome (21) for protein folding, and the proteasome (33), several HtpX homologs (48), and various other proteases for protein turnover. Here, both sHSPs responded within 5 min after temperature shift (Table 3). In contrast, the α and β thermosome subunits were not HS responsive; this was expected given their already high expression levels under normal conditions (23). The γ thermosome subunit expression, however, was significantly lower than those for the α and β subunits before stress and was further down-regulated during the course of HS response. This is consistent with previous reports showing a shift in thermosome composition from 1α:1β:1γ to a heat-stressed ratio of 2α:1β:0γ (22). Genes encoding HtpX proteases and proteasome subunits (α, β1, and β2) were not affected by HS, and the proteasome-associated nucleotidase was down-regulated significantly. Genes encoding subunits of the exosome, which is involved in mRNA polyadenylation and degradation (41), were strongly repressed immediately after HS (Table 3). Three open reading frames (ORFs) encoding Sso7d DNA binding proteins were up-regulated upon heat shock, consistent with their role in maintaining negative supercoiling of DNA during thermal stress (29). Many transcriptional regulators were strongly induced by thermal stress (Table 2), consistent with widespread changes in the S. solfataricus transcriptome. The most significant changes were for putative TetR (SSO2506, +24.3 FC) and GntR family repressors (SSO1589, +32.0 FC); strong induction of both within 5 min indicates an important role in early HS response.

TABLE 1.

Summary of differentially transcribed ORFs in S. solfataricus under heat shock

| ORFs | No. of responsive genes by time point comparison

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 vs −10 min | 30 vs 5 min | 60 vs 30 min | 60 vs −10 min | |

| Up-regulated | 551a | 161 | 18 | 489 |

| Down-regulated | 537 | 144 | 12 | 391 |

| Total | 1,088 | 305 | 30 | 880 |

Of which 205 genes are IS elements, transposases, resolvases, and related sequences.

FIG. 2.

Venn diagram representing the overlap of differential gene expression between time point comparisons for heat shock-responsive genes. Note that the numbers in each circle are additive.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of selected heat shock-responsive genes for S. solfataricus cultured at pH 4.0 and 80°C and shifted to 90°C

| Metabolic pathway/function | ORF, gene name or description | Change (n-fold) | Time point comparison (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA metabolism | |||

| DNA polymerase II | SSO1459 | −4.0 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO8124 | −12.1 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Recombinases (putative) | SSO2452 recA | +3.7 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO1994 | +3.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Double-stranded DNA break and recombination | SSO0264 putative recB | +2.0 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO0250 radA | +2.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Partial exonuclease | SSO2250 rad32 | +2.8 | 30 vs 5 |

| SSO2373 | +2.1 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Damage-inducible DNA repair polymerase | SSO2448 dinP | +3.5 | 60 vs −10 |

| Putative DNA ligase | SSO2734 | +5.3 | 5 vs −10 |

| Putative endonuclease | SSO3029 | +2.8 | 60 vs −10 |

| MutT-like protein | SSO3167 | +3.2 | 60 vs −10 |

| Transcription and DNA modification | SSO0265 | +4.3 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO0266, tfe | +5.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO0267 | +4.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO0269, hflX | +2.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SS0270 | +3.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| mRNA production | |||

| RNA polymerase | SSO0223 rpoA2 | −5.8/+3.4 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 |

| SSO0225 rpoA1 | −2.2/+1.4 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0227 rpoB1 | −7.1/+2.5 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO3254 rpoB2 | −4.8/+3.5 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0071 rpoD | −12.6/+2.9 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| Energy metabolism | |||

| NADH dehydrogenase | SSO0323 nuoC | −2.1/+3.0 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 |

| SSO0324 nuoD | −9.2/+5.6 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0325 nuoH | −11.3/+4.0 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0326, nuoI | −10.6/+5.3 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0327, nuoJ | −6.7/+2.8 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0328, nuoL | −6.5/+2.0 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| SSO0329, nuoN | −7.0/+1.9 | 5 vs −10/30 vs 5 | |

