Abstract

Naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) are broadly defined as communities where individuals either remain or move when they retire. Using the determinants of health model as a base, we hypothesize that some environmental determinants have a different impact on people at different ages.

Health benefits to living within NORCs have been observed and likely vary depending upon where the specific NORC exists on the NORC to healthy-NORC spectrum. Some NORC environments are healthier than others for seniors, because the NORC environment has characteristics associated with better health for seniors. Health benefits within healthy NORCs are higher where physical and social environments facilitate greater activity and promote feelings of well-being.

Compared to the provision of additional medical or social services, healthy NORCs are a low-cost community-level approach to facilitating healthy aging. Municipal governments should pursue policies that stimulate and support the development of healthy NORCs.

THE TERM “NATURALLY occurring retirement community” (NORC) has been used since the 1980s, when Michael Hunt coined the term to describe the make-up of the apartment complexes he had surveyed in Madison, Wisc.1,2 A NORC is a community that has naturally developed a high concentration of older residents, because seniors tend to either remain in or move to these communities when they retire.2,3 NORCs exist in various forms and locations, including neighborhoods of apartments, condominiums, and single-family houses. They also exist on a spectrum, wherein the political, social, and physical environments of some NORCs are more senior friendly.

Because of the considerable role physical and social environments play in determining the health of populations, and because retirees spend more time in their communities as compared to the employed,4 it has been hypothesized that some NORC environments are healthier than others. We call them healthy naturally occurring retirement communities (healthy NORCs), and we believe they provide greater health benefits than regular NORCs because their physical and social environments have a positive impact on the health of retirees. Our operational definition of a healthy NORC is a community where environmental characteristics positively affect senior-sensitive determinants of health. The environmental characteristics enable retirees to be more physically and socially active and foster a sense of community and well-being. Merely providing additional medical or social services within a NORC does not justify a “healthy NORC” designation.

In defining a healthy NORC, we exclude the provision of additional medical services from the list of healthy NORC characteristics for 2 reasons: (1) we do not believe that medical services impact the social and physical environments in ways that will necessarily facilitate greater activity and promote feelings of community and well-being, and (2) evidence indicates that the environment may play a more important role in determining the health of populations. Healthy NORCs do not develop because of and are not influenced by seniors’ national- and state-level migration decisions, which include income tax burden, climate, economic conditions, and population characteristics.5

Demographic trends among seniors, such as living longer and wanting to “age in place” (remain in their homes as long as possible), will lead to a dramatic growth in NORCs. We believe that (1) the impact of physical and social environments on health is significant; (2) some determinants of health are more relevant for seniors; (3) there are health benefits to be gained from living within NORCs; (4) NORCs exist on a spectrum, from NORC to healthy NORC; (5) health benefits in a NORC increase as the NORC adopts additional characteristics associated with increased quality of life and better health; and (6) physical, social, and political environmental characteristics evolve as the population ages and as the local government and the private sector respond to the increased political and marketplace influence of the senior population.

The first box on the next page shows the characteristics of healthy NORCs that are in line with the determinants of health model.6 The second box shows policy options for facilitating the development of healthy NORCs and promoting healthy aging.

Characteristics of Healthy Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities.

Vibrant senior community is described by the large number of people as being physically and socially active (e.g., walking, biking, working, and socializing).

Average miles walked and number of person contacts per day are higher.

Walking access: all basic needs and amenities are within walking distance.

Walkable: clean, well-lit sidewalks and walking paths that are accessible all year.

Physical amenities have characteristics that facilitate their use (e.g., parks and paths have desirable destination points—“a reason to go”).

Presence of active community environments.

Adequate public transportation to important facilities or destination points.

Perceived as safe and crime free.

Opportunity to participate in a variety of formal and informal social and physical activities.

Community members encourage participation (results in a “healthy worker” effect for retirees).

Population density is at a level that results in regular unplanned social interaction as residents perform their activities of daily living.

Local governments experience high levels of participation by seniors and see increased numbers of seniors in elected or appointed positions.

Local governments progressively demonstrate senior-friendly policy decisions.

Private sector markets progressively respond to the needs of seniors.

Healthy Naturally Occurring Retirement Community Policy Initiatives.

