Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO·) produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is an important host defense molecule against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mononuclear phagocytes. The objective of this study was to determine the role of the IκBα kinase-nuclear factor κB (IKK-NF-κB) signaling pathway in the induction of iNOS and NO· by a mycobacterial cell wall lipoglycan known as mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan (ManLAM) in mouse macrophages costimulated with gamma interferon (IFN-γ). NF-κB was activated by ManLAM as shown by electrophoretic mobility shift assay, by immunofluorescence of translocated NF-κB in intact cells, and by a reporter gene driven by four NF-κB-binding elements. Transduction of an IκBα mutant (Ser32/36Ala) significantly inhibited NO· expression induced by IFN-γ plus ManLAM. An activated SCF complex, a heterotetramer (Skp1, Cul-1, β-TrCP [F-box protein], and ROC1) involved with ubiquitination, is also required for iNOS-NO· induction. Two NF-κB-binding sites (κBI and κBII) present on the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter bound ManLAM-induced NF-κB similarly. By use of reporter constructs in which one or both sites are mutated, both NF-κB-binding positions were essential in iNOS induction by IFN-γ plus ManLAM. IFN-γ-induced activation of the IRF-1 transcriptional complex is a necessary component in host defense against tuberculosis. Although the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter contains an NF-κB-binding site and ManLAM-induced NF-κB also binds to this site, ManLAM was unable to induce IRF-1 expression. The influence of mitogen-activated protein kinases on IFN-γ plus ManLAM induction of iNOS-NO· is not due to any effects on ManLAM induction of NF-κB.

In response to cytokines or pathogen-derived molecules, nitric oxide (NO·) and other reactive nitrogen intermediates derived from the catalytic action of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) play an important role against a variety of intracellular microbes including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1, 17, 26, 31, 43). In the murine model of tuberculosis (TB), NO· is essential for the killing (or at least growth limitation) of the tubercle bacilli by mononuclear phagocytes (16, 17, 46, 60). Although the precise function of NO· in human TB is controversial, there is a growing body of evidence that NO· and related reactive nitrogen species are also important in humans (33, 40, 51, 52, 57, 58, 68).

Innate immune cells can be activated through recognition of pathogen-derived molecules such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipopeptides, lipoteichoic acid, and DNA CpG motifs (59). The cell wall lipoglycan of M. tuberculosis, mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan (ManLAM), has pleiotropic functions that include promoting phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis (61), inducing tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and IL-8 production, and inhibiting antigen processing by antigen-presenting cells (2, 7, 18, 20, 25, 49, 61, 64, 74, 75). We previously showed that combined stimulation of a murine macrophage cell line with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and ManLAM induced iNOS expression and NO· production (13). The synergistic role of IFN-γ is due to its ability to induce the expression of Stat1α and IFN-γ-response factor-1 (IRF-1), transcriptional complexes that can also bind to the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter. Furthermore, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways played important regulatory roles in this induction (13). Specifically, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) enhanced IFN-γ-plus-ManLAM-stimulated iNOS-NO· induction whereas p38mapk inhibited such induction.

Another intracellular signaling cascade shown to regulate many host inflammatory mediators is the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway. NF-κB comprises a group of dimeric transcription factors that belong to the Rel protein family, of which there are five members (reviewed in reference 38): RelA, c-Rel (p65), RelB, p50, and p52. Heterodimers that contain RelA or c-Rel, of which c-Rel-p50 is the most illustrious, are basally sequestered in the cytoplasm bound to the inhibitory molecule IκBα. Following sequential activation of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) and the β subunit of the IκBα kinase (IKK) complex (IKK is comprised of α, β, and γ subunits), IKKβ phosphorylates serine 32 and 36 residues in the amino-terminal portion of IκBα, followed by ubiquitination and targeted degradation of IκBα by proteosomes (5). Once liberated, activated NF-κB translocates into the nucleus, binds to specific target DNA elements, and enhances gene expression (6). In contrast, the RelB-p52 heterodimer is regulated differently in that its RelB-p100 polypeptide precursor is degraded by IKKα, releasing active RelB-p52, which translocates into the nucleus (38). Although not as well characterized, translocated NF-κB may undergo further modifications such as phosphorylation to further enhance its trans-activating potential (38). The importance of NF-κB in host defense against microbial pathogens was recently shown by Yamada and coworkers (71), in that p50-NF-κB subunit knockout mice infected with aerosolized M. tuberculosis had significantly decreased cytokine expression, increased mycobacterial burdens in the lungs and spleen, and a marked decrease in the survival rate compared to the C57BL/6 wild-type mice. Since NF-κB is essential in regulating the expression of many genes that are relevant to host defense, we consider it important to further characterize its role in the regulation of iNOS-NO· by IFN-γ plus ManLAM.

Mice with a genetic disruption of the IRF-1 gene are also more susceptible to TB (21, 36, 54). This may be due, in part, to the requirement of IRF-1 in iNOS regulation (reviewed in reference 54). Since the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter also contains an NF-κB-binding element, we queried whether IRF-1 could also be regulated by ManLAM. We hypothesized that NF-κB would directly regulate ManLAM-induced iNOS and IRF-1 expression. Herein, we show that ManLAM activates NF-κB and that IKK-NF-κB and ubiquitination pathways regulate IFN-γ plus ManLAM-induction of iNOS-NO·. In addition, we identified the specific NF-κB-binding cis-regulatory elements upstream of the iNOS promoter that are responsible for this induction. In contrast, although ManLAM-induced NF-κB was capable of binding to the κB element on the IRF-1 promoter region, it was unable to induce IRF-1 protein expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

RAW 264.7γNO(−) macrophages were used for all of the studies (50). Unlike parental RAW 264.7 cells, RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells do not respond to IFN-γ stimulation alone with regard to iNOS-NO· expression, which we considered important in studying signaling pathways induced by ManLAM. ManLAM was isolated as previously described (19) and kindly provided by John Belisle and Patrick Brennan, Colorado State University, Fort Collins. To remove any potential LPS contamination, ManLAM preparations were passed through a Detoxi-Gel column by using sterile pyrogen-free water, stored in pyrogen-free vials, and reconstituted with a sterile pyrogen-free phosphate buffer solution. Evaluation of bacterial endotoxin was done with the amebocyte lysate assay (E. toxate kit; Sigma). All plasmids used were isolated by an endotoxin-free plasmid isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, Ga., and routinely tested for LPS contamination with levels consistently below 0.005 ng/ml. Enhanced chemiluminescence assay kits were obtained from Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, Ill. Mouse IFN-γ was obtained from R & D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, Minn. A rabbit anti-iNOS polyclonal antibody was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, Calif. Anti-p50 NF-κB, anti-c-Jun, anti-c-Fos, and anti-IRF-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif. The MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 was purchased from New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass. The p38mapk inhibitor SB203580 was purchased from Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif. The JNK inhibitor was purchased from the Alexis Corporation. The NF-κB-secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) plasmid was obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif. The full-length iNOS promoter cloned into the pGL2 basic luciferase reporter gene vector was generously provided by Charles Lowenstein, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md., and Robert Scheinman, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver. The iNOS-luciferase reporter constructs with κB site mutations of either the proximal region I (mut-κBI-iNOS-luc), the distal region II (mut-κBII-iNOS-luc), or both sites (mut-κBI-κBII-iNOS-luc) were generously provided by William Murphy, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kans. The E1A-lacking adenovirus vector (AdV) cloned to a mutant (Ser32/36Ala) IκBα construct (AdV-S32/36A-IκBα), a β-galactosidase construct (AdV-LacZ), or a green fluorescent protein (GFP) construct (AdV-GFP) were gifts from Sonya Flores and Jerry Schaak, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. The LipofectAMINE reagent used for the transfection experiments was purchased from Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md. All other reagents were of the highest purity.

Analysis of NO2− accumulation.

