Abstract

Non-long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons are major components of the higher eukaryotic genome. Most of them have two open reading frames (ORFs): ORF2 encodes mainly the endonuclease and reverse transcriptase domains, but the functional features of ORF1 remain largely unknown. We used telomere-specific non-LTR retrotransposon SART1 in Bombyx mori and clarified essential roles of the ORF1 protein (ORF1p) in ribonucleoprotein (RNP) formation by novel approaches: in vitro reconstitution and in vivo/in vitro retrotransposition assays using the baculovirus expression system. Detailed mutation analyses showed that each of the three CCHC motifs at the ORF1 C terminus are essential for SART1 retrotransposition and are involved in packaging the SART1 mRNA specifically into RNP. We also demonstrated that amino acid residues 555 to 567 and 285 to 567 in the SART1 ORF1p are crucial for the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions, respectively. The loss of these domains abolishes protein-protein interaction, leading to SART1 retrotransposition deficiency. These data suggest that systematic formation of RNP composed of ORF1p, ORF2p, and mRNA is mainly mediated by ORF1p domains and is a common, essential step for many non-LTR retrotransposons encoding the two ORFs.

Retrotransposable elements are highly successful components in eukaryotic genomes. For instance, they occupy 42% of the human genome (16) and more than 20% of the silkworm genome (36). The retrotransposable elements can be classified into two subclasses. One is comprised of long terminal repeat (LTR)-type elements, which resemble the retrovirus both in structure and integration mechanisms. The other subclass is comprised of non-LTR-type elements, which are called long interspersed nuclear elements in mammals. The reverse transcription of LTR elements occurs in the cytoplasm, within virus-like particles (VLPs), which act as “protein shells” (26); in contrast, reverse transcription of non-LTR elements proceeds only in the nucleus using the target DNA as the primer. This process is called target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT) (17). The TPRT mechanism itself has been gradually clarified, but there is very limited information on how proteins and template mRNA of the non-LTR retrotransposons constitute the retrotransposable machinery, on how they migrate to the target site of the nucleus, and on what domains of non-LTR elements are involved in such processes.

Many non-LTR retrotransposons that belong to the recently branched type have two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1 and ORF2, whereas ancient-type non-LTR elements have only one ORF (19). In all non-LTR retrotransposons having two ORFs, ORF2 encodes an endonuclease domain, which cuts and determines the target site of integration, and a reverse transcriptase domain, which is responsible for reverse transcribing the RNA template. However, little is known about the structural and functional features of ORF1, except that they are essential for in vivo retrotransposition and that some CCHC-type zinc finger motifs (also called zinc knuckle motifs) located at the C terminus are conserved in many non-LTR elements. It is assumed by in vitro studies that the ORF1 protein (ORF1p) interacts with RNAs and is involved in protein multimerization (4, 15). In addition, some histological studies demonstrated colocalization of ORF1p and the ORF2 protein (ORF2p) (9) and of ORF1p and RNA (28). Based on these observations, it has been hypothesized that ORF1p, ORF2p, and RNA of recently branched-type non-LTR elements interact with each other to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. A recent report shows that the human long interspersed nuclear element 1 (L1) RNA and ORF1p form RNPs in vivo and that some ORF1 mutants have decreased RNP formation (15). However, we have no direct evidence in any non-LTR elements for ORF1p-ORF2p interaction, nor do we know what specific domains of ORF1 are responsible for RNP complex formation by ORF1p, ORF2p, and RNA.

Chromosomal ends of eukaryotes generally consist of telomeric repeats, which are synthesized by the reverse transcriptase activity of telomerase (2). Bombyx mori has a TTAGG telomeric repeat at the chromosomal ends, but its telomerase activity is very low. Since many copies of non-LTR retrotransposons such as TRAS1 and SART1 accumulate in the telomere regions of B. mori, it is hypothesized that they compensate the loss of telomere due to the low telomerase activity (6, 22, 27, 30). The complete unit of SART1 is 6.7 kb in length and terminates with a poly(A) stretch (Fig. 1A). There are 600 SART1 copies in the silkworm haploid genome, and most of them are completely conserved in structure without 5′ truncation (30), although many non-LTR retrotransposons are 5′ truncated due to incomplete reverse transcription (8). And while expression of retroelements is usually suppressed in general, SART1 mRNA is transcribed abundantly and is detected easily by Northern hybridization (31). These data suggest that the telomere-specific SART1 has a high retrotransposable activity and is a good model to study the retrotransposition mechanisms of non-LTR retrotransposons. Recently, we established a baculovirus-mediated retrotransposition system in which the specific integration of SART1 into the telomeric repeats of the host cells could be easily detected (32). Using this system, we have shown that ORF1p of SART1 encodes a novel nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a putative telomere targeting domain, both of which are essential for in vivo retrotransposition (20). We have also recently found that SART1 can retrotranspose by trans complementation when the ORF1 construct and the ORF2 plus 3′ untranslated region (ORF2/3′ UTR) construct are coexpressed in vivo (13), indicating that ORF1p can recognize and interact in trans with ORF2p and SART1 mRNA in the cells.

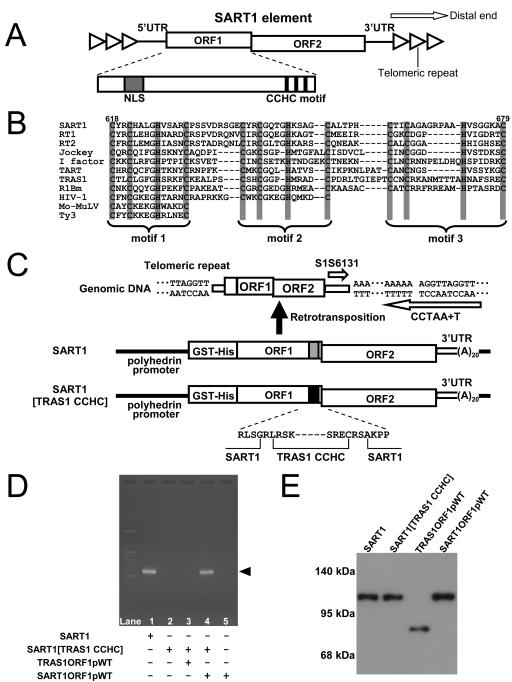

FIG. 1.

Conserved CCHC motifs in retroelements. (A) Schematic structure of SART1. Open triangles and boxes represent the telomeric repeats and ORFs of the SART1 element, respectively. SART1 ORF1 has the NLS shown by the gray box at the N terminus and has three CCHC motifs indicated by three vertical lines at the C terminus. SART1 inserts in the same orientation with TTAGG telomeric repeats. (B) Conservation of CCHC motifs among retroelements. Amino acid alignments of CCHC motifs from ORF1p proteins of non-LTR retrotransposon, Gag proteins of retroviruses, and LTR retrotransposon are shown in parallel. SART1, RT1, RT2, jockey, I factor, TART, TRAS1, and R1Bm are non-LTR retrotransposons. HIV-1 and Mo-MuLV belong to retroviruses. Ty3 is an LTR retrotransposon. Numbers at the top of the sequences indicate amino acid positions of SART1 ORF1. (C) In vivo retrotransposition assay for SART1/TRAS1 chimeric retrotransposon. The WT SART1 element was fused to GST-(His)6 tag and expressed under the polyhedrin promoter of baculovirus AcNPV. Total DNAs of Sf9 cells were purified at 72 h postinfection of the respective AcNPV-retrotransposon constructs, and PCR amplification was performed with two primers, shown by open arrows, between the 3′ UTR of retrotransposed SART1 and the telomeric repeats in the Sf9 host genome. Gray and black boxes show the C terminal region containing three CCHC motifs of SART1 and TRAS1, respectively. The N- and C-terminal boundaries in the TRAS1 CCHC region of the chimeric retrotransposon are shown at the bottom. (D) The results of in vivo retrotransposition assay. The PCR bands of approximately 600 bp in length (arrowhead) represent the exact retrotransposition. The ORF1 portion of TRAS1 and SART1 in AcNPV was coinfected with SART1 constructs to test the trans complementation ability (lanes 3 and 4). (E) Immunoblot detection of GST-His-tagged ORF1 proteins. Total proteins from Sf9 cells infected with each recombinant AcNPV construct were analyzed by immunoblot detection with anti-His antibody to detect His-tagged proteins. Positions of molecular size markers are shown on the left.

