Abstract

The auxilin family of J-domain proteins load Hsp70 onto clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) to drive uncoating. In vitro, auxilin function requires its ability to bind clathrin and stimulate Hsp70 ATPase activity via its J-domain. To test these requirements in vivo, we performed a mutational analysis of Swa2p, the yeast auxilin ortholog. Swa2p is a modular protein with three N-terminal clathrin-binding (CB) motifs, a ubiquitin association (UBA) domain, a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain, and a C-terminal J-domain. In vitro, clathrin binding is mediated by multiple weak interactions, but a Swa2p truncation lacking two CB motifs and the UBA domain retains nearly full function in vivo. Deletion of all CB motifs strongly abrogates clathrin disassembly but does not eliminate Swa2p function in vivo. Surprisingly, mutation of the invariant HPD motif within the J-domain to AAA only partially affects Swa2p function. Similarly, a TPR point mutation (G388R) causes a modest phenotype. However, Swa2p function is abolished when these TPR and J mutations are combined. The TPR and J-domains are not functionally redundant because deletion of either domain renders Swa2p nonfunctional. These data suggest that the TPR and J-domains collaborate in a bipartite interaction with Hsp70 to regulate its activity in clathrin disassembly.

INTRODUCTION

Since Palade and colleagues discovered that newly synthesized secretory proteins travel through a series of membrane-bound cellular compartments to reach the extracellular space (Palade, 1975), a growing body of evidence indicates that vesicle-mediated transport plays a major role in moving proteins as well as lipids through the secretory and endocytic pathways (Bonifacino and Glick, 2004). Vesicle formation and cargo sorting are facilitated by different coat proteins at specific donor sites. Clathrin was the first coat protein discovered (Roth and Porter, 1964; Pearse, 1975, 1976) and is involved in forming clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) from the plasma membrane (PM) for receptor-mediated endocytosis, and the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and endosomes for post-Golgi sorting events (Kirchhausen, 2000; Brodsky et al., 2001; Traub, 2005). Clathrin undergoes a highly dynamic assembly and disassembly cycle coupled with the corresponding vesicle budding and uncoating cycle. The assembly process is believed to drive vesicle budding and is facilitated by donor-membrane specific adaptor proteins (APs) that bind cargo for inclusion into CCVs (Robinson, 2004). Elegant biochemical studies have implicated heat shock protein 70 or heat shock cognate 70 (Hsp70/Hsc70) and its cochaperone auxilin in clathrin disassembly, which is needed for vesicle fusion with an acceptor membrane as well as recycling of free triskelia (Chappell et al., 1986; Rothman and Schmid, 1986; Ungewickell et al., 1995, 1997; Barouch et al., 1997; Greener et al., 2000; Fotin et al., 2004; Gruschus et al., 2004).

Auxilin family members contain a J-domain, a signature for the Hsp40 cochaperone superfamily, that can stimulate the ATPase activity of their partner Hsp70s, thus regulating the interaction between Hsp70 and its client proteins (Ungewickell et al., 1995; Greener et al., 2000; Umeda et al., 2000). The J-domain is thought to be the major binding site and minimal region needed for interaction between Hsp40 members and Hsp70 (Walsh et al., 2004). The structures of several J-domains have been solved, showing a 4-helical bundle with a nearly invariant histidine, proline, and aspartic acid (HPD motif) located between helix 2 and helix 3 (Hennessy et al., 2005). Mutation of the HPD motif typically abolishes Hsp70 stimulation and compromises the physical interaction between Hsp40 and Hsp70 (Mayer et al., 1999; Wittung-Stafshede et al., 2003). However, the significance of this HPD motif in J-domain function has not been tested as extensively in vivo as it has in vitro. Hsp40 members usually have other domains, besides the J-domain, that can interact with client proteins. This adaptor feature enables Hsp40s to harness Hsp70 chaperone function appropriately at specific sites for specific tasks (Walsh et al., 2004). For example, auxilin has a clathrin-binding (CB) region, allowing it to recruit Hsp70 onto clathrin baskets for disassembly. Several short peptide sequences within the unstructured clathrin-binding domain of auxilin, such as DPF, WDW, NWQ, and DLL, are key determinants for interaction with clathrin in vitro (Scheele et al., 2003), although the contribution of these interactions to auxilin function in vivo has not been tested.

Several lines of evidence support the role of Hsp70 and auxilin in uncoating CCVs in vivo. 1) Overexpression or depletion of the nonneuronal form of auxilin, cyclin G–associated kinase (GAK) causes a defect in receptor-mediated endocytosis (Umeda et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2005). 2) Disruption of the yeast ortholog of auxilin, SWA2, abrogates clathrin function and causes a defect in the disassembly process in vivo (Gall et al., 2000; Pishvaee et al., 2000). 3) RNAi knockdown of the auxilin homolog in Caenorhabditis elegans causes immobilization of intracellular clathrin and abrogates receptor-mediated endocytosis (Greener et al., 2001). 4) Injection of mutant auxilin lacking a functional J-domain into squid presynaptic terminals causes accumulation of CCVs and blocks neuronal transmitter release (Morgan et al., 2001; Augustine et al., 2006). 5) Overexpression of an ATPase-deficient Hsc70 in HeLa cells inhibits CCV uncoating and blocks transferrin receptor recycling (Newmyer and Schmid, 2001). 6) An Hsc70 point mutation in Drosophila melanogaster blocks endocytosis in larval Garland cells (Chang et al., 2002). These studies all support a model where auxilin plays a crucial role in regulating the function of Hsp70 in clathrin disassembly, presumably through the ability of auxilin to bind clathrin, recruit Hsp70 to the clathrin lattice, and stimulate its ATPase activity. The yeast system provides the opportunity to test the relative contribution of these auxilin functions in regulating clathrin disassembly in vivo through mutational analysis of the auxilin ortholog Swa2p.

Swa2p has a C-terminal J-domain and we had previously found that the N-terminal 287 amino acid fragment could interact with clathrin (Gall et al., 2000). Solution structural studies indicated that most of this clathrin-binding region is unstructured, except for a small segment that folds into a ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain that interacts with ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins (Chim et al., 2004). The function of this UBA domain in Swa2p is unknown, although it could mediate interaction with CCVs because monoubiquitination is an endocytic signal and many cargo proteins within CCVs are ubiquitinated (Hicke and Dunn, 2003). In addition, Swa2p contains three tetratricopeptide repeats within its TPR domain (Gall et al., 2000; Pishvaee et al., 2000), which consists of a degenerate 34-amino acid repeat in a tandem array that generally serves as a protein–protein interaction platform (D’Andrea and Regan, 2003). One major class of interaction mediated by TPR domains is with the highly conserved C-terminal EEVD of Hsp70 and Hsp90 (Scheufler et al., 2000). The Swa2p TPR domain has several consensus amino acid residues required to form a structure called the two-carboxylate clamp that binds to negatively charged side chains from the EEVD motif (Gall et al., 2000). Thus, Swa2p has two domains (TPR and J) with the potential to mediate interaction with Hsp70. In fact, a point mutation in the Swa2p TPR domain generates a partial loss of function allele (Gall et al., 2000), but we had not determined if this mutation perturbs Swa2p function in Hsp70-mediated clathrin disassembly. In this report, we define the CB motifs in Swa2p and assess the in vivo significance of the CB motifs, the TPR, and J-domains to regulation of clathrin disassembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Plasmids