Accumulation of NO2− in culture supernatants was quantified by the method described by Ding et al. (24). Briefly, macrophage monolayers were stimulated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 10 μg of ManLAM/ml for 18 h. One-hundred-microliter aliquots of the culture supernatants were dispensed in duplicate into 96-well plates and were mixed with 100 μl of Greiss reagent composed of 1% (wt/vol) sulfanilamide, 0.1% (wt/vol) naphthylethylenediamine hydrochloride, and 2.5% (vol/vol) H3PO4. A standard curve consisting of 0.1 to 5.0 nmol of NaNO2 per 100-μl sample was prepared in growth medium. After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the absorbances of the wells were quantified at 550 nm in a Biotek Instruments plate reader. The number of cells per well was determined by lysing the cell monolayers with Zapoglobin and quantifying the number of released nuclei with a model ZM Coulter counter.

Western blot analysis.

After nucleus-free lysates were normalized for protein content, the samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described previously (66). The blots were then washed in Tris-Tween-buffered saline (TTBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.6] containing 137 mM NaCl-0.05% [vol/vol] Tween 20), blocked overnight with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk, and probed by the method described by Towbin et al. (66) with a polyclonal iNOS or IRF-1 antibody in 5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) dissolved in TTBS. By using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody, the bound primary antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were cultured at 400,000 cells per ml (4 ml/well) in 6-well polystyrene tissue culture plates. After 24 h of incubation (37°C, 5% CO2), the medium was replenished. After another 24 h of growth, the cells were stimulated with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml at various durations. The medium was then removed, and the cells were resuspended in 2 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/well and transferred into 15-ml conical tubes. The sample-containing tubes were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellets obtained were resuspended in 500 μl of ice-cold buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.80], 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA) containing an antiprotease cocktail [2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.5 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzene sulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), and aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A (each at 10 μg/ml)]. Following a 10-min incubation on ice, 500 μl of additional ice-cold buffer containing 1.2% NP-40 was added to each sample, and the samples were vortexed briefly and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets (containing nuclear protein) were washed twice in the lysis buffer containing the antiprotease cocktail and transferred into microcentrifuge tubes. The pellets were resuspended in an extraction buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM AEBSF, 10 μg (each) of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A/ml, and 0.4 M NaCl. The samples were incubated on ice with gentle mixing for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The nuclear protein-containing supernatants were removed, the nuclear protein concentration in each sample was measured by the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), and the samples were frozen at −70°C until use.

A double-stranded oligonucleotide probe (Promega, Madison, WI) containing an NF-κB-binding region, two separate oligonucleotides corresponding to each of the two NF-κB-binding sites present on the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter, and an oligonucleotide spanning an NF-κB-binding site on the IRF-1 promoter were end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP according to the manufacturer's protocol. For each condition, 2 μg of nuclear protein was incubated at room temperature with 10 fmol of labeled probe in a 20-μl binding reaction mixture containing 20 mM Tris base (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40, 5% glycerol, and 0.8 μg of poly(dI-dC). Supershift experiments were also performed using antibodies specific for the p65 and p50 subunits. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, all samples were separated in a 6% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 29:1) using 250 V of electrical potential. The gel was dried onto Whatman paper and exposed to X-ray film.

Immunocytochemistry.

RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were plated onto baked glass coverslips in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells per plate. After 24 h of growth, the cells were stimulated with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml. After 2 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then fixed with 3% formaldehyde (vol/vol) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were subsequently washed twice with PBS, and 200 μl of 1:50-diluted anti-p50 antibody in PBS containing 10% (vol/vol) donkey serum and 0.075% (wt/vol) saponin was added. After 30 min at room temperature, the cells were washed twice in PBS containing donkey serum and saponin. A 200-μl volume of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-goat antibody (1:100) in PBS-donkey serum-saponin was added to the well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by two washes with PBS-donkey serum-saponin and two washes with PBS. Coverslips were mounted onto slides by using a mounting medium containing 1.5 μg of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vectashield)/ml to counterstain the nuclei.

SEAP assay.

RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were transfected with 2 μg of SEAP plasmid and assayed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech Laboratories). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml for 24 h. At 0 and 24 h, 65 μl of the supernatant from each condition was added to 30 μl of 0.5 M Tris-HCl-0.1% BSA in a 96-well plate and incubated at 65°C for 30 min to inactivate non-SEAP alkaline phosphatases. After the plate was allowed to cool for 2 min, 50 μl of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) was added as a substrate and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to 1 h. The plate was then read at 405 nm.

Transduction of attenuated adenovirus-superrepressor IκBα.

RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were plated at a density of 5 × 106 cells per 24-well plate in RPMI containing 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10% (vol/vol) FBS. After 24 h of growth to ∼30 to 40% confluence, AdV-S32/36A-IκBα was added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30:1. As controls, AdV-GFP and AdV-LacZ were also transduced in other cell samples. After 6 h, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were costimulated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 10 μg of ManLAM/ml for 18 h. The cell culture supernatants were assayed for NO2− accumulation as described above.

Transient transfection and luciferase assay.

RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were plated at a density of 5 × 106 per 6-well plate in RPMI containing 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS. After 24 h of growth to ∼30 to 40% confluence, the cells were transfected with plasmids by using LipofectAMINE as described by the manufacturer's protocol (Gibco BRL) and as previously described (15). Briefly, 0.3 μg of either the wild type iNOS promoter-luciferase (iNOS-luc) plasmid, mut-κBI-iNOS-luc, mut-κBII-iNOS-luc, or mut-κBI-mut-κBII-iNOS-luc was combined with 10 μl of LipofectAMINE reagent and 100 μl of Optimem serum-free medium. The LipofectAMINE-DNA mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Each well was then washed with 2 ml of Optimem serum-free medium and replaced with 1 ml of the LipofectAMINE-DNA mixture. After 5 h of incubation, 1 ml of RPMI containing 20% (vol/vol) FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-l-glutamine, were added to each well. The medium was changed 24 h after transfection, and after an additional 48 h, the cells were stimulated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 10 μg of ManLAM/ml for 8 h. The cells were then washed with PBS, lysed in a luciferase lysis buffer, and assayed for luciferase activity according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega Inc.). The amount of luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentration and reported as fold increase in activity.

Statistical analysis.

Replicate experiments were independent, and summary results presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05. Group means were compared by repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Fisher's least significant difference.

RESULTS

IFN-γ plus ManLAM induction of NO· is not due to LPS contamination.

IFN-γ synergizes with ManLAM to induce iNOS expression and NO· production (Fig. 1A) (13). Although great care was taken to ensure that all the reagents used were LPS free (13), including purification of ManLAM with a polymyxin B-containing column, the addition of 5 μg of polymyxin B/ml to the cell cultures did not affect IFN-γ plus ManLAM-induction of NO2− (data not shown). Nevertheless, since LPS is a potent inducer of NO·, the following confirmatory experiments were performed. First, stimulation of RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 0.009 ng of LPS/ml, an amount of LPS contained in 10 μg of ManLAM/ml, produced no detectable NO2− (Fig. 1B). Second, because binding by LPS to its receptor requires LPS-binding protein present in serum, we compared the ability of IFN-γ plus ManLAM versus IFN-γ plus LPS to induce NO2− expression in 10% FBS versus 0.1% FBS. As expected, there was substantial reduction of NO2− production induced by IFN-γ plus LPS under serum-deprived (0.1% FBS) conditions (Fig. 1C). In contrast, there was abundant expression of NO2− with ManLAM plus IFN-γ stimulation in the presence of either 10% or 0.1% FBS (Fig. 1C). These findings provide evidence that the effects of ManLAM are not due to contaminating LPS.

FIG. 1.

