Abstract

Murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) and human CMV (HCMV) share many features making the mouse system a potential small-animal model for HCMV. Although the genomic DNA sequence and the predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of MCMV have been determined, experimental evidence that the ORFs are actually transcribed has been lacking. We developed an MCMV global-DNA microarray that includes all previously predicted ORFs and 14 potential ones. A total of 172 ORFs were confirmed to be transcribed, including 7 newly discovered ORFs not previously predicted. No gene products from 10 previously predicted ORFs were detected by either DNA microarray analysis or reverse transcriptase PCR in MCMV-infected mouse fibroblasts, although 2 of those were expressed in a macrophage cell line, suggesting that potential gene products from these open reading fames are silenced in fibroblasts and required in macrophages. Immunohistochemical localization of the six newly described ORF products and three recently identified ones in cells transfected with the respective construct revealed four of the products in the nucleus and five in mitochondria. Analysis of two ORFs using site-directed mutagenesis showed that deletion of one of the mitochondrion-localized gene products led to significantly decreased replication in fibroblasts.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the most ubiquitous agent of infection in people of any age (28, 34), infecting 50 to 90% of the population (16). It is also the most common infectious agent in blood transfusion. HCMV infection causes serious disease in immunocompromised individuals, including AIDS patients, organ transplant patients, and newborns (21, 34). HCMV is a leading cause of birth defects and represents a significant economic burden to the U.S. health care system (2). It is not only the leading nongenetic cause of neurosensory hearing loss (29, 34) but also a major cause of organ transplant failure (32). Moreover, HCMV has been reported to activate human immunodeficiency virus replication (4). Therapies for CMV infection disease are still unsuccessful largely because the interaction between CMV and host cells is poorly understood.

The highly restricted species specificity of cytomegaloviruses has limited HCMV studies with animal models and hampered the studies of HCMV replication and pathogenesis. Remarkably, the effects of murine CMV (MCMV) infection in mice resemble those of HCMV in humans with respect to pathogenesis during acute infection, persistent infection, and reactivation from latency after transfusion, transplantation, and immunosuppression (34). In addition, both viruses share the same sequential gene expression sequence defined as the immediate early (IE), early (E), and late (L) stages, and both have in vivo tropism for hematopoietic tissue and secretory glands and induce the same immune responses in their respective hosts. The similarities of the two viruses in their biological, genetic, and pathogenic properties have allowed the use of MCMV infection in mice as a model system to study HCMV infection.

The genome size of both HCMV and MCMV is about 230 kb of DNA. It has been more than 10 years since the publication of the genomic DNA sequences for HCMV (9, 10) and MCMV (19, 30). During this time, the HCMV genome organization (12, 24) has been revised, reevaluated, and corrected for different strains (25, 26). The annotated open reading frames (ORFs) of laboratory strains, including AD169 and Towne, have been further modified. The most recent annotation (25, 26) has taken comparisons with other cytomegaloviruses into consideration. In contrast, MCMV genomic studies have not been pursued except in one recent report that predicts additional potential ORFs from the previously published DNA sequence (8, 30). Another recent study identified two ORFs, designated m166.5 and ORF105932-106072, by sequencing the proteins isolated from MCMV virions (19). These studies point to the likelihood of additional ORFs that have not been recognized by their actual transcripts or that have not been predicted previously. Even ORFs previously predicted from sequence data must be verified as transcribed experimentally, since only then is it likely that the ORFs are actually expressed.

The need for a detailed gene expression profile for MCMV assumes special importance in light of the potential usefulness of this virus as a gene therapy transmission vector and in vaccine development. MCMV uses ubiquitous cell surface heparin sulfate proteoglycans and integrin molecules to enter cells, enabling entry into cells of nonhost species (11, 13, 20, 36-38, 42). MCMV infection in nonhost cells can proceed to the DNA replication stage so that the gene products essential for DNA replication are clearly produced. Strong species specificity and cell and tissue tropism similar to that of HCMV suggest MCMV as a potential vector for transgene transmission into human cells (33, 41). With the help of HCMV IE1, MCMV can express more genes and even produce viral particles (35a), suggesting that recombinant MCMV grown in human cells expressing certain HCMV genes would improve the efficiency of an MCMV vector. MCMV-based vectors appear to be safe since no viral particles form in human cells and no interference with human immune functions has been observed (33). Moreover, such vectors efficiently produce any protein due to strong activation of some of their promoters in human cells.

Our study to identify additional MCMV ORFs is based on the published MCMV sequence and ORF predictions. We used both MacVector and GenePicker software to retrieve additional potential ORFs and designed an MCMV DNA microarray assay. With this system we eliminated eight previously suggested open reading frames as potentially expressed genes and added seven newly described ones expressed in fibroblasts. An additional two genes were expressed only in macrophages but were repressed in fibroblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture and virus.

NIH 3T3 cells (from the ATCC) and the macrophage cell line IC21 (provided by Ann Campbell) (17) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For immunohistochemical staining, cells were grown on round coverslips (Corning Glass Inc., Corning, NY) in 24-well plates (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware, Lincoln Park, NJ). The MCMV Smith strain was obtained from the ATCC.

Plaque formation unit assay.

Viral titers were determined by plaque assay as described previously (35) with slight modification. Supernatants containing serial dilutions of virus particles were added to confluent NIH 3T3 cell monolayers in a six-well plate. After absorption for 2 h, the medium was removed and cells were washed twice with serum-free DMEM and overlaid with phenol-free DMEM containing 5% fetal calf serum, 0.5% low-melting-point agarose (GIBCO), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Numbers of PFU were determined after averaging from different dilutions.

Antibodies and plasmids.

Monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody M2 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO), rabbit antibody to HDAC2 was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), and serum containing autoantibodies that recognize mitochondria was from a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis (14). Plasmids used in this study include pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); pSM3 and pKD46 (43), gifts from M. Messerle (23); and pCMV-zeo, from H. Zhu (27).

MCMV oligonucleotides for MCMV gene microarrays.

MCMV ORF analysis was based on the published DNA sequence (30). The MacVector program was used to search both strands of the MCMV genome for all ORFs greater than or equal to 50 amino acids. A BLAST search against the Swiss-Prot and nonredundant databases was performed to identify ORFs which have previously been characterized in the original annotation of the MCMV genome (30). Mapping of the previously identified ORFs as well as novel ORFS revealed 14 previously unidentified ORFs of interest due to their genomic location. Candidate probe targets for an oligonucleotide-based array were selected by using the OligoPicker program (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/oligopicker/). Each viral target 60-mer oligonucleotide was screened for cross-reactivity and cellular transcript hybridization against the nonredundant sequence cluster for murine coding regions (http://genetics.mgh.harvard.edu/xwang/dataset/uni_mouse_cds.fasta) as well as cross-reactivity with the other viral ORFs. Additionally, two murine cellular transcripts were added for normalization. One hundred eighty-four amino-6C (6-carbon chain)-modified 60-mer oligonucleotides were synthesized by QIAGEN Inc. (Valencia, CA) (see the supplemental material) and resuspended in 1× printing buffer (150 mM sodium phosphate, 0.0005% sarcosyl) to a final concentration of 20 μM. Slides were printed at the Microarray Facility of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) using a GeneMachines (San Carlos, CA) OmniGrid microarrayer and were printed in six identical subarrrays on Amersham (San Francisco, CA) Codelink activated slides. Slides were treated according to the protocol established by the Microarray Core at Massachusetts General Hospital (https://dnacore.mgh.harvard.edu/microarray/protocol-printing.shtml).

