Abstract

Anther development involves the formation of several adjacent cell types required for normal male fertility. Only a few genes are known to be involved in early anther development, particularly in the establishment of these different cell layers. Arabidopsis thaliana BAM1 (for BARELY ANY MERISTEM) and BAM2 encode CLAVATA1-related Leu-rich repeat receptor-like kinases that appear to have redundant or overlapping functions. We characterized anther development in the bam1 bam2 flowers and found that bam1 bam2 anthers appear to be abnormal at a very early stage and lack the endothecium, middle, and tapetum layers. Analyses using molecular markers and cytological techniques of bam1 bam2 anthers revealed that cells interior to the epidermis acquire some characteristics of pollen mother cells (PMCs), suggesting defects in cell fate specification. The pollen mother-like cells degenerate before the completion of meiosis, suggesting that these cells are defective. In addition, the BAM1 and BAM2 expression pattern supports both an early role in promoting somatic cell fates and a subsequent function in the PMCs. Therefore, analysis of BAM1 and BAM2 revealed a cell–cell communication process important for early anther development, including aspects of cell division and differentiation. This finding may have implications for the evolution of multiple signaling pathways in specifying cell types for microsporogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate cell division and differentiation is an essential goal for developmental biologists. In plants, cellular differentiation occurs as an interplay between a cell's lineage and its relative position within a structure (Szymkowiak and Sussex, 1996; Berger et al., 1998; Scheres and Benfey, 1999). The relative importance of these determining factors appears to vary depending on the specific developmental process. For example, analysis using chimeras between Solanum luteum and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) leaf cell layers indicated that trichome development was determined by the genotype of the differentiating L1 cells (autonomous development), whereas leaf shape was controlled by the genotype of the neighboring cell layer (nonautonomous development) (Jorgenson and Crane, 1927; Szymkowiak and Sussex, 1996).

For several aspects of plant development, cell fate specification has been shown to rely more on positional information than on cell lineage (Szymkowiak and Sussex, 1996). For instance, it was shown in both leaf and root that cells are able to respond to a new position and differentiate accordingly when they are displaced from one layer into an adjacent layer, irrespective of their lineages (Stewart and Dermen, 1975; van den Berg et al., 1995). Positional signals can be mediated by either apoplastic mechanisms, via receptors, or symplastic mechanisms, through plasmodesmata (Hake and Freeling, 1986; Fletcher et al., 1999; Rojo et al., 2002; Kwak et al., 2005). Apoplastic cell–cell communication is often achieved via receptor–ligand interactions (Bergmann, 2004). For example, the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) SCRAMBLED is required for normal epidermal cell type patterning in the Arabidopsis thaliana root (Kwak et al., 2005). In addition, the ERECTA (ER) and ERECTA-LIKE1 (ERL1) and ERL2 genes encode LRR-RLKs that control position-dependent guard cell differentiation (Shpak et al., 2005). Hence, positional cues via receptor-mediated intercellular signaling from adjacent cells help control cell division and differentiation (Hake and Freeling, 1986; Berger et al., 1998; Kwak et al., 2005).

In the male reproductive organ of flowering plants, the anther, the differentiation of sporogenous and parietal cell types is essential for the propagation of the species. In Arabidopsis, development of the male gametophytes, the pollen grains, occurs within the four lobes of the anthers (Goldberg et al., 1993; Sanders et al., 1999). Within each lobe, cells divide and differentiate to form distinct somatic cell layers surrounding the developing reproductive cells, or the pollen mother cells (PMCs). The proper formation and development of these somatic cell layers is critical for the development and eventual release of pollen grains (Mariani et al., 1990, 1991; Denis et al., 1993; Ross et al., 1996; Sanders et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2002; Ma, 2005; Hord and Ma, 2006).

Anther development in Arabidopsis has been divided into specific stages according to morphological characteristics (Sanders et al., 1999). In the emergent anther primordium (stage 1), there are three distinct cell layers derived from the floral meristem: from outer to inner they are L1, L2, and L3 (Sanders et al., 1999). The four corners of the anther primordia develop into the four lobes during further anther development, as described previously (Goldberg et al., 1993; Sanders et al., 1999). The L1 layer develops into the epidermis, and the L2-derived cell layers develop via a series of periclinal (parallel to the adjacent outer surface and creating additional cell layers) and anticlinal (perpendicular to the outer surface and increasing cell number in a layer) cell divisions. At stage 2, L2 cells called archesporial cells divide periclinally to form primary parietal (outer) and primary sporogenous (inner) cells. Then at stage 3, periclinal division of the primary parietal cells forms the inner and outer secondary parietal cells. Subsequently, in each of the four anther lobes, cells of one of the secondary parietal layers divide again at stage 4, resulting in three somatic layers at stage 5: endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum, which immediately surrounds the L2-derived PMCs. The tapetum is important for providing the developing pollen with nutrients and materials (Mariani et al., 1990, 1991; Denis et al., 1993). The L3 layer gives rise to the vascular and connective tissues of the anther.

To date, only a few genes are known to be involved in early anther cell division and cell differentiation events, including SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE (SPL/NZZ), EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1/EXTRA SPOROGENOUS CELLS (EMS1/EXS), SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS1 (SERK1), SERK2, and TAPETUM DETERMINANT1 (TPD1) (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2003, 2005; Ito et al., 2004; Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005; Ma, 2005; Hord and Ma, 2006). SPL/NZZ was shown to promote microsporogenesis under the control of AGAMOUS in whorl three floral organs (Ito et al., 2004). In the spl and nzz mutants, the L2-derived cells do not develop properly and are unable to form PMCs (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). The detailed descriptions of the spl and nzz mutants differ somewhat. The spl mutant was reported as having primary sporogenous and secondary parietal cells (Yang et al., 1999), whereas the description that the nzz mutant forms an undifferentiated mass of archesporial cells (Schiefthaler et al., 1999) suggests that SPL/NZZ may act at the stage when the archesporial cells divide to form primary sporogenous cells and primary parietal cells. SPL/NZZ has been cloned and encodes a putative transcription factor (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999).

The ems1/exs, serk1 serk2, and tpd1 mutations affect cellular differentiation by altering cell fate at a later stage than spl/nzz (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2003; Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005). Instead of forming the four normal L2-derived cell types, these mutants form endothecium, middle layer cells, and a greater than normal number of PMCs. The mutant anther lobes completely lack the nutritive tapetum layer. Although the excess PMCs enter meiosis and undergo nuclear division, they fail to complete cytokinesis and degrade completely by anther stage 7 (Ma, 2005; Hord and Ma, 2006). EMS1/EXS, SERK1, and SERK2 encode LRR-RLKs, indicating an essential role for a position-dependent intercellular signaling event (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005). TPD1 encodes a small putatively secreted protein that may act in the same pathway as EMS1/EXS and SERK1/2 (Yang et al., 2003, 2005; Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005). In addition to its role in anther development, SERK1 was initially shown to promote somatic embryogenesis (Schmidt et al., 1997; Hecht et al., 2001).

LRR-RLKs constitute one of the largest gene families in Arabidopsis; however, relatively few of these genes have known functions (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001, 2003). For instance, CLAVATA1 (CLV1) is a LRR-RLK that acts with CLV3 to limit the size of the shoot apical and floral meristems and may promote the transition of central zone cells to peripheral zone cells (Clark et al., 1996; Fletcher et al., 1999; Gallois et al., 2002; Rojo et al., 2002; Lenhard and Laux, 2003). In addition, BRASSINOLIDE INSENSITIVE1 (BRI1) and BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE (BAK1/SERK3) are involved in the brassinosteroid signaling pathway (He et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Li et al., 2002; Nam and Li, 2002).

BAM1 (for BARELY ANY MERISTEM) and BAM2 encode LRR-RLKs (DeYoung et al., 2006) that share high levels of amino acid sequence identity and form a four-gene monophyletic clade along with CLV1 and BAM3 (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001; DeYoung et al., 2006). Single mutants in these genes do not exhibit any obvious morphological defects, indicating that they have redundant functions (DeYoung et al., 2006). By contrast, bam1 bam2 double mutants display multiple developmental defects, including a reduction of meristem size, altered leaf shape, size, and venation, male sterility, and reduced female fertility (DeYoung et al., 2006). Here, we show that the bam1 and bam2 mutations affect normal cell division and differentiation during early anther development. The bam1 bam2 double mutant does not produce the somatic cell layers that are derived from archesporial cells; instead, they only form cells that resemble PMCs, which then degrade before completing meiosis. The BAM1 and BAM2 genes are expressed in the area of archesporial cells as early as stage 2 and also preferentially in sporogenous cells and PMCs at later stages. The very early BAM1/2 expression pattern and the early morphological defects suggest that these genes promote cell division and differentiation, including the specification of the parietal cells that give rise to the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum. BAM1/2 expression in sporogenous cells and PMCs and the degeneration of PMCs in the bam1 bam2 double mutant suggest that these genes also play a role in the development and/or function of PMCs.

