Abstract

By the introduction of a public, mandatory program of Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) on April 1, 2000, Japan has moved towards a system of social care for the frail and elderly. The program covers care that is both home-based and institutional. Fifty percent of the insurance is financed from the general tax and the other fifty percent from the premiums of the insured.

The eligibility process begins with the individual or his/her family applying to the insurer (usually municipal government). A two-step assessment process to determine the limit of benefit follows this. The first step is an on-site assessment using a standardised questionnaire comprising 85 items. These items are analysed by an official computer program in order to determine either the applicant's eligibility or not. If the applicant is eligible it determines which of 6 levels of dependency is applicable.

The Japanese LTCI scheme has thus formalised the care management process. A care manager is entrusted with the entire responsibility of planning all care and services for individual clients.

The introduction of LTCI is introducing two fundamental structural changes in the Japanese health system; the development of an Integrated Delivery System (IDS) and greater informatisation of the health system.

Keywords: elderly, Japan, long term care, health care financing, care insurance, health care innovation

Introduction

Japan implemented a new social insurance scheme for the frail and elderly, Long-Term-Care Insurance (LTCI) on 1 April 2000. It is an époque-making event for the history of the Japanese public health policy, because it means that Japan has moved toward socialisation of care in modifying its tradition of family care for the elderly. Like the Adel reform in Sweden [1], one of the main ideas behind the establishment of LTCI was to “de-medicalise” and rationalise the care of elderly persons with disabilities that were characteristic of the process of ageing. Because of the ageing of the society, the Japanese social insurance system requires a fundamental reform. The introduction of LTCI is the first step in the future health reform in Japan. The LTCI scheme requires each citizen to take more responsibility for finance and decision making in the social security system. As explained later, the following are key concepts of the LTCI scheme; self-determination and self-reliance, eligibility assessment, care management, consumerism, integration of services, and contract.

In this article, we explain the background factors of establishment of the LTCI scheme, its detail and on-going structural change in the Japanese health system. Especially, we focus on the development of Integrated Delivery System (IDS) in Japan.

Background

It is important to understand the background factors of this paradigm shift in health care. The first factor is the rapid greying of the Japanese society. In 1970, the population of 65+ was 7% of the total, and after only 25 years, in 1994, it had doubled to become 14%. If we compare this period from 7 to 14% with other countries, France required 125 years and the USA 75 years. Furthermore, according to the official demographic estimation, the proportion of the aged will continue to increase to reach 25.8% in 2025. This fact means that Japan has to prepare for a highly aged society in a very short period in a difficult economic situation. The second factor is both demographic and sociological. With fewer children (Total Fertility Rate is 1.3 in 1998), more women working, and changing attitude toward family responsibilities, the traditional system of informal care-giving is widely perceived as inadequate to take care of the increasing number of the frail elderly. In fact, about 40% of the households with elderly people are now so-called “aged households”, that is, single old person's household or old couple's household. This situation naturally requires the socialisation of care. The third factor is a financial crisis of the social security fund. In 1997, the total medical expenditure of Japan was 27 trillion yen, of which 60% was consumed by hospital services. About 46% of the hospital patients are 65+, and 43% of the elderly patients stay in hospital for more than 6 months. One of the reasons for this long period of stay in hospital is the shortage of skilled nursing facilities and home care services. The average health expenditure per capita of the elderly is about 5 times more than that of the young generation. Furthermore, it is estimated that the Japanese public pension system that adopts the pension benefit imposition system will be in crisis in the near future because of the maturation of the scheme. It is said that the introduction of LTCI is the first and important step of a radical reform of the social security system in Japan.

