Abstract

In this article, we present key lessons that we have learned from (1) a long program of research on an empirically supported treatment, brief strategic family therapy (BSFT), and (2) our ongoing research and training efforts related to transporting BSFT to the front lines of practice. After briefly presenting the rationale for working with the family when addressing behavior problems and substance abuse in adolescent populations, particularly among Hispanic adolescents, we summarize key findings from our 30-year program of research. The article closes by identifying barriers to the widespread adoption of empirically supported treatments and by presenting current work within the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Clinical Trials Network that attempts to address these barriers and obstacles.

Keywords: Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment, Research-to-Practice, Family Therapy, Dissemination

The mental health and substance abuse treatment fields have increasingly emphasized the importance of using empirically supported treatments on a wider scale (Barlow, 1996; Lamb, Greenlick, & McCarty, 1998). In the treatment of child and adolescent behavior problems and substance abuse, brief strategic family therapy (BSFT) is one of several family-based approaches that are prominent among the list of empirically supported treatments (Sexton, Robbins, Holliman, Mease, & Mayorga, 2003). BSFT has been tested largely with Hispanic samples but is now being tested in a multisite effectiveness trial with diverse populations.

The reasons for accelerating the widespread use of empirically supported treatments are many. The selection of empirically supported treatments helps to minimize the use of treatments that have little impact or that can potentially cause harm (e.g., Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). In addition to improving patient care and outcomes, empirically supported treatments can also facilitate the training of therapists and the implementation of the therapy, and can bolster accountability of treatment providers and influence policy makers to fund treatments based on effectiveness data (Elliott, 1998). This pressure, together with the body of evidence supporting family therapy, has prompted a growing movement toward the adoption of family therapy in community treatment agencies (both nationally and internationally), with literally hundreds of agencies currently receiving training and participating in the implementation of research-supported family approaches. Although the demand for training in research-supported interventions has been a positive development, there is still much to be known about the many challenges to selecting and training therapists, to sustaining the treatment in an agency over time, and to ensuring the continued fidelity needed to produce good outcomes.

As is the case with other teams of investigators who have developed empirically supported treatments, our research team is guided by two major goals: (1) learning more about how our treatment works, when, and for whom, with the goal of enhancing its efficacy, and (2) refining our understanding and practice of “successful dissemination” of current empirically supported treatments to the front lines of treatment. The purpose of this article is (1) to describe some of the major lessons learned from our program of research and benefits that we have documented from the use of specialized and manualized interventions to tackle such problems as engagement of reluctant family members and treatment of adolescent substance abuse and behavior problems, and (2) to describe some of the challenges we see to widespread adoption of the treatment.

BRIEF STRATEGIC FAMILY THERAPY AS THE CORE OF OUR PROGRAM OF RESEARCH

Although there are many similarities across family approaches that have been shown to be efficacious with substance-abusing adolescents in multiple research studies (Sexton et al., 2003), the models are quite different in their underlying treatment philosophies and implementation strategies. The family therapy model that has been the main focus of our program of research to date, brief strategic family therapy (BSFT; Szapocznik, Hervis, & Schwartz, 2003; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1989), has shown evidence of efficacy in the engagement and treatment of substance-abusing youth and was the first empirically supported treatment for Hispanic substance-abusing youth (Szapocznik, Amaro, et al., 2003). Unique features differentiate BSFT from other family treatment approaches. The integration of structural (Minuchin & Fishman, 1981) and strategic (Haley, 1976) theory and principles is perhaps the most discriminating feature of BSFT. Although many family therapy models incorporate structural and strategic therapy interventions, such as multisystemic therapy (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998) and multidimensional family therapy (Liddle, 2002), BSFT is the only empirically validated family therapy for adolescents that relies almost exclusively on a coherent integration of structural and strategic theory and therapy. For example, assessment and diagnosis in BSFT is based on structural theories of family functioning and complex patterns are identified in five structural domains: structure, conflict resolution, resonance, developmental stage, and identified patienthood. In contrast, assessment and intervention in multisystemic therapy involves the systematic identification of social ecological processes, which include the family but also go well beyond the family. Assessment and intervention in multidimensional family therapy includes the systematic integration of individual (e.g., attachment), family (e.g., structural), and social ecological domains. Although some members of our team are developing new interventions that integrate an individual focus (Santisteban, Mena, & Suarez-Morales, 2006) and an ecological focus (Robbins, Schwartz, & Szapocznik, 2003), BSFT has maintained a consistent focus on the centrality of “within-family” work.

