Abstract

Starch in synchronously grown Guillardia theta cells accumulates throughout the light phase, followed by a linear degradation during the night. In contrast to the case for other unicellular algae such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, no starch turnover occurred in this organism under continuous light. The gene encoding granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS1), the enzyme responsible for amylose synthesis, displays a diurnal expression cycle. The pattern consisted of a maximal transcript abundance around the middle of the light phase and a very low level during the night. This diurnal regulation of GBSS1 transcript abundance was demonstrated to be independent of the circadian clock but tightly light regulated. A similar yet opposite type of regulation pattern was found for two α-amylase isoforms and for one of the two plastidic triose phosphate transporter genes investigated. In these cases, however, the transcript abundance peaked in the night phase. The second plastidic triose phosphate transporter gene had the GBSS1 mRNA abundance pattern. Quantification of the GBSS1 activity revealed that not only gene expression but also total enzyme activity exhibited a maximum in the middle of the light phase. To gain a first insight into the transport processes involved in starch biosynthesis in cryptophytes, we demonstrated the presence of both plastidic triose phosphate transporter and plastidic ATP/ADP transporter activities in proteoliposomes harboring either total membranes or plastid envelope membranes from G. theta. These molecular and biochemical data are discussed with respect to the environmental conditions experienced by G. theta and with respect to the unique subcellular location of starch in cryptophytes.

One of the most fascinating and important biological processes on Earth is the light-driven fixation of carbon dioxide called photosynthesis. Apart from cyanobacteria, photosynthesis is performed by red algae (Rhodophyta), green plants (Viridaeplanta), and blue-green Glaucophyta, and all of these groups arose by a single ancient symbiosis (primary endosymbiosis) between a protozoan host and a cyanobacterium. During this process the cyanobacterium converted into a primary chloroplast surrounded by an envelope consisting of an inner membrane and an outer membrane (1).

Interestingly, many eukaryotic algae acquired photosynthesis through a process called “secondary endosymbiosis,” which gave rise to even more complex chimeric eukaryotes (chlorarachneans and chromalveolates). The nonphotosynthetic host obtained its plastid by engulfing a phototrophic eukaryote with a primary chloroplast. There is ample evidence that all chromalveolates comprising Cryptophyta, Chromobiota, and Alveolata evolved by an engulfment of a red alga by a bikont eukaryotic cell (28). Necessarily, this merger of two eukaryotic cells was accompanied by a substantial genetic rearrangement and modification of the cellular structure (20), such as the gain of secondary plastids with four bounding membranes (2). The two innermost membranes are derived from the plastid envelope of the red algal symbiont, the second outermost membrane encloses the former cytosol of the symbiont (periplastid compartment), and in chromobiotes and cryptomonads the outer membrane is connected with the endoplasmic reticulum of the host cell (34).

Photosynthetic fixation of carbon dioxide leads to the generation of storage products such as soluble sugars (e.g., sucrose) or insoluble starch. While sucrose acts as a major transport form of carbohydrates, chloroplastidic starch functions as temporary storage for carbon and energy required during the night phases (38). In higher plants and green algae, the plastidic (stromal) localized starch biosynthesis starts with the provision of ADP-glucose, which serves as a carbon donor for elongation of an existing starch core (15, 33, 37). This elongation is mediated by two isoforms of starch synthases, a soluble starch synthase and a granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) (27).

However, the organization of starch metabolism in the red lineage of algae is totally different from that in the green lineage of photoautotrophs. For example, red algae store starch outside the plastid in the cytosol (23), and the starch synthases accept UDP-glucose as a substrate (3, 21, 37).

Remarkably, although algae harboring complex plastids contribute significantly to annual CO2 fixation on Earth (29), our knowledge about starch synthesis in these species is much less than that about starch synthesis in higher plants. In recent years Guillardia theta has been developed as a model cryptomonad, because the genome of the vestigial nucleus (nucleomorph), residing in the periplastid compartment, has been sequenced (5) and isolated plastids are able to import preproteins exhibiting cryptomonad-specific import/target signatures (35). Moreover, G. theta is also interesting since starch resides neither in the stroma (as in green lineages of photoautotrophs) nor in the cytoplasm (as in red algae) but in the periplastid compartment (9). This subcellular location of starch concurs with the unique bipartite structure of the GBSS1 transit sequence identified by us (10).