Effects of IFN-γ plus ManLAM induction of NO· are not due to LPS contamination. (A) (Top) RAW264.7γNO(−) cells were either left unstimulated or stimulated with either 10 U of IFN-γ/ml, 10 μg of ManLAM/ml, or both for 18 h, followed by an assay for NO2− in the supernatant. (Bottom) Corresponding immunoblot of the whole-cell lysate for iNOS protein. (B) RAW264.7γNO(−) cells were stimulated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 1 ng of LPS/ml or 10 U of IFN-γ/ml plus 0.009 ng of LPS/ml (the latter being the concentration of LPS contained in 10 μg of ManLAM/ml), followed by an NO2− assay. (C) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were stimulated with either IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus LPS (1 ng/ml) or IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml) in the presence of either 10% FBS or 0.1% FBS in the culture medium. Data shown are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

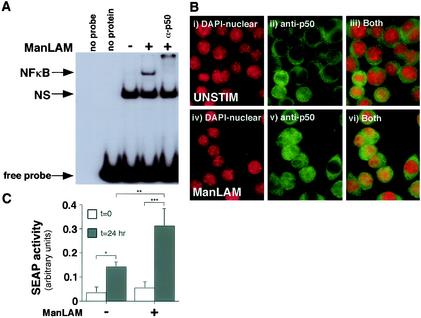

ManLAM activates functional NF-κB.

Three independent approaches were used to determine whether ManLAM was capable of activating NF-κB and whether the induced NF-κB was functional. First, an EMSA was used to detect activated NF-κB by using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe that corresponds to the consensus binding site for NF-κB. As shown in Fig. 2A, there was increased NF-κB activation upon stimulation with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml compared to that in unstimulated cells. Peak activation occurred after 30 min of stimulation (Fig. 2A), although activation was still sustained slightly above basal levels even after 6 h of stimulation (data not shown). The identity of NF-κB was confirmed by the presence of a supershifted NF-κB complex with the addition of a p50 subunit antibody (α-p50).

FIG. 2.

ManLAM activates functional NF-κB. (A) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were stimulated with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 30 min, and nuclear proteins were isolated, followed by an EMSA with a 32P-labeled NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide. Compared to unstimulated cells, ManLAM induced NF-κB activation. The specificity of the NF-κB complex was verified by coincubation of the nuclear extract-oligonucleotide mixture with an anti-p50 antibody (α-p50). The nonspecific (NS) band was present in both unstimulated and ManLAM-stimulated cells and did not supershift with the anti-p50 antibody. (B) Unstimulated and ManLAM-stimulated RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were stained with DAPI for nuclear detection and immunostained with an anti-p50-NF-κB antibody. The cells were then viewed under a fluorescent microscope at selective wavelengths to detect nuclear staining (i and iv), p50-NF-κB staining (ii and v), or both (iii and vi). After counting of 200 cells in random fields, the percentage of cells with positive nuclear staining for p50-NF-κB was 12.5% for unstimulated cells and 46.3% for ManLAM-stimulated cells. (C) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were transfected with 2 μg of the κB-SEAP plasmid. At 0 and 24 h after stimulation with) ManLAM (10 μg/ml), the supernatant was assayed for alkaline phosphatase activity (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Data shown in panels A and B are representative of three independent experiments. Data shown in panel C are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

In the second approach, immunofluorescence of NF-κB in intact unstimulated and ManLAM-stimulated macrophages was examined. As shown in Fig. 2Bi and 2Biv, the nuclei were readily identified with DAPI. In both unstimulated and ManLAM-stimulated cells, p50-NF-κB was detected in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2Bii and 2Bv). In contrast, cells stimulated with ManLAM had increased nuclear localization of p50-NF-κB (Fig. 2B; compare panel ii with panel v and panel iii with panel vi). Quantitatively, the percentages of cells with positive nuclear staining for p50-NF-κB were 12.5% for unstimulated cells and 46.3% for ManLAM-stimulated cells.

To validate that the ManLAM-activated NF-κB was functional, we transiently transfected RAW264.7γNO(−) cells with a SEAP reporter gene (23) that is cloned downstream of four NF-κB-binding cis elements and then stimulated the cells with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml. After an overnight incubation, the supernatants of the cells were measured for alkaline phosphatase activity in a colorimetric assay using PNPP as a substrate (23). As shown in Fig. 2C, there was a modest increase in alkaline phosphatase activity even in unstimulated cells after an overnight incubation. However, in cells stimulated with 10 μg of ManLAM/ml, there was a significant increase in NF-κB-induced alkaline phosphatase activity compared to that in unstimulated cells (**, P < 0.01).

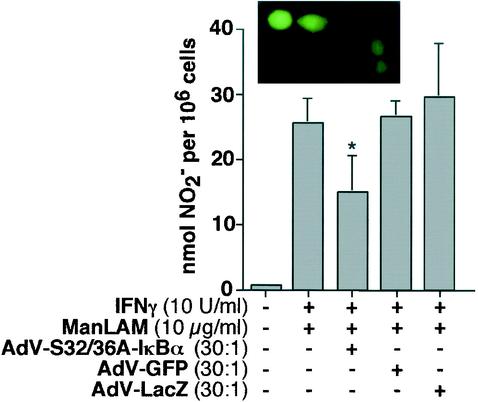

Mutant-IκBα (Ser32/36Ala) inhibits induction of NO· production by IFN-γ plus ManLAM.

Since phosphorylation of IκBα is a prerequisite for NF-κB activation, a dominant-negative IκBα was used to competitively inhibit IκBα phosphorylation and assess its effect on induction of NO· production by IFN-γ plus ManLAM. RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were transduced with an E1A-lacking AdV construct containing a mutant (serine 32/36 alanine) IκBα (S32/36A-IκBα) (22, 34). Due to the lack of E1A, this attenuated AdV-ΔIκBα vector is unable to replicate but remains a potent specific inhibitor of NF-κB activation. Six hours after transduction with AdV-S32/36A-IκBα, or with the control AdV-GFP or AdV-LacZ, the cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 18 h, followed by an assay of the supernatant for NO2−. As shown in Fig. 3, AdV-S32/36A-IκBα modestly but significantly inhibited the level of NO2− accumulation compared to those in the controls AdV-GFP (Fig. 3, inset) and AdV-LacZ.

FIG. 3.

Mutant IκBα inhibits NO· expression. RAW 264.7γNO(−) were transduced with AdV-S32/36A-IκBα, AdV-GFP, or AdV-LacZ at an MOI ratio of 30:1. After 6 h of incubation, the cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 18 h, followed by an assay of the cell supernatant for NO2− (*, P < 0.05). Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (Inset) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells transduced with AdV-GFP and viewed under a fluorescent microscope. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

A dominant-negative protein of Ubc12, an E2 NEDD8-conjugating enzyme, inhibits IFN-γ-plus-ManLAM-induced iNOS promoter activity.

Ubiquitination of IκBα is catalyzed by an E3 ubiquitin ligase called SCF complex, comprising Skp1, Cul-1, β-TrCP (F-box protein), and ROC1 (73). The ubiquitinated IκBα is targeted for proteosome degradation. Importantly, this ubiquitination is regulated by NEDD8 conjugation to Cul-1, a component of the SCF complex. Several groups have shown that the NEDD8 conjugation by the Ubc12 enzyme is essential for the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of the SCF complex (56). To verify whether SCF complex activation is required for activation of iNOS promoter activity by IFN-γ plus ManLAM, we cotransfected the full-length iNOS promoter-luciferase reporter gene (iNOS-luc) with a dominant-negative (cysteine-111 to serine) Ubc12 (C111S-Ubc12) which inhibits NEDD8 conjugation to the Cul-1 subunit (67). RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of the iNOS-luc plasmid and either 2 μg of C111S-Ubc12 or 2 μg of the empty expression vector pcDNA3. After 48 h of growth, the cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 8 h, followed by measurement of luciferase activity in cell lysates and normalization for protein content. As shown in Fig. 4, IFN-γ plus ManLAM stimulation resulted in ∼5-fold induction of luciferase activity in cells transfected with iNOS-luc and the empty vector pcDNA3 (compare first and second bars). Cotransfection of C111S-Ubc12 significantly inhibited induction of iNOS promoter activity by IFN-γ plus ManLAM (Fig. 4, fourth versus second bar; **, P < 0.01).