The original swa2Δ strain, JX01 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 swa2Δ::kanr), was from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion collection. Because direct transformation of plasmids into JX01 caused a heterogeneous growth phenotype among transformants, a plasmid-shuffling strategy was used to overcome this epigenetic affect such that only phenotypically wild-type strains were transformed. JX01 was first mated to the wild-type BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) strain to generate the swa2Δ/SWA2 heterozygote, JX02. pSWA2-URA3 was then transformed into JX02 to make JX03, which was sporulated. MATα swa2Δ::kanr pSWA2-URA3 spores were selected on SD medium (synthetic medium plus dextrose) with G418 but lacking uracil. All isolates formed uniformly sized colonies indistinguishable from the wild-type strain at 30°C. One of the isolates, JX04 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 swa2Δ::kanr pSWA2-URA3) served as the swa2Δ shuffling strain for complementation tests. JX05 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 swa2Δ::kanr pSWA2-URA3 arf1Δ::HIS3) was generated by one-step gene disruption of ARF1 in JX04 as previously described (Gaynor et al., 1998). To follow GFP-tagged clathrin light chain in the presence of different swa2 alleles, diploid JX06 was generated by mating JX04 to a CLC1-GFP strain (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 CLC1-GFP) that was from the global GFP tagging collection (Huh et al., 2003). After random sporulation of JX06, spore JX07 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 swa2Δ::kanr pSWA2-URA3 CLC1-GFP) was selected in SD medium with G418 but lacking uracil and histidine.

For complementation tests, LEU2 plasmids (pRS315) harboring wild-type SWA2, swa2 mutant alleles, or no insert (empty plasmid) were transformed into the shuffling strains JX04, JX05, and JX07. Transformants were grown overnight in SD medium lacking leucine and then streaked onto 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates to select for the absence of pSWA2-URA3 but the presence of testing plasmids. Single colonies were selected once more on 5-FOA plate and these postshuffling strains were then used for complementation tests.

All swa2 N-terminal truncation alleles and internal deletion alleles were generated by overlap extension PCR (Ho et al., 1989) using pRS315-SWA2 (Gall et al., 2000) as the template in the first PCR reaction. Primer pairs for each PCR reaction used to generate DNA fragments containing SWA2 deletions are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Overlap extension PCR products were then digested by restriction enzyme indicated in Supplementary Table 3 and ligated with pRS315-SWA2 that was digested by the same restriction enzymes. For swa2ΔJ, pRS315-SWA2 was digested with PshAI and SmaI, and the plasmid containing 5’ sequence of SWA2 was self-ligated. 2μ plasmids carrying indicated SWA2 alleles were constructed by cloning NotI-BamHI SWA2 fragments from pRS315 plasmids into pRS425. The HPD→AAA mutant was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). GST fusion constructs were generated by PCR amplification of different SWA2 fragments using primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 1 that were engineered to include BamHI (5’) and EcoRI (3’) sites. The PCR products were then digested by BamHI and EcoRI and ligated in-frame into pGEX-2T vector that was also digested by the same enzymes. All constructs described above were verified by sequencing.

GST Fusion Protein Purification and GST Pulldown Assay

pGEX-2T plasmids fused with various Swa2p fragments were used to transform the BL21 Escherichia coli strain. The GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified following protocols from GST Gene Fusion System Handbook (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). GST fusion proteins were incubated with glutathione-agarose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min at room temperature. The resin was then washed three times with pH 7.4 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min each. A small portion of the bound GST fusion proteins were eluted by SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, stained by Simple Blue (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), scanned by the Odyssey infrared scanner and quantified by Odyssey application software (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) using a BSA dilution series run on the same gel as a standard.

A clarified yeast lysate was used as the source of clathrin in GST pulldown experiments. Wild-type yeast cells, 50 OD600/ml BY4742, were first spheroplasted and then lysed in buffer A (0.1 M MES, pH 6.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT, 3 mM NaN3, 1% [vol/vol] yeast protease inhibitor cocktail; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Crude lysate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used as the clarified lysate. Total protein concentration of the clarified lysate was 5–8 mg/ml, as measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Sigma). Immobilized GST fusion protein, 0.5 nmol of each, was incubated with 1 ml of clarified yeast lysate for 1 h at 4°C on a rotating platform. Unbound proteins were separated from the resin by centrifugation. The resin with bound protein was then washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 min each. Clathrin heavy chain in the bound and unbound fractions was detected on Western blots using a monoclonal antibody (Gift from Sandra K. Lemmon, University of Miami), and the appropriate secondary antibody was conjugated with either Alexa 680 or IR800 fluorophore (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA). Blots were visualized using an Odyssey infrared scanner unless otherwise specified, and Odyssey Application Software was used to quantify total clathrin present in each fraction.

Growth and α-Factor Halo Assays

Postshuffling strains were grown at 30°C in SD −Leu medium to midlog phase. Cells were harvested and resuspended in sterile water at 1 OD600/ml, and 3 μl of a 10-fold serial dilution was spotted onto YPD plates and incubated at 30 or 37°C for 24–36 h before photographing. Secretion of biologically active α-factor was determined as previously described (Hopkins et al., 2000) with the following modifications. Postshuffling strains harboring different SWA2 alleles were grown at 30°C in SD −Leu medium to midlog phase. Cells were harvested and resuspended in sterile water at 1 OD600/ml. Cell suspension, 5 μl of each, was spotted on plates containing the supersensitive strain RC634 (MATa sst1-3 rme ade1-2 ura1 his6 met1 can1 cyh2 GAL; Chan, 1977) in the top agar and incubated at 30°C for 2 d.

Clathrin Distribution Assay

The distribution of clathrin between assembled and free triskelia forms was determined as previously described (Gall et al., 2000) with the following modifications. Protein in the high-speed supernatant (S150) was first precipitated with 10% TCA on ice for 30 min and then resolubilized in 5% SDS, 0.1 N NaOH. The high-speed pellet (P150) was also solubilized in 5% SDS, 0.1 N NaOH. Total protein concentration for both fractions was measured by the BCA method, and 8 μg of total protein from each fraction was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Clathrin was detected by Western blot and quantified as described above.

RESULTS

Clathrin-binding Motifs in Swa2p

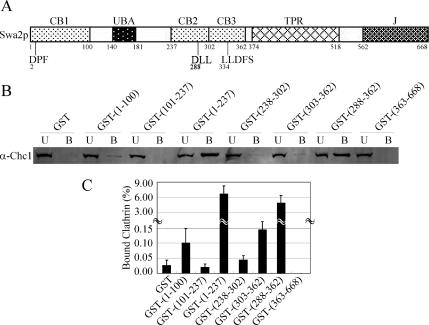

We had previously found that the N-terminal 287-amino acid fragment of Swa2p binds clathrin (Gall et al., 2000), but as described below, deletion of these sequences has little impact on Swa2p function in vivo. Therefore, we sought to better define the sequences responsible for interaction of Swa2p with clathrin. Swa2p contains several sequence motifs that could potentially bind clathrin, a DPF at the N-terminus, a DLL near the middle of the protein, and a degenerate clathrin box I motif, LLDFS, between the DLL sequence and TPR domain (Figure 1A). In addition, the UBA domain could also potentially recruit Swa2p to CCVs through its interaction with ubiquitinated cargo proteins. There are no known CB motifs present in the C-terminal fragment 363–668.

Figure 1.

