Abstract

Superoxide dismutase cofactored by copper and zinc ([Cu,Zn]-SOD) contributes to the protection of opsonized serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis against phagocytosis by human monocytes/macrophages, with sodC mutant organisms being endocytosed in significantly higher numbers than are wild-type organisms. The influence of [Cu,Zn]-SOD was found to be exerted at the stage of phagocytosis, rather than at earlier (modulating surface association) or later (intracellular killing) stages.

Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are metalloenzymes that catalyze the conversion of superoxide radical anions to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen by removing key substrates for the formation of highly reactive, toxic small molecules such as peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radical (13, 19). There are three classes of SODs in bacteria. Manganese- and iron-cofactored SODs are found in the cytosol, while members of the third class of bacterial SODs—those cofactored by copper and zinc ([Cu,Zn]-SODs; encoded by sodC)—are located in the periplasm or are lipid anchored in the outer envelope (4, 5, 10, 11, 21, 28). In such a location, [Cu,Zn]-SOD can dismutate superoxide produced outside the bacterial cell by the action of phagocytic cells, for example, and so contribute to bacterial virulence (6, 7, 16, 20, 27).

Neisseria meningitidis, a common colonist of the human upper respiratory tract, occasionally invades the epithelium by transcytosis (15) and proliferates in the bloodstream to cause life-threatening septicemia and meningitis in previously healthy children. [Cu,Zn]-SOD protects meningococci from the toxicity of exogenous superoxide generated by the oxidation of xanthine in vitro (8), and sodC mutants are significantly attenuated in a systemic mouse model of meningococcal infection (27). [Cu,Zn]-SOD has been shown to contribute to the survival of bacteria within nonprofessional phagocytes (2), so we have hypothesized that sodC contributes to the pathogenic potential of N. meningitidis by conferring resistance to bactericidal mechanisms based on the production of reactive oxygen intermediates that operate against bacteria in the circulation. Here we report the results of our investigation into the interaction of isogenic wild-type bacteria and sodC mutants with fresh human monocytes/macrophages, showing that meningococcal [Cu,Zn]-SOD enhances the capacity of bacteria to avoid internalization by these important contributors to host defense.

The serogroup B meningococcal strain MC58 and its nonencapsulated mutant MC58¢2, created by a defined deletion in the capsulation locus, were kindly provided by Mumtaz Virji, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom (26). The sodC mutant of MC58 has been described previously (27). A sodC mutant of MC58¢2 was constructed by using plasmid pJSK207, which contains the sodC gene interrupted by a kanamycin cassette, as described by Wilks et al. (27). All experiments were performed with bacteria that had been subcultured once only. The comparative amounts of the surface components B capsule, nonsialylated lipopolysaccharide (LPS), pilin, and the class 5 proteins Opc and Opa were determined semiquantitatively by dot blotting (24) with antibodies against serogroup B capsule (29), nonsialylated LPS (L8; monoclonal antibody [MAb] SM82 [22]), pilin (MAb SM1 [23]), Opc (MAb 306 [1]), and Opa (MAb B33 [12]). All meningococcal strains expressed comparable levels of Opc, Opa, and pilin. As expected, none of the strains bound SM82, implying that the strains were all expressing a sialylated LPS immunotype. MC58 and the MC58 sodC mutant had comparable levels of serogroup B capsule, while MC58¢2 and the MC58¢2 sodC mutant had none (data not shown). For opsonization of meningococci, a stock of pooled human serum (PHS) was isolated from clotted blood samples that had been collected from adult laboratory volunteers and then immediately frozen at −70°C. None of these individuals had received any meningococcal vaccine other than the serogroup C polysaccharide vaccine, which is irrelevant in this context. The meningococci were suspended in RPMI medium containing 7.5% PHS at a density of 108/ml and gently agitated on a slow orbital rotator at 37°C for 10 min. Opsonized bacteria were isolated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed in RPMI medium, and suspended in RPMI medium containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum for use in experiments. To obtain nonopsonized meningococci for use in paired experiments, the bacteria were treated in the same way, with the omission of PHS from the incubation mixture. In an immunodot blot assay with titration, anti-human immunoglobulin G and anti-human C3 antibodies bound to lysates of opsonized meningococci (all strains) to similar levels (data not shown).

