Abstract

Chains of Care are today an important counterbalance to the ever-increasing fragmentation of Swedish health care, and the ongoing development work has high priority. Improved quality of care is the most important reason for developing Chains of Care. Despite support in the form of goals and activity plans, seven out of ten county councils are uncertain whether they have been quite successful in the development work. Strong departmentalisation of responsibilities between different medical professions and departments, types of responsibilities and power still remaining in the vertical organisation structure, together with limited participation from the local authorities, are some of the most commonly mentioned reasons for the lack of success. Even though there is hesitation regarding the development work up to today, all county councils will continue developing Chains of Care. The main reason is, as was the case with Chain of Care development up to today, to improve quality of care. Although one of the main purposes is to make health care more patient-focused, patients in general seem to have limited impact on the development work. Therefore, the challenge is to design Chains of Care, which regards patients as partners instead of objects.

Keywords: integrated care, Sweden, chain of care development, effectiveness of care, patient empowerment

Introduction: Chains of care provide structure to fragmented health care

During the last few years almost all Swedish county councils have supported the development of Chains of Care.1 To elucidate and improve the most common Chains of Care, and to manage health care more from a horizontal perspective, is today an important counterbalance to the ever-increasing fragmentation of health care [1]. This in turn is an effect of three major driving forces in health care development. Firstly, decentralisation has gone so far that Swedish health care could be classified as frontline-driven, i.e. ward sisters and other frontline managers have extensive responsibilities and far-reaching authority to act independently.

A second trend of significance is the sub-specialisation in health care. This is mainly due to medical development, whereby health care personnel acquire in-depth medical knowledge in an ever-decreasing area. This leads to diminished knowledge of closely related specialities among health care personnel, and as a logical consequence of this to a better understanding that improved health care not always requires better professions but better systems of work [2]. A system in this sense is a set of elements interacting to achieve a shared aim.

Finally, we have the principle of a professional organisation [3]. In health care, physicians, nurses, and other personnel independently take decisions regarding the treatment of patients, and they take personal responsibility for those decisions. In this kind of organisational culture, aiming for common health care goals has low priority; instead the focus is on treatment of the problems the patient is seeking help for.

All three factors, individually and together, have strongly contributed to the autonomous functions of today's health care. This entails difficulties in the coordination of activities for patient treatment, if they are to be carried out in several different functions, since it is rare to have one single person with responsibility for the entire treatment process and corresponding decision-making power.

The fragmentation effects of these driving forces largely explain the growing interest in Integrated Care and the development of Chains of Care in Swedish health care. In some cases this has taken place in a spontaneous way, while other health care organisations have a more strategic and well-planned development of their Chains of Care. We have also examples of health care organisations, like the Region of West Götaland, preparing themselves for management systems that, to a considerable degree, emanate from Chains of Care [4]. The importance of the traditional line organisation will thereby diminish.

With this background in mind we found it important to increase the knowledge about the state of art, the history and the expectations of Integrated Care in the future, and particularly the development of Chains of Care. Are they expected to be cornerstones in future Swedish health care organisations, and if so, what is going to drive the development of our health care system to be more integrated?

Method

The results of this study are based on data from a survey carried out by Solving Bohlin & Strömberg. This was sent out to all county councils in Sweden2 during spring 2002. The survey was mailed to the Directors of Health and Medical Services in the county councils. The purpose, i.e. our research questions, was described in a covering letter accompanying the questionnaire. A person with an overview of the county council was requested to answer the questions and return the questionnaire in a pre-stamped return envelope3. After a round of reminders, 19 of the 21 county councils answered the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 91%.

Our ambition with the survey was to obtain answers to the following research questions about Integrated Care in Sweden.

How extensive is the development of Chains of Care?

What is the main motive for developing Chains of Care?

What are the most common patient categories among current Chains of Care?

What are the critical success factors? Are there traps to avoid?

How common is it to go from development projects to a systematic and radical adaptation of management systems that emanate from Chains of Care?