In most retroelements including retroviruses, ORF1 (or Gag) proteins retain their remarkable structures of one to three zinc finger motifs generally represented by CX2CX4HX4C (CCHC motif; X indicates spacing) (1). The spacing of the third motif in most and of the second motif in some non-LTR retrotransposons is less conserved. This motif is rarely observed in other cellular proteins, and thus the CCHC motif is peculiar to retroelements. In retroviruses, the CCHC motifs are involved in binding to the retroviral RNA (5), in nucleic acid chaperone activity (35), and in multimerization of Gag proteins (33). SART1 ORF1 has three CCHC motifs at the C terminus (Fig. 1A). A point mutation of the first CCHC motif causes a defect of the in vivo retrotransposition of SART1 (32), which is the only direct evidence of the involvement of the CCHC motif in the retrotransposition activity of non-LTR retrotransposons.

The aim of this study is to clarify the functional roles of the ORF1 protein of SART1, especially in RNP complex formation, and to identify the essential ORF1 domains involved in this process. By in vivo reconstitution of SART1 RNP complex in Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (Sf9) cells using the baculovirus expression system, we demonstrate that the SART1 RNP complex contains the multimerized ORF1p, ORF2p, and SART1 mRNA. We found that several regions of ORF1 protein near the C terminus are essential for interactions between ORF1p and ORF1p and between ORF1p and ORF2p. In particular, 13 amino acids, VARIGECPPDIVK, which are residues 555 to 567, are crucial to both interactions. In addition, we found that all three CCHC motifs are involved in the specific packaging of SART1 mRNA into the RNP complex. We propose that the C-terminal area of the ORF1 protein in SART1 is responsible for RNP complex formation through ORF1p-ORF1p, ORF1p-ORF2p, and ORF1p-mRNA interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

For plasmid construction, SART1 DNA was amplified by PCR from BS103 or from SART1WT-pAcGHLTB (20) with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Primers used for the plasmid construction are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Plasmid expressing HA-tagged protein.

The hemagglutinin (HA)-SART1ORF2/3′ UTR plasmid is the same as construct IV in Kojima et al., and the construction of the vector lacking a glutathione transferase (GST)-His tag, named pAcLTB, was also described previously (13). HA-SART1ORF1pWT was constructed as follows. The portion of SART1 ORF1 was amplified by PCR from plasmid S1ORF1pWT with the primers S1S880NdeI and pAcBA3106. The PCR products were subcloned between the NdeI and BamHI sites of pGADT7 (Clontech). The region including SARTORF1 and the HA tag was amplified by PCR using the primers T7 and S1A3029NotI. The PCR products were subcloned between the NcoI and NotI sites of the vector lacking GST-His tag (pAcLTB).

Plasmid expressing partial SART1 ORF1.

We constructed the vector lacking a GST tag from the plasmid pAcGHLTB (Pharmingen) because the GST tag sometimes bound to nonspecific nucleic acids and proteins. The whole pAcGHLTB plasmid except the GST tag sequence was amplified by inverse PCR using the 5′ phosphorylated primers pAcBA2214 and pAcBS2863. Phosphorylated primers were made by T4 polynucleotide kinase (TaKaRa) and ATP (Roche). The PCR products were self-ligated, and the resulting plasmid was named pAcHisB. Partial sequences of SART1 were subcloned between the NcoI and NotI sites of pAcHisB.

Mutation introduction.

Point mutations were introduced with pairs of primers using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The deletion mutants were constructed by inverse PCR and self-ligation using the 5′ phosphorylated primers as described above. SART1-pAcGHLTB containing the TRAS1 ORF1 C terminus was constructed as follows. First, the NotI-BglII region of SART1WT-pAcGHLTB was removed by NotI and BglII digestion, T4 DNA polymerase treatment, and self-ligation. Second, the whole region of SART1-pAcGHLTB except the ORF1 C terminus was amplified by inverse PCR with the 5′ phosphorylated primers S1A2505NotI and S1S2917BglII. The amplified product was self-ligated. Third, the TRAS1 ORF1 C terminus was amplified with T1S3359NotI and T1A3761BglII and cloned between the NotI and BglII sites of that plasmid.

Target plasmid for in vitro TPRT assay.

To obtain Bombyx telomeric repeats (TTAGG/CCTAA)n, PCR amplification was carried out using the primers (CCTAA)6 and (TTAGG)6 without a template (12). The PCR products were cloned by the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega), and a plasmid including (TTAGG)25 was isolated. The (TTAGG)25 sequence was subcloned to pBluescript II SK(+) by EcoRI.

Recombinant AcNPV generation.

Recombinant Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcNPV) generation was carried out according to the BaculoGold (Pharmingen) instructions and a previous study (32).

In vivo retrotransposition assay.

The in vivo retrotransposition assay was performed as described previously by Takahashi and Fujiwara (32). Primers S1S6131 and CCTAA+T (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used for PCR amplification of the 3′ junction of retrotransposed SART1. The PCR signals were quantified using the NIH program Image J (see Fig. 2D).

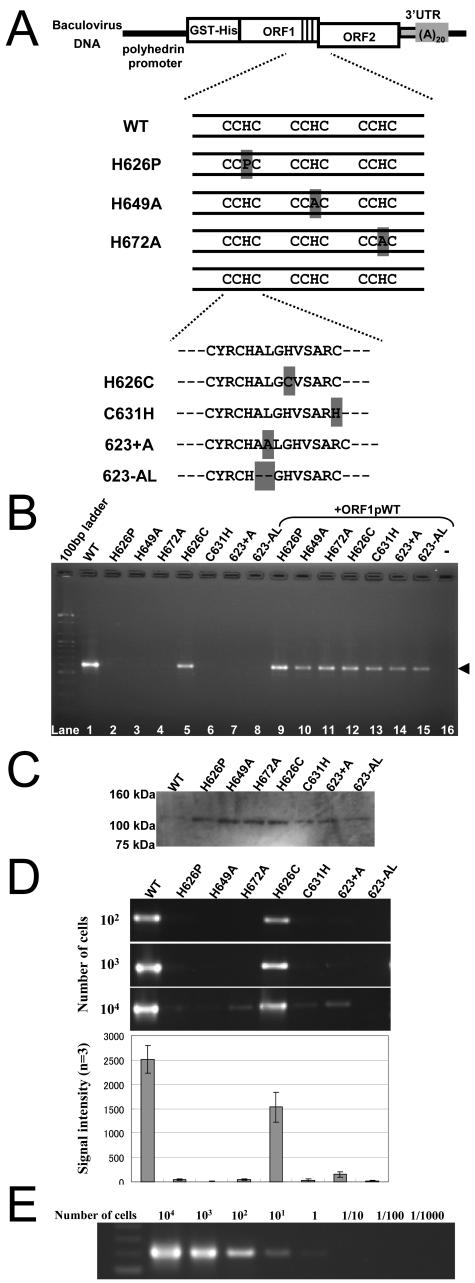

FIG. 2.

Requirement of the CCHC motifs of ORF1 for SART1 retrotransposition in vivo. (A) Constructs of various SART1 CCHC motif mutants. In constructs H626P, H649A, H672A, H626C, and C631H, amino acids shaded in gray indicate the substitutive mutation site. In 623+A, an additional alanine is inserted between 623-Ala and 624-Leu of the first CCHC motif, and in 623-AL, two amino acids, 623-Ala and 624-Leu, are deleted. (B) Results of the in vivo retrotransposition assay. A 100-bp DNA ladder was run in the left-hand lane. The PCR bands of approximately 600 bp in length (arrowhead; lanes 1 and 5) represent the exact retrotransposition. In lanes 9 to 16, AcNPV expressing the full-length SART1 ORF1p (ORF1pWT) was coinfected simultaneously and rescued the retrotransposition ability. (C) Immunoblot detection of ORF1p shown in panel B. GST-His-tagged ORF1 proteins were detected with anti-His antibody. Numbers on the left indicate the size of molecular weight markers. (D) Detection of extremely low retrotransposition of CCHC mutants. The amount of the genomic DNA used as a PCR template is roughly equivalent to the number of cells shown on the left. The signals from experiments when 104 cells were used as PCR templates were quantified using Image J; results are shown as signal intensity. (E) SART1 WT retrotransposition in the diluted series of templates. In vivo retrotransposition assay of WT was carried out using a 10-fold dilution series of PCR templates. The amount of PCR template is roughly equivalent to the number of cells shown at the top.

