Abstract

Purpose

PRISMA is an innovative co-ordination-type Integrated Service Delivery System developed to improve continuity and increase the efficacy and efficiency of services, especially for older and disabled populations.

Description

The mechanisms and tools developed and implemented by PRISMA include: (1) co-ordination between decision-makers and managers, (2) a single entry point, (3) a case management process, (4) individualised service plans, (5) a single assessment instrument based on the clients' functional autonomy, and (6) a computerised clinical chart for communicating between institutions for client monitoring purposes.

Preliminary results

The efficacy of this model has been tested in a pilot project that showed a decreased incidence of functional decline, a decreased burden for caregivers and a smaller proportion of older people wishing to be institutionalised.

Conclusion

The on-going implementation and effectiveness study will show evidence of its real value and its impact on clienteles and cost.

Keywords: health services for the aged, integrated service delivery systems, frail elderly, programme evaluation

Although the problem of continuity applies to and is significant for all health care and services, it is particularly acute at the present time in regard to the frail elderly. Many factors—demographic (accelerated ageing of the population), social (break-up of families, children moving away to find work), economic (low income women living alone), health (increased life expectancy, high incidence of disabilities) and financial (reduced health care budgets)—are putting strong pressure on both the demand for and the supply of services for this clientele. Functional decline generates an increased need, for both the dependent individuals and their families, for evaluation, treatment, rehabilitation, psychological and social support, help to remain at home, and temporary or permanent long-term care facilities [1]. These multiple needs can also change quickly over time due to the biological, psychological and social vulnerability of this frail clientele. In terms of supply, a wide range of resources and services involving numerous practitioners and partners have been developed over the past twenty years to try to meet these needs. However, continuity-related problems compromise both service accessibility and the efficiency of health care services. For example: multiple entry points, service delivery which is influenced by the resource contacted rather than the user's need, numerous redundant evaluations of clienteles not using standardised tools, inappropriate use of costly resources (e.g. hospitals, emergency services), waiting time for services, inadequate transmission of information, and the piecemeal response to needs [2–4]. In a situation where resources are scarce and the demand for services is increasing, it is essential to ensure that the services meet the users' needs, without duplication and as efficiently as possible. Therefore, there is an urgent need to provide managers and decision-makers with reliable data on the process and impact of mechanisms and tools designed to improve the continuity of care and services and to establish a monitoring system so that it is possible to adapt quickly and effectively to changes in the demand for services. Last but not least, these mechanisms and tools could subsequently be adapted to care and services for other clienteles that also present continuity problems (e.g. mental health, young people with physical and/or intellectual disabilities).

Continuity refers to the organised, co-ordinated and steady passage of individuals through the various elements in a system of care and services [5]. It comprises two aspects: the short-term aspect (synchronic) relates to the application of an intervention and concerted, co-ordinated service plan over a given period; the long-term aspect (diachronic) relates to monitoring and harmonising intervention and service plans over a protracted period. This later aspect has also been called “longitudinality” by Starfield [6].

Integrated Service Delivery (ISD) programmes have been developed to improve continuity and increase the efficacy and efficiency of services, especially for older and disabled populations. Kodner and Kyriacou define integrated care as “a discrete set of techniques and organisational models designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors at the funding, administrative and/or provider levels” [7]. According to Leutz, there are three levels of integration: (1) linkage; (2) co-ordination; and (3) full integration [8].

The three levels of integrated service delivery

At the linkage level, organisations may develop protocols to facilitate referral or collaboration to deal with patients' needs. However, the organisations continue to function within their respective jurisdictions, responsibility and operational rules. In Canada, since the health care system is universal and mainly publicly funded, there are already many initiatives and programmes in the health care system that integrate services at the linkage level.