The Japanese system

Medical insurance scheme in Japan

Japan's universal health insurance system

Japan's universal health insurance system, which covers the country's 122 million population, is segmented according to workplace and living place. The type of company one works for determines the insurance society to which one belongs and the financial contributions one must make. Although thousands of independent societies therefore exist, they are all integrated into the uniform framework mandated by the national government. The Japanese health financing system for all societies is based upon fee-for-service reimbursement under a uniform national price schedule. Various health insurance funds, both public and semi-public, gather the premium from their insured and reimburse the cost for the medical facilities according to the type and volume of provided services. The health insurance scheme is categorised into three basic groups according to age and employment status; Employee's Medical Insurance scheme (EMI) for employers and their dependants, National Health Insurance scheme (NHI) for self-employed, farmers, retired and their dependent and a special pooling fund for the elderly. All Japanese are covered by at least one of these schemes. Because the Japanese system is portable, Japanese residents can receive medical services at any medical facilities with a modest co-payment.

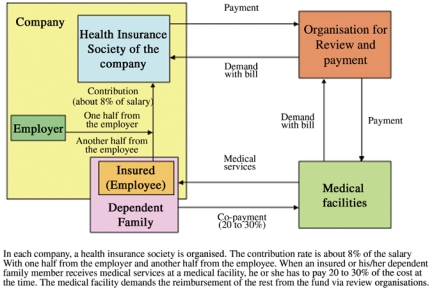

Figure 1 shows the EMI scheme. Each enterprise organises its health insurance fund. The contribution rate is about 8% of the salary and generally one half comes from the employee and the rest from the employer. In the case of a small company, the health insurance fund is substituted by a governmental organisation (the Seikan-Kenpo). When an insured person receives medical services in a medical facility, he has to pay part of the cost at that time; 20% for outpatient services, and 30% for in-patient services. Each medical facility demands the reimbursement of the rest from the fund. In order to prevent an unfair demand for reimbursement, a reviewer organisation in each prefecture can intervene between the medical facilities and funds.

Figure 1.

Structure of Employees Medical Insurance Scheme

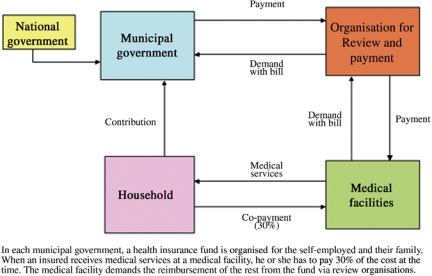

Figure 2 shows the NHI scheme. The NHI is a scheme for the self-employed and his family including farmer and retired. Each municipality (or their association) organises its NHI fund and gathers a premium from the insured. The formula of calculation of the premium is different among the funds to some extent, but basically based on the income, the number of family members, and the amounts of other wealth (i.e. land) of each household. The relationship among patients, medical facilities, and the fund is the same as that of EMI except for the amount of co-payment (30% both for out- and in-patient services).

Figure 2.

Structure of National Health Insurance Scheme

Before 1982, there were only the EMI and the NHI schemes. The EMI scheme is applicable only to employees and their family members; therefore the retired automatically join the NHI scheme. It is quite natural that the elderly need more medical services although their income becomes less than before. As a result, the government is obliged to financially support the NHI to an enormous extent, resulting in an immense deficit. To cope with this situation, the government promulgated the Health Service Law for the Elderly in which a special medical insurance scheme for the aged was created.

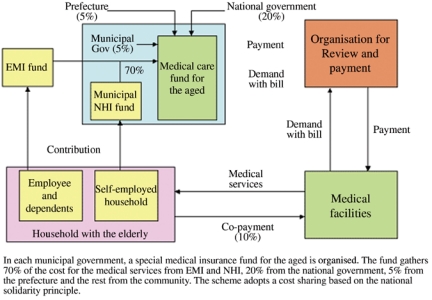

Figure 3 shows the scheme for the elderly. The most important point is that the cost sharing between EMI and NHI was introduced under the principle of national solidarity in order to stabilise the financial basis of the fund. The fund created in each municipality receives 70% of the cost from EMI and NHI according to the established calculation formula, 20% from the national government, 5% from the prefecture and the rest from the local municipality. Another important characteristic of the scheme is its co-payment rule. For the co-payment of the user, an elderly patient is required to pay 10% of total cost.