Keep sidewalks well maintained, lighted, and clear of snow.

Look for ways to make streets and intersections more pedestrian friendly and safe.

Increase the duration of time for yellow and green periods of traffic lights and increase the size of street signs.

Implement measures that decrease the speed and frequency of automobile traffic.

Evaluate, develop, and implement active community environment policies.

Add walking and bicycle paths that include points of interest (destination points).

Add new parks, maintain existing parks, and increase the number of park benches or tables.

Improve children’s play facilities.

Add bicycle lanes and allow nonlicensed, personal electronic vehicles or golf carts to use these lanes.

Change residential zoning restrictions to allow seniors walking-distance access to needed goods and services (e.g., health clinics, pubs, supermarkets, and shops).

Evaluate public transportation and consider shuttle buses to points of interest or facilities, such as malls or hospitals.

Lobby state or provincial governments for step-down driving license laws that permit elderly seniors to drive longer (e.g., licenses restricted to daytime or local driving).

Implement a policy that supports private sector involvement and ability to address senior needs.

Implement property tax concessions for seniors.

Provide incentives for private sector investment (e.g., relaxation of urban planning restrictions).

Support community-based nongovernmental organizations that address seniors’ interests.

Facilitate senior participation in municipal government activities (i.e., look to seniors as a new source of part-time civil servants). This includes both creating employment opportunities for seniors and looking to seniors as a source of knowledge and labor.

Promote senior-led volunteerism.

Increase the perception of security by making police presence a part of the community.

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS

Demographic trends are important to public health planning and policy: as trends change, policy should change so that the needs of communities with specific characteristics are met. Current demographic trends, combined with the desire to age in place, will lead to a dramatic growth in NORCs. Thirteen percent of Canada’s 32 million people are aged 65 years or older; it is estimated that this proportion will rise to 21.4% by 2031.7 The United States will see a similar increase: it is estimated that the senior population will increase from 35 million in 2000 to 70 million by 2030.8,9

Along with the trend in aging is a global trend toward urbanization. The United Nations predicts that the percentage of urban dwellers will increase from 47% in 2000 to 60% by 2030.10,11 Much of this increase will be attributed to the aging population; in Canada, 80% of seniors are currently living in cities. Trends indicate that seniors are returning to the city, and they are returning because of increased access to services and recreational amenities in urban settings, a desire to avoid the isolation associated with rural living, and decreased functioning (e.g., health status, physical ability, disability).12–15

Evidence also shows that seniors want to age in their homes. In a 2000 AARP study, 79% of the 2001 respondents aged 50 years and older indicated that they wanted to remain in their homes as long as possible. This desire increases with age.8,16–18 Similar results were obtained in a 1997 Angus Reid poll of 1515 Canadian adults, 80% of whom indicated a preference to die at home versus dying in a hospital or other care facility.19

In light of these trends, it is logical that most NORCs have developed in cities. For example, in New York City it is estimated that 400 000 of the city’s 1.25 million seniors live in NORCs; nationwide, there are more than 5000 urban NORCs (total population >10 million) in existence.20,21 Thus, the growth of NORCs is likely to continue and therefore warrants considerable public health policy attention, particularly at the municipal level.

ENVIRONMENT AND HEALTH

Medical Care, the Environment, and Health

In our symposium presentation, we stated, “the environment is what allows us to maintain our state of health. We rely on health care when genetics and our environmental or social policies have failed us.”22(p1) This statement was used to facilitate a discussion about the determinants of health and the need, particularly for government, to allocate more attention to the environment rather than the traditional focus on health care services.23,24 However, health care remains a much more prominent political topic that is more frequently reported on in the media and discussed in political settings. One commonly discussed issue focuses on the ways in which the aging population will impose serious stresses on the health care system. Driving this discussion is the belief, often promoted by system stakeholders, that medical care is important to the health of the population. Proponents argue that stresses on the health care system—such as the aging population and the high level of resources consumed by seniors—will ultimately result in poorer overall access to services and will consequently have a negative effect on population health.

