Abstract

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which enzymatically depletes tryptophan, is an important antimicrobial defense mechanism against susceptible pathogens. In human epithelial cells, interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-induced IDO expression is transcriptionally enhanced by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). The purpose of this study was to identify those regulatory mechanisms responsible for this synergistic transcriptional activation of IDO. Nuclear concentrations of signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (Stat1) and IFN regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), transcription factors that bind gamma-activated sequences (GAS) and IFN-stimulated response elements (ISRE), respectively, were found to increase after stimulation with IFN-γ and TNF-α relative to stimulation with individual cytokines. Additionally, CCAAT enhancer binding protein-β (C/EBP-β) bound to one of three consensus C/EBP-β sites in the IDO regulatory region in response to TNF-α alone or combined with IFN-γ. A transcriptional reporter containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the IDO regulatory region was used to analyze the contribution of these enhancer elements to synergistic IDO gene expression in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α. Transcriptional activity following mutation of individual enhancers or large deletions within the regulatory region indicates that increased binding of IFN-γ-transactivated factors to GAS and ISRE sites alone is responsible for synergistic transcriptional activation of the IDO gene.

INTRODUCTION

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), secreted from activated Th1 cells and natural killer (NK) cells, stimulates production of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). (1,2) IDO activity represents the rate-limiting step in tryptophan catabolism along the kynurenine pathway and is an important antimicrobial defense mechanism.(3) IDO activity protects host cells from tryptophan auxotrophic pathogens by depleting pools of tryptophan required for their protein synthesis.(4) Among the pathogens susceptible to this mechanism in vitro are Chlamydia spp. and Toxoplasma.(1,4–7)

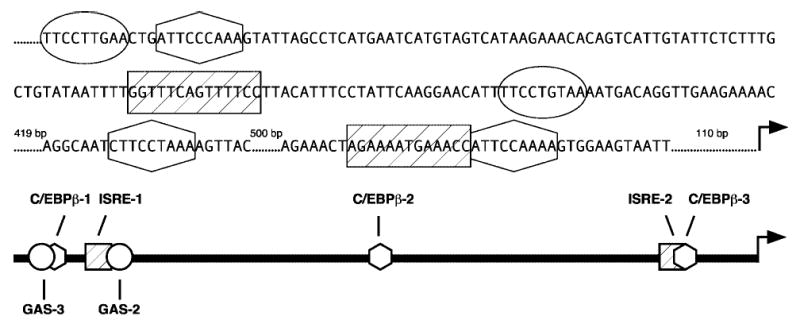

Although IDO is strictly an IFN-γ-induced gene product, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) can synergistically increase the transcriptional activation of the IDO gene in response to IFN-γ.(8,9) This is important biologically, as both cytokines are likely to be part of the inflammatory response associated with chlamydial infection.(10–12) Furthermore, the convergence of two distinct signaling pathways provides a model of gene expression for analyzing the cooperation of multiple transcription factors. IFN-γ signaling that leads to IDO induction begins with phosphorylation of the latent activator signal transducer and activator of transcription1α (Stat1α), which is phosphorylated at the IFN-γ-receptor (IFNGR) following binding of ligand. Stat1 then dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds gamma-activated sequences (GAS) to activate gene expression.(13–16) Two GAS sites (GAS-2 and GAS-3) exist upstream of the IDO coding region (Fig. 1); both are involved in activating gene expression.(17–19) Another GAS site is found within the regulatory region of the IFN regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) gene, the product of which is synthesized de novo following activation by IFN-γ.(20,21) IRF-1 binds upstream of the IDO gene at two IFN-γ-stimulated response elements (ISRE-1 and ISRE-2) (Fig. 1); each is involved in activating IDO gene expression.(17,18,22,23) Thus, Stat1 contributes directly to IDO induction by binding to GAS elements in the IDO regulatory region and indirectly by inducing production of IRF-1, which binds to ISRE elements in the IDO regulatory region.

FIG. 1.

The IDO regulatory region. Nucleotide sequence representing 1249 bases upstream of the start of transcription is shown. A scaled diagram of the 1300 nt upstream of the transcriptional start site is also presented. Activator binding regions below are represented by symbols that correspond to the enclosed nucleotide sequences above.

Previous data have shown synergistic transcriptional activation of IDO in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α to result from an increase in IFN-γ-induced signal transduction in comparison to that exhibited in response to IFN-γ alone.(19) Furthermore, the increase in signaling correlates with increased IFNGR expression at the cell surface.(19) This does not exclude the possibility, however, that additional transcription factors activated by TNF-α contribute directly to IDO transcriptional activation. The focus of this study is to determine if increases in IFN-γ-mediated signaling alone are responsible for the transcriptional synergy or if TNF-α-specific factors interact with IDO regulatory elements to form a more active transcriptional complex. One candidate for fulfilling this model is CCAAT enhancer binding protein-β (C/EBP-β), an activator latently expressed in the cytoplasm that translocates to the nucleus in response to TNF-α in a number of cell and tissue types.(24) Three potential C/EBP-β consensus binding elements exist upstream of the IDO coding region (Fig. 1), each of which may contribute to enhancement of transcriptional activation by TNF-α. Using an IDO transcriptional reporter system, we characterized the contribution of each of the ISRE, GAS, and C/EBP-β sites. This analysis revealed that the increase in IFN-γ-mediated signaling is directly responsible for the synergistic transcriptional activation and is independent of TNF-α-specific activator recruitment to the IDO regulatory region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytokines and antibodies

Recombinant IFN-γ (specific activity 1.6 × 107 U/mg protein) was obtained from Biogen (Cambridge, MA). Recombinant human TNF-α was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Antimouse and antirabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (sc-2047 and sc-2034) and polyclonal rabbit antihuman C/EBP-β antibodies (sc-150) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal Y12 antibody, directed against a family of constitutively expressed human splicing factors, was a generous gift of Dr. Eileen Bridge (Miami University).