| Flavoproteins | SSO0584 | +5.7 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO2348 | −2.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2353 | −3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2762 | +2.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2763 | +2.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2776 | +2.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2817 | −5.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2819 | −2.8 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Terminal oxidase | SSO0044 doxB | −4.9 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO0045 doxC | −4.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO5098 doxE | −2.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Miscellaneous redox proteins | SSO0368 trxA-1 | +2.6 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO2232 trxA-2 | +2.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2416 | +2.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2765 | +3.2 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Cofactor biosynthesis | |||

| Cobalamin | SSO2305, cbiD | −5.3 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO2296 cbiE | −2.1 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2299 cbiF | −3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2297 cbiG-like | −3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2306 cbiH | −3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2301 cbiL | +3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2303 cbiT | +3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| MGDa | SSO0770 moaC | +2.0 | 30 vs 5 |

| SSO0675 mobB | +3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO0676 | +2.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2365 moeA | +2.1 | 30 vs 5 | |

| Lipids | |||

| Acetyl coenzyme A C-acetyltransferase | SSO0534 acaB-1 | −6.5 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO2062 acaB-3 | −2.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2697 acaB-8 | −3.2 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2377 aca-4 | +3.7 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2496 acaB-5 | +3.5 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2508 acaB-6 | +2.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO3113 acaB-10 | −4.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | SSO1030 fabG-2 | −3.0 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO fabG-3 | +4.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2205 fabG-4 | −2.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2276 fabG-5 | −2.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2500 fabG-7 | +2.8 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO3004 fabG-9 | +3.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO 3114 fabG-10 | −3.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Transporters | |||

| Iron | SSO0485 | −4.3 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO0486 | −4.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO0487 | −4.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Cobalt | SSO1892 | −4.9 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO1893 | −4.9 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO1894 | 4.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Phosphate | SSO0489 | −2.1 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO0490 | −2.5 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Sulfate | SSO2469 | −4.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| Amino acids | SSO0786 | −2.3 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO1009 | −2.1 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1069 | −6.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1173 | −3.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2726 | −3.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2728 | −2.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Peptides | SSO3047 | −2.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO3048 | −2.1 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Oligonucleotides/dipeptides | SSO1274 | −16.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO1275 | −14.9 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1276 oppD | −7.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1277 oppF | −8 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1281 | −2.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1282 oppD | −5.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1283 | −6.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Arabinose | SSO3066 | −5.6 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO3067 | −3.5 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO3069 | −2.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Glucose | SSO2848 | −3.7 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO2849 | −4.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2850 | −7.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Maltose | SSO1000 | −3.5 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO1170 | −3.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO3053 | −2.5 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Drug resistance/efflux | SSO2035 | +2.0 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO2135 | +4.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2137 | +3.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2228 | +5.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2704 | +2.8 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO3012 | +4.3 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Transcriptional regulators | |||

| TetR family repressor | SSO2506 | +24.3 | 5 vs −10 |

| GntR family repressors | SSO1255 | +4.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO1589 | +32.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| MarR/Lrs14 family repressors | SSO0048 | +3.2 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO0458 | +4.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1082 | +4.9 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1108 | +4.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO1110 | +3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2138 | +3.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2897 | +6.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO3242 | −10.6 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Miscellaneous regulators | SSO0200 | −2.6 | 60 vs −10 |

| SSO0239 | −3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO0618 | +9.1 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO0669 | +2.1 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO1952 | −3.5 | 60 vs −10 | |

| SSO2131 | +2.5 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO5522 | +3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO10340 | +2.8 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2827 | +4.0 | 5 vs −10 |

MGD, molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of HS response of stress-related proteins in S. solfataricusa

| Category | ORF, gene name (gene symbol) | Change (n-fold) | Time point comparison (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaperones, HSPs and chromatin proteins | |||

| sHSP | SSO2427 | +2.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO2603 | +3.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| HtpX homolog | SSO1859 | NC | |

| SSO2694 | NC | ||

| SSO3231 | NC | ||

| USP family | SSO0529 | −2.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO1865 | +3.7 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO2778 | +3.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO3183 | +2.0 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Thermosome | SSO0862 (α) | NC | |

| SSO0282 (β) | NC | ||

| SSO3000 (γ) | −3.0 | 60 vs −10 | |

| Sso7d | SSO9180 | +4.0 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO9535 | +4.6 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO10610 | +4.6 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Protein and mRNA turnover | |||

| Proteasome | SSO0738 (α) | NC | |

| SSO0278 (β1) | NC | ||

| SSO0766 (β2) | NC | ||

| SSO0271 (PAN) | −7.2 | 5 vs −10 | |

| Exosome | SSO0732 rrp42 | −6.5 | 5 vs −10 |

| SSO0735 rrp41 | −4.3 | 5 vs −10 | |

| SSO0736 rrp4 | −10.6 | 5 vs −10 |

NC, no change; PAN, proteasome-associated nucleotidase; USP, universal stress protein.