What about the future development of Chains of Care? Is Chain of Care only a buzzword or have Chains of Care come to stay in Swedish health care?

Definition

In this survey Chain of Care was defined as “coordinated activities within health care, linked together to achieve a qualitative final result for the patient. A Chain of Care often involves several responsible authorities and medical providers” [6].

In other words a Chain of Care shall include all health care provided for a specific patient group within a county council. A Chain of Care shall incorporate health care produced by the local authorities within the catchments area of the county council in question. A patient flow limited to treatments within a hospital or a primary care centre is by definition not a Chain of Care.

It is important to stress that Chains of Care are based upon evidence-based health care4 and clinical guidelines, i.e. agreements on distribution of medical work, within a county council area, between different providers of health care.

Results

Chains of care have high priority

Developing Chains of Care to improve the integration of care has high priority in Swedish health care. More than two of three county councils answer that they have clearly formulated goals, activity plans or other policy documents supporting the development of Chains of Care. The rest of the county councils answered that they have ongoing development work, but there is no manifest support in these kind of documents. Accordingly there is ongoing Chain of Care development in all-Swedish county councils. Almost half of the county councils have had goals, activity plans, etc. for the last 3–5 years, and one in three county councils compiled this kind of document more than five years ago.

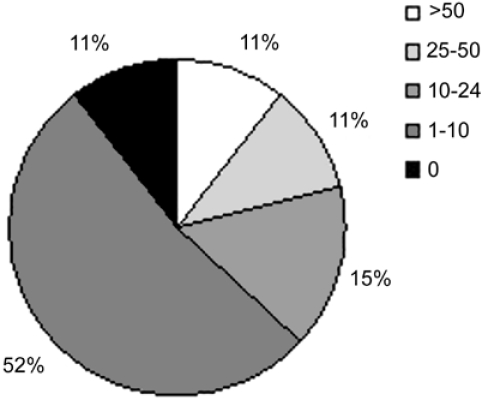

Over half of the county councils have developed 1–10 Chains of Care during the last five years (see Figure 1). County councils with the shortest experience of Chain of Care development, i.e. when goals, activity plans, etc. are at most two years old, all belong to this category. The group of county councils that only have developed up to ten Chains of Care are also represented by those who have prioritised Chains of Care for more than five years. The fact that some “old-timers” have developed only a relatively small amount of Chains of Care is explained by the respondents mainly as “lack of knowledge and understanding of the importance of co-ordinating health care activities carried out in units outside one's own”. In other words despite the support by goals and activity plans, development work in reality has a low priority. In three county councils the development efforts have not yet led to the establishment of Chains of Care. Instead the focus has been on elaborating forms for general collaboration with health care providers in the local authorities and drawing up guidelines for care collaboration.

Figure 1.

Number of developed Chains of Care per county council during the last five years.

The two largest county councils, with more than 1.5 million inhabitants and over 40,000 employed personnel, are the only ones that have developed more than fifty Chains of Care. The interval 25–50 developed Chains of Care consists of two county councils. One of them is the third largest county council with 1.1 million inhabitants and 30,000 employees. One of the medium-sized county councils has the largest number of Chains of Care per 100,000 inhabitants. The smallest county council, with only 0.05 million inhabitants, has developed twice as many Chains of Care per 100,000 inhabitants as the two largest county councils. Furthermore, no correlation could be found between the numbers of developed Chains of Care and:

the number of hospitals in the county council

type of management system, for example purchaser and provider models

Instead the analysis shows that the most important factor to explain the number of developed Chains of Care is the duration of the development work. County councils with the shortest experience all belong to the category with 1–10 developed Chains of Care. County councils with a high number of developed Chains of Care have promoted the development work for more than five years.

