Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Following the Institute of Medicine report “To Err is Human,” the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality identified proper central venous catheter (CVC) insertion techniques and wide sterile barriers (WSB) as 2 major quality indicators for patient safety. However, no standard currently exists to teach proper procedural techniques to physicians.

AIM

To determine whether our nonhuman tissue model is an effective tool for teaching physicians proper wide sterile barrier technique, ultrasound guidance for CVC placement, and sharps safety.

PARTICIPANTS

Educational sessions were organized for physicians at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Participants had a hands-on opportunity to practice procedural skills using a nonhuman tissue model, under the direct supervision of experienced proceduralists.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

An anonymous survey was distributed to participants both before and after training, measuring their reactions to all aspects of the educational sessions relative to their prior experience level.

DISCUSSION

The sessions were rated highly worthwhile, and statistically significant improvements were seen in comfort levels with ultrasound-guided vascular access and WSB (P<.001). Given the revitalized importance of patient safety and the emphasis on reducing medical errors, further studies on the utility of nonhuman tissue models for procedural training should be enthusiastically pursued.

Keywords: medical education, ultrasound, patient safety, procedures, wide sterile barriers, vascular access.

Following the widely distributed 1999 Institute of Medicine report “To Err is Human,” the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) identified the implementation of proper central venous catheter (CVC) insertion techniques and the use of wide sterile barriers (WSB) as 2 major quality indicators for patient safety.1,2 These guidelines also delineated the evidence supporting the use of ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion as a means to reduce the number of placement failures, complications, and attempted venipunctures before successful placement.3 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality leans heavily in favor of the use of WSB and ultrasound for CVC placement, assuming adequate training is provided.4

Although the AHRQ guidelines are relatively new, the requirement that physicians-in-training be certified in the performance of invasive procedures has existed for over a decade. The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) requires residents to successfully complete a set number of specific procedures in order to sit for the ABIM certification examination.5 Despite this requirement, surveys of residents and program directors consistently reveal that residents possess an inadequate comfort level for several invasive procedures at the end of their training.6–9 Once in clinical practice, procedural proficiency continues to be a valuable skill for physicians, even though after residency neither recertification nor review of procedural techniques are mandated.10,11 This may, in part, explain recent data suggesting that physicians are performing fewer procedures today than ever before.12

Given the apparent gap between regulatory expectations and actual performance, it is surprising that nonhuman models are not being more widely utilized for teaching procedural techniques. Attempts to standardize procedural training have occasionally been implemented,13 but current training methods for residents generally involves cadaver labs, synthetic models, and/or direct supervision in controlled settings such as the operating room.14,15 These venues, however, are largely inaccessible to internists, they can quickly become cost-prohibitive, and they do not necessarily address patient safety or bioethical concerns. Models that do exist for procedural training are either extremely costly or are not ultrasound friendly.16,17 Therefore, the predominant setting for residents to learn procedural techniques is the actual patient care arena. Trainees rely on their supervising residents or attending physicians for training, despite the varying quality of supervision and the lack of efficacy inherent in the “see one, do one” approach.15,18 Patients thus become unsuspecting subjects for procedure—naïve trainees who may not be familiar with the contents of the procedure kits or comfortable handling the equipment. With patients' safety at stake, and with a renewed emphasis on reducing medical errors, well-known complications such as vessel damage, pneumothorax, local hematoma, retroperitoneal bleeding, AV fistula formation, infections, and needle sticks to the operator should be deemed to be unacceptably high costs of learning.19–21

An ideal model for procedural training would be identical in feel and accuracy to the actual patient, allow for multiple attempts, be available and affordable, and result in improved patient safety. Therefore, we have embarked upon a multi-phase initiative, named the Procedural Patient Safety Initiative (PPSI), with the goal of improving patient safety related to commonly performed procedures. Phase I of this initiative involves designing a nonhuman tissue model on which invasive procedural techniques can be practiced. In order to validate this model as a useful training tool, we organized a series of educational sessions, staffed by experienced proceduralists who worked with participants in a 1:4 ratio, and taught medical professionals proper procedural and ultrasound techniques. The aim of this paper is to validate our tissue model as means for teaching vascular access techniques, the use of ultrasound, and WSB.

