Abstract

Lymphotoxin alpha (LTα) can exist in soluble form and exert tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like activity through TNF receptors. Based on the phenotypes of knockout (KO) mice, the physiological functions of LTα and TNF are considered partly redundant, in particular, in supporting the microarchitecture of the spleen and in host defense. We exploited Cre-LoxP technology to generate a novel neomycin resistance gene (neo) cassette-free LTα-deficient mouse strain (neo-free LTα KO [LTαΔ/Δ]). Unlike the “conventional” LTα−/− mice, new LTαΔ/Δ animals were capable of producing normal levels of systemic TNF upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge and were susceptible to LPS/d-galactosamine (D-GalN) toxicity. Activated neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages from LTαΔ/Δ mice expressed TNF normally at both the mRNA and protein levels as opposed to conventional LTα KO mice, which showed substantial decreases in TNF. Additionally, the spleens of the neo-free LTα KO mice displayed several features resembling those of LTβ KO mice rather than conventional LTα KO animals. The phenotype of the new LTαΔ/Δ mice indicates that LTα plays a smaller role in lymphoid organ maintenance than previously thought and has no direct role in the regulation of TNF expression.

Lymphotoxin alpha (LTα), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and LTβ are related cytokines whose genes are clustered within 12 kb of genomic DNA inside of the major histocompatibility complex (10, 34). Their products have important but often overlapping functions in peripheral lymphoid organ development, microstructure maintenance, and immune response (2, 16, 50). LTα can exist in two main forms: the soluble homotrimeric form (sLTα), which shares receptors with TNF, and the transmembrane LTα1β2 heterotrimeric form, which interacts with a separate LTβ receptor (10, 18, 20, 50).

Because of the close proximity of LT/TNF genes, one can envision that any manipulation with one gene, involving deletions or insertions, may influence the expression of the others. Indeed, defective TNF production by conventionally engineered LTα knockout (KO) mice was previously reported (3). Additionally, another report showed that Mycobacterium bovis BCG-infected LTα KO mice displayed a 10-fold decrease in TNF production at an early stage of infection and a twofold reduction at a later time point (9). Besides, low or high copy TNF transgenes improved T/B-cell zone segregation in the LTα−/− mice via a TNF receptor I (TNFRI)-dependent mechanism, and partially restored the organization of splenic B-cell follicles, suggesting that defective TNF expression might contribute to the phenotype of LTα-deficient mice (3). Such a role of TNF was further supported by the phenotype of the double LTβ/TNF KO mice, whose splenic architecture was disrupted similarly to that in “conventional” LTα KO mice (26). Thus, downregulation of TNF expression in conventional LTα KO mice might be due to targeting artifacts. An alternative hypothesis is that the LTα and TNF genes are involved in mutual regulation, perhaps through TNFRI, TNFRII, LTβ receptor (LTβR), and NF-κB.

The essential role of TNF in control of several infections was documented (15, 35). At the same time, several studies utilizing LTα-deficient mice provided evidence for the TNF-independent role of soluble LTα in various physiological processes, including resistance to pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Listeria monocytogenes, and Toxoplasma gondii (41, 42, 44). Interestingly, a significant decrease in TNF mRNA expression after T. gondii infection was noted in the brains of neo cassette-containing LTα KO mice. Primed spleen cells from these mice displayed significantly reduced TNF synthesis upon restimulation with Toxoplasma antigen while peritoneal macrophages produced severely reduced amounts of TNF in response to different activating stimuli (44). Thus, defective TNF production by conventional LTα knockout animals could potentially lead to misinterpretation of the role of LTα in some pathophysiological models. The relative TNF deficiency in conventional LTα KO mice has been perplexing for many years but there was no tool available to directly address this problem.

In this report, we describe a novel strain of LTα-deficient mice which allow investigation of these important issues. We used LoxP-Cre technology to create neo-free LTα KO (LTαΔ/Δ) mice capable of producing normal amounts of TNF both in vitro and in vivo. Our data strongly suggest that the decreased level of TNF production in LTα deficiency is not due to mutual regulation of LT and TNF but rather correlates with the presence of the neo cassette in the genetically manipulated LTα gene locus. On the other hand, our data support the main conclusions regarding the critical role of the LTα/LTβ-LTβR axis in development and maintenance of peripheral lymphoid tissues. Overall, the new LTαΔ/Δ mice will help to better define distinct and overlapping functions of TNF and LTα.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Engineering of neo resistance cassette-free LTα knockout mice.

A murine genomic clone in the EMBL3A phage vector containing the genes for LTα, LTβ, and TNF-α (40) was used to construct the targeting vector. A 3.2-kb HindIII-KpnI fragment and a 3.5-kb KpnI-HindIII fragment were subcloned into vectors pGEM4 and pBSKS+ [pBluescript II KS(+) with a modified multiple cloning site], respectively, resulting in pLTAI and pLTAII. A cohesive end oligonucleotide duplex containing a synthetic loxP motif and BamHI and EcoRI sites was inserted into the BamHI site of pLTAI, generating the pLTAloxI vector. A neo resistance gene cassette flanked by two loxP motifs was excised from the pL2neo vector as a SalI-XbaI fragment and cloned into the AsuII site of pLTAII using the AsuII-SalI-XbaI-AsuII synthetic duplex. Subclones containing the neo resistance gene with the orientation of transcription opposite to LTα were picked. The pLTAII vector was digested with EcoRI and religated, resulting in the pLTAIImin vector. Then, the neo resistance gene cassette flanked by two loxP motifs was cloned into the AsuII site of pLTAIImin as described for the contrLTAneo vector, resulting in pLTAneomin. To assemble the final targeting vector, TV-LTa, the HindIII-KpnI genomic fragment was recovered from the pLTAloxI vector, the KpnI-EcoRI fragment was recovered from the pLTAneomin vector by digestion with KpnI and NotI, and both fragments were ligated with a HindIII-NotI-digested modified pBSKS+ vector containing a herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene cassette (4). The identity and orientation of loxP motifs were verified by restriction analysis using asymmetric EcoRI sites introduced into LoxP synthetic duplexes. The targeting vector was further verified by sequencing across all cloning sites. TV-LTa was digested with NotI and used for transformation of 129/Sv embryonic stem (ES) cells. Homologous recombination was detected by PCR using primers LTARTP1 (5′-AACCTGCTGCTCACCTTGTT) and LTARTP2 (5′-CAGTGCAAAGGCTCCAAAGA). Out of 155 neomycin-resistant clones, 14 tested positive and were further tested for cointegration of the third LoxP site using primers Pri1lta (5′-CTTGTGTCTGTCTTGCGT) and Pri2lta (5′-GTCTCTCGGCAGTTAAGC). Out of four positive clones, two clones, 533 and 613, were confirmed by Southern analysis and used for injection into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Chimeras were backcrossed to C57BL/6; germ line transmission was detected by PCR and further confirmed by Southern analysis. Mice with germ line transmission were crossed to actin-Cre “deleter” mice (31). Progeny with complete deletion of both the TNF gene and neo resistance cassette were detected by PCR using primers Pri1lta and pri7lta (5′-ATAACTGTGACTTGAACC) and confirmed by Southern analysis.