The specific structural and strategic aspects of the model are also unique because BSFT consists of theoretically and clinically distinct strategies. There are research-based strategies for engaging reluctant family members into treatment (see engagement work described in detail below), for joining with family members (Sexton & Robbins, 2005), for diagnosing and assessing family interactions (Szapocznik et al., 1991), and for restructuring family interactions that have been linked to severe adolescent behavior problems and substance abuse (Santisteban et al., 2003). Such dimensions of family functioning include family conflict, lack of support, poor communication, poor limit-setting, inadequate parental monitoring, inconsistent parenting, and parental drug use, which have been shown to impact the emergence and maintenance of adolescent behavior problems and drug use (Ary, Duncan, Duncan & Hops, 1999; Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & Henry, 2000; Lindahl & Malik, 1999; Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1998). Finally, BSFT interventions have applied findings from basic research on the cultural factors prominent among the Hispanic population (Szapocznik, Scopetta, Aranalde, & Kurtines, 1978).

BSFT can address powerful stressors faced by Hispanic families that can adversely impact family functioning (Santisteban, Muir-Malcolm, Mitrani & Szapocznik, 2002) and is consistent with a strong family orientation found in research with Hispanics (Marin, 1993; Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Stressors such as migration stress, disruption of support systems, discrimination and social inequalities, separation of family members who move across national borders, and acculturation stress can adversely impact family communication, family cohesion, and parenting practices in Hispanic families. It should be pointed out that although acculturation conflicts are most powerful following immigration, these conflicts do not require crossing national borders. Youngsters can acculturate away from the core beliefs, values, and behaviors of ethnic communities and enclaves within the United States mainland. Equally important, Falicov (2003) described the need to use a “sociopolitical lens” to fully appreciate the social injustices and the limited social and economic opportunities that are prominent in the lives of Hispanics and other minority groups. These limited opportunities are painfully evident in access (or lack thereof) to work, educational, substance abuse, and mental health resources. Counselors working with families have a unique opportunity to address the impact of these powerful contextual stressors on individuals and families. BSFT attempts to help families adaptively address these stressors, to empower families in their interactions with the larger social systems, and to work on important underlying family vulnerabilities to these stressors.

SOME LESSONS LEARNED FROM OUR PROGRAM OF RESEARCH ON BRIEF STRATEGIC FAMILY THERAPY

Brief strategic family therapy and many of its central components have been tested in a variety of studies and have led to several important findings. In the engagement domain, BSFT has been shown to be efficacious in engaging reluctant family members into treatment. In the outcome domain, BSFT has been shown to reduce serious behavior problems and drug use among adolescents. The major studies are described below.

Findings on Engagement

The engagement of family members into treatment has been a major challenge to family therapy, particularly in drug abuse treatment (Santisteban & Szapocznik, 1994; Stanton & Heath, 2004). Rarely are all family members enthusiastic about attending treatment when only one family member appears to be showing symptoms. To address this clinical challenge, specialized engagement strategies were developed and tested in randomized trials.

The two most rigorous studies of engagement assigned families to either “specialized engagement interventions” or to a control condition: “engagement as usual.” The control condition was designed to replicate the scheduling and intake procedures typically used in outpatient centers and was based on a survey conducted with Hispanic-serving community agencies. This generally consisted of polite and empathic conversation while scheduling appointments. Specialized engagement strategies were developed based on a clinical analysis that showed that some common patterns led to problems in engaging all key family members of substance-abusing youth. Specialized strategies were designed for reaching reluctant family members (for example, powerful adolescents drug users or family members trying to maintain the status quo) and for addressing issues that keep family members out of treatment (for example, marital conflicts or parental substance abuse that kept one member out). Specialized interventions would usually involve well-planned telephone interventions with reluctant family members. These interventions sought to identify and address the reasons for their reluctance but sometimes also included going out to meet family members in person. Results of both major studies showed that specialized interventions were very effective in increasing the percentage of families engaged into treatment and in retaining them in treatment. In one study, 108 families of Hispanic behavior-problem youth were randomly assigned (Szapocznik et al., 1988) to one of the two conditions described above. In this study, 93% of the families in the specialized engagement condition, compared with only 42% of the families in the engagement-as-usual condition, were engaged into treatment, a significant difference, X2 (1,108) = 29.93,p<.0001. It should be noted that families were considered engaged if they attended the intake session. In the second study, 193 Hispanic families of behavior-problem adolescents were assigned to the same two conditions (Santisteban et al., 1996). In this study, the engagement rates were somewhat lower because more stringent criteria for engagement (intake session plus one therapy session) were used to define engagement. In this study, 81% of the families were successfully engaged, whereas in the control conditions, 60% of the families were successfully engaged, a significant difference, X2 (1,193) = 7.53, p < .006.

