Abstract

Relationship-centered care (RCC) is a clinical philosophy that stresses partnership, careful attention to relational process, shared decision-making, and self-awareness. A new complexity-inspired theory of human interaction called complex responsive processes of relating (CRPR) offers strong theoretical confirmation for the principles and practices of RCC, and thus may be of interest to communications researchers and reflective practitioners. It points out the nonlinear nature of human interaction and accounts for the emergence of self-organizing patterns of meaning (e.g., themes or ideas) and patterns of relating (e.g., power relations). CRPR offers fresh new perspectives on the mind, self, communication, and organizations. For observers of interaction, it focuses attention on the nature of moment-to-moment relational process, the value of difference and diversity, and the importance of authentic and responsive participation, thus closely corresponding to and providing theoretical support for RCC.

Keywords: patient-centered care, complexity, relationship, communication research

In a landmark 1994 monograph, a distinguished group of researchers, educators, and practitioners asserted the fundamental importance of relationships in health care: relationships between patients and clinicians; among members of interdisciplinary health care teams; between the health care system and the community; and—especially noteworthy—the relationship of the clinician with her or himself.1 The concept that they introduced, relationship-centered care (RCC), represents the most recent step in a long-standing movement to advance humanism in medicine—to complement the objectivist and reductionistic approach of science-based practice with a sensitive and empathic approach to the patient's subjective or lived experience of illness.2 This was the agenda of RCC's immediate precursors, patient-centered care3,4 and the Biopsychosocial Model.5–7 RCC takes another step forward by calling attention to the personhood of the clinician as well as that of the patient. It also recognizes explicitly the emergent capacities of a partnership or team to do things together that the individuals could not do on their own. According to the advocates of RCC, the capacity to form effective relationships and capacity for self-reflection are essential to good clinical care, and should be developed as a part of medical education.

RCC is more an ideology than a theory. It offers a set of values and methods; it is a philosophy of and an approach to care. But while its central theme—that relationships are essential to good care—is supported by a growing body of research,8 it does not elucidate the nature of relationships or explain how they work. This lack of an explicit theoretical underpinning is also characteristic of most research in the field of health care relationships; it is only the occasional study that explicitly references its basis in a theory such as Psychoanalysis, Marxist Theory, Self-Determination Theory, Attachment Theory, or Game Theory. Nonetheless, I would contend that even in the absence of an explicit theoretical framework, in this field there is a common implicit “metatheory,” a set of assumptions that shape how we think about and study health care relationships. In this paper, I would like to examine this implicit theoretical foundation, and then to propose that a new theory, complex responsive processes of relating (CRPR), might serve as a better foundation, one that more closely matches and justifies the principles of RCC.

Usual Ways of Looking at Communication and Relationship

At the heart of our usual way of looking at communication and relationships are 4 important underlying assumptions and perspectives. The first is the assumption that all behavior in a medical encounter is intentional. As I interact with you, I may be conscious of my intent, for example attempting to convince you to take your medicine. Or my purpose may be unconscious, for example, blaming you when your blood pressure is too high to avoid feelings of inadequacy and shame. Either way, we assume that if a behavior takes place, there must be some kind of motivating intention on somebody's part and that no behavior occurs without an intention.

Next is the assumption of linear causality: every effect has a cause that is ultimately discoverable (e.g., you take your medicine because you hold a belief that it will prevent you from having a stroke or because you trust me). Understanding causal factors allows us to predict outcomes (e.g., discovering patients' health beliefs or their perceptions of their relationships with doctors) or better yet to control them (e.g., changing patients' health beliefs or improving the quality of relationships). This assumption underlies virtually all biomedical research, including research on health care communication and relationships.

A third assumption is that communication is a process of information transfer. I have a thought within the private space of my own consciousness (“treating your high blood pressure will reduce your risk of stroke”). I encode that thought into words and gestures to elicit within the private space of your consciousness a similar meaning. Communication is thus a signaling process between individuals. The fidelity of transmission may be high or low. Indeed, much research has been carried out on personal, process, and environmental characteristics affecting the accuracy of communication.