Genomic Southern analysis.

Tissues or sorted cells were lysed in proteinase K buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mg/ml proteinase K) and incubated for 5 to 7 hours at 60°C. Genomic DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform and digested with HindIII. Five to 20 mg of restricted DNA samples was loaded on 0.7% agarose gel, separated at 10 V, and then blotted to the Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham) and hybridized with 32P-labeled probe mTNFexon2, previously described (8). The results were quantified using ImageQuant software.

Northern blotting.

RNA was isolated from 8 × 106 cells using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). DNA was digested on columns using the RNase-free DNase set (QIAGEN). RNA was run in 1× MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) running buffer at 5 V/cm under denaturing conditions for 3 hours, transferred to a Hybond-XL membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) in 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), UV cross-linked, and hybridized with the 32P-labeled probe. The probe was obtained by reverse transcription-PCR from mouse activated peritoneal macrophages using primers TNFMF (GGGTGTTCATCCATTCTCTAC) and TNFMR (TGAGATCTTATCCAGCCTCAT).

qRT-PCR.

cDNA obtained from 2 μg of total splenic RNA using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay. Primers and probes were selected for murine TNF and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as follows: mouse TNF-α real-time PCR primer set (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA); TNF-α FRET probe (5′-6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM]-CCACG TCGTAGCAAACCACCA-black hole quencher [BHQ]-3′; BioSource); and GAPDH probes 5′-GGGAAGCCCATCACCATCTT-3′ (forward), 5′-ACATACTCAGCACCGGCCTC-3′ (reverse), and 5′-FAM-AGCGAGACCCCACTAACATCAAATGGG-BHQ-3′. The PCR mixture was prepared using ABI TaqMan universal master mixture (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cycling profile performed with the iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) involved initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C (denaturing) and 20 s at 56°C (annealing/extension).

Mice.

LTαΔ/Δ mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for five generations. LTα−/− (13), TNF−/− (32), LTβ/TNF−/− (26), TNF/LTΔ3 (triple-knockout mice) (27), LTβ KO (4), LTβR KO (18), TNFRI KO (38), and TNFRII KO (37) mice were on the C57BL/6 background. All mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free environment.

Immune challenges.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For LPS/d-galactosamine (D-GalN)-induced toxicity, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 μg LPS in combination with 20 mg D-GalN (Sigma). Mice were monitored hourly and euthanized when moribund. To induce hepatitis, mice received concanavalin A (Sigma) at the dose 18 mg/kg of body weight intravenously and were observed for 12 h. For ovalbumin (OVA)/complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) immunization, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 μg OVA in 25 μl of saline emulsified 1:1 in AdjuLite Freund's adjuvant (Pacific Immunology, Ramona, CA) containing 1 mg/ml of heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra.

In vitro cell cultures.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were produced as described previously (1). More detailed information is available in the supplemental material.

Measurement of TNF, TNFR, and nitric oxide.

TNF and soluble TNF receptor concentrations were assessed using mouse TNF, TNFRI, and TNFRII Duo Set enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) development system (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Levels of nitrite (NO2−) in cell supernatants were measured by a colorimetric assay using modified Griess reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Elispot.

For OVA-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-5 (IL-5) production paraformaldehyde-fixed protein-loaded dendritic cells were plated at 2 × 105 per well along with purified CD4+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio. After incubation for 36 h, antigen-specific IFN-γ and IL-5 production was assessed using an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (Elispot) set (BD-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of antigen-specific immunoglobulin isotypes.

Serum was collected from mice on day 19 after immunization and OVA-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG, IgG2a, and IgG1 were analyzed by ELISA. Briefly, 100 μl of OVA at 10 μg/ml was used to coat plates for 12 h at 4°C, and then the wells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, blocked with 300 μl of 1% bovine serum albumin-phosphate-buffered saline for several hours at room temperature. After washing, 100 μl of test serum diluted 1:100 to 1:4,000 were added to the wells and incubated overnight at 4°C. For detection, solutions of 1:1,000-diluted alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG, IgG2a, and IgG1 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) were used in conjunction with FAST p-nitrophenyl phosphate tablets (Sigma). Plates were read at 405 nm on a microtiter plate reader.

Tissue and cytospin staining.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections as described previously (26). More detailed information is available in the supplemental material.

Flow cytometry.

Labeling with the LTβR-Ig (a gift from Y.-X. Fu, University of Chicago) was performed as previously described (28). Flow cytometry was performed using the FACSCalibur analyzer and WinMDI 2.8 software. Multicolor staining for cell surface antigens and intracellular TNF was performed using antibodies and the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using the t test and Fisher's exact test online tool (http://www.matforsk.no/ola/fisher.htm).

RESULTS

Generation of neo-free LTα knockout mice.

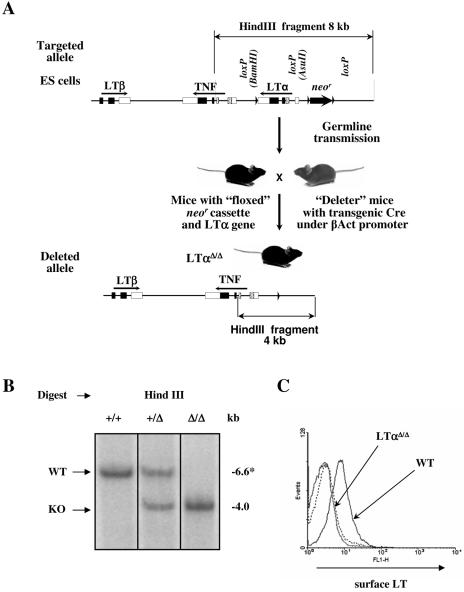

After homologous recombination in 129/Sv ES cells, two ES clones, verified by both PCR and Southern analysis, were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. After germ line transmission, mice were crossed with “deleter” mice carrying the Cre transgene under the strong ubiquitous β-actin promoter (31) to achieve both LTα gene and neo cassette deletion in all tissues (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Heterozygous mice were then intercrossed to obtain homozygous LTα KO animals and subsequently backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background. The resulting LTαΔ/Δ mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio and did not show any gross survival or growth abnormalities.

FIG. 1.

LoxP/Cre LTα gene targeting and deletion. (A) Scheme of the targeted disruption of the LTα gene. 129/Sv ES cells that have undergone homologous recombination with the targeting construct were injected into blastocysts and reimplanted into pseudopregnant females. The resulting chimeric mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice to detect germ line transmission. After confirmation of germ line transmission by PCR and Southern analysis, the offspring were then crossed with transgenic “deleter” mice in which Cre recombinase was placed under the β-actin promoter to achieve deletion of both the neomycin resistance (neo) cassette and LTα gene. The progeny were tested for the LTα gene and neo deletion, intercrossed to obtain homozygous mice, and then backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background. (B) Southern blot analysis of splenocytes from LTα+/+, LTα+/Δ and LTαΔ/Δ mice. Genomic DNA was digested with HindIII. *, 6.6-kb fragment of wild-type mouse DNA with the floxed LTα gene. (C) Surface expression of the LTαβ complex on activated splenocytes. Splenocytes were plated at 0.5 × 106/ml and activated for 7 h with phorbol myristate acetate (50 ng/ml) and anti-mouse CD40 (10 μg/ml).