This pair of studies on engagement succeeded in showing that specialized engagement strategies could be effective in bringing to treatment family members who are not showing symptoms and who are reluctant to come into treatment. The philosophical shift that we think was most needed was that clinicians were trained to begin their diagnostic work and interventions focused on engagement over the phone, prior to having the family in the room. The diagnostic work involved exploring and identifying the systemic obstacles to having the entire family come to intake and a session. The engagement work focused on tailoring the intervention to the specific family needs. Because our research showed that the vast majority of effective interventions were conducted by phone rather than requiring out-of-office visits (Santisteban et al., 1996), this intervention is one that can be implemented in a cost-effective fashion.

Outcome Results of BSFT with Behavior-Problem and Drug-Abusing Youth

Several studies have tested the efficacy of BSFT with different child and adolescent subgroups. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to present the details of findings and methods of these studies, it is worth pointing to some of the most clinically significant findings. In one study, 102 young Hispanic children (ages 6–11) who displayed behavior problems were randomized to one of three conditions—structural family therapy, individual psychodynamic therapy, or a recreational control. The first interesting finding was that although BSFT was as effective as individual psychodynamic child therapy, and both treatments were more efficacious than the recreational control in reducing children’s behavioral and emotional problems, there appeared to be a differential impact on family functioning at the 1-year posttermination follow-up (Szapocznik et al., 1989). At this follow-up, the data showed a significant improvement in observer-rated structural family functioning (e.g., structure, conflict resolution, resonance) in BSFT families but showed a significant deterioration in the family functioning of individual psychodynamic child therapy cases. If the hypothesis is correct that symptoms can contribute to family system homeostasis, then child improvement can lead to family disruption, and in some instances deterioration, if the family is not receiving family therapy. Research that includes long-term follow-ups of families may be able to test whether family therapy has its most lasting and meaningful effects in contextual changes that are beyond the reach of individual therapy and most detectable after treatment is completed.

A second study in which 122 African American and Hispanic youth received BSFT produced findings suggesting that BSFT showed promise as an indicated prevention intervention (Santisteban et al., 1997). Although far from conclusive because of the study’s one-group design (not a randomized trial), the data suggest that child behavior problems and poor family functioning were statistically significant predictors of substance use initiation 9 months later, and that BSFT could effectively impact both risk factors for later use. By targeting behavior problems and family problems early (prior to initiation of use), BSFT was in effect a treatment of existing conduct and family problems and indicated prevention of later drug initiation.