The fourth element of our traditional perspective involves how we study relationship process. Most studies of communication and relationship use the encounter—the office visit—as the basic unit of observation. Typically, the analytic design consists of correlating independent variables (qualities or measures presumed to be relatively static over the course of the visit, e.g., the doctor's race or gender, the patient's perceived health status, or the doctor's collaborative communication style) with outcome variables (states or attitudes that are also presumed to be relatively enduring such as satisfaction with the visit, the patient's intention to take medication, or the patient's actual subsequent behavior). Other than sociolinguistic studies, there has been little attempt to study moment-to-moment dynamics during the encounter.

These 4 elements have served as the foundation for a productive and successful research effort that has contributed to improvements in medical practice and outcomes and to substantial changes in medical education. Nevertheless, important dimensions of relationship process are invisible to the traditional perspective, as we shall see shortly. We turn now to a very different theoretical foundation, one based in a new complexity-inspired theory called CRPR. I will describe CRPR, compare it with the traditional perspective, and show how it offers useful new views of familiar phenomena.

Self-organizing Patterns of Meaning and Relating

Complex responsive processes of relating integrates insights from sociology, social constructionism, and complexity to show how patterns of meaning and relating are continuously self-organizing in the course of human interactions.9,10 To understand the theory, we begin with the observation that human beings are a thoroughly social species; we grow up and live in a medium of continuous social interaction. Human infants and children depend on others and cannot survive by themselves. Even as adults, it is extraordinarily rare for humans to live without some degree of interaction. For most of us, daily life consists of abundant interactions with many people.

Ongoing social interactions are comprised of patterns of relating (such as role structures, dominance hierarchies, and behavioral norms) and patterns of meaning (such as vocabulary, concepts, and knowledge of both a general and particular nature; e.g., knowledge about all trees and about this tree, respectively). For patterns of meaning and relating to endure, they must be continuously re-enacted or recreated in each moment, rather like a piece of music that exists only so long as musicians play new notes in each new moment.

As patterns of meaning and relating are continuously re-enacted, they may exhibit stability (continuity) or they may vary, and sometimes altogether new patterns may arise spontaneously (novelty). The emergence of social patterns in each moment, both stable and novel, is a self-organizing process; the patterns form spontaneously without anyone's intention or direction. While we may seek to influence these patterns intentionally and we may even succeed for a time, they are ultimately unpredictable and beyond our control.

The notion of self-organizing patterns of meaning and relating may become clearer if we consider some concrete examples. First, imagine that you are talking with a colleague who uses a particular phrase or says something that relates coincidentally to something you were just reading, sparking a new idea for you. You share this thought with your colleague, who elaborates it further. As the idea “ping-pongs” between you, it grows to become a whole new pattern of meaning—an idea for a major project or a new theory. No one knew at the outset where the conversation would lead; no one held the intention of creating something new or directed the conversation toward its ultimate outcome. It just happened—hence, a self-organizing novel pattern of meaning. The development of a shared understanding of a patient's illness arises in a similar fashion during a medical encounter.

Now imagine that you are joining a preexisting group—say, your first day in a new practice. You look around to see how others are behaving to figure out “what the rules are around here” so that you can fit in (or more accurately, so you can avoid the dysphoria of being excluded, which depresses endorphin levels in your brain constituting an intrinsic narcotic withdrawal).11 Before long, you know how to act within the group's norms. Meanwhile, another new person joins the practice and watches you to learn what the rules are. Over the course of time, the practice's staff might turn over completely, yet the patterns of behavior may continue unchanged (e.g., a practice culture of competition and individualism, or of friendliness and mutual support). Again, no one directs this process. It just happens, a self-organizing stable pattern of relating.

I hope that these examples show that the self-organization of patterns in social process is commonplace. In fact, self-organization is ubiquitous; patterns of meaning and interacting are continuously forming, propagating, and evolving in every moment of every interaction. There are several basic principles of self-organizing process that open new avenues for studying and thinking about communication and relationship, and it is these principles to which we turn next.

