Abstract

In vivo intoxication with Bordetella pertussis toxin (PTX) elicits a variety of physiological responses including a marked leukocytosis, disruption of glucose regulation, adjuvant activity, alterations in vascular function, hypersensitivity to vasoactive agents, and death. We recently identified Bphs, the locus controlling PTX-induced hypersensitivity to the vasoactive amine histamine, as the histamine H1 receptor (Hrh1). In this study Bphs congenic mice and mice with a disrupted Hrh1 gene were used to examine the role of Bphs/Hrh1 in the genetic control of susceptibility to a number of phenotypes elicited following in vivo intoxication. We report that the contribution of Bphs/Hrh1 to the overall genetic control of responsiveness to PTX is restricted to susceptibility to histamine hypersensitivity and enhancement of antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity responses. Furthermore, the genetic contribution of Bphs/Hrh1 to vasoactive amine sensitization is specific for histamine, since hypersensitivity to serotonin was unaffected by Bphs/Hrh1. Bphs/Hrh1 also did not significantly influence susceptibility to the lethal effects, the leukocytosis response, disruption of glucose regulation, and histamine-independent increases in vascular permeability associated with in vivo intoxication. Nevertheless, significant interstrain differences in susceptibility to the lethal effects of PTX and leukocytosis response were observed. These results indicate that the phenotypic variation in responsiveness to PTX reflects the genetic control of distinct intermediate phenotypes rather than allelic variation in genes controlling overall susceptibility to intoxication.

Pertussis toxin (PTX) is a major virulence factor of Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough (9). The holotoxin is a hexameric protein that conforms to the A/B model of bacterial exotoxins (31). The A subunit is an ADP-ribosyltransferase which affects signal transduction by ribosylation of the α subunit of trimeric Gi proteins while the B oligomer binds cell surface receptors on a variety of mammalian cells (19, 31). PTX, when administered in vivo, elicits a large number of physiological responses including disruption of glucose regulation, leukocytosis, adjuvant activity, increased vascular permeability associated with alteration of blood-tissue barrier functions, sensitization to vasoactive agents, and death (12, 24, 27, 29, 44).

Inbred strains of mice differ in susceptibility to vasoactive amine challenge following PTX sensitization in that genetically susceptible strains die from hypotensive and hypovolemic shock whereas resistant strains do not (29, 43). Bphs, the gene controlling susceptibility to PTX-induced hypersensitivity to histamine, was previously mapped to the central region of mouse chromosome 6 (39) and recently identified as being the histamine H1 receptor (Hrh1) (25). As the first step in positionally cloning Bphs, we generated a panel of interval-specific recombinant congenic lines by using marker-assisted selection to introgress the susceptible SJL/J Bphs allele (Bphss) onto the resistant C3H/HeJ background. One particular line, C3H.SJL-BphssD, was studied in detail and found to be as susceptible to histamine sensitization as were SJL/J mice over a wide range of histamine doses. Since the relationship between the genetic control of susceptibility to vasoactive amine sensitization and the plethora of phenotypes associated with PTX intoxication is unclear, we utilized C3H.SJL-BphssD congenic mice and mice with a disrupted Hrh1 gene to examine the role of Bphs in the genetic control of a number of these phenotypes. Our results demonstrate that phenotypic variation in responsiveness to PTX reflects the genetic control of specific intermediate phenotypes rather than susceptibility and resistance to intoxication in general and that Bphs appears to be restricted to the genetic control of histamine sensitization and the adjuvant activity of PTX.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

SJL/J and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat, C3H/HeJ (C3H.SJL-BphshD), and C3H.SJL-BphssD (homozygous and heterozygous) congenic mice, generated by breeding heterozygous C3H.SJL-Bphss/hD mice (25), were produced in either the animal facilities at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, or at Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, Mass.). Animals were maintained in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

PTX in vivo intoxication.

Mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with purified PTX (List Biological Laboratories, Inc.) in 0.025 M Tris buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl and 0.017% Triton X-100, pH 7.6. Control animals received carrier.

Virulence testing.

Mice were injected i.v. with PTX on day 0, and mortality was recorded as a function of time postchallenge.

Blood analysis.

All laboratory blood tests were performed by the Diagnostic Laboratory of the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. Twenty-four-hour fasting blood glucose determinations and total leukocyte (WBC) counts were performed at 3 days post-PTX injection. Responsiveness to epinephrine was assessed by determining blood glucose levels 30 min after the intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 5.0 μg of epinephrine in 0.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Tissue vascular permeability determinations.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as the radiolabeled protein tracer to measure vascular permeability (23). BSA was radiolabeled with 125I by the chloramine T method. The specific activity of the labeled 125I-BSA was 2.0 μCi/mg. For tissue permeability measurements, mice were injected i.v. with 0.5 ml (1.0 μCi) of 125I-BSA in PBS at a concentration of approximately 2 mg/ml. Changes in tissue permeability were determined 3 days following i.v. injection of either carrier or PTX. After 1 h, the animals were killed, 100 μl of blood was collected, and the brains and samples of striated thigh muscle were collected. The tissues were thoroughly rinsed with PBS, blotted dry, and weighed, and the amount of 125I-BSA in each specimen and blood sample was determined. A permeability index was calculated by dividing the 125I-BSA counts per minute per gram of tissue by the 125I-BSA counts per minute per milliliter of blood.

