Abstract

BACKGROUND

Measuring and reporting patients' experiences with health plans has been routine for several years. There is now substantial interest in measuring patients' experiences with individual physicians, but numerous concerns remain.

OBJECTIVE

The Massachusetts Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey Project was a statewide demonstration project designed to test the feasibility and value of measuring patients' experiences with individual primary care physicians and their practices.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional survey administered to a statewide sample by mail and telephone (May–August 2002).

PATIENTS

Adult patients from 5 commerical health plans and Medicaid sampled from the panels of 215 generalist physicians at 67 practice sites (n=9,625).

MEASUREMENTS

Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey produces 11 summary measures of patients' experiences across 2 domains: quality of physician-patient interactions and organizational features of care. Physician-level reliability was computed for all measures, and variance components analysis was used to determine the influence of each level of the system (physician, site, network organization, plan) on each measure. Risk of misclassifying individual physicians was evaluated under varying reporting frameworks.

RESULTS

All measures except 2 achieved physician-level reliability of at least 0.70 with samples of 45 patients per physician, and several exceeded 0.80. Physicians and sites accounted for the majority of system-related variance on all measures, with physicians accounting for the majority on all “interaction quality” measures (range: 61.7% to 83.9%) and sites accounting for the largest share on “organizational” measures (range: 44.8% to 81.1%). Health plans accounted for neglible variance (<3%) on all measures. Reporting frameworks and principles for assuring misclassification risk ≤2.5% were identified.

CONCLUSIONS

With considerable national attention on the importance of patient-centered care, this project demonstrates the feasibility of obtaining highly reliable measures of patients' experiences with individual physicians and practices. The analytic findings underscore the validity and importance of looking beyond health plans to individual physicians and sites as we seek to improve health care quality.

Keywords: doctor-patient relationship, primary care, quality measurement, patient-centered care

The past dozen years have seen unprecedented investments in developing and testing health care quality measures. Yet, by most accounts, we remain in the very early stages of these endeavors.1,2 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Crossing the Quality Chasm highlighted the challenges of achieving a truly outstanding health care delivery system.3 Patient-centeredness was 1 of 6 priority areas identified as having vastly inadequate performance. With this, patient-centered care went from being a boutique concept to a widely sought goal among health care organizations nationwide.

These events heightened the importance of patient surveys as essential tools for quality assessment. A well-constructed survey offers a window into patient experiences that is otherwise unavailable. Surveys measuring patients' experiences with health plans are already widely used, with results reported annually through the National Committee on Quality Assurance and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. However, the limitations of measuring quality only at the health plan level have become clear.4–6 In the late 1990s, several initiatives began developing surveys measuring patients' experiences with medical groups and then, increasingly, with individual physicians. The Massachusetts Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey (ACES) Project, a statewide demonstration project conducted in 2002 to 2003, is the most extensive such effort completed to date.

The ACES Project involved a collaboration among 6 payers (5 commercial health plans and Medicaid), 6 physician network organizations, and the Massachusetts Medical Society working through Massachusetts Health Quality Partners. The project sought to address 3 principal concerns related to the feasibility and merit of this form of measurement: (1) ascertaining sample sizes required to achieve highly reliable physician-specific information; (2) evaluating the need for plan-specific samples within physicians' practices; and (3) establishing the extent to which patients' experiences are influenced by individual physicians, practice sites, physician network organizations, and health plans.

METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

Sample frames were provided by the 6 payer organizations. Files from the 5 commercial plans included all adult members in the plan's HMO product, and for each member, provided a primary care physician identifier. Because the Medicaid Primary Care Clinician (PCC) Plan registers members to sites, not physicians, Medicaid provided primary care site identifiers for each member. A linked sampling file was created using available physician and site identifiers.

Because a principal objective of the study was to estimate plan-physician interaction effects, physicians had to have at least 75 patients in each of two or more commercial plans to be eligible. Practice sites were eligible if they had at least 2 adult generalist physicians, and if at least two-thirds of the site's physicians were eligible. Because the majority of adult generalists in Massachusetts are in settings with at least 4 physicians (81%) and accept multiple payers, these criteria caused few exclusions except among physicians in solo practice (6.9%) and in two-to-three physician practices (12.1%) wherein one or more physicians had an extremely limited panel. We worked with leadership at each of the 6 Physician Network Organizations to identify eligible practice sites statewide.