Southern blotting analysis of HindIII-digested genomic DNA indicated complete LTα gene deletion (6.6-kb wild-type fragment in “floxed” LTα mice and 4.0-kb “knockout” fragment in LTαΔ/Δ mice) (Fig. 1B). To confirm the complete lack of LTα at the protein level, activated splenocytes were labeled with LTβR-Fc fusion protein to quantify surface LT complex by flow cytometry. There was no detectable surface LT expression on activated splenocytes from the LTαΔ/Δ mice (Fig. 1C).

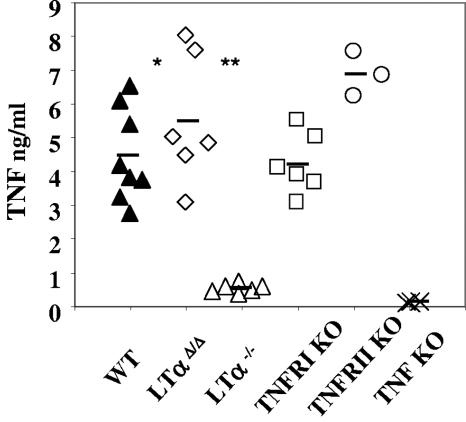

TNF production in vivo in response to LPS is normal in the LTαΔ/Δ mice in striking contrast to conventional LTα KO mice.

LPS is an important component of gram-negative bacterial cell wall sensed by Toll-like receptor 4 and CD14, which are expressed on the surface of several types of immune cells (25). LPS is a potent inducer of inflammatory factors and cytokines, including TNF (24). To assess TNF induction in the absence of LTα, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of LPS, and sera were harvested 90 min after the injection. While conventional LTα KO mice demonstrated up to a 10-fold decrease in serum TNF (Fig. 2), LTαΔ/Δ mice produced wild-type levels of this cytokine. At the higher 250-μg LPS dose TNF levels increased in all mice compared to those obtained at the 100-μg LPS dose, and conventional LTα−/− animals still showed up to a 60% reduction relative to either wild-type or LTαΔ/Δ mice (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). In agreement with these data, another independently generated strain of conventional LTα KO mouse (6) was evaluated and displayed comparable results (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Systemic LPS-induced TNF production is markedly decreased in conventional LTα−/−, but not in novel LTαΔ/Δ mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg LPS. Serum TNF levels were measured by ELISA 90 min after injection. *, P < 0.001, wild-type versus LTα−/− mice; **, P < 0.001, LTαΔ/Δ versus LTα−/− mice.

The activity of TNF can be neutralized by shedding of TNF receptors from the membrane of the expressing cells in vivo (33). To exclude the possibility that the wild-type levels of measurable TNF in our LTαΔ/Δ mice were due to differences in the levels of shed TNF receptors, we measured TNF receptor content in sera after LPS challenge and found no difference in soluble receptor concentrations among various mouse strains (see Fig. S2D and E in the supplemental material).

The hepatotoxic agent D-GalN increases the susceptibility of mice to the toxic effects of LPS up to 100,000-fold (19). TNF was previously shown to be one of the main effectors of toxicity seen in D-GalN-sensitized mice in response to LPS (7, 38). As an additional indication of TNF production, we compared the conventional and the novel LTα-deficient mouse strains in this well-characterized TNF-dependent in vivo model. We observed statistically significant differences in survival between LTαΔ/Δ and the conventional LTα−/− animals at time points when the percentage of severely moribund neo-free LTα KO mice reached 50 and 100% (P < 0.026). Nevertheless, conventional LTα KO mice showed only partial protection from LPS/D-GalN shock (Table 1). The lower LPS dose (0.1 μg) yielded comparable results, however, at the higher LPS dose (10 μg), LTα−/− animals died with kinetics similar to that of wild-type or LTαΔ/Δ animals (see Fig. S2F and G in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Survival after LPS/D-GalN challengea

| Strain (no. of animals) | No. moribund/no. healthy at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 h | 6 h | 7 h | 8 h | |

| Wild type (8) | 0/8 | 3/8 | 6/8 | 8/8 |

| LTαΔ/Δ (8) | 0/8 | 2/8 | 4/8* | 8/8** |

| LTα−/− (7) | 0/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 | 3/7 |

| TNF KO (7) | 0/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 |

Mice were injected with 1 μg LPS and 20 mg D-GalN. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. Data are shown as the ratios of severely moribund animals to healthy animals. * and **, LTαΔ/Δ versus LTα−/− (P ≤ 0.026).

In another model which is known to be largely dependent on TNF produced by T cells and macrophages/neutrophils (21), not only LTαΔ/Δ but also conventional LTα−/− mice were able to develop hepatitis after intravenous administration of a relatively high dose of concanavalin A (18 mg/kg) (data not shown). At a lower concanavalin A dose (9 mg/kg), LTα−/− mice showed a trend towards decreased TNF mRNA expression in their livers 1 hour after the injection (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Taken together, these data conclusively demonstrate that the novel LTαΔ/Δ mice express wild-type amounts of TNF. At the same time, these results suggest that TNF deficiency in conventional LTα KO animals is partial and may vary from profound TNF deficiency to almost normal TNF production, depending on the nature and/or dose of the activating stimulus.

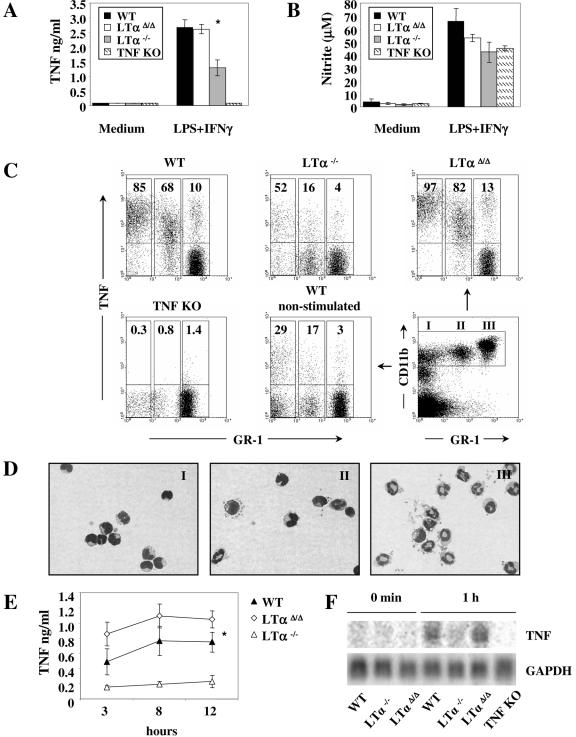

Cells of myeloid origin in conventional LTα−/− mice have diminished ability to produce TNF.