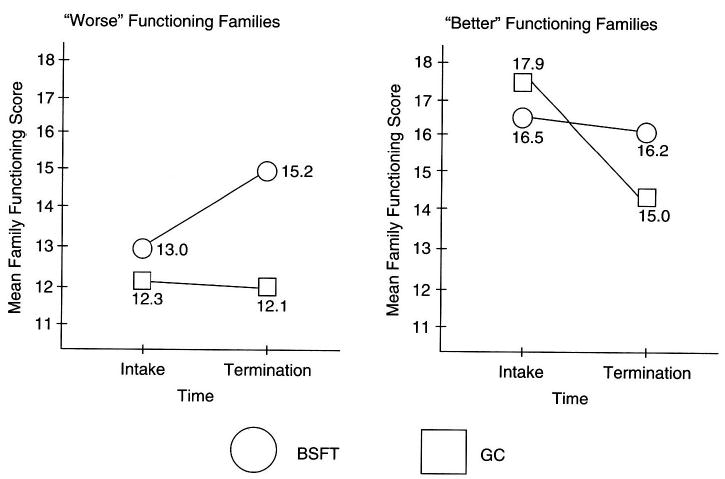

In our most recent study, 126 Hispanic behavior-problem adolescents with substance abuse problems were randomly assigned to either BSFT or group counseling (Santisteban et al., 2003). In this study, two findings were worthy of consideration. The first was that family therapy was significantly more efficacious than the group intervention in reducing conduct problems, associations with antisocial peers, marijuana use, and in improving observer-rated family functioning. The second, and perhaps more interesting, finding was that family changes were found to be associated with changes in behavior problems only for those families who entered treatment with poor family functioning. This may not be surprising given that post-hoc analyses showed how BSFT could only maintain the “good functioning” of families who entered the study doing well as a family, but could actually improve the functioning of families who entered doing “poorly”1 (see Figure 1). This finding raises several important questions regarding different possible therapeutic factors when working with well-functioning versus poorly functioning families. There is much to learn about tailoring family interventions to the profile of the family at intake.

Figure 1.

Changes in Family Functioning (Total SFSR Score) by Time X Condition for Families Entering Treatment with Better and Worse Family Functioning. BSFT = brief strategic family therapy; GC = group control

Despite the interesting questions that remain regarding BSFT and other empirically supported family therapies (e.g., how we best match the specific clinical characteristics of a youth and family to treatment interventions), the body of findings on the overall efficacy of BSFT with youth representing a range of ages and behavior problems has led to the dissemination of this model and tests of its efficacy with more diverse populations. The next section of this article describes major issues that emerge as BSFT and other empirically supported family therapies are transported to frontline drug treatment agencies. In this section, we attempt to identify the facilitators and obstacles to transporting and sustaining family interventions in everyday practice and to maintaining high levels of model adherence.

WORKING WITH NIDA CLINICAL TRIALS NETWORK ON CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION OF EMPIRICALLY SUPPORTED FAMILY TREATMENT

It is now widely acknowledged that the gap that exists between research-proven treatments and clinical practice in many fields is particularly apparent in drug abuse treatment (Institute of Medicine, 1998). For example, despite the evidence for highly efficacious treatments (e.g., methadone maintenance, contingency management) for patients with specific drug dependence problems, there remains remarkably little adoption of these treatments in practice settings (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2003; Rawson, Marinelli-Casey, & Ling, 2002). Some have suggested that it may be particularly difficult to bridge the gap in the treatment of substance abuse because substance abuse counselors and scientists differ in their training, professional identifications, and treatment philosophies (Morgenstern, Morgan, McCrady, Keller, & Carroll, 2001). A second obstacle to the widespread adoption of empirically supported treatment is the need for intensive training and ongoing supervision. Only a sustained effort can ensure that the trainee becomes capable of delivering the new intervention competently. Further, even well-trained practitioners who become competent in a new treatment require the establishment of a system of quality control mechanisms to ensure an adequate level of treatment fidelity in community settings (Schoenwald & Henggeler, 2002). The inability to identify real obstacles to implementation and ongoing fidelity leads to misdiagnosis of provider agencies as lacking interest and motivation to change.

Like other clinical research teams across the country, we have been involved in the movement to bring research-proven interventions to community practitioners. In fact, over the past 2 years, we have provided training in BSFT to over 150 therapists from more than 30 community agencies across the country. In the next section, we describe the NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN), which has become a very productive network for bridging research and practice and has supported several important studies in this area.

NIDA Clinical Trials Network

In our efforts at bridging research and practice, we have had a close collaborative relationship with the NIDA CTN. The CTN was created to bridge the gap between substance abuse research and practice by facilitating intensive collaboration between university-based researchers and community-based clinicians, and by together designing and testing empirically supported treatments in front-line treatment settings. Currently, CTN is comprised of 17 university-based research centers and over 120 community treatment agencies across the country. For this collaborative effort to achieve its intended goal, researchers and providers must jointly determine which clinical treatments would most likely benefit substance abuse patients, and therefore what direction research should take. The intensive working relationship that has been forged in the past 5 years between our research team and Florida’s substance abuse treatment agencies and networks had never been achieved in our 30 years of research on substance abuse in the state. Likewise, the close regional relationships that form around CTN, include state directors, funders of substance abuse treatment, provider associations, addiction technology transfer centers, and policy makers. These strong working relationships help to impact the readiness of decision makers who ultimately determine future funding that can sustain interventions supported by research.