Figure 3.

Structure of medical care under the Health Service Law for the aged

The official fee schedule

Under the Japanese universal health insurance system, all medical facilities are reimbursed for medical services according to the official fee schedule. There is a separate reimbursement schedule for pharmaceuticals (see below). The fee schedule is a very detailed form of pricing control, listing more than 3000 medical procedures for physicians alone. The fee schedule is revised every two years. There are two different stages of fee schedule revision: (1) setting total medical expenditures and determining the distribution of funds to different groups (physicians, dentists, pharmacists, etc.) and (2) after determining the share for each of the players, modifying the fees for the 3000 procedures. Although the Japanese health system is based upon the fee-for-service system, it can be considered a kind of global budget system with a very tight bureaucratic pricing control. In the case of geriatric wards, payment is based on per diem.

The official schedule for pharmaceutics

The price schedule for pharmaceutics lists more than 13,000 drugs by brand name. The schedule is revised every two years according to the investigation of the market price of each drug. The general principle used to determine the new price of each drug is as follows: new price=the weighted average in the actual market prices+2% of margins (see Box 1).

Box 1. The Japanese administration system.

The Japanese administration system comprises three levels; central government, 47 prefectures, and 3300 municipalities. Central government establishes the principles and basic laws. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has responsibility for the health policy. National health policy is materialised through local governments; prefecture and municipality. Most of the basic health and welfare services, such as for mother and child, the elderly, and the handicapped, are provided under the responsibility of the municipality. The prefecture co-ordinates activities among the different municipalities and provides direct health services for specific problems, such as tuberculosis, AIDS, and the mentally handicapped. Each of the three levels of government has its assembly and chief. For the local governments, inhabitants directly elect both. In the case of central government, the citizens directly elect the members of the Diet, but the Diet members elect the Prime Minister.

The former welfare service for the aged

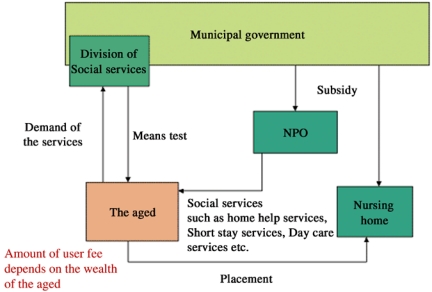

Figure 4 shows the former welfare system for the elderly before April 2000. If a frail elderly person wanted to receive welfare services, at first he or she had to apply to the local government (municipal welfare office). After a means test, the local government determined the eligibility and the amount of user fee. If the applied person was evaluated as eligible, he or she could receive welfare services as a kind of placement. Available services were home care services (i.e. home help services, home bathing service, day care health service, short stay service, catering service, lease of home care and rehabilitation equipment) and institutional service in a nursing home. The amount of user fee was depending on the economic status of the applicant family. As the user fee was more expensive than that of medical services for the middle and upper class households, most of them preferred institutionalisation in hospitals as a substitute to a nursing home. This kind of hospitalisation with a social reason is cheap for the user but expensive for the insurer and the government. One of the reasons for the establishment of LTCI was to solve this problem that was criticised by the payer organisations as a symbol of the inappropriateness and inefficiency of the Japanese health and welfare system for the aged.

Figure 4.

The former system of welfare services for the aged in Japan

The LTCI scheme [2]

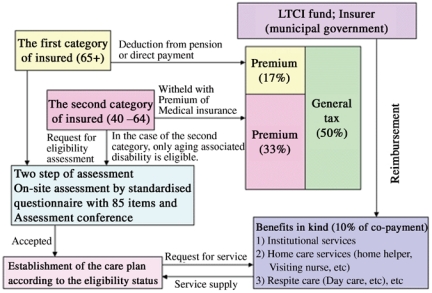

Figure 5 describes the LTCI scheme. The new system is different from the former placement system in various points, such as financing method, eligibility requirement, co-payment, etc.