We next investigated whether or not TNF production in the conventional LTα−/− mice was negatively affected in all types of leukocytes that normally produce TNF. Our previous study with tissue-specific TNF-deficient mice showed that macrophages and neutrophils were the main source of systemic TNF after LPS challenge (21). To clarify if LTα-deficient macrophages have the potential to produce TNF in amounts comparable to those of wild-type macrophages, we stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMφ) with LPS and IFN-γ for 24 h. Strikingly, BMDMφ from conventional LTα−/− but not from LTαΔ/Δ mice failed to produce normal amounts of TNF (Fig. 3A). At the same time, nitric oxide levels in cell culture supernatants from both LTα-deficient strains were not significantly decreased (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Defective TNF synthesis by macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils in the conventional LTα KO mice. (A) TNF and (B) nitric oxide (NO) production by BMDMφ. Cells were activated with either medium alone or LPS (10 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. *, P = 0.025, LTαΔ/Δ versus LTα−/−. (C) Intracellular TNF staining of whole blood activated with LPS (10 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (10 ng/ml) for 3 h. Events shown are gated for CD11bhi expression. (D) Wright-Giemsa-stained, sorted peripheral blood CD11bhi leukocytes subdivided into three separate populations according to GR-1 expression (representative untreated wild-type mouse). In population I, 90% of cells represent monocytes; population II consists of monocytes (50%), neutrophils (25%), and other cell types (25%); and population III is composed of neutrophils (96%). Percentages are average approximate values from multiple analyses. (E) TNF production by BMDNE. Cells were activated with 10 ng/ml LPS and IFN-γ. Supernatants were harvested at 3, 8, and 12 h. TNF was measured by sandwich ELISA. *, P = 0.019, wild-type versus LTα−/−. (F) Northern blot analysis of BMDNE stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS and IFN-γ.

In the next set of experiments, we also compared the ability of peripheral blood monocytes and neutrophils to produce TNF in response to LPS and IFN-γ stimulation. Monocytes and neutrophils were activated in whole blood, which provides an environment similar to the conditions existing in vivo. To discriminate between monocytes and neutrophils, whole blood was stained with anti-CD11b and GR-1 antibodies as previously described (23, 30). Cells gated on the CD11bhi population fall into three distinct populations: GR-1low-neg (mainly monocytes), GR-1int (mixture of monocytes [about 50%], neutrophils [about 25%], and other cell types), and GR-1hi population, which was >98% pure neutrophils, as confirmed by modified Wright-Giemsa staining of cytospins (Fig. 3C and D).

In the conventional LTα KO mice, all three populations displayed substantial reductions in the percentage of TNF-positive cells. In addition, mean TNF fluorescence intensity was also substantially reduced (Fig. 3C). To specifically evaluate TNF production by neutrophils, we stimulated bone marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDNE) with LPS and IFN-γ. Similar to the results obtained with whole blood, the conventional LTα−/− mice but not the LTαΔ/Δ mice showed significantly impaired TNF production by BMDNE (Fig. 3E).

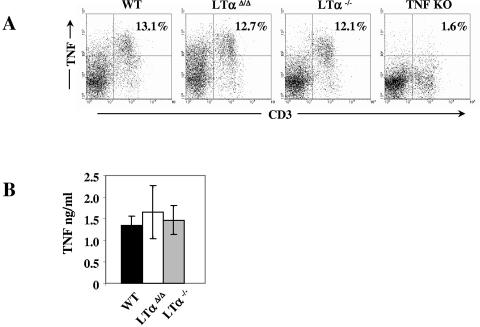

Since the expression of TNF is tightly regulated at the transcriptional, posttranscriptional, and translational levels, we then asked if defects in TNF production could be observed at the mRNA level. Northern analysis of TNF mRNA indicated that in the conventional LTα-deficient mice TNF expression was inhibited within 1 hour after activation (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, and in contrast to myeloid cells, intracellular and soluble cytokine analysis revealed that TNF production by activated T cells was similar in both LTα KO mouse strains and wild-type controls (Fig. 4), demonstrating a distinct difference between myeloid and lymphoid cell TNF production in LTα−/− mice.

FIG. 4.

Normal TNF production by splenic T cells in both strains of LTα KO mice. (A) Intracellular TNF production by splenic T cells, and (B) soluble TNF production by purified T cells stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (100 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml) for 5 h.

Peripheral lymphoid organs in novel neo-free LTα KO mice.

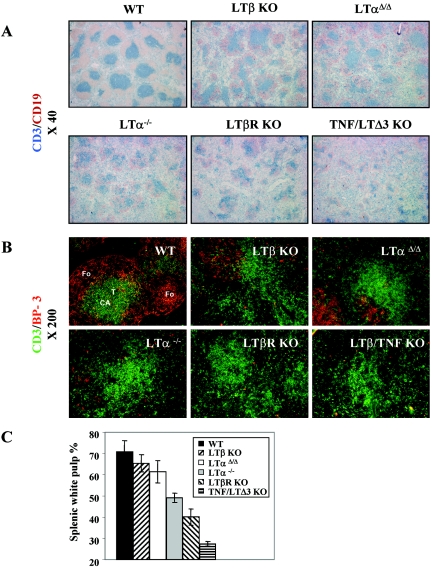

LTαΔ/Δ mice display the main macroscopic hallmarks of LT deficiency, including lack of all sets of peripheral lymph nodes and Peyer's patches, splenomegaly, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, and other features (data not shown). We next compared defects in splenic microarchitecture between the two LTα KOs. Interestingly, double immunohistochemical staining of spleen tissue sections using anti-CD3 and anti-CD19 antibodies revealed that the splenic white pulp in LTαΔ/Δ mice was bigger than in LTα−/− animals and was reminiscent of that of LTβ KO mice. Spatial segregation of T and B cells also appeared more organized in LTαΔ/Δ than in conventional LTα−/− mice (Fig. 5A and C and data not shown). Staining with ER-TR7 antibodies, which identify reticular fibroblasts and fibroblast-derived fibers, did not show visible differences between the two LTα-deficient strains. Although the staining revealed ring-like structures, ER-TR7-positive stromal elements were mostly concentrated around central arterioles rather than delineating the border between the red and white pulp (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material).

FIG. 5.

Better-conserved size of splenic white pulp and BP-3 expression in LTαΔ/Δ mice. (A) Serial splenic sections from mice of the indicated genotypes were stained with anti-CD3 (blue) and anti-CD19 (red) antibodies to detect T and B cells, respectively. Magnification, ×40. (B) To detect T cells and BP-3-positive stromal cells, splenic sections were stained with fluorescently labeled anti-CD3 (green) and anti-BP3 (red) antibodies. Magnification, ×200. (C) Quantification of the size of splenic white pulp. The size of splenic white pulp is shown as a percentage of the size of the entire image. Data were obtained using the NIH Medical Image Processing and Visualization program. Three mice per group were analyzed.

