Abstract

To investigate protein–protein interaction sites in the DNA mismatch repair system we developed a crosslinking/mass spectrometry technique employing a commercially available trifunctional crosslinker with a thiol-specific methanethiosulfonate group, a photoactivatable benzophenone moiety and a biotin affinity tag. The XACM approach combines photocrosslinking (X), in-solution digestion of the crosslinked mixtures, affinity purification via the biotin handle (A), chemical coding of the crosslinked products (C) followed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (M). We illustrate the feasibility of the method using a single-cysteine variant of the homodimeric DNA mismatch repair protein MutL. Moreover, we successfully applied this method to identify the photocrosslink formed between the single-cysteine MutH variant A223C, labeled with the trifunctional crosslinker in the C-terminal helix and its activator protein MutL. The identified crosslinked MutL-peptide maps to a conserved surface patch of the MutL C-terminal dimerization domain. These observations are substantiated by additional mutational and chemical crosslinking studies. Our results shed light on the potential structures of the MutL holoenzyme and the MutH–MutL–DNA complex.

INTRODUCTION

DNA mismatch repair is present in almost all organisms and required for high fidelity replication of the genome (1,2). Absence or failure of this systems leads to a mutator phenotype and in humans to predisposition to cancer (3). In Escherichia coli mismatch repair is initiated by the mismatch-binding protein MutS that after recognizing a mismatch associates with MutL in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent process (4). The ternary complex of MutS × MutL × DNA activates downstream effector proteins such as the strand discrimination endonuclease MutH. Activation of MutH leads to nicking of the DNA in the unmethylated daughter strand at a hemimethylated GATC site, which can be up to 1000 bp away from the mismatch, thereby marking the erroneous strand for MutS and MutL-dependent unwinding by DNA helicase II and excision by exonucleases (1,4). In the present study, we use MutL, a homodimeric ATPase, and one of its effector proteins, MutH. Crystal structures are available for the N-terminal [NTD, residues 1–331 (5)] and the C-terminal domain [CTD, residues 432–614 (6)] of MutL and for MutH (7,8). In vitro and in vivo studies suggest that MutL can physically interact with MutH even in the absence of MutS and a mismatch. A yeast-two hybrid analysis indicated that the CTD of MutL is sufficient for physical interaction with MutH (9), while in vitro the NTD of MutL in the presence of ATP or non-hydrolyzable analogs thereof is able to stimulate the latent endonuclease activity of MutH (5). In previous studies we mapped the protein interaction sites between the NTD of MutL and MutH via interference analysis and chemical crosslinking studies (10,11).

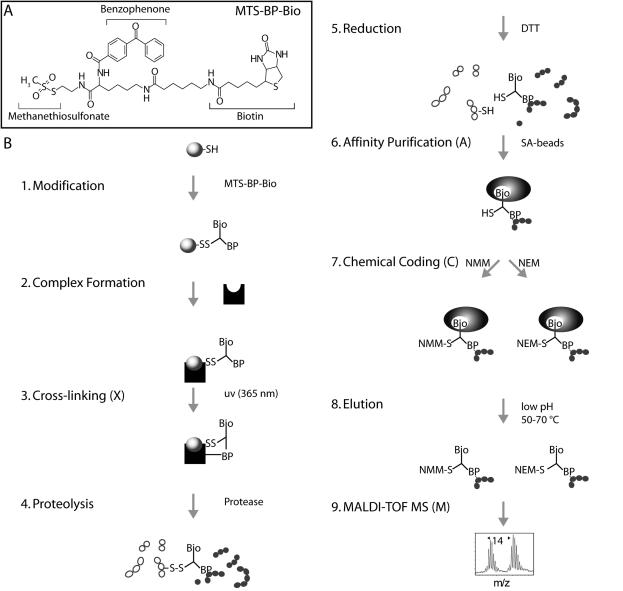

Crosslinking in combination with proteolytic digestion and mass spectrometric techniques is an especially attractive approach for studying protein–protein interactions (12–15), fold recognition (16) and the topology of protein complexes (17). Crosslinking often requires only pmol amounts of material for analysis and is capable of capturing transient complexes (13,18). Here we present a variation of the label transfer method allowing rapid identification of protein–protein interaction sites at the peptide level (14,19,20). The method relies on the commercially available trifunctional crosslinker 2-[Nα-Benzoylbenzoicamido-N6-(6-biotinamidocaproyl)-l-lysinylamido]ethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTS-BP-Bio), which includes a methanethiosulfonate (MTS) moiety for SH coupling, a biotin moiety for affinity purification using streptavidin-coated magnetic beadsand a photocrosslinking competent benzophenone moiety (Figure 1). Photocrosslinking with benzophenone has been used extensively as a photophysical probe to identify and map peptide–protein interactions (21,22). Our modular method named XACM combines well-established protocols for (X) photocrosslinking (22), (A) affinity purification of biotinylated peptides by streptavidin coated magnetic beads (23) and (C) coding technologies followed by (M) mass spectrometry identification (24). Chemical coding generates modified peptide species with similar chemical properties but masses separated by a characteristic mass increment thereby facilitating identification of the coded peptides in mass spectra. The overall strategy of the XACM method and the structure of the MTS-BP-Bio reagent are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of XACM (X, Crosslinking; A, affinity purification; C, chemical coding and M, mass spectrometry). (A) Structure of the trifunctional crosslinker MTS-BP-Bio. (B) Schematic representation of the XACM method used to identify protein interaction sites on the peptide level by photocrosslinking/affinity purification/chemical coding/MALDI-TOF MS. (1) A protein is modified at thiol groups with MTS-BP-Bio thereby forming a disulfide bond. (2) The interaction partner is added to allow complex formation (not necessary in case of obligate protein complexes). (3) Photocrosslinking of the benzophenone moiety to the interaction partner is initiated by irradiation at 365 nm. (4) Proteins and crosslinked complexes are then digested in-solution with proteases. (5) The crosslinked products are cleaved at their disulfide linkage thereby transferring the biotin group to the peptide of the interaction partner. (6) The peptides bearing the biotin moiety of the crosslinker are captured on streptavidin coated magnetic beads [14]. (7) The sample is split and the biotinylated peptides are chemically coded at their free thiol group of the crosslinker with N-methylmaleimide (NMM) or N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to give two products with a mass difference of 14 atomic mass units. (8) The coded peptides are combined and eluted. (9) Coded peptides are identified by MALDI-TOF MS by the characteristic doublets separated by 14 a.m.u.