Basic Principles of Self-organization

Self-organization occurs in the course of iterative reciprocal interactions. “Iterative” refers to an ongoing sequence of interactions; “reciprocal” refers to the mutual simultaneous influence that the interacting elements have on each other. If we represent linear causality as “A causes B,” then we can represent an iterative reciprocal interaction as “A influences B which influences A …” and so on. Iterative reciprocal interactions are the hallmark of nonlinear dynamics (complexity) in which there is no equilibrium state and patterns can shift unpredictably. Self-organization requires the simultaneous presence of order and disorder constraint and freedom. Without freedom all processes would be deterministic with no possibility of spontaneous variation or change; without constraints patterns could not form and take hold. Nonlinear dynamics and self-organizing patterns can be observed everywhere: in the reciprocal interactions of air molecules culminating in weather patterns, in the interplay of water molecules to form standing waves in a stream, in the co-evolution of species in an ecosystem, in the rise and fall of products and companies in the marketplace, and in the dissemination of ideas and fashions, to list but a few.

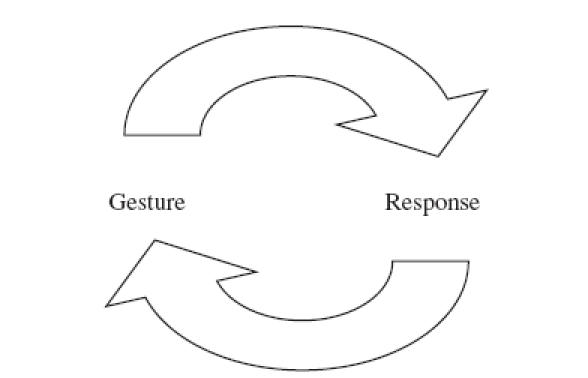

Interestingly, George Herbert Mead, the founder of social psychology, described just such a nonlinear dynamic in the emergence of meaning during social interactions (Fig. 1).12 He posited the hypothetical case of a dog gesturing to another dog by baring its teeth and snarling. At the moment of the snarl, the dog may be acting upon a particular motivation, but the ultimate meaning of its gesture cannot yet be known. Is it the initiation of a ritualized confrontation, an actual fight, or a round of play? The gesture's meaning is not a property of the gesture itself but rather arises in the interaction; it depends upon—and can only be completed by—the response it elicits from the other animal. And that response is itself a gesture, the significance of which is influenced by the response it in turn elicits from the first animal. As we shift from Mead's canine paradigm to the realm of human interaction, the potential meanings that can emerge increase innumerably, but the basic dynamic of patterns of meaning emerging spontaneously in the course of iterative reciprocal interactions is exactly the same.

FIGURE 1.

A simple schematic showing how a gesture and its response form and are formed by each other, thus displaying the hallmark characteristic of a nonlinear process. Each response is also the next gesture in the communication sequence, giving rise to its own response. The resulting iterative reciprocal interaction gives rise to self-organizing patterns of meaning and relating.

Another important property of nonlinear interactions is known as the amplification of small differences. In the course of an iterative reciprocal interaction, a slight difference—say, a new phrase or a slightly different behavior—may elicit a new response that carries the difference further and itself elicits a response that elaborates the difference further still. In just a few cycles of interaction, the small difference can be amplified into a new, transformative pattern. We saw this in the example above involving the germ of a new thought that grew quickly into a new project or theory. Another example is a casual slight that escalates rapidly into a sidewalk shooting. A third example is a patient's comment (e.g., “I feel cold all the time”) that culminates in a new pattern of meaning (a diagnosis of hypothyroidism).

One final implication of nonlinear dynamics is that the emergence of novel patterns of meaning or relating requires both diversity and responsiveness in the interaction. When little diversity is exhibited (perhaps because participants do not believe it is welcomed), there are fewer serendipitous differences to spark cascades of change. When responsiveness is poor—when individuals remain closed to or unaffected by one another—there is little opportunity for an emerging new pattern to become amplified; existing patterns will be difficult to dislodge.