IS elements, transposes, and resolvases.

The S. solfataricus genome encodes more than 200 insertion sequence (IS) elements and associated fragments, which, taken together, represent approximately 10% of the genome (5). IS elements and miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are thought to be responsible for genome shuffling in S. solfataricus and S. tokodai. In sharp contrast, S. acidocaldarius contains no IS elements (6). Since the presence of multiple (almost identical) copies of IS element-related sequences complicated gene expression analysis in some cases, the entire subset of these ORFs was treated as a group. Extensive differential expression of IS sequences, transposases, and resolvases (a group of ∼400 ORFs) was noted under HS, with ∼60% of these ORFs differentially expressed for at least one time point comparison. This proportion was more than twice that observed during unstressed growth (unpublished data), implicating HS in IS element differential expression. These ORFs typically responded early, with as many as 208 ORFs (203 up/5 down) differentially expressed within 5 min after HS, representing no less than ∼37% of all up-regulated genes for this time point comparison and indicating a crucial role for transposition and genome plasticity (24) in early HS response. The mobility of IS elements can increase genetic diversity in the face of stress (16) by either causing mutations (11, 32), moving genes to a different chromosomal location, deleting or inverting ORFs, inactivating some by insertion, or activating genes by positioning a promoter upstream of the coding region (3). Moreover, transposon mutagenesis was shown to be the cause of the high mutation rate observed in S. solfataricus (32). The fact that a selective agent, in this case HS, could directly increase genetic mutation and rearrangement rates in S. solfataricus suggests that mutations are not random and spontaneous (8).

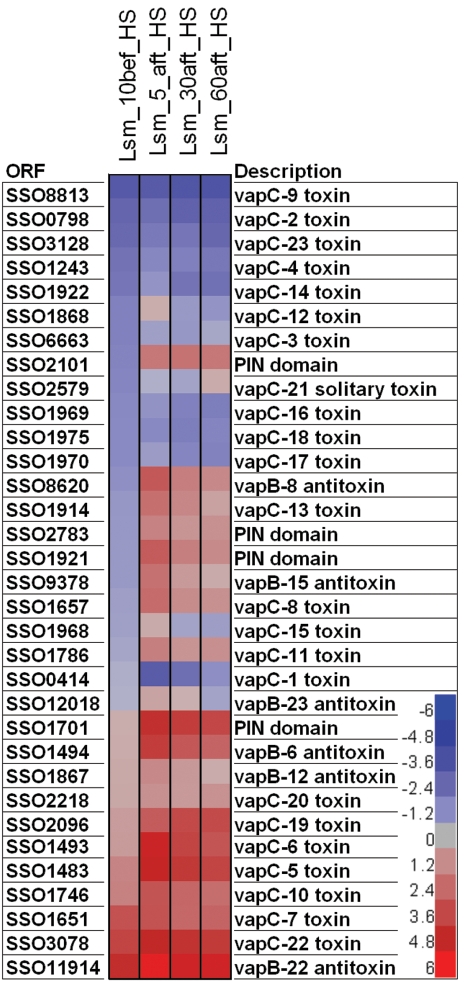

Toxin-antitoxin loci also responded to HS.

