Abstract

Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 grows on biphenyl and salicylate as sole sources of carbon. The biphenyl-catabolic (bph) genes are organized as bphR1A1A2(orf3)A3A4BCX0X1X2X3D, encoding the enzymes for conversion of biphenyl to acetyl coenzyme A. In this study, the salicylate-catabolic (sal) gene cluster encoding the enzymes for conversion of salicylate to acetyl coenzyme A were identified 6.6-kb downstream of the bph gene cluster along with a second regulatory gene, bphR2. Both the bph and sal genes were cross-regulated positively and/or negatively by the two regulatory proteins, BphR1 and BphR2, in the presence or absence of the effectors. The BphR2 binding sequence exhibits homology with the NahR binding sequences in various naphthalene-degrading bacteria. Based on previous studies and the present study we propose a new regulatory model for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in strain KF707.

The degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 has been studied previously. KF707 possesses a chromosomal bph gene cluster that is responsible for catabolism of biphenyl (9-11, 30). This gene cluster is bphR1A1A2(orf3)bphA3A4BCX0X1X2X3D. Watanabe et al. reported that regulatory protein BphR1 belonging to the GntR family activates transcription of its own gene, bphX0X1X2X3, and bphD and that another regulatory protein, BphR2 belonging to the LysR family, activates transcription of bphR1 and bphA1A2(orf3)A3A4BC (33, 34). Strain KF707 does not grow on naphthalene but grows on salicylate (33); however, the details concerning the regulatory system mediated by the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins for the catabolism of biphenyl and salicylate in strain KF707 are still unclear.

BphR2 was previously cloned as a homologue of NahR, the transcriptional regulator of naphthalene- and salicylate-catabolic operons in the NAH7 plasmid of Pseudomonas putida G7 (14, 33). In NAH7, transcription of nahR is induced by salicylate. The NahR protein activates transcription of the upper-pathway genes (nah operon) for conversion of naphthalene to salicylate. The NahR protein also stimulates transcription of the lower-pathway genes (sal operon) for conversion of salicylate to acetyl coenzyme A and pyruvate. The nahR gene is between the nah and sal operons (3, 4, 12, 26-28, 35-38). It was previously reported that the biphenyl- and salicylate-utilizing organism P. putida KF715 has a bph gene cluster that is nearly identical to that of strain KF707 and that the sal gene cluster is located ca. 10 kb downstream of the bph gene cluster on the 90-kb conjugative transposon (termed the bph-sal element) (15, 18). This information allowed us to predict that the bphR2 gene is present between the bph and sal gene clusters and that the BphR2 protein regulates transcription of the sal gene cluster together with the bph gene cluster in strain KF707.

There have been several reports on the regulation of bph genes to date. The bph gene clusters in Tn4371 of Ralstonia eutropha A5 and Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102, bphSEFGA1A2A3BCDA4R, are negatively regulated by the BphS repressor (16, 19). In addition to BphS, BphR in Tn4371, strain KKS102, and Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199 has been assigned to a possible regulator belonging to the LysR family, but the functions have remained unclear (16, 19, 23). The bpdC1C2BADEF operon in gram-positive Rhodococcus sp. strain M5 is regulated by the two-component signal transduction system comprised of the BpdS sensor histidine kinase and the BpdT response regulator (13). Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 also has a possible regulator, ORF10103, belonging to the LysR family. ORF10103 exhibits no significant amino acid sequence similarity with BphR2 and is thought to stimulate transcription of the LB400 bph genes in response to biphenyl (6).

During further investigation of the regulatory system of biphenyl and salicylate in KF707, we found that in the presence of salicylate, both bphR1 and bphR2 disruptants grew with lag times shorter than the lag times of wild-type strain KF707. Here we report that the regulatory proteins, BphR1 and BphR2, cross-regulate the bph and sal gene clusters in strain KF707.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The biphenyl-utilizing strain P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 was grown at 30°C in basal salt medium (BSM) supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) biphenyl (Kishida) as the sole source of carbon, as described previously (9). Biphenyl-utilizing defective variants of KF707, such as KF707ΔR1 (bphR1::Tcr; formerly KF7095), KF707ΔR2 (bphR2::Kmr; formerly KF707 dR20), and KF707R2+ (KF707ΔR2 carrying pTWF17 containing bphR2; formerly KF707 dRC29) were constructed previously (33, 34). These strains were grown in BSM supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium succinate. For growth on salicylate, BSM supplemented with sodium salicylate (1 mM; Nacalai Tesque) was used. For agar plates (1.5%, wt/vol), biphenyl was supplied as a vapor in the inverted lid of a petri dish. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. The concentrations of the antibiotics used were as follows: for E. coli strains, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml tetracycline, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 50 μg/ml kanamycin; and for P. pseudoalcaligenes strains, 25 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml tetracycline, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 50 μg/ml kanamycin.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. pseudoalcaligenes strains | ||

| KF707 | Bph+, wild type | 9 |

| KF707ΔR1 | Bph−, bphR1::Tcr | 33 |

| KF707ΔR2 | Bph−, bphR2::Tcr | 32 |

| KF707R2+ | KF707ΔR2 carrying pTWF17 containing bphR2; Bph+ Apr Kmr | 32 |

| E. col strains | ||

| JM109 | Host strain for DNA manipulation | Takara Shuzo |

| BL21(DE3) | Host strain for expression | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTWF3 | 0.75-kb NcoI-SalI PCR fragment in pET32b(+); bphR1 | 33 |

| pTWF17 | 1.8-kb EcoRI fragment containing bphR2 coding sequence in pMMB66EH; Apr | 32 |

| pTWF21 | 0.95-kb NcoI-KpnI fragment from KF707 in pTV118N; bphR2 | 32 |

| pGEM-T Easy | Cloning vector; Apr | Promega |

| pFHF10 | 161-bp PCR fragment in pGEM-T Easy, including bphR1 promoter | This study |

| pFHF11 | 123-bp PCR fragment in pGEM-T Easy, including bphA1 promoter | This study |

| pFHF12 | 183-bp PCR fragment in pGEM-T Easy, including salA promoter | This study |

| pFHF13 | 585-bp PCR fragment in pGEM-T Easy, including intervening region of bphR2 and salA | This study |

| pHGS396-xylE | 0.4-kb fragment containing xylE coding sequence from pWWO; Cmr | This study |

Bph+, able to grow on biphenyl as a sole carbon source; Bph−, unable to grow on biphenyl as a sole carbon source; Apr, resistance to ampicillin; Tcr, resistance to tetracycline; Kmr, resistance to kanamycin; Cmr, resistance to chloramphenicol.