Swa2p binding to clathrin is mediated by several weak interactions. (A) Diagram of Swa2p domains and fragments with clathrin-binding (CB) activity. (B) GST and GST-Swa2p fragments, 0.5 nmol each, were immobilized on glutathione-agarose and incubated with clarified yeast whole cell lysate as described in Materials and Methods. 0.5% of the total unbound (U) proteins and 15% of the total bound (B) proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the amount of clathrin heavy chain in both fractions was visualized by Western blot. (C) The total clathrin present in each fraction was quantified by Odyssey Application Software (LI-COR). Bound clathrin (%) was calculated as bound clathrin divided by total clathrin in both fractions (n = 3; error bars, ±SD).

To define sequences within Swa2p with the capacity to interact with clathrin, we performed a complete scan of Swa2p for fragments with CB activity using a GST pulldown assay from yeast lysate. GST fusions with Swa2p fragments 1–100 (CB1), 238–302 (CB2), and 303–362 (CB3), containing each of the three putative CB motifs, were able to pull down more clathrin than GST alone (Figure 1, B and C), although each individual fragment bound clathrin very weakly. The UBA-containing fragment 101–237 did not bind clathrin (Figure 1, B and C). But strikingly, fragment 1–237, containing both CB1 and UBA, pulled down 50–60 times more clathrin than CB1 alone (Figure 1C). Similarly, a fragment containing both the DLL and LLDFS motifs (288–362) interacted avidly with clathrin (Figure 1C). Finally, there was no detectable interaction between clathrin and the C-terminal fragment (363–668) bearing the TPR and the J-domains. Therefore, we conclude that there are a number of weak interactions between clathrin and short unstructured motifs in the N-terminus of Swa2p. In addition, these results also suggest that the UBA domain may contribute to the recruitment of Swa2p to CCVs.

To further address whether the UBA domain or other sequences in the 101 – 237 segment facilitates clathrin interaction in combination with CB1, additional GST fusion proteins were prepared containing amino acids 1–140 (without the UBA) and 1–181 (with the UBA) and tested for clathrin binding. The 1–140 fragment bound much more clathrin than fragment 1–100, and no additional clathrin was pulled down with fragments 1–181 or 1–237 (Supplementary Figure 1). Therefore, an additional CB activity maps to amino acids 101–140 and no contribution to clathrin interaction was observed for the UBA domain. For these pulldown experiments, yeast cytosol centrifuged at high speed to remove CCVs was used as a source for free clathrin triskelia. Comparable data were obtained using clathrin-coated vesicles in the high-speed pellet (unpublished observations). Thus, these Swa2p-clathrin interactions occur with free triskelia and are not enhanced or bridged by other components of CCVs. In addition, mass spectrometry analysis of proteins copurified with Swa2p (visible by colloidal blue staining) using tandem affinity purification (TAP) identified clathrin, Ssa and Ssb (Hsc70) proteins and a few abundant proteins that commonly contaminate TAP purifications (such as ribosomal proteins). No other clathrin binding protein was present in sufficient quantity to have bridged the interaction with clathrin, and so it is likely that the Swa2p-clathrin interactions assayed here are direct (unpublished observations).

Requirement for Swa2p CB Motifs In Vivo

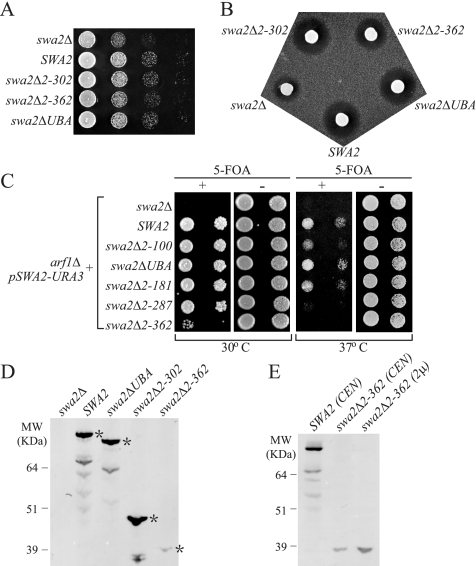

To test the function of the CB motifs in vivo, we generated a series of Swa2p N-terminal truncations up to amino acid residue 362 (swa2Δ2-100, swa2Δ2-138, swa2ΔUBA, swa2Δ2-181, swa2Δ2-287, swa2Δ2-302, and swa2Δ2-362), which progressively eliminated all three biochemically defined CB regions as well as the UBA domain. These swa2 alleles were transformed into a swa2Δ strain and tested for complementation of the swa2Δ growth defect. Surprisingly, all N-terminal truncations up to amino acid 302 complemented the swa2Δ growth defect as well as wild-type SWA2 (data shown for swa2Δ2-302 only), whereas swa2Δ2-362 partially complemented swa2Δ in the growth assay (Figure 2A), indicating that Swa2Δ2-362 protein has partial function in vivo even though it lacks all known CB motifs. In addition, deletion of the UBA domain did not appear to affect Swa2p function. Most of the truncated Swa2 proteins were expressed at a level comparable to wild-type Swa2p (Figure 2D and unpublished observations). However, the Swa2Δ2-362 protein expressed from a CEN plasmid was poorly detected on the Western blot (Figure 2D). It is not clear if this is due to instability of Swa2Δ2-362 or the loss of major epitopes for the polyclonal antibodies used for detection. Overexpression of swa2Δ2-362 from a multicopy (2μ) plasmid yielded threefold more protein (Figure 2E), but overexpression did not improve its ability to complement the swa2Δ growth defect (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Deletion of the UBA domain and CB motifs only partially perturbs Swa2p function in vivo. Single-copy plasmids carrying the SWA2 N-terminal deletion alleles indicated were transformed into strain JX04 (swa2Δ) and tested for complementation of growth (A) and α-factor halo (B) defects in comparison to empty plasmid (swa2Δ) and wild-type SWA2. Only the largest deletion, swa2Δ2-362, exhibited a partial loss of activity. (C) Complementation of swa2Δ arf1Δ synthetic lethality. Plasmids carrying the indicated SWA2 alleles were transformed into strain JX05 (swa2Δ arf1Δ pSWA2-URA3), and transformants were tested for growth with (+) or without (−) 5-FOA, which selects for loss of pSWA2-URA3. Growth in the presence of 5-FOA indicates complementation of the swa2Δ arf1Δ synthetic lethality. (D–E) Western Blots showing wild-type and mutant Swa2 proteins from whole cell lysates. Asterisks indicate the position of full-length proteins.

These truncation alleles were also tested for complementation of swa2Δ defect in α-factor processing. Normal clathrin function is required for correct protein sorting at the TGN; thus swa2Δ causes mislocalization of TGN resident proteases that cleave pro-α-factor to its mature form (Payne and Schekman, 1989). To assay for secretion of mature α-factor, the swa2 mutants were spotted onto a lawn of MATa cells that are supersensitive to the pheromone. Mature α-factor induces a G1 arrest in the lawn cells producing a zone of growth inhibition, or halo, around patches of cells secreting α-factor. Pro-α-factor is not biologically active and so the size of the halo depends on the amount of mature α-factor secreted. Because swa2Δ has a defect in secreting mature α-factor, it produced a much smaller halo than the wild-type strain (Figure 2B). The hypomorphic nature of swa2Δ2-362 was more obvious in the halo assay with a halo size intermediate between SWA2 and swa2Δ, whereas any smaller truncation complemented as well as wild-type SWA2 (Figure 2B and unpublished observations).