First, we demonstrate the feasibility of the XACM method by identifying the crosslinked peptide using a single-cysteine variant of the homodimeric MutL protein. Second, we successfully applied the method to investigate the photocrosslink between the single-cysteine MutH variant A223C and its activator protein MutL. Using the XACM technique described here, we were able to identify the crosslinked product between a MutH peptide comprising residue 223 and a MutL-peptide (residues 525–541) of the CTD. These data are in agreement with the yeast-two hybrid analysis, which showed the interaction between MutH and the CTD of MutL (9). By combining data from this and previous studies, we begin to shed light on the structure of the MutH–MutL complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids and reagents

E.coli K12 strain TX2652 (CC106 mutL::Ω4 (BsaAI; Kanr), TX2928 (CC106 but mutH471::tn5;Kanr) (25) and the pET-15b (Novagen) derived plasmids pTX412 (His6-MutS) and pTX418 (His6-MutL) containing the genes for hexahistidine-tagged MutS and MutL proteins, respectively, were kindly provided by Dr M. Winkler (25). Plasmid pMQ402 (His6-MutH), a pBAD18 derivative, containing a gene for a MutH protein with a hexahistidine tag was a kind gift of Dr M. Marinus (26). Plasmid pMQ402/Cys-free coding for the cysteine-free variants of MutH (MutHCF) and plasmid pTX418/Cys-free coding for the cysteine-free variant of MutL (MutLCF) have been described before (10,11). The E.coli strains HMS174 (λDE3) from Novagen and XL1-blue MRF′ from Stratagene were used for protein expression. Bacteriological media have been described previously (11).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Single-cysteine variants of MutH at codon 223 (SC-MutHA223C, numbering referring to the E.coli wild-type sequence) and MutL at codon 282 (SC-MutLA282C) were generated using plasmids pMQ402/Cys-free and pTX418/Cys-free, respectively, by a modified Quikchange protocol (Stratagene) essentially as described elsewhere (10,11,27). To generate SC-MutHA223C the oligodeoxynucleotide CAG AAA ATG ACG aca CAG TAG TGC ACT G was used (lower case and underlined letters indicate the exchanged nucleotides and the codon, respectively). For SC-MutLA282C, the oligodeoxynucleotide CAA ACT GGG Gtg CGA TCA GCA AC was used. Variants MutLR531A and MutLR531E were generated using the plasmid pTX418 and the oligodeoxynucleotides GTA AAT TTT GTT GGg cTA gcG GTA AAG GCA CT and GTA AAT TTT GTT Gtt cTA gaG GTA AAG GCA CT, respectively. E.coli XL1-blue MRF' cells were transformed with the full-length PCR products. Marker positive clones were inoculated and grown overnight in Luria–Bertani (LB) containing ampicillin. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and verified by automated sequencing.

Complementation mutator assay

Cells lacking a functional chromosomal mutL gene show a mutator phenotype, which can be analyzed by the frequency of rifampicin resistant clones (26). Single colonies of mutL-deficient TX2652 or mutH-deficient TX2928 cells transformed with a vector control (e.g. pET-15b) or plasmids coding for the indicated variant MutL or MutH proteins, respectively, were cultured overnight at 37°C in 3 ml LB media containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin. Aliquots of 50 µl from the undiluted cultures were plated on LB agar containing 25 µg/ml ampicillin and 100 µg/ml rifampicin. Colonies were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C.

Protein expression and purification

Recombinant His6-tagged MutH, MutL and MutS proteins were expressed and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography and gel filtration chromatography essentially as described before (11). MutH proteins were stored at −20°C in 10 mM HEPES–KOH, 500 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 50% glycerol, pH 7.9. MutL and MutS proteins were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C in 10 mM HEPES–KOH, 200 mM KCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.9. Protein concentrations were determined using theoretical extinction coefficients (28).

MutH endonuclease assay

MutH endonuclease activity was assayed on a heteroduplex DNA substrate (484 bp) containing a G/T or A/C mismatch at position 385 (numbering with respect to the top strand) and a single unmethylated d(GATC) site at position 210 as described previously (11). Briefly, 25 nM of the heteroduplex DNA was incubated at 37°C with 500 nM MutH, 2 µM MutL and 1 µM MutS in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP and 125 mM KCl. At suitable time points, 10 µl aliquots were removed and the reaction stopped by addition of 3 µl of 250 mM EDTA, 25% (w/v) sucrose, 1.2% (w/v) SDS and 0.1% (w/v) bromophenol blue, pH 8.0, to 10 µl aliquots. Substrates and products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and analyzed using a gel imaging and analysis system (BioDocAnalyze; Biometra). Initial rates were determined from the linear portion of the time course.

Photocrosslinking

Protein (50–200 pmol) containing a thiol group in 50 µl labeling buffer (125 mM KCl and 10 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.5) was incubated at 25°C with a 1- to 10-fold molar excess of MTS-BP-Bio (Toronto Research Chemicals; dissolved in DMSO at 36 mM) in a reaction up to several minutes (29). Excess reagent was removed using Protein Desalting Spin Columns (Pierce) equilibrated with labeling buffer. Alternatively, proteins were labeled with 4-(N-maleimido)benzophenone (MBP, Sigma) essentially as described before (11). After allowing complex formation with an interaction partner (or directly after modification of an obligate protein complex) in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM non-hydrolyzable ATP analog adenosine 5′-(β-γ-imido)triphosphate, photocrosslinking via the benzophenone moiety to neighboring amino acid residues was initiated by UV irradiation (365 nm) with a handheld UV-lamp of 2 × 6 watt in a distance of 5 cm for 5–15 min on ice. Crosslinking yield was assessed after separating the reaction mixture by SDS–PAGE, Coomassie staining and analysis using a gel imaging and analysis system (BioDocAnalyze; Biometra) (Figure 2B).

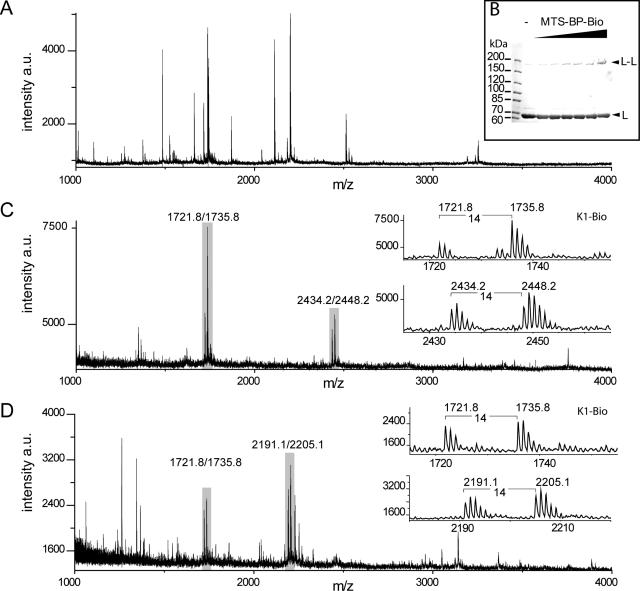

Figure 2.