Several characteristics of the CTN clinical research projects have been designed to facilitate the transferability and dissemination of treatment models and techniques. First, the multisite nature of the projects allows for great diversity of patient characteristics in the total sample, including urban versus rural populations, complex psychological profiles (e.g., co-occurring psychiatric disorders), and different ethnic and cultural backgrounds of participants. One example of the CTN achievements is the implementation of a research study that examines the effectiveness of motivational enhancement therapy with substance-using Hispanic adults. With efforts such as this, the CTN is taking steps to address the severe shortage of empirically supported treatments tested with minority populations. A second characteristic that facilitates transferability is that treatment interventions are carried out by community agencies’ own counselors and are supervised on an ongoing basis by clinical supervisors from their own agency. Therefore, the accumulated agency wisdom of how and why things work on the front lines, with diverse patients and in unique funding contexts, is added to the laboratory-derived knowledge of what works and doesn’t work within these protocols.

Testing BSFT in a CTN Multisite Study

Within the CTN, our team has led the development and initiation of a multisite effectiveness study of BSFT for adolescent drug abusers. We believe that this ambitious study represents one of the largest clinical trials of its kind in the field of family therapy for adolescent drug abuse treatment. The CTN-BSFT protocol will randomly assign 480 drug-using adolescents and their families from eight community treatment agencies to BSFT or treatment as usual (usual agency practice). The eight community agencies are set across the United States and Puerto Rico. The widespread implementation of BSFT across different geographical regions will permit the examination of population characteristics (e.g., ethnicity [African American, Hispanic, Caucasian]; severity of drug use), clinic variables (e.g., staff characteristics, size of the clinic, location), and therapist characteristics (e.g., educational level, experience, ethnicity) that may contribute differentially to the success of the intervention. The ethnic and racial diversity of the proposed sample is a strong addition to our program of research. First, it allows for much more work with African American and Caucasian families than our program has ever had. Second, the inclusion of treatment agencies in the west/southwest (e.g., Denver, Los Angeles, and Tucson) and in Puerto Rico extends our work with Hispanics by moving beyond the largely Cuban and Central American samples we have worked with in our previous studies to include a larger proportion of the two largest Hispanic subgroups in the United States, Mexican American and Puerto Rican. Thus, this study provides a unique opportunity for evaluating the generalizability of BSFT to a broader range of families.

The BSFT protocol is currently being implemented at all eight sites. To date, over 150 adolescents and their families have been randomized to BSFT or treatment as usual (i.e., standard agency practices). The major lessons learned to date in this effort and most relevant to this article are lessons concerning the training of “real-world” counselors in BSFT.

Tackling the complex issues of training

An important aspect of this multisite effectiveness trial is the careful attention to the training of therapists.2 Agency counselors are trained by the model developers or credentialed trainers of a particular intervention using CTN or model developers’ training mechanisms. In our effectiveness trial of BSFT, only minimal screening of therapists is conducted. This screening ensures that therapists have adequate interpersonal skills, are able to interact with different family members, and are open to learning an intervention that is potentially dramatically different from their preferred paradigms for treatment. The biggest challenge in the CTN-BSFT study is to take therapists with little exposure to family therapy prior to selection and help them reach the level of certification in the BSFT model. To accomplish this goal, therapists assigned to BSFT participate in an intensive training program focused on the BSFT manualized interventions (Szapocznik, Hervis, & Schwartz, 2003) and proscribed interventions that are inconsistent with BSFT. Over 140 hours of training are provided in four 3-day face-to-face workshops and weekly supervision sessions. Therapists are required to carry two to four active cases/families during training to provide opportunities for implementing and refining model-specific skills. All sessions are videotaped. The videotapes are copied and sent to our training team to facilitate weekly supervision based on direct observation of therapists with families. At the conclusion of training, segments from videotapes are reviewed by a certification panel (composed of three experts in BSFT) to determine if the therapist has achieved competency in all the key domains of BSFT (e.g., joining, reframing, and restructuring interactions). During the implementation phase of the trial, at least one videotape from every therapist is rated for adherence using an adherence checklist, and therapists also participate in a weekly group supervision session. Although working with tapes creates many logistical and fiscal challenges, we believe that direct observations of family interactions and therapist maneuvers is essential for trainers and supervisors to effectively monitor therapist progress. In training therapists at community agencies, we have identified a number of factors that are critical to the successful training of therapists in BSFT. These factors can be conceptualized at three levels: the agency, the therapist, and the supervision process.