RESULTS

Anther Development in the bam1 bam2 Mutant Is Abnormal

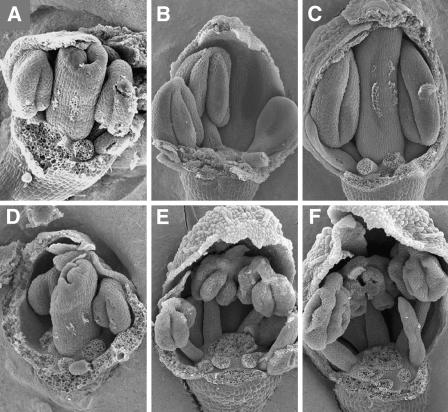

bam1 bam2 mutant plants are male sterile, and the mutant anthers fail to produce pollen (DeYoung et al., 2006). To better understand the overall morphological differences between the mutant and wild-type anthers, scanning electron microscopy images of dissected buds were examined. At approximately flower stage 8 (Smyth et al., 1990), the size and shape of wild-type and mutant anthers appeared similar (Figures 1A and 1D). Subsequently, mutant anthers had lobes that appeared less full (Figures 1B and 1E) at approximately late stage 9, although the stage of the mutant flowers was difficult to determine at this resolution because of the abnormal size and morphology of other floral organs. Close to stage 10, the mutant anthers had a shriveled appearance, suggesting that the locules had collapsed (Figures 1C and 1F). Anther development appeared to be defective at or before flower stage 9, during which several key developmental processes occurred, including the establishment of the five cell layers and meiosis. The anther morphology of bam1-1 bam2-1 (data not shown) is similar to that of bam1-3 bam2-3.

Figure 1.

Scanning Electron Microscopy Images of Dissected Buds.

Several floral organs have been removed to allow for better visualization of the anther defects.

(A) to (C) Wild-type (Ler) floral buds.

(A) A floral bud at stage 8 (anther stage 4).

(B) A floral bud at stage 9 (anther stage is between 5 and 7).

(C) A floral bud at stage10 (anther stage is between 7 and 8).

(D) to (F) bam 1-3 bam 2-3 double mutant (Ler) floral buds.

(D) A floral bud near stage 8. The anthers appear similar to those of the wild type (A).

(E) A mutant floral bud near stage 9 showing anthers that are less full than the wild type (B).

(F) A floral bud near stage 10, with anthers that have apparently collapsed locules.

bam1 bam2 Is Defective in Formation of Anther Cell Layers

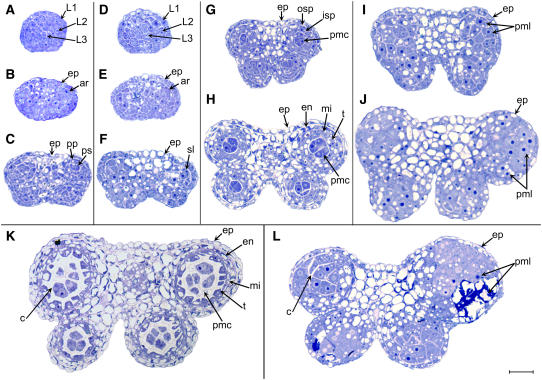

To better understand the defect in anther development, we prepared and analyzed transverse sections of wild-type and bam1-3 bam2-3 anthers (Figure 2). At stage 1 of anther development, cells from all three cell layers, L1, L2, and L3, appeared slightly larger in the bam1 bam2 anthers than in the wild type (Figures 2A and 2D). At the same time, the average number (±sd) of subepidermal cells (L2 and L3) in a cross section of the stage 1 bam1 bam2 anther (27.9 ± 3.5; n = 11) was slightly smaller than the number in the wild type (Landsberg erecta [Ler]) (31.9 ± 5.6; n = 44). This reduction is much less dramatic than the size reduction of the bam1 bam2 inflorescence meristem (DeYoung et al., 2006). At stage 2, both wild-type and mutant anthers appeared to have a similar structure and overall cell patterning, but the cells in the mutant remained slightly larger than those of the wild type (Figures 2B and 2E). At anther stage 3, the wild-type anther has well-defined lobes and the archesporial cells have undergone a periclinal cell division, forming the primary sporogenous and primary parietal cells, which lie approximately parallel to the epidermis at the outermost part of each lobe (Figure 2C). Mutant anthers at stage 3 appeared to have fewer and larger cells in each lobe (Figure 2F). Although evidence of a periclinal cell division was observed occasionally, in general there were no clearly defined primary parietal and primary sporogenous cells. At stage 4, wild-type sporogenous cells are visible at the center of each lobe (Figure 2G). At this stage, the primary parietal cells have divided periclinally to form the outer secondary parietal and the inner secondary parietal cells. At stage 4 in the mutant, the width and thickness of the anther began to appear substantially greater than the wild-type dimensions (Figure 2I). Although at times there appeared to have been cell divisions with orientations close to periclinal and anticlinal, the mutant anthers still did not form the cell layers that are characteristic of normal anthers, and the cellular pattern appeared to be disorganized.

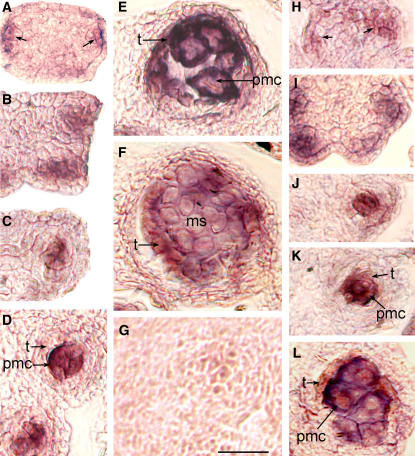

Figure 2.

Semithin Sections of Anthers.

(A) to (C), (G), (H), and (K) Wild type (Ler).

(D) to (F), (I), (J), and (L) bam 1-3 bam 2-3 (Ler).

(A) A wild-type anther at stage 1.

(B) A wild-type anther at stage 2.

(C) A wild-type anther at stage 3.

(D) A mutant anther at stage 1.

(E) A mutant anther at stage 2.

(F) A mutant anther at stage 3 does not have normally organized L2-derived cell layers.

(G) A wild-type anther at stage 4.

(H) A wild-type anther at stage 5 showing five distinct cell layers in each lobe.

(I) A mutant anther at stage 4 has the epidermis, but the distinct developing cell layers are missing.

(J) A mutant anther at stage 5, which appears to completely lack the normal subepidermal cell layers. The cells in each lobe appear enlarged.

(K) A wild-type anther at stage 6 showing thick callose surrounding the meiotic sporogenous cells.

(L) A mutant anther at stage 6; the L2-derived cells begin to degrade.

ar; archesporial cells; c, callose; en, endothecium; ep, epidermis; isp, inner secondary parietal cells; mi, middle layer; osp, outer secondary parietal cells; pmc, pollen mother cells; pml, pollen mother-like cells; pp, primary parietal cells; ps, primary sporogenous cells; sl, sporogenous-like cells; t, tapetal cells. Bar = 20 μm; all panels are of the same magnification.

In the wild-type anther at stage 5, the PMCs are formed at the center of each lobe and are surrounded sequentially, from inner to outer, by the tapetum, middle layer, and endothecium, with the epidermis encasing the entire anther (Figure 2H). With the exception of the epidermis, the mutant anthers never formed these organized sporophytic cell layers (Figure 2J). Instead, their enlarged cells appeared slightly fewer in number (see below) and less organized. In addition, the nuclei of these cells appeared unusually large, a characteristic of meiotic cells. Meiosis in the wild type commences during anther stage 6, and the PMCs become isolated from each other and from the tapetum as a thick callose wall is formed around them (Figure 2K). Some cells within the bam1 bam2 anther lobes had callose around them, whereas some other cells exhibited signs of degradation (Figure 2L). Eventually, most or all of the L2-derived cells in the mutant degraded, causing the lobes to collapse and the anther to appear shriveled (Figure 1F).

