Abstract

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia, is transmitted vertically via breastfeeding. We have previously demonstrated that lactoferrin, a major milk protein, enhances HTLV-1 replication, at least in part by upregulating the HTLV-1 long terminal repeat promoter. We now report that HTLV-1 infection can induce lactoferrin gene expression. Coculture with HTLV-1-infected MT-2 cells increased the levels of lactoferrin mRNA in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells, as well as MCF-7 cells, models of two probable sources (neutrophils and mammary epithelium) of lactoferrin in breast milk. MT-2 cell coculture could be replaced with cell-free culture supernatants of MT-2 cells to exert the same effect. Furthermore, extracellularly administered Tax protein also induced lactoferrin gene expression at physiologically relevant concentrations. In transient-expression assays, Tax transactivated the lactoferrin gene promoter in HL-60 or MCF-7 cells. Experiments with Tax mutants, as well as site-directed mutants of the lactoferrin promoter reporters, indicated that the NF-κB transactivation pathway is critical for Tax induction of the lactoferrin gene promoter activity in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells, but not in MCF-7 cells. These results suggest that HTLV-1 infection may be able to induce expression of lactoferrin in a paracrine manner in the lactic compartment. Our findings, in conjunction with our previous study, implicate that mutual interaction between HTLV-1 and lactoferrin would benefit milk-borne transmission of this virus.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma and is transmitted vertically via breast milk and horizontally via semen in areas of endemicity (reviewed in references 11 and 45). Breast milk contains a number of cells (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes), as well as a wide variety of bioactive factors, that exert antimicrobial activity (reviewed in reference 9). Lactoferrin is a major milk protein that acts as a nonspecific antimicrobial agent against pathogenic bacteria, fungi, and other viruses (including human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and rotavirus) (reviewed in reference 43). A major source of lactoferrin in breast milk has not been determined; however, neutrophils have been shown to be major producers of lactoferrin (18) and to exist in large quantities in breast milk (9). Mucosal epithelial cells are also thought to be a source of lactoferrin in body fluids, including breast milk. Lactoferrin is also released from neutrophils in inflammatory sites, where lymphocytes, the major target of HTLV-1, are recruited (18). We have previously demonstrated that lactoferrin enhances HTLV-1 replication and transmission, at least in part, by upregulating the HTLV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter (29). Although lactoferrin exerts its antiviral activity by inhibiting viral entry into cells, lactoferrin appears to have little effect on cell-to-cell spread of HTLV-1, a highly cell-associated virus. Such a “smart” strategy, which utilizes a host antimicrobial factor for its replication and transmission, might have been established through a long period of coevolution between humans and HTLV-1.

In the present study, we show that HTLV-1 infection can induce expression of lactoferrin. While mammary epithelial cells have previously been shown to support and transfer productive HTLV-1 infection in vitro (19), HTLV-1 is not able to efficiently replicate in myeloid cells. However, HTLV-1 infection could induce expression of lactoferrin mRNA in those cells in a paracrine manner, where a soluble form of the Tax transactivator appears to play a role. Tax has been shown to be released from infected cells and to exert biological activity in neighboring uninfected cells (1, 5, 6, 20-23, 26, 38). Tax transactivates the lactoferrin gene promoter in both myeloid and mammary epithelial cells. Therefore, it is possible that Tax released from HTLV-1-infected T cells contributes to lactoferrin production by stimulating neighboring cells. Such mutual interaction between HTLV-1 and lactoferrin has implications for milk-borne transmission of HTLV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

HL-60 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and induced for differentiation to the metamyelocyte stage or beyond by adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to 1.25% for 5 days until >90% of the cells reduced nitroblue tetrazolium dye (data not shown). MCF-7 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum. HTLV-1-infected MT-2 cells were propagated as described previously (26). Where indicated, MT-2 cells were cocultured with HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells in a transwell system where the two types of cells were separated by a semipermeable membrane filter with 0.4-μmol/liter pores (Costar, Acton, MA). HeLa-Luc cells (containing a chromosomally integrated HTLV-1 LTR-driven luciferase gene) were a gift of K. T. Jeang (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD) (33). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from healthy volunteers as described previously (25).

Propagation of recombinant Tax.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and GST-Tax fusion protein were propagated and purified as described previously (26). Where indicated, GST-Tax preparations were chloroform extracted or neutralized with rabbit anti-Tax serum that was kindly provided by K. T. Jeang.

RNA isolation and analysis.

The expression of lactoferrin or tubulin gene mRNA was analyzed by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) of total RNA extracted with an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The primers used were 5′-GATGGCAAACGGAAGCCTGTGA-3′ (forward Lactoferrin), 5′-TTGGTGGAGCAACACCTGTTTC-3′ (reverse Lactoferrin), 5′-GTTGGTCTGGAATTCTGTCAG-3′ (forward Tubulin), and 5′-AAGAAGTCCAAGCTGGAGTTC-3′ (reverse Tubulin). Total RNA from 5 × 105 cells was subjected to RT-PCR using a QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN K.K.). Quantitative determination of the amplified products was done with the iCycler iQ Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). Reverse transcription and cycling conditions for lactoferrin were 30 min at 50°C and 15 min at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 95°C), annealing (30 s at 50°C), and extension (30 s at 72°C). The cycling conditions for tubulin were 40 cycles of denaturation (15 s at 95°C) and annealing/extension (60 s at 62°C). The expression of lactoferrin mRNA relative to that of tubulin mRNA was calculated and is shown as relative lactoferrin expression.

Plasmids.