Primers

Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). The oligonucleotide sequences used for amplification of IDO and β-actin cDNA are: IDO cDNA forward primer, 5′-CCTGACTTATGAGAACATGGAGCT-3′; IDO cDNA reverse primer, 5′-ATACACCAGACCGTCTGATAGCTG-3′; β-actin forward primer, 5′-GCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAG-3′; β-actin reverse primer, 5′-ATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC-3′.

Cell culture

The HeLa human epithelial cell line, obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD), was maintained in complete medium: Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM), (CellGro, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 10 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate (Sigma) at 37°C in 5% CO2.

RT-PCR

Cells were untreated or exposed to IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), TNF-α (5 ng/ml), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α at the respective concentrations in culture medium for 24 h. Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRI REAGENT (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (1 μg) was used for first-strand synthesis in a 20-μl reaction containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dNTPs (Takara Biomedicals, Otsu, Shiga, Japan), 10 mM DTT, RNasin (20 U), 25 μM random hexanucleotides, and SuperScript II (200 U) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After incubation at 42°C for 50 min, the reaction was terminated by heating at 70°C for 15 min.

cDNA (3 μl) was amplified in a 50-μl PCR reaction containing 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 9.0, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 1 μl α32P-ATP (10 mCi/ml, specific activity 800 Ci/mmol) (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA), and 0.2 μM forward and reverse primers of IDO or β-actin. PCR amplification was performed in a Perkin-Elmer thermal cycler (Norwalk, CT) according to the following protocol: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min for 26 cycles, followed by a final 5 min extension at 72°C. PCR products (20 μl) were separated electrophoretically on 8% polyacrylamide. Images were detected by scanning with a Storm 860 phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics/Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Preparation of nuclear extracts

HeLa cells were untreated or exposed to IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), TNF-α (5 ng/ml), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α in complete medium for 4 h. Cells were harvested, and extracts were prepared as described previously,(25) with the following modifications. Cells were gently lysed by homogenization in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin), and pelleted nuclei were slowly extracted with a high salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 25% [v/v] glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 M EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5 mM DTT). Nuclear extracts were dialyzed in 200 volumes of high salt buffer overnight, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C until used in immunoblot or binding assays. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL).

Immunoblot analysis

Nuclear extracts were mixed in an equal volume of sample buffer (125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 5% [w/v] SDS, 100 mM DTT, 25% [v/v] glycerol, and 0.1% [w/v] bromophenol blue), separated on denaturing 12% polyacrylamide, and transferred to nitrocellulose for probing. Y12 antibody was used in addition to antibodies specific for transcriptional activators to normalize nuclear protein. ECF substrate (Amersham Biosciences) was applied for protein visualization, and images were detected by phosphorimaging.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Synthetic 20-mer probes were created by annealing and end-labeling with α32P-CTP (10 mCi/ml, specific activity 3000 Ci/mmol) (Perkin-Elmer) using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (5 U) (Takara) in a 25-μl reaction mixture (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM DTT, 1 mM each of dATP, dGTP, and dTTP). Radiolabeled products were purified on a G25 Sephadex column (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). Normalized extract volumes were incubated 20 min at ambient temperature with radiolabed probes (1 pmol), binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM EDTA, and 50% [v/v] glycerol), 1 or 6 μg poly dI-dC (Amersham Biosciences), and 0.5 μg yeast tRNA (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA). Reactions were separated on 4% or 5.5% polyacrylamide, low-ionic strength gels at 15 V/cm for 6 h at 4°C. Images were detected by phosphorimaging.

Generation of reporter vectors

The regulatory region upstream of the human IDO gene within the GASinsIDOp/EGFP-C1 reporter vector(19) was amplified by PCR according to standard protocols with primers designed to insert base substitutions (Table 1) or delete stretches of sequence. The PCR products were ligated into the AseI and NheI sites of the EGFP-C1 vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as described.(19) The presence of substituted bases or deletions was confirmed by sequencing on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a reaction containing 500 ng plasmid template, 5 pmol primer, DYEnamic ET terminators (Amersham Biosciences), and H2O to a final volume of 7 μl.

Table 1.

Mutations in IDO Regulatory Region Enhancers

| Site | Consensus sequencea | IDO regulatory region sequenceb | Mutated sequencec |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAS-2 | ttncnnnaa | ttcctgtaa | atagtgtaa |

| GAS-3 | ttncnnnaa | ttccttgaa | atagttgaa |

| ISRE-1 | agtttcnntttncc/t | ggtttcagttttcc | ggtgtcagtgttcc |

| ISRE-2 | agtttcnntttncc/t | ggtttcattttcc | ggtgtcatgttct |

| C/EBP-β-1 | tg/tnngnaag/t | tttgggaat | tctgagcat |

| C/EBP-β-2 | tg/tnngnaag/t | tttaggaag | tctaagcag |

| C/EBP-β-3 | tg/tnngnaag/t | ttttggaat | tcttagcat |

The consensus sequences for GAS, ISRE, and C/EBP-β sites.

The respective enhancer sequence present within the IDO regulatory region.

Point mutations inserted in reporter constructs and EMSA probes.

Transfection and assessment of promoter activity in transfectants

The reporter constructs were purified using a maxicolumn (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, CA) and transfected into HeLa cells using an Effectene transfection kit (Qiagen). HeLa cells (8 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 24-well plates and cotransfected with 30 fmol GASinsIDOp/EGFP-C1 (WT) or appropriate mutant construct (MUT) and 30 fmol DsRed-C1 (Clontech) to monitor transfection efficiency. Culture medium was replaced with medium alone or medium supplemented with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml), TNF-α (5 ng/ml), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α 18–24 h after transfection. Following an additional 48-h incubation, the cells were harvested with EDTA/trypsin (200 μl), pelleted, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (250 μl) for analysis using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Cells expressing both red and green fluorescent proteins (GFP) were selected, and CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson) was used to calculate the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each replicate culture. Three independent MUT and WT comparisons were performed in triplicate. From these experiments, the data were pooled, and a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences in GFP expression.

