Abstract

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS), first described in 1955, is a rare clinical syndrome of unknown etiology. CCS is diagnosed clinically, and the presenting symptoms include alopecia, cutaneous hyperpigmentation, gastrointestinal polyposis, and onychodystrophy, often accompanied by diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain. We describe a unique case of CCS that presented with eosinophilic infiltrate on gastric and duodenal biopsies and review the literature pertaining to this rare syndrome.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare nonfamilial disease that has been reported to a very limited extent. First described in 1955, the primary features of the disease include alopecia, cutaneous hyperpigmentation, characteristic intestinal polyposis, and onychodystrophy (1). Other clinical manifestations include diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain. The etiology of CCS is unknown, and no medical therapy has been shown to be consistently effective (2). The overall prognosis for CCS is poor, and its course is characterized by progressive disease with spontaneous remissions and frequent relapses (3–5).

The gastrointestinal polyps found in CCS are retention-type or hamartomatous in nature and are not neoplastic pathologically (6). Classic findings include a myxoid expansion of the lamina propria, and increased eosinophils may be seen in the polyps (3). We report on a patient with CCS who initially presented with nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and an eosinophilic infiltrate on biopsy in the context of the full CCS phenotype.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted to the Baylor University Medical Center emergency department in November 2004 complaining of a 6-month history of cramping and midepigastric pain that had progressively worsened 2 weeks prior to presentation. The pain was continuous but was exacerbated with eating. These symptoms were accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and occasional hematemesis. In addition, she reported two to three loose stools per day. Her past medical history included hypertension, hypothyroidism, and an episode of Lyme disease. Past surgical history was significant only for prior tonsillectomy and appendectomy. She was a nonsmoker and nondrinker. Her mother had had irritable bowel syndrome, and two children had an ill-defined immunodeficiency syndrome, which was also present in the father of the children. She showed no signs of cancer.

An abdominal sonogram was done, which revealed cholelithiasis and evidence of cholecystitis, for which she underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intraoperative cholangiography done at the time of surgery demonstrated a tapering of the common bile duct, which was suspicious for a retained stone or biliary stricture.

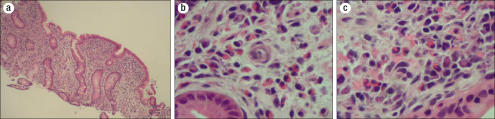

A gastroenterologist was then consulted for an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed to evaluate her history of hematemesis and revealed large, thickened, erythematous folds throughout the stomach and duodenum (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy results. (a) Endoscopic view showing thickened hypertrophic rugal folds in the body of the stomach. (b) The mucosa was erythematous and edematous on close inspection.

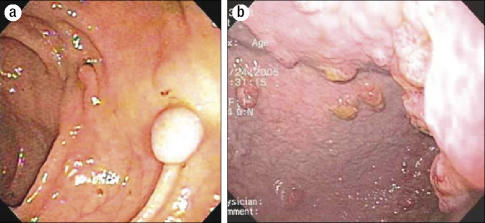

Gastric and duodenal biopsies showed a dense eosinophilic infiltrate, and the duodenal mucosa was “flat” (Figure 2). The differential diagnosis for blunted villi with a dense infiltrate of eosinophils on intestinal biopsy includes eosinophilic gastroenteritis, vasculitis, celiac sprue, parasitic infections, and lymphoma. Further workup to clarify her disease was performed. Upon review, her gallbladder pathology was unremarkable for a vasculitic process. Numerous serologic tests were performed (Table) but were nondiagnostic. The patient was given the preliminary diagnosis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis based on her symptoms and gastrointestinal eosinophilia without another identifiable cause. She was discharged on oral cromolyn 200 mg four times a day.

Figure 2.

(a) Low-power view demonstrating blunting of the villi.(b) Medium-power and (c) high-power views illustrating the prominent eosinophilia in the lamina propria of the duodenal mucosa.

Table.

Laboratory data

| Test | Value | Interpretation |

| Gliadin IgG (U/mL) | >100 | Elevated |

| Tissue transglutaminase IgG (U/mL) | 2 | Normal |

| Tissue transglutaminase IgA (U/mL) | 0.8 | Normal |

| Serum IgA | Normal | Normal |

| Antinuclear antibodies | 1:80 | Elevated |

| Stool ova and parasites | Negative | Normal |

| Gastrin level | Normal | Normal |

| Giardia antigen | Negative | Normal |

| Stool white blood cells | Negative | Normal |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hr) | 30 | Elevated |

| White blood cells (×109/L) | 6.8 | Normal |

| Eosinophils (%) | 9 | Elevated |

Ig indicates immunoglobulin.