Plasmids pMT-2T (parent plasmid) and pMT-Tax were kindly provided by U. Siebenlist (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD). Plasmids encoding wild-type HTLV-1 Tax (pCG-Tax) or its mutants (pCG-M22 and pCG-Δ3) were gifts of J. Fujisawa (Kansai Medical University, Moriguchi, Japan) (10, 35, 36). The human lactoferrin promoter (−937 to +32) was amplified using PCR with primers containing SacI (5′) and MluI (3′) restriction sites. The PCR products were digested with SacI and MluI, agarose gel purified, and ligated into pGL2-basic (Promega, Madison, WI) that had been digested with the two restriction enzymes. The resultant plasmid, pGL-Lf, was used to construct plasmids pGL-LfΔNF-κB, pGL-LfΔAP-1, and pGL-LfΔC/EBP, which contained nucleotide substitutions as indicated in Table 1. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for gel mobility shift assays and site-directed mutagenesisa

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Lf-NF-κB | 5′-GGTGGCCATTCCCCTCTGAGGTCCCT-3′ |

| Lf-NF-κB-m | 5′-GGTGGCCATGGCCCTCTGAGGTCCCT-3′ |

| Lf-AP1-1 | 5′-TCACTGCTGAGCCAAGGTGAA-3′ |

| Lf-AP1-1-m | 5′-TCACTGCAGTGCCAAGGTGAA-3′ |

| Lf-AP1-2 | 5′-CCTGTCCTGCCTCAGGGCTTT-3′ |

| Lf-AP1-2-m | 5′-CCTGTCCTGCTGCAGGGCTTT-3′ |

| Lf-C/EBP | 5′-GTCTATTGGGCAACAGGGCGGGGCAAA-3′ |

| Lf-C/EBP-m | 5′-GTCTCCCGGGCAACAGGGCGGGGCAAA-3′ |

| RANTES-NF-κB | 5′-ATTTTGGAAACTCCCTTAGG-3′ |

| NF-κB-C | 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ |

| AP1-C | 5′-CGCTTGATGACTCAGCCGGAA-3′ |

| C/EBP-C | 5′-TGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCA-3′ |

| Sp1-C | 5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′ |

Only sense sequences of double-stranded oligonucleotides are shown. Sequences corresponding to cis-acting elements are underlined. Mutated nucleotides are shown in boldface letters.

Transfection and luciferase assays.

Twenty million HL-60 cells were transfected by electroporation with one pulse at 300 V with 20 μg of pGL-Lf or its derivatives, along with the indicated amounts of pMT-2T or pMT-Tax in 300 μl of RPMI 1640. Where indicated, GST or GST-Tax was added to cells transfected with pGL-Lf alone. Transfection of MCF-7 cells was performed using a modified calcium phosphate method, as described previously (27). PBMC were transfected using the Human T Cell Nucleofector kit (Amaxa Biosystems), as described previously (31). The transfected cells were harvested after 2 days to measure luciferase activity, as described previously (25).

Nuclear extracts and gel mobility shift assays.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from DMSO-treated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells, as described previously (24). Gel mobility shift assays were performed using 32P-labeled oligonucleotides, indicated in Table 1, as described previously. Antibodies used for supershift/interference analysis were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

RESULTS

HTLV-1 infection upregulates lactoferrin gene expression in HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells in a paracrine manner, at least in part through soluble Tax protein.

Neutrophils and mammary epithelial cells are possible sources of lactoferrin in breast milk. Since neutrophils are not known to support HTLV-1 infection and HTLV-1 infection of mammary epithelial cells was demonstrated only in in vitro experiments, we hypothesized that if HTLV-1 can influence lactoferrin gene expression, HTLV-1 should mediate its activity in a paracrine manner. Therefore, we first compared lactoferrin mRNA levels in HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells cocultured with MT-2 cells with those in HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells alone. To avoid contamination of MT-2 cells in HL-60 or MCF-7 cell preparations, the two types of cells were separated by a semipermeable membrane filter in culture. Under these conditions, myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells had no direct contact with MT-2 cells, and neither of the cell lines became infected with HTLV-1, as indicated by the absence of HTLV-1 proviral DNA in cocultured cells (data not shown). Total cellular RNA was extracted after 2 days of culture or coculture and subjected to real-time RT-PCR of lactoferrin mRNA and tubulin mRNA (as a control), and lactoferrin mRNA levels relative to those of tubulin mRNA were determined. As shown in Fig. 1A, MT-2 cell coculture induced lactoferrin gene expression by approximately fourfold and threefold in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells and MCF-7 cells, respectively. Similar effects were obtained when HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells were incubated in 50% cell-free supernatant from MT-2 cell culture instead of coculture with MT-2 cells (Fig. 1A), indicating that soluble factor(s) from MT-2 cells mediated induction of lactoferrin gene expression in HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells.

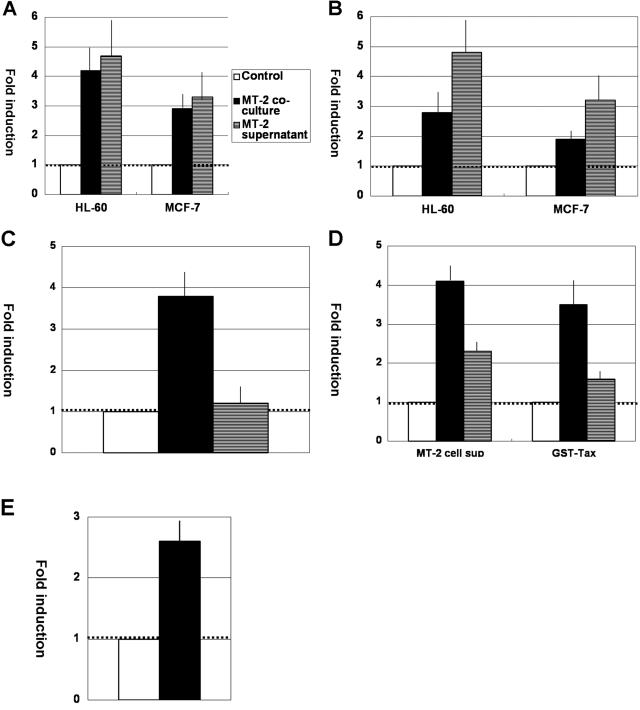

FIG. 1.

