Abstract

BACKGROUND

Providing and eliciting high-quality feedback is valuable in medical education. Medical learners' attainment of clinical competence and professional growth can be facilitated by reliable feedback. This study's primary objective was to identify characteristics that are associated with physician teachers' proficiency with feedback.

METHODS

A cohort of 363 physicians, who were either past participants of the Johns Hopkins Faculty Development Program or members of a comparison group, were surveyed by mail in July 2002. Survey questions focused on personal characteristics, professional characteristics, teaching activities, self-assessed teaching proficiencies and behaviors, and scholarly activity. The feedback scale, a composite feedback variable, was developed using factor analysis. Logistic regression models were then used to determine which faculty characteristics were independently associated with scoring highly on a dichotomized version of the feedback scale.

RESULTS

Two hundred and ninety-nine physicians responded (82%) of whom 262 (88%) had taught medical learners in the prior 12 months. Factor analysis revealed that the 7 questions from the survey addressing feedback clustered together to form the “feedback scale” (Cronbach's α: 0.76). Six items, representing discrete faculty responses to survey questions, were independently associated with high feedback scores: (i) frequently attempting to detect and discuss the emotional responses of learners (odds ratio [OR] = 4.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2 to 9.6), (ii) proficiency in handling conflict (OR = 3.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 9.3), (iii) frequently asking learners what they desire from the teaching interaction (OR = 3.5, 95% CI 1.7 to 7.2), (iv) having written down or reviewed professional goals in the prior year (OR = 3.2, 95% CI 1.6 to 6.4), (v) frequently working with learners to establish mutually agreed upon goals, objectives, and ground rules (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.7), and (vi) frequently letting learners figure things out themselves, even if they struggle (OR = 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.9).

CONCLUSIONS

Beyond providing training in specific feedback skills, programs that want to improve feedback performance among their faculty may wish to promote the teaching behaviors and proficiencies that are associated with high feedback scores identified in this study.

Keywords: feedback, teaching skills, learner centeredness, medical education

Feedback, which is necessary for ensuring learning, is a process involving observation, problem-identification, providing information, goal development, and solution by trial and error.1–3 Feedback often serves as the impetus for performance improvement, and therefore is a fundamental component of teaching and learning.

In medical education, feedback to learners is an informed, nonevaluative appraisal of performance by the teacher.2 Its purpose is to both reinforce strengths and foster improvements in the learner.2 Feedback, when used correctly, provides the learner with insight into actions and consequences, highlighting the dissonance between the intended result and the actual result.4 Improved performances secondary to feedback have been demonstrated in clinical skills, such as heart and lung auscultation5–10 and diagnostic accuracy.11,12 Because medical learners gain limited insight into the strengths and weaknesses of their clinical skills without feedback, clinical medical education depends on high-quality feedback.13

Several empiric studies have found that medical students and residents are not satisfied with the quantity and quality of feedback that they receive from their physician teachers.13–17 In response, many faculty development programs and workshops were developed to enhance physicians' feedback skills,18,19 particularly of junior faculty members.20 In this study, we sought to develop a measure of feedback skill and then to identify characteristics of physician teachers that are associated with high levels of proficiency with feedback.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study of physicians who are part of our faculty development database to measure constructs related to their teaching behaviors, approaches, and self-assessed proficiencies.

Study Participants

The physicians in the database had either (i) participated in the Johns Hopkins Faculty Development Program (JHFDP) between 1987 and 2000 or (ii) had been named by a JHFDP participant as a control who was similar to the participant in terms of gender, age, and job description. The physicians' locations represented a wide geographic distribution.

Survey Development and Data Collection

A 15-page survey, developed to assess the long-term outcomes of the JHFDP, was mailed to 363 physicians in July 2002 after approval by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.21 Questions in the survey were organized into 7 different categories: personal and career characteristics; scholarship; education enjoyment; working with others; desirable teaching behaviors; teaching proficiency; learner-centeredness. Seven discrete questions in the survey asked about behaviors or self-assessed proficiencies related to providing, eliciting, or reflecting on feedback.21

Data Analysis

Only responses from active physician teachers (those who indicated that they had taught medical learners in the prior 12 months) were analyzed. For each question in the survey, we examined frequency of responses looking for irregularities in their distribution. For continuous variables, we checked distributions and descriptive statistics for evidence of skewness, outliers, and nonnormality. Nonparametric tests were used where appropriate. Categorical variables were recoded and analyzed as proportions.