This medicine-and-health-care debate persists despite the large body of research that suggests that physical and social environments may play the most important role in determining the health of populations.5,25–29 According to Guyatt, “Getting old doesn’t by itself mean increased use of health resources. What causes increased health utilization is illness.”30(pA-11) Guyatt also suggests that health care costs for the elderly are strongly associated with disability. Evidence shows that the elderly not only are living longer and experiencing lower rates of disability but also are more active, healthier, and more prosperous than previous generations.7,9,23 If this trend continues, there will be fewer ill or disabled seniors consuming health care resources than projected, which will result in a smaller than anticipated impact on the health care system. Research conducted in British Columbia supports this assertion.31

Evans argued that clinical medicine has played a limited role in advancing overall population health.32 This does not mean that modern medicine lacks impact. However, it does imply that the main determinants for the overall population are found elsewhere in the social and physical environments.23 For example, in England and Wales, between 1848 and 1901, there were rapid declines in overall mortality rates from infectious disease (92%) before the widespread use of antibiotics and other effective medical therapies.33

According to Jackson, “We now realize that how we design the built environment may hold tremendous potential for addressing many of the nation’s greatest current public health concerns.”34(p1382) This potential can be seen in a 2000–2002 study of 10500 Atlanta-area residents, which showed the impact of local environment on health, by finding that land-use mix was strongly associated with obesity. Each kilometer walked per day by a resident was associated with a 4.8% reduction in the likelihood of obesity, whereas each hour a resident spent commuting was associated with a 6% increase.35 This study presented one of the earliest reports of an association between the urban automobile-oriented environment and an adverse health outcome such as obesity. Community characteristics can affect overall health by influencing physical activity; however, the built environment also can affect social capital, mental health, exposure to hazards, and unintended injuries.36 Thus, it is also reasonable to expect that community characteristics can affect levels of stress.

Environment, Stress, and Health

How do environmental characteristics affect health, and which characteristics are particularly important for seniors? These questions are relevant to healthy aging because chronic (or lifestyle) conditions, such as cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, and some cancers, have replaced infectious diseases as the primary causes of morbidity and mortality.37

Chronic stress and the subsequent physiological and psychological coping mechanisms used by different populations are important determinants of future health.29,32,38–40 Research shows the importance of life experiences in programming “competent or self-damaging” responses to future stresses. Evans argued that there is “a biological pathway from social environment to health status, operating through the stress response system. While that system is highly adaptive in itself, prolonged and unresolved stresses can lead to physiological changes that may be harmful.”32(p51)

This biological pathway is believed to operate at the hormonal level of a hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to prolonged stress. An increase in glucocorticoid hormones is associated with an elevated stress response, which then decreases other important energy-consuming activities. Because of the stress, the body stays in the “fight or flight” mode longer. This in turn inhibits immune competence and other important long-term anabolic processes, such as growth, tissue repair, and bone recalcification.41 Prolonged stress may render an individual less healthy because of an inhibited ability to counteract the causes of morbidity.

Evidence also suggests that perception of environment plays an important role within the long-term stress response system. Associated with an increased stress response are individual perceptions of instability, decreased control, and a lack of social supports, which partially explains why some disadvantaged populations experience higher morbidity and mortality rates.32,41

A 3-year randomized study on the effects of beta-blockade on coronary events showed the association between chronic stress and health. The study found that those who were classified at the beginning of the study as being both socially isolated and highly stressed had mortality rates 4- to 5-fold higher than those who were not isolated and were less stressed.42 In another study, Holtgrave and Crosby used 1999 surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to explore the association between tuberculosis, poverty, income inequality, and social capital, and they found social capital was the strongest predictor of lower tuberculosis rates.43 Thus, we hypothesize that an elevated stress response system is strongly affected by perceptions of control (more control means less stress), and this perception is partially dependent on both social capital and unstable environments.24 An individual has a greater sense of control in a more stable environment where social capital is adequate.

Are Some Determinants of Health More Relevant to Seniors?

In clinical medicine, it has long been recognized that people need to receive different medical treatments at different stages of life. Therefore, it is appropriate to argue that nonmedical determinants of health also affect people differently during different periods in life. For example, if seniors’ stress response systems are continuously active over prolonged periods of time because of stressors that have a greater impact on seniors, the result is likely to be more illness among seniors.

