‘... THAT MECCA OF PSYCHO-NEUROSES...’1

Craiglockhart is perhaps the most famous shell-shock hospital. It was set up to deal with the epidemic of psychological casualties created in the muddy trenches of the First World War; and, in particular, with the huge increase of casualties following the battle of the Somme in 1916. The hospital's fame is unsurprising in that two of the finest poets of a war over-flowing with poetic voices were treated there—Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. It was Sassoon who nicknamed the place ‘Dottyville’ in a letter of 1917.2

The hospital's literary importance has been established by Sassoon's memoirs, a stage play, the fine novels of Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy and a film version of the first of these novels.3 Yet its role has not always been accurately portrayed. Much of the emphasis has been on an unrepresentative doctor-patient relationship between Dr William Rivers and Siegfried Sassoon about which Sassoon wrote much after the war. The hospital has been conscripted by these misrepresentations into a simplistic view of shell-shock treatments delineated by rank: physical torture and humiliation for the other ranks (who were not treated at Craiglockhart), and a subtle reprogramming taking the form of friendly chats with avuncular doctors over tea and scones for the officer classes (who were).

Craiglockhart also has an important place in the development of British neuropsychiatry. The concept of a psychological stressor resulting in physical symptoms was still a relatively novel one in this period; the necessities of coping with an epidemic of psychological casualties in the context of the war allowed some fundamental aspects of Freud's ideas regarding repression and the unconscious to gain greater acceptance and currency in the medical profession. In addition, the previously presented chronology of the hospital appears to be inaccurate when the contemporary sources are examined together. The chronology offered here for the first time solves the glaring inconsistencies of the previous accounts.4 It has been possible to examine the hospital's admission and discharge registers and assess the destination of patients treated there as well as to systematically examine the accounts of the patients and staff to gain a clearer insight into their views and experiences, neither of which has been done before.

A MENTAL HOSPITAL AT WAR

Craiglockhart was open only for 28 months. Housed in a disused and down-at-heel ‘hydropathic’ hotel, or ‘hydro’, in the village of Slateford (now a suburb of Edinburgh), it was a place whose rooms and facilities must have seemed almost built for the purpose. The building still stands, today housing Edinburgh's Napier University.

In its short and eventful existence the hospital was inspected twice by the War Office: on each occasion the commanding officer was relieved of his position and another appointed. These administrative shake-ups illustrate very well the differing views held by the War Office and the ‘civilians in uniform’ working at Craiglockhart.5 (p. 15)

At the time it was opened in October 1916, Major William Bryce, a local physician, was made commanding officer. William Halse Rivers, the hospital's most celebrated member of staff, was transferred from his work at Maghull hospital for shell-shocked other ranks, and Arthur John Brock, an Edinburgh clinician and medical historian, also began to work there following experience in treating ‘neurasthenia’ before the war. We have all-too-brief references to other members of staff who nonetheless seem to have fitted in with the therapeutic regime which remained largely unchanged for a year following Craiglockhart's opening.

In October 1917, a War Office inspection took place. Shortly after this:

‘The commandant was notified that someone else would take over his commandancy, and the rest of the staff sent in their resignations as a demonstration of loyalty to him.’5(p. 47)

There was considerable antagonism between the ‘chief medical mandarins from the War Office’ and the doctors in uniform who ran Craiglockhart. The apathy arose from a fundamental scepticism concerning diagnosis as well as the therapeutic strategies suggested. The traditional military (and often societal) view was that shell-shock sufferers were ‘lead-swingers’ and malingerers who should be treated in an appropriately punitive fashion and not sent on holiday in the Scottish countryside. Sassoon wrote:

‘After the War Rivers told me that the local Director of Medical Services nourished a deep-rooted prejudice against [Craiglockhart], and actually asserted that he “never had and never would recognize the existence of such a thing as shell-shock”.’5 (p.15)

The next stage in the hospital's history saw the instigation of an unsympathetic and disciplinarian regime under Major Bryce's successor, Colonel Balfour Graham. The only description we have of this time comes from the novel England, Their England by A G Macdonnell—who was a patient at the hospital from April 1918—due in part to a significant gap in the surviving copies of The Hydra for this period (Figure 1). Macdonnell describes a ‘monster hydropathic’ under the unfortunate control of a kind of sadistic homeopath who ran the hospital on strict disciplinarian lines. The commandant's therapy, Macdonnell tells us:

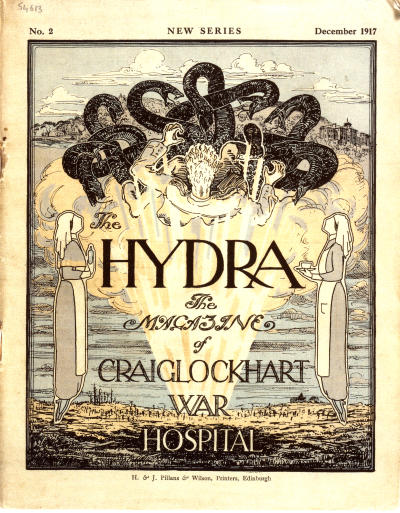

Figure 1.

The front cover of the Craiglockhart Hospital magazine, The Hydra, December 1917 [from the English Faculty Library, Oxford, UK, with permission]

‘... consisted of finding out the main likes and dislikes of each patient, and then ordering them to abstain from the former and apply themselves diligently to the latter... For example, those of the so-called patients... who disliked noise were allotted rooms on the main road. Those who had been, in happier times, parsons, school masters, journalists, and poets, were forbidden to use the library and driven off in batches to physical drill, lawn tennis, golf, and badminton.’6

This regime remained in place from November 1917 until around March 1918 when, perhaps because of decreasing therapeutic success, another inspection was prompted. We are told that during this period ‘the mental condition of as many as two per cent of the patients had definitely improved for the better’.7 However, Macdonnell's portrayal of the more psychologically aware, and perhaps from our perspective better intentioned and equipped, ‘busybodies’ with their ‘absurd technical knowledge and jargon’7 is hardly less sharp than his depiction of the misguided military homeopath, treating neurosis with neurosis-stimulant.

Following this second inspection, Professor William Brown—who had worked before the war at King's College London and played a crucial role in establishing shell-shock treatment centres behind the lines in France and Flanders—took over as camp commandant and remained until the hospital was closed in March 1919.

The chronologies previously given have proposed that A G Macdonnell's account refers to the time before Rivers' arrival, and imply that Rivers took charge after Colonel Balfour-Graham was relieved of his command. Macdonnell, however, did not arrive at the hospital until April 1918, some 18 months after the hospital opened and 6 months after Rivers' departure. In addition, this account relied on ignoring Macdonnell's suggestion that the ‘civilian Professor of psychology’ became officer in command, which Rivers never did. If Macdonnell was referring instead to Brown, and not Rivers, then all of these inconsistencies are removed. This is perhaps another example of the tendency to overemphasize Rivers' importance relating to Craiglockhart and the developing shell-shock treatments.

THE CURE BY FUNCTIONING

The hospital's cognitive therapy existed within a complementary framework of an ‘environmental’ active and behavioural approach created by Brock, which he termed ‘ergotherapy’ or the cure by functioning. The shell-shocked needed, in his view, to rediscover their links with an environment from which they had become detached. They could only do this through active and useful functioning; through working. Brock played a central part in organizing many activities in the hospital to provide his patients with a means of helping themselves back to health:

'If the essential thing for the patient to do is to help himself, the essential thing for the doctor to do—indeed, the only thing he can profitably do—is to help him to help himself.8 (p. 30)

Such activities were often based on the sporting and entertainment facilities at the hydro. However, Brock tended to frown on these as somewhat frivolous. As preferred alternatives he organized temporary teaching posts for soldiers at local schools, jobs at local farms assisting under-supported farmers, and he even fostered links with an Edinburgh sociological group to open the eyes and the ears of the men to the social deprivation and inequalities in the home-front society:

‘Are not these horrors of war the last and culminating terms in a series that begins in the infernos of our industrialized cities?’8(p. 40)

Brock believed that shell shock was not purely a wartime phenomenon but rather an ‘acute manifestation of a chronic condition’,8 a condition which could only be combated by the useful functioning of the individual in improving the immediate environment for himself and those around him.