FIG. 4.

NEDD8 conjugation to Cul-1 is required for IFN-γ plus ManLAM induction of iNOS promoter activity. RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of the iNOS-luc plasmid and 2 μg of the mutant Ubc12 (C111S-Ubc12) plasmid or the empty vector pcDNA3, followed by stimulation with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml). After 8 h of stimulation, nucleus-free lysates were assayed for luciferase activity. Results are reported as fold increase in relative light units (Fold RLU) and normalized for protein concentration. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01 for comparison to second bar from left).

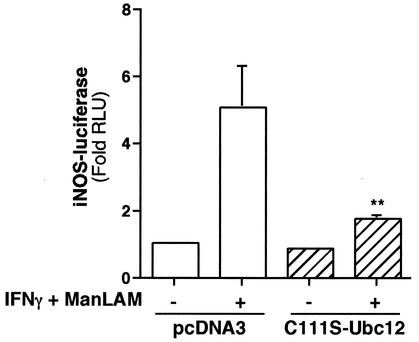

Effects of mut-κBI- and mut-κBII cis-regulatory elements on iNOS promoter activity induced by IFN-γ plus ManLAM.

The 5′-flanking region of the murine iNOS promoter contains two NF-κB-binding sites: an enhancer κB site (κBII) located at −961 to −971 from the transcriptional start site and a basal κB site (κBI) located at −76 to −85 from the start site. In order to determine if one or both of these sites mediate iNOS induction by IFN-γ plus ManLAM, we first examined by EMSA the relative affinity of ManLAM-induced NF-κB for binding each of the NF-κB-binding sites. In an EMSA using 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotides that span each of the sites (CAACTGGGGACTCTCCCTTTGGG for κBI and GCTAGGGGGATTTTCCCTCTCTC for κBII), ManLAM-induced NF-κB bound to each of these sites (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG. 5.

(A and B) Both the basal κBI and the enhancer κBII site on the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter bind ManLAM-induced NF-κB. Macrophages were stimulated with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 30 min, and nuclear protein was isolated and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing either the κBI (A) or the κBII (B) site. As shown, both the κBI and κBII sites bind NF-κB, as confirmed by supershift of the NF-κB-containing complexes with the anti-p50 antibody (α-p50). (C) Stimulation with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) did not induce NF-κB binding to either the κBI or the κBII site. (D) Moreover, neither IFN-γ-induced Stat1α nor IFN-γ-induced IRF-1 bound either NF-κB-binding site, although, as expected, there was binding to GAS and ISRE sites, respectively. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. Slashed circles indicate no nuclear extract in the binding reaction; minus signs indicate unstimulated cells.

Since it was shown that IFN-γ alone may induce NF-κB activation (55), we sought to determine whether IFN-γ can induce NF-κB binding to the κBI and κBII sites contained in the iNOS promoter region. RAW 264.7 cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) for 0.5 to 2 h and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing either the κBI or the κBII site. As shown in Fig. 5C, whereas ManLAM-induced NF-κB bound to these sites, IFN-γ did not induce significant NF-κB binding over basal unstimulated levels (data shown are for the 2-h IFN-γ stimulation). Moreover, neither IFN-γ-induced Stat1α nor IRF-1 bound to the κBI or κBII site (Fig. 5C), whereas, as predicted, Stat1α and IRF-1 bound to IFN-γ-activating sequence(GAS)- and ISRE-containing sequences, respectively (Fig. 5D). The specificity of the Stat1α-GAS oligonucleotide and IRF-1-ISRE complexes were confirmed by supershifting of the respective complexes with an anti-Stat1α antibody (α-Stat1α) and an anti-IFN-stimulated response element (IRF-1) antibody (α-IRF-1), but not with an anti-Stat6 antibody (α-Stat6) (Fig. 5D).

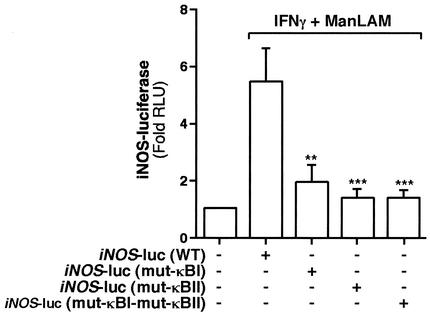

To elucidate the functional significance of each of the κBI and κBII sites, we utilized three distinct mutants of the iNOS-luc reporter construct (50). By site-directed mutagenesis, these constructs have a triplet base substitution of CTC for the wild-type GGG in either one (mut-κBI-iNOS-luc and mut-κBII-iNOS-luc) or both (mut-κBI-mut-κBII-iNOS-luc) of the NF-κB-binding sites (50). We transfected 0.3 μg of either wild-type iNOS-luc (WT-iNOS-luc), mut-κBI-iNOS-luc, mut-κBII-iNOS-luc, or mut-κBI-mut-κBII-iNOS-luc into RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells, followed by stimulation with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 8 h. As shown in Fig. 6, there was a ∼5- to 6-fold increase in luciferase activity with IFN-γ plus ManLAM stimulation and WT-iNOS-luc. By contrast, there was significantly less activity with either the mut-κBI-iNOS-luc or the mut-κBII-iNOS-luc construct (Fig. 6, third versus second bar [**, P < 0.01] and fourth versus second bar [***, P < 0.001]). There was no difference in luciferase activity between the mut-κBI-iNOS-luc and mut-κBII-iNOS-luc constructs (Fig. 6; compare third and fourth bars [P > 0.05]). In addition, there was no further decrease in iNOS promoter activity when both NF-κB-binding sites were mutated (mut-κBI-mut-κBII-iNOS-luc) compared to the individual-site mutations (Fig. 6; compare fifth bar with third or fourth bar [P > 0.05]).

FIG. 6.

Both the basal and enhancer NF-κB-binding sites on the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter are required for IFN-γ plus ManLAM-induction of iNOS. RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were transfected with 0.3 μg of either the iNOS-luc plasmid, the mut-κBI-iNOS-luc plasmid, the mut-κBII-iNOS-luc plasmid, or the mut-κBI-mut-κBII-iNOS-luc plasmid. After 8 h of stimulation with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) plus ManLAM (10 μg/ml), nucleus-free lysates were assayed for luciferase activity. Results are reported as fold-increase in relative light units (Fold RLU) and normalized for protein concentration. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (comparisons to second bar from left).

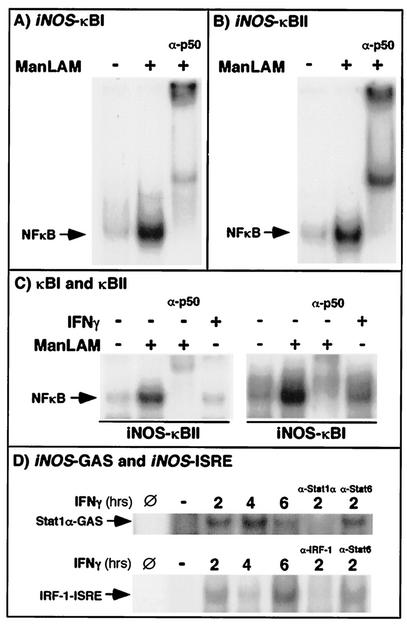

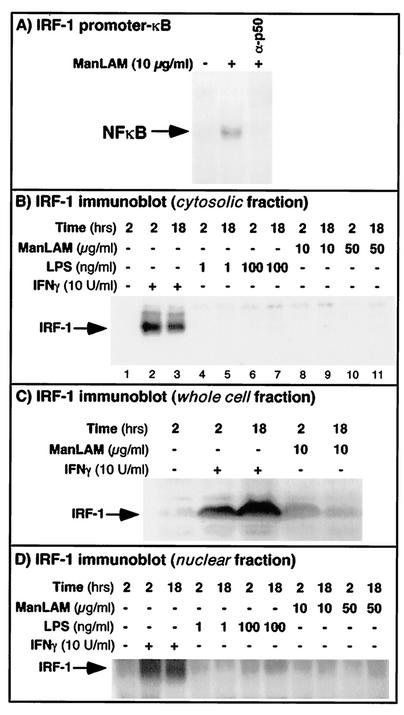

ManLAM-induced NF-κB binds to the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter but appears nonfunctional.