What characteristics of the environment then, when combined with retirement and aging, can invoke and prolong the stress response system and thus lead to physiological changes that may be harmful to the health of seniors? The answer may be associated with increased stress caused by perceptions of loss of control. It also may be associated with decreases in the protective effects of adequate physical and social activities.23,44 Examples of stress-provoking characteristics associated with retirement include changes that affect income and financial security, social circles, relocation, leisure, physical and mental health and abilities, isolation, health insurance and access to health care, and new freedoms and dependencies. It is reasonable to expect that these changes will be associated with varying degrees of stress.

Municipal policy can also impact seniors’ health by raising stress levels. One example is a decision by Toronto officials to reduce budget expenses by eliminating or reducing sidewalk snow-plowing in some areas.45 Compared to employed adults, retirees spend more time in the community and, as their age increases, are less likely to have access to automobiles. Thus, the possible effects of this policy on seniors include (1) increased anxiety or stress because of fear of slipping and falling; (2) increased anxiety associated with concerns about their ability to walk the distance over snow; (3) decreased social and physical activity and the loss of associated protective health benefits; (4) increased isolation, (5) decreased access to adequate nutrition, food, or shopping; and (6) decreased sense of control over daily activities. Anything that has an impact on physical activity may be particularly important to seniors. For example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicated that older people are at higher risk for inactivity-associated health problems and that few factors contribute as much to successful aging as having a physically active lifestyle.44 Thus, even if the biological pathway from the environment to health status does not exist, simple barriers to physical and social activity are likely to have a different impact on the health of seniors.

THE NORC-TO-HEALTHY-NORC SPECTRUM

NORCs assume many different economic, social, physical, and environmental characteristics. However, they ultimately feature qualities that are particularly accommodating to the seniors who live within them, the most important of which is ease of access to goods and services.2

NORCs may evolve into healthy NORCs as the elderly population grows and as the local government and the private sector respond to the growing population. A NORC can travel along the healthy NORC spectrum independently of its residents’ relative wealth, provided the residents have physical and economic access to basic needs and are not living in a state of poverty.32 Therefore, the physical environment may be the most important characteristic that facilitates the evolution from NORC to healthy NORC. It can provide opportunities for developing vibrant social and physical environments that also provide a sense of community—a clean, safe, secure, and socially welcoming interactive residential area. The primary difference between a NORC and a healthy NORC is the unavoidable sense that a healthy NORC resident feels drawn into a vibrant active community.22

Because NORCs can develop within all communities, and because the local environment affects health, it is logical to assume that any given NORC could be more or less healthy for seniors depending upon the senior-sensitive characteristics of their environment. Travel along the healthy NORC spectrum is associated with the local-level (i.e., community-level) adoption of healthy NORC characteristics that are believed to provide positive health benefits. The ability of a specific community to adopt such changes is affected by local policy. Thus, municipal governments play an important role in facilitating the evolution of NORCs along the NORC-to-healthy-NORC spectrum.

What Makes a NORC Healthier?

Municipal governments are well positioned to make a NORC healthier, because community environment affects residents’ health. For example, municipal governments can make policy that (1) promotes physical activity, by changing zoning laws to increase walking distance access to goods and services, and (2) promotes social activity, by improving characteristics of parks or other public gathering places. The community environment–resident health association cannot be explained simply by looking at community variations in socioeconomic status.46,47 Seniors spend more time in their community, so it also is likely that their health is more sensitive to community characteristics (similar to a dose–response relationship).4 Examples of characteristics associated with seniors’ health include barriers to physical activity, social arrangements and relevant community-level policies, a sense of neighborhood or feeling of belonging, and exposure to neighborhood problems and communitywide stressors.48–51

Thus, a NORC can be made healthier by changing characteristics to increase activity, decrease stress, and provide a sense of community and well-being. In England and Sweden, positive health changes were reported after simple changes were made to the physical environment, such as closing alleyways, decreasing the speed and frequency of automobile traffic, and improving recreation facilities.52 Generally, the changes must embrace the basic needs of residents. They also should encourage healthy behaviors, recreational activities, social interactions, and community involvement. Exposures to hazards and potential for injury should be minimized. The important components of the social environment may develop as a result of the physical environment. Thus, to some degree, we argue that if the built environment has the physical characteristics seniors want and need, they will stay or migrate to it, and they will then move the NORC along the healthy NORC spectrum.