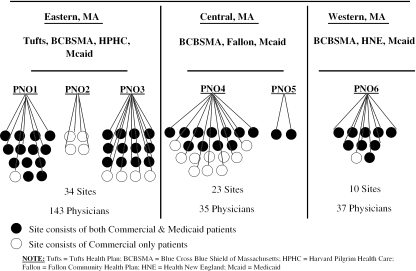

We randomly sampled 200 commercially insured patients from each physician's panel, stratifying by health plan, with plan allocations as equal as possible within physician samples. Most physician samples drew patients from 2 commercial plans, but some panels afforded sample from 3. Primary Care Clinician enrollees were selected by identifying sites from the sample that had at least 200 PCC enrollees and drawing a starting sample of approximately 100 PCC enrollees per site. The study's starting sample (n=44,484) included 39,991 commercially insured patients from the practices of 215 generalist physicians at 67 sites, and 4,493 Medicaid PCC enrollees from 47 of these sites (see Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Sampling framework.

Data Collection

The ACES administered to study participants was developed for the project, drawing substantially upon existing validated survey items and measures.4,7,8 The survey's conceptual model for measuring primary care corresponds to the IOM definition of primary care.9 Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey extends beyond previous similar measures of these domains in ways suggested by our National Advisory Committee, which included national and local organizations representing physicians, patients, purchasers, health plans, and accreditors. The survey produces 11 summary measures covering 2 broad dimensions of patients' experiences: quality of physician-patient interactions (communication quality, interpersonal treatment, whole-person orientation, health promotion, patient trust, relationship duration) and organizational features of care (organizational access, visit-based continuity, integration of care, clinical team, and office staff). All measures range from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores indicating more favorable performance. The initial survey question named the primary care physician indicated by the respondent's health plan and asked the respondent to confirm or correct this. For Medicaid, respondents confirmed or corrected the primary care site, and then wrote-in their primary care physician's name.

Data were obtained between May 1 and August 23, 2002 using a 5-stage survey protocol involving mail and telephone.10 The protocol included an initial survey mailing, a reminder postcard, a second survey mailing, a second reminder postcard, and a final approach to all nonrespondents using either mail (commercially insured) or telephone (Medicaid). For Medicaid enrollees, mailings included both English and Spanish materials, and telephone interviews were available in both languages. Costs per completed survey were $10 for commercial and $24 for Medicaid.

This protocol yielded 12,916 completed surveys (11,416 commercial, 1,304 Medicaid) for a response rate of 30% after excluding ineligibles (n=1,716). On average, 58 completed questionnaires per physician were obtained (SD=14.4). Nonresponse analyses are summarized here, with further detail provided at [available online at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00311.x/suppl_file/JGI+311+Supplementary+Material.doc]. As is customary in survey research, nonresponse was higher among younger, poorer, less educated, and nonwhite individuals.11–13 To evaluate whether nonresponse threatened the data integrity for physician-level analysis, we evaluated whether the nature or extent of nonresponse differed by physician. Using U.S. Census block group-level data for the full starting sample (n=44,484), we evaluated whether the factors associated with individuals' propensity to respond (e.g., age, race, education, socioeconomic status) differed by physician. There were no significant interactions between propensity to respond14 and physician—signifying that the lower propensity of certain subgroups applied equally across physicians. To evaluate whether differential response rates among physicians threatened data integrity, we evaluated whether the timing of survey response differed by physician. Previous research suggests that late responders report more negative experiences than initial responders, and that late responders' characteristics and experiences approximate those of nonrespondents.15–17 While some evidence suggests that early and late responders are equivalent,18–20 no research has found more favorable views among late responders. We found no significant interactions between stage of survey response and physician (P>.20). Overall, nonresponse analyses suggest that differential response rates across physicians (15% to 35%) were associated with effects no greater than 0.8 points, which are approximately one-seventh the size of true physician-level differences observed for the ACES measures. Thus, despite a relatively low response rate, nonresponse analyses suggested that the nature of nonresponse does not vary significantly by physician, and that the extent of nonresponse does not vary sufficiently to threaten the integrity of physician-level analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses included all respondents who confirmed having a primary care physician, whose physician was part of the original sample, and who reported at least one visit with that physician in the past 12 months (n=9,625). In the commercial sample, these criteria excluded 790 respondents who indicated that the plan-named physician was incorrect (6.9%) and 1,129 respondents who reported no qualifying visits (11%). For Medicaid, the criteria excluded 732 respondents who either did not name a primary physician or named a physician not included in the study sample.