HTLV-1 Tax induces lactoferrin gene expression. (A) MT-2 cell coculture or MT-2 cell-free culture supernatants upregulated lactoferrin gene expression in DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells. Total RNA was extracted from untreated cells (open bars) or cells that had been cocultured with MT-2 cells through a semipermeable membrane filter (closed bars) or incubated in 50% MT-2 cell-free supernatants (hatched bars) for 2 days and was subjected to real-time RT-PCR of lactoferrin or tubulin gene mRNA. Lactoferrin mRNA expression relative to that of tubulin mRNA in untreated cells is shown as 1. The results are means ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments. (B) Recombinant Tax protein upregulated lactoferrin gene expression. Expression of lactoferrin mRNA relative to that of tubulin mRNA was calculated for total RNA extracted from DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells that had been treated with GST (1.5 nM) (open bars), GST (1.2 nM) plus GST-Tax (0.3 nM) (closed bars), or GST-Tax (1.5 nM) (hatched bars) for 16 h, as in panel A. (C) Chloroform extraction abolished the GST-Tax effect on lactoferrin gene expression. DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells were treated with GST (1.5 nM) (open bar), control nonextracted GST-Tax (1.5 nM) (closed bar), or chloroform-extracted GST-Tax (1.5 nM) (hatched bar). The results are means ± SD from triplicate experiments. (D) Neutralization of Tax with anti-Tax serum markedly reduced the ability of MT-2 cell-free culture supernatant or GST-Tax preparations to induce lactoferrin gene expression. (Left) DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells were incubated with Jurkat cell-free culture supernatant (open bar) or with MT-2 cell-free culture supernatants plus normal rabbit serum (closed bar) or anti-Tax serum (hatched bar). (Right) Similarly, DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells were treated with GST (1.5 nM) (open bar), GST-Tax (1.5 nM) plus normal rabbit serum (closed bar), or GST-Tax (1.5 nM) plus anti-Tax serum (hatched bar). The results are means ± SD from triplicate experiments. (E) Tax-inducible soluble factors played a role in inducing lactoferrin gene expression. DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells were treated with GST or GST-Tax for 2 h and washed extensively to remove it, and cell-free culture supernatants were collected after 24 h of incubation. Another line of DMSO-differentiated HL-60 cells were exposed to cell-free culture supernatants from GST (open bar)- or GST-Tax (closed bar)-preconditioned HL-60 cells for 16 h, and total RNA was extracted from those cells for real-time RT-PCR analysis. The results are means ± SD from triplicate experiments.

It has been shown that HTLV-1 Tax protein is released from HTLV-1-infected cells and exerts a number of biological activities in exposed cells and that cell-free supernatants from MT-2 cells and other HTLV-1-infected cells contain soluble Tax protein at nanomolar levels (4, 26). Therefore, we next tested whether exposure of recombinant Tax protein to HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells can induce lactoferrin gene expression. Myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells were incubated with GST or GST-Tax for 16 h, and total RNA was extracted for real-time RT-PCR, as described above. As expected, lactoferrin mRNA levels were increased by GST-Tax treatment of the cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Although GST-Tax was purified from Escherichia coli and therefore possibly contained endotoxin, we believe from three lines of evidence that the GST-Tax effect on lactoferrin gene expression was not due to contamination of endotoxin but due to Tax itself. First, while GST, which was similarly purified from E. coli, had no or very little effect on lactoferrin gene expression (data not shown), GST-Tax had significant effects on GST (Fig. 1B). Second, chloroform extraction of the GST-Tax preparations, which removes protein but not endotoxin, resulted in total loss of activity to induce lactoferrin gene expression (Fig. 1C). Finally, neutralization of GST-Tax preparations or MT-2 cell-free culture supernatants with anti-Tax serum markedly reduced its ability to induce lactoferrin gene expression (Fig. 1D).

As shown above, lactoferrin gene expression was induced by soluble Tax protein. However, since soluble Tax protein has been shown to induce expression of a number of genes, including cytokines (5, 6, 21, 26), it is possible that Tax-inducible soluble factors also play a role in inducing lactoferrin gene expression. To explore this possibility, myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells were treated with GST or GST-Tax and washed extensively to remove it, and cell-free culture supernatants were collected. As shown in Fig. 1E, cell-free culture supernatants from GST-Tax-preconditioned HL-60 cells induced lactoferrin gene expression at higher levels than those from GST-preconditioned cells, suggesting that soluble Tax can mediate its activity on lactoferrin gene expression, at least in part, indirectly through induction of other soluble factors, likely cytokines.

The experiments suggest that HTLV-1 infection can upregulate lactoferrin gene expression in neighboring cells in a paracrine manner and that soluble Tax protein released from HTLV-1-infected cells plays a critical role.

Mutual interactions between HTLV-1 and mammary epithelial cells.

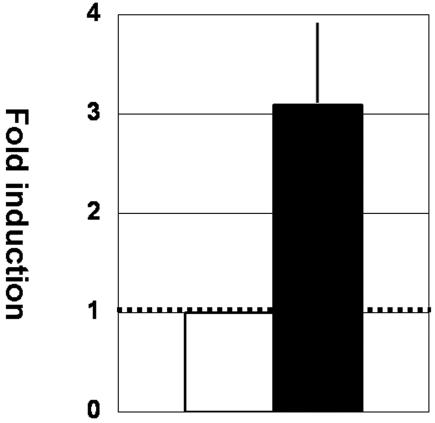

We have previously reported that lactoferrin can transactivate the HTLV-1 LTR promoter. Therefore, we wanted to demonstrate whether culture supernatants from HTLV-1 Tax-stimulated lactoferrin-producer cells could induce HTLV-1 expression. To do so, mammary epithelial MCF-7 cells were treated with GST or GST-Tax and washed extensively to remove it, and cell-free culture supernatants were collected to stimulate HeLa-Luc cells. As shown in Fig. 2, cell-free culture supernatants from GST-Tax-preconditioned MCF-7 cells induced expression from the HTLV-1 LTR at higher levels than those from GST-preconditioned cells, suggesting possible interaction between HTLV-1 and mammary epithelial cells.