At the other end of the spectrum, the full integration level, the integrated organisation is responsible for all services, either under one structure or by contracting some services with other organisations. Many examples of this level of ISD programmes have been developed. In the United States, the California On Lok project [9] gave rise to the PACE (Program of All inclusive Care for the Elderly) projects [10]. In Canada, the CHOICE (Comprehensive Home Option of Integrated Care for the Elderly) project in Edmonton is an adaptation of the PACE projects [11]. These programmes are built around Day Centres where the members of the multidisciplinary team who evaluate and treat the clients are based. Clients are selected according to relatively strict inclusion (degree of disability compatible with admission to a nursing home) and exclusion (e.g. behavioural problems) criteria. These systems usually function in parallel with the socio-health structures in place. Services are delivered by structures operated by the system or by external structures linked through contracts (hospitals, specialised medical care, long-term care institutions). An evaluation of these programmes in the USA [12] showed that they have an impact on the number and duration of short-term hospitalisations, the number of admissions to long-term institutions, drug use, mortality and the cost of services. However, this study did not include any specific control groups and the data from the PACE projects were only compared to national statistics for groups whose comparability is questionable. In Northern Italy, Barnabei et al. [13] showed with a randomised controlled trial that a programme of integrated social and medical care and case management is effective in reducing admission to institutions and functional decline in older people living in the community.

The Social HMO in the United States [14] and the SIPA (“Systàme de services intégrés pour personnes âgées en perte d'autonomie”) project in Montreal are also integrated services but do not include a Day Centre [15]. However, home care services are provided by personnel hired by or under contract with the organisation. All these fully integrated models are nested in the usual health and social services in a particular area but are run in parallel to them. They do not involve significant changes to the structure or processes of existing services, except for the negotiation of protocols for referring clients to ISD and the provision of some services not covered by ISD. Capitation budgeting is usually a key component of these programmes.

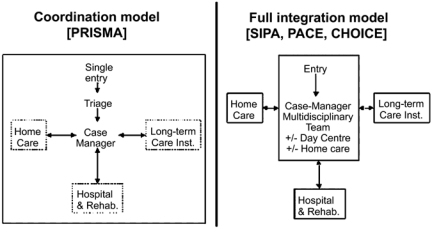

The other level of integrated care, co-ordination, involves the development and implementation of defined structures and mechanisms to manage the complex and evolving needs of patients in a co-ordinated fashion. Every organisation keeps its own structure but agrees to participate in an “umbrella” system and to adapt its operations and resources to the agreed requirements and processes. At this level, the ISD system is not only nested in the health care and social service system but is embedded within it. Figure 1 and Table 1 compare the co-ordination model with the full integration model.

Figure 1.

Comparison of two models of Integrated Service Delivery.

Table 1.

| Elements of Integrated Care | Co-ordination Model (e.g. PRISMA) | Full Integration Model (e.g. SIPA, PACE, CHOICE) |

|---|---|---|

| Link with the health care system | Embedded within | Nested in |

| Co-ordination | Essential at all levels (governance, management, clinical) | Essential for clinical work only |

| Case manager | Essential (works with existing teams in services) | Essential (with a multidisciplinary team) |

| Single entry | Essential | Not essential (referral procedure only) |

| Individualised service plan | Essential | Essential |

| Unique assessment tool | Essential for all partners and services | Essential for internal purposes only |

| Computerised clinical chart | Essential for all partners and services | For internal use only |

| Budgeting | Negotiation between partners (capitation not essential) | Capitation essential plus contract with external services |

Systems

(Continuous-lined boxes means that the organisations are fully independent in their structure and management; dotted-lined boxes means that part of the autonomy of the organisations is transferred to the integrated structure.) (Figure 1).

The PRISMA (Program of Research to Integrate the Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy) project in the Province of Quebec is an example of this type of integrated care [16]. This article will describe in more detail the integrated care mechanisms and tools developed and implemented by PRISMA. The mechanisms refer to (1) co-ordination between decision-makers and managers at the regional and local level, and the use of (2) a single entry point, (3) a case management process and (4) individualised service plans. The tools refer to (5) a single assessment instrument coupled with a management system based on the clients' functional autonomy, and (6) a computerised clinical chart for communicating between institutions and clinicians for client monitoring purposes. These tools not only facilitate the delivery of services adapted to the clients' needs but can also continuously monitor the resources and manage the supply of services effectively and efficiently. Since this model of co-ordinated system was developed to fit in a publicly funded health care system, capitation budgeting is not an essential component and funding of the system can be included as part of the agreement between organisations.

