Abstract

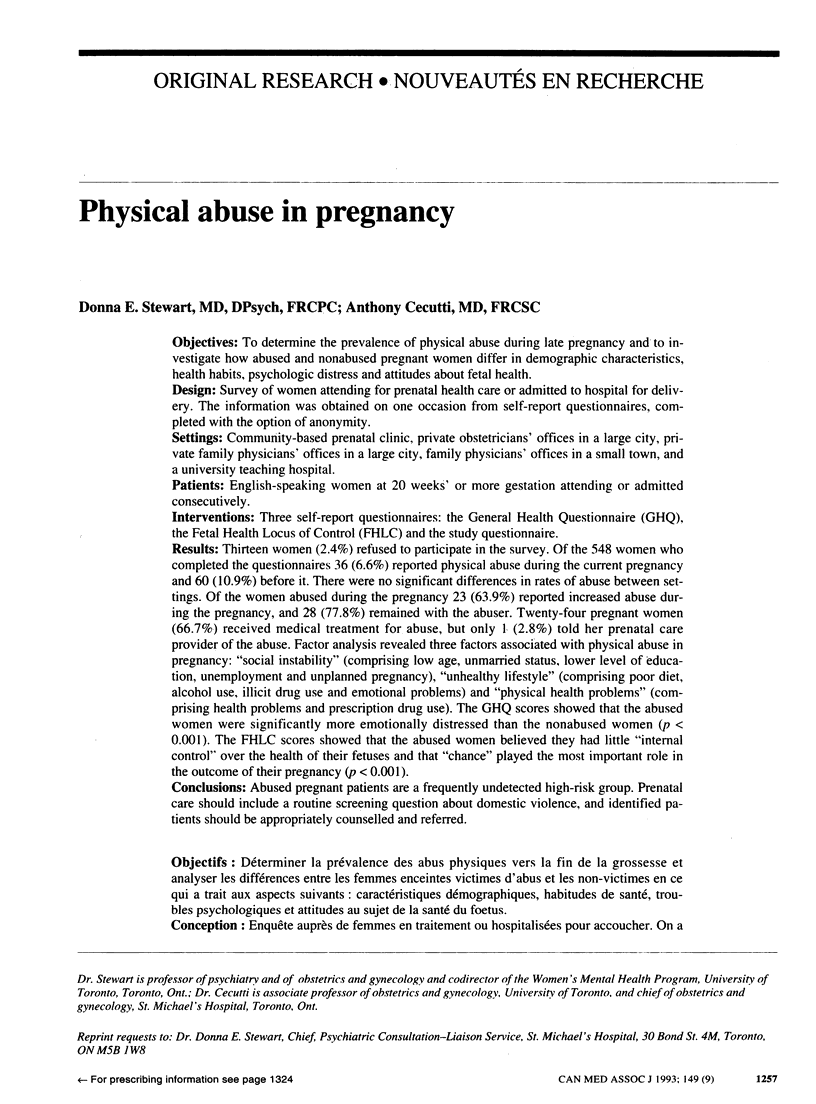

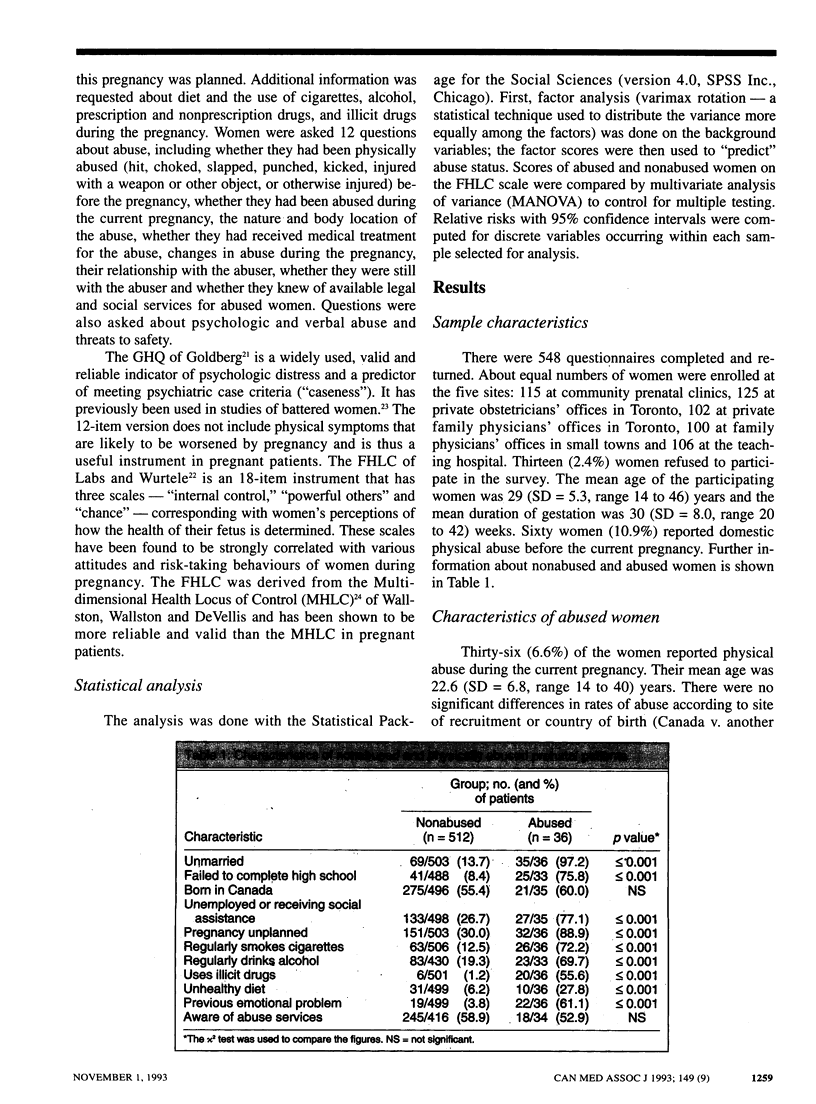

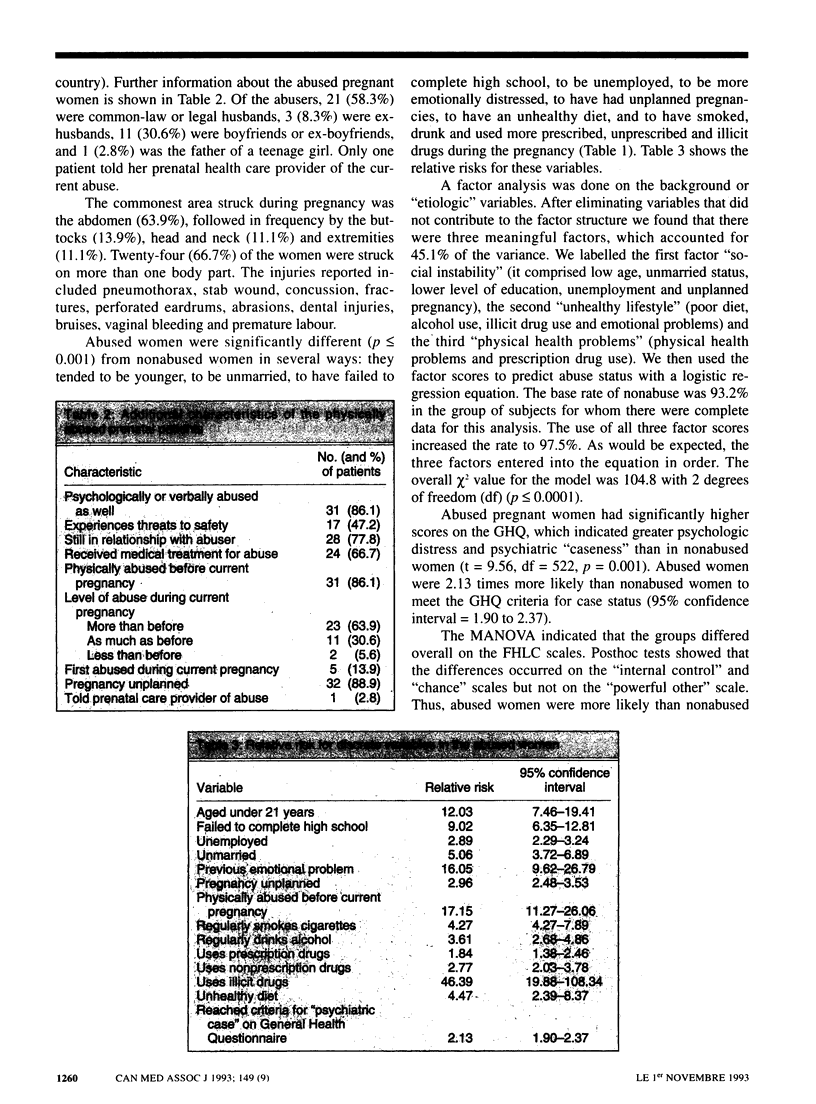

OBJECTIVES: To determine the prevalence of physical abuse during late pregnancy and to investigate how abused and nonabused pregnant women differ in demographic characteristics, health habits, psychologic distress and attitudes about fetal health. DESIGN: Survey of women attending for prenatal health care or admitted to hospital for delivery. The information was obtained on one occasion from self-report questionnaires, completed with the option of anonymity. SETTINGS: Community-based prenatal clinic, private obstetricians' offices in a large city, private family physicians' offices in a large city, family physicians' offices in a small town, and a university teaching hospital. PATIENTS: English-speaking women at 20 weeks' or more gestation attending or admitted consecutively. INTERVENTIONS: Three self-report questionnaires: the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), the Fetal Health Locus of Control (FHLC) and the study questionnaire. RESULTS: Thirteen women (2.4%) refused to participate in the survey. Of the 548 women who completed the questionnaires 36 (6.6%) reported physical abuse during the current pregnancy and 60 (10.9%) before it. There were no significant differences in rates of abuse between settings. Of the women abused during the pregnancy 23 (63.9%) reported increased abuse during the pregnancy, and 28 (77.8%) remained with the abuser. Twenty-four pregnant women (66.7%) received medical treatment for abuse, but only 1 (2.8%) told her prenatal care provider of the abuse. Factor analysis revealed three factors associated with physical abuse in pregnancy: "social instability" (comprising low age, unmarried status, lower level of education, unemployment and unplanned pregnancy), "unhealthy lifestyle" (comprising poor diet, alcohol use, illicit drug use and emotional problems) and "physical health problems" (comprising health problems and prescription drug use). The GHQ scores showed that the abused women were significantly more emotionally distressed than the nonabused women (p < 0.001). The FHLC scores showed that the abused women believed they had little "internal control" over the health of their fetuses and that "chance" played the most important role in the outcome of their pregnancy (p < 0.001). CONCLUSIONS: Abused pregnant patients are a frequently undetected high-risk group. Prenatal care should include a routine screening question about domestic violence, and identified patients should be appropriately counselled and referred.