RESULTS

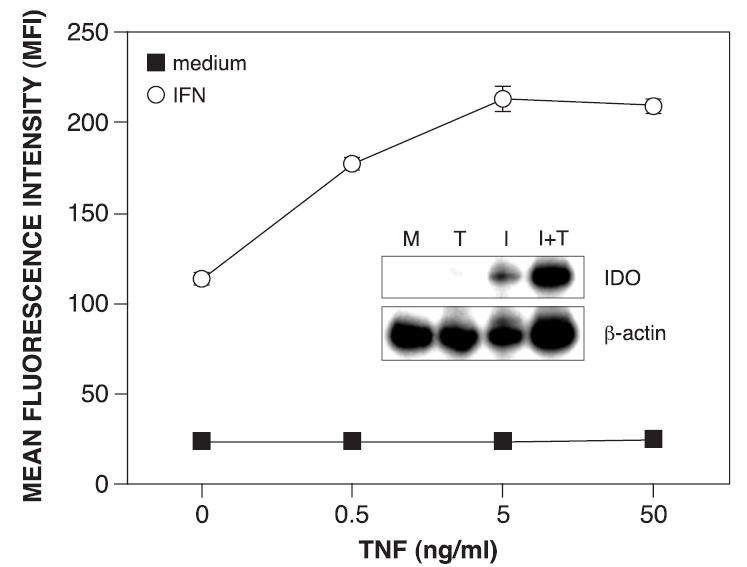

IFN-γ-induced IDO promoter activity is enhanced synergistically by TNF-α

To evaluate regions of the IDO upstream regulatory region responsible for transcriptional synergy in epithelial cells after treatment with IFN-γ and TNF-α, a reporter construct consisting of the IDO upstream regulatory region fused with the coding region for GFP was transfected into HeLa cells.(19) Changes in GFP expression in response to cytokine stimulation for 48 h were quantified by flow cytometry. Although TNF-α alone did not activate the IDO promoter (Fig. 2), it synergistically enhanced IFN-γ-induced promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner, with a peak at 5 ng/ml. In addition, quantification of IDO mRNA levels following stimulation with IFN-γ and TNF-α showed a synergistic increase (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with previous studies in which enzymatic activity was synergistically increased with the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α.(19)

FIG. 2.

TNF-α synergistically enhances IFN-γ-induced IDO transcription. HeLa cells were treated in triplicate with increasing concentrations of TNF-α alone (0.5–50 ng/ml) or combined with IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 48 h and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. The results (MFI ± SE) from one of two similar experiments are presented. (Inset) IDO mRNA levels were assessed by RT-PCR following 24 h treatment with medium alone (M), TNF-α at 5 ng/ml (T), IFN-γ at 10 ng/ml (I), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (I+T) in culture medium. β-Actin mRNA served as an internal control.

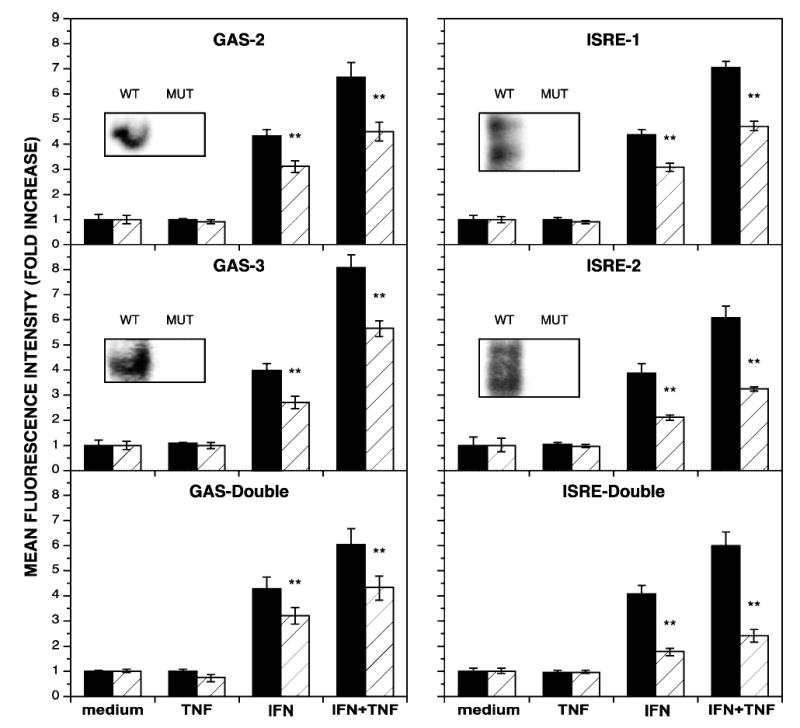

IFN-γ-responsive elements are critical for synergistic activation

TNF-α has been shown to increase IFN-γ-induced IDO transcription by enhancing recruitment of Stat1 and IRF-1 to GAS and ISRE sites, respectively.(19,26) Each of these sites contributes partially to the induction of IDO activity by IFN-γ,(17,23) and the relative contribution of each of these transcription factors/binding elements to the synergistic induction of IDO in response to combined IFN-γ and TNF-α has yet to be determined. To assess their role in synergy, base changes that abrogate binding to individual transcription factors were introduced into the IDO upstream regulatory region. EMSA analysis was performed with 20-mer probes consisting of either native or MUT sequences to confirm the absence of DNA-protein interactions following mutation of individual binding elements (Fig. 3, insets). Changes in GFP expression in response to IFN-γ, TNF-α or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α were quantified by flow cytometry and represented as the fold increase in MFI relative to treatment with medium alone (Fig. 3). Mutation of the GAS-2 site caused a significant decrease in GFP expression in response to IFN-γ, as expected, and also with the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 3, top left). Mutation of the GAS-3 site, recently determined to be a region involved in regulation,(19) caused a similar decrease in response to either IFN-γ alone or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 3, center left). Mutation of both GAS sites in the same construct yielded a similar decrease in GFP expression in response to IFN-γ or the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α to the mutation in either GAS site alone (Fig. 3, bottom left). This suggests that both GAS sites must be occupied by Stat1 and cooperate in some manner to maximally influence IDO transcriptional activation.