We compared the sociodemographic profiles, health, and care experiences of commercial and Medicaid samples. Next, we calculated the physician-level reliability (αMD) of items and scales under varying sample size assumptions using intraphysician correlation and the Spearman Brown Prophecy Formula.21 The physician-level reliability coefficient (αMD) signifies the level of concordance in responses provided by patients within physician samples (range: 0.0 to 1.0). The Spearman Brown Prophecy Formula estimates reliability for projected sample sizes in the same way that estimated standard error allows studies to estimate the accuracy of a mean in a proposed experiment, and thus allowed us to determine measure reliability under varying sample size assumptions.

Next, we estimated the probability of incorrectly classifying a physician's performance (“risk of misclassification”) using the Central Limit Theorem of statistics to compute the expected percentage of physicians who would be misclassified to the next lower performance category under varying levels of measurement reliability (αMD=0.70 to 0.90). The Central Limit Theorem asserts that, for an individual physician, the observed mean score across multiple independent patients is approximately normally distributed around a physician's true mean score. This applies here because scores are limited to a 0 to 100 range, the patients are independent, and the statistic in question is a sample average for an individual physician. This fact allows us to estimate, for an individual physician, the probability of being misclassified within any range of scores. With additional information on the distribution of true mean scores in a population of physicians, we can make unconditional misclassification probability estimates for that physician population.

Finally, we used Maximum Likelihood Estimation methods22 to determine the influence of each level of the system (physician, site, network organization, plan) on each ACES measure, controlling for patient characteristics (age, sex, race, years of education, number of chronic medical conditions) and for system interaction effects (i.e., plan-site and plan-MD interactions).

RESULTS

Commercial and Medicaid samples differed significantly on most sociodemographic and health characteristics (Table 1)Medicaid enrollees reported shorter primary care relationships than commercially insured (P≤.05), but otherwise reported similar primary care experiences. Where differences occurred, trends favored the experiences reported by Medicaid enrollees somewhat.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Analytic Sample, Unadjusted

| Total Sample (n=9,625) | Commercial (n=9,053) | Medicaid (n=572) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 47.2 (12.5) | 47.4 (12.5) | 44.9 (12.4) | .000 |

| ≤25 (%) | 4.3 | 4.1 | 7.4 | .000 |

| 26 to 40 (%) | 26.6 | 26.4 | 30.7 | .026 |

| 41 to 64 (%) | 63.1 | 63.3 | 59.4 | .065 |

| 65+ (%) | 6.0 | 6.2 | 2.5 | .000 |

| Female | 67.0 | 66.5 | 76.0 | .000 |

| Race | ||||

| White (%) | 91.5 | 92.0 | 84.6 | .000 |

| Black (%) | 3.8 | 3.7 | 5.3 | .062 |

| Asian (%) | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.4 | .155 |

| Hispanic (%) | 2.9 | 2.4 | 12.2 | .000 |

| High school diploma (%) | 94.8 | 96.2 | 72.3 | .000 |

| Health | ||||

| Chronic conditions (mean, SD)* | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.8) | .000 |

| Hypertension (%) | 29.0 | 28.5 | 37.3 | .000 |

| Angina/coronary artery disease (%) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 8.8 | .000 |

| CHF (%) | 1.3 | 1.1 | 4.8 | .000 |

| Diabetes (%) | 7.9 | 7.4 | 16.1 | .000 |

| Asthma (%) | 14.0 | 13.0 | 30.1 | .000 |

| Arthritis (%) | 15.4 | 14.4 | 32.5 | .000 |

| Depression (%) | 21.8 | 19.5 | 57.3 | .000 |

| Overall health (% rated health as “poor”) | 1.6 | 0.9 | 12.4 | .000 |

| Health care | ||||

| Duration of current primary relationship (y, %) | ||||

| <1 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 5.1 | .003 |

| 1 to 5 | 42.9 | 42.4 | 50.5 | .000 |

| >5 | 48.7 | 49.0 | 44.4 | .034 |

| Organizational/structural features of care (mean, SD) | ||||

| Organizational access | 77.6 (22.6) | 77.5 (22.7) | 79.9 (21.2) | .045 |

| Visit-based continuity | 80.8 (27.2) | 80.8 (27.3) | 80.9 (26.5) | .906 |

| Integration of care | 78.3 (19.5) | 78.1 (19.6) | 81.1 (18.5) | .005 |

| Clinical team | 75.3 (21.8) | 75.2 (21.7) | 76.7 (23.6) | .222 |

| Quality of interactions with primary physician | ||||

| Communication (mean, SD) | 88.5 (18.5) | 88.5 (18.5) | 88.5 (19.5) | .986 |

| Whole person orientation (mean, SD) | 64.6 (24.2) | 64.2 (24.1) | 71.4 (23.7) | .000 |