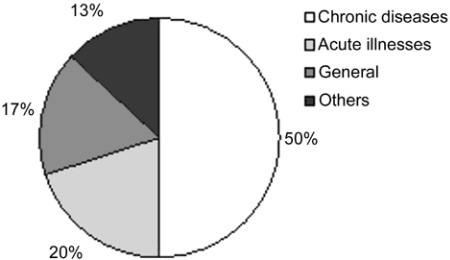

The respondents had to place their Chains of Care into the four predetermined categories exemplified in the questionnaire. Patients belonging to a particular Chain of Care are characterised by having the same illness or symptom. Chronic diseases are generally labelled with a specific diagnosis. Chains of Care for patients with acute illnesses are preferably named according to the symptoms experienced [1]. So, instead of calling a Chain of Care “acute myocardial infarction” it is more appropriate to name it “chest pain”. The general group especially contains Chains of Care that focus on collaboration between the county council and the local authorities. Cancer, palliative care and anorexia are examples of ill-health in the general group.

Figure 2 illustrates that half of all developed Chains of Care contain different kinds of chronic diseases, for example diabetes, dementia and rheumatism. The answers to the questionnaire demonstrate that the county councils with the smallest amount of experience in Chain of Care development, i.e. those who have developed only a maximum of ten Chains of Care, have developed relatively more Chains of Care in the general patient group (22%). On the other hand, they have a lower portion (19%) in the group with acute illnesses. Whether this is due to an initial deliberate prioritisation of patient groups with general problems with ill health, or if it is generally believed that it is easier to develop Chains of Care for patients with, for instance, infirmity of old age, cannot be interpreted from the answers. No corresponding discrepancy occurs when different Chains of Care are related to short experience, i.e. county councils with goals, activity plans, etc. that are at most two years old.

Figure 2.

Developed Chains of Care distributed by patient category.

The opportunity to improve the quality of care is the most important reason for developing Chains of Care (see Table 1). This primarily concerns structural and process quality [8], i.e. factors that have an effect on, for instance, the design of health care organisations and performance in everyday activities. Outcome quality is seldom a primary reason for developing Chains of Care.

Table 1.

Reasons for developing Chains of Care in order of precedence

| Reason | Order of precedence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Improved quality of care | 76 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Rationalised operation | 18 | 47 | 24 | 0 |

| Participation of patients | 6 | 18 | 53 | 0 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

Development work is making slow progress

The county councils had to answer whether they regard themselves as successful in developing Chains of Care according to the definition of our study. We did not ask for proofs such as improved outcome, reduced costs, etc. The focus of the study was instead on the work of designing and implementing Chains of Care. The result shows that seven out of ten county councils are uncertain whether they have been quite successful in developing Chains of Care in this sense. Strong departmentalisation of responsibilities between different medical professions and departments, together with obstacles in types of responsibilities and power still remaining in the vertical organisation structure, are some of the most commonly mentioned reasons for the uncertainty. Preliminary evaluation results from the implementation of MCNs in Scotland indicate problems with similar obstacles [9]. Furthermore, half of the county councils answer that they have not had regular participation from the local authorities in the development work, and this decreases the possibilities of developing Chains of Care that include all activities from the start to the finish of a treatment process.

Until today, no county council has made significant changes in its management systems due to the Chain of Care development. Four out of ten county councils answer that they have made minor changes. In three of ten county councils this involves some cases where a purchaser organisation has bought health care for a whole Chain of Care, instead of making a traditional purchase of bed days, operations, consultations, etc. from different health care providers.

County councils who consider themselves successful in developing Chains of Care do not differ from other county councils as regards, for instance:

- Experiences of Chain of Care development

- Number of years the development work has been running

- Number of developed Chains of Care

The presence of structural obstacles, such as separate authorities for primary care and hospital care

Type of management system; purchaser-provider models or traditional plan-budget models

The only variable with a divergent result concerns whether the county council has “clearly formulated goals, activity plans or other documents supporting the development of Chains of Care”. All county councils with success stories in Chain of Care development, with the exception of one, answered, “yes” to this question. The real significance of this needs a deeper analysis than is possible to do on data from this survey.

Chains of care are here to stay

Despite hesitation regarding the development work up to today, all county councils answer that they will continue developing Chains of Care (see Table 2). “Rationalised operations” and “participation of patients” are both considered to have increased importance compared to previous development work, but the main reason is, as was the case with Chain of Care development up to today, to improve quality of care.

