Abstract

Geographic assessments indicate that the selection of produce in local supermarkets varies by both area-level income and racial composition. These differences make it particularly difficult for low-income African American families to make healthy dietary choices. The Garden of Eden produce market was created to improve access to high-quality, affordable produce for these communities.

The Garden of Eden is housed in a church in an economically depressed African American community in St Louis, Mo, that has less access to fresh produce than surrounding communities. All staff are from the community and are paid a living wage. The market is run with an eye toward sustainability, with partners from academia, a local faith-based community organization, businesses, and community members collaborating to make all program decisions.

AS OBESITY REACHES epidemic proportions in the United States, we are faced with the challenge of intervening to effect change. Public health practitioners recognize that to reduce community obesity rates, it is critical to first understand the determinants of obesity and then intervene to change these determinants. To date most of the public health interventions to decrease obesity have focused on 2 of the known determinants of obesity—eating behaviors and physical activity—because obesity is associated with a caloric intake greater than caloric expenditure.1 Most of these interventions have focused on creating changes in individual behavior through education. However, public health practitioners are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of social, economic, and physical environmental influences on health and health behaviors, including those behaviors leading to obesity.2–4

Previous work evaluating the role of social and environmental factors on eating patterns has discovered important associations. For example, Swinburn et al.2 suggested that the availability of grocery stores and fast-food restaurants as well as factors such as transportation systems create more or less “obesogenic environments,”2(p564) which in turn influence community-level rates of obesity. Others have found that the availability of healthy foods influences the consumption of foods.5,6 Some researchers have also begun to examine the impact of social determinants, such as racial composition of a community and area-level socioeconomic characteristics, on the availability and consumption of various foods. For example, it is less expensive to shop in large or chain grocery stores.7 Lower-income and minority communities have been found to have fewer supermarkets, providing them with less access to healthy choices.5 Thus, it appears that having a supermarket within a certain geographic area combined with a selection of fruits and vegetables within the store influences consumption, and that not all economic and racial groups have equal access to these supermarkets. Although there has been research focusing on the determinants of eating patterns, few studies have incorporated this information into an intervention.

Our study builds on this previous body of work by incorporating an understanding of the various social, economic, and physical environmental factors (social determinants of health) into the development and implementation of an intervention program aimed at increasing fruit and vegetable consumption.

PROGRAM INITIATION

Our project was a result of collaboration between faith-based health advocates, lay church members (facilitated by Inter-faith Partnership’s Abraham’s Children), and academics that began in 1999 in St Louis, Mo, and continues to the present. The collaboration began with discussions of the association between faith and health and the various ways in which faith communities could get involved with their communities to create changes in community health. In the process of these discussions, the group identified some of the most critical health concerns facing the communities in the areas surrounding their churches. Obesity and related diseases were identified as being of great concern. The health advocates noted that in order to combat obesity within their communities, it was essential not only to provide information about nutrition and physical activity but also to create the infrastructures (e.g., supermarkets with a large selection of high-quality fruits and vegetables) to enable people to make healthy choices. Moreover, they recognized that the availability of these infrastructures is intricately tied to the social context within which people live. In other words, racial and economic disparities, or social determinants of health, influence infrastructures, which in turn influence opportunities to make healthy choices. This process was reflected in the fact that most of the supermarkets in the urban areas around the churches had closed and that those that were left had a smaller variety (or selection) of food choices than stores in the surrounding area. An assessment (geographic and qualitative) of the association between social and economic factors and the selection of produce that had been conducted as part of a separate project (described in the next section) was reviewed to learn more about these associations and determine next steps for intervention.

SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS INFLUENCING EATING BEHAVIORS

Geographic Assessment

The geographic assessment was part of an earlier study, Prevention in Context, that examined how social and community factors influenced the efficacy of a dietary change program, High 5–Low Fat. High 5–Low Fat was conducted in partnership with Parents as Teachers and was designed to influence dietary changes within an urban African American population8 (all participants in this study were African American). One aspect of the study was to increase participants’ consumption of fruits and vegetables. Eight High 5–Low Fat sites were used as part of the current study to assess the extent to which the supermarkets in these areas provided access to a selection of various fruits and vegetables so that the program participants could increase their consumption of produce.

In order to assess the selection of various types of food available at local supermarkets (i.e., selection of fruits and vegetables, meat, chicken, dairy), audits were conducted in all supermarkets that were identified by the 2000 business census as being either supermarkets or major chain supermarkets and having addresses that were geographically located within the 8 program sites. Because the availability of produce was a primary concern of health advocates in the program, we focus on that.