Analysis of photocrosslinking SC-MutLA282C by SDS–PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS. (A) (Partial positive ion) MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of tryptic peptides (corresponding to 25 pmol input of SC-MutLA282C) before affinity purification. (B) SDS–PAGE analysis (6% gels) of crosslink reactions of homodimeric SC-MutLA282C (5 µM) with increasing molar excess MTS-BP-Bio ranging from 1- to 20-fold. (C) MALDI-TOF spectrum after affinity purification and chemical coding with NMM and NEM. The control peptide K1-Bio (2.5 pmol) was added prior to affinity purification (Table 1). (D) same as (C) but the proteolysis was performed with trypsin and Glu-C. Peaks doublets labeled of the internal biotinylated control peptide K1-Bio coded with NMM and NEM (m/z 1721.8/1735.8), and crosslinked peptides are labeled and shown in the insets (Table 1). All ions are protonated molecules and the m/z values refer to those of monoisotopic mass. Intensities are given in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Digestion of the photocrosslinked protein complexes

Digest of the photocrosslinking reaction mixture (50 µl) was performed in solution for 12 h at 37°C using either 1.25 µg trypsin (High-Sequencing-Grade™; Roche Diagnostics) or a mixture of 1.25 µg trypsin and 2 µg endoproteinase Glu-C (HPLC pure; Sigma). In some cases, in-gel digestions of gel slices containing the crosslinked products were carried out essentially as described elsewhere (11) with the exception that the samples were modified on thiol groups with either N-methylmaleimide or N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma). Proteases were inactivated by addition of freshly prepared phenylmethlysulfonyl fluoride to a final concentration of 5 mM.

Affinity purification and chemical coding

Prior to affinity purification 35 µl of water and 10 µl of 10× binding buffer (500 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 and 10 mM DTT) were added to 55 µl of the in-solution protease digest mixture. For affinity purification of biotinylated crosslinked peptides, a modified protocol of Girault et al. (23) using streptavidin-coated (SA) magnetic beads (M-280, Dynal) was used. After incubation and immobilization of 400 µg SA magnetic beads with a magnetic concentrator (Dynal), the supernatant was removed and the beads were washed twice with 100 µl cleaning buffer (500 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM DTT and 1 mg/ml BSA) followed by 100 µl binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 and 1 mM DTT). Next the beads were mixed with 100 µl of the in-solution protease digests (corresponding to 200 pmol protein) spiked with 2 µl biotinylated internal control peptide K1-Bio (20 pmol; Table 1) and incubated for 60 min at 25°C with shaking. The supernatant was removed and the beads were washed four times with 100 µl washing buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4 and 0.01% (v/v) N-octylglucoside], four times with 100 µl of 1 mM DTT and finally three times with 100 µl water. In the final wash step, the bead solution was split into two equal aliquots prior to removing the supernatant. Thiol groups were chemically coded by adding 100 µl of either freshly prepared 10 mM N-methylmaleimide or N-ethylmaleimide in 100 mM NH4HCO3 and incubating for 60 min at 25°C in the dark with shaking. After removal of the supernatant, beads were resuspended in 50 µl water, the samples combined and washed again twice with 100 µl water. Peptides were eluted with 50 µl of 0.1% (v/v) TFA, 40% (v/v) ethanol by incubation for 5–10 min at 60°C (30) and the supernatant containing the eluted crosslinked peptides was recovered. The beads were treated with 50 µl of 100% acetonitrile for 60 min at 25°C and this supernatant recovered as well. Eluates were dried in a Speedvac and stored at −20°C for further analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of control peptides and crosslinked peptides

| Peptide/proteina | Sequence and monoisotopic mass | Proteases | Modificationb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Expected | ||||

| K1-Bio | RDCKSTYRKD-Biotina C67H111N21O21S2 [M+H]+ = 1610.78 | None | NMM C5H5N1O2 111.03 | 1721.83 ± 0.02 | 1721.81 |

| None | NEM C6H7N1O2 125.05 | 1735.85 ± 0.02 | 1735.83 | ||

| MutL homocomplex | |||||

| SC-MutLA282C | 267LINHAIRQAYEDK279 C69H111N21O21 [M+H]+ = 1570.83 | Trypsin | NMM-S-BP-Bio C43H57N7O8S2 863.37 | 2434.17 ± 0.03 | 2434.20 |

| Trypsin | NEM-S-BP-Bio C44H59N7O8S2 877.39 | 2448.18 ± 0.04 | 2448.22 | ||

| 267LINHAIRQAYE277 C59H94N18O17 [M+H]+ = 1327.71 | Trypsin/Glu-C | NMM-S-BP-Bio C43H57N7O8S2 863.37 | 2191.10 ± 0.02 | 2191.08 | |

| Trypsin/Glu-C | NEM-S-BP-Bio C44H59N7O8S2 877.39 | 2205.13 ± 0.03 | 2205.10 | ||

| MutH–MutL heterocomplex | |||||

| SC-MutHA223C (XAMc) | 216NFTSALLCR224 C44H73N13O13S1 [M+H]+ = 1024.52 | Trypsin/Glu-C | S-BP-Bio C38H50N6O6S2 750.32 | 1774.78 ± 0.07 | 1774.85 |

| MutLCF (XAMc) | 525AVPLPLRQQNLQILIPE541 C89H152N24O24 [M+H]+ = 1942.15 | Trypsin/Glu-C | 216NFTSALLCR 224 + S-BP-Bio C82H123N19O19S3 1773.84 | 3715.62 ± 0.4 | 3715.99 |

| MutLCF (XACMd) | 525AVPLPLRQQNLQILIPE541 C89H152N24O24 [M+H]+ = 1942.15 | Trypsin/Glu-C | NMM-S-BP-Bio C43H57N7O8S2 863.37 | 2805.40 ± 0.12 | 2805.52 |

| Trypsin/Glu-C | NEM-S-BP-Bio C44H59N7O8S2 877.39 | 2819.40 ± 0.14 | 2819.54 | ||

aBiotinylaminohexanoic acid.

bSee Figure 1.

cAnalysis without DTT cleavage and chemical coding.

dAnalysis after DTT cleavage and chemical coding.

Mass spectrometry

Crosslinked peptides were analyzed by MALDI-MS and candidate masses were identified by characteristic doublet peaks. Peptides were dissolved in 4 µl of 0.1% (v/v) TFA, 40% (v/v) ethanol and 0.5 µl of this mixture was combined with an equal volume of 10 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxy benzoic acid in 0.1% (w/v) TFA, 40% (v/v) ethanol, applied on the MALDI target and allowed to crystallize using the dried-droplet method. Mass spectra (averaged 100–200 laser shots) were recorded with a home-built two-stage reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Advanced Laser Desorption Ionisation Mass Analyser II, ALADIM II) (31) in the reflector mode. The instrument is equipped with a nitrogen laser (λ = 337 nm, pulse duration = 3 ns, energy = 300 µJ; VSL 337 NDS Laser; Laser Science Inc. Cambridge, MA, USA) and externally calibrated with 1 µl of a peptide mixture of substance P, mellitin and bovine insulin. After assignment of monoisotopic peaks, data were analyzed with GPMAW 6.2 (Lighthouse data).