Figure 5.

System of Long-Term-Care Insurance in Japan

Financing system

The budget of the insurance is based on fifty percent from the general tax and another fifty percent from the premium of the insured. There are two types of insured; the first category of insured who are 65+, and the second category of insured that is between the age of 40 and 64. The first category of insured is asked to pay a premium deducted from pension or direct payment for insurer according to their pension status. In the case of the second category of insured, his or her premium is withheld from the medical insurance premium. The average premium for the year 2000 is about 3000 yen (25 US$; 1US$=120 yen) per month.

Eligibility

The benefit includes social welfare services such as home help and bathing service, stay in nursing home, as well as the use of medical services such as visiting nurses and institutional care in long term care hospitals. There is a difference in eligibility requirements between the first and the second category of insured. For the former there is no requirement related to the causes of dependency, but for the second, the eligibility is limited only for the 15 ageing-type disabilities (e.g. Alzheimer's disease, stroke, etc). The eligibility process begins with the individual or his/her family applying to the insurer (usually municipal government). A two-step assessment process follows and determines the limit of benefit. The first step is on-site assessment using the 85 items of a standardised questionnaire, each with a choice of three or four levels, plus space for comments on any particular aspects to be remarked on. The 85 items are analysed by an official computer program to classify the applicant into one of 6 levels of dependency or to reject eligibility. The lightest level is “assistance required” which is subject to preventive services; the other five levels are called “care required”. The second step is the assessment conference by health care professionals. The conference reviews the classification made by a computer program by taking into account the descriptive statement plus a report from the applicant's home doctor. The eligibility decision is then communicated to the applicant within 30 days of applying. If dissatisfied, the applicant may appeal to an agency of re-evaluation at the prefecture level.

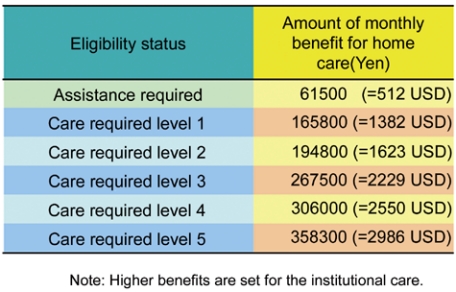

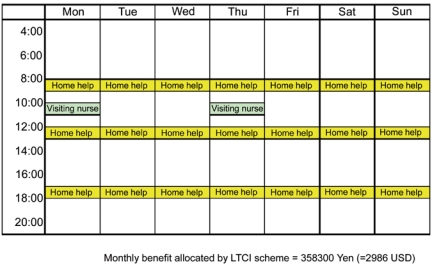

Each eligibility level entitles the applicant to an explicitly defined monetary amount of services. Table 1 shows the amount of benefit for home care. In the case of institutional care, about 1.4 times higher amounts are set for each level. The recipient has to pay 10% of the cost as co-payment. Theoretically, users are free to choose services, but in reality, the care-manager who constitutes a care plan, a weekly time schedule of services, intervenes in this process and co-ordinates the services for the applicant. Table 2 shows an example of a weekly care plan for the user of care required level 5. To be a care-manager, it is required to pass the official examination and to receive a brief training.

Table 1.

Table 2.

The services covered by the LTCI scheme are as follows;

Home care: home help services, visiting nurse services, visiting bathing service, visiting rehabilitation services, etc

Respite care: day care services, medical day care services, short stay services

Institutional care: nursing home, health service facility for the aged (rehabilitation facility), and geriatric ward under the LTCI scheme

It should be noted that institutional care in the health service facility for the aged and geriatric ward (only facilities under the LTCI scheme), and medical day care services, visiting nurse services, and visiting rehabilitation services are included in the LTCI scheme. These services were formerly covered by the medical insurance scheme. This removal of medical services from the health insurance scheme is expected to reduce the medical expenditure to some extent. However, some researchers predict this reduction will not occur [3], and in fact, this reduction in total health expenditures for the aged has not been observed up to now.