SETTING AND PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center is an 800-bed nonprofit hospital in Los Angeles, CA. The Division of General Internal Medicine operates a “Procedure Center,” which is staffed by internists and intensivists (i.e., proceduralists) who specialize in using ultrasound guidance and WSB for commonly performed procedures.22 These procedures include the placement of CVCs, dialysis catheters, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC), ports, as well as thoracenteses and paracenteses. During the course of the 2003 to 2004 academic year, the Procedure Center organized several educational sessions for medical professionals at Cedars-Sinai. Participation in the sessions was mandatory for all internal medicine and medicine/pediatric trainees, and was also open for attending physicians from all specialties. The completion of an anonymous survey was completely optional. Permission to conduct the survey was granted via a waiver by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical Center.

Each session began with a brief introductory lecture, including an orientation to the use of ultrasound and a demonstration of normal human vascular anatomy using ultrasound visualization on a volunteer. After the introduction, participants were given an opportunity to complete the first page of a survey related to their central line placement experience and familiarity with the use of ultrasound (available online). Participants were then divided into groups of 4 and assigned a workstation. Each station was staffed by a proceduralist and contained all materials necessary for WSB and central line insertion, a Sonosite 180 ultrasound (Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA), a sharps container, and a tissue model.

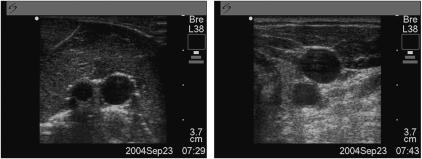

The tissue models were constructed from whole chickens, purchased from a local grocery store, into which we inserted 0.2 mm thickness rubber tubing that ran lengthwise through the chicken. Each length of tubing, or “vessel,” was sealed at both ends and filled with pressurized, colored tap water to simulate blood (Figs. 1 and 2). The chickens were discarded after each session. The total cost per model was $20.

Figure 1.

Nonhuman tissue model for procedural training.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound images of tissue model and human volunteer. Left image: simulated vessel in tissue model. Right image: carotid artery and internal jugular vein in a human volunteer.

Over the course of approximately 1 hour, each participant was systematically trained with the following educational goals in mind: (1) To practice visualizing structures using ultrasound and to cannulate the simulated vessels under direct ultrasound guidance; (2) to achieve competence in creating and maintaining a wide sterile barrier, including a review of proper gowning and gloving techniques, how to use fenestrated and wide sterile drapes, and the application of a sterile ultrasound probe sleeve; and (3) to learn techniques associated with proper sharps safety (ensuring that all sharps are kept off the field, handing sharps to assistants by the handle-side, and correct sharps disposal). Upon completion of the training session, participants had the option of completing the second page of the survey. A rank sum test was performed on the data using SPSS 12.0.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Overall, 136 individuals participated in the vascular access educational sessions, and 126 (93%) data collection forms were returned (Table 1). The majority (92%) of participants were interns and residents (“trainees”) in the internal medicine training program, while 8% of participants were attending physicians from the fields of cardiology, emergency medicine, and internal medicine. Procedural experience varied widely among the participants; most trainees (61%) had placed 5 or fewer CVCs, while the majority of attending physicians (80%) reported placing greater than 50 CVCs. Not unexpectedly, only 25% of the participants had ever used ultrasound guidance for central line placement and only 4% of participants use ultrasound consistently.

Table 1.