She returned to the clinic 4 weeks later for follow-up. Since her previous discharge, she had lost approximately 7 kg and continued to experience severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Of interest, she also noticed patchy alopecia and atrophy of her nails that began shortly after her surgery (Figure 3). Hyperpigmentation of the skin around her temples also appeared. A small bowel radiological exam was performed to look for intestinal lymphoma, and this revealed diffuse intestinal polyposis (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Cutaneous symptoms. (a) Diffuse thinning of the hair began shortly after the cholecystectomy. (b) The patient's fingers and toes were affected by onychodystrophy (arrowheads).

Figure 4.

A small bowel radiograph with contrast revealed polyposis in the proximal small bowel (arrow).

The patient underwent a repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies, which revealed atrophic gastric mucosa and multiple polyps of the stomach, small bowel, and colon (Figure 5). The polyps were hamartomatous by pathologic criteria. Based on these findings and her clinical presentation, it was recognized that she had Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Figure 5.

Results of an upper endoscopic exam conducted 6 weeks after the initial study. (a) Polyps were scattered throughout the colon. (b) Atrophic gastric mucosa was present with retention-like polyps.

After the initial diagnosis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis, she underwent a 2-month course of prednisone at a dose of 20 mg per day, which did not relieve her symptoms. She then underwent treatment with a 3-week course of oral antibiotics (metronidazole 500 mg and Bactrim DS three times a day), without improvement in her clinical picture. Her persistent diarrhea, dehydration, and weight loss led to long-term parenteral hyperalimentation for approximately 12 months, which permitted maintenance of her weight. Because of the apparent autoimmune features of the disease, she was also treated with azathioprine and tacrolimus. Her clinical course has stabilized on high-dose antihistamines (fexofenadine 180 mg/day and ranitidine 300 mg/day) and azathioprine. She was eventually weaned off parenteral nutrition but still requires occasional parenteral iron for iron-deficiency anemia. Her nail and hair changes have resolved; however, she continues to suffer from chronic abdominal pain. After approximately 18 months of intensive therapy, she continues on antihistamines and azathioprine, does not require parenteral nutrition, and has not recovered her full strength.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is based on clinical, endoscopic, and pathological findings, including characteristic intestinal polyps, alopecia, onychodystrophy, and hyperpigmentation of the skin. In a Japanese study of 110 cases gathered from the literature, mental or physical stress was thought to be the most important risk factor for the onset of this syndrome (5); however, this may reflect our minimal understanding of this disease. In this case, abdominal pain occurred first, and the cutaneous symptoms appeared after the gallbladder surgery.

Early manifestations of CCS are nonspecific and often leave the clinician perplexed. Although typical for CCS, the initial symptoms of this patient fulfilled diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic gastroenteritis, but the development of alopecia, onychodystrophy, and gastrointestinal polyposis made it clear that CCS was the correct diagnosis. To our knowledge, this is the first case of CCS presenting as eosinophilic gastroenteritis.

Endoscopic characteristics of CCS can be quite impressive, as illustrated in our patient. Gastric mucosa has been described in the literature as both thickened and hypertrophied as well as atrophic and polypoid. Our patient manifested both of these findings as her disease progressed (Figures 1 and 5). The differing appearances reported in the literature, therefore, may simply be dependent on the timing of endoscopy in relation to the evolution of the disease. CCS is an acquired, nonfamilial polyposis syndrome in which hamartomatous polyps are distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Numerous case reports have suggested that CCS is associated with colorectal carcinoma (7). Adenomatous and malignant transformation of polyps in CCS has been reported. (7–11), but whether CCS is a risk factor for malignancy remains controversial.

Despite a number of intriguing hypotheses in the literature, the pathogenesis of CCS is unknown. Since CCS is a syndromic diagnosis based on a cluster of unusual clinical findings, it is possible that these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. One concept is that CCS is a result of an acquired autoimmune gastroenteritis (8). Evidence to support this view includes correlations between CCS with high titers of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and other autoimmune disorders (11). Our patient had high titers of ANA as well as a history of autoimmune-related hypothyroidism. The intense inflammatory infiltrate on mucosal biopsy is also consistent with an autoimmune process. The cutaneous features of CCS have been attributed to malnutrition; however, these findings sometimes precede the gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition, our patient was of normal weight and nutritional status when her cutaneous symptoms began, suggesting that these findings were not related to her eventual weight loss.