To summarize, we have seen how patterns of meaning and relating can self-organize in the back-and-forth exchange of ongoing interaction. This is a nonlinear, unpredictable process in which patterns tend to replicate themselves but small differences can sometimes escalate rapidly into entirely new patterns. The development of new patterns depends upon the diversity and the responsiveness in the interaction.Table 1 compares CRPR with traditional perspectives on relational process.

Table 1.

A Comparison of Traditional and Complex Responsive Processes of Relating Perspectives on Relational Behavior

| Traditional | CRPR |

|---|---|

| Intentionality | Self-organization, spontaneous emergence |

| Linear causality; can be predicted and controlled | Nonlinear process, unpredictable |

| Information (pattern) transfer | Pattern construction in-the-moment |

| Correlations between static qualities | Observations of the emergence of novelty and continuity in patterns |

CRPR, Complex Responsive Processes of Relating

Before we move on, I should point out that CRPR is not the same as RCC; it is not a method, a relationship strategy, or a clinical approach for obtaining better results. It is a way of making sense of the relationship dynamics in which we find ourselves at all times. From the perspective of CRPR, RCC and traditional hierarchical patient-clinician relationships are just 2 different patterns of relating. CRPR helps us notice how either pattern is created and maintained moment by moment. It also yields interesting insights into some other familiar phenomena, as we will see in the next section.

A Fresh Look at Familiar Phenomena

As examples of the new insights that CRPR offers, let us consider several familiar phenomena—mind, communication, self and organizations. We have just seen how both novel and stable patterns can self-organize in the iterative interaction between 2 people. We can now understand the mind as being constituted of exactly the same self-organizing pattern-making, only in a private conversation rather than a public one: we gesture and respond to ourselves. A fleeting thought, memory, physical sensation, or any other stimulus can become amplified and elaborated in the iterative interaction of our sequential thoughts, allowing new ideas to emerge. An interesting new way to think about memory is as continuity in the patterns of meaning created in each moment in our private conversation. This conceptualization of memory is more dynamic than the popular “storage and retrieval” metaphor, and accounts for how memories can change over time.

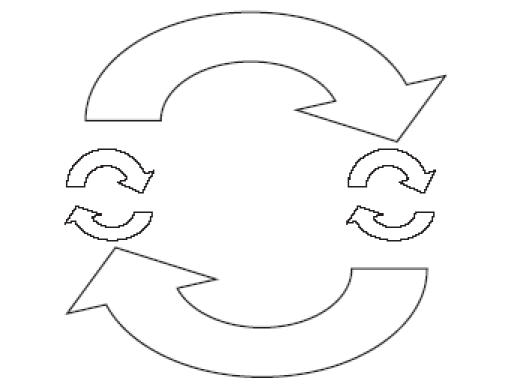

Our private conversations are unceasing. Gestures and responses in our public conversations originate in the themes of our private conversations, and at the same time, private conversations incorporate and are influenced by themes that arise in our public conversations (Fig. 2). Rather than seeing communication as the sending and receiving of discreet messages by 2 separate people/minds, we can regard it as the self-organizing construction and propagation of patterns of meaning within one seamless conversation comprised of both public and private elements. In this way, we can understand relationship as a process that transcends the separateness of the individual participants—it yields something that is different from just the sum of the parts.

FIGURE 2.

A schematic indicating the individual private conversations taking place simultaneously with the public conversation between the 2 individuals. The private conversations within the consciousness of individuals (small arrows) and the public conversations between individuals (large arrows) are characterized by the very same dynamics of iterative reciprocal interaction and self-organizing patterns. Emergent themes (patterns of meaning) flow back and forth through all the elements of the larger conversation.

Pushing ahead still further, we can conceive of “self” as a pattern of meaning pertaining to an individual's identity. My identity is not an attribute of, nor does it reside within, me. Rather, it is socially constructed and maintained in the course of my iterative interactions with you and everyone else I come in contact with; how you see me affects who I am. This is consistent with the common experience of feeling like a different person in the presence of different people. Our bodies may be discrete physical entities, but our “selves” form and persist only as themes in the medium of ongoing interaction.