Thiol–thiol crosslinking

Chemical crosslinking of SC-MutHA223C to the indicated MutL variants was performed essentially as described previously (11). Briefly, proteins were incubated at 5 µM each in 20 µl labeling buffer containing 1 mM adenosine 5′-(β-γ-imido)triphosphate for 10 min on ice. Crosslinking was initiated at 25°C by adding 1 µl of the homobifunctional reagent 1,8-bismaleimidotetraethyleneglycol (BM[PEO]4, Pierce) to a final concentration of 100 µM. The reactions were quenched after 30 s by adding DTT to a final concentration of 5 mM. Crosslinking reaction mixture were subjected to SDS–PAGE and analyzed as described above. For preparative crosslinking 29 µM SC-MutHA223C and 29 µM SC-MutL480C were incubated in 700 µl buffer containing 10 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl and 5 mM MgCl2 with 145 µM homobifunctional crosslinker 3,6,9-trioxaundecane-1,11diylbismethanethiosulfonate (MTS-11-O3-MTS, Toronto Research Chemicals) for 5 min at 25°C. The reaction was quenched by adding N-ethylmaleimide to a final concentration of 5 mM. The crosslink reaction mixture was subjected to gel filtration on a Superdex 75 column equilibrated 10 M mM HEPES–KOH, pH 8.0, 500 mM KCl and 1 mM EDTA at 1 ml/min flow rate. Fractions containing the crosslinked complex eluting between 8 and 8.9 min were pooled, concentrated with amicon ultra-4 (cutoff 100 000; Millipore), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until further analysis.

Sequence alignment and calculation of evolutionary rates

The amino acid sequences of E.coli MutL and MutH were used as query to search the non-redundant database (nr) using PSI-BLAST (32). Sequences from γ-proteobacteria containing genes for both MutL and MutH homologs were collected. Additional databases from prokaryotic genomes available via the Genomes On Line Database (33) were also searched. The initial multiple sequence alignment was generated using PCMA (34) and refined based on the results of fold-recognition analysis reported by the GeneSilico MetaServer (35). The phylogenetic tree was calculated using the Maximum Likelihood method implemented in PHYML (36) based on an alignment from which columns representing diverged regions were removed. The alignment and phylogenetic tree were submitted to the Consurf 3.0 server (37) to generate normalized evolutionary rates for each position of the alignment (low rates of divergence correspond to high sequence conservation).

RESULTS

During DNA mismatch repair the strand discrimination endonuclease MutH is activated by transient physical interaction with MutL. In order to characterize this interaction in more detail we developed a novel method for facilitated identification of photocrosslinking products using mass spectrometry. The results from this analysis were corroborated by mutational analysis and chemical crosslinking. Moreover, we used the identified interaction site to create and purify an active covalently crosslinked complex of MutH and MutL.

Identification of a photocrosslinked product in the homodimeric MutL single-cysteine variant SC-MutLA282C using the XACM technique

The applicability of the XACM technique is shown by the identification of a crosslink in the homodimeric SC-MutLA282C. In the structure of the NTD of MutL [pdb code 1b63, (5)] Ala282 is <20 Å from the other subunit, a distance, which is compatible with the range of the MTS-BP-Bio crossslinker. Modification of SC-MutLA282C with MTS-BP-Bio followed by photocrosslinking yields a new band on SDS–PAGE (Figure 2B) that is also observed using the non-cleavable photocrosslink reagent MBP. Typical crosslinking yields were estimated to be 10–20% of the input protein. However, after standard in-gel tryptic procedures (38), we were not able to identify any crosslinked species by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 2A). In contrast, using the XACM procedure (Figure 1) we readily identified a tryptic peptide fragment (267LINHAIRQAYEDK279) modified with a chemically coded crosslinker (Figure 2C and Table 1). This modified fragment contains one missed tryptic cleavage site, possibly the result of photocrosslinking at or near Arg273 such that this site is no longer recognized by trypsin. Notably, we could not detect this fragment in the complex mixture prior to affinity purification either from the in-solution or the in-gel digests (data not shown). However, after affinity purification and chemical coding the modified peptide was often the major signal in the mass spectrum and could be distinguished from other signals by the presence of signal doublets separated by 14 atomic mass units. A shortened form of this peptide (267LINHAIRQAYE277) was found in the combined trypsin/Glu-C digest (Figure 2D). Using the MutL NTD structure (5), we measured the distance of the identified peptide to residue 282 in either the same subunit (intramolecular) or the sister subunit (intermolecular). The distances in both cases are <20 Å and thus compatible with the size of the MTS-BP-Bio crosslinker implying the method is in principle suitable for identifying crosslinked peptides from a complex mixture without gel electrophoretic or chromatographic separation steps. However, in the absence of additional data we cannot assess whether the detected crosslink is intra- or intermolecular.

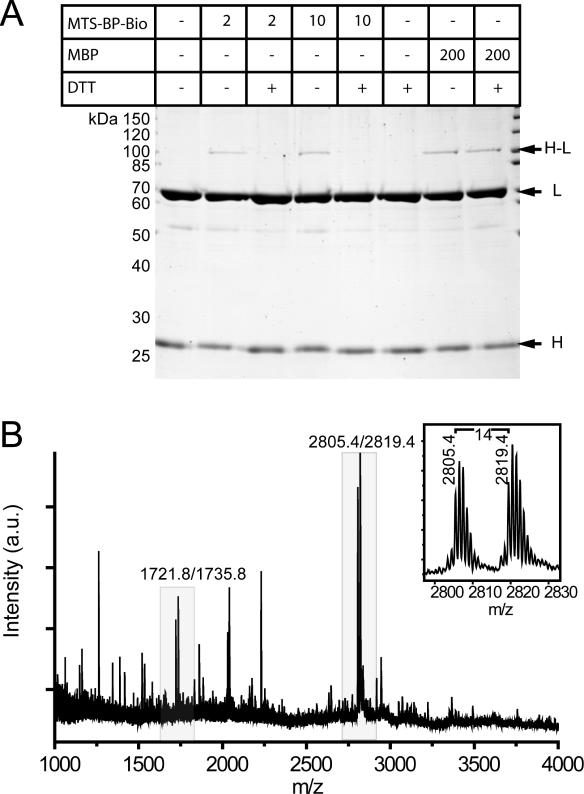

Identification of the photocrosslink product between SC-MutHA223C and MutLCF

Based on the structural analysis of three different structures of MutH in the absence of DNA and a mutational analysis of MutH, the C-terminal helix (helix F, residues 215–224) of MutH had been suspected to be part of the MutL interaction site (8,26). We generated a single-cysteine variant of MutH at position 223 (SC-MutHA223C) in order to probe for physical interaction with MutL using a photocrosslinking approach. SC-MutHA223C modified with either MTS-BP-Bio or MBP can be photocrosslinked to MutLCF, suggesting that helix F of MutH is part or close to the MutL interaction site (Figure 3A). However, we were not able to identify a crosslinked peptide after in-gel protease digestion and mass spectrometry (data not shown) using either MBP of MTS-BP-Bio as a crosslinker. We therefore wanted to determine if the XACM technique would allow us to identify the crosslinked peptide. The mixture from the photocrosslinking reaction with MTS-BP-Bio modified SC-MutHA223C was subjected to the XACM procedure making use of trypsin and endoproteinase Glu-C. By searching for mass doublets separated by the characteristic 14 atomic mass units introduced after chemical coding, we were able to identify a modified peptide fragment of MutL (525AVPLPLRQQNLQILIPE541, Table 1 and Figure 3B) that also contains a missed tryptic cleavage site at Arg531. In addition, we analyzed the crosslinking reaction mixture after proteolysis and affinity purification but without DTT cleavage of the crosslinked peptide and chemical coding using MALDI-TOF MS. A major peak in the mass spectrum could be assigned to a cysteine-containing peptide of MutH (216NFTSALLCR224) modified with the MTS-BP-Bio crosslinker (Table 1). We were also able to assign a peak of lower intensity to a crosslinked species comprising the MTS-BP-Bio modified peptide from MutH (216NFTSALLCR224) and the peptide from MutL (525AVPLPLRQQNLQILIPE541) that we had identified using the XACM procedure. However, in contrast to the complex analysis of the uncleaved crosslinked peptides the identification of the chemical coded peptide was much simpler. The identified peptide of MutL is part of the CTD responsible for dimerization (6) that has been shown by yeast-two hybrid analysis to contain a protein interaction site for MutH (9). Further, the identified peptide contains a highly conserved seq uence motif in MutL (530LRQQNLQ536) that we predicted previously based on bioinformatic analysis to be part of a protein-interaction patch (39).