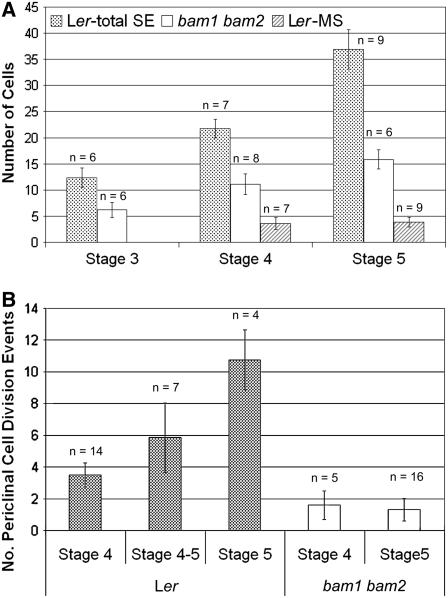

The cells in the bam1 bam2 mutant anthers appeared larger and fewer in number than their wild-type counterparts. To obtain more quantitative information, the number (Figure 3A) and dimensions of the L2-derived cells in each lobe were analyzed using cross sections. At stage 5 in the wild type, the average number ± sd of PMCs per lobe was 3.8 ± 0.9, and the total number of L2-derived cells per lobe was 36.9 ± 3.8 (Figure 3A). By contrast, the number of L2-derived cells in the double mutant was 15.8 ± 1.8. Although this number is obviously smaller than the total number of L2-derived cells in the wild-type, it is also much larger than the average number of PMCs per lobe in the wild type, by greater than fourfold. The average length (16.0 ± 5.4 μm; parallel to the epidermis) and height (14.1 ± 5.0 μm; perpendicular to the epidermis) of the mutant cells were significantly greater than those of wild-type PMCs (5.8 ± 2.5 μm long, 4.7 ± 2.1 μm high). Interestingly, although the length of the mutant juxtaepidermal cells at stage 5 did not differ significantly from those of the corresponding wild-type cells (16.0 ± 5.4 μm for the mutant and 16.1 ± 4.2 μm for the wild type), the height of the cells was significantly greater in the mutant (14.1 ± 5.0 μm for the mutant and 6.9 ± 1.6 μm for the wild type). Together, these observations indicate that cell division and/or cell expansion were altered in the bam1 bam2 mutant. In particular, it seems that cells in the double mutant expanded without some of the cell divisions that normally produced the secondary parietal cells or subsequent cell layers in the wild type.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Number of Cells and Cell Division Events between Wild Type and bam1 bam2.

(A) Average numbers of cells per cross section in each lobe.

(B) Average numbers of cell division events per cross section in each lobe that were parallel to the epidermis, between the epidermis and the PMCs.

MS, PMCs; SE, subepidermal L2-derived cells. Error bars indicate sd.

The cell layers in the anther are normally formed by periclinal cell divisions of the subepidermal cells. To better quantify the cell division defect, we counted the number of cell walls per lobe, interior to the epidermis and exterior to the PMCs, that appeared to have arisen via a periclinal cell division for stages 4 to 5 (Figure 3B). The wild type at stage 4 had an average of 3.5 ± 0.8 periclinal cell division events per lobe, which was not statistically different from the lobes transitioning from stage 4 to 5, which had 5.9 ± 2.2. However, at stage 5, the wild type had an average of 10.8 ± 1.9 periclinal cell division events per lobe, which was significantly higher than both stage 4 and stage 4 to 5. In the bam1 bam2 mutant, the numbers of periclinal cell divisions were similarly small at stages 4 (1.6 ± 0.9) and 5 (1.3 ± 0.7) and severely reduced compared with those seen at stages 4 and 5 in the wild type. Sections of bam1-1 bam2-1 at stages 5 and 6 (data not shown) appeared to be very similar to those of bam1-3 bam2-3. Similar anther sections of bam1-3 bam2-3 plants carrying a ProER-BAM1-FLAG construct (DeYoung et al., 2006) were normal (data not shown).

In summary, bam1 bam2 mutant anthers did not form the normal somatic cells layers in the L2-derived position. The cells that formed in their place were larger, fewer in number, and appeared to be randomly organized; these cells degraded near anther stage 6. Periclinal cell division events in the mutant were reduced compared with the wild type. Although the cells formed by the bam1 bam2 anthers were significantly larger than the normal sporophytic cells, they appeared similar to the PMCs formed in wild-type anthers. We conclude that the bam1 bam2 anther formed pollen mother-like cells (PMLs) in place of the three normal somatic cell types. These PMLs were clearly abnormal, because they degenerated before producing microspores (see below for more characterization).

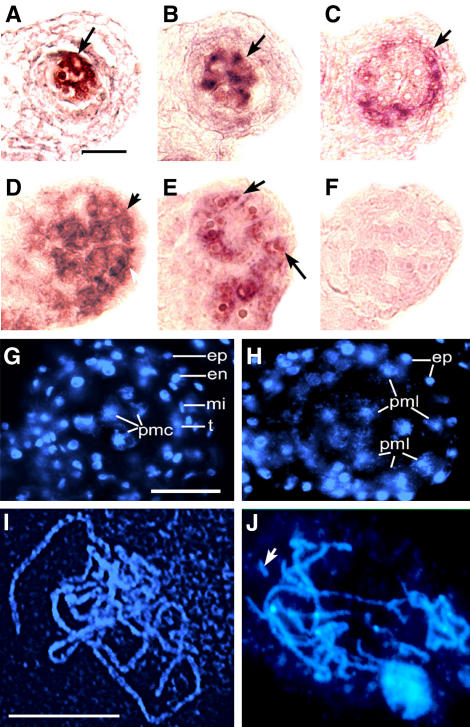

L2-Derived Cells in bam1 bam2 Anthers Express PMC Markers

The L2-derived cells in bam1 bam2 mutant anthers have size, shape, and distribution that are similar to the characteristics of the PMCs, which are normally found interior to the tapetum. To test whether the L2-derived mutant cells have additional properties of PMCs, we examined the expression of known cell identity markers. In wild-type anthers, the meiotic genes ATRAD51 and SDS are strongly expressed in PMCs at stage 6 in the center of each lobe (Figures 4A and 4B, respectively) (Azumi et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004). In stage 6 bam1 bam2 anthers, ATRAD51 and SDS appeared to be expressed (Figures 4D and 4E, respectively) in the L2-derived cells that had not yet degraded, including the cells that occupied a position immediately interior of the epidermis. This finding suggests that the L2-derived PMLs in the bam1 bam2 anther share molecular properties with normal PMCs. To further verify the lack of tapetal cells in the mutant anther, we examined the expression of DYT1, which is very strongly expressed in the wild-type tapetal cells at late anther stage 5 and stage 6 (Figure 4C) (W. Zhang, Y. Sun, and H. Ma, unpublished results). No DYT1 expression was detected in the bam1 bam2 mutant anthers at stages 5 or 6 (Figure 4F; data not shown), indicating the absence of tapetal cells.

Figure 4.

Molecular and Cytological Analyses of Wild-Type and bam1 bam2 Anthers at Stage 6.

(A) to (C), (G), and (I) Wild type.

(D) to (F), (H), and (J) bam1 bam2.

(A) and (D) ATRAD51 was expressed in wild-type PMCs (A) at a high level and in bam1 bam2 (D) interior to the epidermis (arrows).

(B) and (E) SDS was expressed in the wild type (B) at the center of the lobe at the position of the PMCs and in bam1 bam2 (E) in the cells interior and juxtaposed to the epidermis (arrows).

(C) and (F) DYT1 expression. In the wild type (C), DYT1 signal was detected in the tapetal layer, but no detectable DYT1 signal was seen in bam1 bam2 (F).

(G) and (H) Sections of wild-type and bam1 bam2 anthers stained with DAPI.

(G) A wild-type lobe with PMCs undergoing meiosis in the center surrounded by the tapetal layer, middle layer, endothecium, and epidermis.

(H) A bam1 bam2 lobe showing a greater number of PMCs only surrounded by the epidermis and connective tissue.