Staining for BP-3-positive subpopulations of stromal cells in peripheral lymphoid organs was previously shown to be dependent on TNF and LTα1β2 signals (36). Remarkably, the network of BP-3-positive cells was reduced but still readily detectable in the splenic white pulp of LTαΔ/Δ mice similar to LTβ KO mice, whereas there were only occasional BP-3-positive cells in some lymphoid follicles in conventional LTα−/− mice. In double LTβ/TNF ΚΟ and LTβR KO mice these stromal elements could not be detected. Gradual reduction of the BP-3-positive stromal cells was observed in the following order: wild-type mice > LTαΔ/Δ mice ≈ LTβ KO mice > LTα−/− mice ≥ LTβ/TNF KO mice ≈ LTβR KO mice (Fig. 5B). Although conventional LTα KO mice displayed a trend towards decreased basal TNF mRNA expression in the whole spleen, and LTαΔ/Δ mice showed the opposite tendency, this difference appeared not to be statistically significant (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). On the other hand, the better-preserved microstructure of the spleen in the LTαΔ/Δ mice correlated with higher levels of intracellular TNF expression by activated B cells in vitro (see Fig. S4C in the supplemental material).

Other features of splenic microarchitecture in LTαΔ/Δ mice, including the absence of CR1 and FDC-M1 expression, were indistinguishable from those seen in the conventional LTα−/− animals (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

Adaptive cellular and humoral immune response to OVA/CFA immunization.

A Th1-polarized response is needed to efficiently protect the host from some pathogens, including mycobacteria (14). To compare the ability of the two LTα KO mice strains to mount a Th1-polarized response, we utilized the OVA/CFA immunization model.

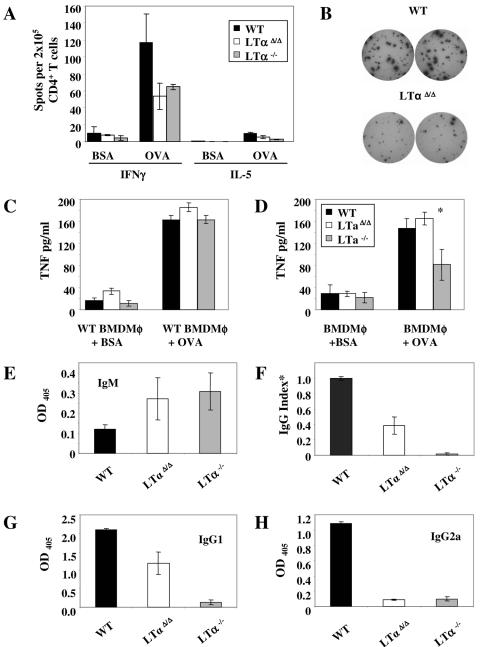

Proliferation of purified splenic day 14 CD4+ T cells from immunized animals in coculture with OVA-loaded fixed wild-type BMDC was at the wild-type level in both LTα KO mice strains (data not shown). Nevertheless, production of OVA-specific IFN-γ by CD4+ T cells was decreased up to twofold in LTα KO mice. The lower ovalbumin immunization dose (25 μg) revealed even more clearly the differences between LTα KO mice and wild-type mice, but again did not detect any dissimilarity between the LTαΔ/Δ and LTα−/− mouse strains. OVA-specific IL-5 was almost undetectable, confirming the Th1 polarization of the response (Fig. 6A and B and data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Adaptive immune responses of novel LTαΔ/Δ mice to OVA. (A) OVA- and BSA-specific IFN-γ and IL-5 production by sorted splenic CD4+ T cells from intraperitoneally OVA- and CFA-immunized mice. T cells were stimulated with OVA- or BSA-loaded fixed bone marrow-derived dendritic cells for 36 h. Antigen-specific cytokine production was determined by Elispot assay. (B) Representative wells showing OVA-specific IFN-γ production by splenic CD4+ T cells from wild-type and neo-free LTα KO mice. (C) TNF production by wild-type BMDMφ loaded with OVA or BSA (as a negative control) and stimulated for 24 h with purified day 14 CD4+ splenocytes from OVA/CFA-immunized wild-type (black columns), LTαΔ/Δ (white columns), or LTα−/− (gray columns) mice. (D) Antigen-specific TNF production by BMDMφ activated with wild-type CD4+ splenic T cells from OVA/CFA-immunized mice. *, P = 0.05, wild-type versus LTα−/−. (E to H) OVA-specific production of (E) IgM, (F) IgG, (G) IgG1, and (H) IgG2a was analyzed by ELISA. Serum dilution is 1:1,000. *, IgG response data representing three independent experiments. Readings at 405 nm were normalized to the wild-type reading, which was arbitrarily defined as 1.0 in each experiment.

Then, we assessed the ability of effector CD4+ LTα-deficient T cells to induce TNF production in antigen-loaded macrophages, and the capacity of macrophages to respond to T-cell stimulation. We activated OVA- or BSA-loaded BMDMφ with CD4+ T cells sorted from the spleens of OVA/CFA-immunized mice. OVA-loaded wild-type BMDMφ stimulated with primed wild-type, LTαΔ/Δ or LTα−/− T cells produced comparable levels of TNF (Fig. 6C). At the same time, and similar to results obtained with LPS stimulation (see above), only LTα−/− macrophages were incapable of producing proper amounts of TNF in response to activation by either wild-type or LTα-deficient CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6D and data not shown). Thus, the defect in TNF production by macrophages in this model appears to be macrophage autonomous and is not due to the inability of antigen-specific helper T cells to stimulate BMDMφ.

Together these findings indicated that LTα-deficient CD4+ T cells were able to proliferate and could efficiently stimulate wild-type BMDMφ in an antigen-specific manner but were unable to produce adequate amounts of IFN-γ. There was no difference between conventional and neo-free LTα KO mice with regard to T-cell responses.

In order to mount an efficient humoral immune response to nonreplicating thymus-dependent antigens, effective communication between dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) is required. We found that both LTα KO strains had elevated OVA-specific IgM antibodies in their sera 19 days after immunization, whereas the switch to an IgG isotype dropped severalfold (Fig. 6E, F, G, and H). This is a hallmark of defective humoral response observed earlier in the conventional LTα KO mice which was attributed to disturbed T- and B-cell zone segregation, absence of FDC and other abnormalities in splenic microarchitecture (17). Although both types of LTα-deficient mice displayed severely impaired antigen-specific IgG response compared to wild-type animals (Fig. 6F), there was some IgG1 production in the LTαΔ/Δ mice but not in the LTα−/− mice (Fig. 6G).

Thus, the LTα KO mouse strains have similar deficiencies in IgM/IgG isotype switching, most likely because of severely disturbed splenic microarchitecture.

DISCUSSION

This study defined a novel LTα-deficient mouse strain that differs from its conventional counterpart by the targeting strategy, in particular, by deletion of the entire LTα gene and excision of the neomycin resistance cassette. The presence of an actively transcribed selectable marker has been reported to cause alterations in the regulation of neighboring genes (39, 43). Given the fact that the two closely linked TNF and LTα genes encode cytokines with partly overlapping functions, such alterations may lead to inaccurate interpretation of the phenotype of mice deficient in one particular gene.