All 7 questions in the survey, specifically addressing feedback, were subjected to factor analysis to assess them as candidates for a composite feedback measure, hereafter to be called the feedback scale. Before inclusion in the factor analysis, candidate questions were examined for sufficient response variation. We also assessed the mean sampling adequacy of each survey question for all respondents. We examined 2 rotations: Promax and Varimax. In an orthogonal rotation (Varimax), the factors are uncorrelated, whereas, in an oblique rotation (Promax), the factors are allowed to be correlated in order to maximize individual factor loading. We first examined a Scree plot to visually determine the number of factors with eigen values over 1. The 2 rotations similarly resulted in a single factor solution, the 7 items all clustered together. Cronbach's α was used to quantify the internal consistency of the factor. Item to total correlations were examined to assess the extent to which each item contributed to the overall reliability of the factor. The deletion of any single item caused the α to decrease, indicating the unique contribution of each of the 7 questions to the overall α, thereby strengthening the internal reliability.

We initially collapsed the feedback scale into 3 categories—low, medium, high. Attributes of the physician respondents were then compared in bivariate analysis with the 3 categories using cross tabulations and χ2. In looking at the data in different ways, the results were similar when the feedback scale dichotomized at the median and when the scale was analyzed as a continuous variable. For ease of presentation, the data are presented using “high” versus “low” feedback scorers. Logistic regression was used to produce unadjusted odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) to characterize the association of individual attributes with the likelihood of being a “feedback high scorer.”

Multivariable logistic-regression models were then used to identify independent associations between individual variables and “high” versus “low” feedback scorers. In the first stage, we constructed 7 domain-specific multivariate models corresponding to each area of inquiry in the questionnaire. These models consisted only of variables that were associated with the dependent variable (high feedback score) in the bivariate analysis at P<.1. Variables included in the models were checked for collinearity. In the second stage, variables that were significantly associated with feedback status in the domain-specific models were included in a study-wide multivariable model. In all model building, we applied a user-defined stepwise approach evaluating the change in model χ2 with the addition of each variable. To assess the goodness of fit, we applied the Hosmer-Lemeshow method based on deciles of risk.22 Data were analyzed using STATA 8.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Response Rate and Characteristics of Respondents

Surveys were completed by 299 of 363 physicians contacted, for a response rate of 82%. There was no difference between responders and nonresponders for gender (P = .79) and a small difference in mean age (42.3 vs 41.6 years, P = .001). Among the 299 respondents, 262 (88%) had taught medical learners during the 12 months before being surveyed. Characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 262 Responding Physicians

| Respondents(N = 262)* | |

| Demographics | |

| Male, n (%) | 155 (61) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42 (6) |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 208 (84) |