There is nothing in the literature recommending that stores have a specific variety or minimal selection of fruits and vegetables to enable people to make healthy choices. We therefore used the USDA’s Continuing Survey Food Interview Initiative to identify the types of fruits and vegetables consumed within Midwestern cities. Information on the selection of these fresh, frozen, and canned fruits and vegetables available at the stores within the 8 sites was collected through supermarket audits. Each store was audited by 2 people: 1 observer (who noted all the items observed), and 1 recorder (who checked the item off on a checklist). The auditors used a checklist of 78 different fruits and vegetables (on the basis of the Continuing Survey Food Interview Initiative) and checked whether or not each store carried that fruit or vegetable and if it was available fresh, frozen, or canned. Each supermarket then received a score on the basis of the number of different fruits and vegetables available. For example, if a store carried fresh, frozen, and canned peaches, it would receive a score of 3 for peaches. The total number of fruits and vegetables available was then summed for each store.

For the purposes of this study, sites were categorized on the basis of the mean number of fruits and vegetables available for all supermarkets in each site. Audits of all stores were conducted over a 6-month period. The mean number of fruits and vegetables at all stores (across the 8 sites) ranged from 65.47 to 124.40. On the basis of the data’s distribution, we categorized the mean number of fruits and vegetables available into tertiles; 82.06 or less total fruits and vegetables was considered low, 82.07 to 107.07 was considered medium, and 107.08 or greater was considered high.

Area-level income and racial composition of the community sites were reviewed to ascertain their relation to selection of fruits and vegetables. Area-level income was defined as the median household income on the basis of the 2000 US Census data for the zip codes constituting each of the sites. The median household income was then aggregated to the site level. Less than $30 000 was considered low, $30 000 to $40 000 was considered medium, and greater than $40 000 was considered high (on the basis of the distribution of the data). Racial composition was also on the basis of 2000 US Census data. If 50% or more of the population was 1 race (African American or White), that race was considered the majority, whereas 49% or less of 1 race was the minority. Analyses were also conducted to evaluate the combined effect of racial composition (African American, mixed, White) and income.

Geographic information systems software allows the user to assign attributes to a geographic unit and to show the relation between pairings of variables for these units. In order to determine the association between the previously mentioned variables, we used ArcGIS (ESRI, Redlands, Calif) to geocode supermarkets and to map each store within the appropriate site. Area-level income and race were mapped by aggregating the zip codes contained within each site. Each site was then categorized into tiers (e.g., high, medium, or low income) for each of the attributes of interest (selection of fruits and vegetables, area-level income, racial composition).

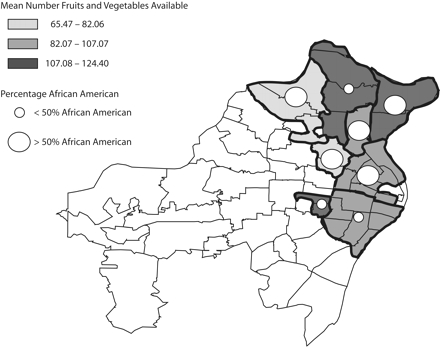

Figure 1 ▶ shows the association between the selection of fruits and vegetables and racial composition. Sites that were majority (50% or more) African American had fewer supermarkets that offered a large selection of fruits and vegetables than sites that were majority White. Of the 3 majority White sites, 2 sites had high selection, 1 medium, and 0 low selection. In comparison, of the 5 majority African American sites, 1 site had stores with high selection, 2 medium, and 2 low selection.

FIGURE 1—

Selection of fruits and vegetables and racial composition of area.

Note. Racial/ethnic composition from 2000 US Census data.

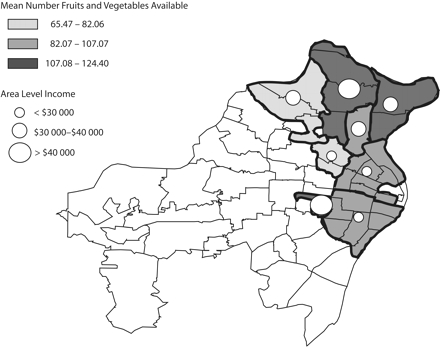

Figure 2 ▶ illustrates the association between the selection of fruits and vegetables and area-level income. The selection of fruits and vegetables was highest in sites with the highest income and tended to decrease as area-level income decreased.

FIGURE 2—

Selection of fruits and vegetables and area-level income.