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ-responsive sites in the IDO regulatory region are critical to synergistic transcriptional activation. HeLa cells, transiently transfected with reporter constructs bearing either the wild-type regulatory region (WT, black bars) or a regulatory region with mutations (MUT, hatched bars) in the indicated response element(s) upstream of the GFP coding region, were cultivated with medium alone (medium), TNF-α at 5 ng/ml (TNF), IFN-γ at 10 ng/ml (IFN), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (IFN+TNF) for 48 h and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. The mean fold increase in MFI ± SE from three combined experiments is presented. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001. (Insets) EMSA analysis was performed with 20–mer probes corresponding to the indicated response element (WT) or with the mutations (MUT) described in Table 1. Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells treated with combined IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (5 ng/ml) for 4 h. Constructs with double mutations correspond to the same mutations in individual GAS or ISRE sites.

In native ISRE probes, binding of IRF-1 generates a doublet of bands corresponding to occupancy of one or both GAAA cores that are essential to binding.(27) Identical base substitutions in either individual ISRE site prevented DNA-protein interaction (Fig. 3, insets). The absence of IRF-1 binding to the ISRE-1 site resulted in a strong decrease in GFP expression in response to IFN-γ or the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 3, top right). Furthermore, a more pronounced effect on GFP expression was observed with the mutated ISRE-2 site (Fig. 3, center right). Mutation of both ISRE sites in a single construct caused the greatest decrease in transcriptional activation in response to IFN-γ either alone or in combination with TNF-α (Fig. 3, bottom left panel). These results suggest that although the increases in Stat1 binding to GAS sites contributes to IDO induction in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α, IRF-1 binding to ISRE sites is the more critical mechanism.

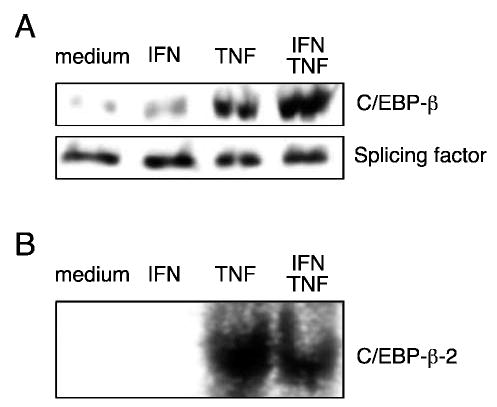

TNF-α increases C/EBP-β nuclear translocation

TNF-α enhancement of IFN-γ-induced IDO activity could be mediated in part by TNF-α-specific factors that independently contribute to transcriptional activation or cooperate with IFN-γ-specific factors. One such transactivator is C/EBP-β, which translocates to the nucleus in response to TNF-α in a number of cell and tissue types.(24) Because there are three consensus binding sites for C/EBP-β upstream of the IDO coding region (Table 1 and Fig. 1), this activator could contribute to synergistic activation of IDO. Nuclear levels of C/EBP-β were evaluated by immunoblot analysis in epithelial cells stimulated for 4 h with IFN-γ, TNF-α, combined IFN-γ and TNF-α, or medium alone. C/EBP-β was found to translocate to the nucleus in response to TNF-α; this localization was not significantly increased by the addition of IFN-γ (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Effect of TNF-α on C/EBP-β nuclear translocation. HeLa cells were cultivated with medium alone (medium), IFN-γ at 10 ng/ml (IFN), TNF-α at 5 ng/ml (TNF), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (IFN/TNF) in culture medium for 4 h. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared as described, separated on 12% polyacrylamide, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-C/EBP-β and Y12 antibody specific for constitutively expressed splicing factors to normalize for nuclear protein. (B) Nuclear extracts were incubated for 20 min with a radiolabeled 20–mer probe containing the C/EBP-β-2 site, separated on 5.5% polyacrylamide, and subjected to phosphorimaging.

To determine if C/EBP-β was capable of binding to the IDO regulatory region, all three consensus C/EBP-β sites upstream of IDO were analyzed for the ability to form a DNA-protein complex. Radiolabeled 20-mer probes corresponding to the individual consensus sequences upstream of IDO were analyzed with nuclear extracts from epithelial cells treated with IFN-γ, TNF-α, combined IFN-γ and TNF-α, or medium alone. Of the three C/EBP-β sites, only C/EBP-β-2 formed a complex with a nuclear protein in response to either TNF-α or the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 4B).