Description of the PRISMA model

Co-ordination between institutions is at the core of the PRISMA model. Co-ordination must be established at every level of the organisations. First, at the strategic level (governance), by creating a Joint Governing Board (“Table de concertation”) of all health care and social services organisations and community agencies where the decision-makers agree on the policies and orientations and what resources to allocate to the integrated system. Second, at the tactical level (management), a Service Co-ordination Committee, mandated by the Board and comprising public and community service representatives together with older people, monitors the service co-ordination mechanism and facilitates adaptation of the service continuum. Finally, at the operational level (clinical), a multidisciplinary team of practitioners surrounding the case manager evaluates clients' needs and delivers the required care.

The single entry point is the mechanism for accessing the services of all the health care institutions and community organisations in the area for the frail senior with complex needs. It is a unique gate which older people, family caregivers and professionals can access by telephone or written referral. A link is established with the Health Info Line available to the general population in Quebec seven days a week, 24 hours a day. Clients are referred to the ISD system after a brief needs assessment [triage] to ensure they meet the eligibility criteria for the integrated system (Table 2). Otherwise, they are referred to the relevant service. ISD eligible clients are then referred to a case manager. From previous work [17], we have developed a quick 7-question screening instrument (PRISMA-7) to be used by professionals and nonprofessionals to identify clients who should present moderate to severe functional decline and be eligible for ISD. This screening tool is used for triage either at the single-entry point or in volunteer agencies, and health and social services (emergency rooms, physicians' offices, home care services, etc.).

Table 2.

Admission criteria to an Integrated Service Delivery System

| • To be over 65 years ol |

| • To present moderate to severe disabilities (SMAF score ≥ out of 87) |

| • To show good potential for staying at home |

| • To need two of more health care or social services |

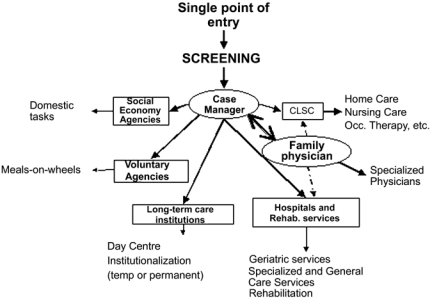

The case manager is responsible for doing a thorough evaluation of the client's needs, planning the required services, arranging to admit the client to these services, organising and co-ordinating support, directing the multidisciplinary team of practitioners involved in the case, and monitoring and re-evaluating the client. In a randomised trial, Eggert et al. [18] showed that case management is more effective, if the case manager is not just a service broker but is also actively and directly involved in delivering the services to the client in his/her area of expertise. The case manager should be legitimised to intervene in all institutions or services. Family physicians should be one of the case manager's primary collaborators because, in addition to being the main medical practitioner, they are pivotal in regard to access to and co-ordination of specialised medical services. On the other hand, the case manager relieves family physicians of some of their burden by facilitating access to and co-ordinating the rest of the social and health interventions. Figure 2 illustrates the case manager's place in the network.

Figure 2.

The PRISMA model of Integrated Service Delivery System.

The individualised service plan results from the overall assessment of the client and summarises the prescribed services and target objectives. It must be led by the case manager and established at a meeting of the multidisciplinary team including all the main practitioners involved in caring for the older person. In services or programmes where multidisciplinary meeting processes are already in place, the case manager joins this process without duplication. The individualised service plan includes the intervention plans of each of the practitioners and must be reviewed periodically.