At the level of the agency, we have found, without exception, that the context in which therapists work is directly related to the success of training. Agencies that understand and that are committed to the training process are more likely to have therapists who succeed than agencies that do not understand or that are not committed to intensive training. This commitment must start at the top and must translate into providing time and support to therapists for their participation in workshops, weekly supervision sessions, and implementation of BSFT with families. For example, the level of effort involved in engaging and working with families (rather than the adolescent alone) involves adjusting therapists’ caseloads accordingly. Therapists from agencies that do not provide these concrete indicators of support have a much more difficult time getting certified.

A number of factors are important at the level of the therapist. Although extensive experience is not required, we have found that therapists who start with more skills are easier to train. However, we also have found that a commitment to learn a new model and to work with families is probably as important as prior family therapy experience. This commitment must be consistent over time. Therapists who miss supervision sessions or workshops and who do not spend time preparing for sessions or reviewing prior videotapes are less likely to succeed in training. Although we do not yet have empirical evidence to support our assumptions, we believe that therapists that understand systems and organizations will have an easier time implementing BSFT. For this reason, we spend considerable time training, presenting, and reviewing systemic principles, both in general and in specific reference to BSFT. Nonetheless, conceptual skills alone are not enough. Therapists must have opportunities to practice new skills with real families. Therapists who see fewer families during training take much longer to get certified (and in many cases do not get certified) than therapists who work with many families. At a minimum, we recommend that a therapist work with four families during training.

Finally, aspects of the supervision process also contribute to the success of training. Supervisors who are able to foster a sense of teamwork among therapists at an agency and who are viewed by therapists as supportive and directive are more likely to succeed in bringing therapists to certification than supervisors who have a difficult time creating this context. It should be noted that the formation of this supportive team context starts at the highest levels, both at the agency and in the Center for Family Studies’ Training Institute. If therapists or the supervisor are not supported in this effort within their own agency, the formation of a clinical supervision team will likely be negatively affected. Supervisors also need to tailor their training strategies to different individuals and groups. In one group (or for one therapist), supervisors may need to be highly directive and active, providing concrete guidance and recommendations throughout training, whereas for other therapists, the supervisor may be more effective by adopting a less directive or active position. With respect to the latter, for example, therapists may learn more quickly by generating ideas and solutions on their own rather than having the supervisor generate all recommendations. Supervisors must also have the time to review videotapes of therapy sessions and case notes for each therapist every week. The integration of observation and case review in supervision provides the supervisor with different sources of information that may be complementary or contradictory. In either case, the supervisor can develop tailored recommendations for therapists based on this information.

Although we can only report on our training experiences to date, we are also empirically examining the training process and training outcomes. Therapists’ characteristics prior to training (e.g., professional experience, recovery status, theoretical orientation) and their conceptualization and implementation of BSFT will be examined to identify those factors that predict BSFT skill-acquisition trajectories. Training of front-line service providers remains one of the most challenging processes to widespread adoption of empirically supported treatments. Research efforts designed to learn more about this key process are needed in the field.

CONCLUSIONS

In this article, we have described the important role that family therapy can play in adolescent substance abuse treatment and in addressing the unique needs of Hispanic families. Our findings point to the efficacy of both family-based engagement and treatment interventions. In addition to answering questions regarding impact on outcome variables, we have described other important findings that mirror the types of challenges clinicians face daily (e.g., how one tailors a family therapy to the specific needs of the family). For example, our work has suggested that we do not yet know what types of therapeutic changes may be most significant for families who enter treatment with relatively good family functioning.