| Living with spouse/significant other, n (%) | 207 (84) |

| Professional characteristics | |

| Past participation in Johns Hopkins FDP, n (%) | 178 (68) |

| General internal medicine/Geriatrics, n (%) | 197 (82) |

| Currently has a medical school faculty appointment, n (%) | 207 (82) |

| Instructor/Assistant Professor, n (%) | 147 (56) |

| Total work hours by percentage in the past year | |

| Clinical effort, mean % (SD) | 49 (31) |

| Teaching, mean % (SD) | 16 (15) |

| Research, mean % (SD) | 15 (24) |

| Non-educational administration, mean % (SD) | 10 (19) |

| Educational program development, mean % (SD) | 6 (11) |

| Taught medical students in past year, n (%) | 206 (81) |

| Taught residents in past year, n (%) | 210 (83) |

| Scholarly activity | |

| Ever authored a scholarly publication, n (%) | 195 (77) |

| Ever authored a scholarly publication on education, n (%) | 70 (28) |

Numbers may not total actual percentage due to item nonresponse

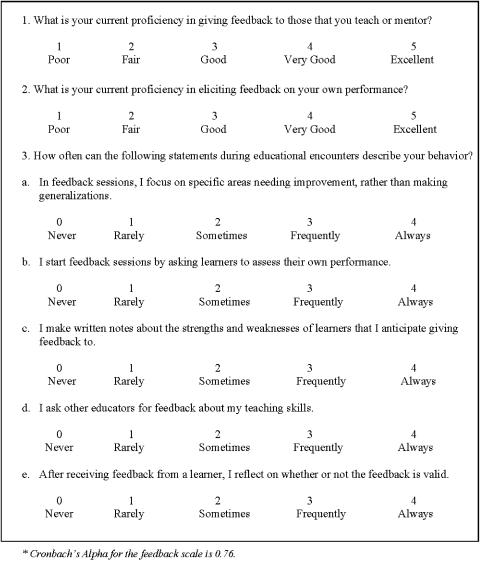

Feedback Scale

Factor analysis included all 7 questions from the survey wherein respondents assessed themselves with respect to feedback behaviors and self-assessed proficiency. The answers to all 7 feedback-related questions clustered together to form a single factor, herein referred to as the “feedback scale.” No variables were eliminated based on poor factor loadings. The Cronbach's α for the feedback scale was 0.76, suggesting that the internal reliability of the factor analysis is acceptable23 (Table 2). On the feedback scale, presented in Figure 1, the lowest possible score is 2 and the highest is 30. Of the 262 active physician teachers, 254 completed all 7 questions that comprise the scale. The scale's median score was 19 with a range of 8 to 30. In dividing the physician cohort by the feedback scale, 136 physicians (53%) were designated as “low” scorers, because they scored equal to or below the median, and 118 (47%) were classified as “high” scorers, because their scores were greater than the median value.

Table 2.

Responding Teaching Physicians' Assessments of Themselves with Respect to the 7 Questions from the Survey Instrument Related to Feedback (n = 254)*

| Areas of Physician Self-Assessment | Factor Analysis† | Mean ± SD | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor: feedback scale | 0.76 | ||

| Proficiency in giving feedback to those you teach or mentor‡ | 0.79 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | |

| Frequency of focusing on specific areas needing improvement, rather than making generalizations, during feedback sessions§ | 0.71 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | |

| Proficiency in eliciting feedback on your own performance‡ | 0.70 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | |

| Frequency of starting feedback sessions with medical learners by asking them to assess their own performance§ | 0.69 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Frequency of writing notes about strengths and weaknesses of learners for whom you will give feedback§ | 0.55 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Frequency of asking other educators for feedback about one's teaching skills§ | 0.52 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | |

| Frequency of reflecting about the validity of feedback that is received from learners§ | 0.50 | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

The self-assessments from 8 physician teachers were not included in the factor analysis because they failed to answer all 7 questions

Varimax rotation factor loading values for each item is listed.

The mean score for each item was derived from a question that asked the physician teachers to assess their own proficiency in select areas with a 5-point Likert scale (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent).

The mean score for each item was derived from a question that asked about how frequently they performed specific behaviors with a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always)

FIGURE 1.

The feedback scale: questions from the survey instrument that emerged from factor analysis to form the scale.*

Differences Between Physician Teachers by Scores on the Feedback Scale

The teaching physicians' responses to questions within each of the 7 domains of the survey (personal and career characteristics, scholarship, education enjoyment, working with others, desirable teaching behaviors, teaching proficiency, and learner-centeredness) were significantly different in bivariate analysis based upon their classification as “high” versus “low” on the feedback scale (Table 3). Within each of the 7 domains of inquiry, 4 to 12 variables were significantly different between the high scorers and the low scorers on the feedback scale. The 2 questions that appeared to be the most strongly associated with being a high-scorer on the feedback scale were having a high proficiency in leading others (OR = 13.2, 95% CI 3.1 to 57.0) and frequently ensuring that respect is conveyed to all participants when leading small groups (OR = 11.1, 95% CI 1.4 to 86.7).

Table 3.