The SWA2 gene was originally identified in a screen for mutations synthetically lethal with arf1 (Chen and Graham, 1998), a small GTP-binding protein that recruits clathrin to the TGN. For a more sensitive functional assay, the truncation alleles were tested for complementation of arf1Δ swa2Δ synthetic lethality using a plasmid-shuffling strategy. An arf1Δ swa2Δ strain carrying wild-type SWA2 on a URA3 plasmid was transformed with a LEU2 plasmid harboring the indicated truncation allele. Cells capable of losing pSWA2-URA3 were selected on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) to assess the ability of each swa2 truncation to support growth. At 30°C, again only swa2Δ2-362 showed a synthetic growth defect with arf1Δ, although not as severe as the empty plasmid (swa2Δ) control (Figure 2C). However, when these strains were incubated at 37°C to make the conditions more stringent, we observed an increased dependency on CB1 and CB2 (Figure 2C, compare swa2Δ2-100 and swa2Δ2-287 to SWA2 at 37°C). Interestingly, the growth of swa2ΔUBA was slightly better than that of SWA2 at 37°C (Figure 2C), suggesting the UBA domain may exert a negative influence at this temperature. The same pattern was also true for swa2Δ2-100 and swa2Δ2-181, which differ in the presence or absence of the UBA domain, respectively (Figure 2C). Overall, we conclude that the interaction with clathrin is important for full function of Swa2p in vivo, although Swa2p can tolerate the loss of all biochemically defined CB motifs with compromised activity.

Requirement for Swa2p CB Motifs in Regulating Clathrin Dynamics In Vivo

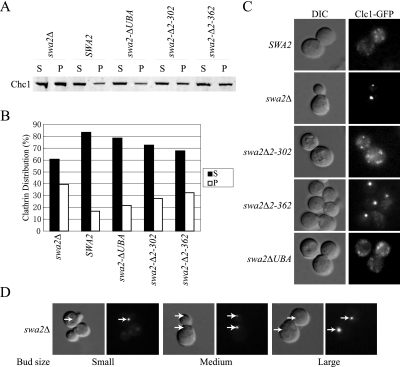

Because the truncation of all known N-terminal CB motifs did not abolish all Swa2p function in vivo, we further examined the influence of truncations on clathrin dynamics. There are two major pools of clathrin in the cell: a pool of free triskelia that is cytosolic and fractionates in a high-speed supernatant (S150) after centrifugation of cell lysates and a pool of assembled clathrin that fractionates in a high-speed pellet (P150). From a wild-type strain, the majority of total clathrin fractionates in the S150 indicative of free triskelia, whereas the pool of assembled clathrin (P150) from the swa2Δ strain increased significantly (Figure 3, A and B). As previously shown, these data indicate a Swa2p requirement for clathrin disassembly. By this assay we observed a graded response to the truncation series, with more clathrin present in the P150 as more known CB motifs were removed (Figure 3, A and B and unpublished data). swa2Δ2-362 showed the most severe phenotype among all the SWA2 N-terminal truncation alleles, but still not as severe as swa2Δ in this clathrin distribution assay (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Requirements for Swa2p CB motifs and UBA domain in regulating clathrin dynamics in vivo. (A) The same set of SWA2 N-terminal deletions described in Figure 2 was tested for complementation of the swa2Δ defect in clathrin disassembly by the clathrin distribution assay (see Materials and Methods). Clarified yeast lysates were centrifuged at 150,000 × g to generate a pellet (P) fraction containing assembled clathrin and a supernatant (S) fraction containing free triskelia. Total protein, 8 μg for each fraction, was Western-blotted to visualize the clathrin heavy chain (Chc1p). (B) For quantification of the data shown in A, band intensities were corrected for the volume of the pellet and supernatant fractions to determine the total amount of clathrin in each fraction, which was divided by the sum of clathrin in the P and S fractions to give the % distribution. (C) Complementation of the swa2Δ defect in regulating the dynamics of the clathrin light chain fused with GFP (Clc1-GFP) in living cells. The same set of plasmids carrying SWA2 N-terminal deletions was used to transform strain JX07 (swa2Δ Clc1-GFP). Transformants were selected on 5-FOA plates for the loss of pSWA2-URA3 and then imaged for Clc1-GFP fluorescence. (D) Appearance of Clc1-GFP puncta in medium-budded swa2Δ (JX07) cells. Representative cells with different bud sizes are shown and arrows indicate the position of the puncta.

Next, we examined the impact of these truncation mutants on clathrin distribution in living cells expressing a clathrin light-chain GFP fusion protein (Clc1-GFP) as the sole source of light chain. These cells grow at wild-type rates, suggesting that Clc1-GFP is functional. In wild-type cells, Clc1-GFP fluorescence is diffusely spread throughout the cytosol, representing the free triskelia and CCVs (Figure 3C), with a number of small puncta that likely represent assembled clathrin on the TGN or endosomes. Indeed, most of the Clc1-GFP puncta in wild-type cells colocalizes with Sec7-RFP, a marker for the TGN further suggesting Clc1-GFP is functional (Supplementary Figure 2). Strikingly, Clc1-GFP coalesces into a single, large punctum with very little diffuse cytosolic fluorescence in swa2Δ cells, indicating a strong defect in the regulation of clathrin dynamics (Figure 3, C and D). The truncation of Swa2p up to amino acid 302, removing CB1, UBA, and CB2, complemented the Clc1-GFP aggregation phenotype of swa2Δ (Figure 3C). However, the truncation missing all known CB motifs, swa2Δ2-362, failed to complement and appeared much like swa2Δ. Therefore, we conclude that the CB activity of the Swa2p N-terminus has an essential function in regulating clathrin dynamics in vivo. In addition, a single CB motif appears to be sufficient to support nearly wild-type Swa2p function in vivo.

Interestingly, the Clc-GFP punctum appeared to be inherited in a cell cycle–dependent manner. New clathrin puncta appeared in daughter cells when the bud reached ∼50% the diameter of the mother cell (Figure 3D). This suggests that the clathrin assembly (or aggregation) is nucleated on a specific structure that is inherited in a cell cycle–controlled pattern. It is not clear if the localization of Clc1-GFP reflects the distribution of endogenous clathrin in swa2Δ because immunological detection of clathrin (untagged) in cells depleted of Swa2p showed increased membrane association of clathrin at the expense of diffuse cytosolic fluorescence, but did not show coalescence to a single spot (Pishvaee et al., 2000). Therefore, it is possible that Clc1-GFP may exaggerate the defect in clathrin disassembly exhibited by swa2Δ. However, this phenotype provides a valuable assay for Swa2p function in a living cell because the extent of Clc1-GFP coalescence caused by the swa2 allelic series correlates well with the increase in assembled clathrin (untagged) measured by centrifugation.

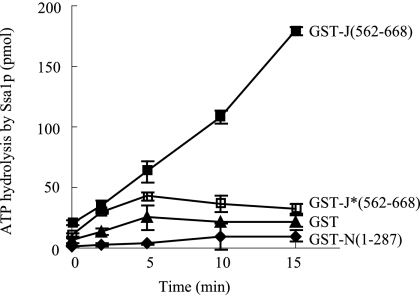

Requirement for Swa2p TPR and J-Domains In Vivo

All Hsp40/DnaJ family members contain a signature J-domain with a nearly invariant HPD motif that is critical for interaction with Hsc70 both physically and functionally (Hennessy et al., 2005). To determine if the HPD motif in the Swa2p J-domain is also required for stimulating Hsp70 ATPase activity, we mutated the HPD to AAA, fused both the mutant and wild-type J-domains to GST, and assayed each recombinant fusion protein in vitro for stimulation of Ssa1p, a yeast cytosolic Hsp70. Purified Ssa1p and indicated GST fusions were incubated in the presence of ATP at 30°C for the times indicated in Figure 4, and ATPase activity was assessed by production of free phosphate. GST alone and GST-N(1-287), lacking both the TPR and the J-domain, served as negative controls. As shown in Figure 4, wild-type GST-J(562-668) robustly stimulated ATP hydrolysis by Ssa1p, but the HPD→AAA mutant GST-J*(562-668) was only slightly more active than the negative controls, indicating the HPD→AAA mutant is defective for J-domain function as expected.