DNA manipulation, cloning, sequencing, and RNA preparation.

DNA manipulation was performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (25). Plasmids were prepared by the rapid alkaline procedure. All primers used in this study are available on request. The primers used for cloning of the sal genes in strain KF707 were designed based on the information for the genes of strain KF715 (GenBank accession no. AY294313). The DNA fragments were cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the nucleotide sequences were determined by the chain termination method with a DNA sequencer (Li-Cor IR2 Global Edition). RNA was prepared from cells grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7 as described by Ausubel et al. (2). The concentration and purity of RNA were estimated from the A260/A280 ratio and from the RNA bands on a formaldehyde-denatured agarose gel electrophoresis gel.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

A 25-μl reverse transcription (RT) reaction mixture contained 2 μg of total RNA, 1 μg of forward primer, 1 μg of reverse primer, 1 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 4 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 40 U of RNase inhibitor (Toyobo), 15 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, and 1× avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase buffer (Promega). RT was carried out for 1 h with a thermal cycler (PC-700; Astec) at 53°C. A real-time PCR was performed using Light Cycler Quick System 350S according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). Transcription of the 16S rRNA gene was measured as the internal standard.

Purification of BphR1 and BphR2 proteins.

E. coli BL21(DE3)(pTWF3) and E. coli JM109(pTWF21) were grown in LB medium containing ampicillin to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. The proteins were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h. The cells were suspended in cold binding buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, and 10% glycerol and were disrupted with a French pressure cell (Ohtake). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The resultant supernatant was mixed with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN) and incubated on ice for 1 h. The matrix was washed twice with binding buffer containing 50 mM imidazole. The proteins were eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Preparation of ring meta-cleavage yellow compounds from biphenyl and salicylate.

P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707ΔR1 and E. coli JM109(pHSG396-xylE) were grown overnight in BSM supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium succinate and in LB medium, respectively. The cells were harvested and suspended in the binding buffer. 2,3-Dihydroxybiphenyl (Wako) and catechol (0.2%, wt/vol; Sigma) were added to the cell suspensions of strains KF707ΔR1 and JM109 carrying the xylE gene, respectively. After 2 h of incubation, we confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (model QP5000; Shimadzu) that all of the 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl and catechol used in this study were converted to 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dianoate (HOPD) and 2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde (HMSA), respectively. Then the cells were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant containing the ring meta-cleavage yellow compound was filter sterilized and stored at −80°C until use.

Gel shift assay.

The DNA fragments used for the gel shift assays are shown in Fig. 1A. Fragment GS1 covering the bphR1 promoter/operator region was 161 nucleotides (nt) long, fragment GS2 covering the bphABC promoter/operator was 123 nt long, and fragment GS3 covering the bphR2 promoter/operator and salA promoter/operator was 166 nt long. These DNA fragments were amplified by PCR. The DNA fragments obtained were inserted into the pGEM-T Easy vector, yielding pFHF10, pFHF11, and pFHF12, respectively. A digoxigenin (DIG) oligonucleotide 3′-end-labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics) was used for labeling the DNA fragments according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). The reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained binding buffer composed of 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 6 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Roche), and 0.8 pmol of DIG-11-ddUTP-labeled DNA and 2 μg of purified BphR1 or 100 ng of the BphR2 protein. When necessary, 100 pmol of a cold target DNA fragment, 100 pmol of unrelated DNA (5′-AAGGCTCTCGAGCCTCAAACCGAATTCCCGAAC-3′), 1 mM biphenyl, 1 mM HOPD, 1 mM sodium salicylate, 1 mM HMSA, or 1 mM sodium benzoate (Sigma) was added to the reaction mixture. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, loading buffer containing 0.25× 60% Tris acetate-EDTA buffer (40 mM Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA) and 40% glycerol was added, and the labeled DNA was separated by electrophoresis at 150 V (constant voltage) in an 8% polyacrylamide gel with cold 0.25× Tris acetate-EDTA buffer for 2 h. After electrophoresis, the DNA fragments were transferred onto Biodyne B (PALL). The DIG-labeled DNA fragments were detected by using a detection kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Roche Diagnostics).

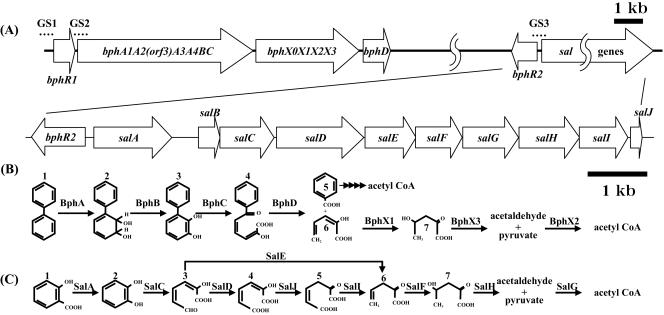

FIG. 1.