In the present report, we show that novel new neo-free LTαΔ/Δ mice generated by means of LoxP-Cre technology grossly resemble conventional LTα-deficient mice (6, 13) and LTβR KO mice (18), in agreement with most of the established functions of LTα signaling through LTβR in the development and maintenance of peripheral lymphoid tissues (16, 18, 22, 49, 50). However, one striking difference was the level of TNF production. Specifically, LTαΔ/Δ mice are fully capable of producing normal TNF levels, whereas conventional LTα KO animals display significant decreases in TNF synthesis in several critical types of leukocytes both in vitro and in vivo. For example, there was about a 10-fold difference in systemic TNF production between wild-type and conventional LTα KO mice upon intraperitoneal LPS challenge (Fig. 2).

Since the conventional LTα KO mice have normal levels of shed TNFRI and TNFRII which can regulate TNF bioavailability and activity (see Fig. S2D and E in the supplemental material), and do not show decreased numbers of monocytes and neutrophils in peripheral blood and of macrophages in peritoneal cavity (data not shown), the substantial decrease in TNF levels in vivo can be attributed to a cell-autonomous TNF production defect. Deficiency in systemic TNF production also translated into lower toxicity of LPS administered to D-GalN-sensitized conventional LTα KO mice (Table 1). However, at the higher LPS dose, D-GalN-sensitized LTα−/− animals died with the same kinetics as wild-type or LTαΔ/Δ animals (see Fig. S2F and G in the supplemental material), suggesting that TNF deficiency in conventional LTα KO mice is partial and dose dependent, and that its depth may vary depending on the pathophysiological model.

There are conflicting reports on the ability of myeloid cells from conventional LTα KO mice to produce TNF. Initially, Alexopoulou et al. (3) reported that conventional LTα-deficient thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages had decreased expression of TNF. Further, this finding was supported by Schluter et al. (44), who found dramatic decreases in TNF production by macrophages of another conventional LTα KO mouse strain. However, normal TNF production by BMDMφ stimulated with a high dose of LPS and IFN-γ for an unusually prolonged incubation time was also documented (41).

In this report, we demonstrated that TNF production by LPS- and IFN-γ-stimulated BMDMφ, monocytes, and neutrophils was impaired in the conventional LTα KO mice at both the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 3A, C, E, and F). Moreover, in another model when OVA-loaded BMDMφ were stimulated with wild-type CD4+ T cells sorted from the spleens of OVA- and CFA-immunized mice, reduced TNF production was detected only in the conventional LTα KO macrophages (Fig. 6D), confirming our previous finding.

Utilizing real-time PCR and Northern blotting analysis, it was previously shown that splenocytes from conventional LTα KO mice activated with the T-cell mitogen concanavalin A or phorbol myristate acetate produce normal amounts of TNF mRNA (6, 13, 45). Employing intracellular TNF protein staining and ELISA, we confirmed and extended this observation to activated T cells from both conventional and neo-free LTα-deficient mice (Fig. 4).

Taken together, our findings suggest that in conventional LTα KO mice, TNF production is impaired in myeloid cells but not lymphoid cells, supporting the idea of discrete regulation of TNF production in different cell types.

Indeed, the mechanisms controlling transcriptional initiation of the TNF gene may be different in distinct populations of leukocytes. Earlier promoter studies indicated that the sequence of the TNF promoter from −200 to −20 nucleotides relative to the TNF transcription start site is essential for TNF production by T cells in response to T-cell receptor engagement, ionophore stimulation, or viral infection. The histone acetyltransferases CBP and p300 are required for interaction and complex formation with all major lymphocyte transcription factors such as SP1, Ets-1, NFATp, ATF-2/Jun, and others, facilitating their binding to regulatory elements in this TNF gene promoter-proximal region (47).

In contrast, a major role of the distal region of the TNF gene promoter was documented in macrophages triggered through Toll-like receptors. The distal region contains several important elements, including four κB binding sites that interact with a unique repertoire of NF-κB/Rel complexes as well as other transcription factors. In particular, there is a highly conserved element 0.6 kb upstream of the TNF transcription start site that contains a cluster of transcription factor binding sites, including κB sites 2 and 2a. This region was shown to be critical for maximal NF-κB-dependent activity of the TNF promoter (29, 46, 48). Thus, the transcriptional regulation of TNF in different cell types or even in a single cell type depends on the nature of the stimulus which leads to the recruitment of distinct sets of transcription factors and architectural proteins to distinct or shared regulatory elements of the TNF gene promoter. Besides, the formation of different NF-κB/Rel complexes in response to the same stimulus may depend on the cell type. In this regard, increased levels of inhibitory p50 homodimers that interact with three κB elements in the distal TNF promoter region were observed in macrophages but not in fibroblasts during the late stage of response to LPS (5).

Our targeting strategy could potentially introduce defects in TNF regulation by deleting putative control elements located within the deleted portion of the LTα gene or put some transcription-enhancing regulatory elements located upstream of the LTα gene closer to the TNF gene. However, no such elements were previously reported for TNF transcription in macrophages/monocytes, in which case the distal elements of the promoter are confined to an approximately 1-kb region fully retained in our targeting vector. More importantly, normal or almost normal levels of TNF production in several cell types analyzed in this study strongly argue that TNF is not downregulated due to LTα deficiency and the existence of a “cytokine network.” This conclusion is further supported by the fact that neo-free LTβ KO mice and LTβR KO mice also have normal levels of TNF in serum after LPS challenge (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Thus, reduced TNF levels in the conventional LTα KO mice appear to be due to the targeting strategy employed and are likely to be associated with the presence of the neo cassette upstream of the TNF gene. Further studies may be needed to determine the exact mechanism of TNF downregulation in myeloid cells of conventional LTα KO mice.

The importance of macrophages, neutrophils, and TNF in host protection against intracellular pathogens has been extensively documented (11, 12, 21, 35). Thus, in the case of intracellular infection, efficient innate immune response is of paramount importance and early adequate TNF production can be critical not only for initial bacteria containment but also for the overall resolution of the disease. Although TNF and LΤα were reported to be independently important for host defense against BCG infection, up to fourfold reduction of serum TNF levels after BCG infection was documented in conventional LTα−/− mice (9).

Another study (42) utilizing bone marrow chimeras with different neo cassette-containing LTα-deficient mice as donors and RAG−/− mice as recipients claimed a TNF-independent protective role for soluble LTα in host protection against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Interestingly, peritoneal macrophages from this LTα-deficient strain were shown to have significantly reduced TNF production after activation with IFN-γ, and up to a 30-fold decrease after in vitro infection with T. gondii (44). Our data demonstrated severely impaired TNF production by neutrophils, monocytes, and to some extent mature macrophages in the conventional LTα KO mice and may call into question the “independent” protective role of soluble LTα in intracellular infections. These issues have to be resolved in the future.