Immunoblot detection of fusion protein.

The fusion protein was detected by immunoblot analysis as previously described (20). Protein samples were prepared from the purified SART1 complex (eluate fraction) or from crude supernatant of Sf9 cells at 72 h after the AcNPV infection (extract fraction). Anti-His antibody (Amersham) or anti-HA antibody (Roche) was used as a primary antibody. The blots were developed using ECL Plus (Amersham) for SART1 ORF1p and with ECL Advance (Amersham) for SART1 ORF2p.

Purification of SART1 complex.

Sf9 cells were infected with His6-SART1 containing AcNPV at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0 for 72 h, pelleted by centrifugation, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were resuspended in ice-cold HG500 (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, 500 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 50 mM imidazole, 1 mM mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% Triton X-100) buffer and sonicated slightly. The debris was pelleted at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the lysate was bound to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose (QIAGEN), preequilibrated with the HG500 buffer, for 2 h at 4°C. The resin was washed with 500 volumes of HG500 buffer at 4°C and eluted with 5 volumes of HG500 buffer plus 250 mM imidazole for 30 min at 4°C. For in vitro rescue experiments, wild-type (WT) SART1 ORF1p was prepared in parallel according to the same procedure (see Fig. 3C). Every eluate except the mock, in which only His tag was expressed, was adjusted to 10 ng/μl with HG500 buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluate was stored at −80°C in 10-μl aliquots.

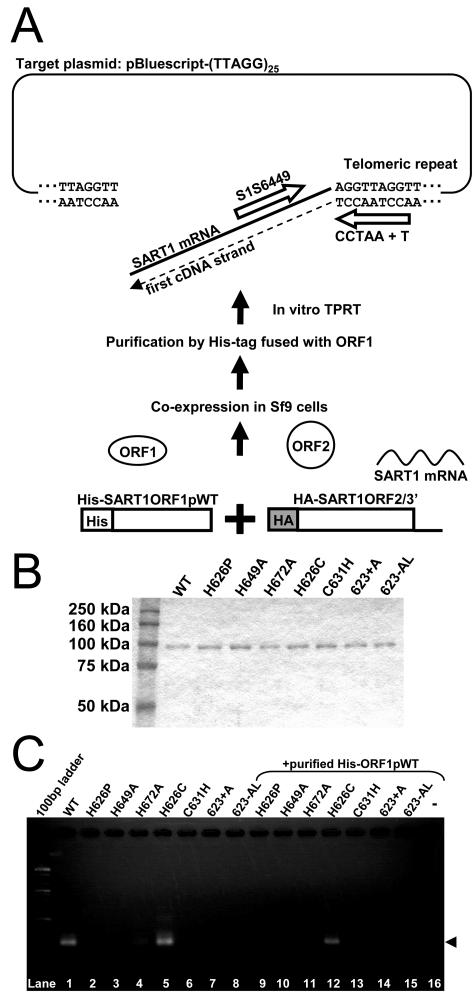

FIG. 3.

Requirement of the CCHC motifs of ORF1 for in vitro TPRT activity of SART1. (A) Outline of the in vitro TPRT assay. His-tagged SART1 ORF1 and HA-tagged SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR were coexpressed in Sf9 cells using AcNPVs (bottom to top). The SART1 complex was purified by Ni-NTA agarose, which has a specific affinity with His tag. When purified SART1 complex, pBluescript-(TTAGG)25 target plasmid, and dNTP were incubated for reaction in vitro, the first cDNA strand was synthesized from the nicked site of the bottom strand of the telomeric repeats, which were digested by the endonuclease domain of SART1. The reverse transcribed products were detected by PCR with primers S1S6449 and CCTAA+T (open arrows). (B) The Coomassie brilliant blue staining after SDS-PAGE of the purified SART1 complex used in the in vitro TPRT assay. The protein molecular size marker was run in the left-hand lane. (C) Results of in vitro TPRT assay. The boundaries between SART1 3′ ends and the telomeric repeats were amplified by PCR using the primer set S1S6449 and CCTAA+T. A 100-bp DNA ladder was run in the left-hand lane. The PCR band of about 300 bp in length (arrowhead) represents the exact TPRT product (lanes 1, 5, and 12) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In lanes 9 to 16, His-tagged SAR1ORF1p purified in parallel was simultaneously added into the reaction component of in vitro TPRT.

In vitro TPRT reaction.

The purified eluate was directly used for the in vitro TPRT reaction. The in vitro TPRT reaction buffer included 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 50 ng of target plasmid containing the Bombyx telomeric repeats. Ten nanograms of SART1 RNP was added to 40 μl of buffer and was incubated at 30°C for 60 min. In the in vitro rescue experiment (shown in Fig. 3C) 50 ng of WT SART1 ORF1p, which was purified in parallel, was simultaneously added to the buffer. After heat inactivation at 80°C for 20 min, 1 μl of the reaction mixture was amplified by PCR for 35 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with an initial denaturation at 96°C for 2 min and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR mixtures contained 200 μM concentrations of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 U of Ex-Taq (TaKaRa), and 0.5 μM concentrations of each primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Glycerol gradient sedimentation.

Purified SART1 complex was overlaid onto 3.3 ml of 10 to 40% glycerol gradient in the HG500 buffer. Centrifugation was carried out using a swing rotor P55ST2 (Hitachi) for 16 h at 40,000 rpm at 4°C. Thyroglobulin (670 kDa; SIGMA) and BSA (67 kDa; Biomedical Technologies, Inc.) were used as protein molecular weight standards. A total of 300 μl of each fraction was collected from the bottom and stored at −80°C. The fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on an 8% gel, followed by electrophoretic transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Pall Corp.) and immunoblot detection using anti-His antibody (Amersham). The absence and presence of SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA (SART1 residues 6131 to 6702) in each fraction were analyzed by subsequent reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from the purified SART1 RNP and the glycerol gradient fraction by a TRI Reagent LS kit (SIGMA). The RNA mixture was treated by DNase I (TaKaRa) to exclude DNA contamination. Components of the reverse transcriptase reaction mixture included the following: 0.1 μM pd(N)6 primer, 0.5 mM concentrations of each dNTP, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, and 3 mM MgCl2. One microliter of RNA solution was added to the buffer and denatured at 65°C for 5 min and then incubated in the presence of 100 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 37°C for 50 min. After heat inactivation at 70°C for 15 min, 1 μl of the resulting mixture was amplified by PCR. The PCR assays were conducted using the Ex-Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa) with the respective primer sets (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR mixture was denatured at 96°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min.

RESULTS

SART1 retrotransposition requires its own ORF1 C terminus, including CCHC motifs.

There are three CCHC motifs (zinc knuckles) at the C terminus of SART1 ORF1 (Fig. 1A). The CX2CX4HX4C structure is peculiar and is conserved among Gag and ORF1 proteins in most retroelements. When CX2CX3-9HX4-6C was defined as a CCHC motif, it was also reported in the ORF1 proteins of Tad, R1, LOA, I, and jockey clade non-LTR retrotransposons (19), which has evolved recently. However, we could not find them in the older clades (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that the CCHC motifs were obtained recently after branching of non-LTR elements encoding two ORFs. We compared the structures of the CCHC motifs in ORF1p of the non-LTR elements (SART1, RT1, RT2, jockey, I factor, TART, TRAS1, and R1Bm), of the Gag proteins of retroviruses (human immunodeficiency virus type 1 [HIV-1], Mo-MuLV), and of LTR-retrotransposon (Ty3) (Fig. 1B). Non-LTR elements have three CCHC motifs, whereas retrovirus and LTR elements have one or two motifs. Although the spacing of motif 1 is the same in all retroelements, that of motifs 2 and 3 is less conserved in non-LTR retrotransposons.