| Health promotion (mean, SD) | 64.2 (33.5) | 63.6 (33.4) | 73.9 (32.6) | .000 |

| Interpersonal treatment (mean, SD) | 90.3 (16.5) | 90.4 (16.4) | 88.7 (18.8) | .023 |

| Patient trust (mean, SD) | 79.4 (22.4) | 79.3 (22.3) | 81.0 (24.1) | .077 |

| Had flu shot (%) | 37.6 | 37.9 | 32.9 | .020 |

From a checklist of 11 chronic conditions with high prevalence among U.S. adults aged 65 and older.3

CHF, congestive heart failure.

With samples of 45 patients per physician, all ACES measures except 2 (clinical team, office staff) achieved physician-level reliability (αMD) exceeding 0.70, and several measures exceeded αMD=0.80 (Table 2)Sample sizes required to achieve αMD≥0.90 generally exceeded 100 patients per physician. Variability among physicians, as measured by the standard deviation of the physician effect (SDMD), averaged 6.0 points on “organizational” features of care (range: 3.7 to 10.5) and 7.2 points on “interaction quality” measures (range: 4.1 to 13.9).

Table 2.

MD-Level Reliability and Sample Size Requirements of PCP-ACES Measures

| MD Reliability (n=45 Patients Per Physician) | Sample Size Requirements By Varying MD-Level Reliability Thresholds, αMD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDMD | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | ||

| Organizational/structural features of care | |||||

| Organizational Access,*α=0.80 | 0.81 | 6.6 | 24 | 42 | 95 |

| When you needed care for an illness or injury, how often did your personal doctor's office provide care as soon as you needed it | 0.74 | 5.9 | 37 | 64 | 144 |

| When you called your personal doctor's office in the evening or on weekends, how often did you get the help or advice you needed | 0.70 | 7.4 | 44 | 76 | 172 |

| When you scheduled a check-up or routine care, how often did you get an appointment as soon as you needed it | 0.82 | 8.4 | 22 | 38 | 87 |

| Visit-based continuity,*α=0.67 | 0.89 | 10.5 | 13 | 22 | 51 |

| When you were sick and went to the doctor, how often did you see your personal doctor (not an assistant or partner) | 0.92 | 15.2 | 9 | 16 | 37 |

| When you went for a check-up or routine care, how often did you see your personal doctor (not an assistant or partner) | 0.86 | 8.4 | 16 | 28 | 64 |

| Integration,*α=0.85 | 0.72 | 4.5 | 41 | 71 | 159 |

| When your personal doctor sent you for a blood test, x-ray, or other test, did someone from your doctor's office follow-up to give you the test results | 0.79 | 9.2 | 27 | 47 | 105 |

| When your personal doctor sent you for a blood test, x-ray, or other test, how often were the results explained to you as clearly as you needed | 0.70 | 6.4 | 45 | 78 | 176 |

| How would you rate the quality of specialists your personal doctor has sent you to | 0.52 | 3.2 | 98 | 168 | 378 |

| How would you rate the help your personal doctor's office gave you in getting the necessary approval for your specialist visits | 0.64 | 4.2 | 59 | 102 | 230 |

| How often did your personal doctor seem informed and up-to-date about the care you received from specialist doctors | 0.65 | 5.8 | 55 | 94 | 213 |

| How would you rate the help your personal doctor gave you in making decisions about the care that specialist(s) recommended for you | 0.67 | 5.3 | 50 | 86 | 195 |

| Clinical team,*α=0.87 | 0.57 | 3.7 | 78 | 134 | 302 |

| How often did you feel that the other doctors and nurses you saw in your personal doctor's office had all the information they needed to correctly diagnose and treat your health problems | 0.53 | 3.9 | 92 | 159 | 358 |

| How would you rate the care you got from these other doctors and nurses in your personal doctor's office | 0.57 | 3.6 | 80 | 137 | 309 |

| Office staff,*α=0.88 | 0.69 | 4.6 | 46 | 79 | 178 |

| How often did office staff at your personal doctor's office treat you with courtesy and respect | 0.65 | 4.1 | 55 | 95 | 214 |

| How often were office staff at your personal doctor's office as helpful as you thought they should be | 0.70 | 5.1 | 45 | 78 | 175 |

