Abstract

The KwaZulu-Natal Enhancing Care Initiative is a program developed by a consortium of members who represent 4 sectors: academia, government, nongovernmental and community-based organizations, and the business sector. The Initiative was formed to develop a plan for improved care and support for people with HIV/AIDS and who live in resource-constrained settings in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. A needs analysis helped to determine the following priorities in prevention, treatment, care, and support: training, grant-seeking, prevention, and care and treatment, including provision of antiretroviral therapy. A partnership approach resulted in better access to a wider community of people, information, and resources, and facilitated rapid program implementation. Creative approaches promptly translated research into policy and practice.

The countries that make up sub-Saharan Africa have the largest burden of HIV/AIDS worldwide.1 Most of the health care systems in this region have ranked among the 50 worst health systems in the world2 and are under significant human resource constraints, aggravated by the exodus of health care professionals to countries with more economic resources.3,4 The HIV/AIDS pandemic has most severely affected South Africa, where an estimated 6 million of its 44.8 million citizens are living with the disease (29.5% antenatal seroprevalence in 20045).

In 2000, the South African National Department of Health released the HIV/AIDS/ STD Strategic Plan for South Africa 2000–2005,6 which focused on prevention and provided a framework for a multisectoral (also known as multidisciplinary) response to HIV/ AIDS. It was only in November 2003, after prolonged controversy, that the NDoH launched the Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care and Treatment Plan for South Africa to address the wide-scale provision of antiretroviral therapy in the public sector.7–9

METHODS

A multidisciplinary and multisectoral team was assembled in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, to develop an HIV/AIDS prevention and support program. Members represented academia, government, nongovernmental and community-based organizations, people living with HIV/ AIDS, and the Durban Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The team received seed funding from the Harvard School of Public Health’s AIDS Initiative, and launched the KwaZulu-Natal Enhancing Care Initiative (ECI KZN).

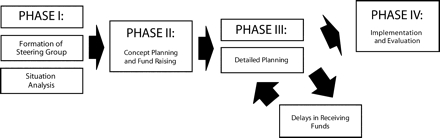

Figure 1 ▶ illustrates the process this team followed,10 which culminated in the implementation of a proposal based on the results of operational research11 and funded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM). The ECI KZN team used research to help shape policies that led to implementation of one of the largest HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support programs in sub-Saharan Africa.

FIGURE 1—

Process from acceptance of funds to implementation

Rapid assessment is a recognized practice that helps policymakers formulate new health interventions.12–14 The ECI KZN team, and KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health representatives developed an ongoing rapid assessment tool (a questionnaire) to identify the priorities in HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and support. This questionnaire was administered to 795 patients and 188 health care providers at 6 research sites, and to 220 health professionals in the private sector. A follow-up appraisal was administered to 483 public health care workers who represented more than 70 health facilities. The follow-up assessment confirmed the results of the health care providers’ evaluation beyond the original research sites. Questions covered demographics, access to care, priority needs, awareness of services, stigma and discrimination, and constraints to care. Priorities that were identified (e.g., training needs, funding, other resource needs, and drugs) (Tables 1 ▶–3 ▶ ▶), were jointly addressed and solutions to resolve them were implemented.

TABLE 1—

Survey Responses of HIV-Positive Patients Visiting Health Facilities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

| Response | |

| Average age, y | |

| Men | 32.8 |

| Women | 31.7 |

| Marriage status, % | |

| Single | 71.4 |

| Married | 20.0 |

| “Labola” paida | 96.0 |

| Average no. children with each patient | 4 |

| Lost job due to HIV/AIDS-related illness, % | 50.9 |

| Used traditional healer prior to utilizing health facility, % | 50.0 |

| Had not disclosed their HIV-positive status to anyone, % | |

| Men | 49.0 |

| Women | 36.0 |

| Not disclosed their HIV-positive status to previous partners, % | 87.5 |

| Sexually active respondents that had not disclosed their HIV-positive status, % | 61.0 |