The single assessment instrument is an essential element in this ISD model. It must allow for evaluating the needs of clients either at home or in institutions. The instrument must measure the clients' disabilities, resources and handicaps. The SMAF (Système de mesure de l'autonomie fonctionnelle—Functional Autonomy Measurement System) is a 29-item scale developed according to the WHO classification of disabilities [19]. It measures functional ability in five areas: activities of daily living (ADL) (7 items), mobility (6 items), communication (3 items), mental functions (5 items) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (8 items). For each item, the disability is scored on a 5-point scale: 0 (independent), −0.5 (with difficulty), −1 (needs supervision), −2 (needs help), −3 (dependent). The resources available to compensate for the disability are also evaluated and a handicap score is deducted. The stability of the resources is also assessed. A disability score (out of −87) can be calculated, together with subscores for each dimension. The SMAF must be administered by a health professional who scores the subject after obtaining the information either by questioning the subject and proxies, or by observing and even testing the subject. This instrument has been submitted to a number of validity and reliability studies [20, 21]. Correspondence of the SMAF score with the required nursing-care time and the cost of long-term care, either at home or in different institutional settings, has also been established [22].

A case-mix classification system based on the SMAF has also been developed [23, 24]. Fourteen ISO-SMAF profiles were generated using cluster analysis techniques in order to define groups that are homogeneous in regard to their profiles, but heterogeneous in other respects. These analyses were carried out with the data from a provincial study done by our team on nearly 2000 subjects living at home or in different types of residential facilities [22]. By linking the evaluation of the ISO-SMAF autonomy profile of an older person to the amount and cost of the resources that person requires, based on his/her living situation (community-living, institutionalised, etc.), it is a quick and easy task to monitor the clinical, administrative and research data. These profiles are used to establish the admission criteria to the different institutions and to calculate the required budget of the institutions, given the autonomy of their clientele [25]. In a health care system with multiple sources of funding, this system could be used as a basis for capitation budgeting.

In addition, implementation of an integrated system like this requires the deployment of a continuous information system and the use of computerised tools to facilitate communications and ensure the continuity of services. Through a computerised clinical chart (CCC), all the practitioners have quick access to complete, continuously updated information and can inform the other clinicians of the client's progress and changes in the intervention plan. The CCC is part of the management system and thus provides an interface between the clinical information and the management information. A CCC called the SIGG (“Système d'information géronto-gériatrique”) has been developed and implemented in a pilot project in Victoriaville (Quebec, Canada). This shareable, clinical chart is common to all the professionals in the service continuum for the older person. It uses the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services Internet network and Lotus Notes.

On-going studies on PRISMA model

The PRISMA group has implemented this model in two CLSC (“Centre local de services communautaires”) territories in the Victoriaville region (the Bois-Francs project). The purpose of this pilot project was to evaluate, using a quasi-experimental design, the implementation and impact of this model for community-living clienteles [26]. Two cohorts of subjects in the study (n=272) and control (n=210) areas were followed and evaluated annually over a three-year period (1997 to 2000). One of the main outcomes of the study, functional decline, was defined as either death, institutionalisation and significant increase in disabilities (difference of 5 points or more on the SMAF scale). In the study, there were fewer people who experienced a functional decline in the study group for those with moderate to severe disability at entry but not for the ones with mild disability. This effect was significant at 12 months (49.1% vs. 31.3 p=0.002) and tended to remain at 24 months (35.9 vs. 25.9 p=0.066). Desire to be institutionalised showed a significant decrease in the experimental group at 12 and 24 months. Caregivers' burden was significantly lower in the study group than in the control group at 12 and 24 months. Although the utilisation pattern of acute care hospitals was similar, the risk of returning to the emergency room within 10 days after a first visit or after discharge from an acute care hospital was significantly greater in the control group. The risk of being institutionalised tended to be greater in the control group (RR=1.44; p=0.06).