FIG. 2.

Mutual interactions between HTLV-1 and mammary epithelial cells. MCF-7 cells were treated with GST or GST-Tax for 2 h and washed extensively to remove it, and cell-free culture supernatants were collected after 24 h of incubation. HeLa-Luc cells were exposed to cell-free culture supernatants from GST (open bar)- or GST-Tax (closed bar)-preconditioned MCF-7 cells for 24 h, and cell lysates were subjected to luciferase assays. The results are means plus standard deviations from triplicate experiments.

HTLV-1 Tax transactivates the lactoferrin gene promoter.

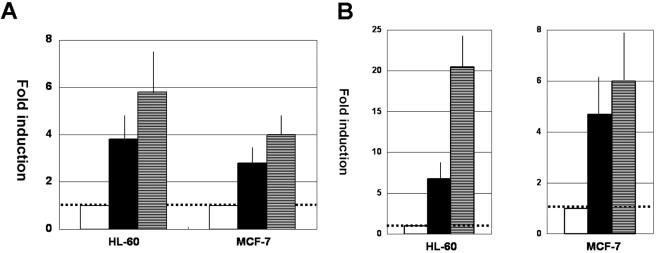

In order to investigate how HTLV-1 Tax could influence lactoferrin gene expression, we next performed transient-expression assays. Exposure to soluble GST-Tax protein at physiologically relevant concentrations (Fig. 3A) or cotransfection of Tax expression vector (Fig. 3B) enhanced the activity of the lactoferrin promoter in both myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells and MCF-7 cells in a dose-dependent manner, strongly suggesting that Tax mediates its effect on lactoferrin expression at the promoter level.

FIG. 3.

HTLV-1 Tax transactivates the lactoferrin promoter. (A) DMSO-treated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells were transfected with pGL-Lf; treated with GST (1.5 nM) (open bars), GST (1.2 nM) plus GST-Tax (0.3 nM) (closed bars), or GST-Tax (1.5 nM) (hatched bars) for 2 days; and subjected to luciferase assays. Fold induction is the luciferase activity relative to that obtained with GST treatment. The results are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. (B) DMSO-pretreated HL-60 cells were transfected with 20 μg of pGL-Lf, along with pMT-2T (10 μg) (open bar), pMT-2T (8 μg) plus pMT-Tax (2 μg) (closed bar), or pMT-Tax (10 μg) (hatched bar). On the other hand, MCF-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pGL-Lf, along with pMT-2T (1 μg) (open bar), pMT-2T (0.8 μg) plus pMT-Tax (0.2 μg) (closed bar), or pMT-Tax (1 μg) (hatched bar). Fold induction is the luciferase activity relative to that obtained with pGL-Lf plus pMT-2T. The results are from four independent experiments.

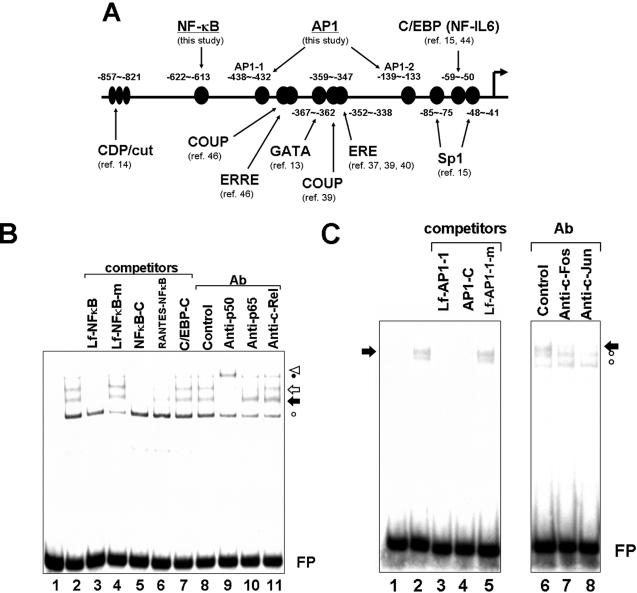

The lactoferrin gene promoter region contains binding sites for NF-κB, AP-1, and C/EBP (NF-IL-6).

Previous analysis of the human lactoferrin gene promoter sequence identified several regulatory cis-acting elements (Fig. 4A), including an estrogen response element (37, 39, 40), an extended estrogen response element half-site (46), a GATA site (13), COUP-TF binding elements (39, 46), CCAAT displacement protein (CDP/cut) sites (14), a site for C/EBP transcription factors (including nuclear factor-interleukin 6 [NF-IL-6]) (15, 44), and Sp1 sites (15). Since HTLV-1 Tax positively or negatively regulates the expression of a number of genes by interacting with a variety of cellular transcription factors, including C/EBP (NF-IL-6) (28, 42), we tried to find cis-acting elements that possibly mediate Tax function. In addition to the C/EBP (NF-IL-6) site, lactoferrin promoter sequences contain a putative NF-κB site, as well as two possible AP-1 binding sites, both of which may be responsible for Tax-mediated activity (7, 8, 12, 36).

FIG. 4.