The characteristics of healthy NORCs exist on a spectrum, with mature healthy NORCs possessing additional features associated with increased quality of life and improved health for seniors (Table 1). As healthy NORCs mature and seniors’ influence increases, both local governments and the private sector will respond in ways that are more senior friendly.53,54

Policy Options That Facilitate Development of Healthy NORCs

Although all levels of government policy respond to demographics, municipal policy is the most critical. In the United States, protecting the public’s health is a basic responsibility of local governments.25 Thus, the local factors (social, physical, and political) play a major role in supporting healthy NORC development. Obrist suggested that governments can act to protect citizens from environmental hazards and social, economic, and political insecurity, all of which will support healthy NORC development.10 Governments should evaluate policies that affect residential and business zoning, parks and recreation, transportation, public health, public safety, health services facilities, private sector investment, employment, and taxation.

How costly and politically feasible is it for a municipality to implement changes that facilitate the development of senior-friendly communities and that help NORCs travel along the healthy NORC spectrum? It may be less costly than many think. Compared with increasing health care or social services, developing healthy NORCs is a low-cost approach to facilitating healthy aging. Table 2 lists policies that should be considered.

If a municipality is interested in implementing a healthy NORC policy that responds to the needs of the growing senior population, officials should understand that the goal of the collective policies is to facilitate increased physical activity and social interaction and to provide a sense of community and well-being. The result will be the creation of a healthy community, which Dannenberg defined as one that “protects and improves the quality of life for its citizens, promotes healthy behaviors and minimizes hazards for its residents, and preserves the natural environment.”36(p1500) Because the characteristics of the physical environment may be what led to the initial NORC development, the changes to the built environment that are required for a healthy NORC may not be extensive and may only require improved access or additional amenities. Thus, many of the policy options that could promote the development of a healthy NORC would be more dependent on the political process and less dependent on funding or on residents’ socioeconomic status.

CONCLUSIONS

Public health can be improved by identifying and making somewhat simple changes to modifiable community-level characteristics. NORCs exist on a spectrum—from NORC to healthy NORC—depending on the collective characteristics of their physical, social, and political environments. A NORC may evolve into a healthy NORC as the elderly population grows and thus increases its political and marketplace clout. The local government and the private sector will respond in ways that are associated with increased quality of life and improved health for seniors. Compared with the provision of health care services, the healthy NORC policies we have suggested are a low-cost approach to facilitating healthy aging. Health care is expensive, and costs continue to rise. For example, the Canadian government has legislated incremental cash transfers to provinces and territories for health and social programs, which represent an increase of $1.8 billion per year from 2003 to 2008 that will total $28.1 billion by the end of the agreement—an average annual growth rate of 8% in federal support.55,56 Health care spending in the United States is projected to follow a similar path, with an annual growth of 7.3% through 2013.57

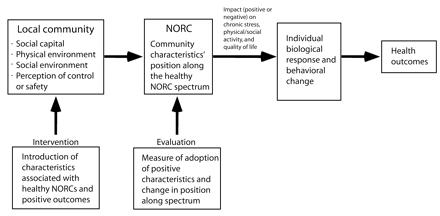

The policy implications of encouraging healthy NORCs are time sensitive and comprehensive. Understanding the impact of community-level physical and social environments on the health of seniors is important. Future research must include investigating the senior-sensitive determinants of health associated with healthy NORC characteristics and evaluating politically and economically feasible approaches to facilitating the development of healthy NORCS within different geographic and socioeconomic status settings. Possible research methods include (1) identifying measurable differences between healthy NORCs and NORCs, (2) evaluating proxy variables associated with seniors’ health outcomes, (3) implementing geographic information system approaches, (4) conducting community-level quasi-experimental studies, (5) conducting multilevel analyses, and (6) testing community-based interventions that import healthy NORC characteristics into NORCs (Figure 1 ▶).26,36,58–60 Further research will improve municipal governments’ ability to respond to the aging population, including the development of low-cost approaches to facilitating healthy aging.