Vasoactive amine sensitivity testing.

Histamine and serotonin hypersensitivities were determined by i.v. injection of histamine or serotonin (milligrams per kilogram of body weight [dry weight], free base) suspended in PBS. Deaths were recorded at 30 min and 12 h postchallenge. The results are expressed as the number of deaths over the number of animals studied.

Enhancement of antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH).

Mice were injected with 0.05 ml of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) consisting of equal volumes of CFA (200 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra) and ovalbumin (OVA) or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide 35-55 (MOG 35-55) in saline (1.0 mg/ml) in the left footpad and 0.025 ml of emulsion at the base of the tail and scruff of the neck. Immediately thereafter, each animal received PTX by i.v. injection. Seven days later the average thickness of the right pinna was determined by taking three measurements with a spring-loaded micrometer. Subsequently, each pinna was injected with 10 μl of physiological saline containing 1.0 mg of OVA or MOG 35-55/ml. Ear thickness measurements were taken at various times postchallenge, and the corrected average thickness was determined.

Statistical methods.

A two-way (5 × 2) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare WBC counts among the five strains and across two treatment conditions (carrier and PTX). Fasting blood glucose levels, with and without epinephrine treatment, were examined by a three-way (5 × 2 × 2) repeated-measure ANOVA given the five strains and two treatment conditions. The permeability index was examined by a three-way (3 × 2 × 2) repeated-measure ANOVA since correlated data were obtained from two different anatomic sites from three strains and two conditions. Ear thickness changes postchallenge were examined by repeated-measure ANOVA with orthogonal decomposition of the time effects.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PTX toxicity.

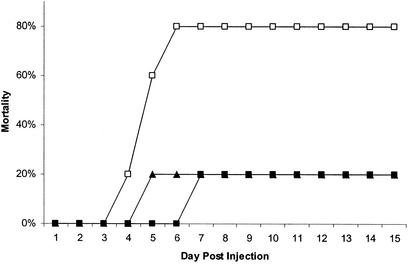

SJL/J mice exhibited greater sensitivity to the toxic effects of PTX than did C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice (Fig. 1). For SJL/J mice deaths were first observed at 4 days postinjection (20%), increasing to 80% by day 6 through day 15. Similarly, mortality was delayed in C3H/HeJ (20%) and C3H.SJL-BphssD (20%) mice until days 6 and 4, respectively. However, compared to SJL/J mice no increase in incidence was observed through day 15. These results establish that SJL/J mice are more sensitive to the toxic effects of PTX than are C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice and that Bphs/Hrh1 alleles do not play a role in controlling susceptibility to the toxic effects of PTX. The time to death and mortality following intoxication with PTX are similar to those reported previously at corresponding doses (26, 30).

FIG. 1.

Mortality of SJL/J (□), C3H/HeJ (▴), and C3H.SJL-BphssD (▪) mice injected i.v. with 2.5 μg of PTX (List Biological Laboratories, Inc.) in 0.025 M Tris buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl and 0.017% Triton X-100, pH 7.6. Five mice were injected per test group. Mice were monitored daily for viability, and the data are expressed as the cumulative percent mortality versus the day postinjection.

Susceptibility to the leukocytosis-promoting activity of PTX.

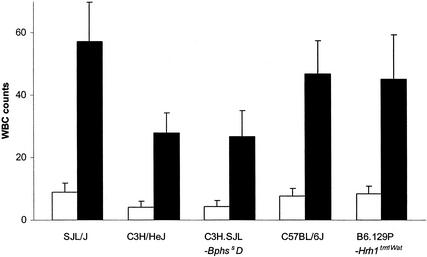

An analysis of the genetic control of the leukocytosis response elicited by PTX revealed that all strains exhibited a pronounced and significant leukocytosis 3 days following intoxication (Fig. 2). There were significant differences in the number of WBCs observed among the strains. SJL/J mice responded with an average WBC count of 57.0 × 10−3 cells/μl compared to 27.7 × 10−3 and 26.7 × 10−3 cells/μl for C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice, respectively. Similarly, C57BL/6J and B6.129-Hrh1tm1Wat mice exhibited an average WBC count 1.7-fold that of C3H/HeJ mice. However, there was no significant difference in the relative increase, which ranged from 5.4- to 6.9-fold among the strains, indicating that all strains responded equally. Thus, the phenotypic variation in the number of WBCs comprising the leukocytosis response reflects the strain-specific basal differences in WBC numbers among the different strains (http://aretha.jax.org/pub-cgi/phenome/mpdcgi?rtn=disp/measplot&studyid=62&fld=WBC).