Figure 4.

The HPD→AAA mutation greatly reduced the ability of the Swa2p J-domain to stimulate the ATPase activity of Ssa1p (yeast Hsp70). GST, GST-N(1-287), GST-J(562-668), or GST-J*(562-668) (1 μM each, asterisk indicates the HPD→AAA mutant) was mixed with 0.5 μM Ssa1p in 10 μl of buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) containing 100 μM ATP and [γ-32P]ATP. Samples were harvested at the indicated times, and free phosphate was separated from ATP by TLC. ATP hydrolysis was quantified as described previously (Lu and Cyr, 1998; n = 3; error bars, ±SD).

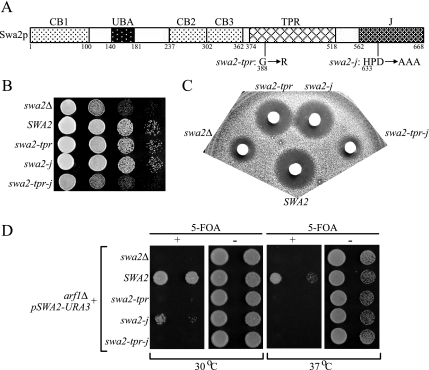

We anticipated that mutation of the HPD motif in the J-domain of Swa2p (to produce swa2-j, Figure 5A) would interrupt the function of Swa2p as a cochaperone and render it nonfunctional in vivo. But surprisingly, the swa2-j allele complemented swa2Δ defects in both the growth and halo assays (Figure 5, B and C), suggesting that either the J-domain is not required for Swa2p function in vivo or swa2-j is a hypomorphic allele. In fact, swa2-j does cause a growth defect when combined with arf1Δ (Figure 5D) and so the HPD→AAA mutation causes a partial loss of function in vivo.

Figure 5.

Requirements of SWA2 TPR and J domains for Swa2p function in vivo. (A) Diagram of SWA2 TPR and J-domain mutant alleles. (B–D) The same complementation tests as described in the legend to Figure 2 were performed for the indicated SWA2 alleles. Both swa2-j and swa2-tpr mutants provided nearly wild-type function in the growth and halo assays, whereas the swa2-tpr-j double mutant were inactive (B and C). The hypomorphic nature of the single mutants is clearly seen in the arf1Δ synthetic lethality test (D).

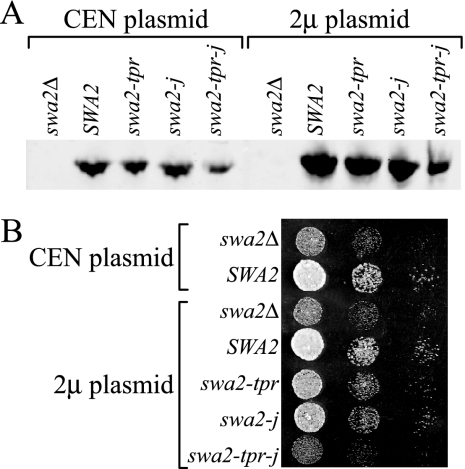

The TPR domain of Swa2p is conserved well with the TPR1 domain in Hsp70/Hsp90-organizing protein (Hop) that interacts specifically with Hsp70 (Gall et al., 2000; Scheufler et al., 2000), so we considered the possibility that the TPR and J-domains in Swa2p are redundant for interaction with Hsp70. For example, Sti1p, the yeast homolog of Hop, and the TPR-containing protein Cns1p potently stimulate Hsp70 ATPase activity even though these proteins do not contain a J-domain (Wegele et al., 2003; Hainzl et al., 2004). The TPR mutant allele, swa2-tpr (Figure 5A) was originally isolated from the arf1 synthetic lethal screen, but it did not perturb growth of strains carrying wild-type ARF1 (Gall et al., 2000). As expected, the swa2-tpr allele complemented the swa2Δ growth defect (Figure 5B) and was synthetically lethal with arf1Δ (Figure 5D) in the strain background used in this study. In addition, swa2-tpr showed a slight defect by the halo assay (Figure 5C) and interestingly, the halo and synthetic lethal tests indicate that swa2-tpr has a more impaired function in vivo than swa2-j. Importantly, when we combined the TPR G388R mutation with the HPD→AAA mutation, the double mutant completely failed to complement swa2Δ in the growth, halo, or synthetic lethal assays (swa2-tpr-j, Figure 5, B–D). Expression of Swa2-tpr-j protein is reduced relative to wild-type Swa2p or either single mutant protein (Figure 6A), raising the possibility that the loss of function is due to insufficient protein. Overexpression of the double mutant from a multicopy (2μ) plasmid yielded protein comparable to wild-type SWA2 expressed from a low-copy (CEN) plasmid (Figure 6A). However, the overexpressed swa2-tpr-j still failed to complement the swa2Δ growth defect (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

swa2-tpr-j loss of function is not due to reduced expression. (A) SWA2 alleles were expressed from either single-copy (CEN) or multicopy (2μ) plasmids, and 0.5 OD600 cell equivalents were immunoblotted using a polyclonal antibody against Swa2p. (B) Multicopy SWA2 alleles were tested for complementation of the swa2Δ growth defect. Multicopy expression of swa2-tpr-j yields comparable protein to wild-type Swa2p (CEN expression), but it still failed to complement the swa2Δ growth defect.

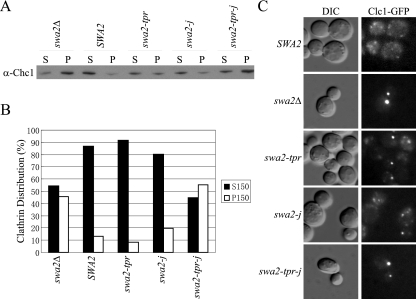

Influence of Swa2p TPR and J-Domains on Clathrin Dynamics In Vivo

We further explored the potential redundancy between Swa2p TPR and J-domains in regulating clathrin dynamics in vivo. Both the swa2-tpr and swa-j mutants were partially defective in clathrin disassembly in the fractionation assay, but again the swa2-tpr-j double mutant failed to complement and accumulated an equivalent amount of assembled clathrin in the P150 as swa2Δ (Figure 7, A and B). We next examined the Clc1-GFP distribution in the presence of these alleles. The swa2-tpr and swa-j mutants exhibited a phenotype intermediate between wild-type and swa2Δ (Figure 7C). Large clathrin aggregates that were absent in wild-type cells could be detected in both the swa2-tpr and swa2-j mutants. However, the fluorescent intensity of these aggregates was weaker than that of swa2Δ, and smaller puncta with diffuse cytosolic fluorescence were also present. In contrast, the swa2-tpr-j mutant was indistinguishable from swa2Δ. Consistent with the cell fractionation data, mutation of both the TPR and the J-domain causes a complete loss of function of Swa2p in clathrin-GFP disassembly. The loss-of-function phenotype of swa2-tpr-j relative to the single mutants, suggests that both the TPR and the J-domain are involved in the same process, presumably harnessing Hsp70 for clathrin uncoating.

Figure 7.