(I) and (J) DAPI-stained chromosome spreads of wild-type and bam1 bam2 meiotic cells showing pachytene-like chromosomes. Fragments of chromosome can be seen in the bam1 bam2 meiotic cells (J) (arrow) but not in the wild type (I).

en, endothecium; ep, epidermis; mi, middle layer; pmc, pollen mother cells; pml, pollen mother-like cells; t, tapetum. Bar = 20 μm in (A) and (G) and 10 μm in (I). (A) to (F), (G) and (H), and (I) and (J) are of the same magnification.

PMLs in bam1 bam2 Anthers Can Enter but Fail to Complete Meiosis

The ems1 mutant lacks the tapetum layer and produces excess PMCs, which proceed to meiosis II (Zhao et al., 2002). The expression of meiotic genes in bam1 bam2 PMLs suggests that they may also undergo meiosis. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)–stained chromosome spreads. More than 200 cells from mutant anthers were examined. Most cells appeared to be entering or undergoing meiosis, on the basis of their chromosome morphology. Among these, at least one-quarter of them were at the leptotene or zygotene stage of prophase I. In addition, ∼10% of the cells had pachytene-like chromosomes, at midprophase I. Therefore, a substantial fraction of the PMLs had entered meiosis. Amazingly, two of the examined cells were at metaphase I and one was at anaphase I (data not shown). The chromosomes in the metaphase I cells were highly condensed and aligned but appeared to be partially degraded (data not shown). In addition, in the anaphase I cell, the chromosomes segregated unequally between the two poles of the meiocyte. Furthermore, chromosomal fragments were frequently observed at different stages of meiosis (Figure 4J; data not shown). To verify that the cells able to enter meiosis were not confined to the center of the lobes, we performed DAPI staining of sectioned anthers. Whereas in the wild type, the four sporophytic cell layers surrounding the meiotic cells were clearly observable (Figure 4G), in the bam1 bam2 anthers only the epidermis was seen encasing and juxtaposed to a mass of randomly organized PMLs, many of which were evidently undergoing meiosis (Figure 4H).

In summary, the L2-derived cells in bam1 bam2 anthers possessed attributes of PMCs and were partially able to enter meiosis, indicating that the L2-derived cell fates are altered in the mutant anthers. On the other hand, the PMLs exhibited defects at meiotic stages much earlier than the PMCs in the ems1/exs, serk1 serk2, and tpd1 mutants, with most cells unable to complete prophase I before degeneration. Therefore, BAM1 and BAM2 are also important for normal PMC development.

Expression of BAM1 and BAM2 Supports Their Function in Anther Development

To obtain clues about the mechanisms of BAM1 and BAM2 action, we analyzed their expression during early anther development (Figure 5). Overall, BAM1 and BAM2 had very similar expression patterns. Both were expressed in the archesporial cells at anther stage 2 (Figures 5A and 5H) and in the primary parietal and primary sporogenous cells near the lateral edges of stage 3 anthers (Figures 5B and 5I). Interestingly, at stage 4, both genes appeared to be expressed predominantly in the sporogenous cells and might have a low level of expression in the L2-derived secondary parietal cells (Figures 5C and 5J). At stage 5, BAM1 and BAM2 were highly expressed in the PMCs, with a very low level of expression in the tapetum (Figures 5D and 5K). During anther stage 6, both BAM1 and BAM2 were very strongly expressed in the PMCs and tapetum and might be weakly expressed in the middle layer (Figures 5E and 5L). Similarly, at stage 7, strong BAM1 expression was seen in the tapetum and a lower level was seen in the tetrads (Figure 5F). By anther stage 9, there was no detectable BAM1 and BAM2 expression (data not shown). Also, there was no detectable expression in bam1 bam2 double mutant tissues (data not shown). In summary, BAM1 and BAM2 appear to be expressed at stage 2 in the archesporial cells and at stage 3 in the primary sporogenous and primary parietal cells; subsequently, they are preferentially expressed in the sporogenous cells at anther stage 4, after which their expression becomes restricted to the tapetum and PMCs. These expression patterns support an early function that promotes the formation of the primary parietal cells, which are the progenitors of the L2-derived somatic cell layers, and a later function in support of PMC development.

Figure 5.

BAM1 and BAM2 in Situ Hybridization of Wild-Type Ler Anthers.

(A) to (F) BAM1 expression.

(G) Sense control probe.

(H) to (L) BAM2 expression.

(A) and (H) Stage 2 anthers, showing that BAM1 and BAM2 are expressed in lateral L2-derived archesporial cells (arrows).

(B) and (I) Stage 3 anthers; BAM1 and BAM2 are expressed predominantly in the primary sporogenous cells.

(C) and (J) Stage 4 anthers; BAM1 and BAM2 expression is seen predominantly in the sporogenous cells.

(D) and (K) Stage 5 anthers; both genes were highly expressed in PMCs and may have a very low level of expression in the tapetal layer.

(E) and (L) Stage 6 anthers showing that BAM1 and BAM2 are very strongly expressed in the tapetum and PMCs and faintly expressed in the middle layer.

(F) Stage 7 anther showing strong BAM1 expression in the tapetum and somewhat weaker expression in the tetrads.

(G) Sense probe showing no cross-hybridization.

ms, microspores in tetrads; pmc, pollen mother cells; t, tapetal cells. Bar = 20 μm; all panels are of the same magnification.

Possible Relationships of BAM1/2 with SPL and EMS1

As BAM1/2 appear to have a role in promoting the differentiation of the parietal cell type, in situ hybridization experiments were performed with two known anther genes: SPL/NZZ and EMS1/EXS (Figure 6). From anther stages 2 and 4, there was no obvious difference in SPL/NZZ expression between the wild type (Figures 6A and 6B) and bam1 bam2 (Figures 6D and 6E). At stage 5, however, when SPL/NZZ expression was restricted to the PMCs in the wild type (Figure 6C), SPL/NZZ expression in the bam1 bam2 anther had expanded to all or most of the L2-derived cells (Figure 6F), consistent with these cells being similar to PMCs. Conversely, BAM1 expression in the spl mutant appeared normal at stage 2 (cf. Figures 5A and 6G), but in the L2-derived cells, it continued to be restricted to the juxtaepidermal cells at later stages (Figures 6H and 6I). Also, BAM1 expression in the spl mutant appeared to extend into the epidermal cells. This finding is consistent with the failure of the spl mutant to form sporogenous cells and PMCs and suggests that the L2-derived cells may remain undifferentiated or archesporial-like. Therefore, BAM1/2 expression and SPL/NZZ expression at anther stage 2 seem independent of each other; on the other hand, by stage 5, BAM1/2 appear to play a role in restricting SPL/NZZ expression to the PMCs, and SPL/NZZ seems to promote PMC-preferential expression of BAM1.

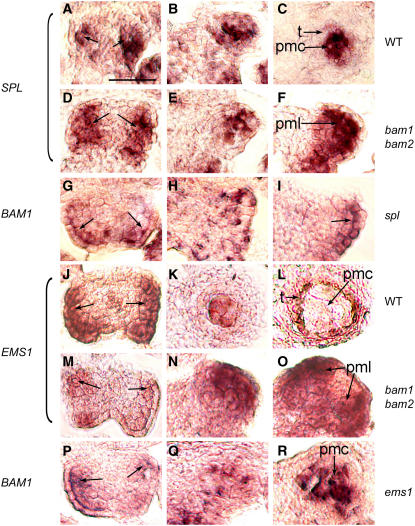

Figure 6.

In Situ Hybridizations of BAM1/2, SPL/NZZ, and EMS1/EXS.

(A) to (C) SPL expression in wild-type anthers.

(D) to (F) SPL expression in bam1 bam2 anthers.

(G) to (I) BAM1 expression in spl anthers.

(J) to (L) EMS1 expression in wild-type anthers.

(M) to (O) EMS1 expression in bam1 bam2 anthers.

(P) to (R) BAM1 expression in ems1 anthers.

(A) and (D) SPL expression in wild-type and bam1 bam2 anthers, respectively, was seen in most of the L2-derived cells at stage 2 (arrows).

(B) and (E) SPL expression in wild-type and bam1 bam2 anthers, respectively, was strongest at the center of each lobe and somewhat fainter in the remaining L2-derived cells at stage 4.

(C) In the wild type at stage 5, strong SPL expression was seen in the PMCs.