Figure 3.

Analysis of photocrosslinking SC-MutHA223C to its activator protein MutLCF by SDS–PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS. (A) SDS–PAGE analysis of crosslink reactions of the heterocomplex of SC-MutHA223C (5 µM) modified with either 5-fold molar excess of the non-cleavable photocrosslinker MBP in comparison with MTS-BP-Bio. After complex formation with MutLCF and irradiation, (365 nm 10 min) new bands are observed (H-L). (B) Partial positive ion MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of peptides obtained by trypsin/Glu-C digestion of the MTS-BP-Bio crosslinking reaction mixture (corresponding to 25 pmol input of MutL) after affinity purification and chemical coding with NMM and NEM. The control peptide K1-Bio (2.5 pmol) was added prior to affinity purification (Table 1). All ions are protonated molecules and the m/z values refer to those of monoisotopic mass. Intensities are given in arbitrary units (a.u.).

In vivo and in vitro activities of variants MutLR531A and MutLR531E

As noted above the identified MutL crosslinked peptide fragment (525AVPLPLRQQNLQILIPE541) contains a missed tryptic cleavage site at Arg531. Since arginine is known to have a high intrinsic reactivity towards photoalkylation with benzophenone (40), we generated the two variants MutLR531A and MutLR531E to remove the potential attachment site for the benzophenone moiety. Given that Arg531 is part of a surface patch that is highly conserved in MutL proteins from bacteria also containing a gene for MutH (39), it is possible that exchanging this conserved residue affects the function of the protein, e.g. by interrupting the MutL interaction with MutH or DNA. We therefore tested both variants for their activity in vivo and in vitro. Indeed, both plasmid-encoded MutL variants were less efficient in complementing a mutL-mutator phenotype in vivo (Table 2). We purified both variants and tested their ability to activate the MutH endonuclease in a mismatch and MutS-dependent manner. Since MutLR531A and MutLR531E are still able to activate the MutH endonuclease in vitro (Table 2), we concluded that Arg531 is important for MutL function in vivo but not essential for MutH activation (at least under the experimental conditions used in vitro). This implies that both MutL variants can interact functionally with MutH and are therefore appropriate for probing photocrosslinking with SC-MutHA223C labeled with benzophenone.

Table 2.

Activity of MutL and MutH variants

| Variant | In vivo | In vitro | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediana | Rangeb | Activityc (%) | SE | |

| MutL | ||||

| Vector (mutL null) | 1023 | 806–1891 | N/A | N/A |

| MutLwt | 3 | 0–69 | 100 | 10 |

| MutLCF | 13 | 6–66 | 98 | 7 |

| SC-MutLA282C | 1.5 | 0–10 | 72 | 12 |

| MutLR531E | 120 | 62–280 | 115 | 5 |

| MutLR531A | 38 | 0–165 | 91 | 10 |

| MutH | ||||

| vector (mutH null) | 1500 | 79 to >5000 | N/A | N/A |

| MutHwt | 3.5 | 0–35 | 100 | 10 |

| MutHCF | 1 | 0–16 | 121 | 9 |

| SC-MutHA223C | 20.5 | 10–57 | 81 | 10 |

aFor in vivo activity the rpo mutation assay was used (for details see Materials and Methods). Median number of rifampicin resistant clones which arise by spontaneous mutation. Results obtained from 10 independent cultures. For mutations frequencies of MutLwt, MutLR531A and MutLR531E see Supplementary Table I.

bMinimum and maximum number of rifampicin resistant clones.

cMutL activity was measured by mismatch and MutS-dependent activation of MutH to cleave a linear 484 bp heteroduplex substrate containing a single d(GATC) site as described in Materials and Methods. Errors shown are ±1 SD. For the dependence of the mismatch-provoked MutH activation on the concentration of MutLwt, MutLR531A and MutLR531E see Supplementary Figure 1.

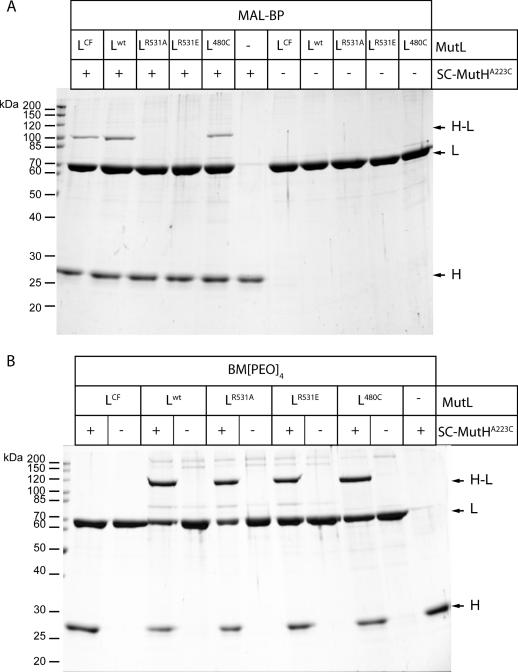

MutLR531E and MutLR531A are not photocrosslinked to the SC-MutHA223C labeled with MBP

We tested both MutL variants, R531A and R531E, for their ability to form a photocrosslink with the SC-MutHA223C labeled with MBP. As shown in Figure 4A, wild-type MutL, cysteine-free variant MutLCF and SC-MutL480C (39) are able to form a photocrosslink with SC-MutHA223C. In contrast, we did not observe any photocrosslink between SC-MutHA223C and either MutLR531A or MutLR531E in which Arg531 is no longer present. This indicates that either the acceptor amino acid for the benzophenone moiety is no longer available or that the interaction between MutH and the CTD of MutL has been impaired upon substitution of Arg531 for alanine or glutamic acid. Inspection of the MutL-CTD structure revealed the presence of a solvent exposed cysteine residue (Cys480) at a distance of 10 Å to Arg531. Since Cys480 is the only solvent exposed cysteine residue in the CTD of MutL, we used the long-range homobifunctional crosslinker BM[PEO]4 to test whether Cys223 of SC-MutHA223C is close enough to form a crosslink. The results demonstrate that all MutL variants except MutLCF can be crosslinked to SC-MutHA223C using BM[PEO]4 (Figure 4B). This suggests that substituting Arg531 for alanine or glutamic acid does not abolish the physical interaction of the MutL CTD with MutH. In summary, since the variants MutLR531A and MutLR531E are still able to interact with MutH both physically and functionally, we conclude that Arg531 is a likely candidate to be the acceptor of the benzophenone moiety in the photocrosslinking reaction with SC-MutHA223C. The absence of a photocrosslink with MutLR531A and MutLR531E would thus be due to the absence of a suitable acceptor amino acid. However, additional experiments (e.g. sequencing of the photocrosslinked peptide by MS/MS) are needed to identify unequivocally the crosslink position at the amino acid level.