Briefly, printed slides were incubated overnight at room temperature in a NaCl saturated humid environment. Slides were then blocked in 1× blocking solution (50 mM 2-aminoethanol, 0.1 M Tris, 0.1% N-lauroyl sarcosine, pH 9), for 15 min at 55°C. Slides were rinsed twice in H2O and then incubated in 1× washing solution (4× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.11% N-lauroyl sarcosine) for 30 min at 55°C, followed by two rinses in H2O. Slides were dried by centrifugation (800 rpm for 5 min) and then stored in a desiccator until hybridized. Three randomly chosen slides of each print run were examined to ensure that the oligonucleotides were printed at uniform levels.

Microarray analysis.

Total RNAs were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). First-strand cDNA was reverse transcribed, purified, and labeled with Cy-3 UTP using the SuperScript indirect cDNA labeling system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNAs were hybridized with the oligonucleotide arrays printed on the slides as described above. Hybridization and washing were performed using the TECAN HS4800 hybridization station (TECAN Austria GmbH, Grödig, Austria) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Slides were scanned with the microarray-equipped GenePix Pro600 microarray scanner (Union City, CA), and data were analyzed using GenePix software (Union City, CA). The experiments were performed twice independently. In each of the experiments, two hybridizations were conducted. Each slide contains six arrays of all viral potential genes. Since transcription signals appeared reproducibly, we selected the one shown in Fig. 1. We also averaged the signal units (si); negative ones like those for water controls are between 300 and 400 si. We used 500 si as the cutoff; signals of clearly positive spots are above 500 si. The cDNAs used for this DNA microarray were not amplified, so results are highly specific but not sensitive enough. Therefore, we performed RT-PCR to confirm those whose signals are less than 500 si.

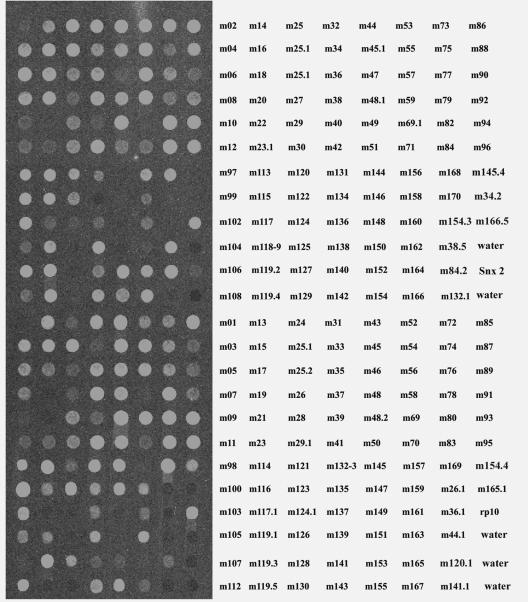

FIG. 1.

Gene array of MCMV gene expression in NIH 3T3 cells. Total RNAs from MCMV-infected NIH 3T3 cells were isolated at 24 h p.i., and first-strand cDNA was made and purified using the SuperScript indirect cDNA labeling system (Invitrogen). The cDNAs were hybridized with the oligonucleotide arrays printed on Codelink glass slides. Slides were processed with a microarray scanner (i.e., the Axon GenePix 4000a scanner or a like product), and data were analyzed by GenePix software. The names of ORFs are shown on the right side, which corresponds to the location of the spotted oligonucleotides of the microarrays on the left side. “Water” indicates that the wells are free from DNA oligonucleotides. rp10, ribosomal protein 10, accession no. BG085976; Snx2, sorting nexin 2, accession no. BG086506.

Molecular cloning.

Plasmid pcDNA3 cut with EcoRI and HindIII was used as a vector. PCR fragments of the newly found potential gene cDNA were generated by adding EcoRI and HindIII at each end. The following primers were used: m166.5 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAT CAC CCT GCT CAG-3′) and m166.5 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CGA GCG CGG GGC GGC TGA-3′); m154.3 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG ACT ACG ATT GTC AGG-3′) and m154.3 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC GTA GCG TCG AGA GAT ACC-3′); m145.4 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG ATA ACG CAA AAC AAC-3′) and m145.4 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC GAG TCT GCC CCT ACA TCT-3′); m132.1 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG TCT GAT GTG CAA GGA-3′) and m132.1 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC TAT CCA GCC TGA AAG ACA-3′); m120.1 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GGG CGT GCT CGC AGC-3′) and m120.1 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CAA CTC GGT GAT CTC GGC-3′); m84.2 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG TCA GGA GAT CCT CGG-3′) and m84.2 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CCC TCT ATC CCT CTC TCC-3′); m38.5 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAG AGT GTG CGC CGA-3′) and m38.5 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC GAA TGT GTA ATC TCC ATC-3′); m34.2 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAT GGG TTA AAT AAT-3′) and m34.2 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC CCG AAC GAG ATA AAC GGA-3′); and m154.4 For (5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG CGA CGA CGG GAT GGA-3′) and m154.4 Rev (5′-GCT GAA TTC CTA CTT GTC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC AAA AAA CAT CGA GTT AAA-3′).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA from cells were isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNA was further cleared using DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using the Superscript reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Table 1 lists the primers used for reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR).

TABLE 1.