| Physician-patient interactions | |||||

| Communication,*α=0.92 | 0.72 | 4.3 | 40 | 68 | 155 |

| How often did your personal doctor explain things in a way that was easy to understand | 0.71 | 4.3 | 43 | 74 | 167 |

| How often did your personal doctor listen carefully to you | 0.73 | 4.9 | 39 | 67 | 152 |

| How often did your personal doctor give you clear instructions about what to do to take care of health problems or symptoms that were bothering you | 0.66 | 4.1 | 54 | 93 | 211 |

| How often did your personal doctor give you clear instructions about what to do if symptoms got worse or came back | 0.64 | 4.4 | 58 | 100 | 227 |

| Whole-person orientation,*α=0.90 | 0.83 | 7.5 | 21 | 37 | 83 |

| How would you rate your personal doctor's knowledge of your medical history | 0.81 | 6.7 | 24 | 41 | 94 |

| How would you rate your personal doctor's knowledge of your responsibilities at home, work or school | 0.79 | 7.6 | 27 | 47 | 105 |

| How would you rate your personal doctor's knowledge of you as a person, including values and beliefs important to you | 0.82 | 8.8 | 22 | 38 | 87 |

| Health promotion,*α=0.82 | 0.71 | 7.7 | 42 | 72 | 163 |

| Did your personal doctor give you the help you wanted to reach or maintain a health body weight | 0.66 | 9.7 | 55 | 94 | 212 |

| Did your personal doctor talk with you about specific things you could do to improve your health or prevent illness | 0.66 | 9.2 | 54 | 94 | 211 |

| Did your personal doctor give you the help you needed to make changes in your habits or lifestyle that would improve your health or prevent illness | 0.65 | 9.2 | 56 | 96 | 217 |

| Did your personal doctor ever ask you about whether your health makes it hard to do the things you need to do each day (such as at work or home) | 0.56 | 8.1 | 83 | 142 | 320 |

| Did your personal doctor give the attention you felt you needed to your emotional health and well-being | 0.61 | 7.0 | 66 | 114 | 258 |

| Interpersonal treatment,*α=0.85 | 0.75 | 4.1 | 35 | 60 | 136 |

| How often did your personal doctor treat you with respect | 0.60 | 2.5 | 69 | 119 | 268 |

| How often was your personal doctor caring and kind | 0.72 | 4.0 | 41 | 71 | 161 |

| How often did your personal doctor spend enough time with you | 0.75 | 6.1 | 34 | 59 | 134 |

| Patient trust,*α=0.83 | 0.74 | 5.4 | 37 | 63 | 143 |

| How often did you feel you could tell your personal doctor anything, even things you might not tell anyone else | 0.73 | 7.9 | 39 | 68 | 153 |

| How often did you feel that your personal doctor had all the information needed to correctly diagnose and treat your health problems | 0.65 | 4.4 | 57 | 97 | 220 |

| How often did your personal doctor put your best interests first when making recommendations about your care | 0.69 | 4.6 | 47 | 80 | 182 |

| Relationship duration | 0.95 | 13.9 | 5 | 9 | 22 |

| How long has this person been your doctor | 0.95 | 13.9 | 5 | 9 | 22 |

All items asked the respondent to report with reference to the last 12 months.

PCP, primary care physicians; ACES, Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey.

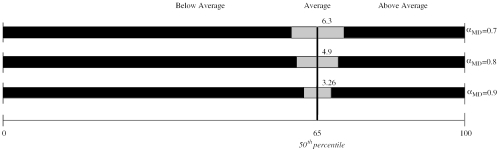

Analyses of misclassification risk highlighted 3 important influences: (1) measurement reliability (αMD), (2) proximity of a physician's score to the performance cutpoint, and (3) number of performance cutpoints.Table 3 illustrates diminishing probability of misclassification for scores more distal to a performance cutpoint (column 1), and with higher measurement reliability (αMD). The findings suggest the usefulness of establishing a “zone of uncertainty” around performance cutpoints to denote scores that cannot be confidently differentiated from the cutpoint score. The logic is very similar to that of confidence intervals and, in the illustration provided (Table 3)diagram), is equivalent to a 95% confidence interval. Note that higher measurement reliability affords smaller uncertainty zones (i.e., ±3.26 points vs 6.3 points). In this illustration, 3 performance categories are established, and risk of misclassification to the next-lower category is no greater than 2.5%. That is, a physician whose true score is “above average,” has no more than 2.5% risk of being observed as “average” with a given respondent sample. A performance report imposing multiple cutpoints would require this buffering around each cutpoint in order to maintain the desired level of classification certainty. Thus, even with highly reliable measures, going beyond 2 or 3 cutpoints appears ill-advised in the complexity and overlapping uncertainty zones that would likely result.