(F) In bam1 bam2 at stage 5, strong SPL expression was seen throughout the lobe in the PMLs.

(G) BAM1 expression in the spl anther at stage 2 was seen in the archesporial cells (arrows).

(H) BAM1 expression in the spl anther at stage 4 was confined mainly to the cells immediately adjacent to the epidermis.

(I) BAM1 expression in the spl anther at stage 5 was seen in the epidermis and juxtaepidermal cells at the lateral edges of the lobes (arrow).

(J) EMS1 expression in the wild type at stage 3 was seen in the L2-derived cells and in parts of the epidermis (arrows); this may be broader than what was seen in the bam1 bam2 anther at this stage (M).

(K) EMS1 expression in the wild type at early stage 5 was predominantly in the PMCs and weakly in the tapetum.

(L) EMS1 expression in the wild type at late stage 5/early stage 6 was almost exclusively in the tapetum.

(M) EMS1 expression in the bam1 bam2 anther at stage 3 was in the L2-derived cells (arrows).

(N) and (O) EMS1 expression in the bam1 bam2 anther at early stage 5 and early stage 6, respectively, was seen throughout the anther lobes in PMLs.

(P) BAM1 expression in the ems1 anther at stage 2 was seen in the archesporial cells (arrows).

(Q) BAM1 expression in the ems1 anther at stage 4 was seen predominantly in the center of the lobe and weakly in the other L2-derived cells.

(R) Strong BAM1 expression was seen in the ems1 anther at stage 5 in the PMCs.

pmc, pollen mother cell; pml, pollen mother-like cell; t, tapetum. Bar = 20 μm; all panels are of the same magnification.

For EMS1/EXS expression at early stages, there was no clear difference in the expression pattern between the wild type and bam1 bam2 (Figures 6J and 6M; data not shown). At early wild-type stage 5, EMS1/EXS expression was strong in the PMCs and moderate in the tapetum (Figure 6K). At late stage 5/early stage 6, EMS1/EXS expression was almost exclusively in the tapetum and very weak, if present, in the PMCs (Figure 6L). The bam1 bam2 stage 5 anthers had strong and expanded EMS1/EXS expression in the PMLs (Figure 6N), filling the lobes. Furthermore, strong EMS1/EXS expression continued in the L2-derived cells at stage 6 (Figure 6O), suggesting that the PMLs were different from normal PMCs, in agreement with other studies described above. BAM1 expression in the ems1 mutant was similar to that of the wild type through stage 4 (cf. Figures 5A and 6P). During stages 4 and 5, BAM1 expression was seen in the PMCs of ems1 (Figures 6Q and 6R), consistent with the normal BAM1 expression in PMCs at these stages. Therefore, BAM1/2 may be involved in regulating the reduction of EMS1 expression in the PMCs, but EMS1 does not seem to affect the BAM1 expression pattern.

DISCUSSION

BAM1 and BAM2 Are Important for Normal Cell Division and Differentiation in Early Anther Development

We have demonstrated here that BAM1 and BAM2 together are important for normal early anther development. Our phenotypic studies indicate that bam1 bam2 double mutant anthers have only a slightly reduced number of cells at very early stages, in contrast with the dramatic size reduction of bam1 bam2 meristems (DeYoung et al., 2006). Therefore, the bam1 bam2 anther defects do not seem to be a direct consequence of a greatly reduced anther primordium that resulted from the small mutant meristem. Nevertheless, analysis of subsequent anther stages clearly indicates a dramatic reduction of L2-derived cell numbers, with the bam1 bam2 anther producing fewer than half of the wild-type number of subepidermal cells per lobe, suggesting that cell division is decreased significantly in the mutant. In addition, our analyses showed that the bam1 bam2 mutant failed to specify the normal identity of L2-derived somatic cell layers, completely lacking the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum. Moreover, morphological, cytological, and molecular studies indicate that the L2-derived cells in the mutant had properties of PMCs. Furthermore, BAM1 and BAM2 were expressed in archesporial cells at stage 2, and in the bam1 bam2 double mutant, abnormal cell patterning was visible by stage 3. As BAM1 and BAM2 encode LRR-RLKs, we propose that they meditate a developmental signal that promotes the differentiation of archesporial cells at stage 2 (Figure 7A). Our results strongly support the idea that BAM1 and BAM2 contribute to the differentiation of the parietal and perhaps sporogenous cell types at stage 3. It is possible that BAM1 and BAM2 regulate the asymmetric cell division of the archesporial cells into the primary sporogenous and primary parietal cells.

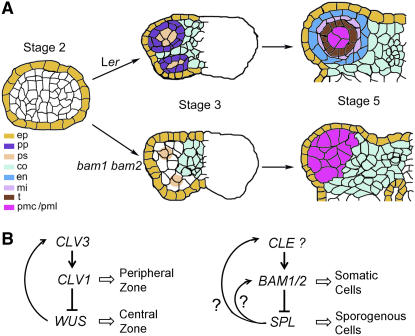

Figure 7.

Model for the Control of Early Anther Cell Differentiation by BAM1 and BAM2.

(A) BAM1/2 function in early anther development. In the wild-type anther by stage 3, archesporial cells have divided to form primary parietal (pp) and primary sporogenous (ps) cells. In the absence of BAM1 and BAM2 function, the asymmetric division of the archesporial cells might be abnormal, resulting in the lack of primary parietal cells and the formation of primary sporogenous-like cells. At anther stage 5, the wild-type anther has three clearly defined concentric cell layers surrounding the pollen mother cells; in the bam1 bam2 anther, however, only PMLs are observed in the area interior of the epidermis. Therefore, BAM1 and BAM2 define a cell–cell signaling pathway critical for the differentiation of the primary parietal and primary sporogenous cells. Abbreviations for cell types are as in Figure 2.

(B) Left, interaction of CLV1, CLV3, and WUS in controlling the stem cell pool in meristems. Right, proposed interaction of BAM1/2, SPL, and a CLE-type gene for a putative ligand for BAM1/2, regulating cell fates in the anther. Arrows indicate positive genetic interactions; lines with a bar at the end denote negative interactions; open arrows represent a positive effect on the cellular process.

In the wild-type anther, the number of somatic cells increases considerably during stages 4 and 5, whereas the sporogenous cells expand in size but do not change dramatically in number during this period. In the bam1 bam2 anther, the decrease in L2-derived cell number is accompanied by the change of somatic cells to PMLs. In the wild type, PMCs are larger than the L2-derived somatic cells; therefore, it is possible that the reduction in number and expansion in size of the mutant L2-derived cells are a reflection of these cells being similar to PMCs. A similar phenomenon was seen in the ems1/exs, tpd1, and serk1 serk2 mutants, which possess a total number of PMCs that is less than the combined number of tapetum and PMCs seen in the wild type but is greater than the number of PMCs seen in the wild type (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2003; Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005). It is possible that when progenitor cells are directed to form PMCs (or PMLs), they divide less frequently and develop into larger cells. An alternative explanation is that in these mutants a negative regulation of PMC proliferation is lacking as a result of the absence of the adjacent somatic cells, allowing the sporogenous cells to proliferate abnormally. Therefore, the functions of BAM1 and BAM2 in regulating cell division and differentiation may be coupled, and the normal functions of these genes are important for the formation of correct cell types in the anther.

BAM1 and BAM2 May Play a Role in Sporogenous Cells

In addition to the BAM1/BAM2 function in very early anther development, strong BAM1 and BAM2 expression was seen from anther stages 4 to 6, preferentially in sporogenous cells and PMCs. This finding suggests possible additional roles for these genes later in anther development. In addition, although the L2-derived cells in the mutant resemble PMCs, they are not normal. Some of the PMLs in the bam1 bam2 mutant were able to initiate meiosis, but none was able to complete meiosis I, and all mutant PMLs eventually degenerated. Sporogenesis requires the coordinated development of multiple adjacent cell types that probably involves cell–cell communication; therefore, it is plausible that BAM1/2 might be needed to receive signaling directed toward the PMCs. It is possible that the bam1 bam2 PMLs did not fully and/or properly differentiate; the strong and expanded EMS1/EXS expression in the bam1 bam2 anther, which persisted through early stage 6, suggests that the PMLs might have some somatic cell properties. Therefore, BAM1 and BAM2 may promote the normal differentiation of PMCs. In addition, BAM1 and BAM2 may be required in the meiocytes for the completion of meiosis. Another possibility is that one or more of the somatic cell layers may be required for meiosis. For example, the tapetum may provide materials and nutrients needed for normal meiosis, or BAM1 and BAM2 may mediate a response to a developmental signal(s) normally released from neighboring cells that promotes the meiotic process. LRR-RLKs constitute a very large gene family, but only a small number of them have been characterized functionally. If BAM1 and BAM2 indeed promote PMC differentiation and/or function, this would be a new function for LRR-RLKs. It is possible that other LRR-RLKs are involved in this complex process, perhaps by interacting with BAM1 and BAM2. Further genetic and molecular studies are needed to uncover and better elucidate LRR-RLK functions in anther development.