In order to measure meningococcal association with human monocytes, monolayers were established as described by McNeil et al. (14). Preparations routinely consisted of >99% mononuclear cells, as verified by Turks staining, and viability (assessed by trypan blue exclusion) was >99%. Monolayers of monocytes (105/well) were incubated with meningococci (107/well) at a bacterium/monocyte infection ratio of 100:1 for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, the monocytes were washed three times with RPMI medium to remove unassociated bacteria and lysed with 1% saponin (which is nontoxic to meningococci under the experimental conditions employed [25]) and the bacteria were enumerated. Opsonized encapsulated N. meningitidis organisms associated with mononuclear cells in substantially higher numbers than did nonopsonized encapsulated bacteria, although not in such high numbers as did the nonencapsulated mutants. On average, the numbers of opsonized encapsulated meningococci and nonopsonized nonencapsulated meningococci that associated with monocytes were about 4.5 × 104/well and 1 × 106/well, respectively. SodC expression had no detectable effect on association with mononuclear cells (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Interaction of opsonized, encapsulated N. meningitidis organisms with monocytesa

| Expt |

sodC mutant/sodC+ organism ratio

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Associationb | Uptakec | |

| 1 | 0.89 | 1.79 |

| 2 | 1.88 | 2.55 |

| 3 | 1.77 | 4.92 |

| 4 | 1.37 | 3.59 |

| 5 | 1.02 | 8.78 |

| 6 | 1.23 | 3.10 |

| 7 | 0.98 | 5.35 |

| 8 | 1.60 | 4.54 |

| 9 | 3.30 | 5.84 |

The ratios of numbers of sodC mutant/sodC+ meningococci associating with, and taken up by, monocytes (i.e., bacterium/monocyte ratio) are shown for nine independent experiments.

Mean ± standard error of the mean, 1.56 ± 0.25.

Mean ± standard error of the mean, 4.50 ± 0.7.

Protection of intracellular meningococci against the bactericidal effect of gentamicin was exploited to enumerate internalized organisms by selective removal of bacteria attached to the cell surface (14, 24). Monocytes were incubated with meningococci for 1 h and then washed three times with RPMI medium to remove unassociated bacteria. The wells were then filled with RPMI medium containing 200 μg of gentamicin per ml and incubated for 50 min to eliminate extracellular bacteria (preliminary experiments showed that all bacteria, both encapsulated and nonencapsulated as well as sodC-positive and sodC-negative phenotypes, were equally sensitive to gentamicin). Monocytes were then washed and subjected to saponin treatment as described above, and the bacteria were enumerated. To confirm that the bacteria surviving at the end of the experiment had indeed been within the monocytes, in parallel experiments cytochalasin D (2 μg/ml) was added at the outset to inhibit the phagocytic uptake of bacteria, as described by Virji et al. (23). In the presence of this inhibitor, very few bacteria (<1% of the number found otherwise) survived the gentamicin incubation stage (data not shown).

Opsonized encapsulated N. meningitidis organisms were found within mononuclear cells in substantially higher numbers than nonopsonized encapsulated bacteria were but not in as high numbers as were the nonencapsulated isogenic mutants. In contrast to our finding relating to bacterial association, sodC expression did significantly affect phagocytosis of opsonized, encapsulated N. meningitidis by monocytes (Table 1). The number of SodC-deficient meningococci internalized by monocytes was 4.5-fold higher than the number of sodC+ meningococci isolated from inside the cells (P < 0.01, two-tailed test). We could not detect any effect of sodC expression on the substantially greater internalization of nonopsonized nonencapsulated bacteria.