Care management – the heart of integrated care

In policies concerning integrated care for the disabled elderly, care management has become an important topic for consideration. Standardised care, continuity of care, flexibility of care, and finely tuned co-ordination between the different kinds of care providers are a central part of care management in order to realise high quality care for the disabled aged and to enable them to continue to live independently in their own homes for as long as possible. This is the most important reason that the Japanese LTCI scheme has formalised the care management process. A care manager is entrusted with the entire responsibility of planning all care and services for individual clients. According to the results of a needs assessment of the client and his or her wish, a care plan is drawn up. The care manager organises the care specified in the care plan and works with the client, supervises and evaluates the care process (monitoring). When necessary, the care plan is adjusted. In this way the care manager plays a pivotal role in the LTCI scheme. The LTCI scheme pays a fee of care management for each care manager (6500–8400 Yen per month per each case: =54–70 US$; 1 US$=120 Yen).

The introduction of LTCI has changed the balance of authority in the health care market. Traditionally physicians have always played a key role in the authority and have influenced the care process of the frail elderly. However, the introduction of LTCI has changed the balance of authority from the physician to the care manager. This shift in authority requires skill in conflict management for each care manager, because he or she is often confronted with the problem of co-ordination among different care providers who do not always believe the authority and ability of care manager.

Although the role of care manager is pivotal in the LTCI scheme, there are lots of problems concerning the level of ability among them. Most of the care managers are newcomers who do not always have enough knowledge, skill and experience for appropriate care management. Recently we did a field research on the actual situation of care managers in Fukuoka prefecture [4]. The results are as follows: of 76 care manager offices, about half of them did not draw up any care plan. Of the 4000 care plans drawn up, 40% were established by only four care management offices. To improve the level of their knowledge and skill is the most important issue for the LTCI scheme. Actually we organise several re-training courses and some study groups where care managers can exchange their knowledge and experience in order to ameliorate their ability (see Box 2).

Box 2. An example of a training seminar for the care managers.

On 23 and 24 February 2001, we organised a training seminar for the care managers in Fukuoka prefecture. Seventy-one care managers participated in the seminar. In this seminar, the story of one dementia case was used. The setting was as follows: A female dementia case. 83 years old. Living alone. Her son lives in the neighbourhood. A slight paraplegia. Contraction of a knee joint due to rheumatoid arthritis. Severe dementia. A home visiting nurse played the role of the dementia woman. The experienced care manager played the process of care management. Participants were separated into seven groups and within each group they were required to simulate the process of the care management: assessment, reduction of care plan, monitoring and re-evaluation. At each stage of the process, all groups were required to present their results and to discuss with other groups. At the end of the seminar, the tutors evaluated their performance.

Structural change in health sector after the introduction of LTCI

After the LTCI, two fundamental structural changes are on going in the Japanese health system; development of Integrated Delivery System (IDS) and informatisation of health system. According to Leuz [5], there are three levels of integration: (1) linkage; (2) co-ordination; and (3) full integration. Kodner and Kyriacou describe these models as follows [6]:

Linkage

In this organisational model, closest to usual care arrangements, providers serving the general population seek outside assistance for the frail elderly and other patients with complex needs, on an ad hoc or systematic basis, from caregivers with special know-how and complementary services. However, the parties involved at this level of integrated care continue to function within their respective jurisdictions, eligibility criteria, funding constraints, service responsibilities, and operational rules;

Co-ordination

Integrated care at this level focuses specifically on patients, like the frail elderly, who are receiving health and social care services on a short- or long-term basis, either in conjunction with one another or sequentially. The organisational response at the core of this model is the development and implementation of defined structures and mechanisms to alleviate confusion, poor communication, fragmentation and discontinuity within and between sectors and systems, and to promote information-sharing. The emphasis is on creating an infrastructure to manage the full spectrum of care and services for the target group. Programs such as this may receive assistance with funding from governmental and/or non-governmental organisations. Co-ordination techniques include comprehensive assessment procedures, care management, joint care planning and team care, disease management (e.g. standardised guidelines and protocols), and common clinical records; and,

Integration

At this, the level of most far-reaching and potentially most powerful change, new, comprehensive programs are created to address the needs of medically and socially complex groups, by combining responsibilities, resources and financing from multiple systems under one organisational roof. Thus, funding streams and services are bundled together and globally managed by a unified service network using similar mechanisms and techniques found in the co-ordinated models above. This network can operate either under common ownership and control, or “virtually” through contractual relationships.