Organization of bph and sal gene clusters (A) and catabolic pathways of biphenyl (B) and salicylate (C) in P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. (A) GS1 (161 bp), GS2 (123 bp), and GS3 (166 bp) used in the gel shift assays are indicated by dotted lines. (B) Compounds involved in biphenyl catabolism are indicated as follows: 1, biphenyl; 2, 2,3-dihydroxy-4-phenylhexa-4,6-diene; 3, 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl; 4, HOPD; 5, benzoic acid; 6, 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoic acid; and 7, 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate. The enzymes and proteins involved are biphenyl dioxygenase (BphA), dihydrodiol dehydrogenase (BphB), 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase (BphC), 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoate hydrolase (BphD), 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoate hydratase (BphX1), 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate aldolase (BphX3), and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (BphX2). (C) Compounds involved in salicylate catabolism are indicated as follows: 1, salicylate; 2, catechol; 3, HMSA; 4, 2-hydroxyhexa-2,4-diene-1,6-dioate; 5, 2-oxohexa-3-ene-1,6-dioate; 6, 2-oxopent-4-enoate; and 7, 4-hydroxy-2-oxovalerate. The enzymes and proteins involved are salicylate hydroxylase (SalA), catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (SalC), hydroxymuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SalD), 4-oxalocrotonate isomerase (SalJ), 4-oxalocrotonate decarboxylase (SalI), 2-oxopent-4-enoate hydratase (SalF), 2-oxo-4-hydroxypentanoate aldolase (SalH), and hydroxymuconic semialdehyde hydrolase (SalE). acetyl CoA, acetyl coenzyme A.

Primer extension assay.

A primer extension assay was performed with a primer extension kit used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The primers used in this study were synthesized and labeled with IRD-800 (Aloka). A 10-μg aliquot of total RNA was used in the primer extension reaction. The end-labeled primers were complementary to 21- or 28-nt sequences located 6 and 14 nucleotides downstream of the bphR2 and salA start codons, respectively. The extension signals were detected with a DNA sequencer (Li-Cor).

DNase I footprinting analysis.

A 585-bp DNA fragment that included the region between bphR2 and salA was amplified by PCR and inserted into the pGEM-T Easy vector, yielding pFHF13. An IRD-700-labeled DNA fragment was prepared by PCR with pFHF13. In this analysis, IRD-700-labeled M13 primers were used (Aloka). Footprinting was performed at room temperature for 30 min with a 100-μl reaction mixture containing RW buffer (5 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 10 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% glycerol), 1 mM MgCl2, an IRD-700-labeled DNA fragment at a concentration of 10 nM, and 1 μg BphR2 protein; 0.75 U of DNase I (Amersham) was added to the reaction mixture, which was incubated at room temperature for 1 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 100 μl of a stop solution containing 4 M NaCl and 100 mM EDTA. Digested DNA fragments were analyzed with a DNA sequencer (Li-Cor).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of salABCDEFGHIJ has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. DQ100350.

RESULTS

Cloning of the sal gene cluster and location of bphR2.

We previously reported that P. putida KF715, another biphenyl-utilizing strain, possesses a conjugative bph-sal element and that the nahR-like gene is located far downstream of bphD and upstream of the sal gene cluster (18). Based on this information, we attempted to identify the bphR2 and sal gene cluster in the chromosomal DNA of strain KF707 and the region between bphR2 and salA, as well as the sal gene cluster (Fig. 1A).

The bphR2 gene was found to be located 153 bp upstream from the start codon of salA in strain KF707. The region between bphR2 and salA in strain KF707 exhibited 100% identity with the region between bphR2 and salA in strain KF715, 63.3% identity with the region between nahR and nahG in P. putida NCIB 9816-4 (21), and 92.9% identity with the region between nahR and nahG in P. stutzeri AN10 (Fig. 2C) (3, 4).

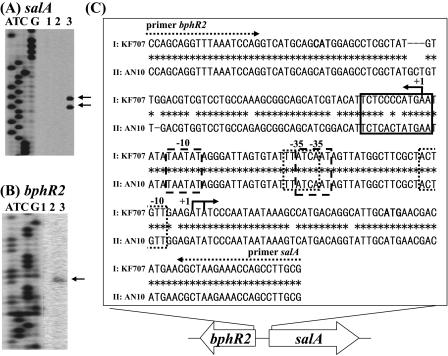

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional initiation sites of salA (A) and bphR2 (B) and possible functional regions (C). (A and B) The end-labeled primers were complementary to regions located 14 bp or 6 bp downstream of the salA and bphR2 start codons, respectively. Lanes A, T, C, and G show the results of the dideoxy sequencing reaction carried out with the M13 forward primer. Lane 1, primer extension reaction with RNA prepared from KF707 cells grown with succinate; lane 2, primer extension reaction for cells grown with biphenyl plus succinate; lane 3, primer extension reaction for cells grown with salicylate plus succinate. The arrows indicate the transcriptional initiation sites. (C) Sequences I and II indicate the regions between the bphR2 and salA genes in KF707 and between the nahR and nahG genes in P. stutzeri AN10 (GenBank accession no. AF039534), respectively. Possible −10 and −35 promoter regions for bphR2 and sal genes are indicated by dotted boxes. The possible binding stretch (T-N11-A) of NahR is indicated by a box. The dotted arrows indicate the primers. The solid arrows indicate transcriptional initiation sites of bphR2 and salA. The start codons of bphR2 and salA are indicated by boldface type.

When PCR was performed to amplify the region between bphD and bphR2, we obtained an ca. 6.6-kb DNA fragment, indicating that bphR2 is located 6.6 kb downstream of bphD (Fig. 1A). In addition, we cloned the sal genes, designated salA, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F, -G, -H, -I, and -J. The DNA sequence of these genes exhibited 95.1% identity with the sequence of strain KF715 (GenBank accession no. AY294313) and 94.2% identity with the sequence of strain AN10 (GenBank accession no. AF039534).