Only one toxin-antitoxin (TA) family (vapBC) has been identified in the S. solfataricus genome, represented by 22 TA pairs and 1 solitary toxin (38). Although first thought to be exclusively associated with postsegregational killing, recent studies have shown that TA loci are also involved in stress response (7) and trigger a reversible bacteriostatic effect rather than a lethal one (18). Toxins typically contain a PIN domain, which has been shown to function as an exonuclease (2). By cleaving mRNAs, toxins interfere with transcription, thereby modulating metabolic activity (2). Here, specific TA loci responded to HS, presumably to slow growth and thus minimize the burden of housekeeping functions. It has been proposed that TA loci are constitutively repressed (17), but here it was noted that, even under unstressed conditions, vapBC ORF expression levels differ, ranging from very low (vapC-9) to very high (vapBC-22) (Fig. 3). Consequently, not only was vapBC locus expression heat stress induced in S. solfataricus, but many loci were transcribed even under normal growth conditions. This suggests that (i) vapBC loci may play various roles in S. solfataricus, (ii) activation mechanisms (protease based) and toxin potency may differ from one TA pair to another, and (iii) cells may use TA systems to modulate their metabolic activity even in the absence of perturbations. Efforts are now under way to test these hypotheses.

FIG. 3.

Heat plot representing relative expression levels for toxins, antitoxins, and PIN domain-containing ORFs. Each column represents data for a given time point (from left to right, 10 min before HS and then 5, 30, and 60 min after reaching 90°C). Missing antitoxins correspond to ORFs that had not been reported in the initial genome sequence (49).Values are sorted according to the preshock time point. Data are centered on zero (gray), which represents the average gene expression level over the entire genome, where each unit above (red) or below (blue) equals one standard deviation from the average.

While thermal stress response in S. solfataricus needs to be examined further, dynamic genome-wide differential expression analysis such as that reported here can lead to new insights into the adaptive and governing mechanisms underlying extreme thermoacidophily.

Supplemental material.

Comprehensive listings and data analysis for the dynamic heat shock experiments with S. solfataricus are reported as supplemental material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by grants from the DOE Energy Biosciences, NASA Exobiology, and NSF Biotechnology programs.

We also acknowledge K. Auernick, C.-J. Chou, M. Johnson, C. Montero, and J. Stewart for their assistance with sample processing and S. Conners and R. Wolfinger for help with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aertsen, A., and C. W. Michiels. 2004. Stress and how bacteria cope with death and survival. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 30:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arcus, V. L., K. Backbro, A. Roos, E. L. Daniel, and E. N. Baker. 2004. Distant structural homology leads to the functional characterization of an archaeal PIN domain as an exonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 279:16471-16478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blount, Z. D., and D. W. Grogan. 2005. New insertion sequences of Sulfolobus: functional properties and implications for genome evolution in hyperthermophilic archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 55:312-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonyaratanakornkit, B. B., A. J. Simpson, T. A. Whitehead, C. M. Fraser, N. M. El-Sayed, and D. S. Clark. 2005. Transcriptional profiling of the hyperthermophilic methanarchaeon Methanococcus jannaschii in response to lethal heat and non-lethal cold shock. Environ Microbiol. 7:789-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugger, K., P. Redder, Q. She, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, and R. A. Garrett. 2002. Mobile elements in archaeal genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugger, K., E. Torarinsson, P. Redder, L. Chen, and R. A. Garrett. 2004. Shuffling of Sulfolobus genomes by autonomous and non-autonomous mobile elements. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buts, L., J. Lah, M. H. Dao-Thi, L. Wyns, and R. Loris. 2005. Toxin-antitoxin modules as bacterial metabolic stress managers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30:672-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairns, J., J. Overbaugh, and S. Miller. 1988. The origin of mutants. Nature 335:142-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canganella, F., J. M. Gonzalez, M. Yanagibayashi, C. Kato, and K. Horikoshi. 1997. Pressure and temperature effects on growth and viability of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus peptonophilus. Arch. Microbiol. 168:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavicchioli, R., T. Thomas, and P. M. Curmi. 2000. Cold stress response in Archaea. Extremophiles 4:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao, L., C. Vargas, B. B. Spear, and E. C. Cox. 1983. Transposable elements as mutator genes in evolution. Nature 303:633-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhabra, S. R., K. R. Shockley, S. B. Conners, K. L. Scott, R. D. Wolfinger, and R. M. Kelly. 2003. Carbohydrate-induced differential gene expression patterns in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J. Biol. Chem. 278:7540-7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chhabra, S. R., K. R. Shockley, D. E. Ward, and R. M. Kelly. 2002. Regulation of endo-acting glycosyl hydrolases in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima grown on glucan- and mannan-based polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conners, S. B., C. I. Montero, D. A. Comfort, K. R. Shockley, M. R. Johnson, S. R. Chhabra, and R. M. Kelly. 2005. An expression-driven approach to the prediction of carbohydrate transport and utilization regulons in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J. Bacteriol. 187:7267-7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dopson, M., C. Baker-Austin, P. R. Koppineedi, and P. L. Bond. 2003. Growth in sulfidic mineral environments: metal resistance mechanisms in acidophilic micro-organisms. Microbiology 149:1959-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichenbaum, Z., and Z. Livneh. 1998. UV light induces IS10 transposition in Escherichia coli. Genetics 149:1173-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerdes, K., S. K. Christensen, and A. Lobner-Olesen. 2005. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes, C. S., and R. T. Sauer. 2003. Toxin-antitoxin pairs in bacteria: killers or stress regulators? Cell 112:2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber, H., and D. Prangishvili. 21 December 2004, posting date. Sulfolobales. In M. Dworkin et al. (ed.), The prokaryotes: an evolving electronic resource for the microbiological community. [Online.] Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. http://link.springer-ny.com/link/service/books/10125/.