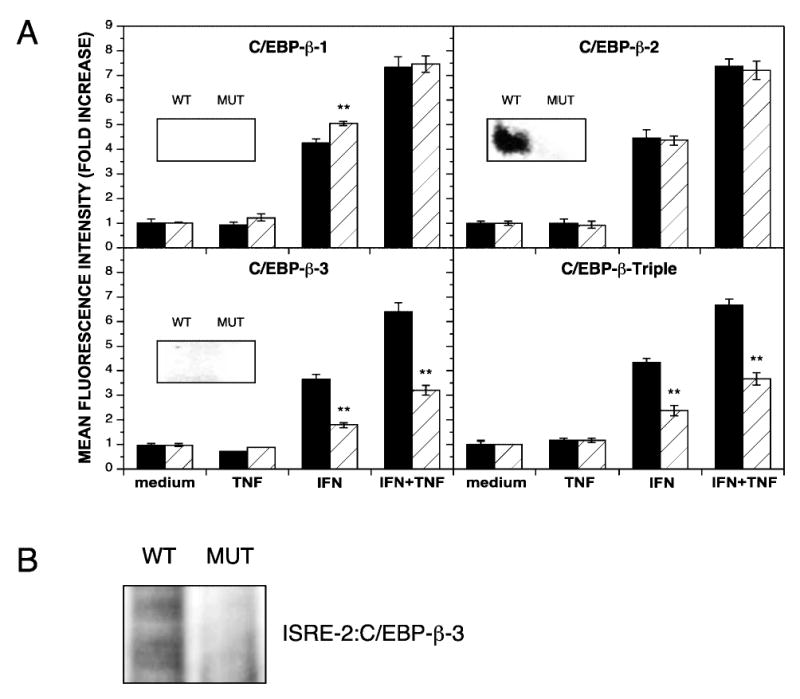

Analysis of C/EBP-β involvement in synergistic IDO induction

To establish whether C/EBP-β contributes to synergistic activation in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α, C/EBP-β sites in the IDO reporter construct were mutated to prevent C/EBP-β binding. EMSA analysis was performed with 20-mer probes corresponding to both native and mutated sequences to confirm that the modified sequences did not bind nuclear proteins (Fig. 5A, insets). The mutation of C/EBP-β-2 prevented the formation of a protein-DNA complex, and the mutations in C/EBP-β-1 and C-EBP-β-3 did not cause the formation of novel complexes. The effects of C/EBP-β site mutations on GFP expression in response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α were quantified and expressed as the fold increase in MFI relative to that observed with cells cultured in medium alone. Mutation of the C/EBP-β-1 site caused a modest increase in GFP expression compared with the WT regulatory region in response to IFN-γ alone but had no effect on the response to combined IFN-γ and TNF-α treatment (Fig. 5A, top left). Although C/EBP-β-2 bound nuclear protein in EMSA, mutation of the C/EBP-β-2 site did not change gene expression in response to any cytokine treatment compared with the WT regulatory region (Fig. 5A, top right). Interestingly, despite the absence of a detectable binding complex by EMSA, mutation of the C/EBP-β-3 site caused a very significant reduction in GFP expression after treatment with either IFN-γ alone or IFN-8 in combination with TNF-α (Fig. 5A, bottom left). A nearly identical reduction was exhibited with the construct in which all three C/EBP-β sites were altered, presumably due to the effect on transcription exhibited by the mutated C/EBP-β-3 site (Fig. 5A, bottom right).

FIG. 5.

Effect of mutating C/EBP-β sites in the IDO regulatory region. (A) HeLa cells, transiently transfected with reporter constructs bearing either the wild-type regulatory region (WT, black bars) or a regulatory region with mutations (MUT, hatched bars) in the indicated response element(s) upstream of the GFP coding region, were cultivated with medium alone (medium), TNF-α at 5 ng/ml (TNF), IFN-γ at 10 ng/ml (IFN), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (IFN+TNF) for 48 h and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. The fold increase in MFI ± SE from three combined experiments is presented. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001. (Insets) EMSA analysis was performed with 20–mer probes corresponding to the indicated response element (WT) or with the mutations (MUT) described in Table 1. Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells treated with combined IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (5 ng/ml) for 4 h. The triple mutant construct involves the same mutations in individual C/EBP-β sites. (B) C/EBP-β-3 mutation reduces IRF-1 binding to the ISRE-2 site. EMSA analysis was performed with radiolabeled 50–mer probes containing both the ISRE-2 and the native (WT) or mutated (MUT) C/EBP-β-3 sites, and nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells treated with combined IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (5 ng/ml) for 4 h. Binding reactions were separated on 5.5% polyacrylamide and subjected to phosphorimaging.

The reduction in transcriptional activation achieved with the mutation of the C/EBP-β-3 was nearly the same as that obtained with the ISRE-2 mutation (Fig. 3, center right). Furthermore, this reduction was observed with IFN-γ alone, a condition in which C/EBP-β is not abundant in the nucleus (Fig. 4). As the C/EBP-β-3 and ISRE-2 sites are immediately adjacent (Fig. 1), this suggests the possibility that the ISRE-2 site conformation was distorted by changes in the C/EBP-β-3 site, preventing the binding of IRF-1. Indeed, binding of IRF-1 to short ISRE-containing probes in vitro is relatively weak(19) despite its strong influence on transcriptional activation (Fig. 3). To determine if the mutated C/EBP-β-3 site interferes with IRF-1 binding to ISRE-2, EMSA analysis was performed using a 50-mer probe containing both the ISRE-2 site and either the native or mutated C/EBP-β-3 site (Fig. 5B). When the C/EBP-β-3 mutation was present, the intensity of the probe-protein complex was considerably reduced, indicating that the DNA sequence within the C/EBP-β-3 site does influence binding to the ISRE-2 site.

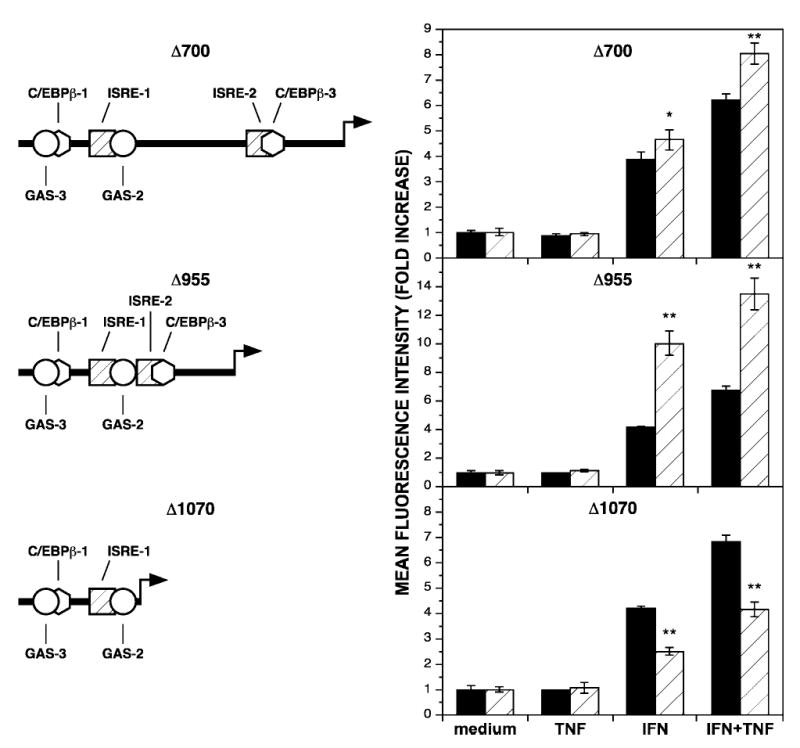

IFN-γ-responsive regions alone mediate for synergistic transcriptional activation