We tried to determine whether the three CCHC motifs between SART1 and TRAS1, the telomere-specific non-LTR retrotransposons in B. mori, can be exchanged functionally. We constructed a chimeric SART1-TRAS1 CCHC motif element by replacing the SART1 C terminus, which includes three CCHC motifs, with TRAS1 (Fig. 1C). In all constructs, the N terminus of ORF1 was fused with the GST-His6 tag. From previous studies, it is shown that SART1 expressed under the polyhedrin promoter of AcNPV in Sf9 cells transposes into the specific site at telomeric repeats (TTAGG)n, which can be detected by PCR using a specific primer set, S1S6131 and CCTAA+T (32). The WT SART1 actively retrotransposed 72 h postinfection (Fig. 1D, lane 1), but the chimeric SART1 element did not (lane 2). Coexpression of the SART1 ORF1p rescued the retrotransposition of the chimeric construct by trans complementation (lane 4), but the TRAS1 ORF1p did not (lane 3). We confirmed the expression of proteins in all constructs by immunoblot detection (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that, for retrotransposition, SART1 requires its own CCHC motifs in ORF1 and that they cannot be replaced by motifs of other non-LTR retrotransposons.

Any CCHC motifs of ORF1 are essential for SART1 retrotransposition in vivo.

To further examine whether three CCHC motifs are crucial for SART1 retrotransposition, we generated a series of SART1 constructs containing point mutations in every motif (Fig. 2A). H626P (626-His→Pro at motif 1), H649A (649-His→Ala at motif 2), and H672A (672-His→Ala at motif 3) were assumed as severe mutants for the zinc finger function. We changed the CCHC motif at motif 1 to the CCCC type in H626C (626-His→Cys) and to the CCHH type in C631H (631-Cys→His). Also, to understand the role of spacing in the CX2CX4HX4C (X indicates spacing) sequence, we changed the spacing in motif 1. The construct 623+A had one additional alanine residue between 623-Ala and 624-Leu, and the construct 623-AL lost the residues 623-Ala and 624-Leu.

Although the retrotransposition of WT SART1 occurred actively, H626P, H649A, and H672A did not show a significant PCR band (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 4). The expression of proteins in the three constructs at expected sizes was confirmed by immunoblot detection (Fig. 2C). The retrotransposition activities in the three mutants were rescued by coinfection of the WT SART1 ORF1p construct by trans complementation (Fig. 2B, lanes 9 to 11). These results indicate that all three CCHC motifs of ORF1 are necessary for retrotransposition of SART1 in vivo. Interestingly, the CCCC mutant H626C retrotransposed into telomeric repeats, whereas C631H (CCHH mutant), 623+A, and 623-AL could not (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 to 8). trans Complementation with normal ORF1p expression also rescued the retrotransposition activity (Fig. 2B, lanes 13 to 15). These results indicate that both the CCHC sequence itself and the spacing of amino acids are essential and that the CCCC type, but not the CCHH type, exhibits equivalent function of with the CCHC type, at least for motif 1 in the SART1 retrotransposition.

We wondered if the CCHC motif mutants had completely lost the retrotransposition activity by just a single amino acid mutation. To quantitatively evaluate retrotransposition activity, we changed the amount of genomic DNA used for the PCR assays. When we increased the amount of template genomic DNA by 10-fold (to calculate roughly, genomic DNAs extracted from 104 cells), we detected very weak signals for retrotransposition from every mutant (Fig. 2D, 104). Next, we analyzed the retrotransposition activity of WT using a 10-fold dilution series of template DNA (Fig. 2E) (roughly calculating, DNA was extracted from 104 to 1/1,000 cells). The retrotransposition of WT was still detected when the template was diluted to 1/1,000 of the original PCR condition (DNAs roughly equivalent to 1 cell). These results indicate that the CCHC mutants do not completely lose retrotransposition activities, but they are extremely suppressed compared to WT (roughly calculating, the CCHC mutants have only 1/1,000 the activity of the WT) (Fig. 2D). We previously reported that the deletion of the N-terminal NLS (residues 1 to 142 [Δ1-142]) or the central basic domain (Δ440-447) of ORF1, which controls cellular localization, strongly decreases the retrotransposition activity of SART1. However, these mutants retain very low activity under the same experimental condition of the WT, unlike CCHC motif mutants (20). These data suggest that the CCHC motifs of ORF1 are indispensable to SART1 retrotransposition and that mutations to them are critical.

CCHC-mutated SART1 complexes reconstituted in vivo cannot be rescued in vitro.

We next questioned how the CCHC motif works in the processes of SART1 retrotransposition. Because the CCHC motifs in retroviruses are thought to be involved in the complex formation of viral proteins and genomic RNAs (5, 33), we next studied the complex formation through the SART1 CCHC motifs by a new in vitro retrotransposition analysis. We infected Sf9 cells with full-length WT SART1-AcNPV and purified the ORF1 protein using a His tag. When we incubated this purified “ORF1” protein with plasmid including telomeric repeat sequences, it showed TPRT activity without the addition of template RNA or ORF2 protein. Therefore, we assumed that this “purified” ORF1p fraction involves the ORF2p and SART1 mRNA as a putative RNP complex, which is retained even during the elution steps in vitro.

To verify this assumption, we coinfected two AcNPV constructs, SART1 ORF1 (His tag fused) and SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR (HA tag fused), into the Sf9 cells, purified the ORF1p fraction by Ni-NTA agarose, and tested whether it included ORF2p and ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA using an in vitro retrotransposition assay (summarized in Fig. 3A). The eluted fraction showed only one strong band corresponding to the SART1 ORF1p by Coomassie brilliant blue staining after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B). After the eluted fraction was incubated with the plasmid containing Bombyx telomeric repeats and amplified by PCR with the primer set S1S6449 and CCTAA+T, we detected a band representing retrotransposition at the expected size in the WT ORF1 and H626C (CCCC mutant) ORF1 constructs (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 5, arrowhead) but not in any other CCHC motif mutants (lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8). These results are consistent with those of the in vivo retrotransposition assay (Fig. 2). We further cloned and sequenced the PCR products (Fig. 3C, lane 1, WT, and lane 4, CCCC-type mutant) (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) and found that only ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA (not ORF1 mRNA) was reverse transcribed and inserted specifically into various sites in telomeric repeats of the target plasmid (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). This result indicates that ORF1p of SART1 interacts with the ORF2p/3′ UTR mRNA to form the retrotransposable machinery and that the CCHC motifs are involved in some processes in these interactions.

Interestingly, the in vitro addition of purified WT ORF1p into the reaction buffer did not rescue the TPRT activity of the CCHC motif mutants (Fig. 3C, lanes 9 to 15), which is not consistent with the above results in coexpression in vivo (Fig. 2C, lanes 9 to 15). This result implies that the involvement of host factors in the cell or de novo complex formation immediately after translation is essential to generate the intact RNP unit of SART1.

The retrotransposition activity of H626C (lane 5) somewhat decreased when His-tagged ORF1p WT was added (Fig. 3C, lane 12). We have data indicating that the SART1 ORF1p binds to telomeric repeats (T. Matsumoto and H. Fujiwara, unpublished data). Thus, in the case of in vitro assays, excess WT ORF1p may bind to and cover telomeric repeats of the target plasmid and inhibit retrotransposition.

The specific domain but not the CCHC motifs in SART1 ORF1 directs the ORF1p-ORF1p interaction.

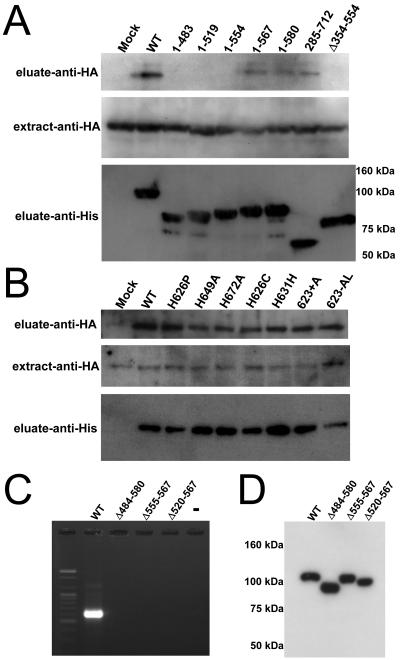

To directly analyze the protein-protein interaction with SART1 ORF1p, we used the baculovirus expression system to coexpress various ORF1p constructs fused with His tag and ORF1p (Fig. 4) or ORF2p (see Fig. 5) fused with HA tag and examined their interactions in the Sf9 cells. WT or mutated ORF1 proteins with a His tag at their N termini and a WT ORF1p with an HA tag at its N terminus were coexpressed (extract fraction) and purified by Ni-NTA agarose (eluate fraction) (Fig. 4A). HA-tagged ORF1p was detected by immunoblot analysis in the His-tag-based eluate fraction of WT ORF1p, which we had expected it to form protein complexes with (Fig. 4B, eluate-anti-HA, WT). This result indicates that the His-tagged WT SART1 ORF1p coprecipitated HA-tagged SART1 ORF1p through some form of interaction. In contrast, the mock construct expressing only the His tag did not coprecipitate HA-ORF1p (Fig. 4B, eluate-anti-HA, Mock).