Identification of cis-acting elements on the human lactoferrin gene promoter. (A) Schematic diagram of the human lactoferrin gene promoter. The horizontal arrow indicates the transcription start site (13), and numbers above or below the sequence indicate nucleotides relative to the transcription start site. cis-acting elements demonstrated in this study (NF-κB and AP1) are underlined, and references are indicated for those previously reported. (B and C) Identification of binding sites for NF-κB and AP1. (B) LfNF-κB probe was incubated with nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells that had been pretreated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (1 μM) and ionomycin (1 μM) for 15 min. Where indicated above the figure, a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides (lanes 3 to 6) (Table 1) or antibodies (lanes 8 to 11) was added to the reaction mixtures. Lane 1 represents probe alone, and lanes 2 to 11 represent reactions in the presence of nuclear extracts. FP indicates free probe. Open and solid arrows indicate the p65/p50 heterodimer (NF-κB) and p50 homodimer, respectively. The triangle indicates supershifted p50-containing complex. The open circle indicates nonspecific complex, and the closed circle indicates another, uncharacterized DNA-protein complex, which may be related to Rel family protein but apparently contains neither p50, p65, nor c-Rel. Similar results were obtained with DMSO-pretreated HL-60 cell nuclear extracts. (C) Lf-AP1-1 probe was incubated with MCF-7 nuclear extracts, as in panel B. Where indicated above the figure, a 100-fold molar excess of nonlabeled oligonucleotides (lanes 3 to 5) (Table 1) or antibodies (lanes 7 and 8) was added to the reaction mixtures. Lane 1 represents probe alone, and lanes 2 to 8 represent reactions in the presence of nuclear extracts. Solid arrows and open circles indicate Fos/Jun heterodimer (AP-1) and nonspecific complexes, respectively. Similar results were obtained with Lf-AP1-2 probe.

Since the aforementioned NF-κB site and AP-1 sites were postulated but not proven, gel mobility shift assays were performed to determine whether these elements bind to the expected transcription factors. The oligonucleotide containing the putative NF-κB site on the lactoferrin promoter formed at least two complexes that appeared to contain NF-κB/Rel family proteins. Formation of these complexes was specifically disrupted by competitor oligonucleotides known to bind NF-κB (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6) or by antibodies to p50 or p65 (Fig. 4B, lanes 9 and 10), indicating that one is a p50 homodimer and the other is a p65/p50 heterodimer. Similarly, supershift/interference analysis using specific antibodies and/or unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides revealed that two putative AP-1 sites are indeed cis-acting elements that bind to the Fos/Jun heterodimer (Fig. 4C and data not shown).

The molecular mechanism of Tax induction of lactoferrin promoter activity appears to be dependent on cell types.

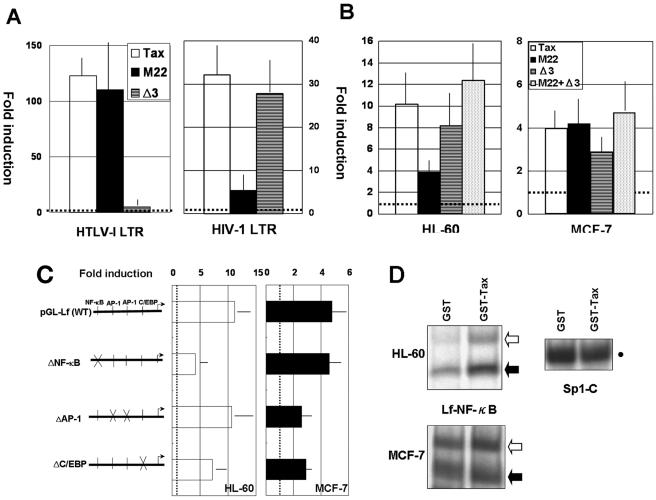

Tax cannot directly bind to promoter sequence but interacts with a number of cellular transcription factors to mediate its transcriptional activities. To demonstrate which activity is critical for the Tax-mediated effect on the lactoferrin promoter, two Tax mutants, M22 and Δ3, were tested in transient-expression assays. M22 cannot activate the NF-κB pathway but retains the ability to activate the cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding factor (CREB/ATF) and serum-responsive factor (SRF) pathways (36). On the other hand, Δ3 activates the NF-κB pathway but fails to activate CREB/ATF and SRF pathways (10, 35). For example, HTLV-1 LTR promoter activity is efficiently upregulated by M22, but not by Δ3, while Δ3, but not M22, efficiently upregulates HIV type 1 (HIV-1) LTR (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Cell-type-dependent regulation of the lactoferrin promoter activity by Tax. (A) Transactivation of HIV-1 LTR or HTLV-1 LTR by HTLV-1 Tax or its mutants. Five million PBMC from healthy volunteers were transfected with pU3R-luc (1 μg) or pGL-HIV-1-LTR (2 μg), along with 1 μg of pcDNA2.1, pCG-Tax, pCG-M22, or pCG-Δ3. Luciferase activity was measured 2 days after transfection. Fold induction is the luciferase activity relative to that obtained with pcDNA2.1. The results are means ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments. (B) Transactivation of the human lactoferrin promoter by HTLV-1 Tax or its mutants. DMSO-pretreated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells were transfected with pGL-Lf, along with pcDNA2.1, pCG-Tax, pCG-M22, pCG-Δ3, or a combination of the two mutants (M22 + Δ3). Fold induction is the luciferase activity relative to that obtained with pcDNA2.1. The results are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) Tax activation of the lactoferrin promoter site-directed mutants. DMSO-pretreated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells were transfected with pGL-Lf or its derivatives, along with pMT-2T or pMT-Tax. Fold induction is the luciferase activity relative to that obtained with pGL-Lf plus pMT-2T. The results are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (D) Tax induction of NF-κB binding activity in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells or MCF-7 cells. DMSO-pretreated HL-60 cells (top) or MCF-7 cells (bottom) were incubated with GST or GST-Tax for 30 min, and nuclear extracts were prepared for gel mobility shift assays using Lf-NF-κB (left) or Sp1-C (right). Open and solid arrows indicate p65/p50 heterodimer (NF-κB) and p50 homodimer, respectively. The closed circle indicates Sp1 complex.