Table 3.

Risk of Misclassification for Mean Scores with Varying Proximity to the Performance Cutpoint and with Measures Varying in MD-Level Reliability

Table 4 reveals that, on average, 11% of variance in the measures (range: 5.0% to 22.1%) was accounted for by our models. Of the variance accounted for by the delivery system (physician, site, network, plan), individual physicians and practice sites were the principal influences. For organizational features of care, sites accounted for a larger share of system-related variance than physicians (range: 44.8% to 81.1%), but the physician contribution was substantial (range: 17.8% to 39.4%). For all measures of “interaction quality,” physicians accounted for the majority of system-related variance (range: 61.7% to 83.9%), though sites played a substantial role (range: 22.4% to 38.3%). Networks accounted for no variance except on 3 measures (organizational access, visit-based continuity, office staff). Health plans accounted for negligible variance on all measures.

Table 4.

Allocation of Explainable Variance in Each Measure Across Four Levels of the Delivery System

| Variance Explained by | Percent of Delivery System Variance Accounted for by Each Level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Patient Characteristics | Delivery System Effects | Physician | Practice | Network Organization | Health Plan | |

| Organizational/structural features of care | |||||||

| Organizational access | 12.9 | 3.5 | 9.4 | 39.4 | 44.8 | 15.8 | 0.0 |

| Visit-based continuity | 22.1 | 5.1 | 16.9 | 36.4 | 55.7 | 8.0 | 0.0 |

| Integration | 10.6 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 22.9 | 77.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Clinical team | 5.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 17.8 | 81.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Office staff | 8.6 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 21.0 | 62.8 | 13.7 | 2.5 |

| Physician-patient interactions | |||||||

| Communication | 8.6 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 61.7 | 38.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Whole-person orientation | 15.3 | 6.5 | 8.8 | 74.1 | 24.9 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Health promotion | 8.0 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 77.0 | 22.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Interpersonal treatment | 9.2 | 2.6 | 6.6 | 83.9 | 15.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Patient trust | 9.5 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 70.0 | 28.8 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

Plan-physician interaction effects were less than 2 points for all measures, and were zero for 5 measures, suggesting that experiences in a physician's practice do not differ meaningfully by plan (commercial payers). ANOVA models testing Medicaid-physician interaction effects suggest that these findings generalize to Medicaid. That is, within a physician's panel, Medicaid enrollees produced results that were identical or nearly identical to those of commercial patients.

DISCUSSION

This demonstration project addresses several important questions concerning the feasibility and merit of measuring patients' experiences with individual physicians. Perhaps most importantly, the measures showed high physician-level reliability with samples of 45 patients per physician, and at these levels of reliability, the risk of misclassification was low (≤2.5%) given a reporting framework that differentiated 3 levels of performance. However, the results also underscored that high misclassification risk is inherent for scores closest to the performance cutpoint (“benchmark”) and where multiple cutpoints are introduced. Thus, reporting protocols will need to limit the number of performance categories, and determine how to fairly handle cases most proximal to performance cutpoints, where misclassification risk will be high irrespective of measurement reliability. Also importantly, the study showed that individual physicians and practice sites are the principal delivery system influences on patients' primary care experiences. Network organizations and health plans had little apparent influence. These findings accord with previous analyses of practice site, network, and health plan influences on patients' experiences,4,23 but extend beyond previous work by estimating the effects of individual physicians within practices sites.

The results address several persistent concerns about physician-level performance assessment. First, the difficulties of achieving highly reliable performance measures have been noted for condition-specific indicators, given limited sample sizes in most physicians' panels, even for high prevalence conditions like diabetes and hypertension.2,24,25 Because the measures evaluated here apply to all active patients in a physician's panel, sample sizes required for highly reliable measures are easily met. Second, questions about whether measurement variance can be fairly ascribed to physicians themselves versus to the systems in which they work and the patients they care for have been prominent a concern.24–27 In this study, physicians and sites accounted for the vast majority of delivery system variance for all measures, but there was substantial sharing of variance between physicians and sites. The results suggest a shared accountability for patients' care experiences and for improving this aspect of quality.