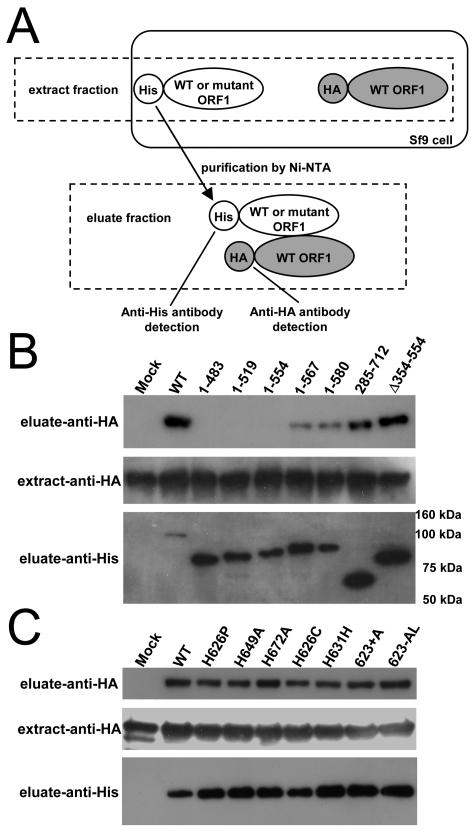

FIG. 4.

In vivo reconstitution analysis for detecting SART1 ORF1p-ORF1p interaction. (A) Scheme of ORF1-ORF1 protein interaction assay. His-tagged WT/mutant ORF1p and HA-tagged WT ORF1p were expressed simultaneously in the Sf9 cells by coinfection of AcNPVs. Expressed proteins are expected to bind with each other and form the protein complex in vivo if they originally interact. After purification by His tag that is fused with ORF1p, the complexes were submitted to immunoblot detection by anti-His and anti-HA antibody. Crude extracts from Sf9 expressing proteins and purification products from the extracts using His tag are described as “extract fraction” and “eluate fraction,” respectively, in this paper. (B) Immunoblot detection of HA-tagged ORF1p in the reconstituted SART1 complex purified with His-tagged deletion mutants of SART1 ORF1. Each construct is shown in Fig. 8. Antibodies are indicated at left. Molecular sizes are indicated on the right of the bottom photo. (C) The ORF1p-ORF1p interaction in various CCHC motif mutants. HA-tagged ORF1p was detected in every SART1 complex with a CCHC mutation. Antibodies are indicated at left.

FIG. 5.

In vivo reconstitution analysis of the ORF1p-ORF2p interaction of SART1. (A) Immunoblot detection of HA-tagged ORF2p in the in vivo reconstituted SART1 complex, which was purified with His-tagged WT or deletion mutants of SART1 ORF1. Antibodies are indicated at left. Molecular sizes are indicated at right on the bottom blot. (B) The ORF1p-ORF2p interaction in various CCHC motif mutants. Antibodies are indicated at left. (C) In vivo retrotransposition assay of SART1 deleted small parts of ORF1, which are essential for interaction between the ORF proteins. The assay was performed as described for Fig. 2. (D) In vivo protein expressions of ORF1p constructs shown in panel C. Protein molecular size markers are shown on the left.

To determine the ORF1p domain involved in the ORF1p-ORF1p interaction, we generated His-tagged ORF1 mutants by deleting various large areas of SART1 ORF1 (Fig. 4B; see also schematic illustrations in Fig. 8A). His-tagged ORF1p constructs with deletions in C termini such as construct 1-483 (residues 484 to 712 deleted), 1-519 (520 to 712 deleted), and 1-554 (555 to 712 deleted) did not coprecipitate the HA-tagged ORF1p. In contrast, in constructs 1-567 (residues 568 to 712 deleted) and 1-580 (581 to 712 deleted), a weak band of coprecipitated HA-tagged ORF1p was observed. This indicates that C-terminal regions, especially residues 555 to 567, are involved in the ORF1-ORF1 protein interaction in SART1. Consistent with this conclusion, an N-terminal-deleted mutant construct 285-712 (residues 1 to 284 deleted) and a central region deleted mutant Δ354-554 (354 to 554 deleted) showed strong signals similar to those of the WT. The HA-tagged ORF1p constructs were almost equally expressed (Fig. 4B, extract-anti-HA) and various His-tagged ORF1p constructs were recovered to a similar extent (Fig. 4B, eluate-anti-His) (SDS-PAGE results not shown).

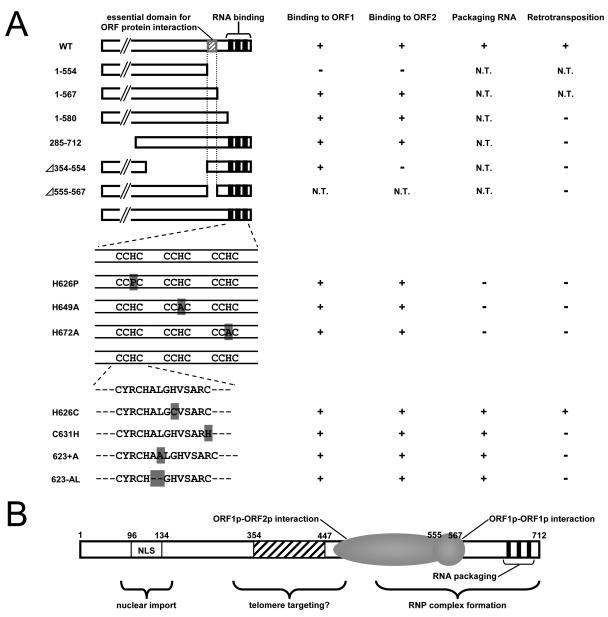

FIG. 8.

Summary of ORF1 mutant phenotypes. (A) SART1 ORF1 constructs in this study are shown on the left. Partial ORF1 mutants are indicated in the upper half of the panel. ORF1 constructs containing mutations in the CCHC motif are shown in the lower half. Bold lines represent CCHC motifs. Amino acids shaded in gray represent the same mutation as shown in Fig. 2A. SART1 ORF1 abilities, which are ORF1p-ORF1p binding, ORF1p-ORF2p binding, RNA packaging, and retrotransposition, are indicated on the right. To simplify the figure, extremely weak retrotransposition is shown as minus. NT, not tested. (B) Functional map of SART1 ORF1. Vertical lines at the C terminus indicate the CCHC motifs that are involved in RNA packaging. The ORF1p-ORF1p (residues 555 to 567) and ORF1p-ORF2p (residues 285 to 567) interaction domains are overlapped just before the CCHC motifs. SART1 ORF1 contains an NLS at the N terminus. The hatched box indicates the domain essential for the nuclear dotted localization, a possible telomere targeting domain.

We performed the same assay for various CCHC-mutated His-tagged ORF1p (Fig. 4C) constructs because the CCHC motifs are involved in Gag protein multimerization in retroviruses (33). CCHC-mutated ORF1p bound to HA-tagged ORF1p similarly to the WT construct (Fig. 4C, eluate-anti-HA), indicating that the CCHC motifs of ORF1p in SART1 are not involved in the ORF1p-ORF1p interaction.

SART1 ORF1p binds directly to ORF2p.