Table 2.

Reasons for continuing Chains of Care development in order of precedence

| Reason | Order of precedence |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Improved quality of care | 58 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Rationalised operation | 26 | 32 | 26 | 0 |

| Participation of patients | 16 | 16 | 42 | 0 |

| Others | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

One out of three county councils with the longest experience of Chain of Care development (with more than five years of formulated goals, activity plans or other policy documents supporting the development work) state that “participation of patients” is the main reason for future development of Chains of Care. In the group of county councils with the shortest experience (with a maximum of two years of supporting documents) no one put this reason in first place. Instead six out of ten county councils in this group state, “rationalised operations” as the main reason for future Chain of Care development. This is compatible with the present order of precedence regarding the reasons for Chain of Care development in this group of county councils, see comments on Table 1.

Discussion

What is distinctive about chains of care?

Outcome quality is taken into account in the relatively few cases where Chains of Care principally support the implementation of new or improved medical guidelines for specific patient groups. In this respect the Swedish development work partly differs from international experiences. For instance, in the UK one of the main objects of working with Integrated Care Pathways, or Protocol-based Care as NHS Modernisation Agency in England choose to call them, is to reduce unnecessary variation in practice and thereby reduce the risk of malpractice [10]. According to the NHS Modernisation Agency in England, the development of Protocol-based Care addresses the key questions of “what should done, where, when and by whom” [11]. This is achieved by the support of care protocols, which describes in detail routine procedures for specific patient groups. A care protocol is in turn built on national standards and evidence-based guidelines.

Management Clinical Networks (MCN) in Scotland, defined as “linked groups of health professionals and organisations from primary, secondary and tertiary care, working in a co-ordinated manner, unconstrained by existing professional and Health Board boundaries, to ensure equitable provision of high quality clinically effective services” [12], are one example of a near equivalent to Chains of Care. MCNs operate across institutional and other boundaries and they challenge existing budgetary flows and capital planning processes [13]. The focus on services and patients, rather than upon buildings and organisations, corresponds to the core principles of Chains of Care.

Rationalisation of operations is not the main reason for developing Chains of Care (see Table 1), and this in turn is explained by the fact that the development work has its origin in the general efforts at quality improvement that have taken place in Sweden, supported among other things by the Swedish quality improvement tool QUL (Quality, Development and Management) [14]. Even though the development work in the mid-1990s was inspired by Business Process Re-engineering and other rationalisation tools, today quality improvement has become the most important reason for developing Chains of Care. In that respect there is a difference between Sweden and, say, Denmark, where a corresponding developments drive, “Patient Logistics”, is mainly regarded as a method for improving the utilisation of health care resources [15].

The relatively few county councils that consider rationalisation to be the main reason for the development work are over-represented in the group with the shortest development experience. Three of four county councils in this category state this as the reason why they are developing Chains of Care. It is not possible to interpret from the answers whether this is some kind of revival for Chain of Care development as a rationalisation tool in health care, or if the quality aspects become more important the longer the county councils persevere with Chain of Care development.

The strong focus on quality improvement makes it possible for the county councils to reduce poor quality costing, i.e. rationalise the operations due to improved quality. These two reasons for developing Chains of Care are in that sense interacting, even though the rationalisation driving force is disputable, as it seems hard to find clear evidence of increased process efficiency or improved cost by integrating health care providers with the aim to benefit patients [16].

Why is the development work making slow progress?

Experience has shown that it takes at least six months to develop a Chain of Care [6]. This fact, and a short period of promoting development work, gives the best explanation for the small number of developed Chains of Care compared with other characteristics of the county councils. The factors to explain high numbers of developed Chains of Care probably have to do with several years of continuous successful development by overcoming inter-organisational obstacles. Experiences from process development demonstrate when managers are able to elucidate and animate common goals and visions, and when they do so in a consistent way, the power of penetration increases [6, 17, 18]. Whether this is also the case in the successful county councils, or whether other factors are of significance, remains to be proven.