- 20.Johnson, M. R., C. I. Montero, S. B. Conners, K. R. Shockley, S. L. Bridger, and R. M. Kelly. 2005. Population density-dependent regulation of exopolysaccharide formation in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Mol. Microbiol. 55:664-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagawa, H. K., J. Osipiuk, N. Maltsev, R. Overbeek, E. Quaite-Randall, A. Joachimiak, and J. D. Trent. 1995. The 60 kDa heat shock proteins in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae. J. Mol. Biol. 253:712-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagawa, H. K., T. Yaoi, L. Brocchieri, R. A. McMillan, T. Alton, and J. D. Trent. 2003. The composition, structure and stability of a group II chaperonin are temperature regulated in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Mol. Microbiol. 48:143-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlin, S., J. Mrazek, J. Ma, and L. Brocchieri. 2005. Predicted highly expressed genes in archaeal genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:7303-7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kidwell, M. G., and D. Lisch. 1997. Transposable elements as sources of variation in animals and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7704-7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komori, K., T. Miyata, J. DiRuggiero, R. Holley-Shanks, I. Hayashi, I. K. Cann, K. Mayanagi, H. Shinagawa, and Y. Ishino. 2000. Both RadA and RadB are involved in homologous recombination in Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33782-33790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krulwich, T. A. 1995. Alkaliphiles: ‘basic’ molecular problems of pH tolerance and bioenergetics. Mol. Microbiol. 15:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laksanalamai, P., and F. T. Robb. 2004. Small heat shock proteins from extremophiles: a review. Extremophiles 8:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Garcia, P., and P. Forterre. 1999. Control of DNA topology during thermal stress in hyperthermophilic archaea: DNA topoisomerase levels, activities and induced thermotolerance during heat and cold shock in Sulfolobus. Mol. Microbiol. 33:766-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Garcia, P., S. Knapp, R. Ladenstein, and P. Forterre. 1998. In vitro DNA binding of the archaeal protein Sso7d induces negative supercoiling at temperatures typical for thermophilic growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:2322-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macalady, J. L., M. M. Vestling, D. Baumler, N. Boekelheide, C. W. Kaspar, and J. F. Banfield. 2004. Tetraether-linked membrane monolayers in Ferroplasma spp: a key to survival in acid. Extremophiles 8:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marteinsson, V. T., A. L. Reysenbach, J. L. Birrien, and D. Prieur. 1999. A stress protein is induced in the deep-sea barophilic hyperthermophile Thermococcus barophilus when grown under atmospheric pressure. Extremophiles 3:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martusewitsch, E., C. W. Sensen, and C. Schleper. 2000. High spontaneous mutation rate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is mediated by transposable elements. J. Bacteriol. 182:2574-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maupin-Furlow, J. A., H. L. Wilson, S. J. Kaczowka, and M. S. Ou. 2000. Proteasomes in the archaea: from structure to function. Front. Biosci. 5:D837-D865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moggs, J. G., and G. Orphanides. 2003. Genomic analysis of stress response genes. Toxicol. Lett. 140-141:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mombelli, E., E. Shehi, P. Fusi, and P. Tortora. 2002. Exploring hyperthermophilic proteins under pressure: theoretical aspects and experimental findings. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1595:392-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Napoli, A., A. Valenti, V. Salerno, M. Nadal, F. Garnier, M. Rossi, and M. Ciaramella. 2004. Reverse gyrase recruitment to DNA after UV light irradiation in Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 279:33192-33198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nies, D. H. 1999. Microbial heavy-metal resistance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:730-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandey, D. P., and K. Gerdes. 2005. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:966-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedone, E., S. Bartolucci, and G. Fiorentino. 