Demographics and Background Experience

| Trainees* | Attending Physicians* | Overall* | |

| Participants | 116 | 10 | 126 |

| Men | 59 (50.9%) | 6 (60%) | 65 (51.6%) |

| Women | 57 (49.1%) | 4 (40%) | 61 (48.4%) |

| Training level | |||

| Attending physicians | N/A | 10 | 10 (7.9%) |

| Fellows | 6 (5.2%) | N/A | 6 (4.8%) |

| Third-year residents | 13 (11.2%) | N/A | 13 (10.3%) |

| Second-year residents | 31 (26.7%) | N/A | 31 (24.6%) |

| First-year residents | 61 (52.6%) | N/A | 61 (48.4%) |

| Medical students | 4 (3.4%) | N/A | 4 (3.2%) |

| Registered nurse | 1 (0.8%) | N/A | 1 (0.8%) |

| Prior # of lines placed | |||

| 0 to 1 | 40 (34.5%) | 0 | 40 (31.7%) |

| 2 to 5 | 31 (26.7%) | 1 (10%) | 32 (25.4%) |

| 6 to 10 | 17 (14.7%) | 0 | 17 (13.5%) |

| 10 to 50 | 26 (22.4%) | 1 (10%) | 27 (21.4%) |

| >50 | 2 (1.7%) | 8 (80%) | 10 (7.9%) |

| Prior use of U/S for CVC placement | |||

| Always use (5) | 5 (4.3%) | 0 | 5 (4.0%) |

| Sometimes use (2 to 4/5) | 24 (20.7%) | 3 (30%) | 27 (21.4%) |

| Never use (1/5) | 87 (75.0%) | 7 (10%) | 94 (74.6%) |

Calculations are rounded to the nearest 0.1%

U/S, ultrasound; CVC, central venous catheter; N/A, not applicable

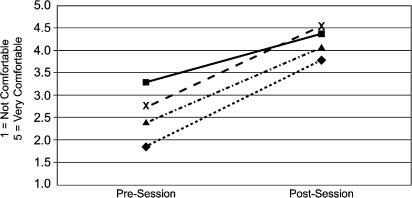

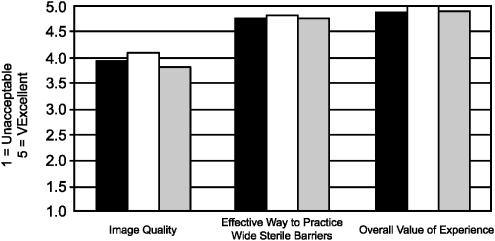

The survey results (using a 5–point scale) revealed that for trainees, mean precourse and postcourse comfort level with WSB increased from a baseline of 3.2 to 4.4 (P<.0001), and comfort level with the use of ultrasound for the placement of CVCs improved from 1.8 to 3.8 (P<.0001) (Fig. 3). Attending physicians' comfort level with WSB improved from a precourse value of 2.8 to 4.5 (P<.002), while their comfort level with the use of ultrasound for the placement of CVCs improved from 2.4 to 4.1 (P<.001) (Fig. 3). With regards to the utility of the tissue models, the image quality of the simulated vessels in the model was rated 3.8, the model effectiveness for practicing wide sterile barrier was rated 4.8, and the overall value of the educational session was rated 4.9 (Fig. 4), which was independent of the participant's level of training. Lastly, the value of the course as a way to reinforce sharps safety was rated 4.3, and no one objected to the use of chickens as the basis of the models.

Figure 3.

Comfort level with vascular access components. ◊/, ultrasound guidance—trainees; Δ/, ultrasound guidance—attendings; ▪/, wide sterile barriers—trainees; X/, wide sterile barriers— attendings (Po.002 for all categories).

Figure 4.

Reactions to tissue model. Black, trainees; white, attendings; gray, all participants

DISCUSSION

These educational sessions provided trainees and attending physicians with an inexpensive, low-stress, no-risk opportunity to practice vascular access techniques under ultrasound guidance, to learn the proper application of WSB, and to review sharps safety. The tissue models were constructed out of readily available materials at a nominal cost per device, and they were durable enough to allow several operators to gain experience in a single session. Overall, participants' experiences were highly favorable and their comfort levels improved significantly in all principal skill areas. We also found it significant that regardless of prior experience or level of training going into the session, participants found the experience to be highly worthwhile.

This is Phase I of a long-term strategy to improve patient safety. Our primary focus in this phase was to determine if we could validate a learner-accepted workshop that uses a nonhuman tissue model as the basis for procedural training. Consistent with this goal, this work has a number of distinct limitations. Most importantly, we did not measure actual learning or behavioral changes in the participants, nor did we track actual procedural complication rates before and after the sessions. Now that the model has been validated as a training tool, we plan to conduct training sessions with new participants and subsequently track complication rates and determine whether behaviors change and/or skills are applied in the clinical setting.

Another limitation inherent in this study relates to having provided large amounts of new information to participants in a short period of time. We recognize that our survey results may have been positively skewed due to the recency effect, and many of the skills taught may fade over time without reinforcement or subsequent practice opportunities. To address this, future sessions will include a written take-home summary of highlight points, a follow-up refresher course, and subsequent resurveying of participants. To measure the degree of the “use it or lose it” phenomenon, we will also document the time elapsed between an individual's training session and the application of skills taught on actual patients.

As portable ultrasound continues to gain wider acceptance and affordability over time, we believe it will become the standard of care for all vascular access procedures. We recognize that there are several barriers to more widespread ultrasound use. In addition to cost limitations and difficulties with access to equipment, a more intriguing barrier relates to experienced operators who, having trained with landmark techniques, are hesitant to learn a new approach. These physicians may resist abandoning their time-tested landmark techniques in order to overcome the learning curve inherent in adopting new technology. With regards to this issue, we found it significant that those participants who were already experienced in central line placement (primarily the attending physicians) also rated the experience as highly worthwhile, and they showed similar improvements in comfort level with the use of ultrasound. These preliminary data suggest the limiting factor in more rapid adaptation of newer, safer technology may simply have to do with an absence of available training, and prior research supports this theory.23 If subsequent research confirms that participation in training sessions actually leads to improved compliance and patient safety, training could be made available on a routine basis to all physicians who wish to stay current with emerging technology and adhere to patient safety guidelines. Furthermore, standardized training sessions could eventually be incorporated into a broader continuing medical education (CME) curriculum, with recertification in invasive procedures becoming a requirement similar to the 10-year ABIM board recertification requirement.