In spite of some success-stories, the results shows that a large majority of the county councils are uncertain whether they have been successful in the development work. Strong departmentalisation of responsibilities and vertical power-structure are main reasons for the slow progress. Another reason could be resistance among health care managers. In Sweden we have some cases where the health care personnel were eager to develop more Integrated Care, for instance between primary care and health care in the local authorities, but they did not get backing from their managers due to fear of changing the established working routines and the health care organisation [19].

Six out of ten county councils have in one or some cases appointed a Chain of Care Manager (CCM) with responsibilities for follow-up and continuous development. Several policy documents recommend this procedure. Nevertheless, only one county council has consistently appointed a CCM for every developed Chain of Care, and this in turn indicates above that is difficult to carry on with continuous development and make sure that the work does not end with just a few projects. In the long run it is desirable to give CCMs power that matches that of managers in the vertical structure (head of wards, departments, etc.). A first step in that direction could be to re-allocate development and education grants for a specific Chain of Care from managers in the vertical structure to the CCM in charge [1].

Can existing values be changed by a top-down approach?

A disharmony between the values of the health care personnel and the overall goals, activity plans, etc., for the whole health care organisation leads to a low priority in Chain of Care development. Strong management, based on an enlightened vision, has proven to be an effective factor for successful process development in industry [17, 18]. The Mayo Clinic is a good practice in health care where the top management's credo strongly influences day-to-day work. At Mayo Clinic, the patient comes first, and they explicitly and systematically hire people who genuinely embrace the organisation's value system [20]. In Swedish health care, we have some good practices in county councils which where able to make substantial cost rationalisations driven by county directors of finance [21]. But when it comes to Chain of Care development, not limited patient flows within a hospital, there are only a few examples of success. The question is whether the common value system of the health care professionals is too strong, and will also remain so in the future, to be influenced by top-down instructions? A negative response to top-down quality control is perhaps expected given evidence from Health Maintenance Organisations in the USA, with physicians being angered over their loss of authority and autonomy. Similar reactions can be found in the modernisation of the English health care system and its centrally developed quality standards. Quality-driven NHS is seen as laudable, but the method of implementation has not yet provided sufficient conditions or incentives for the deliverers of care to become successful in the modernisation process [22]. Thence it follows that managing the balance between corporate governance and local autonomy seems to be the biggest challenge implementing integrated care [23].

The fact that three of ten county councils regard themselves as successful in Chain of Care development may be interpreted as an argument in favour of a top-down approach. It is difficult, however, to find clear answers from the survey as to what kind of successes these county councils really have had. For instance, is it possible that top management in the county councils have an overoptimistic interpretation of the development work? Have strong leadership and enlightened communication regarding what to achieve by Chain of Care development led to substantial success? Ability to translate the Chain of Care concept so it makes sense in every-day life has proven to be a key success factor [24]. Could this be one of the explanations for the declared success? These are questions that remain to be answered.

Are the patients able to change professional values?

All Chain of Care development work has in principle been initiated by hospital or county council management and been driven by handpicked health care personnel. Sometimes, but in far from all cases, patients' views have been collected by eliciting information from patient inquiries, focus groups, hearings, etc. Although one of the main purposes is to make health care more patient-focused, patients in general seem to have limited impact on the development work. There are lots of examples where suggestions are put forward with the intention of facilitating things for the patients [6], for example by concentrating various resources in one working unit and carrying out different procedures on one single occasion. This has been done with the good intention of making it easy for the patients, but the development work so far has been producer-driven, and the solutions might have been different with a patient-driven development process.

In the Swedish debate, nowadays, it is common to hear arguments claiming that health care ought to be better prepared for a growing health care consumerism [1, 25] characterised by empowered patients [26, 27] who are integrated in health care processes. Perhaps this growing development force will have a greater impact on the reform of Swedish health care, compared with the existing goals and activity plans produced by politicians and top management? A breakthrough for health care consumerism could mean that existing values in health care, which mainly rest on professional value systems, will be fused with demands emerging from consumer behaviour. Goals concerning patient-focused Chains of Care will perhaps not be generally realised until articulated patient demands are channelled in this way to health care personnel, and as a logical consequence of that create a change in their value system.