Although IFN-γ is the major inducer of IRF-1, a transactivating factor that plays a synergistic role in iNOS gene transcription, this induction is dependent on IFN-γ-induced Stat1α binding to the IRF-1 promoter region. However, Liu and coworkers (44) showed that in human umbilican vein endothelial cells, LPS was also capable of inducing IRF-1 expression in an NF-κB-dependent fashion. First, to assess whether ManLAM-induced NF-κB can bind to the κB-cis element present on the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter, an oligonucleotide (CCTGATTTCCCCGAAATGA) which spans that element was used in an EMSA. As shown in Fig. 7A, ManLAM-induced NF-κB was able to bind to this site on the IRF-1 promoter region, although the binding was significantly less than that to the κBI and κBII sites on the iNOS promoter (Fig. 5). Second, to ascertain whether ManLAM alone was capable of inducing IRF-1 protein expression, the cells were stimulated with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) at various time points and immunoblotted for IRF-1; as a control, some cells were also stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml), a known potent inducer of IRF-1 expression. As demonstrated in Fig. 7B, compared to that in unstimulated cells, IFN-γ (10 U/ml) induced IRF-1 protein expression as early as 2 h, but expression was sustained even at 18 h. In contrast, no IRF-1 protein was detectable in cells stimulated with either 10 or 50 μg of ManLAM/ml for 2 or 18 h. Additionally, cells stimulated with ManLAM at intervening time intervals of 4, 6, 8, and 12 h did not induce IRF-1 (data not shown). Since these RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells are very sensitive to LPS, a potent inducer of NF-κB, we determined whether IRF-1 protein expression in these cells could be induced by LPS. As shown in Fig. 7B, cells stimulated for 2 or 18 h with LPS at concentrations of 1 or 100 ng/ml also could not induce IRF-1 protein expression.

FIG. 7.

ManLAM-induced NF-κB binds to the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter but does not induce IRF-1 expression. (A) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were stimulated with ManLAM for 30 min, and nuclear extracts were probed with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide that spans the NF-κB-binding site on the 5′-flanking region of the IRF-1 promoter. As shown, ManLAM-induced NF-κB binds to this site and was supershifted with the anti-p50 antibody (α-p50). (B) To determine if ManLAM is capable of inducing IRF-1 expression, the cells were stimulated with either 10 or 50 μg of ManLAM/ml for 2 or 18 h, followed by Western blotting for IRF-1 (lanes 8 to 11). For positive controls, the cells were stimulated with IFN-γ (10 U/ml) for 2 and 18 h (lanes 2 and 3). Since RAW 264.7 cells are quite sensitive to LPS, they were also stimulated with 1 and 100 ng of LPS/ml for 2 and 18 h (lanes 4 to 7). Whereas IFN-γ induced IRF-1 protein expression, neither ManLAM nor LPS did, even at relatively high concentrations. (C) RAW264.7γNO(−) cells stimulated with IFN-γ or ManLAM at the indicated concentrations and times were lysed with Laemmli sample buffer containing 2.5% SDS, which lyses both plasma and nuclear membranes; the lysates were then sonicated for 2 s with a probe sonicator, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for IRF-1. (D) Nuclear proteins were isolated from unstimulated cells and from cells stimulated with IFN-γ, LPS, or ManLAM at the indicated concentrations and times. The nuclear proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for IRF-1.

Since the previously shown immunoblots for IRF-1 were produced with lysates prepared by use of a lysis buffer that did not disrupt the nuclear membranes, and thus would not contain nuclear proteins, we employed two approaches to address the possibility that ManLAM-induced IRF-1 protein may have translocated into the nuclei. In the first approach, unstimulated cells or cells stimulated with IFN-γ or ManLAM were lysed with 1× Laemmli sample buffer containing 2.5% SDS, a detergent which also lyses the nuclear membrane. The resultant DNA-containing tenacious lysates were sonicated for 2 s with a probe sonicator (Sonifier Cell Disruptor; output control setting 6; Heat Systems-Ultronics, Inc., Plainview, N.Y.), and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for IRF-1. As shown in Fig. 7C, there was robust IRF-1 protein expression with IFN-γ stimulation at either 2 or 18 h. The amount of IRF-1 protein induced by ManLAM was significantly less than that with IFN-γ stimulation—slightly above the basal level at 2 h and comparable to unstimulated levels at 18 h of stimulation. In the second approach, nuclear proteins were isolated from unstimulated and IFN-γ- or ManLAM-stimulated cells. The nuclear proteins were then immunoblotted with an anti-IRF-1 antibody. As shown in Fig. 7D, there was minimal IRF-1 protein in unstimulated, LPS-treated, or ManLAM-treated cells at both 2 and 18 h of stimulation; in contrast, there was increased IRF-1 protein expression in the nuclei of IFN-γ-stimulated cells. These experiments confirm that neither LPS nor ManLAM induces much, if any, IRF-1 protein expression over baseline in RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells and that IFN-γ is responsible for the vast majority of IRF-1 induced.

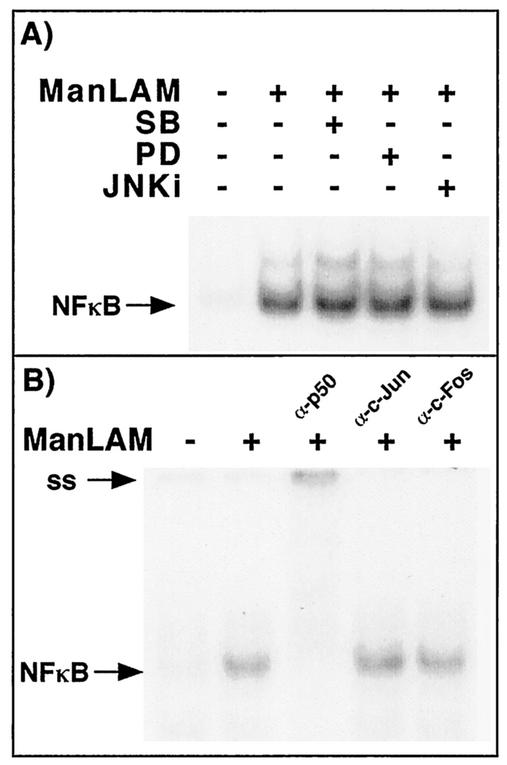

ManLAM activation of NF-κB is unaffected by the MAPKs.

We previously demonstrated that p38mapk inhibited, and ERK enhanced, IFN-γ-plus-ManLAM induction of iNOS-NO· by using the pharmacologic inhibitors MEK1-ERK (PD98059) and p38mapk (SB203580) (13). Since others have shown that various MAPK members may either enhance (8, 10, 32, 37, 72) or inhibit (8, 10, 11, 32) 78 NF-κB activation, we sought to determine whether inhibition of p38mapk, JNK, or MEK1-ERK influenced NF-κB activation. RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were pretreated with either 30 μM PD98059, 30 μM SB203580, the JNK inhibitor at 10 μM, or 0.06% of the vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide for 1 h, followed by stimulation with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 2 h. An EMSA of the isolated nuclear extracts was performed with a 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe that corresponds to the consensus binding site for NF-κB. As shown in Fig. 8A, compared to that in unstimulated cells, there was an increase in NF-κB activation upon stimulation with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) (second versus first lane). In the presence of each of the three MAPK inhibitors, there was no profound difference in ManLAM-induced NF-κB activation (second lane versus third, fourth, and fifth lanes). Each of the MAPK inhibitors was confirmed to inhibit the activity or phosphorylation of its respective MAPK (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

ManLAM-induced NF-κB is unaffected by the MAPKs and does not appear to associate with c-Jun or c-Fos. (A) RAW 264.7γNO(−) cells were either left unstimulated, stimulated with ManLAM (10 μg/ml), or pretreated with PD98059, SB203580, or the JNK inhibitor (JNKi), followed by stimulation with ManLAM (10 μg/ml) for 2 h. Nuclear proteins were isolated, and EMSA was performed on the nuclear extracts by using a 32P-end-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide. (B) The ManLAM-stimulated NF-κB-oligonucleotide complex is supershifted with the p50 antibody but not with either a c-Jun or a c-Fos antibody.