Summary of MCMV gene expression in NIH 3T3 cells and the IC21 cell line from weak and negative signals by microarray analysis and RT-PCR

| ORF | Microarray result with NIH 3T3 cells | RT-PCR result witha:

|

Primers for RT-PCR

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH 3T3 cells | Macrophages | Forward | Reverse | ||

| m01 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG AAG AGA ATC GGG TTG-3′ | 5′-TCA GCC TCC GGG CCG CGC G-3′ |

| m19 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG AGT ATC ATC GCC ACA-3′ | 5′-TCA CCC TCG CCG TGA TCG CC-3′ |

| m21 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG ACA GGT ATC CGA TAC-3′ | 5′-TTA AAT CGA TAC CAT CTG CC-3′ |

| m22 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG CGG GCG GGC GGG CAG-3′ | 5′-TTA CAC TCC AGG GCG ACC-3′ |

| m26.1 | Weak | 5′-ATG GAG ATC GCA CGA-3′ | 5′-TCA TTT TTC CAG AGT-3′ | ||

| m26 | Negative | − | + | 5′-ATG GGT GGC GAA TGC CTG AG-3′ | 5′-TCA CAT GTG GGA CAG AGC C-3′ |

| m34.2 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAT GGG TTA AAT AAT-3′ | 5′-CCG AAC GAG ATA AAC GGA-3′ |

| m36.1 | Negative | + | ND | 5′-ATG CAT CCA TCC ATC CAT-3′ | 5′-TTC TTT CGG GAA AGG GGT-3′ |

| m38.5 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAG AGT GTG CGC CGA-3′ | 5′-GAA TGT GTA ATC TCC ATC-3′ |

| m44.1 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG CAG ACC TTG GCG CTG-3′ | 5′-ATC TCC GCG GGA ATG GAG-3′ |

| m58 | Weak | − | − | 5′-ATG ACG ACG GGG GTC GCC TTG-3′ | 5′-CTA CGA GAC CAC AAA TCG GT-3′ |

| m69.1 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG AGC ATT TCG TTT CCA G-3′ | 5′-TCA TCG ACC CTT CCC CTC C-3′ |

| m70 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-ATG ACC GTC GTG CTG TTC GC-3′ | 5′-GGT GTT GTT GAG ATA GCG TA-3′ |

| m84.2 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG TCA GGA GAT CCT CGG-3′ | 5′-CCC TCT ATC CCT CTC TCC-3′ |

| m107 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG GAC GGA CGG ACG GGC-3′ | 5′-TCA ACC TAG TGG CGC TCC T-3′ |

| m117.1 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG TCC GAG ACG TCG GTA TG-3′ | 5′-GCA GCC GAC GGA CGC TAG-3′ |

| m119.5 | Negative | + | ND | 5′-ATG ATC GCG ACG GCG ACG-3′ | 5′-TCA TCC TAC TGG CCG CGT TAG-3′ |

| m120.1 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GGG CGT GCT CGC AGC-3′ | 5′-CAA CTC GGT GAT CTC GGC-3′ |

| m124.1 | Weak | − | − | 5′-ATG GTG GCC TCC TTC TCC-3′ | 5′-TCA GGA CGG GGC AAG AGA G-3′ |

| m125 | Weak | − | + | 5′-ATG TAC TGG GCA AAA CCC-3′ | 5′-TCA ATG TGG GTG AGT CAA TAG-3′ |

| m126 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG GCT ACC GCG GTT TTC G-3′ | 5′-CTA AGG CAC ATA CCC CGG-3′ |

| m127 | Negative | + | ND | 5′-ATG GAG AAC AAG AGA GAT C-3′ | 5′-TTA TAA TGA CCC AGG GGA A-3′ |

| m129 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG ATG TAC GTG GCC GAT G-3′ | 5′-TTA TTC ATC GGA CAG TCG TTG-3′ |

| m130 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG CGT GGC GAT TCC GTC-3′ | 5′-TCA TCT GAA ATG GGA ACG-3′ |

| m132.1 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG TCT GAT GTG CAA GGA-3′ | 5′-TAT CCA GCC TGA AAG ACA-3′ |

| m134 | Negative | + | ND | 5′-ATG GCA GTC GAC GTC ACG-3′ | 5′-TCA TTG TCG GAC AGA ACA G-3′ |

| m141.1 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG ATA ATG CCG CTG GTG-3′ | 5′-TGG TGA CCA ACG CGG ACA-3′ |

| m144 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG AGG GCT CTG GCG CTG-3′ | 5′-CCT CGG TTT CGT TGC CGT-3′ |

| m145.4 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG ATA ACG CAA AAC AAC-3′ | 5′-GAG TCT GCC CCT ACA TCT-3′ |

| m148 | Weak | − | − | 5′-ATG CAC GGT CAA CAC GCC-3′ | 5′-CTA TAT GTT AAT TTT CAC-3′ |

| m149 | Negative | − | + | 5′-ATG ACC GTC TCG TTC TTC-3′ | 5′-TTA AAC GAT TTC ACG ACC TC-3′ |

| m150 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG TGT ATT GTC GCG GTT C-3′ | 5′-GAA CAG CCG CGC TTT GAC CG-3′ |

| m151 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG ATT GGC GTG ATA CGT G-3′ | 5′-ATT CAC AAG ACT CGT TAT TCC-3′ |

| m154.3 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG ACT ACG ATT GTC AGG-3′ | 5′-GTA GCG TCG AGA GAT ACC-3′ |

| m154.4 | Very weak | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG CGA CGA CGG GAT GGA-3′ | 5′-AAA AAA CAT CGA GTT AAA-3′ |

| m157 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG GTC ATC GTC CCC CTA G-3′ | 5′-GAA TAT TAA TCT TAC CAG TCT-3′ |

| m165 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG GCC CTC GGG CCT ACG-3′ | 5′-GAG AAA AGT CAG AAC CGC GA |

| m165.1 | Negative | − | − | 5′-ATG ACG GCC GGT GGC CGC-3′ | 5′-CGT GGT TCG TGG CGG GAC-3′ |

| m166.5 | Positive | + | ND | 5′-TCG AAG CTT ATG GAT CAC CCT GCT CAG-3′ | 5′-CGA GCG CGG GGC GGC TGA-3′ |

| m170 | Weak | + | ND | 5′-ATG TGC TCG GTT AAC GAG TTG-3′ | 5′-TTA CCT GGT ACC TGC GCG GCG-3′ |

+, positive; −, negative; ND, not detected.

Immunohistochemistry.

Cells seeded on coverslips were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 on ice for 20 min. Primary antibody was added for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS before the addition of secondary antibody labeled with Texas Red or fluorescein isothiocyanate (green) of either anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G for another 30 min at room temperature. After being washed with PBS, cells were stained with Hoechst 33258.

Generation of m34.2 and m120.1 deletion mutants and their revertant viruses.

Escherichia coli DH10B (ATCC) containing the MCMV bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) pSM3 (chloramphenicol resistance), a gift from M. Messerle (23), was transformed with plasmid pKD46 (43), which produces red recombinase upon induction with 10 mM l-arabinose. The transformant was washed in sterile water to make competent cells for electroporation. PCR fragments containing 40-bp homologues on either side of and within m120.1 or m34.2 and flanking the zeocin resistance marker were made using pCMV-zeo (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (27) as the template and the following specific primers: del120.1 forward (5′-CTT CGT TTT CGA AGA GCC CAT GTC TTT CAT CCC CGT CGT GGG AAC GGT GCA TTG GAA CGG AC-3′), del120.1 reverse (5′-GCG TGC TCG CAG CCT CCT GTG CTT CGC CGT GAT CTT GTG CCA AGT TTC GAG GTC GAG TGT CAG-3′), del34.2 forward (5′-GCT CTA AGG GGG GCG CGG GAC GAG GGG AAC GGT CGA GAC AGG AAC GGT GCA TTG GAA CGG AC-3′), and del34.2 reverse (5′-CGT ACC GAG ATG TTT TTA TTA GAT GTA AAC ACA CAC ACG ACA AGT TTC GAG GTC GAG TGT CAG-3′). PCR fragments were transformed into competent E. coli cells by electroporation. Specific-gene-deleted BAC MCMVs selected based on chloramphenicol and zeocin resistance were transfected into NIH 3T3 cells to generate the MCMV mutants MCMVdl120.1 and MCMVdl34.2.