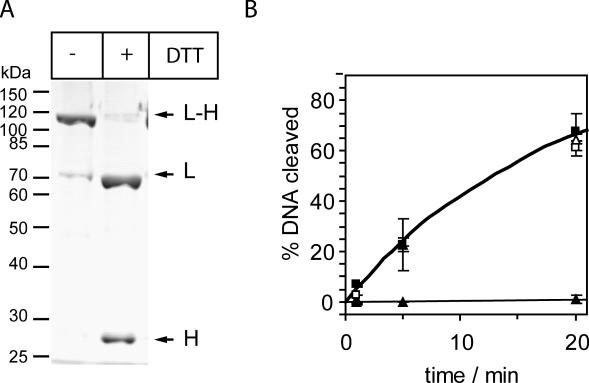

Figure 4.

Analysis of crosslinking SC-MutHA223C to its activator protein MutL by SDS–PAGE. (A) Photocrosslink reactions of the heterocomplex formed by SC-MutHA223C modified with MBP and the indicated MutL variants. After complex formation with MutL and UV-irradiation new bands are observed (H–L). Note that both MutLR531A and MutLR531E fail to form a photocrosslink with SC-MutHA223C. (B) Chemical crosslinking of SC-MutHA223C to the indicated MutL variants with the cysteine specific homobifunctional crosslinker BM[PEO]4. All MutL variants but MutLCF are able to form a chemical crosslink with SC-MutHA223C.

Crosslinking MutH to MutL abolish MutS requirement to activate the MutH endonuclease

In vitro MutL is sufficient to activate the MutH endonuclease in a mismatch and MutS-independent manner (5,9). This activation is observed at low ionic strength (<100 mM). However, at physiological relevant ionic strength [100–160 mM (41)] optimal for DNA mismatch repair, activation of MutH is mismatch and MutS dependent (42). Here, we investigated the crosslinked complex between SC-MutHA223C and SC-MutL480C for its MutH endonuclease activity in the absence and presence of MutS. To this end, we employed a chemical crosslinker (MTS-11-O3-MTS) that can be removed upon reduction with DTT. The crosslinked complex was purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Figure 5A). Upon treatment with DTT, the crosslinked complex could be cleaved. MutH in the crosslinked and uncrosslinked (DTT-treated) form was then tested for its ability to cleave a 484 bp long heteroduplex DNA substrate containing a single d(GATC) site at physiological ionic strength (125 mM KCl) in the presence and absence of MutS (Figure 5B). In the presence of MutS, we did not observe any difference in activity between the crosslinked and uncrosslinked MutH-MutL, indicating that the crosslink is not impairing the function of either MutH or MutL during the process of mismatch- and MutS-dependent activation of MutH. In the absence of MutS the uncrosslinked (DTT-treated) complex was not able to cleave DNA in buffers containing 125 mM KCl (Figure 5B); however, stimulation was observed at lower ionic strength (50 mM KCl; data not shown). In contrast to this, the crosslinked complex of MutH and MutL retained the ability to cleave DNA even at concentration of 125 mM KCl (Figure 5B). Taken together these results suggest that crosslinking of the C-terminal helix of MutH via position 223 to Cys480 of the CTD of MutL did not disturb the function of the MutL–MutH complex but rather render the complex independent from MutS.

Figure 5.

Chemical crosslinking SC-MutHA223C to SC-MutL480C abolishes MutS requirement for MutH activation. (A) SDS–PAGE analysis of HPLC-purified complex SC-MutHA223C with SC-MutL480C crosslinked with the cleavable reagent MTS-11-O3-MTS (for details see Materials and Methods) before and after treatment with 5 mM DTT. The amount of uncrosslinked SC-MutHA223C co-purifying with the complex was judged to be <5% of the crosslinked MutH. (B) MutH DNA cleavage promoted by MutL and MutS was assayed as described in Materials and Methods using a 484 bp heteroduplex DNA (25 nM). The complex of SC-MutHA223C/SC-MutL480C (1 µM) crosslinked (−DTT, open symbols) or uncrosslinked (+DTT, closed symbols) was assayed in the absence (triangles) or presence (squares) of 1 µM MutS. Note that only in the crosslinked complex MutH is able to cleave DNA even in the absence of MutS.

DISCUSSION

A key step in E.coli DNA mismatch repair is coupling mismatch recognition by MutS and strand discrimination by MutH (1). Various models have been proposed and most of them involve the formation of a complex comprising MutS, MutL and MutH (43). However, our knowledge regarding the structure of the binary or ternary protein–protein complexes is limited. Crosslinking has long been used to identify interacting proteins and to map protein interaction sites (17). However, detection of the crosslinked peptide from the reaction mixture is often like ‘finding a needle in the haystack’ even when employing advanced mass spectrometry techniques. Hence, enrichment of the crosslinked product is often necessary for successful identification and several methods have been developed in recent years (44). Here, we demonstrate that crosslink identification in a larger protein complex can be simplified by combining crosslinking, affinity purification and chemical coding technologies prior to mass spectrometry (XACM).

The modularity of the XACM method offers several possibilities for modifications. By thiolation of amino groups of lysine (e.g. 2-iminothiolane or N-succinimidyl-S-acetylthioacetate) MTS-BP-Bio can also be applied to proteins devoid of cysteine residues. In case the proteins contain more than one cysteine or lysine residue, however, care must be taken to limit the number of modifications in order to preserve a functional protein. Moreover, the complexity of the reaction mixture will increase. The advantage of the biotinylated photocrosslinker will possibly overcome these shortcomings allowing affinity purification/enrichment of the crosslinked species from complex mixtures. Reagents like the amino specific Sulfo-SBED may be used instead of MTS-BP-Bio without changing the remainder of the protocol (45). In addition, prior to proteolytic digestions the proteins may be purified by any method available to separate the covalently crosslinked complex (e.g. by size exclusion chromatography), although any additional chromatographic or gel electrophoretic steps might result in sample loss. The purity and the small number of derivatized peptides offer the possibility to analyze these crosslinked products by nano ESI-MS. Finally, any reagents available for thiol modification, such as described for the ICAT (46), ECAT (47) or VICAT (48) methods, may be used instead of chemical coding during affinity purification.