After Categorizing 262 Responding Physicians into “High” or “Low” Scorers on the Feedback Scale, Odds Ratios Demonstrating Associations with Being a High Scorer

| Characteristic* | Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Being a High Scorer†(95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Personal and career characteristics | |

| Non-Caucasian (vs non-Hispanic white) | 2.00 (1.01 to 4.00) |

| Feels present job has “a lot” of opportunity to work as part of a team (vs moderate amount or less) | 2.10 (1.27 to 3.48) |

| Teaching >10% total work hours in past year (vs less than 10%) | 2.30 (1.38 to 3.82) |

| Director/Associate Director of residency program (vs not) | 2.32 (1.23 to 4.36) |

| Director/Associate Director of medical education course or clerkship (vs not) | 2.44 (1.46 to 4.08) |

| Taught or mentored in FDP/workshop in past year (vs not) | 2.48 (1.48 to 4.15) |

| Values or priorities written or reviewed in last year (vs not) | 2.55 (1.52 to 4.27) |

| Ever FDP developer or facilitator (vs not) | 2.75 (1.54 to 4.90) |

| Taught or mentored housestaff or medical students in morning or noon conference in past year (vs not) | 3.14 (1.58 to 6.26) |

| Developed or implemented curricula in last 5 years (vs not) | 3.14 (1.78 to 5.55) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” recognize own areas of weakness and use it as an opportunity for gth (vs less) | 3.23 (1.83 to 5.69) |

| Professional/work goals written or reviewed in the last year (vs not) | 3.82 (2.15 to 6.78) |

| Scholarship | |

| Ever received local or regional teaching or education award (vs not) | 1.91 (1.15 to 3.17) |

| Ever participated in national/regional meeting as presenter (vs not) | 2.04 (1.04 to 4.02) |

| External funds for educational curriculum development, administration, or evaluation in past 2 y (vs not) | 2.06 (1.07 to 3.96) |

| Faculty rank at or above Associate Professor (vs below) | 2.15 (1.16 to 3.98) |

| Ever gave an oral presentation related to education at a national/regional meeting (vs not) | 2.72 (1.51 to 4.89) |

| External funds for teaching in past 2 y (vs not) | 3.56 (1.34 to 9.44) |

| Education enjoyment | |

| Enjoys giving lectures and presentations (vs does not) | 2.10 (1.24 to 3.56) |

| Enjoys one-on-one teaching or precepting (vs does not) | 2.15 (1.25 to 3.70) |

| Enjoys leading small groups (vs does not) | 2.76 (1.63 to 4.67) |

| Enjoys mentoring (vs does not) | 2.92 (1.71 to 4.98) |

| Working with others | |

| “Agree” or “strongly agree” that I like to do most things myself, rather than delegate to others (vs disagree) | 0.56 (0.34 to 0.93) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” seek opportunities to work on projects with others (vs less) | 2.44 (1.44 to 4.13) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” pay attention to others' needs (vs less) | 2.61 (1.11 to 6.10) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” elicit input from those who might be affected by my decisions (vs less) | 2.78 (1.25 to 6.22) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” draw in those who don't participate much when leading small groups (vs less) | 3.40 (1.79 to 6.43) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” help the small groups that I lead meet their goals for any given meeting (vs less) | 4.62 (2.11 to 10.10) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” ensure that respect is conveyed to all participants when leading small groups (vs less) | 11.08 (1.42 to 86.67) |

| Desirable teaching behaviors | |

| “Always” or “Frequently” spend time building supportive relationships with my learners (vs less) | 2.20 (1.23 to 4.29) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” let learners know how different situations make me feel (vs less) | 2.48 (1.49 to 4.14) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” let learners know my limitations as a teacher (vs less) | 2.71 (1.61 to 4.56) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” help learners identify resources to meet their learning needs (vs less) | 2.78 (1.42 to 5.45) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” let learners figure things out by themselves, even if they struggle (vs less) | 2.94 (1.76 to 4.91) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” assess whether my actions as a teacher correspond with my values (vs less) | 2.95 (1.73 to 5.03) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” challenge learners to consider alternative management approaches when precepting or teaching one-on-one (vs less) | 2.98 (1.49 to 5.96) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” express concern and support for my learners when they struggle (vs less) | 3.57 (1.72 to 7.41) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” attempt to detect and discuss emotional responses of my learners (vs less) | 6.09 (3.22 to 11.55) |