In addition, it must be acknowledged that the severe shortage of empirically supported treatments for Hispanics with substance abuse problems is bound to result in poor treatment for Hispanics. Some may decide to use empirically supported treatments that have not been adequately tested with Hispanics, while others may choose to shy away from treating Hispanics altogether, using the misguided reasoning that empirically supported treatments are nonexistent. Although the focus of this article has been on the dissemination of empirically supported treatments, we cannot fail to acknowledge this larger dilemma in the field and the highly negative consequences that it may have.

To introduce answer the next generations of research questions concerned with effectiveness, we have also presented some of the major challenges to adoption of empirically supported treatments, the contributions to the field of the NIDA Clinical Trials Network, and the opportunities that this network has provided to our research team and others around the country. The fields of mental health and substance abuse treatment are likely to make significant and sustained advances only if we continue to conduct research that can allow us to empirically address several key questions. One major question revolves around the most effective structure and process for dissemination. The number of published articles reporting on randomized trials that test competing strategies for training and dissemination is insignificant. The field needs to identify empirically supported dissemination methods and strategies. A second question that must be addressed involves the types of focused supervision and monitoring for fidelity needed by front-line providers to truly adopt and sustain empirically supported treatments and to maintain the types of effect sizes reported in efficacy studies. A third critical question focuses on identifying the role of client factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and clinical profiles (e.g., co-occurring psychiatric disorders, family functioning) that may impact treatment responsiveness. Although past efforts to match client characteristics with specific treatments have not been fruitful, there is much yet to be tested.

Footnotes

This work was funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant No. 1 RO1 DA 13104, Developing a Culturally-Rooted Adolescent Family Therapy, Daniel A. Santisteban, Ph.D., principal investigator; and Grant No. 1U10DA 13720, Florida Node of the Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network, José Szapocznik, Ph.D., principal investigator.

Group counseling resulted in deterioration in the family functioning of youth who entered the study with “good functioning” and failed to improve the functioning of families who entered doing “poorly.”

It should be noted that although some training programs focus on training of entire agencies (as we do in other efforts), the research design of this study has half the therapists from each agency randomly assigned to delivering BSFT and half assigned to delivering treatment as usual.

References

- Ary DV, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. Adolescent problem behavior: The influence of parents and peers. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 1999;37:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Health care policy, psychotherapy research, and the future of psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 1996;51:1050–1058. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Bridging the gap: A hybrid model to link efficacy and effectiveness research in substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:333–339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot R. The editor’s introduction: A guide to the empirically supported treatments controversy. Psychotherapy Research. 1998;8:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov, C.E. (2003). Culture in family therapy: New variations on a fundamental theme. In T.L. Sexton, G. Weeks, & M.S. Robbins (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy (pp. 37–58). New York: Brunner Routledge.

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB. A development-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2000;16:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, J. (1976). Problem-solving therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hengeller, S.W., Schoenwald, S.K, Borduin, C.M., Rowland, M.D., & Cunningham, P.B. (1998). Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.

- Institute of Medicine. (1998). Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. [PubMed]

- Lamb, S., Greenlick, M.R., & McCarty, D. (Ed.) (1998). Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed]