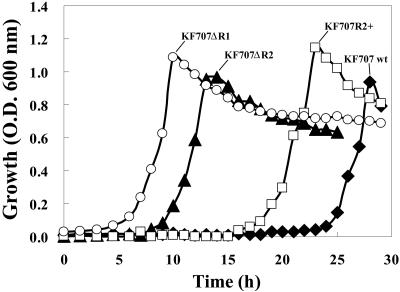

Growth of KF707ΔR1 and KF707ΔR2 on salicylate.

In order to examine the role of bphR1 and bphR2 in salicylate metabolism, we examined the growth of wild-type strain KF707, KF707ΔR1 harboring a disruption of bphR1, KF707ΔR2 harboring a disruption of bphR2, and KF707R2+, which carries plasmid-borne copies of bphR2. We compared the growth of these strains with salicylate, succinate, or benzoate as the sole source of carbon. No significant differences in growth with succinate or benzoate were observed for these four strains (data not shown). In the presence of salicylate, however, strains KF707ΔR1 and KF707ΔR2 grew with lag phases that were shorter (3 h and 8 h, respectively) than the lag phases observed for wild-type strain KF707 (23 h) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, KF707R2+ grew with a lag phase that was intermediate between that of wild-type KF707 and that of KF707ΔR2. These results suggest that disruption of bphR1 and bphR2 significantly affects the catabolism of salicylate in strain KF707. The extended lag phase of strain KF707ΔR2 compared with that of strain KF707ΔR1 suggests that the functions of BphR1 and BphR2 are not the same.

FIG. 3.

Growth characteristics of wild-type strain KF707, KF707ΔR1, KF707ΔR2, and KF707R2+ with salicylate. Cells of strains KF707 (wild type) (⧫), KF707ΔR1 (bphR1 disruptant) (○), KF707ΔR2 (bphR2 disruptant) (▴), and KF707R2+ (KF707ΔR2 carrying pTWF17 containing bphR2) (▪) were cultured on BSM supplemented with 5 mM salicylate as the sole source of carbon. O.D.600 nm, optical density at 600 nm; wt, wild type.

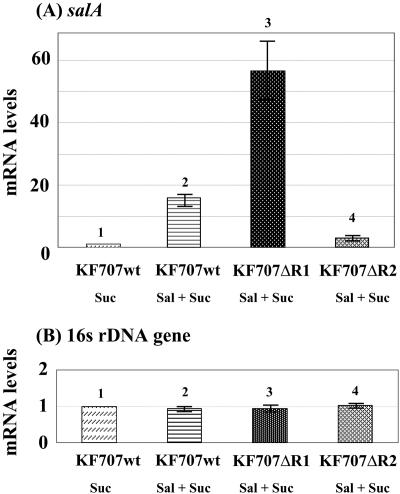

Quantitative analysis of sal gene expression.

In order to investigate how BphR1 and/or BphR2 mutations affect transcription of the sal genes, we performed a quantitative RT-PCR. In the presence of salicylate, the transcription of salA was induced in wild-type strain KF707 (Fig. 4A, bars 1 and 2). In strain KF707ΔR1, the transcription of salA was 3.6-fold higher than the transcription of salA in wild-type strain KF707 (Fig. 4A, bars 2 and 3). Conversely, in KF707ΔR2, the transcription of salA was 5.0-fold lower than the transcription of salA in wild-type strain KF707 (Fig. 4A, bars 2 and 4). These results indicate that the transcription of sal genes was negatively regulated by BphR1 and positively regulated by BphR2. In the presence of biphenyl, on the other hand, the salA gene in wild-type strain KF707 was transcribed at very low levels (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR of salA mRNA. (A) mRNA levels for the salA gene normalized to the level for succinate-grown wild-type strain KF707 cells (bar 1). (B) Transcriptional RNA levels for the 16S rRNA gene measured as an internal standard. The error bars indicate the standard deviations calculated from triplicate assays. Suc, succinate; Sal, salicylate; wt, wild type.

Transcriptional analysis of bphR2 and salA genes.

If the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins regulate the transcription of the bphR2 and/or sal genes, these proteins may bind to their promoter/operator regions. First, we performed primer extension analyses to determine the transcriptional initiation sites and possible promoter regions of the salA and bphR2 genes (Fig. 2A and B); RNAs were prepared from wild-type strain KF707 cells grown with succinate (lane 1), with succinate plus biphenyl (lane 2), and with succinate plus salicylate (lane 3). When a primer complementary to the sequence 14 bp downstream of the salA start codon was used, two extended signals were detected, but only for cells grown with salicylate (Fig. 2A, lane 3). These two A start sites were 31 nt and 33 nt upstream of the salA start codon. When a primer complementary to the sequence 6 bp downstream of the bphR2 start codon was used, an A start site located 67 nt upstream of the bphR2 start codon was detected for cultures grown in the presence of biphenyl and salicylate (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3). This result indicates that both biphenyl and salicylate stimulate bphR2 transcription. The possible promoter regions of salA and bphR2 were determined, as shown in Fig. 2C. These regions exhibited homology with the regulatory regions of naphthalene-degrading strain AN10 (21) and biphenyl-degrading strain KF715. This intervening region also contains a LysR family putative binding sequence, T-N11-A (27).

Binding of BphR1 and BphR2.

We previously reported that the BphR1 protein belonging to the GntR family binds to its own promoter/operator region and activates transcription of its own gene (34). The binding of BphR1 to this region was enhanced in the presence of HOPD (the ring meta-cleavage compound of biphenyl) (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, it was previously suggested that the BphR2 protein is involved in the transcription of bphR1 and bphA1A2(orf3)A3A4BC (33). Here we performed additional gel shift assays using purified BphR1 and BphR2. The DNA fragments used were the 3′-end-labeled 5′ flanking regions of bphR1 (GS1, bphR1 promoter/operator), bphA1 (GS2, bphA1 promoter/operator), and salA (GS3, bphR2 promoter/operator and salA promoter/operator) (Fig. 1A), all of which included the transcriptional start sites and their possible promoter/operator regions. When the BphR2 protein was added to labeled GS1 and GS2, the mobilities of the DNA fragments that included both the bphR1 promoter/operator and the bphA1 promoter/operator were significantly retarded (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 2; Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2). Addition of excess amounts of cold target DNA resulted in disappearance of the retarded DNA (Fig. 5A, lane 3; Fig 5B, lane 3). Addition of an unrelated DNA did not affect the binding of BphR2 (Fig. 5A, lane 4; Fig. 5B, lane 4). These results indicate that the binding of BphR2 protein is specific for the promoter/operator regions of both the bphR1 and bphA1 genes and that this binding results in activation of transcription.

