Abstract

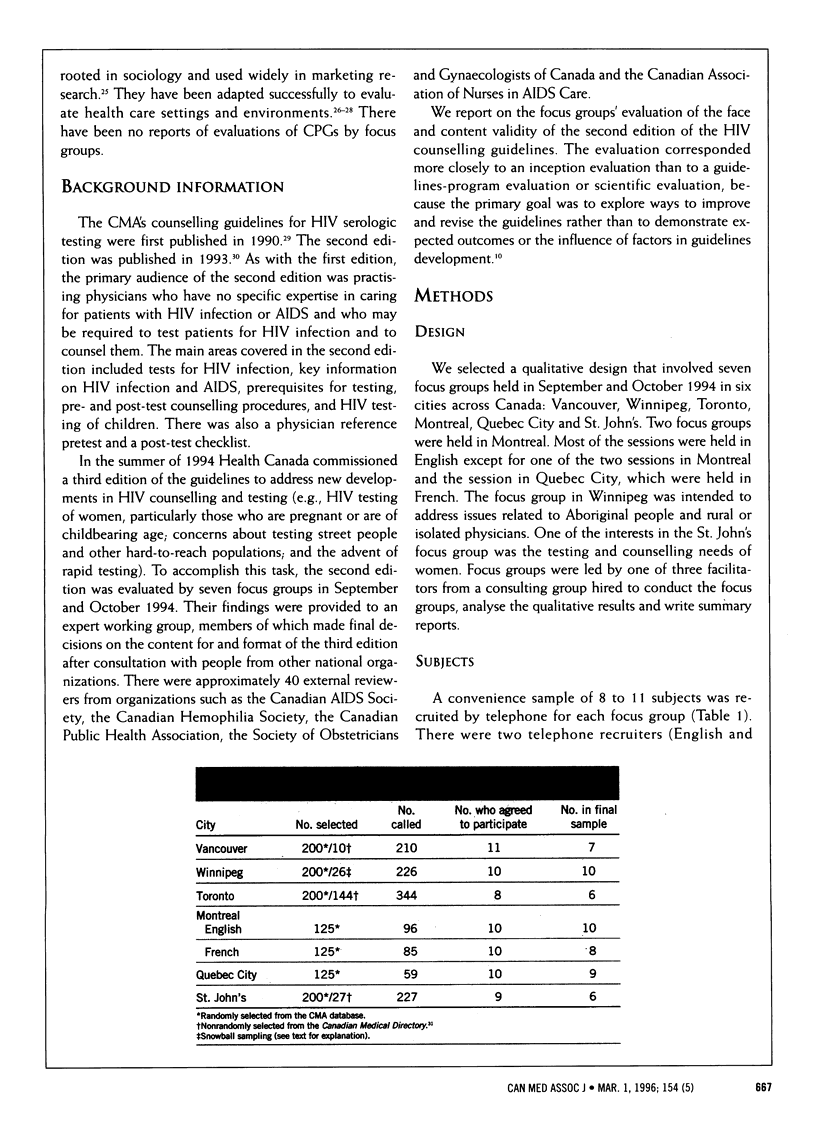

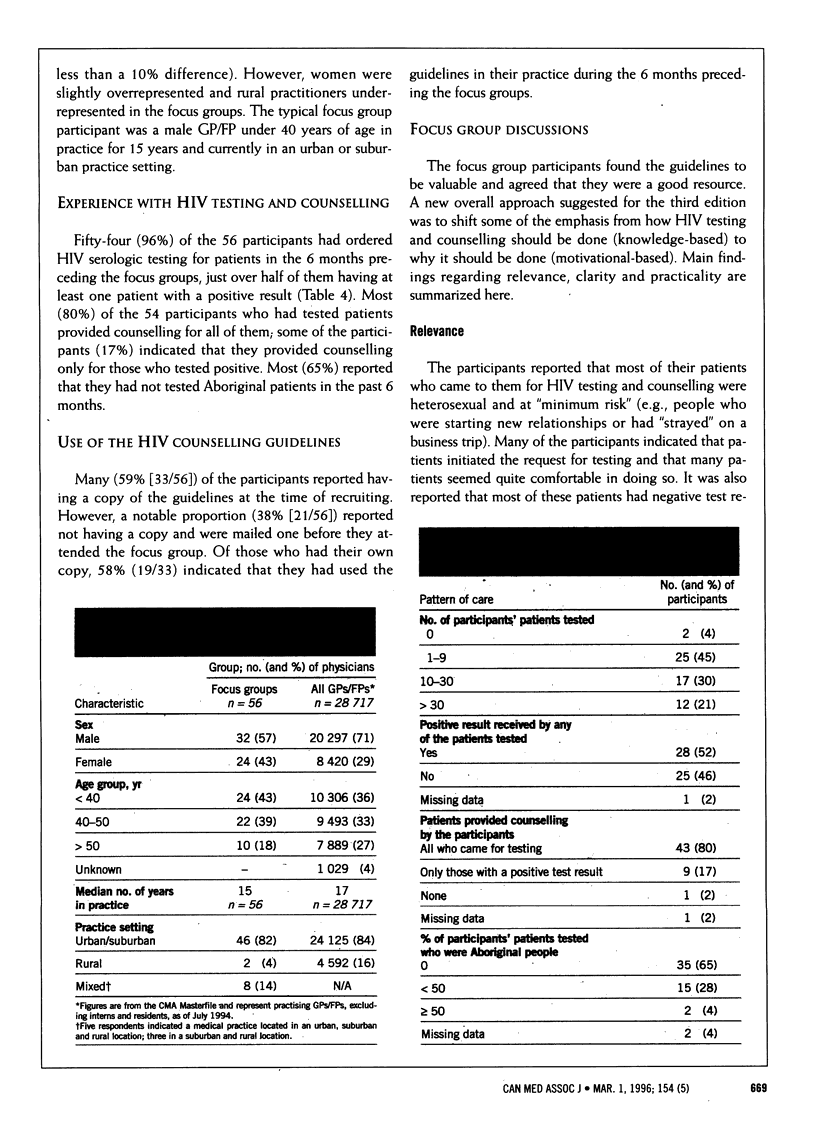

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the face and content validity of the CMA's counselling guidelines for HIV serologic testing in order to prepare a revised edition. DESIGN: Qualitative evaluation by structured focus groups in September and October 1994 to assess the relevance, clarity and practicality of the guidelines, followed by content analysis of the discussions. SETTING: Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, Quebec City and St. John's. PARTICIPANTS: Primary care physicians randomly selected from the CMA database and nonrandomly selected from the Canadian Medical Directory who had limited experience with HIV testing and counselling and who provided an appropriate mix of characteristics in terms of practice type (solo and group), setting (urban and rural), age and sex. A total of 1247 physicians were approached for the study; a convenience sample of 68 were recruited, of whom 56 participated. The average size of each focus group was eight physicians. OUTCOME MEASURES: Clinical experience and information sources with respect to HIV testing, reactions to the counselling guidelines, and suggestions for revisions and improvements to the guidelines. RESULTS: Most (96% [54/56] of the participants had ordered HIV serologic testing for patients in the 6 months preceding the focus groups, and about half of them (52% [28/54]) had at least one patient with a positive test result. Many (59% [33/56]) of the participants had a copy of the guidelines at the time of recruitment; 19 (58%) of them had used the guidelines in the months before the focus groups. The parts of the guidelines most often read were the checklists and inset boxes. Recommendations for revisions in content were for more information on legal and ethical issues, information on new issues (e.g., rapid testing) and guidelines on how best to tell a patient about a positive test result; recommendations for revisions in format included more tables, algorithms, bulleted points and white space, less text, larger type and plainer language. CONCLUSIONS: The focus groups provided detailed, credible and consistent information about the face and content validity of the HIV counselling guidelines. They are a useful qualitative method for evaluating the relevance, clarity and practicality of clinical practice guidelines at the inception or revision stage.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Audet A. M., Greenfield S., Field M. Medical practice guidelines: current activities and future directions. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Nov 1;113(9):709–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-9-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basinski A. S. Evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1995 Dec 1;153(11):1575–1581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista R. N., Hodge M. J. Clinical practice guidelines: between science and art. CMAJ. 1993 Feb 1;148(3):385–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A. O., Battista R. N., Hodge M. J., Lewis S., Basinski A., Davis D. Report on activities and attitudes of organizations active in the clinical practice guidelines field. CMAJ. 1995 Oct 1;153(7):901–907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J. M., Russell I. T. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993 Nov 27;342(8883):1317–1322. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. T., Toepp M. C. Practice parameters: development, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992 Dec;18(12):405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J., Anderson G. M., Domnick-Pierre K., Vayda E., Enkin M. W., Hannah W. J. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 9;321(19):1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittman B. S., Tonesk X., Jacobson P. D. Implementing clinical practice guidelines: social influence strategies and practitioner behavior change. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992 Dec;18(12):413–422. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm L., Windahl S. Focus groups--some suggestions. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1988;1:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995 Jul 1;311(6996):42–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatromoni P. A., Milbauer M., Posner B. M., Carballeira N. P., Brunt M., Chipkin S. R. Use of focus groups to explore nutrition practices and health beliefs of urban Caribbean Latinos with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1994 Aug;17(8):869–873. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A. G., Shepperd J. The use of focus groups in health research. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl. 1988;1:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf S. H. Practice guidelines, a new reality in medicine. II. Methods of developing guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 1992 May;152(5):946–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]