Stein et al. (63) previously showed that c-Jun was able to bind to the p65 component of NF-κB, facilitating binding to the cis-regulatory elements for NF-κB. Since the MAPKs can activate the AP-1 transcriptional complex, typically comprising either a c-Jun homodimer or a c-Jun-c-Fos heterodimer, perhaps c-Jun or c-Fos is bound to the NF-κB complex. However, as shown in Fig. 8B, ManLAM-stimulated NF-κB complexes did not supershift with either a c-Fos or a c-Jun antibody, although the antibodies recognized AP-1 complexes (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The NF-κB signaling pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of human diseases (6). On the other hand, it is also one of the more ubiquitous transcriptional regulatory pathways required for promoting favorable immune and inflammatory responses, particularly in the context of microbial host defense (30). For example, NF-κB has been shown to enhance the expression of molecules that may assist in host defenses, including TNF-α, adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1), IL-8, macrophage metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), the IL-2 receptor, the IL-12 p40 subunit, and iNOS (6, 9, 50, 69). More recently, it was demonstrated that the proinflammatory activity of NF-κB is tightly linked to its ability to prevent the induction of apoptosis initiated by many of the same molecules—such as TNF-α—that it also helps to induce (reviewed in reference 39). This beneficial role of NF-κB in host defense against microbial pathogens is best evinced by the fact that mice with genetic disruption of several of the NF-κB subunits display defects in bacterial and mycobacterial clearance (6, 71). Furthermore, NF-κB is activated in monocytes of tuberculous patients, and purified protein derivative, the tuberculin of M. tuberculosis, induced activation of NF-κB in monocytes in vitro (65).

In this study, we demonstrated by several methods that the IKK-NF-κB pathway was activated by ManLAM and that it was functional. Additionally, NF-κB is essential for IFN-γ-plus-ManLAM-stimulated iNOS induction and NO2− accumulation. Based on experiments with iNOS promoter-luciferase reporter constructs with site-directed mutagenesis of either one or both of the NF-κB-binding sites, both sites were equal requisites for induction of iNOS by IFN-γ plus ManLAM. On the other hand, Murphy and colleagues (50) showed that mutation of the basal κBI element had a quantitatively less dramatic negative effect (∼39% inhibition) on LPS responsiveness than mutation of the enhancer κBII element (∼81% inhibition). Moreover, we found that although ManLAM-activated NF-κB bound to an NF-κB binding site present on the IRF-1 promoter region, it did not induce IRF-1 expression. In our system, the effects of NF-κB were solely mediated by ManLAM, because IFN-γ alone did not induce NF-κB binding to either κBI or κBII elements.

We previously showed that ERK and JNK positively regulated, and p38mapk inhibited, IFN-γ-plus-ManLAM induction of iNOS-NO· (13). Since ERK can increase c-Fos expression and JNK can activate c-Jun, this would appear to suggest a role for AP-1, especially in light of the fact that there are three nonconsensus AP-1 binding sites present on the 5′-flanking region of the iNOS promoter. However, previous studies have shown that AP-1 is not involved in iNOS gene regulation with various stimuli (14, 45, 70). The inability of a dominant-negative c-Jun to affect iNOS induction would also not favor a role for AP-1 (14). Furthermore, the lack of supershifting of ManLAM-induced NF-κB with either a c-Fos or a c-Jun antibody would argue against a cooperative interaction between NF-κB and AP-1 components in this in vitro system, contrary to what has been previously described (63).

What then is the mechanism by which the MAPKs affect iNOS induction? Although MAPKs themselves are not generally considered to be components of the IKK-IκBα-NF-κB signaling pathway per se, they may directly or indirectly influence NF-κB activity (37, 48, 53, 62). However, using specific inhibitors of the individual MAPKs, we found that the MAPKs did not significantly affect ManLAM-induced NF-κB activation. Although NF-κB activation may be enhanced by direct phosphorylation of p50 or p65 subunits (41, 76), this unique mechanism has not been attributed to the MAPKs. Moreover, the effects of MAPKs on NF-κB activation are likely to be cell and/or stimulus specific (47). For example, p38mapk may either inhibit (4, 8, 10, 32), augment (11, 12), or have no effect on (27, 28) NF-κB activation.

Other novel and more complex MAPK-NF-κB interactions have been reported that could still account for a MAPK-NF-κB cooperation or antagonism. First, Carter and colleagues (11, 12) demonstrated that in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells, p38mapk augmented NF-κB-dependent gene expression by phosphorylating the TATA-binding protein (TBP), enhancing the binding of TBP to the TATA box (12). Conversely, ERK negatively regulated NF-κB-dependent gene expression by inhibiting TBP binding to the TATA box (11). The inverse roles we found with ERK and p38mapk in the context of NF-κB activation and iNOS-NO· expression (13) would argue against such a mechanism in our system. Second, Li and colleagues (42) showed that protein kinase C-epsilon (PKCɛ) activation of NF-κB was completely abolished when either ERK or JNK, both of which were activated by PKCɛ, was inhibited. Third, MAPKs may also influence one another; e.g., p38mapk may inhibit JNK or ERK activation (8, 14, 35), potentially further complicating the network of signaling pathways with NF-κB. Fourth, Alepuz and coworkers (3) recently showed a novel role for HOG1, a yeast equivalent of p38mapk. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, HOG1 itself was found to be intimately linked with promoter regions during stress responses, essentially behaving as part of a transcription activation complex (3). Although the general applicability of this phenomenon to mammalian MAPKs is not known, Meyer et al. (48) showed that JNK may directly interact with c-Rel to enhance NF-κB binding to its cis-regulatory element.

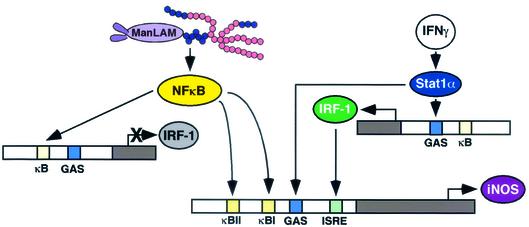

In summary, we demonstrated that ManLAM induction of iNOS and NO· in murine macrophages is dependent on the IKK-NF-κB signaling pathway (Fig. 9). We further showed that although ManLAM induced NF-κB binding to the IRF-1 promoter region, this was insufficient for IRF-1 expression, perhaps accounting for the inability of ManLAM alone to induce iNOS-NO· expression (Fig. 1A). The roles MAPKs play in influencing iNOS gene expression are complex and have yet to be fully elucidated. The biological significance of these signaling pathways in human TB remains unknown, although in the human iNOS gene, four NF-κB binding sites were shown to regulate transcription (29). Furthermore, since NF-κB has been shown to activate genes that may either enhance (e.g., iNOS) or attenuate (e.g., COX-2) microbial host defense, and NF-κB may be potentially activated by a variety of mycobacterial antigens, the role of NF-κB in toto in host defense in M. tuberculosis-infected human cells remains to be defined.

FIG. 9.

Cartoon diagram of the transcriptional regulation of iNOS by IFN-γ and ManLAM. The relative positions of the κBI, κBII, GAS, and ISRE sites in the drawing, as portrayed for simplicity's sake, do not accurately reflect their actual locations.