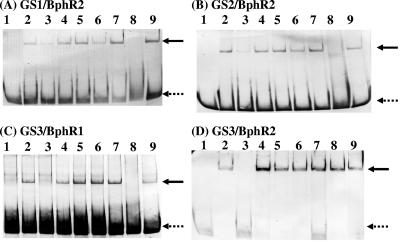

FIG. 5.

Gel shift assays of the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins.The 3′-end-labeled GS1 (A), GS2 (B), and GS3 (C and D) DNA fragments containing the possible operator regions of bphR1, bphA1, and bphR2-salA were incubated without protein (lane 1) or with purified BphR1 or BphR2 protein (lanes 2 to 9). The amount of the BphR2 protein (A, B, and D) used was 100 ng (lanes 2 to 9). The amount of the BphR1 protein (C) used was 2 μg (lanes 2 to 9). Excess unlabeled DNA (lane 3) or unrelated DNA (lane 4) was added. Biphenyl (lane 5), HOPD (lane 6), salicylate (lane 7), HMSA (lane 8), or benzoate (lane 9) was added at a concentration of 1 mM. The dotted arrows indicate free DNA bands, and the solid arrows indicate retarded DNA bands.

Interestingly, the presence of HMSA (the ring meta-cleavage compound of catechol) led to the disappearance of the shifted bands (Fig. 5A, lane 8; Fig. 5B, lane 8). This result indicates that the BphR2 protein failed to bind to the promoter/operator regions of bphR1 and bphA1 in the presence of HMSA. Thus, bphR1 and bphABC were not transcribed in this case. On the other hand, when the BphR1 protein was added to the 5′ flanking region of bphA1 (GS2), no shifted band was detected (data not shown), indicating that the transcription of bphA1A2(orf3)A3A4BC is regulated only by BphR2.

We found that the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins are significantly involved in the growth of wild-type strain KF707 with salicylate (Fig. 3) and hence in transcription of the sal genes (Fig. 4). The bphR2 gene is located 153 bp upstream of the salA start codon and is transcribed divergently from the sal genes. Therefore, it is likely that the promoter/operator regions of both the sal genes and bphR2 are in the intervening region. In general, proteins belonging to the LysR family bind to their own operators and repress transcription of their own genes in the absence of their effectors (autorepression) (27, 32). Thus, the BphR2 protein may bind to its own operator to repress its own transcription. Therefore, we performed a gel shift assay using the GS3 intergenic DNA (166 bp) containing both the transcriptional start sites and putative bphR2 promoter/operator and salA promoter/operator regions (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2C). When the BphR1 protein was added to the labeled GS3 DNA, its mobility was retarded (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 and 2). This binding was specific (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 and 4). When HMSA was added to the mixture, the shifted band was eliminated (Fig. 5C, lane 8). This result indicates that in the presence of HMSA, the BphR1 protein is released from the operator of the sal genes to relieve repression.

On the other hand, when the BphR2 protein was added to the same DNA fragment, its mobility was retarded (Fig. 5D, lanes 1 and 2), and this binding was also specific (Fig. 5D, lanes 3 and 4). Interestingly, in the presence of HMSA, the shifted band was not eliminated (Fig. 5D, lane 8). This result indicates that in the absence of HMSA the BphR2 protein binds to its own operator, while in the presence of HMSA the BphR2 protein binds to the salA operator.

DNase I footprinting analysis.

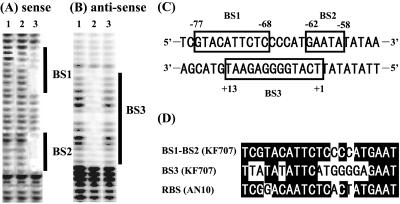

To obtain further information about the binding site of the BphR2 protein, we performed a DNase I footprinting analysis (Fig. 6). A 585-bp DNA fragment containing the salA promoter/operator region (Fig. 6A) (5′-end-labeled sense strand) and a fragment containing the bphR2 promoter/operator region (Fig. 6B) (5′-end-labeled antisense strand) were used. When the sense strand was incubated with 1 μg of BphR2 protein (lane 2), no DNA protection was observed in the absence of HMSA. On the other hand, in the presence of HMSA (lane 3), two regions ranging from nucleotide −77 to nucleotide −68 (BS1 in Fig. 6A and C) and from nucleotide −62 to nucleotide −58 (BS2 in Fig. 6A and C) were protected. When the antisense strand was incubated with the BphR2 protein (Fig. 6B), the DNA region ranging from nucleotide 1 to nucleotide 13 (BS3 in Fig. 6B and C) was protected in the absence of HMSA (Fig. 6B, lane 2). However, in the presence of HMSA, no protection was observed (lane 3). The BS1 and BS2 regions and the BS3 region overlap (Fig. 6C) and exhibit homology with the NahR binding sequences of naphthalene-degrading bacteria, especially that of strain AN10 (Fig. 6D) (22). These results indicate that in the absence of HMSA, BphR2 binds to the bphR2 operator region (BS3) to autorepress its own transcription. On the other hand, in the presence of HMSA, BphR2 binds to the salA operator region (BS1 and BS2) to activate transcription of the sal gene cluster.

FIG. 6.