| Teaching proficiency | |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in mentoring others (vs less) | 2.17 (1.02 to 4.63) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in role modeling for medical learners (vs less) | 2.74 (1.04 to 7.19) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in giving lectures or presentations (vs less) | 3.28 (1.42 to 7.57) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in handling conflict (vs less) | 3.77 (1.71 to 8.27) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in leading small groups (vs less) | 4.34 (1.82 to 10.33) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in overall teaching skills (vs less) | 7.86 (1.77 to 34.97) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in leading others (vs less) | 13.19 (3.05 to 57.04) |

| Learner-centeredness | |

| “Always” or “Frequently” conduct a formal needs assessment, like survey or focus group, etc, when planning curriculum (vs less) | 2.72 (1.38 to 5.38) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” adapt learning plan to their need (vs less) | 3.04 (1.66 to 5.56) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” use different educational strategies based upon learning objectives and learners' needs when planning curriculum (vs less) | 3.79 (1.74 to 8.26) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” assess and focus on learners' needs rather than mine when precepting or teaching one-on-one (vs less) | 4.46 (2.37 to 8.41) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” work to establish mutually agreed-upon goals, objectives, and ground rules with learners (vs less) | 4.98 (2.75 to 9.04) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” ask learners what they desire from our interaction (vs less) | 6.04 (3.33 to 10.95) |

These 7 categories correspond to areas of inquiry in the questionnaire

By comparing the responses of the low scorers (≤19; those below the median) and the high scorers (>19; those above the median), factors were identified that were associated with being a high scorer on the feedback scale

Adjustment for all significant variables within the 7 domains using multivariate analysis identified several independent predictors of high scores on the feedback scale (Table 4). The 6 physician teacher characteristics independently associated with high feedback scores were (i) frequently attempting to detect and discuss the emotional responses of learners, (ii) proficiency in handling conflict, (iii) frequently asking learners what they desire from the teaching interaction, (iv) having written down or reviewed professional goals in the prior year, (v) frequently working with learners to establish mutually agreed upon goals, objectives, and ground rules, and (vi) frequently letting learners figure things out themselves, even if they have to struggle.

Table 4.

Independent Associations of Characteristics of Responding Physicians with Being a High Scorer on the ‘Feedback Scale’ (n = 262)

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratios for Being a High Scorer* (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| “Always” or “Frequently” let learners figure things out by themselves, even if they struggle (vs less) | 2.08 (1.11 to 3.92) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” work to establish mutually agreed-upon goals, objectives, and ground rules with learners (vs less) | 2.23 (1.07 to 4.65) |

| Professional/work goals written or reviewed in the last year (vs not) | 3.21 (1.62 to 6.35) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” ask learners what they desire from our interaction (vs less) | 3.51 (1.72 to 7.16) |

| Current proficiency “very good” or “excellent” in handling conflict (vs less) | 3.72 (1.48 to 9.31) |

| “Always” or “Frequently” attempt to detect and discuss emotional responses of my learners (vs less) | 4.55 (2.15 to 9.59) |

Variables that were significantly associated (P<.05) with feedback (high vs low) were included into this multivariable model

DISCUSSION

In 1983, Dr. Jack Ende reviewed the feedback protocols used in other professions (including business administration, psychology, and education) and proposed recommendations and models for use in medical education.2,24 These guidelines have helped educators to better understand feedback and to more effectively apply these paradigms to clinical settings.2,13,24–28 Nevertheless, providing feedback encompasses a complex skill set, and gaining proficiency with feedback remains a challenge for medical educators.15,28,29 The ability to deliver feedback that is accurate, specific, and timely is a fundamental teaching skill for medical educators.2,29,30 Feedback facilitates learning and can serve as a stimulus for reflective practice and professional growth.31 Feedback from individuals that we respect and trust can reinforce what we are doing well and may encourage change in areas where improvement is needed.29,32–34 Without constructive feedback, medical learning is incomplete and clinical competence may not be realized.4,13,34 This study of physician teachers adds to the empiric work in this area through the creation of a scale related to feedback, such that factors associated with higher levels of proficiency with feedback have been identified.