Acknowledgments

E.D.C. is supported by NIH-RO1-HL66112-01A1, the Parke-Davis Atorvastatin Research Award, and the American Lung Association Career Investigator Award.

We thank Patrick Brennan and John Belisle for the ManLAM; William Murphy, Charles Lowenstein, and Robert Scheinman for the various iNOS-luc constructs; Sonya Flores and Jerry Schaak for the adenovirus vector constructs; and James Degregori, Jerry Schaak, Sonya Flores, Adela Cota-Gomez, and David Riches for helpful discussions.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, L. B., M. C. Dinauer, D. E. Morgenstern, and J. L. Krahenbuhl. 1997. Comparison of the roles of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the host response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis using transgenic mice. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:237-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, L. B., Y. Fukutomi, and J. L. Krahenbuhl. 1993. Regulation of murine macrophage effector functions by lipoarabinomannan from mycobacterial strains with different degrees of virulence. Infect. Immun. 61:4173-4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alepuz, P. M., A. Jovanovic, V. Reiser, and G. Ammerer. 2001. Stress-induced MAP kinase Hog1 is part of transcription activation complexes. Mol. Cell 7:767-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpert, D., P. Schwenger, J. Han, and J. Vilcek. 1999. Cell stress and MKK6b-mediated p38 MAP kinase activation inhibit tumor necrosis factor-induced IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22176-22183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeuerle, P. A. 1998. Pro-inflammatory signaling: last pieces in the NF-κB puzzle? Curr. Biol. 8:R19-R22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin, A. S. 2001. The transcription factor NF-κB and human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 107:3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes, P. F., D. Chatterjee, J. S. Abrams, S. Lu, E. Wang, M. Yamamura, P. J. Brennan, and R. L. Modlin. 1992. Cytokine production induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. J. Immunol. 149:541-547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkenkamp, K. U., L. M. L. Tuyt, C. Lummen, A. T. J. Wierenga, W. Kruijer, and E. Vellenga. 2000. The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 enhances nuclear factor-κB transcriptional activity by a non-specific effect upon the ERK pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131:99-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwell, T. S., and J. W. Christman. 1997. The role of nuclear factor-κB in cytokine gene regulation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 17:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowie, A. G., and L. A. J. O'Neill. 2000. Vitamin C inhibits NF-κB activation by TNF via the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Immunol. 165:7180-7188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter, A. B., and G. W. Hunninghake. 2000. A constitutive active MEK→ERK pathway negatively regulates NF-κB-dependent gene expression by modulating TATA-binding protein phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:27858-27864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter, A. B., K. L. Knudtson, M. M. Monick, and G. W. Hunninghake. 1999. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for NF-κB-dependent gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30858-30863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan, E. D., K. R. Morris, J. T. Belisle, P. Hill, L. K. Remigio, P. J. Brennan, and D. W. H. Riches. 2001. Induction of iNOS-NO by lipoarabinomannan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by MEK1-ERK, MKK7-JNK, and NF-κB signaling pathways. Infect. Immun. 69:2001-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan, E. D., and D. W. H. Riches. 2001. IFNγ + LPS-induction of iNOS is modulated by ERK, JNK/SAPK, and p38mapk in a mouse macrophage cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280:C441-C450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan, E. D., B. W. Winston, S.-T. Uh, M. W. Wynes, D. M. Rose, and D. W. H. Riches. 1999. Evaluation of the role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by IFN-γ and TNFα in mouse macrophages. J. Immunol. 162:415-422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan, J., K. Tanaka, D. Carroll, J. Flynn, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on murine infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:736-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan, J., Y. Xing, R. S. Magliozzo, and B. R. Bloom. 1992. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 175:1111-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatterjee, D., and K.-H. Khoo. 1998. Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan: an extraordinary lipoheteroglycan with profound physiological effects. Glycobiology 8:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee, D., K. Lowell, B. Rivoire, M. R. McNeil, and P. J. Brennan. 1992. Lipoarabinomannan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 267:6234-6239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee, D., A. D. Roberts, K. Lowell, P. J. Brennan, and I. M. Orme. 1992. Structural basis of capacity of lipoarabinomannan to induce secretion of tumor necrosis factor. Infect. Immun. 60:1249-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper, A. M., J. P. Pearl, J. V. B. Brooks, S. Ehlers, and I. M. Orme. 2000. Expression of the nitric oxide synthase 2 gene is not essential for early control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the murine lung. Infect. Immun. 68:6879-6882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cota-Gomez, A., N. C. Flores, C. Cruz, A. Casullo, T. Y. Aw, H. Ichikawa, J. Schaack, R. Scheinman, and S. C. Flores. 2002. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat protein activates human umbilical vein endothelial cell E-selectin expression via an NF-κB-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14390-14399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullen, B. R., and M. H. Malim. 1992. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase as a eukaryotic reporter gene. Methods Enzymol. 216:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding, A. H., C. F. Nathan, and D. J. Stuehr. 1988. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J. Immunol. 141:2407-2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellner, J. J., and T. M. Daniel. 1979. Immunosuppression by mycobacterial arabinomannan. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 35:250-257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang, F. C. 1997. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-related antimicrobial activity. J. Clin. Investig. 100:S43-S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiebich, B. L., B. Mueksch, M. Boehringer, and M. Hull. 2000. Interleukin-1β induces cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 synthesis in human neuroblastoma cells: Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB. J. Neurochem. 75:2020-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiebich, B. L., S. Schleichers, R. D. Butcher, A. Craig, and K. Lieb. 2000. The neuropeptide substance P activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase resulting in IL-6 expression independently from NF-κB. J. Immunol. 165:5606-5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geller, D. A., C. J. Lowenstein, R. A. Shapiro, A. K. Nussler, M. DiSilvio, S. C. Wang, D. K. Nakayama, R. L. Simmons, S. H. Snyder, and T. R. Billiar. 1993. Molecular cloning and expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase from human hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3491-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giri, D. K., R. T. Mehta, R. G. Kansal, and B. B. Aggarwal. 1998. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex activates nuclear transcription factor-κB in different cell types through reactive oxygen intermediates. J. Immunol. 161:4834-4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green, S. J., R. M. Crawford, J. T. Hockmeyer, M. S. Meltzer, and C. A. Nacy. 1990. Leishmania major amastigotes initiate the l-arginine-dependent killing mechanism in IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages by induction of TNF-α. J. Immunol. 145:4290-4297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanov, V. N., and Z. Ronai. 2000. p38 protects human melanoma cells from UV-induced apoptosis through down-regulation of NF-κB activity and Fas expression. Oncogene 19:3003-3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jagannath, C., J. K. Actor, and R. L. J. Hunter. 1998. Induction of nitric oxide in human monocytes and monocyte cell lines by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nitric Oxide 2:174-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jobin, C., A. Panja, C. Hellerbrand, Y. Iimuro, J. Didonato, D. A. Brenner, and R. B. Sartor. 1998. Inhibition of proinflammatory molecule production by adenovirus-mediated expression of a nuclear factor κB super-repressor in human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 160:410-418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones, C. A., and J. K. Brown. 1999. p38 inhibition increases ERK1/ERK2 kinase activity and DNA synthesis in airway smooth muscle cells: evidence for cross-talk between mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159:A722. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamijo, R., H. Harada, T. Matsuyama, M. Bosland, J. Gerecitano, D. Shapiro, J. Le, S. I. Koh, T. Kimura, S. Green, T. W. Mak, T. Taniguchi, and J. Vilcek. 1994. Requirement for transcription factor IRF-1 in NO synthase induction in macrophages. Science 263:1612-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kan, H., Z. Xie, and M. S. Finkel. 1999. TNF-α enhances cardiac myocyte NO production through MAP kinase-mediated NF-κB activation. Am. J. Physiol. 277:H1641-H1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karin, M., and Y. Ben-Neriah. 2000. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:621-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karin, M., and A. Lin. 2002. NF-κB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 3:221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, H. C., J. H. Kim, J. W. Park, G. Y. Suh, M. P. Chung, O. J. Kwon, C. H. Rhee, and Y. C. Han. 1997. Difference of nitric oxide production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and airway epithelial cells between healthy volunteers and patients with tuberculosis. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 44(Suppl. 2):72-75. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kushner, D. B., and R. P. Ricciardi. 1999. Reduced phosphorylation of p50 is responsible for diminished NF-κB binding to the major histocompatibility complex class I enhancer in adenovirus type 12-transformed cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2169-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, R. C. X., P. Ping, J. Zhang, W. B. Wead, X. Cao, J. Gao, Y. Zheng, S. Huang, J. Han, and R. Bolli. 2000. PKCe modulates NF-κB and AP-1 via mitogen-activated protein kinases in adult rabbit cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 279:H1679-H1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liew, F. Y., Y. Li, and S. Millott. 1990. Tumor necrosis factor-α synergizes with IFN-γ in mediating killing of Leishmania major through the induction of nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 145:4306-4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, L., A. Paul, C. J. MacKenzie, C. Bryant, A. Graham, and R. Plevin. 2001. Nuclear factor κB is involved in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated induction of interferon regulatory factor-1 and GAS/GAF DNA-binding in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134:1629-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowenstein, C. J., E. W. Alley, P. Raval, A. D. Snowman, S. H. Snyder, S. W. Russell, and W. J. Murphy. 1993. Macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene: two upstream regions mediate induction by interferon γ and lipopolysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9730-9734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacMicking, J. D., R. J. North, R. LaCourse, J. S. Mudgett, S. K. Shah, and C. F. Nathan. 1997. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5243-5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Means, T. K., R. P. Pavlovich, D. Roca, M. W. Vermeulen, and M. J. Fenton. 2000. Activation of TNF-α transcription utilizes distinct MAP kinase pathways in different macrophage populations. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:885-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer, C. F., X. Wang, C. Chang, D. Templeton, and T. H. Tan. 1996. Interaction between c-Rel and the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 signaling cascade in mediating κB enhancer activation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:8971-8976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno, C., J. Taverne, A. Mehlert, C. A. W. Bate, R. J. Brealey, A. Meager, G. A. W. Rook, and J. H. L. Playfair. 1989. Lipoarabinomannan from Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces the production of tumour necrosis factor from human and murine macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 76:240-245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy, W. J., M. Muroi, X. Zhang, T. Suzuki, and S. W. Russell. 1996. Both a basal and an enhancer IB element is required for full induction of the mouse inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J. Endotoxin Res. 3:381-393. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicholson, S., M. da Gloria Bonecini-Almeida, J. R. Lapa e Silva, C. Nathan, Q.-W. Xie, R. Mumford, J. R. Widner, J. Calaycay, J. Geng, N. Boechat, C. Linhares, W. Rom, and J. L. Ho. 1996. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 183:2293-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nozaki, Y., Y. Hasegawa, S. Ichiyama, I. Nakashima, and K. Shimokata. 1997. Mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent killing of Mycobacterium bovis BCG in human alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65:3644-3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park, J.-H., and L. Levitt. 1993. Overexpression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1) enhances T-cell cytokine gene expression: role of AP1, NF-AT, and NF-κB. Blood 82:2470-2477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pine, R. 2002. IRF and tuberculosis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Platten, M., W. Wick, J. Wischhusen, and M. Weller. 2001. N-[3,4-Dimethoxycinnamoyl]-anthronilic acid (tranilast) suppresses microglial inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and activity induced by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Br. J. Pharmacol. 134:1279-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Read, M. A., J. E. Brownell, T. B. Gladysheva, M. Hottelet, L. A. Parent, M. B. Coggins, J. W. Pierce, V. N. Podust, R.-S. Luo, V. Chau, and V. J. Palombella. 2000. Nedd8 modification of Cul-1 activates SCF (β-TrCP)-dependent ubiquitination of IκBα. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2326-2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rich, E. A., M. Torres, E. Sada, C. K. Finegan, B. D. Hamilton, and Z. Toossi. 1997. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)-stimulated production of nitric oxide by human alveolar macrophages and relationship of nitric oxide production to growth inhibition of MTB. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rockett, K. A., R. Brookes, I. Udalova, V. Vidal, A. V. Hill, and D. Kwiatkowski. 1998. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces nitric oxide synthase and suppresses growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a human macrophage-like cell line. Infect. Immun. 66:5314-5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ropert, C., I. C. Almeida, M. Closel, L. R. Travassos, M. A. J. Ferguson, P. Cohen, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Requirement of mitogen-activated protein kinases and IκB phosphorylation for induction of proinflammatory cytokines synthesis by macrophages indicates functional similarity of receptors triggered by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from parasitic protozoa and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 166:3423-3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scanga, C. A., V. P. Mohan, K. Tanaka, D. Alland, J. L. Flynn, and J. Chan. 2001. The inducible nitric oxide synthase locus confers protection against aerogenic challenge of both clinical and laboratory strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 69:7711-7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlesinger, L. S., S. R. Hull, and T. M. Kaufman. 1994. Binding of the terminal mannosyl units of lipoarabinomannan from a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to human macrophages. J. Immunol. 152:4070-4079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schouten, G. J., A. C. O. Vertegaal, S. T. Whiteside, A. Israel, M. Toebes, J. C. Dorsman, A. J. van der Eb, and A. Zantema. 1997. IκBα is a target for the mitogen-activated 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase. EMBO J. 16:3133-3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein, B., A. S. Baldwin, D. W. Ballard, W. C. Greene, P. Angel, and P. Herrlich. 1993. Cross-coupling of the NF-κB p65 and Fos/Jun transcription factors produces potentiated biological function. EMBO J. 12:3879-3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strohmeier, G. R., and M. J. Fenton. 1999. Roles of lipoarabinomannan in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 1:709-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toossi, Z., B. D. Hamilton, M. H. Phillips, L. E. Averill, J. J. Ellner, and A. Salvekar. 1997. Regulation of nuclear factor-κB and its inhibitor IκB-α/MAD-3 in monocytes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and during human tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 159:4109-4116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wada, H., E. T. H. Yeh, and T. Kamitani. 2000. A dominant-negative UBC12 mutant sequesters NEDD8 and inhibits NEDD8 conjugation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17008-17015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, C.-H., C.-Y. Liu, H.-C. Lin, C.-T. Yu, K.-F. Chung, and H.-P. Kuo. 1998. Increased exhaled nitric oxide in active pulmonary tuberculosis due to inducible NO synthase upregulation in alveolar macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 11:809-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie, Q., R. Whisnant, and C. Nathan. 1993. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 177:1779-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xie, Q.-W., H. J. Cho, J. Calaycay, R. A. Mumford, K. M. Swiderek, T. D. Lee, A. Ding, T. Troso, and C. Nathan. 1992. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science 256:225-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamada, H., S. Mizuno, M. Reza-Gholizadeh, and I. Sugawara. 2001. Relative importance of NF-κB p50 in mycobacterial infection. Infect. Immun. 69:7100-7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang, X., Y. Chen, and D. Gabuzda. 1999. ERK MAP kinase links cytokine signals to activation of latent HIV-1 infection by stimulating a cooperative interaction of AP-1 and NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27981-27988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yeh, E. T. H., L. Gong, and T. Kamitani. 2000. Ubiquitin-like proteins: new wines in new bottles. Gene 248:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, Y., M. Broser, and W. N. Rom. 1994. Activation of the interleukin 6 gene by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or lipopolysaccharide is mediated by nuclear factors NF-IL6 and NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2225-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, Y., M. Doerfler, T. C. Lee, B. Guillemin, and W. N. Rom. 1993. Mechanisms of stimulation of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α by Mycobacterium tuberculosis components. J. Clin. Investig. 91:2076-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhong, H., R. E. Voll, and S. Ghosh. 1998. Phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol. Cell 1:661-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]