(A and B) DNase I footprinting of BphR2 binding site in sense (A) and antisense (B) strands. Lane 1, DNase I-digested DNA fragment without BphR2 protein; lane 2, DNase I-digested DNA fragment with 1 μg of BphR2; lane 3, DNase I-digested DNA fragment with 1 μg of BphR2 plus 1 mM HMSA. The 5′-end-labeled sense strand includes the salA promoter/operator and its coding sequence, and the 5′-end-labeled antisense strand includes the bphR2 promoter/operator and its coding sequence. The regions protected from DNase I digestion are indicated by BS1, BS2, and BS3, respectively. (C) BphR2 binding stretches of BS1, BS2, and BS3 are enclosed in boxes. The numbers indicate the distances from the transcriptional start site. (D) Multiple alignment of BphR2 and NahR binding sequences. Conserved bases are indicated by a black background. RBS (AN10) is the regulator binding site of nahG in P. stutzeri AN10.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report for the first time that the transcription of biphenyl-catabolic gene clusters and the transcription of salicylate-catabolic gene clusters are cross-regulated by two regulatory proteins, BphR1 and BphR2, in P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. Previously, it was reported that the BphR1 protein, a GntR-type regulatory protein, acts as an activator of its own genes, bphX0X1X2X3 and bphD, and that the BphR2 protein, a LysR-type regulatory protein, activates transcription binding of bphR1 and bphA1A2(orf3)A3A4BC (33, 34). Here we found that salicylate-grown bphR1-disrupted strain KF707ΔR1 and bphR2-disrupted strain KF707ΔR2 grew with a short lag phase compared to the growth of wild-type strain KF707 (Fig. 3). This finding initially allowed us to predict that the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins may act as repressors of the sal gene cluster. In fact, this is the case for BphR1. The quantitative RT-PCR analyses and gel shift assays provided evidence that the BphR1 protein binds to the operator to repress the sal genes. Conversely, BphR2 was found to activate transcription of the sal genes in the presence of HMSA (Fig. 5). Thus, it is likely that KF707ΔR1 grew with a shorter lag phase simply because of the absence of the BphR1 repressor. For KF707ΔR2, the absence of BphR2 presumably led to low levels of the repressor BphR1 protein and a concomitantly shorter lag phase since BphR2 is involved in expression of the BphR1 protein. The intermediate lag time of KF707R2+ probably simply reflected incomplete or unbalanced complementation.

We found that the 153-bp region between the bphR2 and sal genes, as expected, contains the operator regions for divergent transcription originating from this region and a putative BphR2 binding site (T-N11-A) similar to those of other LysR family proteins (Fig. 6) (7, 27, 32). Furthermore, we detected overlapping but different binding of BphR2 within this region in the presence and absence of HMSA (Fig. 6). Generally, in the absence of an effector, binding of LysR family proteins causes repressive DNA bending (17, 32), while effectors decrease the extent of DNA bending, causing additional interactions near the −35 sequence and activation of transcription (1, 5, 7, 17, 20, 21, 27). We propose that the BphR2 protein acts in an analogous manner to autorepress transcription of bphR2 in the absence of HMSA and to stimulate transcription of sal genes in the presence of HMSA. While BphR1 binding to this region could also be detected by gel shift assays, we were unable to detect BphR1 binding by DNase I footprinting analysis, presumably because of lower DNA binding affinity.

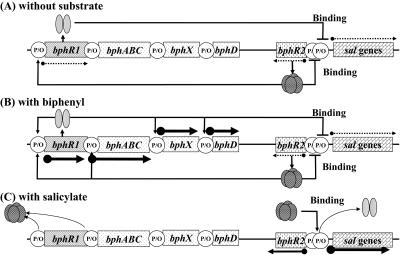

Based on the findings reported here, we propose a new model for transcriptional control of the bph and sal gene clusters of P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 (Fig. 7). In the absence of both biphenyl and salicylate (Fig. 7A), small amounts of the BphR2 protein bind to the BphR2 operator to repress bphR2 transcription (autorepression) (Fig. 5D, lane 2; Fig. 6B, lane 2). Simultaneously, small amounts of the BphR1 protein bind to the operators of the sal genes to repress the same genes (Fig. 5C, lane 2). Under these conditions, the levels of transcription of all bph and sal genes are very low (33). In the presence of biphenyl (Fig. 7B), the BphR2 protein binds to the operators of bphR1 and bphA1A2(orf3)A3A4BC and activates their transcription (Fig. 5A and B, lanes 5 to 6); thus, high levels of HOPD (the ring meta-cleavage compound) are produced from biphenyl. In the presence of HOPD, transcription of bphR1 is further promoted, and its product, BphR1, activates transcription of its own genes, bphX0X1X2X3 and bphD (34). On the other hand, the BphR1 protein also binds to the operator of the sal genes to repress its transcription (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 to 6). In the presence of salicylate (Fig. 7C), the BphR1 protein continues to repress the sal genes (Fig. 5C, lane 7). However, when low levels of Sal enzymes are expressed, HMSA is produced from salicylate. Under these conditions, the BphR1 bound to the sal operator is released (Fig. 5C, lane 8). Thus, the repression by the BphR1 protein is cancelled. Simultaneously, the binding of the BphR2 protein to the bphR2 operator is also released in the presence of HMSA (Fig. 6B, lane 3), allowing transcription of bphR2. High levels of the BphR2 protein associated with HMSA then bind to the sal operator, allowing transcription activation of the sal genes (Fig. 5D, lane 8; Fig. 6A, lane 3).

FIG. 7.

Proposed transcriptional regulatory system of the bph and sal gene clusters in P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707. Possible regulation is shown in the absence of a substrate (A), in the presence of biphenyl (B), and in the presence of salicylate (C). See text for details. The dotted arrows indicate low levels of transcription, the small solid arrows indicate moderate levels of transcription, and the large solid arrows indicate high levels of transcription. P/O, promoter/operator.