| Person to whom HIV-positive status most often disclosed, % | |

| Mother | 43.0 |

| Sister | 42.0 |

| Most common reasons for nondisclosure, % | |

| Fear of violence | 43.0 |

| Uncomfortable talking about these issues with partner | 16.0 |

| Fearful partner would leave them | 12.0 |

| 100% adherence to current medication (self-report), % | 87.9 |

| Most common problems encountered in taking or obtaining medicine, % | |

| No problems | 71.2 |

| Side effects of medication | 10.8 |

| Financial problems | 10.7 |

| Distance traveled to obtain medication | 2.9 |

| Most common problems in accessing care, % | |

| Ignorance of care available | 28.8 |

| Not able to access facilities | 17.4 |

| Afraid of stigma | 13.0 |

| Priority needs for patients in community care, % | |

| Financial assistance | 21.2 |

| Drugs, including antiretroviral therapy | 14.5 |

| Food | 10.8 |

Note. n = 795 for all 6 sites in KwaZulu-Natal.

a“Labola” is a traditional payment made to in-laws for a wife’s hand in marriage; usually money or cows, etc.

TABLE 2—

Survey Responses of Private-Sector Health Professionals Attending a Medicines Update Session in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

| Response, % | |

| See patients who have | |

| HIV/AIDS-related diseases and who lack private insurance | 73.8 (SD = 30.4) |

| Provide referral service | 74.7 |

| Prescribe antiretroviral therapy | 56.8 |

| Attended a course in HIV/AIDS management | 66.4 |

| Top priority for private-sector health professionals | |

| Free drugs for patients | 18.5 |

| Information and education about HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral therapy | 12.3 |

| Access to counseling facilities | 7.5 |

Note. n = 146 (66.4% of sample returned surveys).

TABLE 3—

Survey Responses of Public Health Workers at 6 Health Institutions in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

| Response, % | |

| Most important area of achievement in improving access to care for patients | |

| Home-based care | 20.0 |

| Drop-in centers | 18.0 |

| Management of opportunistic infections | 17.6 |

| HIV/AIDS awareness campaigns | 14.9 |

| Involving communities | 14.9 |

| Prevention of mother-to-child transmission and all voluntary counseling and testing | 9.0 |

| Health institutions lack the capacity to deal with HIV/AIDS | 83.0 |

| Proportion of all hospital deaths perceived to be from HIV/AIDS | > 50.0 |

| Stigma and discrimination | |

| Women are stigmatized and disadvantaged | 37.0 |

| HIV+ and HIV− patients are treated the same | 54.0 |

| Women are disadvantaged in accessing health facilities | 37.0 |

| Top priority for management of HIV/AIDS | |

| Financial assistance | 35.0 |

| More staff | 27.0 |

| Training | 14.0 |

| More space | 6.0 |

| Institutional services | |

| Institution has HIV/AIDS action team | 2.1 |

| Institution provides dedicated HIV/AIDS clinic services | < 3 |

| Institution provides services for dying patients | 3.0 |

| HIV/AIDS training program is available in KwaZulu-Natal | 1.1 |

| Institution offers comprehensive care for HIV/AIDS patients | 6.0 |

| Institution lacks a training course on HIV/AIDS patient management | 96.3 |

Note. n = 188 (80% of sample returned surveys).

The ECI KZN team was able to directly influence practice and indirectly influence policy for the provision of antiretroviral therapy. The first strategy was to implement the first province-wide comprehensive HIV and antiretroviral therapy training program, which reached more than 1000 health professionals in over 50 health institutions.15,16 The second strategy was to initiate fundraising. The result of these efforts was that the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria approved a proposal entitled “Enhancing the Care of HIV/AIDS Infected and Affected Patients in Resource-Constrained Settings in KwaZulu-Natal.”17 The proposal, submitted by the ECI KZN team, included the development of a pilot infrastructure to provide antiretroviral therapy, which was not part of government policy at that time.