In conclusion, our nonhuman tissue models were widely accepted as an effective method for practicing procedural techniques without placing patients at risk. The ultimate goals, which will be evaluated in subsequent phases of the study, are to increase the use of ultrasound and WSB (2 widely recognized indicators of patient safety) when performing vascular access procedures, thus resulting in fewer procedural complications. Given the importance of patient safety and the heightened emphasis on reducing medical errors, we hope to contribute to a large-scale paradigm shift in medical education that will result in a significant change in the way in which physicians learn and practice procedural techniques.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Philip Ng, MD, Doran Kim, MD, Gregory Bierer, MD, and the staff of the Procedure Center for their assistance with the training sessions; Dani Hackner, MD, for statistical analysis; and Desdemona Stevenson-Sumner for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at www.blackwell-synergy.com

Procedures Society for Interns, Residents, Fellows, and Attendings

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1999. To Err is Human: Building A Safer Health System. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockville, MD: AHRQ Publication No. 01-E057. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices Summary. July 2001 http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/summary.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randolph AG, Cook DJ, Gonzales CA, Pribble CG. Ultrasound guidance for placement of central venous catheters: a meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:2053–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199612000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothschild JM. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 43. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD; Ultrasound guidance of central vein catheterization. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/chap21.htm AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058, July 2001: Chapter 21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Board of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine; 2004. Policies and Procedures for Certification, July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wigton RS. A method for selecting which procedural skills should be learned by internal medicine residents. J Med Educ. 1981;56:512–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wigton RS, Blank LL, Nicolas BA, Tape TG. Procedural skills training in internal medicine residencies: a survey of program directors. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:932–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hicks CM, Gonzales R, Morton MT, Gibbons RV, Wigton RS, Anderson RJ. Procedural experience and comfort level in internal medicine trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:716–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang GC, Smith CC, Gordon CE, Weingart SN. Residents' comfort performing inpatient medical procedures. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):162–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandel JH, Rich EC, Luxenberg MG, Spilane MT, Kern DC, Parrino TA. Preparation for practice in internal medicine. A study of ten years of residency graduates. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:853–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wigton RS, Nicolas JA, Blank LL. Procedural skills of the general internist. A survey of 2500 physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:1023–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-12-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wigton RS, Alguire PC. Procedural skills of the general internist 18 y later: a re-survey of ACP members. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:162. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith CC, Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, et al. Creation of an innovative inpatient medical procedure service and a method to evaluate house staff competency. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:510–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powers LR, Draeger SK. Using workshops to teach residents primary care procedures. Acad Med. 1992;67:743–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oxentenko AS, Ebbert JO, Ward LE, Pankratz VS, Wood KE. A multidimensional workshop using human cadavers to teach bedside procedures. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15:127–30. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eason MP, Goodrow MS, Gillespie JE. A device to stimulate central venous cannulation in the human patient simulator. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1245–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200311000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macnab AJ, Macnab M. Teaching pediatric procedures: the Vancouver model for instructing Seldinger's technique of central venous access via the femoral vein. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E8. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce NC. Evaluation of procedural skills of internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 1989;64:213–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198904000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansfield PF, Hohn DC, Fornage BD, Gregurich MA, Ota DM. Complications and failures of subclavian-vein catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1735–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412293312602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sznajder JI, Zveibi FR, Bitterman H, Weiner P, Bursztein S. Central vein catheterization. Failure and complication rates by three percutaneous approaches. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:259–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.146.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bold RJ, Wsinchester DJ, Madary AR, Gregurich MA, Mansfield PF. Prospective, randomized trial of Doppler assisted subclavian vein catheterization. Arch Surg. 1998;133:1089–93. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.10.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen BT, Ng PT, Ault MJ. The proceduralist: an emerging specialty for general internists. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:50–1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey RP, Ault M, Greengold NL, Rosendahl T, Cossman D. Ultrasonography performed by primary care residents for abdominal aortic aneurysm screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:845–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Procedures Society for Interns, Residents, Fellows, and Attendings