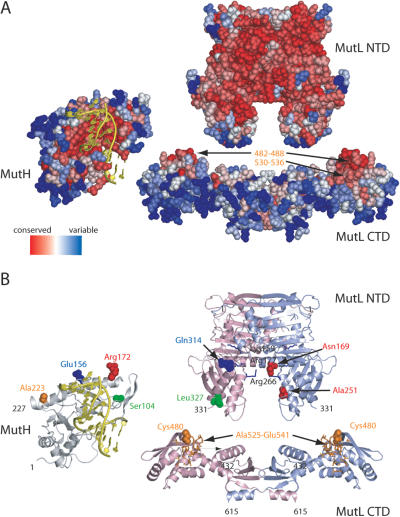

We successfully applied the XACM method presented here to identify an as yet unknown protein–protein interaction site at the peptide level between the CTD of MutL and a single-cysteine variant of its effector protein MutH (Figure 3). This finding is corroborated by mutational and additional crosslinking studies (Figure 4). Figure 6 summarizes our present crosslinking data on the MutL–MutH complex. However, modeling this complex, e.g. by docking, is a complicated task because a structure of the MutL holoenzyme is not available. Structures are known only for the NTD (residues 1–331) and the CTD (residues 432–614). Neither the structure of the 100 amino acid non-conserved linker (residues 332–431) nor the orientation of the NTD relative to the CTD are known. Recently, we proposed that based on sequence-conservation analysis the conserved site of the CTD faces the NTD (39). This proposition is corroborated by our crosslinking results. We have shown previously that the protein interaction site for MutH in the NTD is outlined by residues Asn169 and Ala251 of one subunit of the homodimer and residues Gln314 and Leu327 of the other subunit (10,11). As shown in Figure 6, the crosslink positions in MutH and MutL identified using chemical and photochemical crosslinkers are only compatible with a model for the MutL holoenzyme in which the conserved sites (residues 482–488 and 530–536) are pointing towards the NTD, assuming that both domains share a common dyad axis. So far, we have not been able to observe any crosslinking between the NTD and CTD and it remains to be shown whether these domains separated in sequence by a 100 amino acid long non-conserved linker are adjacent to one another. It is known from other studies that the linker length is essential for in vivo function of MutL (6).

Figure 6.

Residue sequence conservation and crosslinking results mapped onto the structures of MutH (pdb code 2azo chain B), MutL NTD (pdb code 1b63) and MutL CTD [pdb code 1x9z, (39)]. DNA taken from the structure of the co-crystal from Haemophilus influenzae MutH with specific DNA (pdb code 2aoq) has been superimposed on the structure of E.coli MutH. MutH is shown relative to MutL NTD in an ‘open book’ view based on docking results (11). The NTD and CTD of MutL are aligned arbitrarily to share a common dyad axis. (A) Residue sequence conservation using only protein sequences from bacteria with a gene for both MutH and MutL was obtained using the CONSURF server (56). Conserved residues predicted to be a potential protein interaction site are labeled in yellow (39). (B) Cartoon diagrams of MutH and MutL. The two subunits of the MutL homodimer are colored in light green and blue, respectively. Residues involved in DNA binding (Lys159, Arg177 and Arg266) are shown as sticks colored in blue (49). Positions of cysteine residues in single-cysteine variants of MutH and MutL are indicated as solid spheres. Positions in MutH and MutL that can be crosslink with homobifunctional reagents [Ref. (11) and this study] are shown in the same color. The MutL-peptide crosslinked to cysteine-223 in SC-MutHA223C modified with MTS-BP-Bio and identified using XACM is shown as sticks colored in orange. Note that the conserved site of the CTD should face towards NTD to match all the restraints from the crosslinking experiments (for details see text).