To rescue the mutants, the mutant BAC DNA, MCMVdl120.1 or MCMVdl34.2, and the full-length respective cDNA were cotransformed into E. coli that harbors pKD46 producing red recombinase. Revertant BAC DNAs were identified by PCR. Revertant MCMVs were made by transfection of the revertant BAC DNAs into NIH 3T3 cells, resulting in MCMVRQ120.1 and MCMVRQ34.2.

Confocal microscopy.

Cells were examined with a Leica TCS SPII confocal laser scanning system. Two channels were recorded simultaneously and/or sequentially and controlled for possible wavelength overlap between the green and red channels. Single-antibody-labeled control cells were used to test for and suppress any breakthrough. The images were then arrayed for presentation using Photoshop.

RESULTS

DNA microarray assay of MCMV in NIH 3T3 cells.

The previously annotated DNA sequence of MCMV ORFs predicts 170 ORFs (30) from both strands of DNA. To test whether all of the predicted ORFs are actually expressed and whether there are more ORFs than previously predicted, we reanalyzed the MCMV DNA sequence using a DNA analysis program (MacVector) and found 14 additional ORFs of interest. They were selected so as not to significantly overlap with any other previously predicted ORFs. We designed 184 oligonucleotides, 60 nucleotides in size (see the supplemental data), to produce the microarray assay system for MCMV cDNAs. Total RNA was extracted from MCMV-infected NIH 3T3 cells at 6, 24, and 48 h postinfection (p.i.) using 1 PFU per cell. At the time and with the number of PFU chosen for inclusion of data here, cells demonstrated a variety of stages in the infection cycle, including infection of new cells, when assayed by immunofluorescence with antibodies that detect viral proteins produced at different stages. Thus, immediate early, early, and late genes should be transcribed. To ensure specificity, the cDNA was not amplified. The results are shown in Fig. 1 for a single set. Each slide had six identical subarrays; the hybridizations for them were simultaneously scanned, and an average hybridization was determined. Based on comparison with background in the water control slots, 154 ORFs provided a positive signal (Fig. 2). Of those positive, 145 were confirmations of previous predictions. Thus, the MCMV DNA microarray detected 154/184 (84%) of the predicted ORFs as being transcribed.

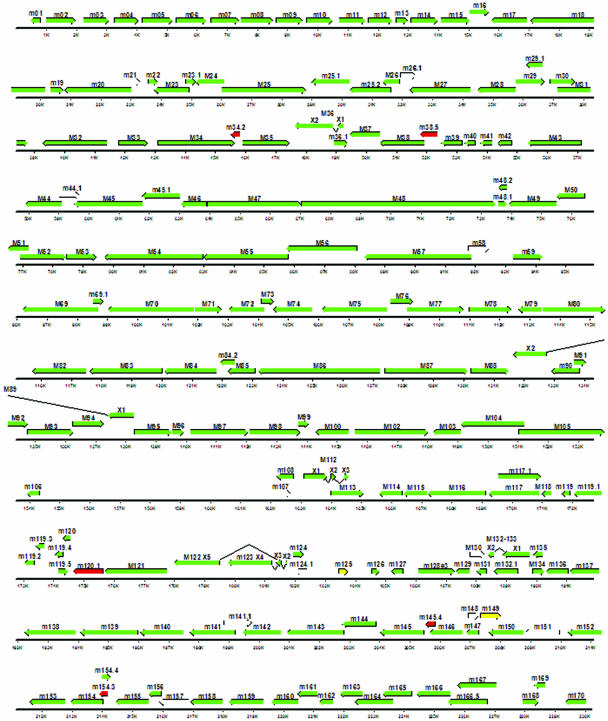

FIG. 2.

Distribution of open reading frames of MCMV. Each ORF is shown to scale, and the orientation of the corresponding arrow from left to right indicates an ORF encoded by the direct strand of the genome. Arrows that run from right to left indicate ORFs encoded on the complementary strand of the viral genome. Those ORFs labeled green, yellow, and red have been verified as producing transcripts. Empty arrows indicate ORFS for which no transcript could be identified with either microarray analysis or RT-PCR assays. Genes labeled with red arrows indicate the locations of genes that produce proteins targeted to mitochondria, and those labeled with yellow arrows are found only in the macrophage cell line.

ORFs undetectable in NIH 3T3 cells.

To determine whether the 30 ORFs not detected in our microarray were expressed at levels below the sensitivity range of our assay, we assayed all of them by RT-PCR, which has an increased sensitivity over that of the microarray assay (Fig. 3). RT-PCR was performed using DNase I-treated total RNA isolated from MCMV-infected 3T3 cells at 6 h p.i. (lane 2) and 24 h p.i. (lane 3). Lane 1 shows the noninfected cell control, while lane 4 shows the product using the whole MCMV DNA template as a positive control for the PCR. Thirteen of the ORFs that had shown weak or questionable signal in the microarray analysis appeared to be truly negative (Fig. 3B), while the others showed detectable signal (Fig. 3A and C). Some ORFs were strongly detectable at 6 h p.i., such as m119.5, m126, m134, m144, and the newly found ORFs m145.4, 154.4, and m166.5, suggesting early kinetics of expression.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR of MCMV gene expression. Total RNA was isolated from infected and uninfected NIH 3T3 or IC21 cells and treated with DNase I (RNase free). PCR products were loaded as follows: in uninfected cells (lane 1), MCMV cells at 6 h p.i. (lane 2), and MCMV cells at 24 h p.i. (lane 3). MCMV BAC DNA was used as positive control for the PCR (lane 4). (A) ORFs weakly positive or negative in the microarray analysis but positive by PCR; (B) ORFs negative in both assays; (C) verification of the presence of transcripts of the newly identified ORFs; (D) ORFs negative in 3T3 fibroblasts but positive in the macrophage cell line IC21.

To test the possibility that expected transcripts of potential ORFs are not expressed in fibroblasts but are expressed in other cell types, IC21 macrophages were infected with MCMV at 1 PFU per cell for 6 and 24 h and analyzed by RT-PCR with primers of those ORFs negative in fibroblasts. Two ORFs, m125 and m149, for which expression in NIH 3T3 cells was not identified, were expressed in macrophages (Fig. 3D). It is possible that these ORFs exert some function specific to macrophages.