FIG. 2.

Leukocytosis response in PTX-treated SJL/J, C3H/HeJ, C3H.SJL-BphssD, C57BL/6J, and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice. Mice were injected with carrier (open bars) or 200.0 ng of PTX (solid bars) on day 0. Three days later the animals were killed, blood was collected in EDTA, and total WBC counts were determined. Units are expressed as 10−3/μl of blood ± standard deviations. Due to the unequal variances observed for the WBC counts among the 10 groups, a natural logarithm transformation was used to stabilize the variances. The two-way ANOVA indicated that there were significant differences between mouse strains (P < 0.0001) and between PTX- and carrier-treated mice (P < 0.0001). Multiple comparisons indicated that the WBC count for the SJL/J strain was higher than those for C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice. Similarly, both C57BL/6J and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice also had higher counts than did C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice. All other paired comparisons were not significant.

Additionally, there was no difference in the WBC counts between the Bphss congenic lines or B6.129-Hrh1tm1Wat and wild-type C57BL/6J mice, indicating that Bphs/Hrh1 does not play a role in controlling susceptibility to the leukocytosis response elicited by PTX. These results are consistent with those observed for CBA/J mice, which also exhibit a marked leukocytosis despite being resistant to histamine sensitization (40).

Hypoglycemia and refractivity to epinephrine-induced hyperglycemia.

All strains studied were susceptible to PTX-induced hypoglycemia and were equally refractory to the effects of epinephrine (Table 1). No significant difference was observed between either C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD or C57BL/6J and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice, indicating that Bphs/Hrh1 does not play a role in controlling these two responses. Additionally, there was no difference among the strains with respect to epinephrine-induced hyperglycemia in carrier-treated control mice.

TABLE 1.

PTX-induced hypoglycemia and responsiveness to epinephrine in SJL/J, C3H/HeJ, and C3H.SJL-BphssD micea

| Mouse strain | Blood glucose concn (mg/dl)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastingb

|

Epinephrine

|

|||

| Carrier | PTX | PTX | Carrier | |

| SJL/J | 100.2 ± 20.0 | 67.2 ± 10.2 | 74.0 ± 10.6 | 196.2 ± 20.2 |

| C3H/HeJ | 102.0 ± 22.0 | 69.4 ± 11.5 | 76.4 ± 15.7 | 197.4 ± 13.3 |

| C3H.SJL-Bphss D | 99.4 ± 15.3 | 69.2 ± 11.9 | 72.8 ± 13.4 | 195.2 ± 17.5 |

| C57BL/6J | 101.8 ± 17.1 | 71.8 ± 8.3 | 77.6 ± 12.4 | 194.8 ± 10.2 |

| B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat | 102.0 ± 12.3 | 74.6 ± 10.7 | 78.0 ± 10.4 | 191.8 ± 17.3 |

Twenty-four-hour fasting blood glucose levels were determined in cohorts of five mice 3 days following the i.v. injection of 200.0 ng of PTX. Control animals received carrier. Subsequently, each mouse received 5.0 μg of epinephrine by i.p. injection, and the blood glucose level was determined 30 min later. Mean blood glucose values ± standard deviations are presented.

There was an overall significant difference between fasting and epinephrine conditioning (P < 0.0001) with the epinephrine conditioning being greater than fasting. There was also a significant interaction between treatment with PTX or carrier only and results seen during fasting and epinephrine conditioning (P < 0.0001). This is seen in the blunted effect under fasting and epinephrine conditioning with PTX treatment compared to the elevated changes seen under fasting and epinephrine conditioning with carrier treatment only. No significant differences were observed among strains for any of the parameters.

The induction of hypoglycemia in experimental animals following exposure to PTX or whole B. pertussis organisms is a well-documented phenomenon, as is the attenuation of epinephrine-induced hyperglycemia (12, 24, 27, 29, 44). However, the role of PTX-induced hypoglycemia in disease pathogenesis in humans is much less clear. Regan and Tolstoouhov reported that infants with pertussis exhibited hypoglycemia (32). Subsequent studies failed to detect changes in fasting blood glucose levels in children with proven pertussis (3, 11). Similarly, there are mixed reports in the literature with respect to the induction of hypoglycemia following vaccination (2, 7, 13, 14, 16). These results are consistent with the induction of hypoglycemia being an intermediate phenotype that is genetically controlled rather than a cross-species global response to pertussis. In this regard, the PTX-induced hypoglycemic response has been reported to be independent of vasoactive amine sensitization (6, 28).