Based on these preliminary results, the group is now extending this model to CLSC territories in other regions in the Eastern Townships that present different environments: presence of multiple and university institutions, urban versus rural, presence or absence of an acute care hospital. The evaluation of the implementation focuses on the process of implementing the mechanisms and tools and how they function. The objective is to explain the variations observed between the different implementation settings using a case study approach developed by Yin [27]. The questions that are documented try to define the extent to which the clientele using the services corresponds to the clientele initially targeted; if the services delivered correspond to those planned; and if the delivery procedure corresponds to the one initially defined. Other questions focus on evaluating the process itself and identifying its strengths and weaknesses in order to reinforce or correct some of the elements comprising the new mechanisms and tools. The unit of analysis [case] is each of the selected CLSC territories involved in the study. The main variables and dimensions studied are: involvement of the decision-makers in the implementation; whether the main users have the same understanding of the mechanisms or tools; the population reached, productivity achieved, delays encountered, sources of references, time breakdown in relation to the mechanism functions, clinician-client interactions, problems identified, facilitating factors, etc. Data are collected from the policy-makers, managers, clinicians, as well as clients and informal care-givers using different methods (interviews, focus groups, surveys).

Effectiveness is being evaluated using a quasi-experimental design (pre-test, multiple post-tests with control group). As opposed to the Bois-Francs pilot project where efficacy was measured using service users as subjects, this study measures the effectiveness by selecting a sample of older individuals “at risk” of using the services. It employs a different sampling strategy from that used to recruit the users in the system. Although it requires a larger sample size, this strategy will enable us to measure the real populational effectiveness and to estimate the system penetration rate (accessibility). Using a list from the Quebec Health Insurance Board, a sample of people over 75 were selected and sent a postal questionnaire already developed and validated by our team [28]. The responses to this questionnaire or the fact of not returning it establish a risk of presenting a significant functional decline over the next year. Since the annual incidence of functional decline in this group is estimated to be 48% [28], it is probable that the great majority of subjects selected in this way will contact the socio-health network during the two years of the study. After being informed of the study and agreeing to participate, the subjects were evaluated at pretest (T0) and will be reassessed annually over a two-year period (T1, T2). The variables measured are: functional autonomy (SMAF), satisfaction in regard to the services received, client empowerment, caregivers' burden, utilisation of health services and social services, and drug use. An economic analysis is also being performed.

Conclusion

PRISMA is an innovative co-ordination type ISD model. Since it is embedded within the usual health care and social services system, this model could be more appropriate to the Canadian universal and publicly funded health care system than the fully integrated models tested so far. However, it requires a shift from the traditional institution-based approach to a client-centred approach and tremendous efforts in co-ordination at all levels of the organisations. The on-going studies will show if the model could be generalised to other areas with different characteristics and show data on its impact on clienteles and cost. Other studies are planned to focus on specific aspects of the model: an evaluation of the CCC to describe its perceived usefulness by the older people and the clinicians and its real use; a socio-political analysis of the different roles played by the provincial, regional and local levels to facilitate or constrain the implementation of integrated care; and the development of a conceptual framework to assess quality of health care and social services in an integrated care model.

The next step will be to test the model elsewhere in Canada and in other countries. In other health system contexts, the mechanisms and tools will probably have to be adapted. For example, in multi-payer systems, the management tool (ISO-SMAF profiles) could be used for funding or in the capitation payment calculation.

Finally, the PRISMA group is also a unique partnership experience between researchers, managers and policy-makers. Representatives of the managers and decision-makers form an integral part of the research team and are participating at every stage in the studies, i.e. developing the protocol, finding funding, conducting the studies and analysing and presenting the results. This exceptional partnership is possible because of the close links developed over the last few years between the researchers, managers and decision-makers. These productive experiences are proof of the value of the links between these different groups. In addition to periodical general meetings where all the projects are discussed, the researchers and managers are divided into mixed project teams to develop and conduct the various studies. Representatives of the managers and decision-makers and members of the research team also participate in discussions with the Regional Health and Social Services Boards involved in implementing the mechanisms and tools used in the research programme. Seminars and colloquia are organized to present and discuss the results of the studies or to review methodological questions. This partnership ensures the relevancy of the research projects and fosters the quick translation of research findings into better interventions, services and policies.