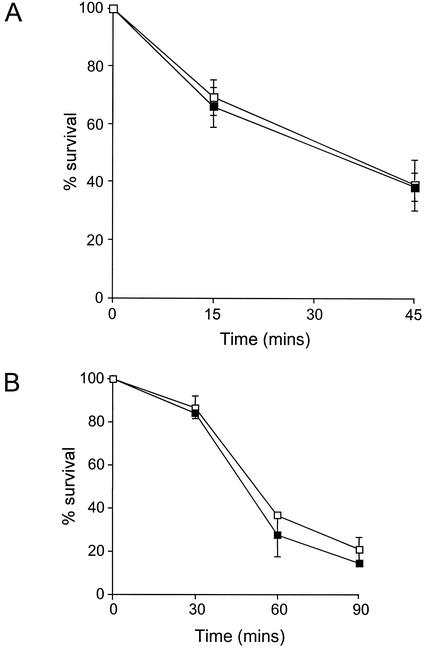

The internalization assay was extended to measure intracellular killing of bacteria. After the stage of gentamicin treatment, the monocytes were washed and incubated for 45 min in RPMI medium containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 20 μg of gentamicin per ml to allow further intracellular killing to occur. The monocytes were then lysed with 1% saponin, and the released intracellular bacteria were enumerated. Killing was expressed as the percent decrease in bacterial CFU over this last period compared with the CFU recovered from cells lysed immediately. Opsonized encapsulated meningococci were killed efficiently: about 60% of the bacteria that were intracellular at the end of the gentamicin incubation had been killed after a further 45-min incubation. sodC+ and sodC mutant organisms were killed inside monocytes at similar rates (Fig. 1A). In these experiments, the mean number of bacteria that were intracellular at time zero was determined to be ∼250 organisms per monolayer (sodC+ organisms) or ∼700 organisms per monolayer (sodC mutant organisms). Data in the figure are represented as percentages of these initial values. In similar experiments, in which nonopsonized nonencapsulated meningococci were used, the rates of intracellular killing of sodC+ and sodC mutant meningococci were also indistinguishable (Fig. 1B). In these experiments, the mean number of bacteria that were intracellular at time zero was in general much higher, i.e.,∼2.7 × 104 organisms per monolayer (sodC+ organisms) or ∼5.4 × 104 organisms per monolayer (sodC mutant organisms). Data in the figure are again represented as percentages of these initial values.

FIG. 1.

Intracellular survival of opsonized encapsulated (A) and nonencapsulated (B) sodC+ (open symbols) and sodC mutant (filled symbols) meningococci in human monocytes. Bacteria were incubated with human monocytes for 1 h, and then extracellular organisms were eliminated by washing and incubation with gentamicin. Intracellular bacteria were enumerated at intervals after the incubation with gentamicin, and the percent survival was determined.

Phagocytosis of meningococci that are opsonized and encapsulated—the phenotype found in the human circulation during meningococcal disease—was found to be attenuated by bacterial expression of sodC, such that the number of sodC mutant meningococci recovered from inside phagocytic cells was four to five times the number of sodC+ organisms that were internalized. The effect was inhibitable by cytochalasin D, indicating that [Cu,Zn]-SOD exerted its effect beyond the stage of bacterium-phagocytic cell association: there was no detectable effect of [Cu,Zn]-SOD on the superficial association of meningococci with host cells.

Considering the possibility that the difference found might be the result of a secondary alteration in the bacterial surface, perhaps because SodC antioxidant activity was necessary to maintain the stability of some antiphagocytic surface component, we examined a range of bacterial surface structures in wild-type and mutant strains. While we cannot rule out the possibility that a low-abundance molecule has been critically altered by mutation of sodC, leaving the organism more susceptible to phagocytosis, there was no detectable difference in the outer membrane profiles of wild-type and sodC mutant meningococci (Sarkosyl- and Triton X-100-insoluble fraction) demonstrated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Wild-type and sodC mutant meningococci expressed similar amounts of capsule, pili, Opa, and Opc, structures that have previously been shown to influence nonopsonic interactions of N. meningitidis with human cells (14, 18, 23-26). sodC expression also did not influence the extent of opsonization of encapsulated N. meningitidis by PHS, as shown by an immunodot blot assay with titration using anti-human immunoglobulin G and anti-human C3 antibodies (data not shown).