Note. Income levels from 2000 US Census data.

When we looked at racial composition as primarily White (> 75% White), primarily African American (> 75% African American), and mixed sites (25% to 75% White or African American), the results were similar in that those areas that were primarily African American had less selection than those that were primarily White. Mixed racial sites had less selection when they had lower area-level income and more selection when they had higher area-level income (data not shown).

Qualitative Assessment

In order to understand the social and community factors that influence eating patterns and the ability to change eating patterns, Prevention in Context also included group and individual qualitative interviews with High 5–Low Fat program participants and the lay health advisers who delivered the program.9 In these interviews, the participants indicated that they often experienced racism and discrimination when they patronized supermarkets in primarily White areas. These stores were also quite a distance away, making it difficult to get to them, particularly because of the limited public transportation available. Participants also noted that the stores in primarily African American areas had fewer produce and low-fat options and did not have “no-candy lanes” (seen as particularly important for parents with small children). They also said they wanted someone at the store to provide information about the food choices they could make and how to prepare foods in a healthier way. When asked about good places to implement these programs, the participants noted that churches were important and trusted institutions within their African American communities and have historically been places where many community members have gone to obtain, and share, the most important information of the day.

FROM ASSESSMENT TO INTERVENTION

The data obtained from the Prevention in Context study supported the health advocates’ views that the infrastructures within their communities did not afford them the opportunity to make healthy choices. In particular, they saw that there was a shortage of supermarkets in their communities, and that existing stores had an inadequate quality and quantity of fruits and vegetables. The Garden of Eden was therefore started to provide a variety of high-quality affordable produce to these communities as well as to create community infrastructures and supports to enable people to make healthy choices. The faith-based health ministries collaborated with academic and business leaders (including Saint Louis University and Saint Louis Produce Market) to help bring the ministries’ ideas to fruition and to obtain funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One main aspect of the Garden of Eden program was the development of a community-run produce market located in a local church. A church was chosen to house the market in response to suggestions made by community members. The Garden of Eden was located in a part of the city that had primarily African American residents, where there was low area-level income, and where we found a low selection of fruits and vegetables in local markets. Transportation was provided to the store from local churches and senior centers. In addition, health advocates (local community members) provided supportive nutritional information and cooking demonstrations within the store, at their churches, and in other community settings (e.g., libraries). The health advocates determined the recipes that would be used at these demonstrations, focusing on recipes that had a few affordable ingredients, all of which were available at the Garden of Eden or local supermarkets (the Garden of Eden was a produce market and did not carry many other items).

Items Sold at the Store

Previous community studies and the supermarket audits indicated that although community members were beginning to reach consumption of 5 fruits and vegetables a day, most of what was available and consumed was of lower nutritional quality. We used the US Department of Agriculture’s Continuing Survey Food Interview Initiative to determine the fruits and vegetables that would have the greatest potential for change, that is, those that were consumed but at a lower than optimal rate. For example, community members ate sweet potatoes and broccoli but would have benefited nutritionally from increased consumption of these vegetables. Community health advocates and the store manager also assisted in identifying which fruits and vegetables community members typically ate, for example, turnip, collard, and mustard greens, and these items were also selected to be sold at the store.

Underlying Structure

The project was designed to maximize sustainability and community ownership. As stated by the Rev Lynn Mims, the pastor at the hosting church, “Too many projects come into poor communities and do research and never leave anything behind. We got involved because this effort is different” (personal communication, 2003). In order to maximize the potential for sustainability, all educational materials were created so that they could be reproduced relatively inexpensively, and the produce itself was priced so that it was affordable, yet the price enabled the market to eventually be able to generate enough money to pay store staff. The intent was to leave not only a viable and effective project to increase the opportunity to make healthy choices, but also to leave the community with a business that would enable community members to have part-time, meaningful employment. A commitment was made to pay all staff a livable, rather than minimum, wage. This was unique among part-time jobs available in the community.

In order to maximize sustainability, it was also critical that the community own this effort. Therefore, all project decisions were made collaboratively with input from health advocates (lay community members) and community and academic partners, including how money was spent, who was hired for what positions, and how and what data were collected and reported back to the community. Health advocates met with community and academic partners to jointly decide the content of the health education messages, as well as the best ways to deliver them. For example, health advocates and academic and community partners met monthly to determine the content and wording of health education messages highlighting the importance of fruit and vegetable consumption and decreasing fat consumption (e.g., February—Honor your heart, health, and heritage). Health advocates then conveyed these messages through church bulletin boards, testimonials, and sermons, as well as at presentations at church-related programs (e.g., Bible study) and local community organizations (e.g., senior centers and libraries).