The effects of wild-type Tax, M22, and Δ3 on lactoferrin promoter activity were tested in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 and MCF-7 cells. While wild-type Tax could upregulate lactoferrin promoter activity in either cell type, the activity of the Tax mutants relative to that of wild-type Tax varied, depending on the cell type. In HL-60 cells, M22 reduced its ability to transactivate the lactoferrin promoter, while Δ3 retained most of its activity. In MCF-7 cells, however, minimal reduction of transactivating activity was observed in Δ3, but not in M22 (Fig. 5B). Therefore, while the NF-κB transactivation pathway appears to be critical in Tax-mediated transactivation of the human lactoferrin promoter in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells, Tax may be able to upregulate the activity of this promoter unrelated to any of the classical transactivation pathways (NF-κB, CREB/ATF, or SRF) in MCF-7 cells.

Among cis-acting elements on the lactoferrin promoter sequence reported previously or identified in this study, the NF-κB site, the C/EBP site, and two AP-1 sites may be involved in Tax-mediated transactivation, as mentioned above. To delineate the Tax-responsive region(s) in the lactoferrin promoter sequence, site-directed mutations were introduced on those cis-acting elements. As shown in Fig. 5C, mutation of the NF-κB site markedly, and of the C/EBP (NF-IL-6) site modestly, reduced Tax induction of the lactoferrin promoter in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells, but mutations of both AP-1 sites had little effect on it. In gel mobility shift assays, GST-Tax treatment induced NF-κB binding activity significantly in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells but only minimally in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 5D). On the other hand, Sp1 binding activity in GST-Tax-treated cell nuclear extracts was comparable to or even slightly less than that in GST-treated cell nuclear extracts (Fig. 5D and data not shown). In contrast, mutation of the C/EBP site or AP-1 site, but not the NF-κB site, modestly reduced Tax induction of lactoferrin promoter activity in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 5C). Therefore, these experiments also suggest that the NF-κB transactivation pathway is important for Tax-mediated transactivation of the lactoferrin promoter in myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells and that other mechanisms are likely involved in the Tax effect on the lactoferrin promoter in MCF-7 cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that HTLV-1, which is transmitted vertically through breast milk or horizontally through semen, upregulated expression of lactoferrin, a major constituent in these body fluids. HTLV-1 infection mediated such effect in neighboring cells in a paracrine manner. This is important, since lactoferrin-producing cells, such as neutrophils and mammary epithelial cells, are not known as typical target cells of HTLV-1. Since HTLV-1-infected T cells stand a good chance of closely contacting neutrophils (one of the major cellular components of breast milk) or mammary epithelial cells in the lactic compartment, it is likely that our observation in in vitro experiments also holds true in in vivo settings. If that is the case, it is expected that breast milk from HTLV-1-infected lactating mothers contains a greater amount of lactoferrin than that from uninfected mothers. We are currently working on this hypothesis; however, pregnant women in areas of endemicity in Japan have been screened for HTLV-1 infection, and carrier mothers are instructed not to breastfeed, making it quite difficult to collect milk samples from infected mothers.

Our results suggested that HTLV-1 Tax transactivator played a role, at least to a certain degree, in such paracrine activity. Tax has been shown to be released from infected cells, to be taken into neighboring cells, and to induce a number of biological activities. For example, Marriott et al. have demonstrated that extracellular Tax can activate the expression of IL-2 receptor alpha on, and stimulate proliferation of, human lymphocytes (22, 23). Lindholm et al. have shown that extracellular Tax can induce NF-κB activity and stimulate expression of tumor necrosis factor beta and immunoglobulin kappa light chain in lymphoid cells (20, 21). We have also reported that extracellular Tax can increase the fusogenicity of cells mediated by HIV-1 Env glycoprotein (26). In addition to lymphocytes, extracellular Tax can induce similar biological activities in dendritic cells (32), neuronal cells (5), astrocytes (38), microglial cells (6), and synovial cells (2). We have now added myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells and mammary epithelial MCF-7 cells to the list of target cells of extracellular Tax. Although the physiological significance of extracellular Tax remains obscure, it can mediate those in vitro effects at as little as nanomolar levels or less, which are in the concentration range of Tax observed in the culture medium of HTLV-1-infected cells (4). Therefore, it is possible that Tax acts as an extracellular virokine with a potential role in the pathology of HTLV-1-associated diseases or its transmission in vivo.

Tax induces the expression of a number of cellular and viral genes through interaction with multiple transcription factors, their coactivators, or signaling molecules. NF-κB sites and CRE are most extensively characterized among cis-acting elements mediating Tax effects, but AP-1 sites and C/EBP sites have also been shown to mediate Tax-mediated effects (7, 8, 10, 28, 42). In myeloid-differentiated HL-60 cells, the NF-κB transactivation pathway appears to be critical for Tax-mediated induction of the lactoferrin gene promoter; however, we could not delineate which transactivation pathway or cis-acting element(s) is particularly important in MCF-7 cells. Cell-type-dependent effects of Tax on cellular transcription factors have been known for years. While Tax had a positive effect on NF-κB activity but no effect or a slightly negative effect on Sp1 activity in HL-60 cells in this study, Sp1 activity was reported to be variable among HTLV-1 Tax-positive cell lines (3).

Lactoferrin gene expression is regulated by several stimuli, and a number of cis-acting elements have been characterized in the human lactoferrin gene promoter region. C/EBP family transcription factors (C/EBPα and C/EBPɛ), CDP/cut, and Sp1 are necessary to activate the lactoferrin gene promoter during myeloid differentiation (14-16). On the other hand, lactoferrin gene expression is regulated by estrogen in the uterus and mammary gland (37, 39, 40). Therefore, it is not surprising to find such cell-type-dependent effects of Tax on the lactoferrin gene promoter.