Enhancement of the IFN-γ-induced signal transduction pathways has been shown to mediate the synergistic transcriptional activation observed with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Furthermore, C/EBP-β appears to play no role in this synergy. To rule out a contribution of other regulatory elements between the promoter proximal and promoter distal IFN-γ-responsive sites, large stretches of intervening sequence were deleted, and the effects on GFP expression were quantified. Deletion of 700 nt between IFN-γ-responsive sites had no effect on GFP expression in response to IFN-γ and maintained the synergistic response to IFN-γ combined with TNF-α (Fig. 6, top). However, when 955 nt between the IFN-γ-responsive regions were deleted, a >2-fold increase in IFN-γ-inducible GFP expression was observed. Furthermore, synergistic expression was maintained with combined IFN-γ and TNF-α treatment (Fig. 6, center). Further deletion totaling 1070 nt nucleotides and encompassing the ISRE-2 and C/EBP-β-3 sites reduced expression relative to the native regulatory region but synergistic expression was still driven from the remaining IFN-γ-responsive sites (Fig. 6, bottom).

FIG. 6.

DNA sequence between IFN-γ-responsive sites does not influence synergistic transcriptional activation. (Left) Scaled diagrams of the deletions in the IDO regulatory region (compare with the undeleted diagram in Fig. 1). (Right) HeLa cells transiently transfected with reporter constructs bearing either the wild-type regulatory region (black bars) or a regulatory region with deletions (hatched bars) of the indicated length of sequence upstream of the GFP coding region were cultivated with medium alone (medium), TNF-α at 5 ng/ml (TNF), IFN-γ at 10 ng/ml (IFN), or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α (IFN+TNF) for 48 h and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. The fold increase in MFI ± SE from three combined experiments is presented. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001.

That these deletions did not diminish the synergistic response to combined cytokine treatment supports the view that synergistic transcriptional activation of IDO expression is regulated primarily by enhanced IFN-γ-induced signal transduction. Furthermore, the deletion of 1070 nt demonstrates that simply moving the 5′-end of the regulatory region closer to the start of transcription in and of itself does not increase transcriptional activation and suggests the possibility that the reduction of the distance between distal and proximal IFN-γ-responsive sites allows for formation of a more efficient activation complex, perhaps through activator-activator interactions. To address whether activators bound at GAS and ISRE sites cooperate in a manner that is dependent on helical phasing,(28) an increasing series of random nucleotides (3, 5, 10, 15, and 19 nt) was added separately at the junction where the 955 nt were deleted. In response to the combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α, GFP expression decreased with the addition of 5 nt, representing a half-helical turn (Table 2). This effect on decreasing GFP expression was greater with the addition of 15 nt, which also created a half-helical turn between IFN-γ-responsive sites. When 10 or 19 nt, representing nearly one or two full-helical turns were inserted between IFN-γ-responsive sites, GFP expression was similar to that obtained with the Δ955 construct.

Table 2.

Effect of Helical Phasing on GFP Expression

HeLa cells transiently transfected with reporter constructs bearing either the regulatory region in the Δ955 construct or additions of the indicated number of nucleotides were cultivated with combined IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (5 ng/ml) for 48 h and analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry.

Mean fold increase in GFP expression (MFI) relative to the Δ955 construct, from three pooled experiments.

DISCUSSION

The IFN-γ-inducible IDO gene is expressed synergistically in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α. This synergistic expression is regulated at the level of transcription, which can be demonstrated experimentally in two different ways. First, TNF-α was shown to increase the amount of IDO mRNA in IFN-γ-treated epithelial cells. Second, when using a transcriptional reporter plasmid containing the IDO regulatory region upstream of the GFP coding region, enhanced production of GFP has been demonstrated. Maximal synergistic enhancement of IDO induced by IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) was obtained with 5 ng/ml of TNF-α, a concentration within the physiologic range expected during an inflammatory response.

Several mechanisms involved in transcriptional activation of the IDO gene by IFN-γ have been characterized previously.(17,18, 22,23) First, Stat1 translocates to the nucleus and binds upstream of the IDO coding region at GAS-2 and GAS-3 sites by 4 h. Second, IRF-1 is synthesized de novo following stimulation with IFN-γ and binds at ISRE-1 and ISRE-2 sites by 4 h. Both these activities have been shown to be increased in epithelial cells in in vitro assays using nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with IFN-γ and TNF-α.(19,26)