Newly identified ORFs.

Six ORFs, m154.3, m145.4, m132.1, m84.2, m34.2, and m154.4, that have not been predicted during previous sequence analyses were detected as transcribed by DNA microarray assay and confirmed by RT-PCR. We also confirmed three identified ORFs, m166.5 (19), m120.1, and m38.5 (8) (Fig. 1 and 3C). Since we found no homologues of those ORFs in HCMV, we used a lowercase “m” for their designation. Eight of these newly discovered ORFs are from the complementary strand, here recognized with a lowercase “c”; only one ORF was from the direct strand. The designations of the newly found ORFs are based on the MCMV genome (30) and a recent report on MCMV gene analysis (8) to maintain uniformity in the nomenclature: m154.3 213885-214205c, m145.4 205515-205853c, m132.1 188591-189418c, m84.2 121923-122438c, m34.2 45513-45845c, and m154.4 213979-214284.

Amino acid sequence comparison of the newly discovered gene products with other CMV proteins.

To test whether the newly described MCMV gene products are homologous with any other CMV proteins, computation was performed at the SIB using the BLAST network service, which uses a server developed at the SIB and NCBI BLAST 2 software (1). Only m120.1 has recognizable homology with rat CMV r119.5 and r119.6 and low homology with r119.4. Those three rat CMV ORFs had been reported to have no homology with any other CMV ORFs (40).

Intracellular distribution of gene products from newly found and transcribed ORFs.

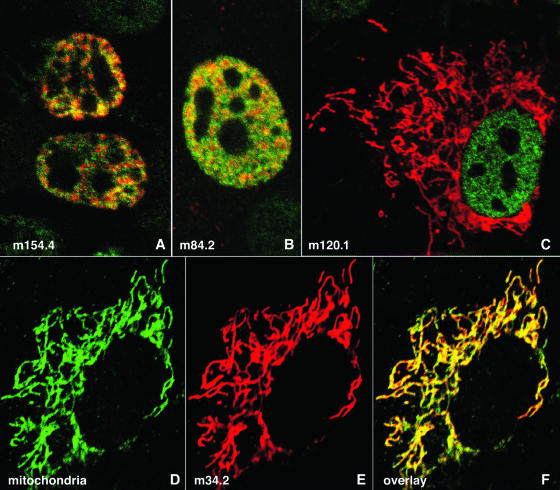

To characterize potential gene products of the newly described ORFs, we cloned them into pcDNA3 with a FLAG tag at the C terminus. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with these constructs and visualized after 24 h using immunofluorescence assays. HDAC2 staining was used to outline the nuclei. Only cells transfected and expressing the newly described ORF were stained with anti-FLAG antibody. Four of the gene products, m84.2, m132.1, m154.4, and m166.5, localized to the nucleus, whereas m38.5, m154.3, m145.4, m120.1, and m34.2 were exclusively cytoplasmic. All the nuclear proteins were excluded from the nucleoli. Some of them, such as m154.4, appeared predominantly at chromatin near the nuclear rim (Fig. 4A, upper nucleus) and in a punctuated distribution throughout the nucleus (lower nucleus) under low expression conditions. Other nuclear proteins, such as m84.2, were also present in a nondiffuse distribution (Fig. 4B). When expressed at higher concentrations, all nuclear proteins appeared diffuse but remained excluded from the nucleolus (data not shown). Proteins expressed in the cytoplasm had a distribution such as that illustrated for m120.1. This distribution is characteristic for mitochondria. We verified the potential segregation of the m154.3, m145.4, m120.1, and m34.2 ORF products to mitochondria by costaining transfected cells with human primary biliary cirrhosis autoantibodies recognizing mitochondria. All these products colocalized with mitochondria in a manner similar to that shown for the product of m34.2 (Fig. 4D to F). The peptide encoded by the recently identified MCMV ORF m38.5 (22) also has mitochondrial localization, as demonstrated by its FLAG tag cellular staining, similar to that of m34.2. These findings indicate that MCMV encodes at least five potential gene products that segregate to mitochondria. The respective genes are dispersed over the entire MCMV genome (Fig. 2). We used the MITOPROT program (http://ihg.gsf.de/ihg/mitoprot.html) to predict if the ORFs have mitochondrion-targeting sequences. Using this prediction program, m34.2 and m145.4 have a greater probability of being mitochondrion targeted than m38.5.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of newly found gene products in NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged m154.4 (A), m84.2 (B), m120.1 (C), or m34.2 (D to F). Anti-FLAG antibody was used to show the tagged gene products (red staining in panels A, B, C, E, and F), and HDAC2 was used to define the nuclear area (A and B). Mitochondrion-specific proteins are labeled green with fluorescein isothiocyanate in panels D and F.

Site-directed mutagenesis of m120.1 and m34.2.

Genetic analyses of DNA viruses are complicated due to the compactness of the genome, which results in overlapping ORFs. Like the genomes of other double-stranded DNA viruses, that of MCMV has ORFs on both strands and some overlap on the same strand, so that deletions may affect several ORFs. Our analysis of the MCMV gene sequence showed that three of the ORFs encoding products that localize to mitochondria overlapped neighboring ORFs, which includes m38.5. However, for m120.1 and m34.2, it was possible to introduce deletions without affecting either neighboring ORFs or those on the complementary strand. Thus, PCR fragments containing 40-bp homologues on either side of and within m120.1 or m34.2 and flanking the zeocin resistance gene were introduced into wild-type (wt) MCMV BAC DNA by recombination. The mutant BAC DNA was selected using zeocin. The rescued BAC DNA was obtained by cotransfection of the mutant BAC DNA with the full-length m34.2 or m120.1 cDNA. Mutant and rescued viruses were reconstituted by transfection of BAC DNA into NIH 3T3 cells.