Both MutH and MutL are DNA-binding proteins and DNA binding of MutL has been shown to be important for mismatch repair and DNA helicase II activation (5,6,49,50). Under physiological relevant salt concentration, the ability of MutL to bind to double-stranded DNA is strongly impaired (51). MutL has a much higher affinity to single-stranded DNA or DNA with a 3′-overhang compared to double-stranded DNA (50). DNA binding in the mutant MutLR266E was impaired in DNA binding and stimulation of DNA helicase II (6,50). In contrast to this, activation of MutH by MutL is not or only slightly affected upon exchanging residues in MutL involved in DNA binding (49,50). Hence, it remains to be shown whether MutL is in direct contact to the DNA in a ternary complex comprising MutL, MutH and DNA. Moreover, it is not known whether MutH contacts both the NTD and CTD domains of MutL prior to or after DNA binding by MutH. Since we could demonstrate that crosslinking MutH to the CTD domain of MutL does not affect its ability to cleave DNA (Figure 5B), we conclude that MutH need not to dissociate from the CTD of MutL in order to bind and cleave DNA. Crosslinking both proteins generates a complex that is even active in the absence of MutS at physiological ionic strength. In addition, we observed cleavage of a 109 bp linear homoduplex DNA and 2552 bp supercoil plasmid DNA at 125 mM KCl in the absence of MutS only with the crosslinked MutH/MutL complex (data not shown). However, the mechanism by which MutL activates the MutH endonuclease is not understood in detail. It has been discussed that MutL loads MutH onto the DNA and/or stabilizes the active conformation of MutH (7,8,26,52). An attractive model for stabilizing the active, closed conformation of MutH (8,53) might be the simultaneous binding of MutH between the NTD and CTD (39). At physiological salt concentration DNA-bound MutS loads MutL in an ATP-hydrolysis-dependent process on to DNA (51,54,55). Hence, MutH may be recruited to the DNA by MutL bound to MutS. A possible explanation for the MutS-independent activity of the crosslinked complex of MutH and MutL may be that upon crosslinking two MutH molecules to the MutL homodimer, the DNA-binding affinity of the crosslinked complex is enhanced. Consequently, MutS may no longer be needed to load MutL and MutH on to the DNA. Without additional data and analysis especially regarding the mode of DNA binding of MutL in the complex, a detailed mechanistic model remains speculative.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Ina Steindorf is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr George Silva for critical comment and helpful discussion. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fr-1495/3-2), the DAAD (International quality network ‘Biochemistry of Nucleic Acids’ and Personenbezogener Projektaustausch Polen D/03/44623) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF; I-SCAN; 0312834A). The Open Access publication charges for this article were waived by Oxford University Press.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunkel T.A., Erie D.A. DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schofield M.J., Hsieh P. DNA mismatch repair: molecular mechanisms and biological function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:579–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowley P.T. Inherited susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005;56:539–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.061704.135235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modrich P. Mechanisms and biological effects of mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1991;25:229–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ban C., Junop M., Yang W. Transformation of MutL by ATP binding and hydrolysis: a switch in DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1999;97:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarne A., Ramon-Maiques S., Wolff E.M., Ghirlando R., Hu X., Miller J.H., Yang W. Structure of the MutL C-terminal domain: a model of intact MutL and its roles in mismatch repair. EMBO J. 2004;23:4134–4145. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J.Y., Chang J., Joseph N., Ghirlando R., Rao D.N., Yang W. MutH complexed with hemi- and unmethylated DNAs: coupling base recognition and DNA cleavage. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ban C., Yang W. Structural basis for MutH activation in E.coli mismatch repair and relationship of MutH to restriction endonucleases. EMBO J. 1998;17:1526–1534. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall M.C., Matson S.W. The Escherichia coli MutL protein physically interacts with MutH and stimulates the MutH-associated endonuclease activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1306–1312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toedt G., Krishnan R., Friedhoff P. Site-specific protein modification to identify the MutL interface of MutH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:819–825. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giron-Monzon L., Manelyte L., Ahrends R., Kirsch D., Spengler B., Friedhoff P. Mapping protein–protein interactions between MutL and MutH by cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49338–49345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedhoff P. Mapping protein–protein interactions by bioinformatics and cross-linking. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005;381:78–80. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2892-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rappsilber J., Siniossoglou S., Hurt E.C., Mann M. A generic strategy to analyze the spatial organization of multi-protein complexes by cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:267–275. doi: 10.1021/ac991081o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trester-Zedlitz M., Kamada K., Burley S.K., Fenyo D., Chait B.T., Muir T.W. A modular cross-linking approach for exploring protein interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2416–2425. doi: 10.1021/ja026917a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for mapping three-dimensional structures of proteins and protein complexes. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/jms.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young M.M., Tang N., Hempel J.C., Oshiro C.M., Taylor E.W., Kuntz I.D., Gibson B.W., Dollinger G. High throughput protein fold identification by using experimental constraints derived from intramolecular cross-links and mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5802–5806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090099097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Back J.W., de Jong L., Muijsers A.O., de Koster C.G. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for protein structural modeling. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00721-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melcher K. New chemical crosslinking methods for the identification of transient protein-protein interactions with multiprotein complexes. Curr. Protein. Pept. Sci. 2004;5:287–296. doi: 10.2174/1389203043379701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurst G.B., Lankford T.K., Kennel S.J. Mass spectrometric detection of affinity purified crosslinked peptides. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2004;15:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and FTICR mass spectrometry for protein structure characterization. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005;381:44–47. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorman G., Prestwich G.D. Benzophenone photophores in biochemistry. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5661–5673. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorman G., Prestwich G.D. Using photolabile ligands in drug discovery and development. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:64–77. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girault S., Chassaing G., Blais J.C., Brunot A., Bolbach G. Coupling of MALDI-TOF mass analysis to the separation of biotinylated peptides by magnetic streptavidin beads. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:2122–2126. doi: 10.1021/ac960043r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julka S., Regnier F. Quantification in proteomics through stable isotope coding: a review. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:350–363. doi: 10.1021/pr0340734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng G., Winkler M.E. Single-step purifications of His6-MutH, His6-MutL and His6-MutS repair proteins of Escherichia coli K-12. BioTechniques. 1995;19:956–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loh T., Murphy K.C., Marinus M.G. Mutational analysis of the MutH protein from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12113–12119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirsch R.D., Joly E. An improved PCR-mutagenesis strategy for two-site mutagenesis or sequence swapping between related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1848–1850. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pace C.N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein? Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlin A., Akabas M.H. Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmberg A., Blomstergren A., Nord O., Lukacs M., Lundeberg J., Uhlen M. The biotin–streptavidin interaction can be reversibly broken using water at elevated temperatures. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:501–510. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaurand P., Luetzenkirchen F., Spengler B. Peptide and protein identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) and MALDI-post-source decay time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 1999;10:91–103. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(98)00145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liolios K., Tavernarakis N., Hugenholtz P., Kyrpides N.C. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) v.2: a monitor of genome projects worldwide. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D332–D334. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pei J., Sadreyev R., Grishin N.V. PCMA: fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment based on profile consistency. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:427–428. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurowski M.A., Bujnicki J.M. GeneSilico protein structure prediction meta-server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3305–3307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guindon S., Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaser F., Pupko T., Paz I., Bell R.E., Bechor-Shental D., Martz E., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf: identification of functional regions in proteins by surface-mapping of phylogenetic information. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:163–164. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosinski J., Steindorf I., Bujnicki J.M., Giron-Monzon L., Friedhoff P. Analysis of the quaternary structure of the MutL C-terminal domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:895–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deseke E., Nakatani Y., Ourisson G. Intrinsic reactivities of amino acids towards photoalkylation with benzophenone—a study preliminary to photolabelling of the transmembrane protein glycophorin A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998;1998:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Record M.T., Jr, Courtenay E.S., Cayley S., Guttman H.J. Biophysical compensation mechanisms buffering E.coli protein–nucleic acid interactions against changing environments. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedhoff P., Sheybani B., Thomas E., Merz C., Pingoud A. Haemophilus influenzae and Vibrio cholerae genes for mutH are able to fully complement a mutH defect in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;208:123–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hays J.B., Hoffman P.D., Wang H. Discrimination and versatility in mismatch repair. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2005;4:1463–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trakselis M.A., Alley S.C., Ishmael F.T. Identification and mapping of protein–protein interactions by a combination of cross-linking, cleavage, and proteomics. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16:741–750. doi: 10.1021/bc050043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinz A., Kalkhof S., Ihling C. Mapping protein interfaces by a trifunctional cross-linker combined with MALDI-TOF and ESI-FTICR mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2005;16:1921–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gygi S.P., Rist B., Gerber S.A., Turecek F., Gelb M.H., Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:994–999. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whetstone P.A., Butlin N.G., Corneillie T.M., Meares C.F. Element-coded affinity tags for peptides and proteins. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004;15:3–6. doi: 10.1021/bc034150l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Y., Bottari P., Turecek F., Aebersold R., Gelb M.H. Absolute quantification of specific proteins in complex mixtures using visible isotope-coded affinity tags. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:4104–4111. doi: 10.1021/ac049905b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junop M.S., Yang W., Funchain P., Clendenin W., Miller J.H. In vitro and in vivo studies of MutS, MutL and MutH mutants: correlation of mismatch repair and DNA recombination. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2003;2:387–405. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robertson A., Pattishall S.R., Matson S.W. The DNA binding activity of MutL is required for methyl-directed mismatch repair in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8399–8408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Acharya S., Foster P.L., Brooks P., Fishel R. The coordinated functions of the E.coli MutS and MutL proteins in mismatch repair. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:233–246. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schofield M.J., Nayak S., Scott T.H., Du C., Hsieh P. Interaction of Escherichia coli MutS and MutL at a DNA mismatch. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:28291–28299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee B.S., Krisnanchettiar S., Lateef S.S., Gupta S. Mass spectrometric detection of biotinylated peptides captured by avidin functional affinity electrophoresis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:886–892. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selmane T., Schofield M.J., Nayak S., Du C., Hsieh P. Formation of a DNA mismatch repair complex mediated by ATP. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:949–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baitinger C., Burdett V., Modrich P. Hydrolytically deficient MutS E694A is defective in the MutL-dependent activation of MutH and in the mismatch-dependent assembly of the MutS•MutL•heteroduplex complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49505–49511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landau M., Mayrose I., Rosenberg Y., Glaser F., Martz E., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]