Turning to the last familiar concept, organizations, we can now see that an organization, too, consists of themes formed and maintained in the ongoing social interaction of the people who have anything to do with it—owners, employees, customers, competitors, regulators, neighbors, and so on. The tangible manifestations of organizations—buildings, budgets, organizational charts—are created only when these organizational themes are sufficiently widespread and uniform. And as the conversational themes evolve, the tangible manifestations change—walls are torn down, new buildings are built, some people are laid off, others are hired. The organization's culture consists of patterns of relating that persist and change through ongoing interaction, for instance what one does or does not say at a meeting, who has access to what information, how decisions are made, and the whole panoply of power relations. The work of organizational change, therefore, consists not of designing new structures but of introducing new themes into the organizational conversation in the hope that they will amplify and disseminate.

Common to all 4 phenomena just discussed is ongoing pattern-making in the here-and-now of interactions between individuals. From a CRPR perspective, there is no beginning or end, no cause and effect, no determinants and outcomes. We are always in the middle of continuous pattern-making. And we are never anywhere other than right here in the living present.

Complex Responsive Processes of Relating and RCC: Implications for Practice

Complex responsive processes of relating offers a robust theoretical foundation for the practice of RCC. It calls attention to relational process—what are we doing together right here, right now? What patterns are we making and how? It catches us in the act of pattern-making, thus giving us an opportunity to be mindful about that process and, perhaps, to change it. Relationship-centered care and its predecessors Patient-Centered Care and the biopsychosocial model also call attention to relationship process, and advocate explicitly for a particular form of process involving a pattern of partnership. Complex responsive processes of relating also shows advocates of RCC that the most effective way to change a pattern (in this case, transforming hierarchical patterns into partnership) is to enact mindfully the new pattern in each moment, creating repeated disturbances in the traditional pattern in the hope that they will amplify and spread.

Complex responsive processes of relating provides a foundation for RCC's emphasis on self-awareness. It shows that our differences and diversity are the source of novelty (creativity) in our conversations and that our capacity for responsiveness—approaching differences with curiosity rather than fear and defensiveness and remaining open to being changed—enables new patterns to evolve.

Finally, and to me most important, CRPR relieves us of burdensome and unrealistic expectations of control and their constant shadow, the specter of failure and shame. Yet CRPR is not nihilistic—it shows how small actions can sometimes, unpredictably, amplify into transformational patterns. It shows how we influence each other by how we show up to each other. It draws our attention to the patterns of meaning and relating we are propagating or inhibiting by how we act in each moment, revealing the constant opportunity that we have to act differently and with greater mindfulness. In sum, the CRPR perspective gives theoretical support for the injunctions of RCC to hold our intentions lightly, let go of control, and attend to and trust the process.

Implications for Research

Earlier on, we saw that research guided by linear causality has an instrumental purpose: gaining the capacity to predict and control in order to improve outcomes. Research guided by CRPR is also motivated by the intention to improve care but the strategy is quite different. Its goal is to enable us to participate more mindfully in ongoing relational process. Complex responsive processes of relating helps us observe relational process with such questions in mind as:

What are the current patterns of relating? What are the patterns of meaning, including themes of individual and organizational identity? How are these patterns brought forward or re-enacted in each moment?

What new patterns are emerging? How did they get started? What is supporting or inhibiting their spread?

What are the constraints and what degrees of freedom co-exist in this situation and how do they affect the patterns that are emerging?

What am I experiencing as the researcher? How is my presence and participation influencing the patterns under observation? What effect is this research having on me?

Complex responsive processes of relating may inspire the creation and use of new research methods and analytic tools. One that comes to mind is a system of tablature akin to musical notation for documenting multiple dimensions of interaction simultaneously—for instance, words, inflection, proxemics, physiologic states, and so forth.13,14 This would allow for the study of resonance and dissonance across levels, much as a musicologist studies the relationship between the different parts in a musical score. Another potential new tool is a mathematical language for describing “possibility spaces”—given a specific set of constraints, what is the range of patterns that can emerge and what patterns are precluded? As one who was thoroughly trained in the linear tradition, I have trouble envisioning further possibilities, but I can propose these starting points, and I am confident that others can take this much farther than I can.