Perhaps Brock's most important tool, both to communicate his aims to the patients and also as a form of therapy in itself, was The Hydra, the hospital magazine. The Hydra, the many-headed monster whose defeat was one of Hercules' most difficult labours, was to provide a jokey description of the character of the hospital—the officers, or heads, being removed (or discharged) only to be replaced by new inmates. It also provided a more serious analogy for the results of poorly carried out shell-shock treatment: the resurfacing of psychological problems in different, but equally distressing and incapacitating forms. The magazine was a vehicle through which the patients could express and share their experiences, as well as learn about the hospital ethos and activities. Brock's patient Wilfred Owen was editor of this monthly periodical for much of his time at the hospital, and had his first published poems within its pages. Indeed, Owen did not begin writing war poetry until Craiglockhart. This was due largely to his budding friendship with Siegfried Sassoon, but it was also due to Brock's encouragement: that he direct his artistic eye over his experiences and not his fantasies, to approach a cure by functioning. Perhaps the most famous anti-war poem, Dulce et decorum est was written at the hospital in 1917.

If Brock did not have the easy personability of Rivers, his methods did not require these skills of him. Some of his writings seem startingly modern and far-reaching in their early identification of the limits of a purely mechanistic scientific paradigm: it is unfortunate that they have not reached as wide an audience as Rivers' work has.

Rivers' relevance to Craiglockhart has been overstated. This has tended to overshadow the extent to which the regime of the hospital was moulded by his colleague Brock, as well as colleagues, such as Brown, who practiced a similarly practical—and particularly British brand of Freudianism.

REMOBILIZATION OR REHABILITATION?10

Fortunately, the hospital's admission and discharge summaries have survived, giving us an insight into the fate of the patients treated during Craiglockhart's short life, unavailable anywhere else. A study of these registers allows us to quantify the destination of the patients, and perhaps therefore to delineate the function of the hospital in terms of its supposed role purely in remobilizing men to the frontline. First, there is evidence that the register compilers at the hospital had a bias against psychological disorders. The diagnosis of ‘neurasthenia’ is entered almost routinely in the logbooks; yet it is subordinated to any physical complaint in the patient—however apparently insignificant. We find patients admitted with ‘migraine’, ‘glycosuria’, ‘gas poisoning’, ‘compound fracture of toe’, and even ‘haemarrhoids’. These are not obvious reasons to be sent to a shell-shock hospital and surely reflect an unwillingness to ascribe sick leave to a psychological factor.

Between October 1916 and March 1919, 1736 patients with shell shock were treated at the hospital. Of these, 735 were listed in the registers as ‘D. M. U.’ which seems to stand for discharged (or declared) medically unfit.11 [A thorough search of contemporary sources has failed to find a definite explanation for this abbreviation, and even the guide to abbreviations at the beginning of the registers fails to show it.] Of the soldiers listed as having been treated at Craiglockhart, 89 are recorded as having been given home service—usually in administrative or bureaucratic roles: 78 are listed as having been discharged to light duties, commonly training new recruits or assisting with military bases in Britain: 141 were transferred to other units for further treatment or because there were more appropriate places for their treatment to be continued elsewhere: and 758 in total were listed as having been returned to duty. We know, however, from corroborative sources, that in at least one case a patient listed as having been discharged ‘to duty’ was in fact transferred to a neighbouring unit for further treatment. [A G Macdonnell is listed thus, although a reference to his departure in The Hydra, which he himself edited, tells us that he was transferred to Bowhill, a neighbouring hospital which appears to have been for those who required longer-term rehabilitation than Craiglockhart could provide.]

Sassoon suggests that discharge to duty was a rarer occurrence even than the figures record. In a letter of 1917, he tells us:

‘... it is quite out of the question for a man who has been three months in a nerve-hospital to be sent back at once...’12

And he was to write after the war:

‘I was then duly passed for general service abroad—an event which seldom happened from [Craiglockhart].’5 (p. 51)

Towards the end of the hospital's life the entries in the registers—which are nowhere expansive—become even sparser than previously, and hardly any patients are listed as being for ‘light duties’ or ‘home service’. This might reflect either a real simplification—that all involved were either sent to active duty at the front, discharged as medically unfit—or, more probably, the register compilers took it as read that patients would not be sent straight back to duty. Sassoon's insistence that to be sent straight back to active service, as he was himself, was a rare occurrence is telling in this respect, together with his entry in the registers, which not only has the date entered under the usual ‘Discharged To Duty’ column, but also a hand-written addition (which occurs only once or twice in the remaining 1800 entries): ‘To Duty’.