Another explanation for the pathogenesis of CCS involves the loss of stimuli for proliferative activity in the skin and gut mucosa (12). This would be a result of either a loss in epidermal growth factor or an acquired resistance to it. Alopecia, nail dystrophy, skin hyperpigmentation, and intestinal polyposis would then occur secondary to atrophy of these tissues. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to support such an etiology, and it is unclear whether the gut is hypo- or hyperproliferative. As an interesting if tangential possibility, a reported case of CCS has been linked to enteropathy from an unknown antigen and arsenic poisoning (13).

Current treatment strategies have not been proven to be consistently effective. The natural history of CCS includes progressive symptoms with spontaneous relapses, making it difficult to attribute any improvement to a specific therapy. Furthermore, the disease is rare, making prospective treatment trials a challenge. Therapies for CCS have focused on immunosuppression and stabilization of mast cells (2, 14). Acid suppression is also recommended in some cases in which high acid output is suspected (15). Reported therapeutic regimens have included prolonged courses of steroids, H1- and H2-receptor blockade, and oral cromolyn sodium. Nutritional support with parenteral nutrition is often indicated to treat malnutrition and will provide extra time for spontaneous improvement. Antibiotics have been employed to treat presumed possible bacterial overgrowth, but consistent resolution of symptoms is not seen. The use of anabolic steroids and surgical resection of focally involved segments of bowel have been tried with some success; however, these therapies are not widely used, and surgery would be hazardous in light of the diffuse nature of the mucosal inflammation (16).

The prognosis in CCS is poor, with a reported 5-year mortality rate of 55% (5). Fatal complications include gastrointestinal bleeding, sepsis, and congestive heart failure (3). Current therapies have been based on anecdotal evidence and idiosyncratic institutional experience. Further studies using new therapies and randomized placebo-controlled trials are needed. We were gratified that our patient's medical regimen and aggressive parenteral nutrition supplementation were apparently sufficient to delay the progression of her disease. We hope that her disease will eventually remit.

References

- 1.Cronkhite LW, Jr, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252(24):1011–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195506162522401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Pharmacological management of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(3):385–389. doi: 10.1517/14656566.4.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward E, Wolfsen HC, Ng C. Medical management of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. South Med J. 2002;95(2):272–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto A. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; observation of 180 cases reported in Japan. Nippon Rinsho. 1991;49(12):221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto A. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: epidemiological study of 110 cases reported in Japan. Nippon Geka Hokan. 1995;64(1):3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61(5):293–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakatsubo N, Wakasa R, Kiyosaki K, Matsui K, Konishi F. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with carcinoma of the sigmoid colon: report of a case. Surg Today. 1997;27(4):345–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00941810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murata I, Yoshikawa I, Endo M, Tai M, Toyoda C, Abe S, Hirano Y, Otsuki M. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(9):706–711. doi: 10.1007/s005350070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yashiro M, Kobayashi H, Kubo N, Nishiguchi Y, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome [comment] Digestion. 2005;71(4):199–200. doi: 10.1159/000076560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata J, Kijima H, Hasumi K, Suzuki T, Shirai T, Mine T. Adenocarcinoma and multiple adenomas of the large intestine, associated with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35(6):434–438. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi Y, Yoshikawa M, Tsukamoto N, Shiroi A, Hoshida Y, Enomoto Y, Kimura T, Yamamoto K, Shiiki H, Kikuchi E, Fukui H. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colon cancer, portal thrombosis, high titer of antinuclear antibodies, and membranous glomerulonephritis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(8):791–795. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeman K, Anthony PP, Miller DS, Warin AP. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a new hypothesis. Gut. 1985;26(5):531–536. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.5.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senesse P, Justrabo E, Boschi F, Goegebeur G, Collet E, Boutron MC, Bedenne L. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome and arsenic poisoning: fortuitous association or new etiological hypothesis? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23(3):399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadalavada R, Brown DK, Walker AN, Sedghi S. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: sustained remission after corticosteroid treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1444–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allbritton J, Simmons-O'Brien E, Hutcheons D, Whitmore SE. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of two cases, biopsy findings in the associated alopecia, and a new treatment option. Cutis. 1998;61(4):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanzawa M, Yoshikawa N, Tezuka T, Konishi K, Kaneko K, Akita Y, Mitamura K, Tsunoda A, Takada M, Kusano M. Surgical treatment of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with protein-losing enteropathy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(7):932–934. doi: 10.1007/BF02235381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]