The typical case of full-integration is the American integrated delivery systems (IDSs) that are vertically integrated entities; they comprise a network of insurers, health maintenance organisations (HMOs), hospitals, physicians practices, and other entities that provide medical and social care for a defined population [7]. The four key components of an IDS are thus one or more hospitals, sub-acute care facilities, and physicians practices, in addition to a managed care plan or HMO. The first three provide the care; the last pays for it. As Japan adopts the universal health insurance system, there is no HMO type insurer. Therefore, the true type of IDSs does not exist in Japan, and only co-ordination types of integrated care entities are possible. In this article, we define this type of integrated care facilities as the IDS (Integrated Delivery System), in order to avoid the confusion.

The past decade has witnessed considerable growth in the development of IDSs in the Japanese health care sector. They provide a wide range of services from acute health care to long-term care including intramural and extramural care for the aged. Because the Japanese tariff schedule for the acute care hospital adopts “the-length-of-stay dependent sliding scale”, the acute care facility receives a reduced payment for the patients over critical length of stay. Therefore, it is very important for the management of the acute care facility to have the long-term care services receive the patients after the acute phase of care. At the first stage of the development of IDS in Japan, many private acute care hospitals constructed or bought the long term care facilities in order to ameliorate managerial efficiency. Furthermore, as the Japanese government has been trying to develop home care services as a substitute of institutional care services during the past decade, these facilities have developed extramural health services, such as visiting nursing services, visiting rehabilitation, day care services, short stay services, and so on. The government has offered several financial incentives in order to develop the home care services, such as low interest loan, subsidies, and relatively higher tariff schedule.

After the introduction of LTCI, many social and health care organisations have been entering into the market. Most of them are mono-service providers, such as home help services and visiting nurse services, and they are competing with the existing IDSs. Under the LTCI scheme, the drawing-up of a care plan is required, and within the care plan, various types of services should be organised according to the needs and demands of users. Compared with mono-service organisation, the IDSs are conducting this co-ordination task more easily, because they have several kinds of health and social services in their own organisation. Especially to be equipped with intramural services is an important merit for them, because the frail elderly and their family always fear an emergency situation. From the viewpoint of ability and experience of care managers for the service co-ordination, the IDSs are much more advanced. As a result, IDSs draw up most of the care plans in the region; our field research showed that 40% of care plans were established by only four of 70 care management offices in a region, and that all of four offices belonged to IDSs.

The users, on the other hand, welcome the development of IDS, because this type of organisation offers one-stop services for the client. In fact, our past research showed higher levels of satisfaction among the IDS users [4, 8].

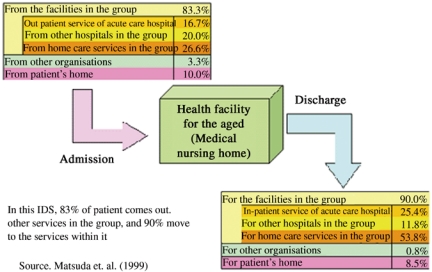

Figure 6 shows the flow of users in an IDS that we investigated [9]. The eighty-three percent of users came from the facilities in the same group and 90% discharged to the services of the group. According to the results of our previous investigation, the degree of monopolisation is very high among other Japanese IDSs as in this case [9, 10].

Figure 6.