FIGURE 1—

Community-based healthy naturally occurring retirement community (healthy NORC) interventions and impact on position along the healthy NORC spectrum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ronald Masotti and Jennifer Ranford for their contributions and suggestions to earlier versions of the article.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors P.J. Masotti originated the idea of healthy NORCs. R. Fick conducted much of the literature searches and wrote several sections of the article. A. Johnson-Masotti edited and restructured significant sections the article. S. MacLeod served as a mentor and made significant changes to the last draft of the article.

References

- 1.Perry J. For most, there’s no place like home. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/usnews/biztech/articles/010604/aging.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 2.Hunt ME, Gunter-Hunt G. Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities. J Housing Elderly. 1985;3:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senior Resource Web site. What is aging in place? Available at: http://seniorresource.com/ageinpl.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 4.Roux AV, Norrel LN, Haan M, Jackson SA, Schultz R. Neighbourhood environments and mortality in an elderly cohort: results from the cardiovascular health study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:917–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncombe W, Robbins M, Wolf DA. Place characteristics and residential location choice among the retirement-age population. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:s244–s252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. In: Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TL, eds. Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994:27–64.

- 7.Statistics Canada. Population projections for 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 and 2026. Available at: http://www.statcan.ca/english/pgdb/demo23c.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 8.Schuetz J. Affordable Assisted Living: Surveying the Possibilities. Cambridge, Mass; Harvard University, Joint Centre for Housing Studies, 2003.

- 9.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans 2000: key indicators of well-being. Available at: http://www.agingstats.gov/chartbook2000/highlights.html. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 10.Obrist B, Van Eeuwijk P, Weiss M. Health anthropology and urban health research. Anthropol Med. 2003;10: 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Secretariat. World urbanization prospects. The 2001 revision. ESA/P/WP. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wup2001/wup2001dh.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 12.Roseman E. Don’t overlook the downside of country living. Toronto Star. May 2004:C1–C2.

- 13.Pope E. Voting with their feet, boomers head back to the city. Available at: http://www.aarpmagazine.org/lifestyle/articles/a2004-07-22-mag-suburban.html. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 14.Longino CF, Jackson DJ, Zimmerman RS, Bradsher JE. The second move: health and geographic mobility. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1991;46:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graff TO, Wiseman RF. Changing pattern of retirement counties since 1965. Geogr Rev. 1990;80:239–251. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwald M. These four walls . . . Americans 45+ talk about home and community. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/research/reference/publicopinions/aresearch-import-769.html. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 17.Rosel N. Aging in place: knowing where you are. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;57:77–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers A, Raymer J. Immigration and the regional demographics of the elderly population in the United States. J. Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001; 56:44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirby MJ. The health of Canadians: the federal role. Available at: http://www.cpa.ca/kirbyopa.pdf. Accessed Marcy 27, 2006.

- 20.United Hospital Fund of New York research and programs. Available at: http://www.uhfnyc.org/homepage3219/homepageshow.htm?docid=97871. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 21.Lagnado L. Old notions: all-natural retirement isn’t so easy, a look at the belnord shows—in a luxury building, a duel between senior services and a landlord’s vision—the symbolism of benches. Wall Street Journal. July 3, 2001:A1.

- 22.Masotti P. Healthy-NORCs. Paper presented at: Symposium 2004; October 16, 2004; Orangeville, Ontario.

- 23.World Health Organization (WHO). Active Aging: A Policy Framework. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002

- 24.Lomas J. Social capital and health: implications for public health and epidemiology. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson RJ, Kochtitzky C. Creating a Healthy Environment: The Impact of the Built Environment on Public Health. Washington, DC: Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse; 2001.

- 26.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeman TE, and Crimmins E. Social environmental effects on health and aging: integrating epidemiologic and demographic approaches and perspectives. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;954:88–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavis J, Stoddard G. Social Cohesion and Health. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University, Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis; 1999. Working Paper Series #99-09.

- 29.Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Consuming research, producing policy? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt G. Elderly are not going to sink our health care system. Hamilton Spectator. August 9, 2002:A11.