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amaro H., Fried L. E., Cabral H., Zuckerman B. Violence during pregnancy and substance use. Am J Public Health. 1990 May;80(5):575–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J. E. Wife assault: physicians cannot ignore it. CMAJ. 1991 Feb 1;144(3):283–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson A. B., Stiglich N. J., Wilkinson G. S., Anderson G. D. Drug abuse and other risk factors for physical abuse in pregnancy among white non-Hispanic, black, and Hispanic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jun;164(6 Pt 1):1491–1499. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland R., Orn H. Family violence and psychiatric disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1986 Mar;31(2):129–137. doi: 10.1177/070674378603100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn D. K. Domestic violence and pregnancy. Implications for practice. J Nurse Midwifery. 1990 Mar-Apr;35(2):86–98. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(90)90064-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock L. F., McFarlane J. The birth-weight/battering connection. Am J Nurs. 1989 Sep;89(9):1153–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein L. J. Spouse abuse and other domestic violence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1988 Dec;11(4):611–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flitcraft A. H. Violence, values, and gender. JAMA. 1992 Jun 17;267(23):3194–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton A. S., McFarlane J., Anderson E. T. Battered and pregnant: a prevalence study. Am J Public Health. 1987 Oct;77(10):1337–1339. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.10.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton A. S., Snodgrass F. G. Battering during pregnancy: intervention strategies. Birth. 1987 Sep;14(3):142–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1987.tb01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilberman E. Overview: the "wife-beater's wife" reconsidered. Am J Psychiatry. 1980 Nov;137(11):1336–1347. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.11.