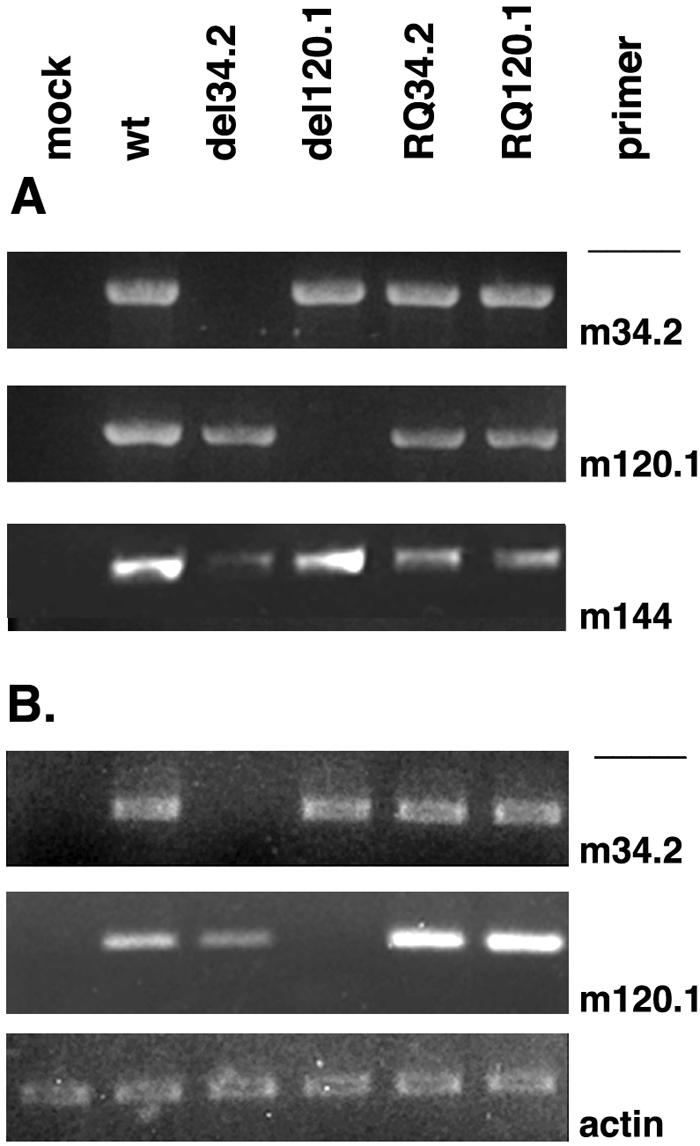

PCR analysis of DNA extracted by a modified Hirt extraction method (5) from NIH 3T3 cells infected with the mutant or rescued MCMV or the wild-type virus at 0.5 PFU for 48 h demonstrated the absence of m120.1 in MCMVdelm120.1 or of m34.2 in MCMVdelm34.2 and the presence of each in the rescued viruses (Fig. 5A). The absence of m120.1 or of m34.2 transcripts and their expression in the respective reconstructed viruses was also confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 5B). The results indicate that the loss of the respective ORFs in the deletion mutant was restored in the respective reconstructed virus.

FIG. 5.

PCR of viral DNA from the respective wild-type virus, the deletion mutants, and the revertant MCMV of m120.1 or m34.2. (A) Viral DNA was isolated from NIH 3T3 cells at 48 h p.i. with the viruses indicated. Primers within the deleted fragments of the ORFs used were from m120.1 and m34.2. m144 was used as positive control. (B) Total RNAs were isolated for RT-PCR from NIH 3T3 cells infected with the corresponding virus (0.5 PFU/cell) at 24 h p.i. Primers used for the corresponding ORFs are indicated on the right.

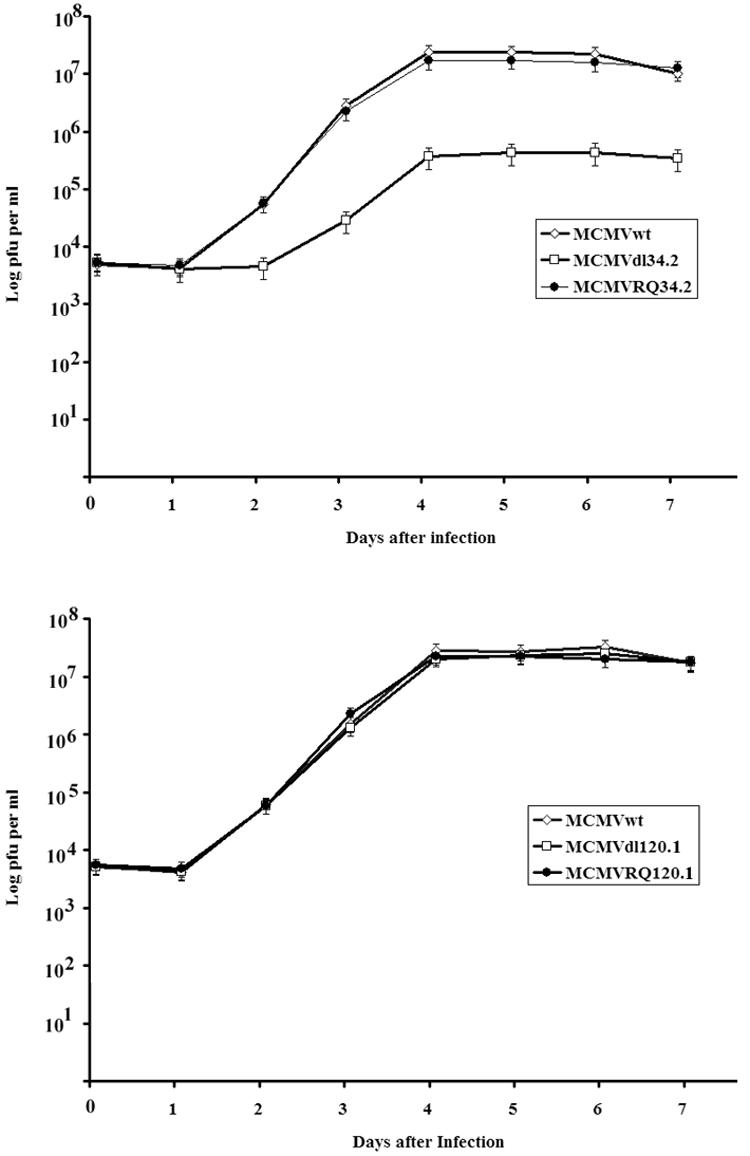

To determine the effects of m120.1 and m34.2 on MCMV productive replication in cell culture, plaque assays were performed comparing the wild-type virus with the deletion mutant and the rescued virus. NIH 3T3 cells infected with 0.5 PFU of wt MCMV, MCMVdel120.1, MCMVdel34.2, RQm120.1, and RQ34.2 were collected at days 0 to 7 and centrifuged after three freeze-thaw cycles, and the supernatants were examined for viral titers by plaque assay of 3T3 cells. As shown by the growth curve for MCMVdl120.1 (Fig. 6), the virus was unaffected by this deletion; however, a deletion in m34.2 resulted in small plaques and a decrease in virus production of nearly 2 orders of magnitude. Reconstruction of the virus rescued the growth defect.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of MCMV and its mutants in NIH 3T3 cells by PFU assay. NIH 3T3 cells were infected with 0.5 PFU/cell of wt MCMV, MCMVdlm34.2, or MCMVRQm34.2 (A) and MCMV, MCMVdl120.1, and MCMVRQm120.1 (B). Cells were collected together with medium at days 0 and 1 to 7. After three freezing-thawing cycles, the supernatants were used to infect NIH 3T3 cells.