While the most straightforward explanation for our recovery of fewer wild-type than sodC mutant meningococci from within phagocytic cells is that wild-type organisms are relatively resistant to phagocytosis, an alternative to be considered is that mutant bacteria might be relatively resistant to killing within host cells. This was ruled out by measuring the rate of bacterial killing after internalization. Over the 45-min period following internalization, 60 to 70% of internalized bacteria were killed, regardless of sodC genotype and regardless of the initial number of bacteria internalized. Our intuitive expectation had been the opposite, i.e., that externally accessible bacterial SOD would promote the survival of bacteria within phagocytic cells through partial quenching of the inferno of small-molecule oxidants produced in the respiratory burst. Such a role has been demonstrated for surface-exposed SOD in Nocardia asteroides and recently for [Cu,Zn]-SOD in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3, 16). If indeed [Cu,Zn]-SOD plays any such role in N. meningitidis, undetected by our relatively insensitive counting assay, then the effect of the enzyme on the totality of phagocytosis and killing is even more pronounced than we have established.

To explain our findings, we hypothesize that [Cu,Zn]-SOD modulates the interaction between meningococci and monocytes/macrophages at the onset of phagocytosis by altering the local concentrations of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide at the phagocytic cell surface. The early release of such reactive oxygen intermediates into the extracellular medium upon activation of phagocytes has been shown to enhance Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis (9, 17). Opsonized meningococci producing periplasmic [Cu,Zn]-SOD are equipped to interfere with the production of those reactive oxygen intermediates, and in doing so, they reduce the stimulus for the phagocyte to increase its phagocytic capacity and remove the bacteria from the circulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant to J.S.K. from The Meningitis Research Foundation.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., M. Neibert, B. Crowe, W. Strittmatter, B. Kusecek, E. Weyse, M. Walsh, B. Slawig, G. Morelli, and A. Moll. 1988. Purification and characterization of eight class 5 outer membrane protein variants from a clone of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A. J. Exp. Med. 168:507-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battistoni, A., F. Pacello, S. Folcarelli, M. Ajello, G. Donnarumma, R. Greco, M. G. Ammendolia, D. Touati, G. Rotilio, and P. Valenti. 2000. Increased expression of periplasmic Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase enhances survival of Escherichia coli invasive strains within nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 68:30-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaman, L., and B. L. Beaman. 1990. Monoclonal antibodies demonstrate that superoxide dismutase contributes to protection of Nocardia asteroides within the intact host. Infect. Immun. 58:3122-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck, B. L., L. B. Tabatabai, and J. E. Mayfield. 1990. A protein isolated from Brucella abortus is a Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry 29:372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Orazio, M., S. Folcarelli, F. Mariani, V. Colizzi, G. Rotilio, and A. Battistoni. 2001. Lipid modification of the Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. J. 359:17-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang, F. C., M. A. DeGroote, J. W. Foster, A. J. Baumler, U. Ochsner, T. Testerman, S. Bearson, J. C. Giard, Y. Xu, G. Campbell, and T. Laessig. 1999. Virulent Salmonella typhimurium has two periplasmic Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7502-7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrant, J. L., A. Sansone, J. R. Canvin, M. J. Pallen, P. R. Langford, T. S. Wallis, G. Dougan, and J. S. Kroll. 1997. Bacterial copper- and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutase contributes to the pathogenesis of systemic salmonellosis. Mol. Microbiol. 25:785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fridovich, I. 1970. Quantitative aspects of the production of superoxide anion radical by milk xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 245:4053-4057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gresham, H. D., J. A. McGarr, P. G. Shackelford, and E. J. Brown. 1988. Studies on the molecular mechanisms of human Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Amplification of ingestion is dependent on the generation of reactive oxygen metabolites and is deficient in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease. J. Clin. Investig. 82:1192-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroll, J. S., P. R. Langford, and B. M. Loynds. 1991. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Haemophilus influenzae and H. parainfluenzae. J. Bacteriol. 