Contributor Information

Réjean Hébert, Institute of Aging, 1036 Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Québec, J1H 4C4, Canada.

Pierre J. Durand, Institute of Aging, 1036 Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Québec, J1H 4C4, Canada.

Nicole Dubuc, Institute of Aging, 1036 Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Québec, J1H 4C4, Canada.

André Tourigny, Institute of Aging, 1036 Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Québec, J1H 4C4, Canada.

The PRISMA Group, Institute of Aging, 1036 Belvédère Sud, Sherbrooke, Québec, J1H 4C4, Canada.

Vitae

PRISMA [Program of Research to Integrate the Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy] is a partnership between two research teams [Research Centre on Aging in Sherbrooke and Laval University Geriatric Research Team in Quebec City] and several health organisations in the Province of Quebec: Ministry of Health and Social Services, five Regional Health and Social Services Boards [Estrie, Mauricie-Centre-du-Québec, Laval, Montérégie, Quebec City], and the Sherbrooke Geriatric University Institute. PRISMA is funded by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec [FRSQ], and the partnering organisations. Many projects run by the PRISMA group are also funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.The PRISMA Group includes the following members:Réjean Hébert, MD MPhil; Nicole Dubuc, PhD; Dani;agele Blanchette, PhD; Gina Bravo, PhD; Martin Buteau, DSc; Johanne Desrosiers, OT PhD; Marie-France Dubois, PhD; Maxime Gagnon, MSc; Linda Millette, MD MSc[c]; Pascale Morin, RD PhD; Michel Raîche, MSc; Michel Tousignant, pht PhD; Anne Veil, MSW; Alain Villeneuve, DBA [Research Centre on Aging, Sherbrooke]; Pierre J. Durand, MD MSc; André Tourigny, MD MBA; Any Bussi;agere, MPs; Diane Morin, RN, PhD; Daniel Pelletier, MPs; Line Robichaud OT PhD; Louis Rochette, MSc; Mich;agele St-Pierre, PhD; Aline Vézina, PhD [Geriatric Research Team, Quebec City]; Louis Demers, PhD; Mich;agele Houpert, MSc[c]; Judith Lavoie, MSc [Télé-Université, Quebec City]; Pierre Bergeron, MD PhD; Philippe De Wals, MD PhD [National Public Health Institute, Quebec]; Anne Lemay, PhD [CHUM/Montreal University Health Centre, Montreal]; Lysette Trahan, PhD [Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services]; Mich;agele Paradis, MSc [Quebec Regional Board]; Linda Dieleman [Estrie Regional Board]; Irma Clapperton; Jocelyn Lavallée; Éliane Lafleur, MBA [Laval Regional Board]; Line Beauchesne, MSc; Lucie Bonin, MD MSc; Danièle Laurin, PhD; Hélaine-Annie Roy, MSW; [Mauricie-Centre-du-Québec Regional Board]; Hung Nguyen [Montérégie Regional Board].

References

- 1.Hébert R. Functional decline in old age. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997;157(8):1037–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolduc M, Trahan L. Direction de l'évaluation. Québec: MSSS; 1988. Programme d'évaluation portant sur le processus de réponse aux besoins de longue durée des personnes âgées ayant des limitations fonctionnelles. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trahan L. Service de l'évaluation, rédaptation et services de longue durée. Québec: MSSS; 1989. Les facteurs associés à l'orientation des personnes âgées dans des établissements d'hébergement: une revue de littérature. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman H, Beland F, Lebel P, Contandriopoulos AP, Tousignant P, Brunelle Y, et al. Care for Canada's frail elderly population—fragmentation or integrations. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997;157(8):1116–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollander MJ, Walker ER. Division of Aging and Seniors. Health Canada: Ottawa; 1998. Report of continuing care organization and terminology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starfield B. Primary care—concept, evaluation, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kodner DL, Kyriacou CK. Fully integrated care for frail elderly: two American models. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2000;1(1):1–24. doi: 10.5334/ijic.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yordi CL, Waldman J. A consolidated model of long-term care: service utilization and cost impacts. Gerontologist. 1985;25(4):389–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/25.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branch LG, Coulam RF, Zimmerman YA. The PACE evaluation: Initial findings. Gerontologist. 1995;35(3):349–59. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinnell Beaulne Associates Ltd. CHOICE Evaluation project. Evaluation summary. Final report; 1998 November 26.

