Abstract

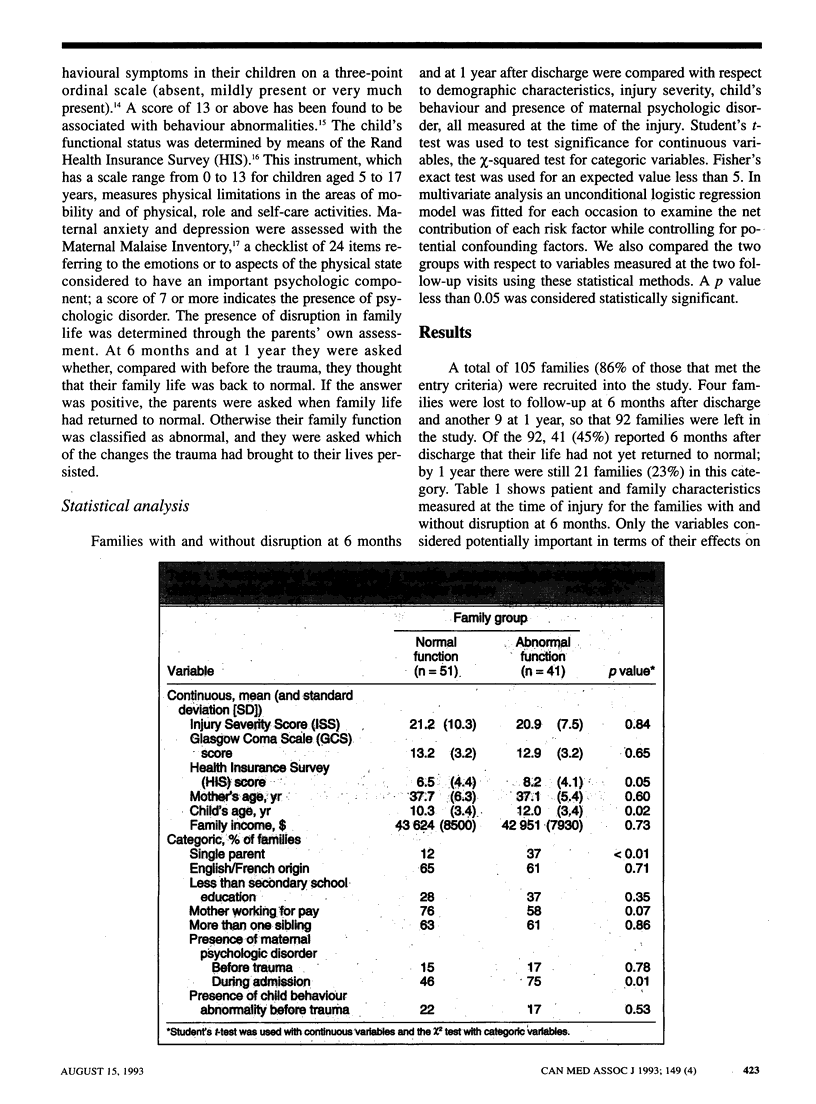

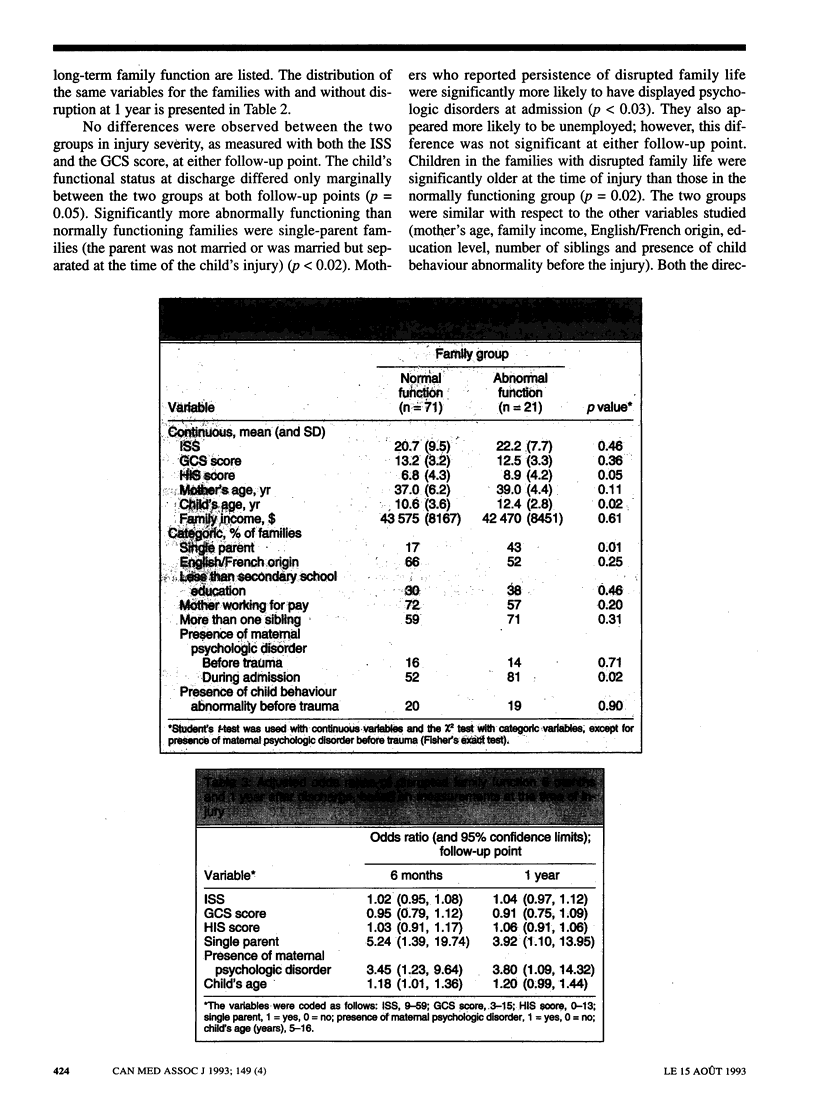

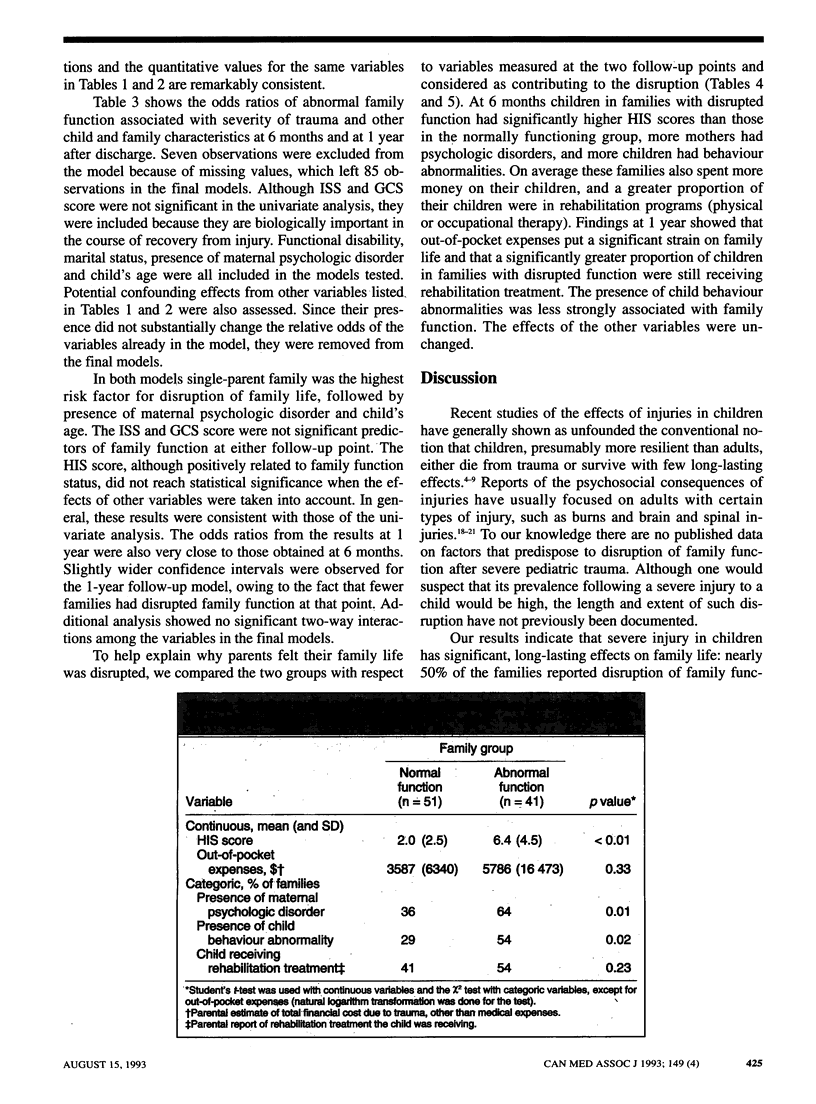

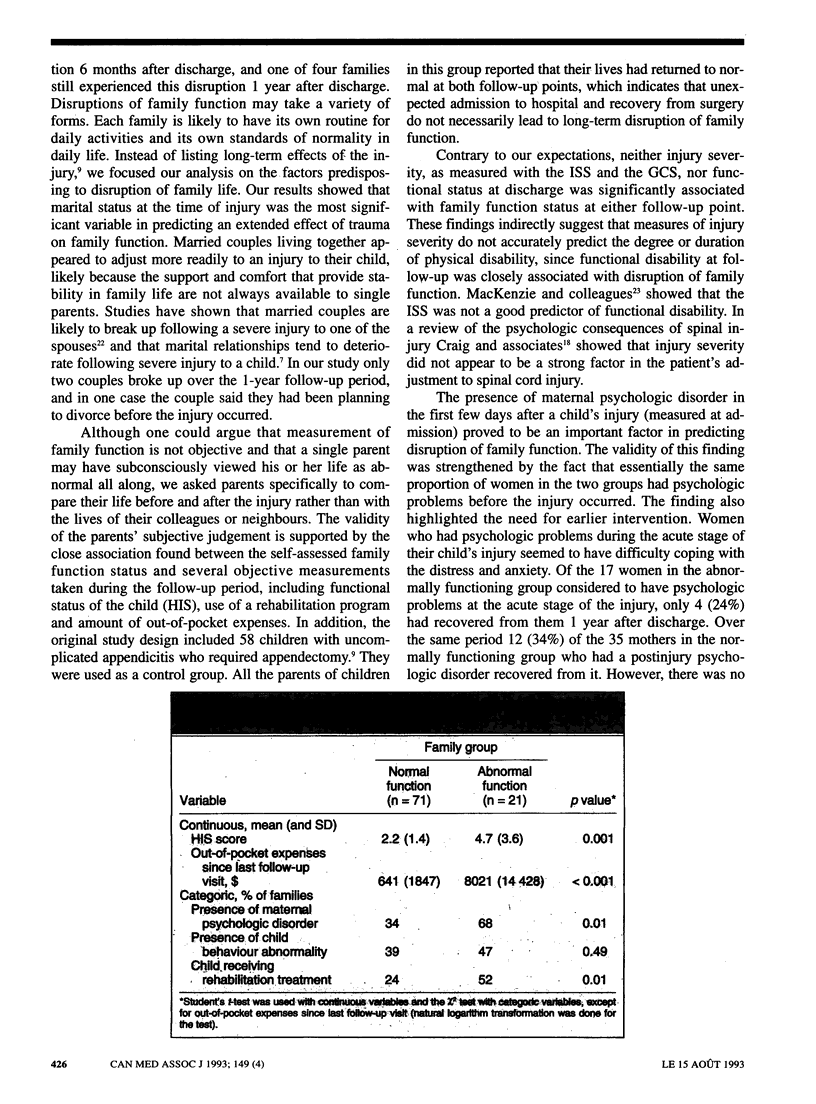

OBJECTIVE: To identify risk factors for long-lasting disruption of family function following pediatric trauma that can be measured at the time of trauma. DESIGN: Prospective, exploratory study. Personal interviews were conducted at the time of admission and 6 months and 1 year after discharge. SETTING: Level I regional pediatric trauma centre. PARTICIPANTS: One hundred and five families (86% of those eligible) with a child admitted to hospital for severe trauma with an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 4 or higher or with two or more injuries in different body parts and AIS scores of 2 or higher were recruited; 13 families were lost to follow-up at 6 months or 1 year, so their data were not included in the analyses. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Family function status (normal or abnormal compared with function before the injury), demographic characteristics of the parents and child, injury severity, presence of maternal psychologic disorder, presence of child behaviour abnormality and functional status of the child. MAIN RESULTS: At 6 months and at 1 year 41 families (45%) and 21 families (23%) respectively reported that their family lives had not returned to