Regulation by a repressor protein is rare for catabolic pathways, except for the proteins belonging to the GntR family (32). GntR family members that control the degradation of aromatic compounds often act as transcriptional repressors in the absence of the pathway substrates. Repression is released by interaction of the regulatory protein with a substrate or its metabolite (8, 16, 32). The bphS gene products in Ralstonia eutropha A5 and Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 repress the transcription of bphEFG (corresponding to bphX1X2X3 in strain KF707) in the absence of its effector (HOPD) (16, 19). The repression mechanism of GntR-type regulators is considered to be simple hindrance of RNA polymerase binding or open-complex formation (5). It should be noted that in strain KF707, the BphR1 protein acts as an activator for biphenyl catabolism (34) and that the same protein acts as a repressor for transcription of the sal genes (Fig. 3 and 4).

As mentioned above, the BphR1 and BphR2 proteins act as bifunctional regulatory proteins in the expression of the bph and sal gene clusters in strain KF707. These bifunctional regulatory systems seem to be unique among the biphenyl- and salicylate-utilizing bacteria. Another biphenyl- and salicylate-utilizing strain, P. putida KF715, possesses the conjugative 90-kb bph-sal element carrying the bph and sal gene clusters. This element can be transferred to other P. putida strains with a high frequency (15, 18). It is thought that the transcriptional regulatory systems encoded by the conjugative elements might be regulated in a host-dependent manner. We could not transfer the bph-sal gene clusters of strain KF707 to other strains, but it is likely that these catabolic genes originated from other strains.

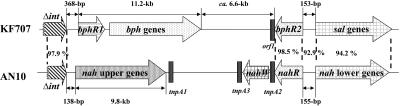

It is interesting to compare the KF707 bph and sal genes and the AN10 nah upper- and lower-pathway genes. As shown in Fig. 8, the gene organizations are very similar, except that the nah upper-pathway genes are located where the bph genes are located in KF707. The overall level of homology between the KF707 sal genes and the nah lower-pathway genes is 94.2%. The level of homology between bphR2 and nahR is 98.0%. The sequence between bphR2 and the sal genes in strain KF707 and the sequence between the nahR and nah lower-pathway genes in strain AN10 are 153 bp and 155 bp long, respectively, and exhibit 92.9% identity. Moreover, a truncated integrase gene (Δint; 3′-terminal 530 bp) located just upstream of bphR1 in strain KF707 exhibits 97.9% homology with the same region in strain AN10, which is located just upstream of the nah upper-pathway genes (3, 4). In strain KF707, the G+C contents of the bph genes (61.1%) and the sal genes (59.9%) are similar, while in strain AN10 the G+C contents of the nah upper-pathway genes (52.9%) and of the nah lower-pathway genes (60.8%) differ. Taking into account the fact that the bph-sal element acts as a conjugative transposon, as previously shown in P. putida KF715 (18), the same element may have been transferred into strain AN10. If this is the case, the bph genes in strain AN10 may have been replaced by the nah upper-pathway genes. There are two interesting regulatory differences. First, NahR acts only as a positive regulator, stimulating transcription from both the upper- and lower-pathway nah genes in strain AN10, while BphR1 and BphR2 cross-regulate both the bph and sal genes positively and/or negatively in strain KF707. Second, although both BphR2 and NahR act as activators in the presence of effectors, BphR2 responds to HMSA in strain KF707, while NahR responds to salicylate in strain AN10.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of the organization of the bph and sal genes in P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707 and the organization of the nah genes in P. stutzeri AN10. The nah sequence data for strain AN10 were obtained from GenBank accession no. AF039533 and AF039534, and the bph and sal sequence data for strain KF707 were obtained from GenBank accession no. M83673 and DQ100350. Δint, truncated integrase gene; tnpA1, tnpA2, and tnpA3, putative transposase genes; nahW, salicylate hydroxylase gene. The homology of Δint was determined for the 3′-terminal 530-bp region.