Finally, we documented that T- and B-cell segregation, the size of splenic white pulp, and the extent of remaining BP-3-positive stromal cell network in spleens of novel LTαΔ/Δ mice resemble those seen in the spleens of LTβ KO mice (Fig. 5A, B, and C and data not shown). LTβ-, TNF-, and TNFRI-deficient mice have significantly reduced staining for BP-3 antigen in the spleen (36), suggesting the importance of both TNF and LTα1β2 ligands. Interestingly, BP-3-positive stromal cells are completely absent in LTβ/TNF double knockout mice, implying cooperation between TNF and LTα1β2 (Fig. 5B). It also implies that sLTα3→TNFRI signals were either not important or not sufficient to support the BP-3-positive stromal network in LTβ/TNF KO mice.

However, LTβR KO mice show a complete lack of BP-3 staining in spite of the fact that they normally express TNF, perhaps suggesting that an additional ligand for the LTβR, possibly LIGHT, may act in cooperation with TNF in supporting BP-3-positive stromal elements in splenic white pulp.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the role of LTα in the maintenance of at least some elements of splenic microarchitecture may be less significant than previously thought. By comparing splenic architecture in LTβ, LTβ/TNF (both neo free), and conventional LTα KO mice we have previously made conclusions about the contribution of TNF signaling in the maintenance of the spleen (26). We believe that this TNF-dependent component is at least partially impaired in conventional LTα KO mice.