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard P. J. Physical abuse in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Aug;66(2):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling G. T., Sugarman D. B. An analysis of risk markers in husband to wife violence: the current state of knowledge. Violence Vict. 1986 Summer;1(2):101–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe P., Wolfe D. A., Wilson S., Zak L. Emotional and physical health problems of battered women. Can J Psychiatry. 1986 Oct;31(7):625–629. doi: 10.1177/070674378603100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labs S. M., Wurtele S. K. Fetal health locus of control scale: development and validation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986 Dec;54(6):814–819. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.6.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J. Battering during pregnancy: tip of an iceberg revealed. Women Health. 1989;15(3):69–84. doi: 10.1300/J013v15n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J., Parker B., Soeken K., Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992 Jun 17;267(23):3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberger E. H., Barkan S. E., Lieberman E. S., McCormick M. C., Yllo K., Gary L. T., Schechter S. Abuse of pregnant women and adverse birth outcome. Current knowledge and implications for practice. JAMA. 1992 May 6;267(17):2370–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall S. E., Greaves L. J., Lent B. Wife battering: an emerging problem in public health. Can J Public Health. 1985 Sep-Oct;76(5):297–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae-Grant Q. Presidential address. Family violence--myths, measures and mandates. Can J Psychiatry. 1983 Nov;28(7):505–512. doi: 10.1177/070674378302800701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall T. ACOG renews domestic violence campaign, calls for changes in medical school curricula. JAMA. 1992 Jun 17;267(23):3131–3131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R. W. Battered wife syndrome. Can Med Assoc J. 1984 Mar 15;130(6):709–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallston K. A., Wallston B. S., DeVellis R. Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) Scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978 Spring;6(2):160–170. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]