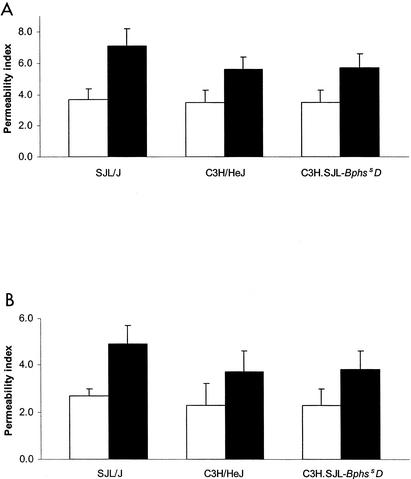

Vascular permeability changes elicited by PTX.

No significant differences were observed in the vascular permeability of SJL/J, C3H/HeJ, and C3H.SJL-Bphs2D carrier-treated mice (Fig. 3). In contrast, all three strains exhibited a significant increase in peripheral and central nervous system (CNS) vascular permeability following PTX treatment (Fig. 3). Interestingly, SJL/J mice exhibited a significantly greater increase in both peripheral (7.1 ± 1.1) and CNS (4.9 ± 0.8) vascular permeability than did C3H/HeJ (striated thigh muscle, 5.6 ± 0.8; brain, 3.7 ± 0.9) and C3H.SJL-BphssD (striated thigh muscle, 5.7 ± 0.9; brain, 3.8 ± 0.8) mice. These results are consistent with previous reports indicating that in vivo exposure to B. pertussis (1, 18) or intoxication with PTX leads to increased peripheral and CNS vascular permeability (21, 23, 30) and corroborate reports indicating that SJL/J mice are hyperresponsive in this regard (47, 48). Importantly, no difference in either peripheral or CNS vascular permeability was seen between C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice, indicating that Bphs/Hrh1 alleles do not control increased vascular permeability and that other genetic factors are presumably involved.

FIG. 3.

PTX-induced vascular permeability changes in striated thigh muscle (A) and brain (B) of SJL/J, C3H/HeJ, and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice. Mice were injected i.v. with either carrier (open bars) or 200.0 ng of PTX (solid bars) on day 0. Three days later 0.5 ml (1.0 μCi) of 125I-BSA in PBS at a concentration of approximately 2 mg/ml was administered by i.v. injection, and tissues were extracted 1 h later. Mean permeability indices ± standard deviations were determined by dividing the 125I-BSA counts per minute per gram of tissue by the 125I-BSA counts per minute per milliliter of blood (n = 5). There was an overall difference in permeability between striated smooth muscle and brain (P < 0.0001) with the muscle values being higher than the brain values. There were also differences between strains (P = 0.0013) and between PTX- and carrier-treated mice (P < 0.0001). Significant interaction with PTX or carrier treatment (P = 0.0394) was also seen among the strains. In particular, SJL/J mice showed the largest difference between PTX and carrier treatment while C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice showed smaller and comparable differences.

It has been suggested that the increased vascular permeability elicited by PTX is a direct function of hypersensitivity to histamine (4, 22). However, our results indicate that the two mechanisms may be independent of each other or that increased vascular permeability following sensitization with PTX is not solely mediated by signaling through H1R. In this regard, the vascular endothelium of SJL/J mice is significantly more sensitive to the effects of a variety of vasoactive agents including serotonin and bradykinin (20, 46) and that the vasoactive effects of serotonin could be blocked by 5-HT2 receptor antagonists. Interestingly, 5-HTR2A expression is increased following exposure of respiratory epithelial cells to PTX (5), suggesting that PTX may have a similar affect on endothelial cells.

PTX-induced hypersensitivity to histamine and serotonin.

Previously, it was demonstrated that sensitization to histamine following PTX treatment is controlled by Bphs/Hrh1 (25). Therefore, we directly assessed the role of Bphs/Hrh1 in controlling hypersensitivity to serotonin (Table 2). Clearly, SJL/J and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice are susceptible to histamine whereas C3H/HeJ mice are resistant. Similarly, SJL/J mice are susceptible to serotonin, but C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice are equally resistant to serotonin at both 30 and 720 min postchallenge. These results demonstrate that the genetic control of susceptibility to vasoactive amine sensitization is vasoactive amine specific and that Bphs/Hrh1 does not play a role in controlling sensitivity to serotonin.

TABLE 2.

PTX-induced sensitivity to histamine and serotonin in SJL/J, C3H/HeJ, and C3H.SJL-BphssD micea

| Mouse strain | Sensitization | No. dead/No. studied

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine

|

Serotonin

|

||||

| 30 min | 720 min | 30 min | 720 min | ||

| SJL/J | Carrier | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| PTX | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |

| C3H/HeJ | Carrier | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| PTX | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | |

| C3H.SJL-BphssD | Carrier | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| PTX | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | |

Mice were sensitized with 200.0 ng of PTX (List Biological Laboratories, Inc.) on day 0 by i.v. injection. Control animals received carrier. Three days later mice were challenged by i.v. injection with histamine or serotonin (25 mg/kg [dry weight] free base) in PBS. Results are expressed as the number of animals dead at 30 and 720 min postinjection over the number of animals studied.