Importantly, although, a substantial amount of variance on all measures remained unaccounted for. Although the delivery system variance accounted for here is considerably higher than that accounted for in studies of other types of performance indicators,24,26,28 it nonetheless raises a critical question for the quality field: Is it legitimate to focus on the performance of physicians and practices when there are so many other influences at play? This seems analogous to questioning whether clinicians ought to focus on particular known clinical factors, such as blood cholesterol levels, even when these factors only account for a modest share of disease risk. As with health, the influences on quality are multifactorial. Because there is not likely to be a single element that substantially determines any dimension of quality, we must identify factors that show meaningful influence and are within the delivery system's purview. In this study, average performance scores across the physician population spanned more than 20 points out of 100. This suggests that meaningful improvement can be accomplished simply by working to narrow this differential. The well-documented benefits of high quality clinician-patient interactions—including patients' adherence to medical advice,29–33 improved clinical status,34–37 loyalty to a physician's practice,38 and reduced malpractice litigation39–41—suggest the value of doing so.

As with any area of quality measurement, however, there are costs that must be considered against the value of the information. Data collection costs associated with this study suggest that obtaining comparable information for adult primary care physicians statewide (n=5,537) would cost approximately $2.5 million- or 50-cents per adult resident. Extrapolating to adult primary care physicians nationally (n=227,698), “per capita” costs across U.S. adults appear similar. Of course costs of such an initiative are highly sensitive to numerous variables—including the frequency, scope and modes of data collection6—and thus can only be very roughly gauged from this initiative. But a serious investment would clearly be required to accomplish widespread implementation of such measures, and while several such initiatives are currently underway,42–45 the potential for sustaining and expanding upon these over the long term remains unclear.

There are several relevant study limitations. First, the study included only patients of managed care plans (commercial and Medicaid). For other insurance products, where payers are not explicitly aware of members' primary care arrangements, a different sampling methodology would be required. Second, the initiative was limited to one state. In other geographic areas, individual plan effects could be larger, although previous evidence from national studies suggests these are unlikely to be of a magnitude necessitating plan-specific samples in a physician's practice.4,23 Finally, the measures here do not afford information on technical quality of care. Methodologies other than patient surveys are required for that area of assessment.

In conclusion, with considerable national attention focused on providing patient-centered care, this project demonstrates the feasibility of obtaining highly reliable measures of patients' experiences with individual physicians and practices. Physician-specific samples were created by pooling sample across multiple payers, and with samples of 45 completed surveys per physician, highly reliable indicators of patients' experiences were established. The finding that individual physicians and sites account for the majority of system-related variance indicates the appropriateness of focusing on these levels for measuring and improving these dimensions of quality.