Taken together with our previous study indicating that lactoferrin enhances HTLV-1 replication and transmission (29), it is tempting to consider that HTLV-1 and lactoferrin benefit from each other and that such mutual aid helps accelerate viral transmission through breast milk. In the lactic compartment that contains a large amount of lactoferrin, further enhancement of lactoferrin production by HTLV-1 infection may not be particularly useful for replication of this virus at this site. However, since lactoferrin in breast milk may be substantially diluted in the gastrointestinal tracts of babies and the lactoferrin effect on HTLV-1 replication and transmission is dose dependent, HTLV-1 induction of lactoferrin expression in the lactic compartment would be beneficial for mother-to-child transmission of the virus.

Interestingly, prostaglandin E2 (PG-E2) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), other major constituents of breast milk and seminal fluid, also enhance HTLV-1 replication and transmission (28, 30). Furthermore, HTLV-1 Tax has been shown to transactivate promoters for cyclooxygenase-2 (one of the PG-E2 synthetases) (28) and for TGF-β genes (17). These accumulating data raise the interesting possibility that HTLV-1 has evolved so as to make use of breast milk- or semen-derived host factors for its replication and transmission. Considering the fact that lactoferrin, PG-E2, and TGF-β have been shown to suppress infection with HIV-1 (30, 34, 41), another human retrovirus that is also transmitted through breast milk or semen, host factors in these body fluids probably influence viral infections in a variety of ways. Further studies are needed to more precisely delineate the effects of such host factors on milk-borne or sexually transmitted pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. T. Jeang, U. Siebenlist, and J. Fujisawa for providing reagents and M. Yokoyama for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants provided by a Research for the Future Program (JSPS-RFTF97L00705) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, The Japan Leukemia Research Foundation, The Mother and Child Health Foundation, and The ATL Prevention Program Nagasaki.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alefantis, T., K. Mostoller, P. Jain, E. Harhaj, C. Grant, and B. Wigdahl. 2005. Secretion of the human T cell leukemia virus type I transactivator protein Tax. J. Biol. Chem. 280:17353-17362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aono, H., K. Fujisawa, T. Hasunuma, S. J. Marriott, and K. Nishioka. 1998. Extracellular human T cell leukemia virus type I Tax protein stimulates the proliferation of human synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 41:1995-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck, Z., A. Bácsi, X. Liu, P. Ebbesen, I. Andirkó, E. Csoma, J. Kónya, E. Nagy, and F. D. Tóth. 2003. Differential patterns of human cytomegalovirus gene expression in various T-cell lines carrying human T-cell leukemia-lymphoma virus type I: role of Tax-activated cellular transcription factors. J. Med. Virol. 71:94-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady, J. N. 1992. Extracellular Tax1 protein stimulates NF-κB and expression of NF-κB-responsive Ig kappa and TNF beta genes in lymphoid cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:724-727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowan, E. P., R. K. Alexander, S. Daniel, F. Kashanchi, and J. N. Brady. 1997. Induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha in human neuronal cells by extracellular human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax1. J. Virol. 71:6982-6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhib-Jalbut, S., P. M. Hoffman, T. Yamabe, D. Sun, J. Xia, H. Eisenberg, G. Bergey, and F. W. Ruscetti. 1994. Extracellular human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax protein induces cytokine production in adult human microglial cells. Ann. Neurol. 36:787-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu, W., S. R. Shah, H. Jiang, D. C. Hilt, H. P. G. Dave, and J. B. Joshi. 1997. Transactivation of proenkephalin gene by HTLV-1 Tax1 protein in glial cells: involvement of Fos/Jun complex at an AP-1 element in the proenkephalin gene promoter. J. Neurovirol. 3:16-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujii, M., K. Iwai, M. Oie, M. Fukushi, N. Yamamoto, M. Kannagi, and N. Mori. 2000. Activation of oncogenic transcription factor AP-1 in T cells infected with human T cell leukemia virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1603-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamosh, M. 2001. Bioactive factors in human milk. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 48:69-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirai, H., J. Fujisawa, T. Suzuki, K. Ueda, M. Muramatsu, A. Tsuboi, N. Arai, and M. Yoshida. 1992. Transcriptional activator Tax of HTLV-1 binds to the NF-kappa B precursor p105. Oncogene 7:1737-1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollsberg, P., and D. A. Hafler. 1993. Pathogenesis of disease induced by human lymphotropic virus type I infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 328:1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwai, K., N. Mori, M. Oie, N. Yamamoto, and M. Fujii. 2001. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein activates transcription through AP-1 site by inducing DNA binding activity in T cells. Virology 279:38-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston, J. J., P. Rintels, P. Chung, E. J. Benz, Jr., and N. Berliner. 1992. Lactoferrin gene promoter: structural integrity and nonexpression in HL60 cells. Blood 79:2998-3006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna-Gupta, A., T. Zibello, S. Kolla, E. J. Neufeld, and N. Berliner. 1997. CCAAT displacement protein (CDP/cut) recognizes a silent element within the lactoferrin gene promoter. Blood 90:2784-2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna-Gupta, A., T. Zibello, C. Simkevich, A. G. Rosmarin, and N. Berliner. 2000. Sp1 and C/EBP are necessary to activate the lactoferrin gene promoter during myeloid differentiation. Blood 95:3734-3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna-Gupta, A., T. Zibello, H. Sun, P. Gaines, and N. Berliner. 2003. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies indicate a role for CCAAT enhancer binding proteins alpha and epsilon (C/EBPα and C/EBPɛ) and CDP/cut in myeloid maturation-induced lactoferrin gene expression. Blood 101:3460-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, S. J., J. H. Kehrl, J. Burton, C. L. Tendler, K. T. Jeang, D. Danielpour, C. Thevenin, K. Y. Kim, M. B. Sporn, and A. B. Roberts. 1990. Transactivation of the transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) gene by human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax: a potential mechanism for the increased production of TGF-β1 in adult T cell leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 172:121-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lash, J. A., T. D. Coates, J. Lafuze, R. L. Baehner, and L. A. Boxer. 1983. Plasma lactoferrin reflects granulocyte activation in vivo. Blood 61:885-888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeVasseur, R. J., S. O. Southern, and P. J. Southern. 