Using a similar assay, we next examined whether the His-tagged ORF1p also interacts with the HA-tagged ORF2p of SART1 (Fig. 5). His-tagged ORF1p and HA-tagged ORF2p constructs were coexpressed in Sf9 cells in the baculovirus expression system (extract fraction), and the extract was purified by Ni-NTA agarose (eluate fraction). In the eluate fraction, the anti-HA antibody detected a strong band representing the HA-tagged ORF2p, which was trapped by the WT His-tagged ORF1p. In contrast, no HA-tagged ORF2p coprecipitated with the His-tagged mock protein (Fig. 5A, eluate-anti-HA, WT and Mock). We also observed a clear band of HA-tagged ORF2p showing interaction with three His-tagged ORF1p constructs, 1-567 (residues 568 to 712 deleted), 1-580 (581 to 712 deleted), and 285-712 (1 to 284 deleted) but not in constructs 1-483, 1-519, and 1-554, which lacked a large C-terminal region of ORF1p, nor in Δ354-554, the deleted central region (Fig. 5A, eluate-anti-HA). Interestingly, the CCHC motif mutants of ORF1p interacted with ORF2p in the same way as WT-ORF1p (Fig. 5B, eluate-anti-HA). In all cases, HA-tagged ORF2p was normally expressed (extract-anti-HA), and His-tagged ORF1p was purified to a similar extent (Fig. 5, eluate-anti-His) (SDS-PAGE results not shown). Based on these results, we conclude that (i) residues 555 to 567 of ORF1p are involved in the ORF1p-ORF1p interaction and are essential for the ORF1p-ORF2p interaction, (ii) that the ORF1p-ORF2p interaction requires another domain within residues 285 to 554 of ORF1p, and (iii) that CCHC motifs are not involved in the ORF1p-ORF1p or ORF1p-ORF2p interactions.

We performed an in vivo retrotransposition assay on SART1 constructs lacking the ORF1 regions implicated in the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions discussed earlier (Fig. 5C). When the WT SART1 ORF1 and ORF2/3′ UTR were coexpressed in Sf9 cells, we observed a strong PCR band representing SART1 (precisely mRNA for ORF2/3′ UTR) retrotransposed to the telomere of the genome by trans action between ORF1p, ORF2p, and SART1 mRNA (13) (Fig. 5C, WT). When three ORF1 constructs Δ484-580, Δ555-567, and Δ520-580, which lacked the regions involved in the protein interactions, were coexpressed with ORF2/3′ UTR, no bands for retrotransposition were observed (Fig. 5C), although the mutated constructs expressed ORF1p to the same extent as the WT construct (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions are conducted via specific domains of ORF1p and are essential for the retrotransposition activity of SART1.

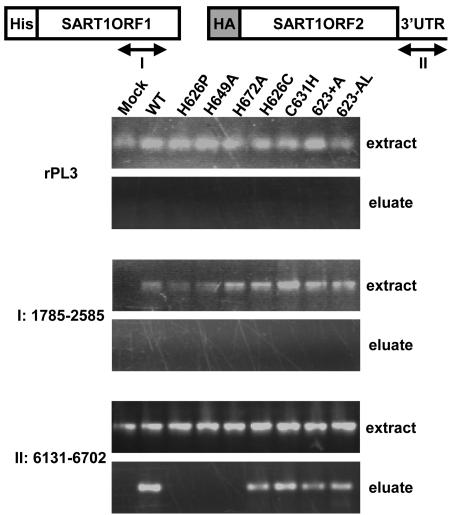

CCHC motifs of ORF1 play a role in the packaging of SART1 RNA into the RNP complex.

Our data show that the three CCHC motifs are essential for the SART1 retrotransposition but are not involved in the interactions between ORF proteins. Consequently, we tested the involvement of CCHC motifs in the ORF1p-RNA interaction, because in vitro TPRT (Fig. 3) showed that the SART1 complex included its own mRNA autonomously, without the addition of an extra RNA template. In a system similar to that shown in Fig. 3, His-tagged ORF1p and HA-tagged ORF2/3′ UTR were coexpressed in Sf9 cells in the baculovirus expression system (extract fraction), and the protein complex was purified by Ni-NTA agarose (eluate fraction) (Fig. 6). Using RT-PCR with three primer sets, we detected mRNAs for S. frugiperda ribosomal protein L3 gene (rPL3), ORF1 (the region of residues 1785 to 2585), and ORF2/3′ UTR (the 3′ UTR region of residues 6131 to 6702) in the extract fraction of Sf9 cells. However, in the eluate fraction purified by His-tagged WT ORF1p, we detected the ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA (Fig. 6, II, WT) but not the ORF1p and rPL3 mRNAs (Fig. 6, rPL3 and I, WT). This result indicates that mRNA of SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR but not of ORF1 is recognized by SART1 ORF1p and packaged into the ORF1p-ORF2p complex, which is consistent with the trans complemented retrotransposition between ORF1p and ORF2/3′ UTR (Fig. 5C, WT) (13). It is of interest that three CCHC motif mutants of ORF1p, H626P, H649A, and H672A, lost their binding activity to SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA (Fig. 6), indicating that the three CCHC motifs of ORF1 are essential for the packaging of their own mRNA into the SART1 complex. Unexpectedly, other ORF1p mutants in the first CCHC motif, C631H (CCHH), 623+A, and 623-AL (Fig. 2), packaged the ORF2/3′ UTR mRNA into the protein complex (Fig. 6, II) despite the loss of retrotransposition activity (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the three zinc fingers are involved in the packaging of SART1 RNA into the RNP complex and that H626P, H649A, and H672A mutations cause defects in RNA packaging. Since the C631H, 623+A, and 623-AL mutants can package SART1 mRNA but cannot retrotranspose, the zinc fingers may have other roles in retrotransposition, such as nucleic acid annealing shown in some retroviruses (35).

FIG. 6.

Detection of RNAs in the purified SART1 complex. Two AcNPV constructs, His-tagged SART1 ORF1 and HA-tagged SART1ORF2/3′ UTR, which produce the SART1 mRNA from nucleotides 880 to 3021 and 3018 to 6704, were coinfected into Sf9 cells. RNAs isolated from the SART1 complex were purified by Ni-NTA agarose (elution fraction). The Sf9 rPL3 gene was tested as a cellular control. The region of residues 1785 to 2585 (I) was amplified by RT-PCR for detection of RNA derived from SART1 ORF1, and the region of residues 6131 to 6702 (II) was used for detection of RNA derived from SART1 ORF2/3′ UTR.

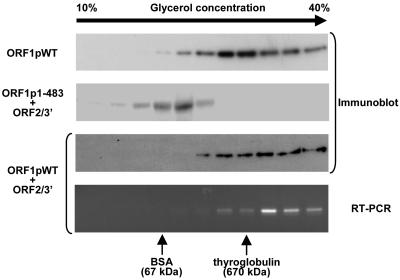

Large protein complex of SART1 detected by density gradient sedimentation.

Because the retrotransposable machinery of SART1 constitutes the RNP complex, as described above, we next tried to characterize the protein complex substance by density gradient sedimentation (Fig. 7). We expressed SART1 His-tagged ORF1p in Sf9 cells and fractionated the cell extracts by 10% to 40% glycerol gradient sedimentation. ORF1p in each fraction was detected by immunoblotting using an anti-His tag antibody. The distribution of the ORF1p fraction (80-kDa His-tagged ORF1p monomer) represents a similar or larger molecular mass than the standard marker thyroglobulin (670 kDa), indicating that the SART1 ORF1p forms a multimer with itself (Fig. 7, ORF1pWT). Coexpression of His-tagged SART1 ORF1p and ORF2p/3′ UTR (123-kDa monomer) caused the ORF1p to be detected mainly in fractions over 670 kDa, indicating that the ORF1p-ORF2p complex is presumably formed (Fig. 7, ORF1pWT+ORF2/3′). In addition, RNAs of SART1 ORF2/3′ colocalized with ORF1p (Fig. 7, RT-PCR). The broad distribution patterns of fractions including ORF proteins imply that there are various forms of SART1 protein complexes, at least under the conditions used in this study. Importantly, when the C-terminal His-tagged ORF1p mutant with a deletion of residues 484 to 712, a construct which lacks the capacity for ORF1p-ORF1p, ORF1p-ORF2p, and ORF protein-RNA interactions, was coexpressed with ORF2p/3′ UTR and fractionated, ORF1p distribution was found only around the 67 kDa (BSA) fraction (ORF1p1-483+ORF2/3′), indicating RNP formation deficiency. These results strongly suggest that the RNP complex of SART1 is formed stably through the ORF1p function.

FIG. 7.