These data help to explain some of the conflicting results in the literature with respect to differences in susceptibility to vasoactive amine sensitization elicited with histamine, serotonin, or combinations thereof among inbred strains of mice (22, 28, 29, 42, 43). Other factors that we have clearly established as confounding in our studies over the years include the purity of the PTX and the variability in classifying strains as susceptible and resistant based on vastly varying times to death as the end point. Additionally, sensitization of mice by i.p. injection with crude preparations of PTX and i.p. challenge with the vasoactive agent lead to increased variability among inbred strains, whereas i.v. sensitization with purified PTX and i.v. challenge result in a consistently uniform outcome with the only variable among inbred strains being the 50% lethal dose. C3H/HeJ and CBA/J mice are the only two inbred strains that we have identified that are completely resistant to histamine sensitization at all doses tested, including a high dose of 100 mg/kg (25).

Our data are also consistent with susceptibility to vasoactive amine sensitization being a two-step process: an induction phase characterized by a 2- to 3-day latency period following intoxication and a rapid effector phase typified by a time to death due to hypotensive and hypovolemic shock of minutes to hours after challenge with the vasoactive agent (28, 29). Additionally, vasoactive amine sensitization is characterized by a period of hypersensitivity that lasts upward of 60 days (29, 30). This suggests that the induction phase is associated with the synthesis and storage of additional vasoactive factors within endothelial cells that are released upon exposure to vasoactive agents such as histamine or increased, protracted expression of H1R by cells. In this regard, it is known that inflammatory stimuli induce the synthesis and storage of interleukin-8, von Willebrand factor, P-selectin, endothelin, and CD63 in Weibel-Palade bodies within endothelial cells (41, 45) and that histamine and serotonin are secretagogues for the release of these agents (15, 34). Thus, in this model death due to hypotensive and hypovolemic shock following PTX sensitization and exposure to histamine is due to the combined direct vasodilatory effects of histamine and the actions of released stored products from Weibel-Palade bodies which together result in an insurmountable affront to the vascular endothelium. Without exposure to PTX the endothelial cells can compensate for the effects of histamine, since the animals do not die, but they cannot compensate for the amplified signaling through multiple receptors and synergistic second-messenger stimulation.

Transcriptional profiling following intoxication with catalytically active PTX and recombinant mutant ADP-ribosyltransferase inactive PTX has led to the identification of genes that are both unregulated and down regulated (5, 8). The early transcriptional response is dominated by the increased expression of a large number of cytokine and chemokine genes, DNA-binding proteins, and NF-κB-regulated genes. Additionally, it was shown that 5-HTR2A and 5-HTR1E exhibit transcriptional changes following intoxication with PTX. Thus, genetic differences in susceptibility to serotonin sensitization may be a function of differential levels of 5-HTR subtype expression. In this regard, SJL/J and AKR/J mice are the prototype serotonin-susceptible strains, and susceptibility can be blocked with 5-HTR2 receptor selective antagonists (unpublished data).

Enhancement of antigen-specific DTH.