normal. The relative odds for disruption of family life were about five times higher (95% confidence limits [CL] 1.4 and 19.7) and four times higher (95% CL 1.1 and 14.0) for single-parent families than for families with married parents living together at 6 months and 1 year respectively. The presence of maternal psychologic disorders at admission and increased age of the injured child were also significantly associated with extended disruption of family function. Injury severity and functional status at discharge were not good predictors of family function. CONCLUSIONS: Severe injury to a child places a heavy strain on normal family function. In particular, single parents and parents experiencing mental or emotional problems at the acute stage of the injury need help in coping with their reactions to the trauma and may benefit from individual or group counseling.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker S. P., O'Neill B., Haddon W., Jr, Long W. B. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974 Mar;14(3):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A. R., Hancock K. M., Dickson H., Martin J., Chang E. Psychological consequences of spinal injury: a review of the literature. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990 Sep;24(3):418–425. doi: 10.3109/00048679009077711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVivo M. J., Fine P. R. Spinal cord injury: its short-term impact on marital status. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985 Aug;66(8):501–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife D., Barancik J. I., Chatterjee B. F. Northeastern Ohio Trauma Study: II. Injury rates by age, sex, and cause. Am J Public Health. 1984 May;74(5):473–478. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.5.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans B. M., di Scala C. Rehabilitation of severely injured children. West J Med. 1991 May;154(5):566–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. H., Schwaitzberg S. D., Seman T. M., Herrmann C. The hidden morbidity of pediatric trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 1989 Jan;24(1):103–106. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsman I. S., Baum C. G., Arnkoff D. B., Craig M. J., Lynch I., Copes W. S., Champion H. R. The psychosocial consequences of traumatic injury. J Behav Med. 1990 Dec;13(6):561–581. doi: 10.1007/BF00844735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie E. J., Shapiro S., Moody M., Siegel J. H., Smith R. T. Predicting posttrauma functional disability for individuals without severe brain injury. Med Care. 1986 May;24(5):377–387. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin E. The psychological trauma and management of severe burns in children and adolescents. Br J Hosp Med. 1988 Sep;40(3):210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderström S., Fogelsjö A., Fugl-Meyer K. S., Stensson S. A program for crisis-intervention after traumatic brain injury. Scand J Rehabil Med Suppl. 1988;17:47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate R. L., Lulham J. M., Broe G. A., Strettles B., Pfaff A. Psychosocial outcome for the survivors of severe blunt head injury: the results from a consecutive series of 100 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989 Oct;52(10):1128–1134. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.10.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G., Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troop P. A. Accidents to children: an analysis of inpatient admissions. Public Health. 1986 Sep;100(5):278–285. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(86)80048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson D. E., Scorpio R. J., Spence L. J., Kenney B. D., Chipman M. L., Netley C. T., Hu X. The physical, psychological, and socioeconomic costs of pediatric trauma. J Trauma. 1992 Aug;33(2):252–257. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson D. E., Williams J. I., Spence L. J., Filler R. M., Armstrong P. F., Pearl R. H. Functional outcome in pediatric trauma. J Trauma. 1989 May;29(5):589–592. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]