The importance of adding measures of patients' experiences of care to our nation's portfolio of quality measures is underscored by recent evidence that we are losing ground in these areas.46,47 The erosion of quality on those dimensions stands in sharp contrast to recent improvements noted in the technical quality of care.48–50 The improvements in technical quality, seemingly spurred by the routine monitoring and reporting of performance on these measures, lend credence to the aphorism that “what gets measured gets attention.” With key methodological barriers to measuring patients' experiences with individual primary care physicians and practices addressed, it is time to add this balance and perspective to our nation's portfolio of quality measures.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Commonwealth Fund and the Robert Wood Johns Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge members of our National Advisory Committee, our Massachusetts steering committee, and our project officers (Anne-Marie Audet, M.D., Steven Shoenbaum, M.D., and Michael Rothman, Ph.D.) for their invaluable advise and guidance throughout the project period. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Paul Kallaur, Nina Smith and their project staff at the Centers for the Study of Services (CSS) their technical expertise and commitment to excellence in obtaining the data from the study sample. Finally, we thank Ira B. Wilson, M.D., M.S. for comments on an earlier draft and Jamie Belli for technical assistance in preparing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein AM, et al. Public release of performance data: a progress report from the front. JAMA. 2000;283:1884–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee TH, Meyer GS, Brennan TA, et al. A middle ground on public accountability. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2409–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb041193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty-First Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon LS, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, Cleary PD, et al. Variation in patient-reported quality among health care organizations. Health Care Fin Rev. 2002;23:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cleary PD, et al. A conceptual model of the effects of health care organizations on the quality of medical care. JAMA. 1998;279:1377–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez H, Glahn T, Rogers W, Chang H, Fanjiang G, Safran D. Evaluating patients' experiences with individual physicians: a randomized trial of mail, internet and interactive voice response (IVR) telephone administration of surveys. Med Care. 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196961.00933.8e. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36:728–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams VS, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS 1.0 survey measures. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37:22–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillman DA. Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method. New York: John Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler FJ, Jr, Gallagher PM, Stringfellow VL, Zaslavsky AM, Thompson JW, Cleary PD. Using telephone interviews to reduce nonresponse bias to mail surveys of health plan members. Med Care. 2002;40:190–200. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Cleary PD. Factors affecting response rates to the consumer assessment of health plans study survey. Med Care. 2002;40:485–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lasek RJ, Barkley W, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. An evaluation of the impact of nonresponse bias on patient satisfaction surveys. Med Care. 1997;35:646–52. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. NY: Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen HM, Rogers WH. The consumer health plan value survey: round two. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:156–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner H. Alternative approaches for estimating prevalence in epidemiologic surveys with two waves of respondents. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1236–45. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbert R, Bravo G, Korner-Bitensky N, Voyer L. Refusal and information bias associated with postal questionnaires and face-to-face interviews in very elderly subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:373–81. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keeter S, Miller C, Kohut A, Groves RM, Presser S. Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a national telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2000;64:125–48. doi: 10.1086/317759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasquet I, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Impact of reminders and method of questionnaire distribution on patient response to mail-back satisfaction survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1174–80. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman EM, Clusen NA, Hartzell M. Better Late? Characteristics of Late Responders to a Health Care Survey. No. PP03-52, 1–7. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunnelly J, Bernstein I. Psychometric Theory. 3rd. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User's Guide. Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, Beaulieu ND, Cleary PD. How consumer assessments of managed care vary within and among markets. Inquiry. 2000;37:146–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer TP, Hayward RA, Greenfield S, Wagner EH, Kaplan SH, Manning WG. The unreliability of individual physician “report cards” for assessing the costs and quality of care of a chronic disease. JAMA. 1999;281:2098–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landon BE, Normand SL, Blumenthal D, Daley J. Physician clinical performance assessment: prospects and barriers. JAMA. 2003;290:1183–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller ME, Hui SL, Tierney WM, McDonald CJ. Estimating physician costliness. An empirical Bayes approach. Med Care. 1993;31:YS16–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199305001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orav EJ, Wright EA, Palmer RH, Hargraves JL. Issues of variability and bias affecting multisite measurement of quality of care. Med Care. 1996;34:SS87–101. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayward RA, Manning WG, Jr, McMahon LF, Jr, Bernard AM. Do attending or resident physician practice styles account for variations in hospital resource use? Med Care. 1994;32:788–94. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiMatteo MR. Enhancing patient adherence to medical recommendations. JAMA. 1994;271:79–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD. Physicians' characteristics influence patients' adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication: patients' response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196903062801004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson IB, Rogers WH, Chang H, Safran DG. Cost-related skipping of medications and other treatments among Medicare beneficiaries between 1998 and 2000: results of a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:715–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JEJ, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review [see comments] CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians' interviewing skills and reducing patients' emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safran DG, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Murphy J, Rogers WH. Switching doctors: predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician's practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:130–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull V, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice: lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hickson GBC, Clayton EW, Entman SS, et al. Obstetrician's prior malpractice experience and patients' satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994;272:1583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller S. American Board of Medical Specialties; Implementing the CAHPS Ambulatory Care Survey: A Panel Discussion of Current and Planned Activities. CAHPS Across the Health Care Continuum: 9th National User Group Meeting; 12-2-2004; Baltimore, MD. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karp M. Massachusetts Health Quality Partners; Implementing the CAHPS Ambulatory Care Survey: A Panel Discussion of Current and Planned Activities. CAHPS Across the Health Care Continuum: 9th National User Group Meeting; 12-2-2004; Baltimore, MD. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damberg C. Pacific Business Group on Health; Implementing the CAHPS Ambulatory Care Survey: A Panel Discussion of Current and Planned Activities. CAHPS Across the Health Care Continuum: 9th National User Group Meeting; 12-2-2004; Baltimore, MD. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) CMS Doctor's Office Quality Project Overview, 7-15-2004 http://www.cms.hhs.gov/quality/doq/DOQOverview.pdf.

- 46.Safran DG. Defining the future of primary care: what can we learn from patients? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:248–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy J, Chang H, Montgomery J, Rogers WH, Safran DG. The quality of physician-patient relationships: patients' experiences 1996–1999. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Committee for Quality Assurance. State of Managed Care Quality 2000. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Committee for Quality Assurance. State of Managed Care Quality, 2001. Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jencks SF, Huff ED, Cuerdon T. Change in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–1999 to 2000–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:305–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]