The default column in the admission and discharge registers is the discharged to duty column and there are strong reasons to suppose that many of the numbers which we have for that destination are, in fact, examples of shortcuts taken in the filling in of the registers. Nevertheless, 978 officers in total were discharged entirely, transferred, or given alternative non-combative roles—destinations which Brock campaigned for and which he documents as being an increasingly useful and recognized option in the later stages of the war.13

‘WE DID NOT LIKE BEING SHELLED, BUT WE DID NOT RUN AWAY’14

Craiglockhart offers a fascinating window into the lives, experiences and desires of its patients and staff. This is well documented with reference to Owen and Sassoon. However, the pages of The Hydra extend to include the less literary people, men and women alike, who passed through its doors. Within its pages are a series of fascinating and revealing cartoons depicting, among other things, the traumatic nightmares most of those at the hydro suffered, Rivers' mystical reputation, and the often mixed feelings of soldiers on leaving the place. Poems and short stories written by patients and nurses allow us to gain an idea of the reaction of the local inhabitants to the bluearmbanded patients, to hear the doctors teaching their therapeutic and largely self-help strategy to their charges, and to measure the often less-than-welcoming responses from the men. We are also able to hear about the day-to-day activities of the hydro—from toy boat races to orchestral performances:

‘The programme was opened by the orchestra who played “Teddy Bear's Picnic” with some dash. It is one of the best things the orchestra has played to us...’

‘Mr Pockett played Schaun in a style which reminded us of George Formby, and kept the audience in roars of laughter at his antics...’14

Some less-accomplished poetry than the work of Owen or Sassoon shows us how conspicuous the officers with their blue bands and nervous walks felt during their time in Edinburgh:

Alone in this great drear city, ‘Mid throngs that never end, An object of scorn or of pity, And nowhere a friend.14

Another, published anonymously by ‘An Inmate’ and entitled simply ‘Stared At’, expresses a similar theme:

Now if I walk in Princes Street, Or smile at friends I chance to meet, Or, perhaps, a joke with laughter greet I'm stared at.14

It is easy to be misled by the stiff-upper-lip attitude and the forced jollity sometimes found in The Hydra into underestimating the degree of suffering within Craiglockhart's walls; and indeed, the often limited degree to which that suffering could be alleviated by the caring and the expertise of the staff. We should also bear in mind a simple but eloquent stanza from a poem in The Hydra:

Craiglockhart memories will be sad, Your name will never make us glad; The self-respect we ever had We've lost—all people think us mad.14

However, perhaps Owen and Sassoon are best able to prevent us being misled:

In the daytime, sitting in a sunny room, a man could discuss his psycho-neurotic symptoms with his doctor, who could diagnose phobias and conflicts and formulate them into scientific terminology. Significant dreams could be noted down, and Rivers could try to remove repressions. But by night each man was back in his doomed sector of horrorstricken Front Line, where the panic and stampede of some ghastly experience was re-enacted among the livid faces of the dead. No doctor could save him then, when he became the lonely victim of his dream disasters and delusions5 (p. 54):

Always (they) must see these things and hear them, Batter of guns and shatter of flying muscles'.15

And, of course, in Dulce et decorum est:

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.16

Owen wrote to his mother after finishing the poem: ‘The famous Latin tag means of course, it is sweet and meet to die for one's country. Sweet! And decorous!’17

SAVING THE SHELL SHOCKED18

Craiglockhart gives us a unique perspective on the human experience of war, as well as on the changing medical and psychiatric beliefs and practices of the early 20th century. This has continuing salience given the renewed conflict of recent years and the approaching First World War centenary.

The medical profession's response to the shell shock ‘problem’, in the context of the war, was not uniform, either in aim or in execution. This was true at Craiglockhart and also at comparable, non-commissioned soldiers' hospitals such as Maghull. The hospital was part of a desperate and disparate set of responses to the problems posed by the reality of the shell-shock epidemic. While the physicians' success in healing the shell-shocked is hard to measure, it appears that, to their patients, they were often less re-programmers than ‘saviours’.18

Acknowledgments With deepest thanks to my father, Mr M R Webb, and mother, Dr V E S Webb, for help with all the drafts of this work. Thanks also to Dr Tilly Tansey and Dr Michael Neve at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, as well as the late Professor Roy Porter for all of their encouragement and advice.