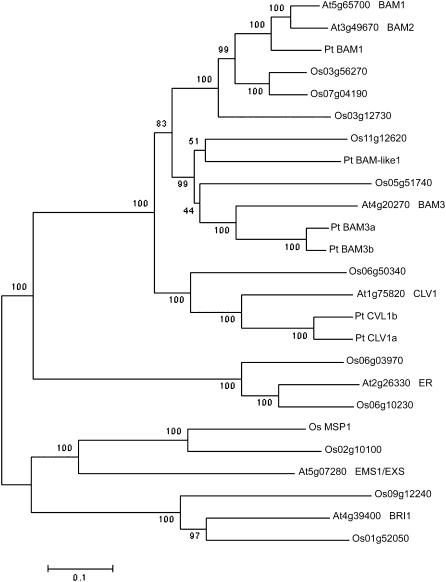

Model for BAM1/2 Function in Anther Development

BAM1 and BAM2 regulate several aspects of development, including meristem size and leaf development (DeYoung et al., 2006). We show here that they are important for the formation of somatic cell types in early anther development. Detailed analysis of the bam1 bam2 anthers suggests that the mutant defect in somatic cell formation is not likely to be a direct consequence of the reduced meristem. Therefore, we believe the BAM1/2 function in anther development is different from that in regulating meristem size. BAM1 and BAM2 are closely related in sequence to CLV1 (DeYoung et al., 2006) (Figure 8), which acts in the meristem (Clark et al., 1996). CLV1 may achieve the correct balance of the central zone and periphery zone in the meristem by limiting cell proliferation in the central zone cells and/or promoting the transition of central zone cells to peripheral zone cells (a form of differentiation) (Clark et al., 1996, 1997; Gallois et al., 2002) (Figure 7B). We found that BAM1 and BAM2 negatively regulate the number of sporogenous cells at the center of the anther lobes, seemingly by promoting the differentiation of the peripheral somatic cells and/or possibly by reducing the division of sporogenous cells. Therefore, the BAM1/BAM2 function in the early anther may be to promote differentiation (and limit proliferation) in a manner analogous to the role of CLV1 in the meristem (Figure 7B). Just as CLV1 acts to restrict the proliferation of the cells in which it is expressed and may promote the differentiation of adjacent cells, BAM1/2 expression and the phenotype conferred by bam1 bam2 suggest that BAM1 and BAM2 may restrict sporogenous cell proliferation while promoting the differentiation of the adjacent parietal cells.

Figure 8.

Neighbor-Joining Tree of Selected Arabidopsis, Rice, and Poplar LRR-RLK Amino Acid Sequences.

Gene identifier numbers starting with At indicate genes from Arabidopsis thaliana; names of genes with functional information are given after the identifier numbers. Gene identifier numbers starting with Os indicate genes from rice (Oryza sativa); MSP1 is also shown as Os MSP1. Pt indicates genes from poplar (Populus trichocarpa), with temporary names given according to sequence similarity to the closest Arabidopsis genes. Bootstrap values are shown near the relevant nodes.

Further support for the functional similarity between BAM1/2 and CLV1 came from transgenic experiments. It was shown that high levels of BAM1 or BAM2 were able to partially rescue the phenotype conferred by clv1-11, and expression of CLV1 using the ER promoter, which is active in the anther, could completely rescue the phenotype conferred by bam1 bam2 (DeYoung et al., 2006). These results suggest that these highly similar proteins have retained some conserved biochemical activities and, when expressed outside of their normal expression domains, are able to interact with components of related signaling pathways (DeYoung et al., 2006). Thus, although CLV1 normally functions to limit meristem stem cell population size and/or to promote the transition of central zone cells to peripheral zone cells, when expressed in the developing anther it can function in the place of BAM1/2 to promote the differentiation of parietal cells and to limit sporogenous cells. CLV3 is thought to encode the ligand for CLV1 and is a member of a conserved gene family in flowering plants called the CLEs (Cock and McCormick, 2001; Carles and Fletcher, 2003); however, clv3 mutants are fertile (Clark et al., 1996), suggesting that either CLV3 is not a ligand for BAM1/2 or that the CLV3 gene is functionally redundant with another gene. Nevertheless, the biochemical similarity of BAM1/2 and CLV1 suggests that the ligand for BAM1/2 may be a member of the CLE family (Cock and McCormick, 2001).

Our results and previous studies strongly support the hypothesis that both SPL/NZZ and BAM1/BAM2 act very early in anther development to promote the formation of several cell types. The spl/nzz mutants do not produce any sporogenous cells, whereas the bam1 bam2 mutant generates an abnormally large number of PMLs, which had several properties of PMCs. Therefore, SPL/NZZ and BAM1/2 seem to act in opposing ways in regulating the number of sporogenous(-like) cells. Furthermore, our results on the expression of these genes suggest that, although the expression patterns of these genes at stage 2 are not affected by each other, BAM1/2 seem to limit the domain of SPL/NZZ expression and SPL/NZZ promotes BAM1 expression in the central sporogenous cells. Therefore, BAM1/2 and SPL/NZZ, as well as the ligand for BAM1/2, may form a regulatory loop (Figure 7B), somewhat similar to the interactions between CLV1, WUS, and CLV3 (Figure 7B) (Carles and Fletcher, 2003). It is likely that wild-type BAM1/2 negatively regulate SPL/NZZ expression indirectly, possibly via the specification of somatic L2-derived cell types, which have reduced SPL/NZZ expression. In addition, the expanded EMS1/EXS expression in the stage 5 bam1 bam2 anther may also reflect a change in cell type, because EMS1/EXS is expressed in the early PMCs. However, normal EMS1/EXS expression is reduced in meiocytes and strong in the tapetum; therefore, the strong EMS1/EXS expression in the bam1 bam2 PMLs at the time of meiosis might be an indication of a defect in meiocyte development in bam1 bam2, supporting a role of the BAM1/2 genes in meiocytes.

BAM1 and BAM2 Function and the Evolution of Sporophytic Cell Types

In the ems1/exs, serk1 serk2, tpd1, and bam1 bam2 mutants, cell differentiation is altered to the end that one or more normal cell layers do not form, but PMCs or PMLs form in their place. These results support the idea that a default pathway leads to the formation of PMCs and that the development of the other cell layers requires differentiation mediated by additional signaling pathways. It is known that nonflowering plants have relatively simple structure in the microsporangium. For example, in leptosporangiate ferns, a series of precise cell divisions results in the formation of the sporangium, which has an outer wall (one cell layer thick), and a two-cell-layered tapetum, which surrounds and provides nutrients to the developing spore mother cells (Raven et al., 1999). Spores are released when the sporophytic sac opens, without the highly decorated wall found on pollen grains. It appears that as vascular plants evolved, particularly angiosperms, they acquired additional developmental pathways that allowed for greater complexity in the structure of the male sporangium, which is the anther lobe in angiosperms. Our results support the hypothesis that through evolution, cell divisions that would have resulted in the formation of sporogenous cells in an ancestor were restricted or otherwise altered to produce other cell types, among which the earliest and most important appears to be the tapetum.