Swa2p TPR and J-domain requirements for regulating clathrin dynamics in vivo. (A and B) Strains carrying the indicated SWA2 alleles were tested for complementation of the swa2Δ clathrin disassembly defect as described in the legend to Figure 3. (C) Complementation of the Clc1-GFP coalescence phenotype of swa2Δ (see Figure 3 legend for details).

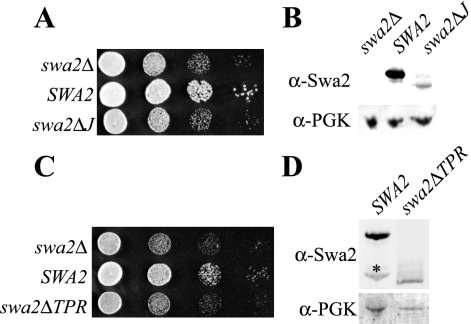

The Swa2p J and TPR Domains Are Not Functionally Interchangeable

The results described above suggest that TPR and J-domains are functionally redundant, but this conclusion relies on the assumption that the G388R (swa2-tpr) and HPD→AAA (swa2-j) mutations completely inactivate these two domains. However, we found that a J-domain deletion (swa2ΔJ) fails to complement the swa2Δ defects in growth (Figure 8A) or Clc1-GFP distribution (unpublished observation). In addition, Pishvaee et al. (2000) also reported that deletion of the J-domain inactivates Swa2p function in vivo. The swa2ΔJ allele we produced is expressed poorly, but the J-domain deletion generated by Pishvaee et al. (2000) was reported to be stable. Therefore, it is likely that the J-domain is required for function, rather than stability, of this modular protein. If this is the case, then the HPD→AAA mutation does not eliminate J-domain function in vivo. Moreover, deletion of the TPR domain (swa2ΔTPR) also caused a complete loss of function (Figure 8C). After normalizing for the loading control (PGK), the Swa2ΔTPR protein is expressed at ∼50% the level of wild-type Swa2p and so it is reasonably stable (Figure 8D). Likewise, the G388R mutant is also hypomorphic for the activity of the TPR domain. Therefore, these data suggest that each domain is indispensable for the ability of Swa2p to regulate Hsc70 activity in vivo.

Figure 8.

Deletion of either the TPR or the J-domain eliminates Swa2p function. Plasmid carrying swa2ΔJ (A) or swa2ΔTPR (B) was tested for complementation of the swa2Δ growth defect. (C and D) 0.5 OD600 cell equivalents were subjected to Western blotting as described above. The asterisk indicates a degradation product of Swa2p.

DISCUSSION

Prior biochemical studies suggest a model for auxilin function whereby multiple CB motifs within an unstructured domain mediate interaction with assembled clathrin coats, whereas the J-domain recruits Hsc70-ATP and stimulates its ATPase activity. The ADP-bound Hsc70 would then interact tightly with clathrin and induce a conformational change that causes release of triskelia from the lattice (Ungewickell et al., 1995; Gruschus et al., 2004). In support of this model, we show here that the CB motifs in yeast auxilin, Swa2p, play a critical role in clathrin disassembly in vivo. The Swa2p CB activity mapped to three regions (CB1–CB3), each containing a CB motif (DPF, DLL, LLDFS) in the mostly unstructured N-terminal half of this protein. Individually, these motifs interact weakly with clathrin from cell lysates, but in combination they produce an avid interaction. In addition, amino acids 101–140 significantly contribute to clathrin interaction even though these sequences do not contain a previously characterized CB motif, and we could not detect an interaction between these sequences and clathrin unless another CB motif was present. Characterization of this potentially novel CB motif is underway. Multivalent interactions of moderate strength appear to be a common theme for many clathrin-interacting proteins, suggesting this mode of binding is necessary for the dynamic regulation of clathrin assembly and disassembly. However, we were surprised to find that an N-terminal truncation removing nearly half of the protein and bearing only a single CB motif (CB3) retains most Swa2p function in vivo. Additional deletion of CB3 strongly abrogates Swa2p function in regulating clathrin dynamics. These data suggest that a single CB motif is sufficient for yeast auxilin to recruit Hsc70 onto clathrin lattices.

Also surprising was the observation that a fragment containing only the TPR and J-domains can partially complement swa2Δ growth defects. This suggests that either the C-terminal TPR-J fragment has a CB activity (mediated by a novel clathrin-interaction motif) that went undetected in the pulldown experiments or that Swa2p has other cellular functions besides its role in regulating clathrin dynamics. In support of the latter possibility, SWA2 was identified in a genetic screen for ER inheritance mutants (Du et al., 2001), and so it will be interesting to test if swa2Δ2-362 complements the ER inheritance defect of swa2Δ. The function of the UBA domain in Swa2p is still unclear, because it does not appear to contribute to clathrin interaction and deletion of this domain does not perturb Swa2p function in vivo.

The most unexpected observation of this work is that mutation of the highly conserved HPD motif (HPD→AAA) in the Swa2p J-domain produces only a mild, partial loss of function phenotype in vivo. In contrast, the same HPD→AAA mutation strongly abrogates the ability of a GST-J fusion protein to stimulate Hsc70 ATPase activity in vitro. However, the J-domain is indispensable for Swa2p in vivo because complete deletion of this domain causes a complete loss of function. Therefore, with the caveat that deletion of the J-domain from this modular protein does not disrupt the structure/function of the adjacent TPR domain, we conclude that the HPD→AAA J-domain retains significant function in vivo. Perhaps the limited activity of the HPD→AAA mutant J observed in the Hsc70 ATPase stimulation assay is sufficient to allow function in vivo. For the mitochondrial J protein Jac1p, residual Hsc70 stimulating activity of the HPD→AAA mutant can only be observed in the presence of substrate (Dutkiewicz et al., 2004). It will be interesting to determine if addition of pure clathrin to the assay allows greater activity of the mutant Swa2p J-domain. Even though the TPR domain is only found in fungal auxilin orthologues, this domain is also indispensable for Swa2p function in vivo. Deletion of the TPR domain renders Swa2p completely nonfunctional and therefore the G388R (swa2-tpr) point mutation, which retains significant function, is hypomorphic for function of the TPR domain. These observations indicate that the TPR and J-domains, each with the capacity to interact with Hsc70, are not functionally interchangeable.

Importantly, the activity of the crippled J-domain (HPD→AAA) absolutely requires a fully functional TPR domain. Combination of the HPD→AAA and G388R hypomorphic mutations (swa2-tpr-j) totally abolished Swa2p function. This strongly suggests that the TPR and J-domains are collaborating to regulate the activity of Hsc70 in clathrin disassembly. We can envision multiple mechanisms for how this molecular collaboration may be achieved. For example, there may be an intramolecular interaction between the TPR and J-domains that is essential for stable J-domain interaction with Hsc70, or the TPR domain may interact with other regulatory proteins, such as kinases or phosphatases, required for J-domain function. However, we favor a model where both the TPR and J-domains contact Hsc70 and this bipartite interaction is essential for regulation of Hsc70 ATPase activity. This latter model is based on the conservation of the Swa2p TPR domain with TPR domains that directly interact with the C-terminal EEVD sequences of Hsc70s and the requirement for a bipartite interaction of another Hsp40 member, Sis1p, for interaction with Hsc70 (Qian et al., 2002; Aron et al., 2005). Although Sis1p does not have a TPR domain, interaction between a C-terminal domain of Sis1p with the C-terminus of Hsc70p is needed to provide full Sis1p/Hsc70 activity in maintenance of a yeast prion (Lopez et al., 2003; Aron et al., 2005). Unfortunately, the Swa2p TPR domain does not express well in E. coli when fused to either GST or a hexahistidine tag, and we have not been able to detect an interaction between the TPR domain and the C-terminus of Hsc70. In addition, a stable GST fusion bearing the CB3, TPR, and J-domains (a fragment that is functional in vivo) fails to pulldown clathrin or stimulate the ATPase activity of Hsc70 (unpublished observations). This result may suggest that the TPR domain mediates an intramolecular interaction regulated by a eukaryotic posttranslational modification, but we cannot rule out the more trivial possibility that this fragment misfolds in E. coli.