Competing interests None declared.

References

- 1.Siegfried Sassoon, Sherston's Progress. London: Faber & Faber: 38

- 2.Letter to Robbie Ross, 26July 1917. Sassoon Papers. London: Imperial War Museum

- 3.Sassoon Seigfried. The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston. London: Faber & Faber,1981. ;; Pat Barker, The Regeneration Trilogy. London: Viking, 1991. Regeneration, film based on Pat Barker, directed by Gilles Mckinnon, and released on DVD. London: Artificial Eye, 1997. Not About Heroes, stage play by Stephen McDonald. Admission and Discharge Registers For Craiglockhart War Hospital. PRO MH 106. Kew: Public Record Office, 1887-1902. Anonymous account of Craiglockhart, Rivers Papers. London: Imperial War Museum Archive

- 4.The Chronology of the hospital in the previous accounts (e.g. Leese Paul J. The Social And Cultural History Of Shellshock [PhD Thesis]. Milton Keynes: Open University, 1989;; Showalter Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830-1980. London: Virago,1987. ;; Slobodin Richard. W. H. R. Rivers. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978) all start their accounts with a description of based on; Macdonnell AG. England, Their England, 1933. , which is discussed later in this article

- 5.Sassoon Siegfried. Sherston's Progress. London: Faber & Faber, 1936. ‘A handful of highly-qualified civilians in uniform were up against the usual red-tape ideas... the military authorities regarded [war hospitals for nervous disorders] as experiments which needed careful watching and firm handling.’ (p. 15). Sassoon changes the name of the hospital to Slateford, the village close to the hydro building (p. 15)

- 6.Macdonnell AG. England, Their England London: Macmillan, 1936:17 -18

- 7.Craiglockhart War Hospital Admission and Discharge Registers.PRO MH 106 . Kew: Public Record Office,1902 1887

- 8.Brock Arthur John. The Re-Education of the Adult: The Neurasthenic In war and Peace. Sociol Rev 1918. ;X:25 -41 (see p. 30) [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Hydra [www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/jtap/hydra] Accessed 11.1.06

- 10.Stone Martin. Shellshock and the psychologists. In: Bynum W, Porter R, Shepherds M, eds. The Anatomy of Madness, Vol.2 , Chap. 2. London: Tavistock, 1985:242 -71. Stone, perhaps, best sums up the traditional view of Craiglockhart's supposed purpose: ‘designed to bring about the rapid return of soldiers to the front line before they were “lost in the system”’ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archives MH 106. Kew: Public Record Office,18931889 1887. especially

- 12.Sassoon Siegfried. Diaries,1915-18. London: Rupert Hart-Davies: 190

- 13.Brock Arthur John. The Re-Education of the Adult: The Neurasthenic In war and Peace. Sociol Rev 1918. ;X25 -41. ‘Happily we see on every side signs that the authorities are becoming alive to this fact. These officers, when unsuited for further combatant duty or even for home service, are now being taken by other State Departments—as by the Boards of Shipping, Agriculture, Timber Supply, Munitions—and, when properly selected, they seldom fail to acquit themselves with the greatest credit.’ [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Hydra, April 28th1917. ;; July 7th 1917;; December 1917, Editorial & June 1918

- 15.Owen Wilfred. Mental cases. In: Stallworthy Jon, ed. Wilfred Owen: the Complete Poems and Fragments. London: Chatto & Windus, 1983:117

- 16.Owen Wilfred. Dulce et Decorum Est.. In: Stallworthy Jon, ed. Wilfred Owen: the Complete Poems and Fragments. London: Chatto & Windus, 1983:117

- 17.Owen Wilfred. Letter No. 552. In: Owen H, Bell J. Wilfred Owen:Collected Letters . Oxford: OUP, 1967

- 18.A previous volunteer at Craiglockhart Hospital written following Rivers' early death. Dr Rivers and the Young Officers. Times 14 June1922

- 19.Shephard Ben. ‘The Early Treatment Of Mental Disorders’. R.G. Rows and Maghull 1914-18. In: Berrios GE, Freeman H, eds. 150 Years Of British Psychiatry. London: Athlone,1991