- Liddle, H.A. (2002). Multidimensional family therapy treatment (MDFT) for adolescent cannabis users. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Marital conflict, family processes, and boys’ externalizing behavior in Hispanic American and European American families. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:12–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber, R., Farrington, D.P., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Van Kammen, W.B. (1998). Multiple risk factors for multiproblem boys: Co-occurrence of delinquency, substance abuse, attention deficit, conduct problems, physical aggression, covert behavior, depressed mood, and shy/withdrawn behavior. In R. Jessor (Ed.), New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior (pp. 90–149). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Marin, G. (1993). Influence of acculturation on familism and self-identification among Hispanics. In M.E. Bernal & G.P. Knight (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation among Hispanics and other minorities (pp. 181–196). Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Minuchin, S., & Fishman, H.C. (1981). Family therapy techniques. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-guided cognitive-behavioral therapy training: A promising method for disseminating empirically supported substance abuse treatments to the practice community. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Ling W. Dancing with strangers: Will U.S. substance abuse practice and research organizations build mutually productive relationships? Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:941–949. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, M.S., Schwartz, S., & Szapocznik, J. (2003). Structural ecosystems therapy with Hispanic adolescents exhibiting disruptive behavior disorders. In J. Ancis (Ed.), Culturally responsive interventions for working with diverse populations and culture-bound syndromes (pp. 71–99). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Schwartz SJ, LaPerriere A, et al. The efficacy of brief strategic/structural family therapy in modifying behavior problems and an exploration of the mediating role that family functioning plays in behavior change. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:121–133. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Perez-Vidal A, Mitrani V, Jean-Gilles M, Szapocznik J. Brief structural strategic family therapy with African American and Hispanic high risk youth: A report of outcome. Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:453–471. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, D.A., Mena, M.P., & Suarez-Morales, L. (2006). Using treatment development methods to enhance the family-based treatment of Hispanic adolescents. In H. Liddle & C. Rowe (Eds.), Adolescent substance abuse: Research and clinical advances (pp. 449–470). Boston: Cambridge University Press.

- Santisteban, D., Muir-Malcolm, J.A., Mitrani, V.B., & Szapocznik, J. (2002). Integrating the study of ethnic culture and family psychology intervention science. In H. Liddle, D.A. Santisteban, R. Levant, & J. Bray (Eds.), Family psychology: Science based interventions (pp. 331–352). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

- Santisteban DA, Szapocznik J. Bridging theory research and practice to more successfully engage substance abusing youth and their families into therapy. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1994;32(2):9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines W, Murray EJ, La Perriere A. Efficacy of interventions for engaging youth/families into treatment and some variables that may contribute to differential effectiveness. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald, S.K., & Henggeler, S.W. (2002). Mental health services research and family based treatment: Bridging the gap. In H. Liddle, R. Levant, D.A. Santisteban, & J. Bray (Eds.), Family psychology: Science based interventions (pp. 259–282). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

- Sexton, T.L., & Robbins, M.S. (2005, June). Family-based intervention programs for adolescent drug problems: Effective change mechanisms, interventions programs, and community implementation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Conference on Family Therapy, American Family Therapy Association/International Family Therapy Association, Washington, DC.

- Sexton, T.L., Robbins, M.S., Holliman, A.S., Mease, A., & Mayorga, C. (2003). Efficacy, effectiveness, and change mechanisms in couple and family therapy. In T.L. Sexton, G. Weeks, & M.S. Robbins (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy (pp. 229–262). New York: Brunner Routledge.

- Stanton, D.M., & Heath, A.S. (2004). Family/couples approaches to treatment engagement and therapy. In J.H. Lowinson, P. Ruiz, R.B. Millman, & J.G. Langrod (Eds.), Substance abuse: A comprehensive textbook (4th ed., pp. 680–690). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Szapocznik, J., Amaro, H., Gonzalez, G., Schwartz, S.J., Castro, F.G., & Bernal, G., et al. (2003). Drug abuse treatment for Hispanics. In H. Amaro & D.E. Cortés (Eds.), National strategic plan on Hispanic drug abuse research: From the molecule to the community (pp. 91–117). Boston: National Hispanic Science Network on Drug Abuse, Northeastern University Institute on Urban Health Research.

- Szapocznik, J., Hervis, O.E., & Schwartz, S. (2003). Brief strategic family therapy for adolescent drug abuse (NIH Publication No. 03-4751). NIDA Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Szapocznik, J., & Kurtines, W. (1989). Breakthroughs in family therapy with drug abusing and problem youth. New York: Springer.

- Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Brickman A, Foote FH, Santisteban D, Hervis OE, et al. Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families into treatment: A strategic structural systems approach. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:552–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Rio AT, Hervis OE, Mitrani VB, Kurtines WM, Faraci AM. Assessing change in family functioning as a result of treatment: The structural family systems rating scale (SFSR) Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 1991;17:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Rio A, Murray E, Cohen R, Scopetta MA, Rivas-Vasquez A, et al. Structural family versus psychodynamic child therapy for problematic Hispanic boys. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:571–578. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Scopetta MA, Aranalde MA, Kurtines WM. Cuban value structure: Clinical implications. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:961–970. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]