Concluding Thoughts

Traditional conceptualizations of health care communication and relationship have been based on assumptions about the origin of relationship behavior in intentions, linear causality, communication as information transfer, and the study of stable determinants of communication and relationship behavior. Under the guidance of this traditional framework, many important observations have been made and useful principles have been derived. However, this perspective does not draw attention to what is arguably at the very heart of relational process—the continuous and spontaneous pattern-making of moment-to-moment interaction. Moreover, the traditional view does not account for the most basic tenets of RCC—the capacity of individuals working in partnership to produce results that are greater than the sum of their individual efforts, the value of collaborative process, and the importance of self-awareness and personal authenticity.

The theory of CRPR focuses directly on these matters. It calls attention to the dynamic in-the-moment nature of relational process and the self-organizing patterns of meaning and relating that emerge in the course of ongoing conversation between people and in our thoughts. It casts an entirely different light on intention and purpose. The traditional perspective sees them as outside of and primary causes of interactive behavior, whereas CRPR shows them to be patterns of meaning that themselves arise in the course of iterative interaction and then influence the course of subsequent interactions.

Complex responsive processes of relating highlights the importance of responsiveness and diversity for creativity and adaptibility (the emergence of novel patterns). “Responsiveness” is another way of describing the state of relatedness that is at the heart of RCC and is fostered by the development of outstanding relationship skills. “Diversity” refers to the expression of individual differences, corresponding closely to the emphasis in RCC on authenticity and self-awareness.

We need not choose between the traditional and CRPR perspectives. Most of the insights of traditional linear causal theories can be integrated into a CRPR perspective when recast in terms of constraints on self-organizing process. For example, rather than seeing a patient's health beliefs as the cause of his behavior, we can explore how a particular belief constrains the range of possible behaviors that might emerge and how a different belief opens up a new range of potential self-organizing patterns. We can also see that changing that belief involves changes in ongoing patterns of meaning and identity rather than just the effective transfer of information.

Complex responsive processes of relating opens up for us a whole new realm of observations and questions. It invites us to be less preoccupied with how to obtain desired results and instead pay more attention to what we are doing together, right here right now. It recognizes that whether we view ourselves at the level of individual selves, families, organizations, or societies, we are not static but rather in a perpetual state of becoming, constituted of patterns that self-organize amidst freedom and constraint here in the living present. For all these reasons, I believe that in the theory of complex responsive processes, RCC finally has a sound theoretical base.

Acknowledgments

For help in learning and applying the theory of CRPR, I am deeply indebted to Ralph Stacey, Thomas Smith, many faculty members and colleagues at the University of Hertfordshire's Complexity and Management Centre, and many colleagues who have worked with me to apply principles of RCC in administrative contexts. Rich Frankel and Penny Williamson provided helpful critiques of the manuscript. I am grateful to Tom Inui and Rich Frankel for the invitation to bring this theory before an audience of health services and communications researchers.

FERENCES

- 1.Tresolini CP and the Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence C, Weisz G. Greater Than the Parts: Holism in Biomedicine 1920–50. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWhinney IR. Beyond diagnosis: an approach to the integration of behavioral science and clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:384–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197208242870805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankel RM, Quill TE, McDaniel SH. The Biopsychosocial Approach: Past, Present and Future. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:576–82. doi: 10.1370/afm.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for Communicating with Patients. 2nd. Abingden, Oxon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey R. Complex Responsive Process in Organizations: Learning and knowledge Creation. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stacey R. Complexity in Group Processes: A Radically Social Understanding of Individuals. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TS, Stevens GT, Caldwell S. The familiar and the strange: Hopfield network models for prototype-entrained attachment-mediated neurophysiology. Soc Perspectives Emotion. 1999;5:213–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead GH. Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pittinger RE, Hockett CF, Danehy JJ. The First Five Minutes. Ithaca, NY: Paul Martineau; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheflen A. Communicational Structure: Analysis of a Psychotherapy Transaction. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]