An example of users' flow in a vertical IDS in Japan

A good information system is also important to the development of integrated care [11]. The LTCI scheme will facilitate informatisation of the Japanese health system because the scheme requires in principle tele-transmission of bills from service providers to the insurers. In fact, about 50% of providers under the LTCI scheme realise the informatisation of the system at the end of 2000. A number of private companies are competing for the development of software which integrates needs assessment, care management, reimbursement procedure, internal resource management, and so on (see Box 3).

Box 3. An example of the IDS in Japan.

K rehabilitation hospital has its origin in a psychiatric hospital (47 beds) established in 1962. This private institution has been a leading entrepreneurship hospital in Japan. In responding to the greying of society, they changed their function from psychiatric care to long-term care and rehabilitation care in 1982 (130 beds, now 198 beds). In 1983, they opened the first day care centre in order to support the disabled aged and their families. In 1987, they constructed a health facility for the aged (150 beds) that was the first model facility supported by the Ministry of Health. This facility is a halfway institution for the disabled elderly who want to return to their home. The main function is rehabilitation care, and in order to fulfil this function, they have organised a series of home care services; visiting nursing services, home help services, visiting rehabilitation services, visiting bathing services, catering services, and counselling and care management services. Also, they organise a volunteer group that is working for the disabled aged in the community (i.e. support of catering services and transporting). Now K hospital becomes a very important infrastructure for the health policy of K city.

Evaluation of LTCI scheme by users

How do the users evaluate the LTCI scheme? Although it is too early to discuss this matter, we would like to present some study results about this point. According to the official data on the change in volume of home care services after the introduction of LTCI [12], among the investigated 1263 users, an increase in service volume was observed for 67.5% of them. On the contrary, a decrease in service volume was observed only for 17.7%. Our field study on consumer's satisfaction for home care services in Fukuoka prefecture (sample size=344 home care service users under the LTCI) [4] also shows similar results. According to our results, about eighty percent of the users replied that they were satisfied with the LTCI scheme and forty percent of them indicated the improvement of accessibility for services as one of the positive effects after the introduction of LTCI. As the LTCI scheme permits home care services delivered by for-profit private organisations, that was not allowed under the past welfare scheme, the improvement in accessibility of services has been realised through an increase in the number of private organisations. For example, the number of home help service providers has increased from 9185 to 13,349 between April and December 2000 throughout the country [12]. We also conducted the questionnaire survey on the quality assurance activity for the service providers in Fukuoka prefecture (sample size=215) [4]. The results show that ninety-three percent of them organise some activities for quality assurance and risk management. Considering the results of preliminary studies for the evaluation of the LTCI scheme up to now, it could be concluded that the introduction of the LTCI scheme was relatively good and that the users generally approve the scheme.

The financial effects of LTCI

One of the main objectives of the introduction of LTCI is to reduce the financial burden of the social security fund. However, the most recent result showed that the reduction due to LTCI was very limited and that the total of health expenditures for the aged has increased by 0.30% more than expected [13]. Increase in use of institutional care is one of the main factors for this increase. Before the introduction of LTCI, the access to nursing homes was strictly limited by the placement system. Formerly, as users had to pay users' fee according to the income-dependent sliding scale, users belonging to the middle and upper class had to pay almost all of the total cost. The introduction of LTCI has opened the door of nursing homes for all possible users regardless of their economic and social situation with 10% of co-payment. Now, the waiting list for institutional care under the LTCI scheme has become very long. The cost of institutional care is about 1.4 times more than home care, i.e. in the case of care required level 1, the amount of monthly benefit is about 225,000 yen (1875 US$) for a user in a nursing home, and 165,800 yen (1382 US$) for a user of home care. Therefore, an increase in the use of institutional care means an increase of the financial burden of the insurer. Thus, it is an urgent task for the government to develop high quality home care services and to facilitate the substitution from institutional to home care. Volume control at the local level, differentiation of user's fee (higher co-payment for the institutional care), the introduction of cash allowance for home care service users will be possible solutions for limiting the volume of institutional services.