In conclusion, although biochemical confirmation is not at hand, the genetic results strongly suggest that the Swa2p TPR domain regulates Hsc70 activity in clathrin uncoating. The potential second-site interaction with Hsp70, in addition to the J-domain/Hsp70 interaction, may provide an extra handle for stable association. For example, the potential TPR–Hsp70 interaction could locally concentrate Hsp70 such that even a crippled J-domain (HPD→AAA mutant) can function in vivo. This is consistent with an induced-fit model, which suggests that the HPD motif is not the catalytic unit for Hsp70 stimulation, but that it orients helix 2 and 3 of J-domains for productive interaction with Hsp70 (Huang et al., 1999; Berjanskii et al., 2002; Landry, 2003). The TPR-Hsp70 interaction may facilitate this orientation even in the absence of the HPD motif. Our data also indicate that the J-Hsc70 interaction is insufficient to mediate clathrin disassembly in the absence of the TPR domain. Perhaps the J-Hsc70 interaction alone is too weak to be maintained through multiple cycles of ATP hydrolysis and substrate transfer. Deletion of the GAK J-domain disrupts the function of this nonneuronal auxilin in vivo (Zhang et al., 2005), but it will be interesting to determine if mammalian auxilins, which lack TPR domains, require the HPD motif to regulate Hsc70 in vivo.

Although TPR and J-domains are commonly found in proteins that regulate Hsp70 and Hsp90, it is uncommon to find both domains in a single protein. Another example of a TPR-J protein is P58IPK, an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, protein kinase R (PKR; Melville et al., 1997), which upon activation by double-stranded RNA phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 2α to attenuate protein synthesis (Taylor et al., 2005). P58IPK also interacts with and inhibits the PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) that phosphorylates eIF2α as part of the ER stress response (Yan et al., 2002a). In an important parallel to our studies, mutation of the P58IPK HPD motif to AAA does not significantly abrogate the ability of P58IPK to inhibit PKR in vivo (Yan et al., 2002b). In this case, a complete deletion of the J-domain was not tested and so it is not known if the mutant J-domain retains some function in vivo that is supported by the TPR domain. Therefore, to our knowledge, the current work with Swa2p provides the first example of collaborative regulation of Hsp70 function by TPR and J-domains contained within a single cochaperone.

Another fascinating observation made here is the behavior of a clathrin-GFP fusion in the swa2Δ strain. All of the visible clathrin-GFP coalesces into a single focus in the swa2Δ mother cell, reminiscent of the insoluble, prion state of Rnq1-GFP, [RNQ+] (Sondheimer and Lindquist, 2000). In addition, the Clc1-GFP aggregates appear to be “inherited” into the bud, resembling another key feature of yeast prions. Moreover, Hsp70 and cochaperones are required for regulation of both clathrin dynamics and yeast prion propagation (Newnam et al., 1999; Jung et al., 2000; Jones and Masison, 2003). For example, overexpression of Sis1p or Ydj1, two other Hsp40 cochaperones with Hsp70, or Sti1p, the yeast homolog of the TPR cochaperone Hop in mammals, eliminate a variant of the yeast prion ψ+ (Kryndushkin et al., 2002). It will be interesting to further examine the nature of the Clc1-GFP aggregates and determine if there are any non-Mendelian patterns for inheritance of these structures, if clathrin coalesces onto a specific cellular structure, and if the aggregates disperse rapidly upon introduction of Swa2p into these cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Douglas Cyr for purified Ssa1p and advice during the course of this work, Sandra Lemmon for the monoclonal antibodies against the clathrin heavy chain, and Susan Wente for the CLC1-GFP strain. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM62367) and National Science Foundation (MCB0543724) to T.R.G.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0106) on May 10, 2006.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