Another concern is how and why the cross-regulation of the biphenyl- and salicylate-catabolic pathways might benefit strain KF707. Direct evidence to answer this question has not been obtained yet, but the catabolism of benzoate formed from biphenyl might be involved in this cross-regulation. Benzoate is catabolized via an ortho pathway in strain KF707 (data not shown), producing cis,cis-muconate, which is known to be an inducer of the ortho pathway in pseudomonads (24). On the other hand, salicylate is catabolized via a meta pathway, producing HMSA, which is the positive effector for sal gene expression in strain KF707. Repression of the sal gene cluster by BphR1 may lead the lower pathway for benzoic acid derived from biphenyl to the ortho pathway, although the regulation of benzoate in this organism still must be elucidated. Because various pseudomonad strains harbor the bph-sal element (unpublished data), it should be interesting to investigate how the bph and sal genes, along with benzoate-catabolic genes, are regulated in a host-dependent manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Bacteriology for kind scientific and editing advice.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid (Hazardous Chemicals) from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (grant HC-04-2321-1), by a grant-in-aid (Mechanism of Biodegrading and Processing) from New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), and by research fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for young scientists.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akakura, R., and S. C. Winans. 2002. Constitutive mutations of the OccR regulatory protein affect DNA bending in response to metabolites released from plant tumors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5866-5874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. D. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 3.Bosch, R., E. Garcia-Valdes, and E. R. Moore. 1999. Genetic characterization and evolutionary implications of a chromosomally encoded naphthalene-degradation upper pathway from Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. Gene 236:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch, R., E. Garcia-Valdes, and E. R. Moore. 2000. Complete nucleotide sequence and evolutionary significance of a chromosomally encoded naphthalene-degradation lower pathway from Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. Gene 245:65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cebolla, A., C. Sousa, and V. Lorenzo. 1997. Effector specificity mutants of the transcriptional activator NahR of naphthalene degrading Pseudomonas define protein sites involved in binding of aromatic inducers. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3986-3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denef, V. J., J. Park, T. V. Tsoi, J. M. Rouillard, H. Zhang, J. A. Wibbenmeyer, W. Verstraete, E. Gulari, S. A. Hashsham, and J. M. Tiedje. 2004. Biphenyl and benzoate metabolism in a genomic context: outlining genome-wide metabolic networks in Burkholderia xenovorans LB400. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4961-4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz, E., and M. A. Prieto. 2000. Bacterial promoters triggering biodegradation of aromatic pollutants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:467-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrandez, A., B. Minambres, B. Garcia, E. R. Olicera, J. M. Luengo, J. L. Garcia, and E. Diaz. 1998. Catabolism of phenylacetic acid in Escherichia coli. Characterization of a new aerobic hybrid pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 273:25974-25986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa, K., and T. Miyazaki. 1986. Cloning of a gene cluster encoding biphenyl and chlorobiphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 166:392-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furukawa, K., H. Suenaga, and M. Goto. 2004. Biphenyl dioxygenases: functional versatilities and directed evolution. J. Bacteriol. 186:5189-5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayase, N., K. Taira, and K. Furukawa. 1990. Pseudomonas putida KF715 bphABCD operon encoding biphenyl and polychlorinated biphenyl degradation: cloning, analysis, and expression in soil bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:1160-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, J. Z., and M. A. Schell. 1991. In vivo interactions of the NahR transcriptional activator with its target sequences. Inducer-mediated changes resulting in transcription activation. J. Biol. Chem. 266:10830-10838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labbe, D., J. Garnon, and P. C. Lau. 1997. Characterization of the genes encoding a receptor-like histidine kinase and a cognate response regulator from a biphenyl/polychlorinatedbiphenyl-degrading bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. strain M5. J. Bacteriol. 179:2772-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau, P. C. K., K. Wang, D. Labbe, H. Bergeron, and J. Garnon. 1996. Two-component signal transduction systems regulating toluene and biphenyl-polychlorinated-biphenyl degradations in a soil pseudomonad and an actinomycete, p. 176-187. In T. Nakazawa, K. Furukawa, D. Hass, and S. Silver (ed.), Molecular biology of pseudomonads. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Lee, J., J. Oh, K. R. Min, and Y. Kim. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of salicylate hydroxylase gene and its 5′-flanking region of Pseudomonas putida KF715. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 218:544-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouz, S., C. Merlin, D. Springael, and A. Toussaint. 1999. A GntR-like negative regulator of the biphenyl degradation genes of the transposon Tn4371. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:790-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muraoka, S., R. Okumura, N. Ogawa, T. Nonaka, K. Miyashita, and T. Senda. 2003. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J. Mol. Biol. 328:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishi, A., K. Tominaga, and K. Furukawa. 2000. A 90-kilobase conjugative chromosomal element coding for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KF715. J. Bacteriol. 182:1949-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtsubo, Y., M. Delawary, K. Kimbara, M. Takagi, A. Ohta, and Y. Nagata. 2001. BphS, a key transcriptional regulator of bph genes involved in PCB/biphenyl degradation in Pseudomonas sp. KKS102. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36146-36154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park, H. H., H. Y. Lee, W. K. Lim, and H. J. Shin. 2005. NahR: effects of replacements at Asn 269 and Arg 248 on promoter binding and inducer recognition. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 434:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, W., C. O. Jeon, and E. L. Madsen. 2002. Interaction of NahR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, with the α subunit of RNA polymerase in the naphthalene degrading bacterium, Pseudomonas putida NCIB 9816-4. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 213:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park, W., P. S. Padmanabhan, G. J. Zylstra, and E. L. Madsen. 2002. nahR, encoding a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, is highly conserved among naphthalene-degrading bacteria isolated from a coal tar waste-contaminated site and in extracted community DNA. Microbiology 148:2319-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romine, M. F., L. C. Stillwell, K., K. Wong, S. J. Thurston, E. C. Sisk, C. Sensen, T. Gaasterland, J. K. Fredrickson, and J. D. Saffer. 1999. Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J. Bacteriol. 181:1585-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothmel, R. K., T. L. Aldrich, J. E. Houghton, W. M. Coco, L. N. Ornston, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1990. Nucleotide sequencing and characterization of Pseudomonas putida catR: a positive regulator of the catBC operon is a member of the LysR family. J. Bacteriol. 172:922-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Schell, M. A. 1985. Transcriptional control of the nah and sal hydrocarbon-degradation operons by nahR gene product. Gene 36:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schell, M. A. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schell, M. A., and E. F. Poser. 1989. Demonstration, characterization, and mutational analysis of NahR protein binding to nah and sal operon. J. Bacteriol. 166:837-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reference deleted.

- 30.Taira, K., J. Hirose, S. Hayasida, and K. Furukawa. 1992. Analysis of bph operon from the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading strain of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4844-4853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reference deleted.

- 32.Tropel, D., and J. R. van der Meer. 2004. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:474-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe, T., H. Fujihara, and K. Furukawa. 2003. Characterization of a LysR-like regulator in the biphenyl-catabolic gene cluster in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 185:3575-3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe, T., R. Inoue, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Versatile transcription of biphenyl catabolic bph operon in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31016-31023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yen, K. M., and I. C. Gunsalus. 1985. Regulation of naphthalene catabolic genes of plasmid NAH7. J. Bacteriol. 162:1008-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yen, K. M., and I. C. Gunsalus. 1982. Plasmid gene organization: naphthalene/salicylate oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:874-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.You, I. S., D. Ghosal, and I. C. Gunsalus. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of plasmid NAH7 gene nahR and DNA binding of the nahR product. J. Bacteriol. 170:5409-5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, N. Y., J., A. L. Dulayymi, M. S. Baird, and P. A. Williams. 2002. Salicylate 5-hydroxylase from Ralstonia sp. strain U2: a monooxygenase with close relationships to and shared electron transport proteins with naphthalene dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 184:1547-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]