One major aim of this study was to determine the importance of enhanced IFN-γ-induced signal transduction pathways to synergistic transcriptional activity and the relative individual contributions of increases in Stat1 or IRF-1 to the synergy. Given the role of IFN-γ-responsive activators in IDO induction, it was expected that blocking their binding upstream of the IDO coding region would diminish synergistic expression. However, the potent decrease in GFP expressed after mutation of ISRE sites suggests that IRF-1 contributes more to IDO induction than Stat1 binding to GAS sites and that the increase in binding of IRF-1 to ISRE sites is the dominant force driving synergistic expression with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Mutation of the ISRE-1 site caused nearly the same decrease in GFP expression as both of the GAS sites after stimulation with IFN-γ or combined IFN-γ and TNF-α. Furthermore, mutation of the ISRE-2 site resulted in a more drastic reduction in GFP expression than mutation of the ISRE-1 site. There are two possible explanations that can be drawn from this result. The first is that the ISRE-2 is a stronger enhancer. This is consistent with the stronger interaction of IRF-1 with ISRE-2 in EMSA analysis,(19) as well as its greater effect in a mutational analysis of ISRE sites in an IDO-CAT reporter plasmid in response to IFN-γ alone.(23) The second possibility is that the ISRE-2 enhancer functions as a hinge or platform for activator-induced three-dimensional changes in the DNA topology as a result of interactions with activators bound at the distal end of the regulatory region. However, although the ISRE-2 site exhibits relatively stronger binding than the ISRE-1 site in in vitro binding assays, this may not be reflective of conditions within an intact cell. It is possible that in vivo IRF-1 interaction with the ISRE-1 site is strengthened by nearby protein interactions and, thus, exhibits a greater degree of binding than the ISRE-2 site.

Stat1 binding to GAS sites also appears to contribute to synergistic expression, both directly and indirectly. When both ISRE sites were mutated, there remained a synergistic response to combined IFN-γ and TNF-α. That mutation of the GAS sites in the IDO regulatory region also reduces transcriptional activation suggests that Stat1 binding to the GAS sites contributes directly to IDO synergy. However, GAS sites probably play a more important, indirect role by increasing IRF-1 production. A single GAS site upstream of IRF-1 has been shown to be a strong enhancer of IRF-1 expression, and increased binding of Stat1 to the IRF-1 regulatory region has been shown in response to combined IFN-γ and TNF-α.(20,21)

C/EBP-β, a protein shown to be TNF-α responsive in a number of other cell and tissue types,(24) was shown to translocate to the nucleus in epithelial cells after stimulation with TNF-α, and the addition of IFN-γ had no significant effect on its translocation. In EMSA analysis, only a probe comprising the C/EBP-β-2 site, one of three consensus C/EBP-β sites in the IDO regulatory region, was bound by nuclear C/EBP-β. However, disruption of the C/EBP-β-2 site had no effect on GFP expression in response to cytokine stimulation. This result strongly suggests that C/EBP-β is not involved in synergistic IDO expression.

Although no protein binding to the C/EBP-β-1 and C/EPP-β-3 sites was detected by EMSA, the same base changes that disrupted binding to the C/EBP-β-2 site were introduced in individual reporter constructs. This was to rule out the possibility that undetected complexes might participate in binding within a complete regulatory region, where other protein-protein interactions might take place. Mutation of the C/EBP-β-1 site did not decrease gene expression in response to any cytokine treatment. Surprisingly, mutation of the C/EBP-β-3 site caused a significant decrease in both IFN-γ-specific and synergistic gene expression. That IFN-γ alone did not lead to translocation of C/EBP-β into the nucleus suggested that mutation of the C/EBP-β-3 site had a nonspecific effect on the ISRE-2 site, perhaps by altering the topology of the local DNA in a way that did not favor IRF-1 association. It is possible that altering the sequence immediately downstream of ISRE-2 distorts secondary structure in the DNA necessary to strengthen IRF-1 interaction. Indeed, others have found that sequences flanking the consensus sequence of an enhancer element can influence binding to the element.(29) The proximity of the two enhancer sites and the similarity of the effects of the C/EBP-β-3 mutation and the ISRE-2 mutation (Figs. 5 and 3, respectively) are consistent with this possibility. Furthermore, in vitro binding of IRF-1 to short DNA probes is relatively weak(19) despite its greater effect of IDO activation (Fig. 3). This suggests that the conformation of nucleic acid in the complete IDO regulatory region is important for strengthening IRF-1 binding. After elimination of both the C/EBP-β-3 and ISRE-2 sites in the Δ1070 deletion mutant, TNF-α still synergistically enhanced GFP expression, albeit reduced because of the loss of the ISRE-2 site. This indicates that TNF-α-triggered binding of C/EBP-β at the C/EBP-β-3 site is unrelated to the synergistic induction of IDO in response to IFN-γ and TNF-α.

To establish that other sequences within a large stretch of DNA between IFN-γ-responsive regions are not important in conferring synergistic transcriptional activation, a series of large deletions were made. Deletion of 700 nt between IFN-γ-responsive sites did not diminish the level of GFP expression and, in fact, slightly increased expression. However, when 955 intervening nucleotides were deleted, GFP expression was increased >2-fold above that achieved by the native regulatory region in response to IFN-γ alone or to IFN-γ and TNF-α combined. This condensed regulatory region allowed for greater activation of transcription, possibly because of cooperativity between bound IFN-γ-responsive sites and multiple activators interacting with the general transcription machinery, and is suggestive of enhanceasome structure.(30) Both positional and cooperative effects have been established for binding elements within the upstream IFN-γ-responsive site.(17)

Although the GAS-1 element is ineffective in its original location within the upstream IFN-γ-responsive site, it fully supports a response to IFN-γ when located in the position of the GAS-2 element. Furthermore, increasing the distance between GAS-2 and ISRE-1 diminished IFN responsiveness, indicating some degree of cooperativity between these elements. These positional effects are more pronounced within the Δ955 construct, in which the upstream and downstream IFN-γ-responsive sites have been brought into proximity. The cooperative actions within this construct appear to be sensitive to helical phasing, similar to that described for the IFN-γ enhanceasome.(28) This was demonstrated by the additions of 5 nt and 15 nt, respectively, resulting in a half-helical turn insertion that likely disrupted cooperativity and thus reduced GFP expression. This was much more pronounced with the addition of 15 nt, possibly suggesting that proper spacing may also be involved to allow for favorable folding or bending of DNA in a manner that does not disrupt protein-protein interactions. Preservation of helical phasing following additions of 10 nt and 19 nt maintained GFP expression at levels comparable with that achieved with the Δ955 construct. It is curious that elimination of intervening sequences between the IFN-γ-responsive sites results in more efficient transcriptional activation. It may be that elements within this region are used under other conditions to provide additional regulation to the IDO gene. Alternatively, one might speculate that the DNA between IFN-γ-responsive sites has evolutionarily been retained to limit the amount of IDO enzyme activity achieved within a cell. The effect of too much IDO activity would be cell death as a result of tryptophan depletion. This stretch of DNA does not include enhancers that are important to IDO induction by IFN-γ or TNF-α but, instead, could exist to limit the amount of IDO produced by a cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Hughes at Miami University for his assistance with statistical analysis. This study was supported by grant No. AI45836 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (J.M.C.).