REFERENCES

- Aron R., Lopez N., Walter W., Craig E. A., Johnson J. In vivo bipartite interaction between the Hsp40 Sis1 and Hsp70 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;169:1873–1882. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine G. J., Morgan J. R., Villalba-Galea C. A., Jin S., Prasad K., Lafer E. M. Clathrin and synaptic vesicle endocytosis: studies at the squid giant synapse. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:68–72. doi: 10.1042/BST0340068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch W., Prasad K., Greene L., Eisenberg E. Auxilin-induced interaction of the molecular chaperone Hsc70 with clathrin baskets. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4303–4308. doi: 10.1021/bi962727z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjanskii M., Riley M., Van Doren S. R. Hsc70-interacting HPD loop of the J domain of polyomavirus T antigens fluctuates in ps to ns and micros to ms. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;321:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00631-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J. S., Glick B. S. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 2004;116:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky F. M., Chen C. Y., Knuehl C., Towler M. C., Wakeham D. E. Biological basket weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2001;17:517–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R. K. Recovery of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating-type a cells from G1 arrest by alpha factor. J. Bacteriol. 1977;130:766–774. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.766-774.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H. C., Newmyer S. L., Hull M. J., Ebersold M., Schmid S. L., Mellman I. Hsc70 is required for endocytosis and clathrin function in Drosophila. J. Cell. Biol. 2002;159:477–487. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell T. G., Welch W. J., Schlossman D. M., Palter K. B., Schlesinger M. J., Rothman J. E. Uncoating ATPase is a member of the 70 kilodalton family of stress proteins. Cell. 1986;45:3–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-Y., Graham T. R. An arf1Δ synthetic lethal screen identifies a new clathrin heavy chain conditional allele that perturbs vacuolar protein transport. Genetics. 1998;150:577–589. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chim N., Gall W. E., Xiao J., Harris M. P., Graham T. R., Krezel A. M. Solution structure of the ubiquitin-binding domain in Swa2p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proteins. 2004;54:784–793. doi: 10.1002/prot.10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea L. D., Regan L. TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Pypaert M., Novick P., Ferro-Novick S. Aux1p/Swa2p is required for cortical endoplasmic reticulum inheritance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2614–2628. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutkiewicz R., Schilke B., Cheng S., Knieszner H., Craig E. A., Marszalek J. Sequence-specific interaction between mitochondrial Fe-S scaffold protein Isu and Hsp70 Ssq1 is essential for their in vivo function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29167–29174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotin A., Cheng Y., Grigorieff N., Walz T., Harrison S. C., Kirchhausen T. Structure of an auxilin-bound clathrin coat and its implications for the mechanism of uncoating. Nature. 2004;432:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall W. E., Higginbotham M. A., Chen C., Ingram M. F., Cyr D. M., Graham T. R. The auxilin-like phosphoprotein Swa2p is required for clathrin function in yeast. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor E. C., Chen C.-Y., Emr S. D., Graham T. R. ARF is required for maintenance of yeast Golgi and endosome structure and function. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:653–670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greener T., Grant B., Zhang Y., Wu X., Greene L. E., Hirsh D., Eisenberg E. Caenorhabditis elegans auxilin: a J-domain protein essential for clathrin-mediated endocytosis in vivo. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2001;3:215–219. doi: 10.1038/35055137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greener T., Zhao X., Nojima H., Eisenberg E., Greene L. E. Role of cyclin G-associated kinase in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles from non-neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:1365–1370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruschus J. M., Greene L. E., Eisenberg E., Ferretti J. A. Experimentally biased model structure of the Hsc70/auxilin complex: substrate transfer and interdomain structural change. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2029–2044. doi: 10.1110/ps.03390504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainzl O., Wegele H., Richter K., Buchner J. Cns1 is an activator of the Ssa1 ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:23267–23273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy F., Nicoll W. S., Zimmermann R., Cheetham M. E., Blatch G. L. Not all J domains are created equal: implications for the specificity of Hsp40-Hsp70 interactions. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1697–1709. doi: 10.1110/ps.051406805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L., Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins B. D., Sato K., Nakano A., Graham T. R. Introduction of Kex2 cleavage sites in fusion proteins for monitoring localization and transport in yeast secretory pathway. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K., Ghose R., Flanagan J. M., Prestegard J. H. Backbone dynamics of the N-terminal domain in E. coli DnaJ determined by 15N- and 13CO-relaxation measurements. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10567–10577. doi: 10.1021/bi990263+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O’Shea E. K. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. W., Masison D. C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp70 mutations affect [PSI+] prion propagation and cell growth differently and implicate Hsp40 and tetratricopeptide repeat cochaperones in impairment of [PSI+] Genetics. 2003;163:495–506. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G., Jones G., Wegrzyn R. D., Masison D. C. A role for cytosolic hsp70 in yeast [PSI(+)] prion propagation and [PSI(+)] as a cellular stress. Genetics. 2000;156:559–570. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen T. Clathrin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:699–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryndushkin D. S., Smirnov V. N., Ter-Avanesyan M. D., Kushnirov V. V. Increased expression of Hsp40 chaperones, transcriptional factors, and ribosomal protein Rpp0 can cure yeast prions. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:23702–23708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry S. J. Structure and energetics of an allele-specific genetic interaction between dnaJ and dnaK: correlation of nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift perturbations in the J-domain of Hsp40/DnaJ with binding affinity for the ATPase domain of Hsp70/DnaK. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4926–4936. doi: 10.1021/bi027070y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W., Zhao X., Zhang F., Eisenberg E., Greene L. E. Depletion of GAK/auxilin 2 inhibits receptor-mediated endocytosis and recruitment of both clathrin and clathrin adaptors. J. Cell. Sci. 2005;118:4311–4321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez N., Aron R., Craig E. A. Specificity of class II Hsp40 Sis1 in maintenance of yeast prion [RNQ+] Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1172–1181. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Cyr D. M. The conserved carboxyl terminus and zinc finger-like domain of the co-chaperone Ydj1 assist Hsp70 in protein folding. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5970–5978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. P., Laufen T., Paal K., McCarty J. S., Bukau B. Investigation of the interaction between DnaK and DnaJ by surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:1131–1144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville M. W., Hansen W. J., Freeman B. C., Welch W. J., Katze M. G. The molecular chaperone hsp40 regulates the activity of P58IPK, the cellular inhibitor of PKR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:97–102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. R., Prasad K., Jin S., Augustine G. J., Lafer E. M. Uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles in presynaptic terminals: roles for Hsc70 and auxilin. Neuron. 2001;32:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmyer S. L., Schmid S. L. Dominant-interfering Hsc70 mutants disrupt multiple stages of the clathrin-coated vesicle cycle in vivo. J. Cell. Biol. 2001;152:607–620. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newnam G. P., Wegrzyn R. D., Lindquist S. L., Chernoff Y. O. Antagonistic interactions between yeast chaperones Hsp104 and Hsp70 in prion curing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1325–1333. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade G. Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science. 1975;189:347–357. doi: 10.1126/science.1096303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G. S., Schekman R. Clathrin: a role in the intracellular retention of a Golgi membrane protein. Science. 1989;245:1358–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.2675311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse B. M. Coated vesicles from pig brain: purification and biochemical characterization. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;97:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse B. M. Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:1255–1259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishvaee B., Costaguta G., Yeung B. G., Ryazantsev S., Greener T., Greene L. E., Eisenberg E., McCaffery J. M., Payne G. S. A yeast DNA J protein required for uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles in vivo. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2000;2:958–963. doi: 10.1038/35046619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X., Hou W., Zhengang L., Sha B. Direct interactions between molecular chaperones heat-shock protein (Hsp) 70 and Hsp40, yeast Hsp70 Ssa1 binds the extreme C-terminal region of yeast Hsp40 Sis1. Biochem. J. 2002;361:27–34. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. S. Adaptable adaptors for coated vesicles. Trends Cell. Biol. 2004;14:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T. F., Porter K. R. Yolk protein uptake in the oocyte of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. L. J. Cell. Biol. 1964;20:313–332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. E., Schmid S. L. Enzymatic recycling of clathrin from coated vesicles. Cell. 1986;46:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele U., Alves J., Frank R., Duwel M., Kalthoff C., Ungewickell E. Molecular and functional characterization of clathrin- and AP-2-binding determinants within a disordered domain of auxilin. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25357–25368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufler C., Brinker A., Bourenkov G., Pegoraro S., Moroder L., Bartunik H., Hartl F. U., Moarefi I. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000;101:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer N., Lindquist S. Rnq1, an epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. S., Haste N. M., Ghosh G. PKR and eIF2alpha: integration of kinase dimerization, activation, and substrate docking. Cell. 2005;122:823–825. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub L. M. Common principles in clathrin-mediated sorting at the Golgi and the plasma membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1744:415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda A., Meyerholz A., Ungewickell E. Identification of the universal cofactor (auxilin 2) in clathrin coat disssociation. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 2000;79:336–342. doi: 10.1078/S0171-9335(04)70037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungewickell E., Ungewickell H., Holstein S. E. Functional interaction of the auxilin J domain with the nucleotide- and substrate-binding modules of Hsc70. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19594–19600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungewickell E., Ungewickell H., Holstein S. E., Lindner R., Prasad K., Barouch W., Martin B., Greene L. E., Eisenberg E. Role of auxilin in uncoating clathrin-coated vesicles. Nature. 1995;378:632–635. doi: 10.1038/378632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh P., Bursac D., Law Y. C., Cyr D., Lithgow T. The J-protein family: modulating protein assembly, disassembly and translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegele H., Haslbeck M., Reinstein J., Buchner J. Sti1 is a novel activator of the Ssa proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25970–25976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittung-Stafshede P., Guidry J., Horne B. E., Landry S. J. The J-domain of Hsp40 couples ATP hydrolysis to substrate capture in Hsp70. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4937–4944. doi: 10.1021/bi027333o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W., Frank C. L., Korth M. J., Sopher B. L., Novoa I., Ron D., Katze M. G. Control of PERK eIF2alpha kinase activity by the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced molecular chaperone P58IPK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002a;99:15920–15925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252341799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W., Gale M. J., Jr., Tan S. L., Katze M. G. Inactivation of the PKR protein kinase and stimulation of mRNA translation by the cellular co-chaperone P58(IPK) does not require J domain function. Biochemistry. 2002b;41:4938–4945. doi: 10.1021/bi0121499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. X., Engqvist-Goldstein A. E., Carreno S., Owen D. J., Smythe E., Drubin D. G. Multiple roles for cyclin G-associated kinase in clathrin-mediated sorting events. Traffic. 2005;6:1103–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.