Conclusions

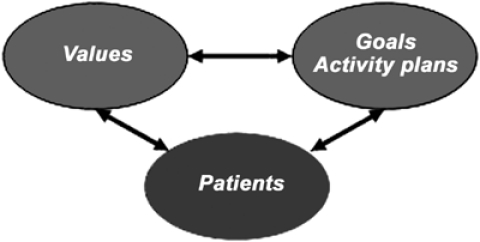

An unambiguous conclusion is that Chains of Care are expected to be cornerstones in future Swedish health care. What, then, can we learn from the successes and mistakes of development work up to now? One of the most essential weaknesses is the fact that seven out of ten county councils are uncertain as to whether they have been successful so far in their Chain of Care development. Among the reasons mentioned for the uncertainty one can find: departmentalisation of work, perceived challenge to the existing power structure, weak incentives for collaboration and no redistribution of power to CCM. This indicates the difficulties health care managers have in gaining a hearing and achieving penetration for goals and visions, if they do not correspond to the personal values influencing how the everyday tasks are carried out. As in the case of MCNs in Scotland one of the biggest challenges is to reconcile hierarchical accountability with cross-boundary working [9]. Harmony and concordance between the values of the health care personnel and goals, activity plans, etc. create opportunities to develop organisational efficiency. But this is not enough since effectiveness of care also needs to be a result of activities creating something useful for patients and relatives. This connection is illustrated, as a free adaptation of Selznick's theory of distinctive competence [28] to health care, in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effectiveness of care is influenced by three interacting elements.

According to some researchers values for the customer are not created by the service provider, but by the customers themselves [29, 30]. Resources, processes and competences should be considered as inputs into customers' processes and support for customers' value creation. Even though health care is a complex service provider and to a large extent differs from general service providers, this thesis demonstrates the importance of delivering services, which are regarded as useful by the patients.

The values of the health care personnel are a key success factor in Chain of Care development. As a project leader of several Chain of Care projects, it is the author's experience that the value-based resistance is stronger among physicians than among other health care personnel. A low level of physician-system integration corresponds with results from a health integration study carried out by Shortell and associates [31]. The non-physician group often manifest greater interest in and enthusiasm for Chain of Care development. This can probably be explained by the fact that this category of health care personnel also, in general, has shown a greater interest in quality improvement supported by the above quality tools, which in turn is the main reason for developing Chains of Care.

One way of being pro-active and preparing health care for active health care consumers could be to involve patients right away in health care processes, i.e. Chains of Care [32]. There is a growing body of evidence that patients who take an active role in managing their care have better health outcome [33]. Dedicated patients will also be important change agents of the professional value system and the willingness among health care personnel to improve integration between different health care providers. Therefore, the challenge is to design Chains of Care, which regards patients as “contributors” [29] and partners [34], and not objects, in treatment procedures, in other words, to set up Integrated Care not only within the existing health care delivery system, but also with the integration of the patients.

Footnotes

Methods Section contains a definition and a general description of the term Chain of Care.

The Swedish health care system has two main responsible agents: 21 county councils and 289 local communities. They all have their own directly elected parliaments. The right to self-government is stipulated in the Instrument of Government of the Constitution of Sweden. This states that the county councils and local communities have the right to levy taxes in order to finance their work. Today, approximately 70% of the county councils are financed by county council taxes, which on average is just over 10% of the taxable income [5].

In some county councils the survey was sent on to local health care districts to obtain more valid answers.

The English-language literature distinguishes between evidence-based health care (scientifically based decisions concerning health care) and evidence-based medicine (scientifically based decisions concerning an individual patient) [7]. In this case evidence-based health care is the most proper translation.