The specification of primary parietal cell fate by the BAM1 and BAM2 LRR-RLKs represents a novel signaling pathway that has implications for the evolution of the sporophytic cell types involved in sporogenesis. The development of PMLs seems to be a default pathway, and the development of the somatic cell types is achieved through the specification of a progenitor cell type (parietal cells) as a result of the acquisition of new signaling pathways, perhaps like that defined by the BAM1 and BAM2 receptors. Distinct homologs of each member of the BAM/CLV1 clade have been identified in poplar (Populus trichocarpa) and rice (Oryza sativa) (Figure 8), suggesting that the function of BAM1 and BAM2 might be conserved in other flowering plants and different from the roles of CLV1 and BAM3. It is known that the homolog of EMS1 in rice, MSP1, has a very similar function to that of EMS1; the rice msp1 mutant also forms excess PMCs in the anther and concomitantly lacks the tapetum (Nonomura et al., 2003). Further investigation of the rice homologs of BAM1 and BAM2 is needed to test whether they also have conserved functions.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Two mutant alleles were found for each of the BAM1 (At5g65700) and BAM2 (At3g49670) genes and were described in detail previously (DeYoung et al., 2006). Briefly, the bam1-1 and bam1-3 alleles were generated in the Columbia ecotype and backcrossed into the Ler ecotype. The bam1-1 allele contains a dSpm insertion and is from the SLAT collection. bam1-3 is a SALK T-DNA line. The bam2-1 and bam2-3 alleles are in the Ler ecotype, and each contains a Ds insertion. bam2-1 is from a launching pad line, and bam2-3 is from the Cold Spring Harbor TRAPPER collection. The two pairs of double mutants used in this study were bam1-1 bam2-1 and bam1-3 bam2-3. Ler plants were used as the wild-type control. Arabidopsis thaliana seeds were planted directly, or transplanted after germinating on Murashige and Skoog plates, on potting mixture and were grown with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 18 to 23°C.

Characterization of the Mutant Phenotype

Scanning electron microscopic analysis was performed on flowers from various stages as described previously (Dievart et al., 2003). Some organs were removed to expose the inner floral organs. Flower buds and inflorescences were prepared for sectioning using a method described previously (Owen and Makaroff, 1995) with some minor modifications (Zhao et al., 2002). Semithin (0.5 μm) sections were made using either a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome or an Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome (both Leica Microsystems) and were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue in 0.1% Na2B4O7 for 30 s. Images were photographed using an Olympus BX51 microscope and a SPOT II RT Slider digital camera with SPOT software version 3.5.8 for Windows (Diagnostic Instruments). Images were edited using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems). Measurement of cell length and height was done using GIMP version 2.2.4 software (http://www.gimp.org). For both the wild type and the mutant, only the cells juxtaposed to the epidermis of stage 5 anther transverse sections were measured. Average cell number and standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

DAPI staining and chromosome spreads were performed as described previously (Ross et al., 1996). DAPI staining of tissue sections was done with young inflorescences that were fixed by methanol:acetone (4:1) fixative for 45 min on ice. They were then embedded in wax and sectioned at 10 μm thick. Dewaxed slides were directly stained with DAPI. Images were taken using a Nikon E800 microscope and a Hamamatsu C4742 digital camera with Image Pro Plus software version 4.5.1.27 for Windows (Media Cybernetics).

In Situ Hybridization Experiments

Nonradioactive RNA in situ hybridization was performed essentially as described (Xu et al., 2002). Young inflorescences of wild type and bam1 bam2 double mutants were fixed in FAA (3.5% formaldehyde, 50% alcohol, and 5% acetic acid) fixative for at least 2 h at room temperature. The tissue was then dehydrated and embedded in Fisher paraffin. Ten-micrometer-thick sections were made using a Shandon Finesse paraffin microtome (Thermo Electron) and were mounted onto slides so that each slide had a similar number of wild-type and bam1 bam2 sections. All slides were dewaxed with Histo-Clear (National Diagnostics), treated with protein kinase for 30 min, and then dehydrated and baked at 42°C for at least 2 h. The dried slides were used immediately or stored at −80°C for up to 6 months. RNA probes labeled with digoxigenin were used for the hybridization. After hybridization, anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase and NBT/BCIP (nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, toluidine salt; Roche Diagnostics) were used to detect any hybridization signal. Images were taken using a BX51 Olympus microscope with a SPOT II RT camera or a Nikon E800 microscope coupled with a Nikon D50 SLR digital camera. All images were then edited using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems).

A fragment of the BAM1 cDNA from 821 to 2250 bp after the ATG initiation codon was amplified using the primers 5′-ATCTAGATCTTCTCCGGTCCATTAACTTGG-3′ and 5′-ACTCGAGTCTGTGTCTTATCCTTCCTAAG-3′ and cloned into the T/A site of the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) (DeYoung et al., 2006). The resulting construct (pMC 3021) was linearized with NotI or SpeI and transcribed using SP6 or T7 to generate the antisense and sense probes, respectively. The BAM2 probes were similarly synthesized using in vitro transcription from a linearized fragment of the BAM2 cDNA, which was amplified with the gene-specific primers 5′-ATCTAGACATTTACAGGGACAATAACTCAA-3′ and 5′-ACTCGAGCTGTGTCTGATTCTACCTAGC-3′ and cloned into pCRII-TOPO, resulting in pMC 3022. The plasmid was linearized with BglII and transcribed using SP6 for the antisense probe. The SDS, EMS1, and ATRAD51 probes were synthesized as described previously (Azumi et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004). The DYT1 probe was synthesized using a cDNA clone (W. Zhang, Y. Sun, and H. Ma, unpublished data). The SPL/NZZ probe was synthesized as described previously (Sieber et al., 2004).

Construction of the Phylogenetic Tree

To generate the phylogenetic tree shown in Figure 8, BAM1, BAM2, BAM3, CLV1, ER, EMS1, and BRI1 protein sequences from Arabidopsis were used to perform a BLASTp search of The Institute for Genomic Research rice (Oryza sativa) pseudomolecules:protein sequences database with no filter. The four members of the BAM/CLV1 clade were also used to search the Populus trichocarpa genomic sequences at the PlantTribes website (http://www.floralgenome.org/cgi-bin/tribedb/tribe.cgi). Redundant sequences were removed. Full-length sequences were imported into ClustalX (Plate-Forme de Bio-Informatique), and a multiple sequence alignment was performed (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA version 3.0 (Kumar et al., 2004) (http://www.megasoftware.net/index.html) and the neighbor-joining algorithm as well as a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates to test the significance of the nodes. Default parameters were used, including random seed initiation, the amino:Poisson correction model, and uniform rates among sites, and gaps were deleted.

Accession Numbers

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifiers for the genes mentioned in this article are At5g65700 (BAM1) and At3g49670 (BAM2).

Supplemental Data

The following material is available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Multiple Sequence Alignment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bridget Leyland for help in collecting our quantitative data and with plant care and Khushboo Nangia, Sarah Suchy, and Gavilange Nestor for help in plant care and sectioning. We also thank Steven Hord for assistance in collecting data, editing, and preparing images. We thank Kay Schneitz and Patrick Sieber for the SPL/NZZ template, Wei Zhang for the DYT1 template, and Wei Hu for help in phylogenetic analysis. We also thank Julian Schroeder and Sacco de Vries for communicating results before publication. This work was supported by grants from the Department of Energy (DE-FG02-02ER15332) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM-63871-01) to H.M., by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM-62962-05 to S.E.C., and by funds from the Department of Biology and the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at Pennsylvania State University. This research used plant materials generated with support from National Science Foundation Grant 0215923. C.L.H.H. was partially supported by the Integrative Bioscience Graduate Degree Program at the Pennsylvania State University. B.J.D. was partially supported by the Cellular Biotechnology training program.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) are: Steven E. Clark (clarks@umich.edu) and Hong Ma (hxm16@psu.edu).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.105.036871.