Conclusion

Along with the rapid greying of the society and because of economic stagnation, the Japanese government is trying to restructure the health system. The introduction of the LTCI scheme is the first step in the health system reform of Japan. As one of the main purposes of the introduction of LTCI is to de-medicalise the care for the disabled aged, it means that volume of aged clients in the medical market will decrease in future. It is said that there are too many acute care beds in Japan and that two thirds of them (about 600,000 beds) are unnecessary. This situation requires medical facilities to re-consider their managerial strategy. Recently, the fee schedule for hospitals was re-arranged in order to facilitate the restructuring of the health system. In the new fee schedule, the function of each hospital is taken into consideration. For example, the average length of stay is one of the criteria. The longer the average length of stay, the smaller the profit each hospital can expect in the current system. Using a financial incentive by tariff schedule, the government has tried to reduce the number of acute care beds. As about 70% of the private acute care hospitals are suffering from the deficit, this program is very effective. In order to survive under this difficult situation, most small and medium size private hospitals are obliged to decide their future directions. One possibility is downsizing and specialisation such as in surgery, orthopaedics, ORL, and ophthalmology. Another possibility is to become a long-term care facility that requires less human resources. In order to obtain enough clients, most of the long-term care facilities are trying to expand their activity from intramural to extramural medical and social services. In short, they have chosen to become IDSs. According to the results of the first large study on the Japanese Integrated Delivery System by Niki [14], about half of the IDSs are organised on the basis of small size hospitals. The financial aspect of these IDSs is generally good. According to our three in-depth case studies of IDSs in Japan, by reducing the average length of stay in the core-acute care hospital, the IDSs made a profit both from the acute and chronic care sectors. Especially the average profit rate of long term care facilities was very high; about 15%. Considering this situation, Niki concluded that the IDSs would be winners in the future health care market in Japan [14].

Furthermore, some IDSs are now managing the assisted living facilities designed for the disabled aged. The outpatient divisions of the core-hospital or affiliated clinics are functioning as home doctors for the clients and at the same time as an entrance of the IDS. This type of IDS is highly appreciated by users because they offer assurance and safety for them with a reasonable cost. In conclusion, as Niki pointed out [14], the IDS will become a very important social infrastructure for the future aged society in Japan.

Appendix

Contributor Information

Shinya Matsuda, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health Iseigaoka 1-1, Yhatanishi, Kitakyushu 807-8555, Japan.

Mieko Yamamoto, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health.

References

- 1.Andersson G, Karlberg I. Integrated care for the elderly. The background and effects of the reform of Swedish care of the elderly. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2000 Nov 1;1 Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuda S, Okochi J, Takahashi T, Takamuku K. Problems regarding the patient classification system in the long term care insurance of the aged in Japan. Casemix Quarterly. 2001;3(1):15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikegami N. Public long-term care insurance in Japan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(16):1310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuda S, et al. Report on LTCI services in Onga region, Fukuoka Prefecture. Onga Health Center. Fukuoka; 2001. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lesson from the United States and United Kingdom. The Milbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodner DL, Kyriacou CK. Fully integrated care for frail elderly: Two American models. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2000 Nov 1;1 doi: 10.5334/ijic.11. Available from: URL: http://www.ijic.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young DW, McCarthy SM. Managing integrated delivery systems. Washington: AUPHA Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda S, et al. The report on integrated delivery system. Tokyo: Saiseikai; 1999. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda S, et al. The first report on integrated delivery system in Japan. Tokyo: Institute for Health Economics and Policy; 1999. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda S, et al. The second report on integrated delivery system in Japan. Tokyo: Institute for Health Economics and Policy; 2000. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA. Remaking health care in America – building organized delivery systems. Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 2000.

- 13.Shakai Hoken Junpo (A ten days report on social security) 2001;No. 2004:32–33. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niki R. Hoken-Iryo-Fukusi Fukugotai (Integrated Delivery System) Tokyo: Igaku shoin; 1998. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]