Two of the 6 variables that were independently associated with scoring highly on the feedback scale are integral components of learner centeredness. Learner centeredness includes behaviors that demonstrate a teacher's respect for learners' capacity to (i) identify their own goals and (ii) actively participate in their own learning.32,35–37 Learner-centered educators are believed to be more confident, experienced teachers who are genuinely committed to the needs of their learners.29,33,38,39 It makes sense that learner-centered physician teachers are better at giving and eliciting feedback. Many faculty development programs dedicated to improving participants' teaching focus on helping physicians more comprehensively understand learners' needs as a first step before embarking on specific teaching skills.32

Three of the 7 items in the feedback scale relate to a teacher's ability to elicit feedback about their own performance. We hypothesized that the 4 questions related to delivering feedback would group into 1 factor and the 3 concerning eliciting feedback would come together as a separate factor. This did not occur; the 7 questions clustered together to form a single factor solution, the feedback scale. Thayer's book, 50 Strategies for Experiential Learning, illustrates that the principles and skills for receiving feedback are almost the same as those for giving feedback.40 As such, the result of our factor analysis resulting in a single factor is not terribly surprising. It is our belief that teachers who are active and interested in eliciting and using feedback for their own development will likely be similarly engaged in providing feedback to learners.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, we relied exclusively on self-assessment and self-report to characterize the respondents. Second, like all cross-sectional studies, our results describe associations between various factors and high levels of feedback skill but causality cannot be determined. Third, the feedback scale was developed from a selected group of questions related to feedback that were included in a questionnaire assessing numerous outcomes for a faculty development program. It lacks established predictive validity and there is no gold standard for assessing criterion-related validity. Nevertheless, the scale does have some face and content validity in that only variables that (i) addressed fundamental elements of feedback and (ii) were found to be relevant from prior research in this field,2,24–28 were entered into the modeling. The differences in theoretically related variables between respondents who scored above and below the median on the feedback scale are a measure of the scale's “construct” validity. Further, factor analysis and Cronbach's α established the scale's uni-dimensionality and internal reliability. Finally, because many of the respondents (68%) had been trained in the JHFDP, the results in this study may not be generalizable to all other physician teachers. In looking at the responses to the 7 questions that make up the feedback scale, only 2 were significantly different between JHFDP participants and nonparticipants (items 1 and 3b in Fig. 1). Nonetheless, physician teachers who had participated in the JHFDP were more likely to be high scorers on the feedback scale (P<.05).

We believe that proficiency in feedback skills promotes efficient and effective learning in medicine. High-quality feedback is not only what medical learners desire13,14,41 but what they associate with high-quality teaching.42 This paper extends our knowledge about feedback in medical education by identifying teaching behaviors and proficiencies associated with providing, eliciting, and reflecting on feedback. Programs that want to improve feedback performance among their faculty may want to promote these associated behaviors and proficiencies, in addition to providing training in specific feedback skills.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright is an Arnold P. Gold Foundation Associate Professor of Medicine. The authors are indebted to Dr. L. Randol Barker, Dr. David Kern, Ms. Cheri Smith, and Ms. Darilyn Rohlfing for their assistance.

Financial Support: The Johns Hopkins Faculty Development Program in Teaching Skills is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Grant #5 D55HP00049-05-00.

REFERENCES

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. [February 22, 2004]; Available at http://www.britannica.com.