- 12.Eng C, Pedulla J, Eleazer P, McCann R, Fox N. Program of all-inclusive care for the elderly [PACE]: an innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1997;45:223–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnabei R, Landi F, Gambassi G, Sgadari A, Zuccala G, Mor V, et al. Randomised trial of impact of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(141):1348–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leutz W, Greenberg R, Abrahams R, Prottas J, Diamond LM, Gruenberg L. Changing health care for an aging society: planning for the social health maintenance organization. Lexington, Mass: Lexington Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergman H, Béland F, Lebel P, Leibovich E, Contandriopoulos AP, Brunelle Y, et al. L'ĥpital et le système de services intégrés pour personnes âgées en perte d'autonomie [SIPA] [Hospital and integrated services delivery network for the frail elderly]. Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé. 1997;4(2):311–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hébert R. Les réseaux intégrés de services aux personnes âgées: une solution prometteuse aux problèmes de continuité des services. [Integrated services for older people: a promising solution to the problems of continuity of services]. Médecin du Québec. 2001;36(8):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hébert R, Spiegelhalter DJ, Brayne C. Setting the minimal metrically detectable change on disability rating scales. 1997;78:1305–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eggert GM, Zimmer JG, Hall WJ, Friedman B. Case management: a randomized controlled study comparing a neighborhood team and a centralized individual model. Health Services Research. 1991;26(4):471–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hébert R, Guilbault J, Desrosiers J, Dubuc N. The functional autonomy measurement system [SMAF]: a clinical-based instrument for measuring disabilities and handicaps in older people. Geriatrics Today. 2001 Sep;:141–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hébert R, Carrier R, Bilodeau A. The functional autonomy measurement system [SMAF]: description and validation of an instrument for the measurement of handicaps. Age Ageing. 1988;17:293–302. doi: 10.1093/ageing/17.5.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Hébert R, Dubuc N. Reliability of the revised functional autonomy measurement system [SMAF] for epidemiological research. Age Ageing. 1995;24(5):402–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hébert R, Dubuc N, Buteau M, Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Trottier L, et al. Resources and costs associated with disabilities of elderly people living at home and in institutions. Canadian Journal On Aging—Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement. 2001;20(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubuc N, Hébert R, Desrosiers J, Buteau M, Trottier L. Système de classification basé sur le profil d'autonomie fonctionnelle. In: Hébert R, Kouri K, editors. Autonomie et vieillissement. St-Hyacinthe: Edisem; 1999. pp. 255–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubuc N, Hébert H, Desrosiers J, Buteau M. Disability-based casemix for elderly people in integrated care services. Submitted.

- 25.Tousignant M, Hébert R, Dubuc N, Simoneau F, Dieleman L. Application of a case-mix classification based on the functional autonomy of the residents for funding long term care facilities. Age and Ageing. 2003;32:60–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durand PJ, Tourigny A, Bonin L, Paradis M, Lemay A, Bergeron P. Mécanisme de coordination des services géronto-gériatriques des Bois-Francs. Health Transition Fund. Health Canada; April 2001 Research Report QC–403.

- 27.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Applied social research methods series. Vol. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hébert R, Bravo G, Korner-Bitensky N, Voyer L. Predictive validity of a postal questionnaire for screening community dwelling elderly individuals at risk for functional decline. Age Ageing. 1996;25:159–67. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]