References

- Albrecht, C., Russinova, E., Hecht, V., Baaijens, E., and de Vries, S. (2005). The Arabidopsis thaliana SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASES1 and 2 control male sporogenesis. Plant Cell 17 3337–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azumi, Y., Liu, D., Zhao, D., Li, W., Wang, G., Hu, Y., and Ma, H. (2002). Homolog interaction during meiotic prophase I in Arabidopsis requires the SOLO DANCERS gene encoding a novel cyclin-like protein. EMBO J. 21 3081–3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, F., Haseloff, J., Schiefelbein, J., and Dolan, L. (1998). Positional information in root epidermis is defined during embryogenesis and acts in domains with strict boundaries. Curr. Biol. 8 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, D.C. (2004). Integrating signals in stomatal development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales, C., Bhatt, A.M., Scott, R., and Dickinson, H. (2002). EXS, a putative LRR receptor kinase, regulates male germline cell number and tapetal identity and promotes seed development in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 12 1718–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles, C.C., and Fletcher, J.C. (2003). Shoot apical meristem maintenance: The art of a dynamic balance. Trends Plant Sci. 8 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.E., Jacobsen, S.E., Levin, J.Z., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1996). The CLAVATA and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS loci competitively regulate meristem activity in Arabidopsis. Development 122 1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.E., Williams, R.W., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1997). The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell 89 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock, J.M., and McCormick, S. (2001). A large family of genes that share homology with CLAVATA3. Plant Physiol. 126 939–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet, J., Boisson-Dernier, A., Ros-Palau, R., Vera, C.E., and Schroeder, J.I. (2005). Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASES1 and 2 are essential for tapetum development and microspore maturation. Plant Cell 17 3350–3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, M., Delourme, R., Gourret, J.P., Mariani, C., and Renard, M. (1993). Expression of engineered nuclear male sterility in Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. 101 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, B.J., Bickle, K.L., Schrage, K.J., Muskett, P., Patel, K., and Clark, S.E. (2006). The CLAVATA1-related BAM1, BAM2 and BAM3 receptor kinase-like proteins are required for meristem function in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 45 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dievart, A., Dalal, M., Tax, F.E., Lacey, A.D., Huttly, A., Li, J., and Clark, S.E. (2003). CLAVATA1 dominant-negative alleles reveal functional overlap between multiple receptor kinases that regulate meristem and organ development. Plant Cell 15 1198–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J.C., Brand, U., Running, M.P., Simon, R., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1999). Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283 1911–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallois, J.L., Woodward, C., Reddy, G.V., and Sablowski, R. (2002). Combined SHOOT MERISTEMLESS and WUSCHEL trigger ectopic organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Development 129 3207–3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, R.B., Beals, T.P., and Sanders, P.M. (1993). Anther development: Basic principles and practical applications. Plant Cell 5 1217–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake, S., and Freeling, M. (1986). Analysis of genetic mosaics shows that the extra epidermal cell divisions in Knotted mutant maize plants are induced by adjacent mesophyll cells. Nature 320 621–623. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z., Wang, Z.Y., Li, J., Zhu, Q., Lamb, C., Ronald, P., and Chory, J. (2000). Perception of brassinosteroids by the extracellular domain of the receptor kinase BRI1. Science 288 2360–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, V., Vielle-Calzada, J.P., Hartog, M.V., Schmidt, E.D., Boutilier, K., Grossniklaus, U., and de Vries, S.C. (2001). The Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE 1 gene is expressed in developing ovules and embryos and enhances embryogenic competence in culture. Plant Physiol. 127 803–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord, C.L.H., and Ma, H. (2006). Genetic control of anther cell division and differentiation In Cell Division Control in Plants, D.P.S. Verma and Z. Hong, eds (Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag), in press.

- Ito, T., Wellmer, F., Yu, H., Das, P., Ito, N., Alves-Ferreira, M., Riechmann, J.L., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (2004). The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls microsporogenesis by regulation of SPOROCYTELESS. Nature 430 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, C.A., and Crane, M.B. (1927). Formation and morphology of Solanum chimeras. J. Genet. 18 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Tamura, K., and Nei, M. (2004). MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, S.H., Shen, R., and Schiefelbein, J. (2005). Positional signaling mediated by a receptor-like kinase in Arabidopsis. Science 307 1111–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, M., and Laux, T. (2003). Stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem is regulated by intercellular movement of CLAVATA3 and its sequestration by CLAVATA1. Development 130 3163–3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Wen, J., Lease, K.A., Doke, J.T., Tax, F.E., and Walker, J.C. (2002). BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Chen, C., Markmann-Mulisch, U., Timofejeva, L., Schmelzer, E., Ma, H., and Reiss, B. (2004). The Arabidopsis AtRAD51 gene is dispensable for vegetative development but required for meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 10596–10601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. (2005). Molecular genetic analyses of microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56 393–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, C., De Beuckeleer, M., Truettner, J., Leemans, J., and Goldberg, R.B. (1990). Induction of male sterility in plants by a chimaeric ribonuclease gene. Nature 347 737–741. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, C., Goldberg, R.B., and Leemans, J. (1991). Engineered male sterility in plants. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 45 271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam, K.H., and Li, J. (2002). BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell 110 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura, K., Miyoshi, K., Eiguchi, M., Suzuki, T., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H., and Kurata, N. (2003). The MSP1 gene is necessary to restrict the number of cells entering into male and female sporogenesis and to initiate anther wall formation in rice. Plant Cell 15 1728–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, H.A., and Makaroff, C.A. (1995). Ultrastructure of microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. ecotype Wassilewskija (Brassicaciae). Protoplasma 185 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, P.H., Evert, R.F., and Eichhorn, S.E. (1999). Biology of Plants, 6th ed. (New York: Worth Publishers), pp. 453–454.

- Rojo, E., Sharma, V.K., Kovaleva, V., Raikhel, N.V., and Fletcher, J.C. (2002). CLV3 is localized to the extracellular space, where it activates the Arabidopsis CLAVATA stem cell signaling pathway. Plant Cell 14 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, K.J., Fransz, P., and Jones, G.H. (1996). A light microscope atlas of meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Chromosome Res. 4 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, P.M., Bui, A.Q., Weterings, K., McIntire, K.N., Hsu, Y., Lee, P.Y., Truong, M.T., Beals, T.P., and Goldberg, R.B. (1999). Anther development defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11 297–322. [Google Scholar]

- Scheres, B., and Benfey, P.N. (1999). Asymmetric cell division in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50 505–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefthaler, U., Balasubramanian, S., Sieber, P., Chevalier, D., Wisman, E., and Schneitz, K. (1999). Molecular analysis of NOZZLE, a gene involved in pattern formation and early sporogenesis during sex organ development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 11664–11669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, E.D., Guzzo, F., Toonen, M.A., and de Vries, S.C. (1997). A leucine-rich repeat containing receptor-like kinase marks somatic plant cells competent to form embryos. Development 124 2049–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, S.H., and Bleecker, A.B. (2001). Receptor-like kinases from Arabidopsis form a monophyletic gene family related to animal receptor kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 10763–10768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, S.H., and Bleecker, A.B. (2003). Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132 530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak, E.D., McAbee, J.M., Pillitteri, L.J., and Torii, K.U. (2005). Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science 309 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber, P., Petrascheck, M., Barberis, A., and Schneitz, K. (2004). Organ polarity in Arabidopsis. NOZZLE physically interacts with members of the YABBY family. Plant Physiol. 135 2172–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, D.R., Bowman, J.L., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (1990). Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2 755–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.N., and Dermen, H. (1975). Flexibility in ontogeny as shown by the contribution of the shoot apical layers to leaves of periclinal chimeras. Am. J. Bot. 62 935–947. [Google Scholar]

- Szymkowiak, E.J., and Sussex, I.M. (1996). What chimeras can tell us about plant development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47 351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, C., Willemsen, V., Hage, W., Weisbeek, P., and Scheres, B. (1995). Cell fate in the Arabidopsis root meristem determined by directional signalling. Nature 378 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y., Seto, H., Fujioka, S., Yoshida, S., and Chory, J. (2001). BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature 410 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.Y., Chong, K., Xu, Z.H., and Tan, K.H. (2002). Practical techniques of in situ hybridization with RNA probe. Chin. Bull. Bot. 19 234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.L., Jiang, L.X., Puah, C.S., Xie, L.F., Zhang, X.Q., Chen, L.Q., Yang, W.C., and Ye, D. (2005). Overexpression of TAPETUM DETERMINANT1 alters the cell fates in the Arabidopsis carpel and tapetum via genetic interaction with EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1/EXTRA SPOROGENOUS CELLS. Plant Physiol. 139 186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.L., Xie, L.F., Mao, H.Z., Puah, C.S., Yang, W.C., Jiang, L., Sundaresan, V., and Ye, D. (2003). TAPETUM DETERMINANT1 is required for cell specialization in the Arabidopsis anther. Plant Cell 15 2792–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.C., Ye, D., Xu, J., and Sundaresan, V. (1999). The SPOROCYTELESS gene of Arabidopsis is required for initiation of sporogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear protein. Genes Dev. 13 2108–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.Z., Wang, G.F., Speal, B., and Ma, H. (2002). The EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1 gene encodes a putative leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase that controls somatic and reproductive cell fates in the Arabidopsis anther. Genes Dev. 16 2021–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.