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorn MH. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky; 2001. Expanding the Envelope: Flight Research at NACA and NASA. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler DA. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc; 1977. Feedback and Organization Development: Using Data-Based Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79(suppl 10):S70–S81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley RS, Naus GJ, Stewart J, Friedman CP. Development of visual diagnostic expertise in pathology: an information-processing study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:39–51. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiszny JA. Teaching cardiac auscultation using simulated heart sounds and small group discussion. Fam Med. 2001;33:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, McGaghie WC, et al. Effectiveness of computer-based system to teach bedside cardiology. Acad Med. 1999;74(suppl 10):S93–S5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, McGaghie WC, et al. Effectiveness of a cardiology review course for internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14:223–8. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1404_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire C, Hurley RE, Babbott D, Butterworth JS. Auscultatory skill: gain and retention after intensive instruction. J Med Educ. 1964;39:120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigton RS, Patil KD, Hoellerich VL. The effect of feedback in learning clinical diagnosis. Acad Med. 1986;61:816–22. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Griffin T. Comparing different types of performance feedback and computer-based instruction in teaching medical students how to diagnose acute abdominal pain. Acad Med. 1993;68:862–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ende J. The evaluation product: putting it to use. In: Lloyd JS, Langsley DG, editors. How to Evaluate Residents. Chicago: American Board of Medical Specialties; 1986. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Corley JB. Lexingon, MA: The Collamore Press; 1983. Evaluating Residency Training. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan JR, Bellini LM, Shea JA. Have you had your feedback today? Acad Med. 2000;75:1041. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil DH, Heins M, Jones PB. Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. J Med Educ. 1984;59:856–64. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LS, Gruppen LD, Alexander GL, Fantone JC, Davis WK. A predictive model of student satisfaction with the medical school learning environment. Acad Med. 1997;72:134–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199702000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:205–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole KA, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Williamson PR, Wright SM, Kern DE. Faculty development in teaching skills: an intensive longitudinal model. Acad Med. 79:469–80. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Mygdal WK, et al. Clinical teaching improvement: past and future for faculty development. Fam Med. 1997;29:252–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight AM, Cole KA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Long-term follow up of a longitudinal faculty development program in teaching skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:721–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. New York: Wiley; 1989. Applied Logistic Regression. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnaly J. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. Psychometric Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Kravas CF, Kravas KJ. Effective feedback principles sheet. In: Thayer L, editor. 50 Strategies for Experiential Learning: Book One. San Diego: University Associates Inc; 1976. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace L. Supervisory Management; Non-evaluative approaches to performance appraisals; pp. 97–101. MAR 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feins A, Waterman MA, Peters AS, Kim M. The teaching matrix: a tool for organizing teaching and promoting professional growth. Acad Med. 1996;71:1200–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlander JD, Bor DH, Strunin L. A structured clinical feedback exercise as learning-to-teach practicum for medical residents. Acad Med. 1994;69:18–20. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter L. NTL Reading Book for Human Relations Training. NTL Institute; 1982; Giving and Receiving Feedback; It Will Never Be Easy, But It Can Be Better. Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg J, Jason H. Boulder, CO: Center for Instructional Support, Johnson Printing; 1991. Providing Constructive Feedback: A CIS Guide Book for Health Profession Teachers. [Google Scholar]

- Kern DE, Wright SM, Carrese JA, et al. Personal growth in medical faculty: a qualitative study. West J Med. 2001;175:98. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.2.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson L, Irby DM. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73:387–96. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irby DM, Gillmore GM, Ramsey PG. Factors affecting ratings of clinical teachers by medical students and residents. J Med Educ. 1987;62:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson P, Ferguson-Smith AC, Johnson MH. Developing essential professsional skills: a framework for teaching and learning about feedback. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludmerer KM. Learner-centered medical education. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1163–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderman RB, Williamson KB, Frank M, Heitkamp DE, Kipfer HD. Learner-centered education. Radiology. 2003;227:15–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2271021124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpaw TM, Wolpaw DR, Papp KK. Snapps: a learner-centered model for outpatient education. Acad Med. 2003;78:893–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200309000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky LE, Monson D, Irby DM. How excellent teachers are made: reflecting on success to improve teaching. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1998;3:207–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1009749323352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky LE, Irby DM. If at first you don't succeed: using failure to improve teaching. Acad Med. 1997;72:973–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer L. San Diego, CA: University Associates Inc; 1976. 50 Strategies for Experiential Learning: Book One. [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. Regular feedback holds the key to improving house staff performance. Careers Intern Med. 1985;1:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Torre DM, Sebastian JL, Simpson DE. Learning activities and high-quality teaching: perceptions of third-year IM clerkship students. Acad Med. 2003;78:812–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]