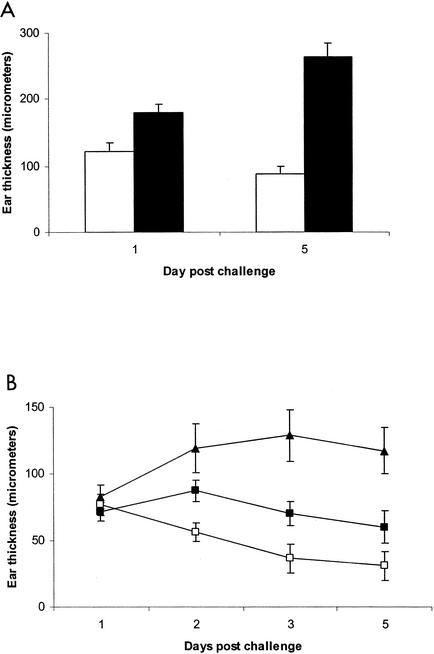

One of the principal immunomodulatory activities of PTX is its adjuvant activity. When PTX is used as an ancillary adjuvant at the time of immunization, it leads to enhanced and prolonged antigen-specific DTH responses (35). The DTH response elicited following immunization with PTX is mediated by CD4+ Th1 helper T cells that produce excessive amounts of the proinflammatory cytokine gamma interferon (36, 37). It was suggested that this is due to the direct effects of PTX on the responding T cells during sensitization such that they exhibit augmented production of gamma interferon at the time of challenge. Recent data, however, suggest that this may not be the case and that enhanced DTH responsiveness may be due to increased clonal expansion of Th1 helper T cells (38) driven by PTX activation of antigen-presenting cells (17, 33). C3H.SJL-BphssD mice immunized with OVA emulsified in CFA and given PTX at the time of immunization exhibited significantly greater DTH responses at day 1 and day 5 post-antigen challenge than did C3H/HeJ mice (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Bphs/Hrh1 controls enhancement of DTH responses elicited by PTX to both foreign antigen (A) and self antigen MOG 35-55 (B). C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD mice were sensitized with OVA while C57BL/6J and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice were injected with MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA. Immediately thereafter, each animal received PTX or carrier by i.v. injection. Seven days later the average thickness of the right pinna was determined by taking three measurements with a spring-loaded micrometer. Subsequently, each pinna was injected with 10 μl of physiological saline containing 1.0 mg of OVA or MOG 35-55/ml. Ear thickness measurements were taken at various times postchallenge, and the corrected average thickness was determined. Data are plotted as micrometers ± standard deviations. (A) Open bars, C3H/HeJ; solid bars, C3H.SJL-BphssD. The repeated-measure ANOVA for the DTH response to OVA revealed a statistically significant interaction (P < 0.0001) between the strain and the day postchallenge. In particular, C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD groups showed significantly different postchallenge changes in thickness (P < 0.0001). (B) ▴, C57BL/6J mice immunized with MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA plus PTX; ▪, B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice immunized with MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA plus PTX; □, C57BL/6J mice immunized with MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA without PTX. The repeated-measure ANOVA for the DTH response to MOG 35-55 indicated that the three groups had significantly different responses over the 5 days postchallenge as reflected in an overall significant group by time interaction (P < 0.0001). Orthogonal decompositions of the time effects indicated that the linear effect (P < 0.0001) and quadratic effect (P = 0.0003) differed among the three groups with the C57BL/6J mice immunized with MOG 35-55 emulsified in CFA plus PTX showing a positive increase with a leveling out after day 1 while C57BL/6J mice immunized without PTX and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice treated with PTX had decreasing values over time.

C57BL/6J mice immunized with MOG 35-55 given PTX at the time of immunization exhibited a significantly enhanced and protracted DTH response compared to that of C57BL/6J mice not receiving PTX (Fig. 4B). Similarly, wild-type C57BL/6J mice exhibited a significantly greater DTH response to MOG 35-55 than did B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice when immunized with PTX. Taken together, these results clearly indicate that signaling through Bphs/Hrh1 plays a role in eliciting CD4+ Th1 helper T cells when PTX is used as an adjuvant at the time of immunization. These results are consistent with the earlier report indicating that Bphs/Hrh1 is required for optimally eliciting encephalitogenic MOG 33-55-specific CD4+ Th1 T cells mediating experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (25). In B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice the onset of disease was delayed and the severity of clinical symptoms was reduced during the acute phase of the disease compared to C57BL/6J wild-type mice. The protection from experimental allergic encephalomyelitis was associated with immune deviation of the MOG 33-55 CD4+ T-cell response.

Summary.

Overall, the results of this study indicate that Bphs/Hrh1 does not play a significant role in the genetic control of susceptibility to toxicity, serotonin sensitization, or histamine-independent increased vascular permeability following in vivo intoxication. Similarly, there was no significant difference in responsiveness to PTX as assessed by the induction of hypoglycemia or refractivity to hyperglycemia following exposure to epinephrine or in the leukocytosis response between C3H/HeJ and C3H.SJL-BphssD or C57BL/6J and B6.129P-Hrh1tm1Wat mice following intoxication. Differences in the total WBC counts observed among the strains studied reflected differences in the basal WBC counts among the inbred strains. In contrast, Bphs/Hrh1 clearly controls susceptibility to PTX-induced hypersensitivity to histamine and enhancement of antigen-specific DTH responses mediated by CD4+ Th1 helper T cells.