DISCUSSION

Studies of HCMV have been hampered by the high species specificity of the virus and the lack of experimental animal models. However, extensive similarity between MCMV and HCMV makes MCMV infection in mice a convenient model for in vivo studies. Conclusions drawn from either system depend on precise information about the similarities or differences in the molecular biology and the in vivo behaviors, especially with respect to how each virus counters cellular defense mechanisms. Moreover, MCMV has recently been proposed as a potential vector for gene therapy and transgenic delivery of vaccines, and use of any vector in humans must be based on a thorough understanding of its biological consequences upon long-term production of an effector protein or short-term but repeated production of a desired antigen. Since the publication of the MCMV DNA sequences (30), only recently was it proposed that there might be more gene products than previously predicted (8).

A total of 170 MCMV ORFs had been predicted (30), based on the 230-kb DNA genomic sequence of the Smith strain but without consideration as to the cell type in which the virus can grow. We designed a DNA microarray system carrying oligonucleotides from all ORFs listed previously and about 14 additional ORFs to test the prediction of MCMV gene expression on a global scale after infection of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Approximately 90% of the predicted ORFs were detected by their transcripts. We also observed that MCMV gene expression levels varied and that 25 ORFs were expressed at very low levels. The more sensitive RT-PCR assay of the 25 ORFs confirmed the absence of expression of 10 predicted ORFs in mouse fibroblasts. Since macrophages represent an even more significant cell type than fibroblasts for normal infection, we retested all of the potential ORFs negative in fibroblasts using the macrophage cell line IC21. Two ORFs, m125 and m149, had substantial transcripts in IC21 cells at 24 h p.i. (Fig. 3D), suggesting that those two potential gene products might be involved in cell tropism or tissue tropism. This finding raises the possibility that some of the potential ORFs for which no transcript has been found in fibroblasts and macrophages are expressed in other specific cell types during the virus replicative cycle or reactivation from latency.

Of the newly identified transcription products, pm132.1, pm84.2, and pm154.4 code for nuclear proteins, although their potential involvement in the viral replication cycle remains unknown. A surprising number of translation products (from ORFs m154.3, m145.4, m120.1, and m34.2) segregated to mitochondria, like the gene product from m38.5 (22). The viral mitochondrial inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) is apparently a strong inhibitor of apoptosis induced by HCMV infection (3, 6, 7, 15, 18, 22, 31, 39) and also inhibits apoptosis induced by proteosome inhibitors. Recent evidence that the vMIA mutant has near wild-type growth properties but is sensitive to stress induced by proteosome inhibitors, such as MG132 (22), suggests that intrinsic stresses of infection that could result in apoptosis may be suppressed. The apparent functional MCMV homolog, pm38.5, also locates to mitochondria and inhibits the same proteosome-based apoptosis. We identified four additional MCMV products that were segregated to mitochondria when transiently expressed in mouse cells. Whether they work in conjunction with pm38.5 or on different pathways or represent redundancy needs to be investigated. We may then also expect HCMV to have additional proteins functioning at the mitochondrial level.

The absence of the m120.1 mitochondrially located gene product had no effect on MCMV replicative success in NIH 3T3 cells, whereas deletion of m34.2 drastically reduced viral production (Fig. 6), although it is not essential for MCMV growth in cell culture, it is suggestive of an augmenting role for viral replication. Further studies are needed to determine whether pm34.2 is involved in antiapoptotic activities, potentially in association with the other viral proteins encoded in the same region. Both pm34.2 and pm145.4 and, to a lesser extent, pm154.3 are transcribed early after infection, whereas mp120 and pm38.5 appear later; note that HCMV vMIA also appears only late during the infection cycle (22). Such temporal differences in expression might reflect a staggered approach by the virus against differently induced apoptotic pathways. Lack of an effect of pm120.1 at the same critical location in the mitochondrion and its later expression also mimics that of vMIA in culture. The potency of these proteins in determining virus survival and successful replication needs to be established. MCMV may prove to be a useful model for the identification of functions of mitochondrially targeted proteins in the natural host. Such functions, impossible to elucidate for HCMV, may be exerted during in vivo replication and latency in the natural host and, in light of the association of several MCMV proteins with mitochondria, may also include apoptotic signaling and maintenance of energy production.

In summary, we have reinvestigated the MCMV genome for its coding potential and provided experimental confirmation of all but 10 previously predicted ORFs based on detection of their transcription products. Two ORFs that were not detectable in fibroblasts were expressed in a macrophage cell line. Products of three ORFs were newly identified and found to localize in the nucleus. There are now a total of five MCMV gene products that localize to mitochondria, an organelle important for energy generation of the cell and for an apoptotic signaling pathway that responds to intrinsic stresses, including virus infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the NIH (grants AI 41136 and GM 57599), the Robert Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust, and the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health. NIH core grant CA-10815 is acknowledged for support of the microscopy and sequencing facility.