Glycerol gradient sedimentation of purified SART1 complex. The eluate fraction including the SART1 complex was centrifuged through 10 to 40% glycerol gradients. Distributions of thyroglobulin (molecular size, 670 kDa) and BSA (molecular size, 67 kDa) are shown as standard markers. The ORF1 and ORF2/3′ construct were expressed with His and HA tag, respectively (Fig. 6). After the SART1 RNP complex was purified by Ni-NTA agarose, it was centrifuged and fractionated. The ORF1p for each fraction was detected by anti-His antibody. The bottom panel represents RT-PCR of RNAs from the region of residues 6131 to 6702 from each fraction of ORF1pWT+ORF2/3′ (Fig. 6). ORF1pWT, the AcNPV construct including only ORF1 of SART1; ORF1p1-483, the AcNPV construct including only residues 1 to 483 of ORF1, in which the CCHC motifs and ORF protein interaction region are deleted; ORF2/3′, the AcNPV construct including ORF2 and the 3′ UTR of SART1; ORF1p1-483+ORF2/3′, coexpression of ORF1p1-483 and ORF2/3′; ORF1pWT+ORF2/3′, coexpression of ORF1pWT and ORF2/3′.

DISCUSSION

Using the reconstitution system together with the retrotransposition assays, we have clarified that the ORF1 protein has specific domains required for RNP formation of SART1. Figure 8A summarizes the results of our mutation studies (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) and the functional domains identified within ORF1p (Fig. 8B). Our previous study showed that the N-terminal region of ORF1p encodes novel nuclear import signals and that the central region encodes putative telomere targeting signals (20). Here, we found three new functional roles of the C-terminal regions of SART1 ORF1p that are essential for the SART1 retrotransposition (Fig. 8B). Three CCHC motifs in the C terminus are involved mainly in packaging SART1 RNA into the SART1 RNP. Amino acid residues 555 to 567 control the ORF1p-ORF1p interaction, and the same segment (residues 555 to 567) together with the residues 285 to 554 is involved in the ORF1p-ORF2p interaction. Our data are the first direct evidence that the ORF1p in non-LTR retrotransposons plays important roles at each steps of the RNP formation in the non-LTR retrotransposable unit.

In vivo reconstitution of the functional SART1 RNP complex.

We succeeded in purifying functional SART1 RNP by coexpressing ORF1 and ORF2/3′ UTR in Sf9 cells using the baculovirus system, which expresses these products effectively. The SART1 RNP purified by this system retains the TPRT activity (Fig. 3). These novel reconstitution and retrotransposition assays using the baculovirus expression system will lead to better understanding of RNP formation in non-LTR elements.

The results shown in Fig. 4 and 5 clearly demonstrate that ORF1p and ORF2p of SART1 can be reconstituted when two differently tagged constructs are expressed in the same Sf9 cells. However, when the two constructs were expressed and purified separately in the Sf9 cells and the products were mixed in vitro, we could not detect the ORF1p-ORF1p or the ORF1p-ORF2p interactions (data not shown). In addition, three CCHC motif mutants were rescued in vivo by coexpression of WT ORF1p (Fig. 2B), but the purified ORF1p could not rescue the CCHC motif mutants in vitro (Fig. 3C). Because purified H626P, H649A, and H672A complexes lack template RNAs (Fig. 6), it is not strange that they do not have TPRT activity even when the purified WT ORF1p is added (Fig. 3C). However, the purified C631H, 623+A, and 623-AL mutants, which retain the SART1 RNAs (Fig. 6), lacked the TPRT activity even when WT ORF1p was added (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that some host factors in the insect cells may be involved in the SART1 complex reconstitution. Luschnig et al. reported that when Ty1, a yeast LTR-retrotransposon was expressed in Escherichia coli, the VLP was not identical to that constituted in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, supporting the notion mentioned above (18). Cellular chaperone activities or immediate reconstitution after de novo translation in the Sf9 cells may be necessary for formation of the functional SART1 RNP. A full understanding of the involvement between non-LTR retrotransposons and host factors in RNP formation awaits future studies using cell-free biosynthesis and other experiments.

The domains involved in the protein interaction in SART1 and other retroelements.

The amino acid residues 555 to 567 of ORF1p are essential for both the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions (Fig. 4 and 5) and for retrotransposition in vivo (Fig. 5C and 8A). In retroviruses, Gag proteins have a highly conserved stretch of 20 amino acids, termed the major homology region (MHR) (7), which is also observed in the yeast LTR retrotransposon, Ty3 (23). Several mutation studies have shown that MHR plays an important role in the Gag protein interaction, assembly, and maturation steps (3, 29). Recently, Rashkova et al. reported that non-LTR retrotransposons of Drosophila, HeT-A and TART, also have the MHR-like domain just before the CCHC motifs in ORF1, and colocalization analysis has shown that it is important for the ORF1p-ORF1p interactions (25). In contrast, even though we searched the whole ORF1 region, we did not find MHR-conserved amino acids in SART1. We found no sequence similarity between the protein-binding regions of SART1 ORF1 (the region of residues 555 to 567 and its surrounding area) and MHR, although their locations just before the CCHC motifs are analogous (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). In addition, computer simulation (http://www.cbrc.jp/papia-cgi/ssp_menuJ.pl) suggests that this SART1 protein-binding region includes two helices (residues 542 to 558 and 565 to 573) (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). The crystal structure of HIV-1 shows that two helices typically found in the MHR of nucleocapsid protein are critical for protein binding (7). These observations imply that, although the protein-binding domain in SART1 ORF1p has a different primary structure from MHR, it functions in a similar way to retrovirus MHR.

It is interesting that CCHC-motif mutants of SART1 did not affect the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions (Fig. 4, 5, and 8A). In retroviruses, the CCHC motifs in Gag protein are thought to contribute the interactions between the Gag protein monomers (33). The histochemical studies indicated that HeT-A Gag protein lacking CCHC motifs could not interact with proteins (25). In contrast, ORF1p of human L1, which has no CCHC motif, multimerizes to form protein complexes (15). These data suggest that not all retroelements use CCHC motifs to multimerize and also that some non-LTR elements such as SART1 and L1 can form the protein complex without the help of CCHC motifs, unlike retroviruses.

Do CCHC motifs of SART1 ORF1 work at various steps of the life cycle?

We found that three CCHC mutants in which the third H was replaced lost both the ability to package RNA into RNP and the retrotransposition activity (Fig. 8A, H626P, H649A, and H672A). Based on the structural features, we speculate that these mutants lack the ability to coordinate Zn2+ appropriately. Interestingly, a CCCC mutant at motif 1 (Fig. 8A, H626C) can bind RNA and retrotranspose normally, but a CCHH mutant at motif 1 (Fig. 8A, C631H), which retains an RNA-packaging ability, lacks the retrotransposition ability. In Mo-MuLV, CCCC and CCHH mutants retaining the ability to coordinate Zn2+ can package their genomic RNA normally but are replication defective (11), which seems to parallel the RNA-binding abilities of SART1 CCCC and CCHH mutants. In HIV-1, which is more similar to SART1, the CCCC mutant packages viral RNA and retains a reduced level of infectivity, whereas the CCHH mutant packages 32% of RNA but is replication defective (10). We also found that changing the spacing of CCHC motif 1 retained the RNA-packaging ability but lost the retrotransposition activity (Fig. 8A, 623+A and 623-AL). By analogy to the retroviruses described above, mutations at CCHH, 623+A, or 623-AL of SART1 may affect some steps such as nucleic chaperone activity rather than RNA packaging activity. L1 ORF1 also has a region involved in both the RNP formation and downstream steps in the retrotransposition pathway (15). Therefore, retroelements including non-LTR retrotransposons have a domain that works in multiple steps in the life cycle to pack various functional domains in the limited space of the ORF.

RNA-binding specificity of retroelements.

As shown in Fig. 6, RNA packaging into the RNP complex requires three CCHC motifs of ORF1. We detected mRNA for the ORF2/3′ UTR portion only but not for ORF1 in the purified SART1 RNP. This suggests that the SART1 ORF protein specifically recognizes and interacts with mRNA of a portion of ORF2/3′ UTR through the function of the CCHC motifs of ORF1p.