173:7449-7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroll, J. S., P. R. Langford, K. E. Wilks, and A. D. Keil. 1995. Bacterial [Cu,Zn]-superoxide dismutase: phylogenetically distinct from the eukaryotic enzyme, and not so rare after all! Microbiology 141:2271-2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli, C. J., A. E. Karu, and G. F. Brooks. 1988. Antigenic specificity and biological activity of a monoclonal antibody that is broadly cross-reactive with gonococcal proteins IIs, p. 737-743. In J. T. Poolman, H. C. Zanen, T. F. Meyer, J. E. Heckels, P. R. H. Makela, H. Smith, and E. C. Beuvery (ed.), Gonococci and meningococci. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 13.McCord, J. M., and I. Fridovich. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244:6049-6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeil, G., M. Virji, and E. R. Moxon. 1994. Interactions of Neisseria meningitidis with human monocytes. Microb. Pathog. 16:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merz, A. J., and M. So. 2000. Interactions of pathogenic neisseriae with epithelial cell membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:423-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piddington, D. L., F. C. Fang, T. Laessig, A. M. Cooper, I. M. Orme, and N. A. Buchmeier. 2001. Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis contributes to survival in activated macrophages that are generating an oxidative burst. Infect. Immun. 69:4980-4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pricop, L., J. Gokhale, P. Redecha, S. C. Ng, and J. E. Salmon. 1999. Reactive oxygen intermediates enhance Fc gamma receptor signaling and amplify phagocytic capacity. J. Immunol. 162:7041-7048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Read, R. C., S. Zimmerli, V. C. Broaddus, D. A. Sanan, D. S. Stephens, and J. D. Ernst. 1996. The (α2→8)-linked polysialic acid capsule of group B Neisseria meningitidis modifies multiple steps during interaction with human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 64:3210-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reif, A., L. Zecca, P. Riederer, M. Feelisch, and H. H. Schmidt. 2001. Nitroxyl oxidizes NADPH in a superoxide dismutase inhibitable manner. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30:803-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansone, A., P. R. Watson, T. S. Wallis, P. R. Langford, and J. S. Kroll. 2002. The role of two periplasmic copper- and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutases in the virulence of Salmonella choleraesuis. Microbiology 148:719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St. John, G., and H. M. Steinman. 1996. Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Legionella pneumophila: role in stationary-phase survival. J. Bacteriol. 178:1578-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virji, M., and J. E. Heckels. 1988. Nonbactericidal antibodies against Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evaluation of their blocking effect on bactericidal antibodies directed against outer membrane antigens. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2703-2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virji, M., H. Kayhty, D. J. Ferguson, C. Alexandrescu, J. E. Heckels, and E. R. Moxon. 1991. The role of pili in the interactions of pathogenic Neisseria with cultured human endothelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1831-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, D. J. Ferguson, M. Achtman, and E. R. Moxon. 1993. Meningococcal Opa and Opc proteins: their role in colonization and invasion of human epithelial and endothelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 10:499-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, D. J. Ferguson, M. Achtman, J. Sarkari, and E. R. Moxon. 1992. Expression of the Opc protein correlates with invasion of epithelial and endothelial cells by Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2785-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, I. R. Peak, D. J. Ferguson, M. P. Jennings, and E. R. Moxon. 1995. Opc- and pilus-dependent interactions of meningococci with human endothelial cells: molecular mechanisms and modulation by surface polysaccharides. Mol. Microbiol. 18:741-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilks, K. E., K. L. R. Dunn, J. L. Farrant, K. M. Reddin, A. R. Gorringe, P. R. Langford, and J. S. Kroll. 1998. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase in meningococcal pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 66:213-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu, C. H., J. J. Tsai-Wu, Y. T. Huang, C. Y. Lin, G. G. Lioua, and F. J. Lee. 1998. Identification and subcellular localization of a novel Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS Lett. 439:192-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zollinger, W. D., J. Boslego, L. O. Froholm, J. S. Ray, E. E. Moran, and B. L. Brandt. 1987. Human bactericidal antibody response to meningococcal outer membrane protein vaccines. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 53:403-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]