We thank A. Campbell for the IC21 cell line, M. Messerle for plasmids pSM3 and pKD46, and H. Zhu for pCMV-zeo.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvin, A. M., P. Fast, M. Myers, S. Plotkin, and R. Rabinovich. 2004. Vaccine development to prevent cytomegalovirus disease: report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belzacq, A. S., C. El Hamel, H. L. Vieira, I. Cohen, D. Haouzi, D. Metivier, P. Marchetti, C. Brenner, and G. Kroemer. 2001. Adenine nucleotide translocator mediates the mitochondrial membrane permeabilization induced by lonidamine, arsenite and CD437. Oncogene 20:7579-7587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biegalke, B. J., and A. P. Geballe. 1991. Sequence requirements for activation of the HIV-1 LTR by human cytomegalovirus. Virology 183:381-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borst, E., and M. Messerle. 2000. Development of a cytomegalovirus vector for somatic gene therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 25(Suppl. 2):S80-S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boya, P., R. A. Gonzalez-Polo, N. Casares, J. L. Perfettini, P. Dessen, N. Larochette, D. Metivier, D. Meley, S. Souquere, T. Yoshimori, G. Pierron, P. Codogno, and G. Kroemer. 2005. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1025-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boya, P., M. C. Morales, R. A. Gonzalez-Polo, K. Andreau, I. Gourdier, J. L. Perfettini, N. Larochette, A. Deniaud, F. Baran-Marszak, R. Fagard, J. Feuillard, A. Asumendi, M. Raphael, B. Pau, C. Brenner, and G. Kroemer. 2003. The chemopreventive agent N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide induces apoptosis through a mitochondrial pathway regulated by proteins from the Bcl-2 family. Oncogene 22:6220-6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brocchieri, L., T. N. Kledal, S. Karlin, and E. S. Mocarski. 2005. Predicting coding potential from genome sequence: application to betaherpesviruses infecting rats and mice. J. Virol. 79:7570-7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison III, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, et al. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chee, M. S., S. C. Satchwell, E. Preddie, K. M. Weston, and B. G. Barrell. 1990. Human cytomegalovirus encodes three G protein-coupled receptor homologues. Nature 344:774-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compton, T., D. M. Nowlin, and N. R. Cooper. 1993. Initiation of human cytomegalovirus infection requires initial interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. Virology 193:834-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dargan, D. J., F. E. Jamieson, J. MacLean, A. Dolan, C. Addison, and D. J. McGeoch. 1997. The published DNA sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169 lacks 929 base pairs affecting genes UL42 and UL43. J. Virol. 71:9833-9836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feire, A. L., H. Koss, and T. Compton. 2004. Cellular integrins function as entry receptors for human cytomegalovirus via a highly conserved disintegrin-like domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:15470-15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fussey, S. P., J. R. Guest, O. F. James, M. F. Bassendine, and S. J. Yeaman. 1988. Identification and analysis of the major M2 autoantigens in primary biliary cirrhosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8654-8658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldmacher, V. S., L. M. Bartle, A. Skaletskaya, C. A. Dionne, N. L. Kedersha, C. A. Vater, J. W. Han, R. J. Lutz, S. Watanabe, E. D. Cahir McFarland, E. D. Kieff, E. S. Mocarski, and T. Chittenden. 1999. A cytomegalovirus-encoded mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis structurally unrelated to Bcl-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12536-12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffiths, P. D., and S. Walter. 2005. Cytomegalovirus. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson, L. K., J. S. Slater, Z. Karabekian, G. Ciocco-Schmitt, and A. E. Campbell. 2001. Products of US22 genes M140 and M141 confer efficient replication of murine cytomegalovirus in macrophages and spleen. J. Virol. 75:6292-6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jan, G., A. S. Belzacq, D. Haouzi, A. Rouault, D. Metivier, G. Kroemer, and C. Brenner. 2002. Propionibacteria induce apoptosis of colorectal carcinoma cells via short-chain fatty acids acting on mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 9:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kattenhorn, L. M., R. Mills, M. Wagner, A. Lomsadze, V. Makeev, M. Borodovsky, H. L. Ploegh, and B. M. Kessler. 2004. Identification of proteins associated with murine cytomegalovirus virions. J. Virol. 78:11187-11197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lafemina, R. L., and G. S. Hayward. 1988. Differences in cell-type-specific blocks to immediate early gene expression and DNA replication of human, simian and murine cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 69:355-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landolfo, S., M. Gariglio, G. Gribaudo, and D. Lembo. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus. Pharmacol. Ther. 98:269-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormick, A. L., C. D. Meiering, G. B. Smith, and E. S. Mocarski. 2005. Mitochondrial cell death suppressors carried by human and murine cytomegalovirus confer resistance to proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 79:12205-12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messerle, M., G. Hahn, W. Brune, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Cytomegalovirus bacterial artificial chromosomes: a new herpesvirus vector approach. Adv. Virus Res. 55:463-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mocarski, E. S., M. N. Prichard, C. S. Tan, and J. M. Brown. 1997. Reassessing the organization of the UL42-UL43 region of the human cytomegalovirus strain AD169 genome. Virology 239:169-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, E., I. Rigoutsos, T. Shibuya, and T. E. Shenk. 2003. Reevaluation of human cytomegalovirus coding potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13585-13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy, E., D. Yu, J. Grimwood, J. Schmutz, M. Dickson, M. A. Jarvis, G. Hahn, J. A. Nelson, R. M. Myers, and T. E. Shenk. 2003. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14976-14981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Netterwald, J., S. Yang, W. Wang, S. Ghanny, M. Cody, P. Soteropoulos, B. Tian, W. Dunn, F. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2005. Two gamma interferon-activated site-like elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter/enhancer are important for viral replication. J. Virol. 79:5035-5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotkin, S. A. 2004. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection and its prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1038-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramsay, M. E., E. Miller, and C. S. Peckham. 1991. Outcome of confirmed symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Arch. Dis. Child. 66:1068-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawlinson, W. D., H. E. Farrell, and B. G. Barrell. 1996. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 70:8833-8849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roumier, T., H. L. Vieira, M. Castedo, K. F. Ferri, P. Boya, K. Andreau, S. Druillennec, N. Joza, J. M. Penninger, B. Roques, and G. Kroemer. 2002. The C-terminal moiety of HIV-1 Vpr induces cell death via a caspase-independent mitochondrial pathway. Cell Death Differ. 9:1212-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh, N., C. Wannstedt, L. Keyes, M. M. Wagener, M. de Vera, T. V. Cacciarelli, and T. Gayowski. 2004. Impact of evolving trends in recipient and donor characteristics on cytomegalovirus infection in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 77:106-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, L. M., M. L. Lloyd, N. L. Harvey, A. J. Redwood, M. A. Lawson, and G. R. Shellam. 2005. Species-specificity of a murine immunocontraceptive utilising murine cytomegalovirus as a gene delivery vector. Vaccine 23:2959-2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweet, C. 1999. The pathogenicity of cytomegalovirus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:457-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang, Q., and G. G. Maul. 2003. Mouse cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein 1 binds with host cell repressors to relieve suppressive effects on viral transcription and replication during lytic infection. J. Virol. 77:1357-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Tang, Q., and G. G. Maul. Mouse cytomegalovirus crosses the species barrier with help from a few human cytomegalovirus proteins. J. Virol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.van den Pol, A. N., and P. K. Ghosh. 1998. Selective neuronal expression of green fluorescent protein with cytomegalovirus promoter reveals entire neuronal arbor in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 18:10640-10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van den Pol, A. N., E. Mocarski, N. Saederup, J. Vieira, and T. J. Meier. 1999. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism, replication, and gene transfer in brain. J. Neurosci. 19:10948-10965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Den Pol, A. N., J. Vieira, D. D. Spencer, and J. G. Santarelli. 2000. Mouse cytomegalovirus in developing brain tissue: analysis of 11 species with GFP-expressing recombinant virus. J. Comp. Neurol. 427:559-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vieira, H. L., A. S. Belzacq, D. Haouzi, F. Bernassola, I. Cohen, E. Jacotot, K. F. Ferri, C. El Hamel, L. M. Bartle, G. Melino, C. Brenner, V. Goldmacher, and G. Kroemer. 2001. The adenine nucleotide translocator: a target of nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and 4-hydroxynonenal. Oncogene 20:4305-4316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vink, C., E. Beuken, and C. A. Bruggeman. 2000. Complete DNA sequence of the rat cytomegalovirus genome. J. Virol. 74:7656-7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, X., M. Messerle, R. Sapinoro, K. Santos, P. K. Hocknell, X. Jin, and S. Dewhurst. 2003. Murine cytomegalovirus abortively infects human dendritic cells, leading to expression and presentation of virally vectored genes. J. Virol. 77:7182-7192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wollmann, G., P. Tattersall, and A. N. van den Pol. 2005. Targeting human glioblastoma cells: comparison of nine viruses with oncolytic potential. J. Virol. 79:6005-6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.