RESULTS

The partnerships formed by the ECI-EZN enabled the team to accomplish their goals effectively and efficiently. The involvement of stakeholders at the outset meant that programs throughout KwaZulu-Natal could be implemented and expanded soon after evaluation.18 Access to policymakers throughout the process also facilitated rapid implementation and scale-up of programs. The ECI team learned about successful projects and best practices from each other, which enabled them to obtain assistance with program implementation. Fundraising was perceived as the most difficult and most important achievement, and yet the multidisciplinary team was able to collectively obtain funds to ensure medium-term sustainability of the program. For example, one nongovernmental organization (NGO) involved in hospice and home-based care was enabled to scale up their resource-intense activities from district-wide to province-wide with additional funds and logistic support from government and academia.

Partners were privileged to be part of a team, and perceived that international collaborators, such as the Harvard School of Public Health, helped to raise the profile of their program and their contributions at a community level. In one case, an exercise to budget for scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy also helped an ECI KZN partner to prepare a successful grant proposal to the President’s Emergency Plan for HIV/AIDS. A small NGO partner linked to a rural government hospital collaborated with the local medical school and the Yale AIDS Program to provide antiretroviral therapy to tuberculosis patients undergoing DOTS (directly-observed treatment, short-course) in one of the first strategies successfully implemented in a rural district (using GFATM funds and other foundation grants).19,20 This program expanded its provincial services more rapidly than any other site in KwaZulu-Natal after the antiretroviral therapy program began. The academic team at the medical school was also able to set up one of the largest clinical HIV/AIDS postgraduate training programs in sub-Saharan Africa21 to meet the training needs of the province. Thus, the team’s priorities changed from immediate funding and training needs to provide a sustained continuing education strategy to meet ever increasing human capacity needs.

DISCUSSION

During the era of no treatment interventions, international collaboration proved critical to identifying priorities and best practices. Seed funding provided a springboard to expand successful initiatives and activities after new policies were developed (i.e., provision of antiretroviral therapy).

The opportunity to develop research tools facilitated a partnership for joint implementation of subsequent strategic initiatives. The successful proposal and unfortunate 2-year delay of the grant21 had the indirect effect of publicizing and highlighting the lack of antiretroviral drugs in public health policy, which stimulated an intensification of community mobilization to lobby government to provide antiretroviral therapy. Once the Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care and Treatment Plan for South Africa17 was approved, funds from GFATM to KwaZulu-Natal enabled the team to implement key strategies to provide a comprehensive package of prevention, care, and support, which included infrastructure for the provision of antiretroviral therapy. As of March 2006, there are over 30000 patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy in KwaZulu-Natal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Merck Company Foundation through the Harvard School of Public Health.

The authors thank Noddy Jinabhai, Raziya Bobat, Vindoh Gathiram, and Ann Strode, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; Ronald Green-Thompson, Daya Moodley, Thilo Govender, Khumbu Mtinjana, Rosemary Mthethwa, Gay Koti, Khetiwe Mfeka, Mnguni Mabuyi, Caroline Armstrong, Paul Kocheleff, Jayshree Ramdeen, and TS Makatini, Department of Health, KwaZulu-Natal, SA. They also thank field workers Zethu Gwamande (field manager), Sikhumbuza Kheswa, Philani Made, Victoria Matisilza, Nosipo Mbanjwa, Virginia Mgenga, and Marjorie Njeje.

Participants from the nongovernmental organization/ community-based organization groups were Tony Moll, Kath Defilippi, Lucky Barnabas, and Duma Shange, and from the Harvard School of Public Health were Richard Marlink and Sofia Gruskin.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors R.A. Pawinski developed and conducted the research, captured and analyzed the data, and wrote the article. U.G. Lalloo supervised and contributed substantially to the research and analysis, and assisted with reviewing the article.

References

- 1.2004 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2004. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/bangkok2004/report.html. Accessed March 06, 2006.

- 2.The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf. Accessed 06 March 06.