Our results indicate that phenotypic variation in responsiveness to PTX reflects the genetic control of intermediate phenotypes rather than a generalized refractivity to PTX intoxication. This interpretation is consistent with two observations. First, unlike receptors for many bacterial toxins, a single molecular entity functioning as a receptor for PTX has not been identified. Rather, PTX appears to bind to common carbohydrate motifs shared by various glycoproteins and glycolipids, thereby enabling the intoxication of virtually all cells, albeit at different rates (10, 19). The second observation is that transcriptional profiling studies revealed a remarkably consistent, highly stereotyped response by peripheral blood mononuclear cells following exposure to B. pertussis and PTX rather than highly individualized responses (8, 17). Thus, studies designed to delineate the mechanisms and genetics underlying the pathological complications associated with B. pertussis infection and adverse reactions observed following vaccination require assessment of each of the intermediate phenotypes elicited by in vivo intoxication rather than global approaches designed to assess responsiveness to B. pertussis or PTX in general.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS36526, AI4515, and AI41747 and National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant RG-3129.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiel, S. A. 1976. The effects of Bordetella pertussis vaccine on cerebral vascular permeability. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 57:653-662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, I. M., and D. Morris. 1950. Encephalopathy after combined diphtheria-pertussis inoculation. Lancet i:537. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badr el Din, M. K., G. H. Aref, H. Mazloum, Y. A. el-Towsey, A. S. Kassem, M. A. Abdel-Moneim, and A. A. Abbassy. 1976. The beta-adrenergic receptors in pertussis. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79:213-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebo, B. F., T. Yong, E. L. Orr, and D. S. Linthicum. 1996. Hypothesis: a possible role for mast cells and their inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. Res. 45:340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belcher, C. E., J. Drenkow, B. Kehoe, T. R. Gingeras, N. McNamara, H. Lemjabbar, C. Basbaum, and D. A. Relman. 2000. The transcriptional response of respiratory epithelial cells to Bordetella pertussis reveals host defensive and pathogen counter-defensive strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13847-13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman, R. K., and J. J. Munoz. 1969. Hypoglycemia and its relationship to histamine sensitization in mice. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 131:42-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg, D. A., K. Lewis, C. M. Mink, P. D. Christenson, P. Chatfield, and J. D. Cherry. 1993. Severe reactions associated with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine: detailed study of children with seizures, hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes, high fevers, and persistent crying. Pediatrics 91:1158-1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldrick, J. C., A. A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, S. Duobit, C. L. Liu, C. E. Belcher, D. Botstein, L. M. Staudt, P. O. Brown, and D. A. Relman. 2002. Stereotyped and specific gene expression programs in human innate immune responses to bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:972-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bordet, J., and O. Gengou. 1906. Le microbe de la coqueluche. Ann. Inst. Pasteur 20:731-741. [Google Scholar]

- 10.el Baya, A., K. Bruckener, and M. A. Schmict. 1999. Nonrestricted differential intoxication of cells by pertussis toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:433-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furman, B. L., E. Walker, F. M. Sidey, and A. C. Wardlaw. 1988. Slight hyperinsulinemia but no hypoglycemia in pertussis patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 25:183-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furman, B. L., F. M. Sidey, and M. Smith. 1988. Metabolic disturbances produced by pertussis toxin, p. 147-172. In A. C. Wardlaw and R. Parton (ed.), Pathogenesis and immunity in pertussis. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 13.Globus, J. H., and J. L. Kohn. 1949. Encephalopathy following pertussis vaccine prophylaxis. JAMA 141:507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannik, C. A., and H. Cohen. 1979. Changes in plasma insulin concentration and temperature of infants after pertussis vaccination, p. 297-299. In C. R. Manclark and J. C. Hill (ed.), International symposium on pertussis. U.S. DHEW publication no. (NIH)79-1830. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Hattori, R., K. K. Hamilton, R. D. Fugates, R. P. McEver, and P. J. Sims. 1989. Stimulated secretion of endothelial von Willebrand factor is accompanied by rapid redistribution of the cell surface of the intracellular granule membrane protein GMP-140. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7768-7771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennessen, W., and U. Quast. 1979. Adverse reactions after pertussis vaccination. Dev. Biol. Stand. 43:95-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofstetter, H. H., C. L. Shive, and T. G. Forsthuber. 2002. Pertussis toxin modulates the immune response to neuroantigens injected in incomplete Freund's adjuvant: induction of Th1 cells and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the presence of high frequencies of Th2 cells. J. Immunol. 169:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt, L. B., V. Spasojevic, J. M. Dolby, and A. T. B. Standfast. 1961. Immunity in mice to an intracerebral challenge of Bordetella pertussis. J. Hyg. 59:373-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaslow, H. R., and D. L. Burns. 1992. Pertussis toxin and target eukaryotic cells: binding, entry, and activation. FASEB J. 6:2684-2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khare, S., K. Gokulan, and D. S. Linthicum. 2000. Vasoactive amine responses in murine cerebrovascular endothelial cells as measured by extracellular acidification rates. J. Neurosci. Res. 60:356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linthicum, D. S. 1982. Development of acute autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice: factors regulating the effector phase of the disease. Immunobiology 162:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linthicum, D. S., and J. A. Frelinger. 1982. Acute autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. II. Susceptibility is controlled by the combination of H-2 and histamine sensitization genes. J. Exp. Med. 156:31-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linthicum, D. S., J. J. Munoz, and A. Blaskett. 1982. Acute experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. I. Adjuvant action of Bordetella pertussis is due to vasoactive amine sensitization and increased vascular permeability of the central nervous system. Cell. Immunol. 73:299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locht, C. 1999. Molecular aspects of Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis. Int. Microbiol. 3:137-144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, R. Z., J. Gao, N. D. Meeker, P. D. Fillmore, K. S. K. Tung, T. Watanabe, J. F. Zachary, H. Offner, E. P. Blankenhorn, and C. Teuscher. 2002. Identification of Bphs, an autoimmune disease locus, as histamine receptor H1. Science 297:620-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morse, S. I., and J. H. Morse. 1976. Isolation and properties of the leukocytosis- and lymphocytosis-promoting factor of Bordetella pertussis. J. Exp. Med. 143:1483-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munoz, J. J. 1985. Biological activities of pertussigen (pertussis toxin), p. 1-18. In R. D. Sekura, J. Moss, and M. Vaughan (ed.), Pertussis toxin. Academic Press, Orlando, Fla.