Vitae

Based on his research and experiences from assignment regarding Integrated Care Bengt Åhgren has written the book “The Chain of Care” Vårdkedjan, Studentlitteratur, ISBN 91 44 01265 9

References

- 1.Åhgren B. Chains of care: a counterbalance to fragmented health care. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways. 2001;5:126–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berwick D. Medical associations: guilds or leaders. British Medical Journal. 1997;314:1564–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7094.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mintzberg H. The structuring of organizations. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The health care board of Region West Götaland. Budget 2002 and plan for 2003–2004 (in Swedish) Skövde: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) [Online] Available from: URL: http://www.skl.se/artikel.asp?C=756&A=180.

- 6.Åhgren B. The chain of care (in Swedish) Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi R. Evidence-based health care (in Swedish) Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander H, Macdonald E. The art of integrated multi-disciplinary partnership working: are there people who just don't want to play?; Paper presented on UK Evaluation Society Annual Conference; 2002 December 12–13; London. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Luc K. Developing care pathways – the handbook. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Modernization Agency [Online] Available from: URL: http://www.wise.nhs.uk/cmswise/default.htm.

- 12.The Scottish Executive. Introduction of managed clinical networks in Scotland. Department of Health. Management Executive Letter, MEL (99) 10. Edinburgh: St Andrews's House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods K. The development of integrated health care models in Scotland. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2001 Jun 1;1 doi: 10.5334/ijic.29. Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Federation of County Councils. Criteria and instructions for quality, development and management 1997/98 – a tool for health care development (in Swedish) Stockholm: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen LO. Patient Logistics (in Danish) DSI Infoark. 2001;3:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan TTH, Ma AMS, Lin BYJ. Integration and the performance of healthcare networks: do integration strategies enhance efficiency, profitability and image? International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2001 Jun 1;1 doi: 10.5334/ijic.31. Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall G, Rosenthal J, Wade J. How to make re-engineering really work. Harvard Business Review. 1993 Nov-Dec;:119–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zairi M. Leadership in TQM implementation. Total Quality Management Magazine. 1994;6:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjöberg M. Resistance against networking Chain of Care (in Swedish) The Department of Social Science, Mid Sweden University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry L, Bendapudi N. Cluing in the customers. Harvard Business Review. 2003 Feb;:100–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svalander PA, Åhgren B. What should we call what has taken place in Mora? – and other questions about management systems (in Swedish) Stockholm: The Federation of Swedish County Councils; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin N. Creating an Integrated Public Sector? Labour's plans for the modernisation of the English health care system. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2002 Mar 1;2 doi: 10.5334/ijic.48. Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray R, Henderson J, Johnson J. Implementing integrated care pathways across a large, multicentre organisation: lessons learned so far. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways. 2001;5:36–140. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindberg K. The power of connecting, or organizing between organizations (in Swedish) Kungälv: Bokförlaget BAS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borgenhammar E, Fallberg LH. Dare to be a care consumer: ways to consciousness (in Swedish) Stockholm: SNS; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Åsberg KH, Molin R, Stattin U. New and old patients (in Swedish) Stockholm: The Federation of Swedish County Councils; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordgren L. From patient to costumer. The arrival of market thinking in health care and the displacement of the patient's position (in Swedish) Lund: Lund Business Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selznick P. Leadership in administration. Evanston, Ill.: Row Peterson; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin B, Normann R. Opportunity of care (in Swedish) Stockholm: Ekerlid förlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grönroos C. Marketing theses in the age of customer relationships: servicizing the customer relationship to support customers' value processes. Forum on Service Management, Tianjin University of Commerce; 2002. Oct 10, [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA, Mitchell JB, Morgan KL. Creating organized delivery systems: the barriers and facilitators. Hospital and Health Services Administration. 1993;38(4):447–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Åhgren B. IKEA values in health care will empower the patients (in Swedish) Medicine Today. 2001;11:49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wold-Olsen P. The customer revolution: the pharmaceutical industry and direct communication to patients and the public. Eurohealth. 2003;5:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership? Patients have grown up – and there's no going back. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:719–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]