1998. Mammary epithelial cells support and transfer productive human T-cell lymphotropic virus infections. J. Hum. Virol. 1:214-223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindholm, P. F., S. J. Marriott, S. D. Gitlin, C. A. Bohan, and J. N. Brady. 1990. Induction of nuclear NF-κB DNA binding activity after exposure of lymphoid cells to soluble Tax1 protein. New Biol. 2:1034-1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindholm, P. F., R. L. Reid, and J. N. Brady. 1992. Extracellular Tax1 protein stimulates tumor necrosis factor beta and immunoglobulin kappa light chain expression in lymphoid cells. J. Virol. 66:1294-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marriott, S., D. Trinh, and J. N. Brady. 1992. Activation of interleukin-2 receptor alpha expression by extracellular HTLV-1 Tax1 protein: a potential role in HTLV-1 pathogenesis. Oncogene 7:1749-1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marriott, S. J., P. F. Lindholm, R. L. Reid, and J. N. Brady. 1991. Soluble HTLV-1 Tax1 protein stimulates proliferation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes. New Biol. 3:678-686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, and J. I. Cohen. 1995. Proteins and cis-acting elements associated with transactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) immediate-early gene 62 promoter by VZV open reading frame 10 protein. J. Virol. 69:4693-4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. NF-κB potently upregulates expression of RANTES, an anti-HIV chemokine. J. Immunol. 158:3483-3491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, and A. S. Fauci. 1998. Factors secreted by HTLV-1-infected cells can enhance or inhibit replication of HIV-1 in HTLV-1-uninfected cells: implications for in vivo coinfection with HTLV-1 and HIV-1. J. Exp. Med. 187:1689-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, H. A. Smith, S. E. Straus, and J. I. Cohen. 1992. The varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 61 protein is functionally homologous to the herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0. J. Virol. 66:7303-7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriuchi, M., H. Inoue, and H. Moriuchi. 2001. Reciprocal interactions between human T-lymphotropic virus type I and prostaglandins: implications for viral transmission. J. Virol. 75:192-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriuchi, M., and H. Moriuchi. 2001. A milk protein lactoferrin enhances human T cell leukemia virus type I and suppresses HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 166:4231-4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriuchi, M., and H. Moriuchi. 2002. Transforming growth factor-β enhances human T-cell leukemia virus type I infection. J. Med. Virol. 67:427-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriuchi, M., and H. Moriuchi. 2003. YY1 transcription factor down-regulates expression of CCR5, a major coreceptor for HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:13003-13007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostoller, K., C. C. Norbury, P. Jain, and B. Wigdahl. 2004. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax induces the expression of dendritic cell markers associated with maturation and activation. J. Neurovirol. 10:358-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada, M., and K. T. Jeang. 2002. Differential requirement or activation of integrated and transiently transfected human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 76:12564-12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poli, G., A. L. Kinter, J. S. Justement, P. Bressler, J. H. Kehrl, and A. S. Fauci. 1991. Transforming growth factor β suppresses human immunodeficiency virus expression and replication in infected cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage. J. Exp. Med. 173:589-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu, T., S. Kawakita, Q.-H. Li, S. Fukuhara, and J. Fujisawa. 2003. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein stimulates the interferon-responsive enhancer element via NF-κB activity. FEBS Lett. 539:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith, M. R., and W. C. Greene. 1991. Molecular biology of the type I human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-I) and adult T-cell leukemia. J. Clin. Investig. 87:761-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokes, K., B. Alston-Mills, and C. Teng. 2004. Estrogen response element and the promoter context of the human and mouse lactoferrin genes influence estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transactivation activity in mammary gland cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 33:315-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szymocha, R., H. Akaoka, M. Duttuit, C. Malcus, M. Didier-Bazes, M.-F. Belin, and P. Giraudon. 2000. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1-infected T lymphocytes impair catabolism and uptake of glutamate by astrocytes via Tax-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Virol. 74:6433-6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teng, C. T., Y. Liu, N. Yang, D. Walmer, and T. Panella. 1992. Differential molecular mechanism of the estrogen action that regulates lactoferrin gene in human and mouse. Mol. Endocrinol. 6:1969-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng, C. T., W. Gladwell, C. Beard, D. Walmer, C. S. Teng, and R. Brenner. 2002. Lactoferrin gene expression is estrogen responsive in human and rhesus monkey endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8:58-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thivierge, M., C. Le Gouill, M. J. Tremblay, J. Stankova, and M. Rola-Pleszczynski. 1998. Prostaglandin E2 induces resistance to human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection in monocyte-derived macrophages: downregulation of CCR5 expression by cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Blood 92:40-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukada, J., M. Misago, Y. Serino, R. Ogawa, S. Murakami, M. Nakanishi, S. Tonai, Y. Kominato, I. Morimoto, P. E. Auron, and S. Eto. 1997. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax transactivates the promoter of human prointerleukin-1β gene through association with two transcription factors, nuclear factor-interleukin-6 and Spi-1. Blood 90:3142-3153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van der Strate, B. W. A., L. Beljaars, G. Molema, M. C. Harmsen, and D. K. F. Meijer. 2001. Antiviral activities of lactoferrin. Antiviral Res. 52:225-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verbeek, W., J. Lekstrom-Himes, D. J. Park, P. M. Dang, P. T. Vuong, S. Kawano, B. M. Babior, K. Xanthopoulos, and H. P. Koeffler. 1999. Myeloid transcription factor C/EBPɛ is involved in the positive regulation of lactoferrin gene expression in neutrophils. Blood 94:3141-3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi, K. 1994. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 in Japan. Lancet 343:213-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, N., H. Shigeta, H. Shi, and C. T. Teng. 1996. Estrogen-related receptor, hERR1, modulates estrogen receptor-mediated response of human lactoferrin gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5795-5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]