In conclusion, the newly engineered neo-free LTα-deficient mice shed new light on the regulation of gene expression at the TNF/LT locus as well as on the contribution of individual TNF/LT family members to adaptive immune responses and lymphoid organ maintenance. This new mouse strain offers an important new tool for dissecting unique and overlapping functions of TNF and LTα in various pathophysiological situations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Shakhov, A. Tumanov, Y. Shebzukhov, and A. Hurwitz for fruitful discussion and critical remarks. We thank T. Banks and C. Ware for providing the alternative strain of LTα KO mice, Y. X. Fu for the LTβR-Ig protein, A. Garcia-Pineres for help with real-time PCR, and E. Southon and S. Reid for assistance in knockout mouse engineering. We are indebted to R. Matthai and K. Noer for cell sorting as well as to L. Drutskaya, S. Stull, and T. Stull for excellent technical support.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. NO1-CO-12400, and by a grant from the Russian Academy of Sciences (Molecular and Cell Biology). S.A.N. is an International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication no. 86-23, 1985).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, K., F. O. Yarovinsky, T. Murakami, A. N. Shakhov, A. V. Tumanov, D. Ito, L. N. Drutskaya, K. Pfeffer, D. V. Kuprash, K. L. Komschlies, and S. A. Nedospasov. 2003. Distinct contributions of TNF and LT cytokines to the development of dendritic cells in vitro and their recruitment in vivo. Blood 101:1477-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal, B. B. 2003. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:745-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexopoulou, L., M. Pasparakis, and G. Kollias. 1998. Complementation of lymphotoxin alpha knockout mice with tumor necrosis factor-expressing transgenes rectifies defective splenic structure and function. J. Exp. Med. 188:745-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alimzhanov, M. B., D. V. Kuprash, M. H. Kosco-Vilbois, A. Luz, R. L. Turetskaya, A. Tarakhovsky, K. Rajewsky, S. A. Nedospasov, and K. Pfeffer. 1997. Abnormal development of secondary lymphoid tissues in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 19;94:9302-9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baer, M., A. Dillner, R. C. Schwartz, C. Sedon, S. A. Nedospasov, and P. F. Johnston. 1998. TNF alpha transcription in macrophages is attenuated by an autocrine factor that preferentially induces NF-κB p50. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5678-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banks, T. A., B. T. Rouse, M. K. Kerley, P. J. Blair, V. L. Godfrey, N. A. Kuklin, D. M. Bouley, J. Thomas, S. Kanangat, and M. L. Mucenski. 1995. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. Effects on secondary lymphoid organ development and humoral immune responsiveness. J. Immunol. 155:1685-1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutler, B., I. W. Milsark, and A. C. Cerami. 1985. Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin. Science 229:869-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biragyn, A., and S. A. Nedospasov. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of TNF-alpha gene in the macrophage cell line ANA-1 is regulated at the level of transcription processivity. J. Immunol. 155:674-683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bopst, M., I. Garcia, R. Guler, M. L. Olleros, T. Rulicke, M. Muller, S. Wyss, K. Frei, M. Le Hir, and H. P. Eugster. 2001. Differential effects of TNF and LTalpha in the host defense against M. bovis BCG. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1935-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning, J. L., A. Ngam-ek, P. Lawton, J. DeMarinis, R. Tizard, E. P. Chow, C. Hession, B. O'Brine-Greco, S. F. Foley, and C. F. Ware. 1993. Lymphotoxin beta, a novel member of the TNF family that forms a heteromeric complex with lymphotoxin on the cell surface. Cell 72:847-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlan, J. W., and R. J. North. 1992. Roles of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors in survival: virulence factors distinct from listeriolysin are needed for the organism to survive an early neutrophil-mediated host defense mechanism. Infect. Immun. 60:951-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conlan, J. W., and R. J. North. 1994. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J. Exp. Med. 179:259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Togni, P., J. Goellner, N. H. Ruddle, P. R. Streeter, A. Fick, S. Mariathasan, S. C. Smith, R. Carlson, L. P. Shornick, J. Strauss-Schoenberger, J. H. Russell, R. Karr, and D. D. Chaplin. 1994. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science 264:703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn, J. L., and J. Chan. 2001. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:93-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flynn, J. L., M. M. Goldstein, J. Chan, K. J. Triebold, K. Pfeffer, C. J. Lowenstein, R. Schreiber, T. W. Mak, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity 2:561-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu, Y. X., and D. D. Chaplin. 1999. Development and maturation of secondary lymphoid tissues. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:399-433, 399-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu, Y. X., H. Molina, M. Matsumoto, G. Huang, J. Min, and D. D. Chaplin. 1997. Lymphotoxin-alpha (LTalpha) supports development of splenic follicular structure that is required for IgG responses. J. Exp. Med. 185:2111-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Futterer, A., K. Mink, A. Luz, M. H. Kosco-Vilbois, and K. Pfeffer. 1998. The lymphotoxin beta receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity 9:59-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galanos, C., M. A. Freudenberg, and W. Reutter. 1979. Galactosamine-induced sensitization to the lethal effects of endotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:5939-5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gommerman, J. L., and J. L. Browning. 2003. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:642-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grivennikov, S. I., A. V. Tumanov, D. J. Liepinsh, A. A. Kruglov, B. I. Marakusha, A. N. Shakhov, T. Murakami, L. N. Drutskaya, I. Forster, B. E. Clausen, L. Tessarollo, B. Ryffel, D. V. Kuprash, and S. A. Nedospasov. 2005. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of TNF produced by T cells and macrophages/neutrophils: protective and deleterious effects. Immunity. 22:93-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hehlgans, T., and K. Pfeffer. 2005. The intriguing biology of the tumour necrosis factor/tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily: players, rules and the games. Immunology 115:1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hestdal, K., F. W. Ruscetti, J. N. Ihle, S. E. Jacobsen, C. M. Dubois, W. C. Kopp, D. L. Longo, and J. R. Keller. 1991. Characterization and regulation of RB6-8C5 antigen expression on murine bone marrow cells. J. Immunol. 147:22-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holst, O., A. J. Ulmer, H. Brade, H. D. Flad, and E. T. Rietschel. 1996. Biochemistry and cell biology of bacterial endotoxins. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 16:83-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasaki, A., and R. Medzhitov. 2004. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:987-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuprash, D. V., M. B. Alimzhanov, A. V. Tumanov, A. O. Anderson, K. Pfeffer, and S. A. Nedospasov. 1999. TNF and lymphotoxin beta cooperate in the maintenance of secondary lymphoid tissue microarchitecture but not in the development of lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 163:6575-6580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuprash, D. V., M. B. Alimzhanov, A. V. Tumanov, S. I. Grivennikov, A. N. Shakhov, L. N. Drutskaya, M. W. Marino, R. L. Turetskaya, A. O. Anderson, K. Rajewsky, K. Pfeffer, and S. A. Nedospasov. 2002. Redundancy in tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and lymphotoxin (LT) signaling in vivo: mice with inactivation of the entire TNF/LT locus versus single-knockout mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8626-8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuprash, D. V., A. V. Tumanov, D. J. Liepinsh, E. P. Koroleva, M. S. Drutskaya, A. A. Kruglov, A. N. Shakhov, E. Southon, W. J. Murphy, L. Tessarollo, S. I. Grivennikov, and S. A. Nedospasov. 2005. Novel tumor necrosis factor-knockout mice that lack Peyer's patches. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:1592-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuprash, D. V., I. A. Udalova, R. L. Turetskaya, D. Kwiatkowski, N. R. Rice, and S. A. Nedospasov. 1999. Similarities and differences between human and murine TNF promoters in their response to lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 162:4045-4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagasse, E., and I. L. Weissman. 1996. Flow cytometric identification of murine neutrophils and monocytes. J. Immunol. Methods 197:139-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma, W., L. Tessarollo, S. B. Hong, M. Baba, E. Southon, T. C. Back, S. Spence, C. G. Lobe, N. Sharma, G. W. Maher, S. Pack, A. O. Vortmeyer, C. Guo, B. Zbar, and L. S. Schmidt. 2003. Hepatic vascular tumors, angiectasis in multiple organs, and impaired spermatogenesis in mice with conditional inactivation of the VHL gene. Cancer Res. 63:5320-5328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marino, M. W., A. Dunn, D. Grail, M. Inglese, Y. Noguchi, E. Richards, A. Jungbluth, H. Wada, M. Moore, B. Williamson, S. Basu, and L. J. Old. 1997. Characterization of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8093-8098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohler, K. M., D. S. Torrance, C. A. Smith, R. G. Goodwin, K. E. Stremler, V. P. Fung, H. Madani, and M. B. Widmer. 1993. Soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors are effective therapeutic agents in lethal endotoxemia and function simultaneously as both TNF carriers and TNF antagonists. J. Immunol. 151:1548-1561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller, U., C. V. Jongeneel, S. A. Nedospasov, K. Fisher Lindahl, and M. Steinmetz. 1987. Tumour necrosis factor and lymphotoxin genes map close to H-2D in the mouse major histocompatibility complex. Nature 325:265-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakane, A., T. Minagawa, and K. Kato. 1988. Endogenous tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) is essential to host resistance against Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect. Immun. 56:2563-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngo, V. N., H. Korner, M. D. Gunn, K. N. Schmidt, R. D. Sean, M. D. Cooper, J. L. Browning, J. D. Sedgwick, and J. G. Cyster. 1999. Lymphotoxin alpha/beta and tumor necrosis factor are required for stromal cell expression of homing chemokines in B and T cell areas of the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 189:403-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peschon, J. J., D. S. Torrance, K. L. Stocking, M. B. Glaccum, C. Otten, C. R. Willis, K. Charrier, P. J. Morrissey, C. B. Ware, and K. M. Mohler. 1998. TNF receptor-deficient mice reveal divergent roles for p55 and p75 in several models of inflammation. J. Immunol. 160:943-952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeffer, K., T. Matsuyama, T. M. Kundig, A. Wakeham, K. Kishihara, A. Shahinian, K. Wiegmann, P. S. Ohashi, M. Kronke, and T. W. Mak. 1993. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell 73:457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pham, C. T., D. M. MacIvor, B. A. Hug, J. W. Heusel, and T. J. Ley. 1996. Long-range disruption of gene expression by a selectable marker cassette. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13090-13095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pokholok, D. K., I. G. Maroulakou, D. V. Kuprash, M. B. Alimzhanov, S. V. Kozlov, T. I. Novobrantseva, R. L. Turetskaya, J. E. Green, and S. A. Nedospasov. 1995. Cloning and expression analysis of the murine lymphotoxin beta gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:674-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roach, D. R., H. Briscoe, B. Saunders, M. P. France, S. Riminton, and W. J. Britton. 2001. Secreted lymphotoxin-alpha is essential for the control of an intracellular bacterial infection. J. Exp. Med. 193:239-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roach, D. R., H. Briscoe, B. M. Saunders, and W. J. Britton. 2005. Independent protective effects for tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin alpha in the host response to Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect. Immun. 73:4787-4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scarff, K. L., K. S. Ung, J. Sun, and P. I. Bird. 2003. A retained selection cassette increases reporter gene expression without affecting tissue distribution in SPI3 knockout/GFP knock-in mice. Genesis 36:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schluter, D., L. Y. Kwok, S. Lutjen, S. Soltek, S. Hoffmann, H. Korner, and M. Deckert. 2003. Both lymphotoxin-alpha and TNF are crucial for control of Toxoplasma gondii in the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 170:6172-6182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sean, R. D., H. Korner, D. H. Strickland, F. A. Lemckert, J. D. Pollard, and J. D. Sedgwick. 1998. Challenging cytokine redundancy: inflammatory cell movement and clinical course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis are normal in lymphotoxin-deficient, but not tumor necrosis factor-deficient, mice. J. Exp. Med. 187:1517-1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shakhov, A. N., M. A. Collart, P. Vassalli, S. A. Nedospasov, and C. V. Jongeneel. 1990. Kappa B-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in primary macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 171:35-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsytsykova, A. V., and A. E. Goldfeld. 2002. Inducer-specific enhanceosome formation controls tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2620-2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Udalova, I. A., J. C. Knight, V. Vidal, S. A. Nedospasov, and D. Kwiatkowski. 1998. Complex NF-kappaB interactions at the distal tumor necrosis factor promoter region in human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21178-21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware, C. F. 2003. The TNF superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14:181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware, C. F. 2005. Network communications: lymphotoxins, LIGHT, and TNF. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:787-819, 787-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.