DISCUSSION

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies that have shown that individual-level knowledge and skills as well as social determinants including the physical environment (e.g., access to fruits and vegetables at the supermarket) and social contextual factors (area-level income and racial segregation) influence health and health behaviors.2–4 Thus, as stated by James,10 in order to eliminate health disparities, we cannot focus solely on individual behaviors. It is important to recognize that disparities in obesity, for example, are also associated with disparate access to the structures necessary to make healthy choices. The Garden of Eden acknowledged these factors in its design, implementation, and evaluation. We did this, for example, by creating decisionmaking processes that do not mimic traditional power structures and by creating economic opportunities in an area that most other businesses had abandoned.

Limitations and Lessons Learned

The Prevention in Context study was initiated to examine the extent to which participants in a dietary change program had access to the fruits and vegetables required for the dietary changes they were being asked to make. Thus, program sites were chosen for the unit of geographic assessment rather than more standardized geographic units such as census block or census tract. However, aggregating to any geographic area reduces the ability to discern more detailed and specific influences of the environment on community and individual health at lower levels of aggregation. Future studies may want to consider using multilevel modeling with area aggregation at different levels. With these methods, future studies may be better able to determine the specific level of selection of produce that is required to enable people to make healthy choices and thereby provide some direction for recommendations and policy development.

The Garden of Eden began as the result of academics and members of the faith community taking the time to be together and learn from each other outside specific grant-funded programs. This helped to build a relationship on the basis of mutual trust and respect. Although trust and respect are critical factors in community-based participatory research, they take time to build. It is often difficult to spend this time because of the partners’ institutional requirements. We also found that doing this work takes a personal commitment to “put things on the table” and to listen to others. This can be particularly challenging in working across not only faith and academic communities but also business communities. Different people have different perceptions of the benefits of the group process and collective decisionmaking and different value bases that all need to be taken into account in a faith-and community-based business endeavor. We also found that although we needed to first develop good working relationships among our administrative team, we also needed to remind ourselves that the community members themselves must own the project. This has at times presented additional challenges: the processes and decisions of all partners have not always been consistent. We continue to work on improving our communication patterns and sharing our perspectives because we recognize that working together we can create better outcomes than working alone.

Next Steps

The Garden of Eden’s produce market is up and running efficiently every week. We are now working diligently to expand the customer base at the store and our educational efforts in churches and other community settings by increasing community outreach activities. In addition, we have begun to explore the factors influencing physical activity through interviews with community members and have started initializing programs in this community that address these factors. Last, we are completing our analysis of our data (including that related to diet and physical activity). We will present our data to several community forums to begin dialogues on the influence of social determinants on the infrastructures available for community members to make healthy choices. It is our hope that this process will engage various partners in creating change.

Acknowledgments

Support was obtained from the American Cancer Society (grant TURPG-00-129-01-PBP) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant R06/CCR721356).

The authors also acknowledge D. Haire-Joshu, M. S. Nanney, H. Harvey, C. Hughes, J. Betts, M. Kanu, and H. Vo for their contributions to the projects and data collection described.

Human Participant Protection Human subject approval for this study was received from the Saint Louis University institutional review board.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors E.A. Baker, C. Kelly, E. Barnidge, D. Griffith, M. Schootman and J. Struthers all assisted with data collection and geographic assessments. All authors contributed equally to originating the article, interpreting findings, and developing and reviewing drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science. 1998;280:1371–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swinburn B, Egger F, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29(6 pt 1):563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French S, Story M, Jeffery R. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:309–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacIntyre S, Maciver S, Sooman A. Area, class, and health: should we focus on places or people? J Social Policy. 1993;22:213–233. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Curry S, et al. Community-level comparisons between the grocery store environment and individual dietary practices. Prev Med. 1991;20:250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung C, Myers S. Do the poor pay more for food? An analysis of grocery store availability and food price disparities. J Consum Aff. 1999;33(2): 276–296. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haire-Joshu D, Brownson RC, Nanney MS, et al. Improving dietary behavior in African Americans: the parents as teachers High 5, Low Fat program. Prev Med. 2003;36(6):684–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker E, et al. Access, Income and Racial Composition: Dietary Patterns Aren’t Just a Personal Choice. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; 2003; San Francisco, Calif.

- 10.James S. Confronting the moral economy of US racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93: 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]