2004. Sensing and adapting to environmental stress: the archaeal tactic. Front. Biosci. 9:2909-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peeples, T. L., and R. M. Kelly. 1995. Bioenergetic response of the thermoacidophilic archaeum Metallosphaera sedula to thermal and nutritional stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2314-2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Portnoy, V., E. Evguenieva-Hackenberg, F. Klein, P. Walter, E. Lorentzen, G. Klug, and G. Schuster. 2005. RNA polyadenylation in Archaea: not observed in Haloferax while the exosome polynucleotidylates RNA in Sulfolobus. EMBO Rep. 6:1188-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Pysz, M. A., D. E. Ward, K. R. Shockley, C. I. Montero, S. B. Conners, M. R. Johnson, and R. M. Kelly. 2004. Transcriptional analysis of dynamic heat-shock response by the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Extremophiles 8:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reich, C. I., L. K. McNeil, J. L. Brace, J. K. Brucker, and G. J. Olsen. 2001. Archaeal RecA homologues: different response to DNA-damaging agents in mesophilic and thermophilic Archaea. Extremophiles 5:265-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robb, F. T., and D. S. Clark. 1999. Adaptation of proteins from hyperthermophiles to high pressure and high temperature. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:101-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohlin, L., J. D. Trent, K. Salmon, U. Kim, R. P. Gunsalus, and J. C. Liao. 2005. Heat shock response of Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J. Bacteriol. 187:6046-6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rouillard, J.-M., M. Zuker, and E. Gulari. 2003. OligoArray 2.0: design of oligonucleotide probes for DNA microarrays using a thermodynamic approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3057-3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell, N. J. 1989. Adaptive modifications in membranes of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 21:93-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakoh, M., K. Ito, and Y. Akiyama. 2005. Proteolytic activity of HtpX, a membrane-bound and stress-controlled protease from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33305-33310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.She, Q., R. K. Singh, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, G. Allard, M. J. Awayez, C. C.-Y. Chan-Weiher, G. Clausen Ib, B. A. Curtis, A. De Moors, G. Erauso, C. Fletcher, P. M. K. Gordon, I. Heikamp-de Jong, A. C. Jeffries, C. J. Kozera, N. Medina, X. Peng, H. P. Thi-Ngoc, P. Redder, M. E. Schenk, C. Theriault, N. Tolstrup, R. L. Charlebois, W. F. Doolittle, M. Duguet, T. Gaasterland, R. A. Garrett, M. A. Ragan, C. W. Sensen, and J. Van der Oost. 2001. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shockley, K. R., D. E. Ward, S. R. Chhabra, S. B. Conners, C. I. Montero, and R. M. Kelly. 2003. Heat shock response by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2365-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun, M. M., and D. S. Clark. 2001. Pressure effects on activity and stability of hyperthermophilic enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 334:316-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trent, J. D., J. Osipiuk, and T. Pinkau. 1990. Acquired thermotolerance and heat shock in the extremely thermophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus sp. strain B12. J. Bacteriol. 172:1478-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van de Vossenberg, J. L. C. M., A. J. M. Driessen, W. Zillig, and W. N. Konings. 1998. Bioenergetics and cytoplasmic membrane stability of the extreme acidophilic thermophilic Archaeon Picrophilus oshimae. Extremophiles 2:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolfinger, R. D., G. Gibson, E. D. Wolfinger, L. Bennett, H. Hamadeh, P. Bushel, C. Afshari, and R. S. Paules. 2001. Assessing gene significance from cDNA microarray expression data via mixed models. J. Comput. Biol. 8:625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zillig, W., K. O. Stetter, A. Wunderl, W. Schultz, H. Priess, and I. Scholtz. 1980. The Sulfolobus-“Caldariella” group: taxonomy on the basis of the structure of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Arch. Mikrobiol. 125:259-269. (In German.) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.