- 31.Evans RG, McGrail KM, Morgan SG, Barer ML, Hertzman C. Apocalypse now: population aging and the future of health care systems. Available at: http://socserv2.mcmaster.ca/~sedap/p/sedap59.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 32.Evans RG. Interpreting and Addressing Inequalities in Health: From Black to Acheson to Blair to. . . ? London, UK: Office of Health Economics; 2002.

- 33.McKeown T. The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 1979.

- 34.Jackson RJ. The impact of the built environment on health: an emerging field. Am J Public Health. 2003;93: 1382–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank LD, Anderson MA, Schmidt TL. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dannenberg AL, Jackson RJ, Schieber RA, Kochtitzky C. The impact of community design and land-use choices on public health: a scientific research agenda. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1500–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease prevention: chronic disease overview. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 38.Suomi SJ. Biological, maternal, and lifestyle interactions with the psychosocial environment: primate models. In: Hertzman C, Kelly S, and Bobak M, eds. East-West Life Expectancy Gap in Europe: Environmental and Non-Environmental Determinants. Norwell, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996:133–142.

- 39.Coe CI. Psychosocial factors and psychoneuroimmunology within a lifespan perspective. In: Keating, Hertzman, eds. Developmental Health and the Wealth of Nations: Social, Biological, and Educational Dynamics. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999;10:201–219.

- 40.Suomi SJ. Developmental trajectories, early experiences, and community consequences: lessons from studies with rhesus monkeys. In: Keating DP, Hertzman C, eds. Developmental Health and the Wealth of Nations: Social, Biological, and Educational Dynamics. Guilford Press; 1999;9:185–200.

- 41.Sapolsky RM. hormonal correlates of personality and social contexts: from non-human to human primates. In: Panter-Brick C, Worthington CM, eds. Hormones, Health, and Behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1999:18–47.

- 42.Ruberman W, Weinblatt E, Goldberg JD, Chaundhary BS. Psychosocial influences on mortality after myocardial infarcation. New Engl J Med. 1984;311:552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holtgrave D, Crosby R. Social determinants of tuberculosis case rates in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity and older Americans: benefits and strategies. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/ppip/activity.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 45.City of Toronto Works and Emergency Services. Transportation services—winter maintenance services. Mechanical sidewalk snow clearing, window clearing, and laneways. Available at: http://www.city.toronto.on.ca/budget2004/pdf/westra2wintermaintenanceedited.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 46.Ellaway A, Macintyre S. You are where you live. Evidence shows that where we live has a significant impact on our mental health. Ment Health Today. 2004;Nov:33–35. [PubMed]

- 47.Bassuk SS, Berkman LF, Amick BC Ill. Socioeconomic status and mortality among the elderly: findings from four US communities. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 155:520–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher KJ, Li F, Michael Y, Cleveland M. Neighborhood-level influences on physical activity among older adults: a multilevel analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2004;12:45–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leviatan U. Contribution of social arrangements to the attainment of successful aging—the experience of the Israeli Kibbutz. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young AF, Russell A, Powers JR. The sense of belonging to a neighbourhood: can it be measured and is it related to health and well being in older women? Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:2627–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steptoe A, Feldman PJ. Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curtis S, Cave B, Coutts A. Is urban regeneration good for health? Perceptions and theories of the health impacts of urban change. Environ Plann C Government Policy. 2002;20:517–534. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swauger K, Tomlin C. Best Care for the elderly at Forsyth Medical Centre. Geriatr Nurs. 2002;23:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Keeffe J. Creating a senior friendly physical environment in our hospitals. J Can Geriatr Soc. 2004;7:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Department of Finance of Canada. The importance of health. 2004. Available at: http://www.fin.gc.ca/budget04/pamph/paheae.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 56.Department of Finance of Canada. Moving forward on the priorities of Canadians—the importance of health. 2004. Available at: http://www.fin.gc.ca/budget04/bp/bpc4ae.htm. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 57.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2003 expected to mark first slowdown in health care cost growth in six years. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/media/press/release.asp?counter=961. Accessed June 21, 2005.

- 58.Craig WJ, Harris TM, Weiner D. Community Participation and Geographic Information Systems. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2002.

- 59.Librett JJ, Yore MM, Schmid TL. Local ordinances that promote physical activity: a survey of municipal policies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1399–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diez-Roux A. Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:171–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]