- 28.Munoz, J. J., and R. K. Bergman. 1968. Histamine-sensitizing factors from microbial agents, with special reference to Bordetella pertussis. Bacteriol. Rev. 32:103-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz, J. J., and R. K. Bergman. 1977. Bordetella pertussis: immunological and other biological activities. Immunol. Ser. 4:1-235. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz, J. J., H. Arai, R. K. Bergman, and P. L. Sadowski. 1981. Biological activities of crystalline pertussigen from Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 33:820-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rappuoli, R., and M. Pizza. 1991. Structure and evolutionary aspects of ADP-ribosylating toxins, p. 1-20. In J. Abuf and J. Freer (ed.), Source book of bacterial protein toxins. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 32.Regan, J. C., and A. Tolstoouhov. 1936. Relations of acid base equilibrium to the pathogenesis and treatment of whooping cough. N. Y. State J. Med. 36:1075-1087. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan, M., L. McCarthy, R. Rappuoli, B. P. Mahon, and K. H. Mills. 1998. Pertussis toxin potentiates Th1 and Th2 responses to co-injected antigen: adjuvant action is associated with enhanced regulatory cytokine production and expression of the co-stimulatory molecules B7-1, B7-2 and CD28. Int. Immunol. 10:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schluter, T., and R. Bohnensack. 1999. Serotonin-induced secretion of von Willebrand factor from human umbilical vein endothelial cells via the cyclic AMP-signaling systems independent of increased cytoplasmic calcium concentration. Biochem. Pharmacol. 57:1191-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sewell, W. A., J. J. Munoz, and M. A. Vadas. 1983. Enhancement of the intensity, persistence, and passive transfer of delayed-type hypersensitivity lesions by pertussigen in mice. J. Exp. Med. 157:2087-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sewell, W. A., J. J. Munoz, R. Scollary, and M. A. Vadas. 1984. Studies on the mechanism of the enhancement of delayed-type hypersensitivity by pertussigen. J. Immunol. 133:1716-1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sewell, W. A., P. A. de Moerloose, J. L. McKimm-Breschkin, and M. A. Vadas. 1986. Pertussigen enhances antigen-driven interferon-γ production by sensitized lymphoid cells. Cell. Immunol. 97:238-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shive, C. L., H. Hofstetter, L. Arredondo, C. Shaw, and T. G. Forsthuber. 2000. The enhanced antigen-specific production of cytokines induced by pertussis toxin is due to clonal expansion of T cells and not to altered effector function of long-term memory cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2422-2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudweeks, J. D., J. A. Todd, E. P. Blankenhorn, B. B. Wardell, S. R. Woodward, N. D. Meeker, S. S. Estes, and C. Teuscher. 1993. Locus controlling Bordetella pertussis-induced histamine sensitization (Bphs), an autoimmune disease-susceptibility gene, maps distal to T-cell receptor β-chain gene on mouse chromosome 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:3700-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taub, R. N., W. Rosett, A. Adler, and S. I. Morse. 1972. Distribution of labeled lymph cells in mice during the lymphocytosis induced by Bordetella pertussis. J. Exp. Med. 136:1581-1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Utgaard, J. O., F. L. Jahnsen, A. Bakka, P Brandtzaeg, and G. Haraldsen. 1998. Rapid secretion of prestored interleukin 8 from Weibel-Palade bodies of microvascular endothelial cells. J. Exp. Med. 188:1751-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vas, N. M., C. M. de Souza, L. C. S. Maia, and D. G. Hanson. 1977. Effects of Bordetella pertussis on the sensitivity of inbred mice to vasoactive amines. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 53:560-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wardlaw, A. C. 1970. Inheritance and responsiveness to pertussis HSF in mice. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 38:573-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wardlaw, A. C., and R. Parton. 1983. Bordetella pertussis toxin. Pharmacol. Ther. 19:1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolff, B., A. R. Burns, J. Middleton, and A. Rot. 1998. Endothelial cell “memory” of inflammatory stimulation: human venular endothelial cells store interleukin 8 in Weibel-Palade bodies. J. Exp. Med. 188:1757-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yong, T., and D. S. Linthicum. 1996. Microvascular leakage in mouse pial venules induced by bradykinin. Brain Inj. 10:385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yong, T., B. F. Bebo, B. V. Sapatino, C. J. Welsh, E. L. Orr, and D. S. Linthicum. 1994. Histamine-induced microvascular leakage in pial venules: differences between the SJL/J and BALB/c inbred strains of mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 11:161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yong, T., G. A. Meininger, and D. S. Linthicum. 1993. Enhancement of histamine-induced vascular leakage by pertussis toxin in SJL/J mice but not BALB/c mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 45:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]