References

- 1.BYRNE GI, LEHMANN LK, LANDRY GJ. Induction of tryptophan catabolism is the mechanism for gamma-in-terferon-mediated inhibition of intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication in T24 cells. Infect Immun. 1986;53:347–351. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.347-351.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PFEFFERKORN ER, REBHUN S, ECKEL M. Characterization of an indoleamine 2,3–dioxygenase induced by gamma-interferon in cultured human fibroblasts. J Interferon Res. 1986;6:267–279. doi: 10.1089/jir.1986.6.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SHIMIZU T, NOMIYAMA S, HIRATA F, HAYAISHI O. Indoleamine 2,3–dioxygenase: purification and some properties. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:4700–4706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.PFEFFERKORN ER. Interferon-γ blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;81:908–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SCHMITZ JL, CARLIN JM, BORDEN EC, BYRNE GI. Beta-interferon inhibits Toxoplasma gondii growth in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3254–3256. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3254-3256.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SHEMER Y, SAROV I. Inhibition of the growth of Chlamydia trachomatis by human gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1985;48:592–596. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.592-596.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SUMMERSGILL JT, SAHNEY NN, GAYDOS CA, RAMIREZ JA. Inhibition of Chlamydia pneumoniae growth in Hep-2 cells pretreated with gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2801–2803. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2801-2803.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BABCOCK TA, CARLIN JM. Transcriptional activation of indoleamine dioxygenase by interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α in interferon-treated epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2000;12:588–594. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CURRIER AR, ZIEGLER MH, RILEY MM, BABCOCK TA, TELBIS VP, CARLIN JM. Tumor necrosis factor-α and lipopolysaccharide enhance interferon-induced antichlamydial indoleamine dioxygenase activity independently. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:369–376. doi: 10.1089/107999000312306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BAVOIL PM, HSIA RC, RANK RG. Prospects for a vaccine against Chlamydia genital disease. I Microbiology and pathogenesis. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1996;94:5–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MOULDER JW. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WARD ME. The immunobiology and immunopathology of chlamydial infections. APMIS. 1995;103:769–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.BOEHM U, KLAMP T, GROOT M, HOWARD JC. Cellular responses to IFN-γ. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BRISCOE J, KOHLHUBER F, MULLER M. Jaks and Stats branch out. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:336–340. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DARNELL JE, Jr, KERR IM, STARK GM. Jak-Stat pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LEONARD WJ, O’SHEA JJ. Jaks and Stats: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CHON SY, HASSANAIN HH, GUPTA SL. Cooperative involvement of interferon regulatory factor 1 and p91 (Stat1) response elements in interferon-γ-inducible expression of human indoleamine 2,3–dioxygenase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17247–17252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CHON SY, HASSANAIN HH, PINE R, GUPTA SL. Involvement of two regulatory elements in interferon-γ-regulated expression of human indoleamine 2,3–dioxygenase gene. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1995;15:517–526. doi: 10.1089/jir.1995.15.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ROBINSON CM, SHIREY KA, CARLIN JM. Synergistic transcriptional activation of indoleamine dioxygenase by IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:413–421. doi: 10.1089/107999003322277829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PINE R. Convergence of TNFα and IFNγ signaling pathways through synergistic induction of IRF-1/ISGF-2 is mediated by a composite GAS/κB promoter element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4346–4354. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.YOSHIHIRO O, SCHREIBER RD, HAMILTON TA. Synergy between interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α in transcriptional activation is mediated by cooperation between signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and nuclear factor κB. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14899–14907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DU MX, SOTERO-ESTEVA WD, TAYLOR MW. Analysis of transcription factors regulating induction of indoleamine 2,3–dioxygenase by IFN-γ. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:133–142. doi: 10.1089/107999000312531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.KONAN KV, TAYLOR MW. Importance of the two interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE) sequences in the regulation of the human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19140–19145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AKIRA S, ISSHIKI H, NAKAJIMA T, KINOSHITA S, NISHIO Y, HASHIMOTO S, NATSUKA S, KISHI-MOTO T. A nuclear factor for IL-6 gene (NF-IL-6) Interleukins: Mol Biol Immunol. 1992;51:299–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GUO Z, GUTIERREZ C, HEINE U, SOGO JM, DEPAMPHILIS ML. Origin auxiliary sequences can facilitate initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro as they do in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3593–3602. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.HAN Y, ROGERS N, RANSOHOFF RM. Tumor necrosis factor-α signals to the IFN-γ receptor complex to increase Stat1α activation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:731–740. doi: 10.1089/107999099313578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ESCALANTE CR, YIE J, THANOS D, AGGARWAL AK. Structure of IRF-1 with bound DNA reveals determinants of interferon regulation. Nature. 1998;391:103–106. doi: 10.1038/34224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MANIATIS T, FALVO JV, KIM TH, KIM TK, LIN CH, PAREKH BS, WATHELET MG. Structure and function of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:609–620. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SEIDEL HM, MILOCCO LH, LAMB P, DARNELL JE, Jr, STEIN RB, ROSEN J. Spacing of palindromic half sites as a determinant of selective Stat (signal transducers and activators of transcription) DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3041–3045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CAREY M. The enhanceosome and transcriptional synergy. Cell. 1998;92:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]