- 3.Raviola G, Machoki M, Mwaikaimboi E, et al. HIV, disease plague, demoralisation, and “burnout”: resident experience of the medical profession in Nairobi, Kenya. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2002;26:55–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padarath A, Ntuli A, Berthiaume L. Human Resources. In: South African Health Review 2003/2004. Cape Town, South Africa: Health Systems Trust. Available at: http://www.hst.org.za/generic/29. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- 5.National HIV and Syphilis Aantenatal Ssero-Prevalence Survey in South Africa (2004). Pretoria, South Africa: South African Department of Health; 2004. Available at http://www.doh.gov.za/aids/index.html. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- 6.HIV/AIDS/STD Strategic Plan for South Africa 2000–2005. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; 2000. Available at: http://www.gov.za/documents/2000/aidsplan2000.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- 7.Baleta A. Questioning of HIV theory of AIDS causes dismay in South Africa. Lancet. 2000;355:1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baleta A. South Africa stalls again on access to HIV drugs. Lancet. 2003;361:9360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart GT, de Harvey E, Fiala C, Hexheimer A, Kohntein K. The debate on HIV in Africa. Lancet. 2000;355:2162–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruskin S, Ayres JR, Khamranksi B, Lalloo U, Marlink R. GAVI, the first steps: lessons for the Global Fund. Lancet. 2002;360:176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pawinski RA. Developing Enabling Mechanisms to Enhance a Multi-Sectoral Response to HIV/AIDS. SA-AIDS Conference; August 3–6, 2003; Durban, South Africa.

- 12.Rhodes T, Stimson GV, Fitch C, Ball A, Renton A. Rapid assessment, injecting drug use, and public health. Lancet. 1999;354:68–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong BN, Humphris G, Annett H, Rifkin S. Rapid appraisal in an urban setting, an example from the developed world. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith GS. Development of rapid epidemiologic assessment methods to evaluate health status and delivery of health services. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4 suppl 2): S2–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawinski R. Report on the KwaZulu-Natal HIV/ AIDS Training Program, South Africa 2001/2002. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at: http://www.uKwaZulu-Natal.ac.za/eciKwaZulu-Natal. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- 16.Lalloo U, Pawinski R, Bobat R, Moodley D, Jinabhai C, Amod F, Conway S, Friedland G. A Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Training Course to Meet the Needs of Public Sector Health Care Workers in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. XVI International AIDS Conference, July 7–12, 2002; Barcelona, Spain; MoPeB3234.

- 17.Hope for South Africa—at last. Lancet. 2003; 362:501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mbali M, Pawinski R. Report on the ECI KZN PLUS Rapid Qualitative Impact Assessment. 2004. Durban, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Available at: http://www.ukzn.ac.za/eciukzn. Accessed March 6, 2006.

- 19.Gandi N, Moll A, Pawinski R, et al. Initiating and providing antiretroviral therapy for TB/HIV co-infected patients in a rural tuberculosis directly observed therapy program South Africa: the Sizonqoba study. Paper presented at: XV International AIDS Conference, July 11–16, 2004. Bangkok, Thailand; MoOrB1014.

- 20.Pawinski R, Moll T, Gandi N, Lalloo U, Jack C, Fried-land G. Strategies and Clinical Outcomes of Integrating the Provision of Antiretroviral Therapy to TB Patients Using DOTS in High TB and HIV Prevalence Rural Settings: the Sizonqoba Study. 2nd South African AIDS Conference; 7–10 June, 2005; Durban, South Africa. Abstract 490.

- 21.Pawinski RA, Pillay S, Abdool Karim Q, et al. Utilizing Video-Conference Facilities for Wide-Spread Postgraduate Clinical HIV/AIDS Training Throughout KwaZulu-Natal. 2nd South African AIDS Conference; 7–10 June, 2005; Durban, South Africa. Abstract 459. 22. Baleta A. Global Fund dispute in KwaZulu-Natal. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]