When we expressed SART1 without the 3′ UTR and green fluorescent protein mRNA fused with the SART1 3′ UTR in Sf9 cells, the green fluorescent protein mRNA retrotransposed into telomeric repeats by trans complementation between SART1 ORF proteins and SART1 3′ UTR (24). Therefore, some unknown structure in SART1 ORF proteins should strictly recognize the 3′ UTR of SART1 mRNA. This implies that the CCHC motifs in ORF1p may recognize the 3′ UTR of SART mRNA, although we have no direct evidence at present. In contrast, several retroelements occasionally generate processed pseudogenes by reverse transcribing cellular mRNAs. For example, human L1 recognizes only the poly(A) tract at the 3′ end of its mRNA and possibly misidentifies cellular poly(A) mRNAs as a target. To repress this false recognition, which is harmful for the host, human L1 is thought to employ the cis preference rather than trans complementation (34). Some reports indicate that the L1 ORF1 protein binds non-sequence-specific RNAs in vitro (14) and that the Ty1 VLP contains other cellular RNAs as well as Ty1 RNA, which results in the pseudogene production (21). It is notable that L1 and Ty1 lack the CCHC motif in their ORF1p and Gag protein. Thus, the absence of the CCHC motif in these retroelements may lead to weak recognition of the template RNA.

We do not yet know which region of SART1 mRNA in ORF2 or the 3′ UTR is recognized by the CCHC motifs of SART1 ORF1. In addition, the detailed features of the ORF1p-ORF1p and ORF1p-ORF2p interactions are still obscure. Further biochemical and structural biological studies will help clarify the ORF1p-ORF1p, ORF1p-ORF2p, and ORF1p-mRNA interactions and the entire image of the RNP complex of SART1, which should lead to better understanding of the retrotransposition mechanism of non-LTR retrotransposons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and by a grant from the National Bio-Resource Project in Japan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg, J. M., and Y. Shi. 1996. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science 271:1081-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasco, M. A. 2005. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:611-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borsetti, A., A. Ohagen, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1998. The C-terminal half of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor is sufficient for efficient particle assembly. J. Virol. 72:9313-9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson, A., E. Hartswood, T. Paterson, and D. J. Finnegan. 1997. A LINE-like transposable element in Drosophila, the I factor, encodes a protein with properties similar to those of retroviral nucleocapsids. EMBO J. 16:4448-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Guzman, R. N., Z. R. Wu, C. C. Stalling, L. Pappalardo, P. N. Borer, and M. F. Summers. 1998. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 psi-RNA recognition element. Science 279:384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara, H., M. Osanai, T. Matsumoto, and K. K. Kojima. 2005. Telomere-specific non-LTR retrotransposons and telomere maintenance in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Chromosome Res. 13:455-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamble, T. R., S. Yoo, F. F. Vajdos, U. K. von Schwedler, D. K. Worthylake, H. Wang, J. P. McCutcheon, W. I. Sundquist, and C. P. Hill. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278:849-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert, N., S. Lutz-Prigge, and J. V. Moran. 2002. Genomic deletions created upon LINE-1 retrotransposition. Cell 110:315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodier, J. L., E. M. Ostertag, K. A. Engleka, M. C. Seleme, and H. H. Kazazian, Jr. 2004. A potential role for the nucleolus in L1 retrotransposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:1041-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorelick, R. J., T. D. Gagliardi, W. J. Bosche, T. A. Wiltrout, L. V. Coren, D. J. Chabot, J. D. Lifson, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 1999. Strict conservation of the retroviral nucleocapsid protein zinc finger is strongly influenced by its role in viral infection processes: characterization of HIV-1 particles containing mutant nucleocapsid zinc-coordinating sequences. Virology 256:92-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorelick, R. J., W. Fu, T. D. Gagliardi, W. J. Bosche, A. Rein, L. E. Henderson, and L. O. Arthur. 1999. Characterization of the block in replication of nucleocapsid protein zinc finger mutants from Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 73:8185-8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ijdo, J. W., R. A. Wells, A. Baldini, and S. T. Reeders. 1991. Improved telomere detection using a telomere repeat probe (TTAGGG)n generated by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima, K. K., T. Matsumoto, and H. Fujiwara. 2005. Eukaryotic translational coupling in UAAUG stop-start codons for the bicistronic RNA translation of the non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon SART1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:7675-7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolosha, V. O., and S. L. Martin. 2003. High-affinity, non-sequence-specific RNA binding by the open reading frame 1 (ORF1) protein from long interspersed nuclear element 1 (LINE-1). J. Biol. Chem. 278:8112-8117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulpa, D. A., and J. V. Moran. 2005. Ribonucleoprotein particle formation is necessary but not sufficient for LINE-1 retrotransposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:3237-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lander, E. S., L. M. Linton, B. Birren, C. Nusbaum, M. C. Zody, et al. 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409:860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luan, D. D., M. H. Korman, J. L. Jakubczak, and T. H. Eickbush. 1993. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell 72:595-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luschnig, C., M. Hess, O. Pusch, J. Brookman, and A. Bachmair. 1995. The gag homologue of retrotransposon Ty1 assembles into spherical particles in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 228:739-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik, H. S., W. D. Burke, and T. H. Eickbush. 1999. The age and evolution of non-LTR retrotransposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:793-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto, T., H. Takahashi, and H. Fujiwara. 2004. Targeted nuclear import of open reading frame 1 protein is required for in vivo retrotransposition of a telomere-specific non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon, SART1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:105-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell, P. H., C. Coombes, A. E. Kenny, J. F. Lawler, J. D. Boeke, and M. J. Curcio. 2004. Ty1 mobilizes subtelomeric Y′ elements in telomerase-negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae survivors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:9887-9898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okazaki, S., H. Ishikawa, and H. Fujiwara. 1995. Structural analysis of TRAS1, a novel family of telomeric repeat-associated retrotransposons in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4545-4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlinsky, K. J., J. Gu, M. Hoyt, S. Sandmeyer, and T. M. Menees. 1996. Mutations in the Ty3 major homology region affect multiple steps in Ty3 retrotransposition. J. Virol. 70:3440-3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osanai, M., H. Takahashi, K. K. Kojima, M. Hamada, and H. Fujiwara. 2004. Essential motifs in the 3′ untranslated region required for retrotransposition and the precise start of reverse transcription in non-long-terminal-repeat retrotransposon SART1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:7902-7913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rashkova, S., A. Athanasiadis, and M. L. Pardue. 2003. Intracellular targeting of Gag proteins of the Drosophila telomeric retrotransposons. J. Virol. 77:6376-6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth, J. F. 2000. The yeast Ty virus-like particles. Yeast 16:785-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki, T., and H. Fujiwara. 2000. Detection and distribution patterns of telomerase activity in insects. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3025-3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seleme Mdel, C., O. Disson, S. Robin, C. Brun, D. Teninges, and A. Bucheton. 2005. In vivo RNA localization of I factor, a non-LTR retrotransposon, requires a cis-acting signal in ORF2 and ORF1 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:776-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasakumar, N., M. L. Hammarskjold, and D. Rekosh. 1995. Characterization of deletion mutations in the capsid region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that affect particle formation and Gag-Pol precursor incorporation. J. Virol. 69:6106-6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi, H., S. Okazaki, and H. Fujiwara. 1997. A new family of site-specific retrotransposons, SART1, is inserted into telomeric repeats of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1578-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi, H., and H. Fujiwara. 1999. Transcription analysis of the telomeric repeat-specific retrotransposons TRAS1 and SART1 of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:2015-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi, H., and H. Fujiwara. 2002. Transplantation of target site specificity by swapping the endonuclease domains of two LINEs. EMBO J. 21:408-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanchou, V., D. Decimo, C. Pechoux, D. Lener, V. Rogemond, L. Berthoux, M. Ottmann, and J. L. Darlix. 1998. Role of the N-terminal zinc finger of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in virus structure and replication. J. Virol. 72:4442-4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei, W., N. Gilbert, S. L. Ooi, J. F. Lawler, E. M. Ostertag, H. H. Kazazian, J. D. Boeke, and J. V. Moran. 2001. Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1429-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams, M. C., R. J. Gorelick, and K. Musier-Forsyth. 2002. Specific zinc-finger architecture required for HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein's nucleic acid chaperone function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8614-8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia, Q., Z. Zhou, C. Lu, D. Cheng, F. Dai, et al. 2004. A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 306:1937-1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.