In this study we were interested in revealing mechanisms causing changes of starch levels in Guillardia theta during consecutive day/night cycles. Therefore, we focused on the regulation of genes involved in starch turnover, and we wanted to elucidate the nature of carrier proteins involved in photosynthate export and energy provision in complex plastids. The regulatory processes and their implications for starch levels in G. theta are discussed in comparison to regulation of starch synthesis in green algae and higher plants and with respect to the environmental conditions experienced by free-living G. theta cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Guillardia theta.

A culture of Guillardia theta, strain CCMP 327 (Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton), was maintained and grown in h/2 marine medium (11) (lacking silica) under alternating light/dark conditions (12 h light/12 h dark). For studies concerning enzyme activity, starch quantification, Northern blot analysis, membrane preparations, and plastid isolation, synchronized cultures were grown for a minimum of 2 days in 1,000-ml aerated glass tubes under the light regimen stated above.

Cultures were inoculated at the early log phase and sampled after 2 to 3 days. For analysis of diurnal starch turnover and regulation of transcription, actively growing cells were sampled every 2 to 3 hours and fresh medium was added immediately to compensate medium volume reduction and to obtain a constant cell density. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (2,000 × g, 10 min).

Isolation of plastids and preparation of total membranes.

Actively growing synchronized cells were harvested at the middle of the light phase, and plastids were purified by density gradient centrifugation (35). The purity and integrity of the plastid fraction were proven microscopically, by latency analysis of stromally located NADP-GAPDH (intactness of >90%), and by quantification of the mitochondrial marker enzyme fumarase and the peroxisomal marker catalase (22). According to this analysis, mitochondrial contamination was less than 2% (standard error [SE], ±2%; n = 4) and peroxisomal contamination was 4.3% (SE, ±3%; n = 4). For preparation of total membranes, crude extracts of disrupted algae were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min to remove starch and cell debris. Afterwards, membranes in the supernatant were sedimented by centrifugation at 100,000 × g.

Reconstitution of transport proteins either from total membranes or from isolated plastids in proteoliposomes and transport experiments.

Proteoliposomes containing total membrane proteins or proteins from the two innermost plastid membranes were prepared as described previously (17). Liposomes were prepared from soybean phosphatidylcholine (100 mg/ml) by sonication in 100 mM Tricine-NaOH (pH 7.5) and 30 mM K-gluconate, with or without 10 mM counterexchange substrate for preloading. Total membrane proteins as well as proteins from purified plastids were solubilized by adding 0.01% (vol/vol) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside. Fifty micrograms of the corresponding protein preparation was incorporated into 500 μl of liposomes by a freeze-thaw step. After thawing, proteoliposomes were sonicated for 20 s and external counterexchange substrate was removed using NAP-5 gel filtration columns (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden) as described previously (17).

Transport of [32P]phosphate or [32P]ATP into proteoliposomes was measured as described previously (17). Incubation was initiated by adding 100 μl proteoliposomes to 100 μl transport medium containing the indicated concentrations of labeled substrates. Uptake was conducted at 30°C and terminated by use of anion-exchange columns (Dowex 1x8, 200 to 400 mesh; Sigma Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany) (17). To suppress the activity of contaminating mitochondrial ADP/ATP carriers, nucleotide transport experiments were carried out in the presence of 20 μM bongkrekic acid, which is known to be a highly specific and efficient inhibitor of mitochondrial and hydrogenosomal ADP/ATP carrier proteins but not of plastidic (NTT-type) ATP/ADP transporters (19, 30).

Starch quantification.

Cell sediments were resuspended in 1 ml extraction buffer medium consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. Preparation of starch was conducted as previously described (4a). Quantification of total polysaccharide was performed using the starch assay kit from Boehringer-Roche (Mannheim, Germany).

Measurements of GBSS1 activity.

GBSS1 from 400 ml of actively growing cell culture was extracted, and activity was measured as described previously (21). For this, harvested Guillardia theta cells were ground in liquid nitrogen and resuspended (corresponding to 100 μg protein) in buffer medium (0.1 M Bicine-KOH [pH 8.0], 0.5 M Na-citrate, 2 mM UDP-[U-14C]glucose [NEN, Bad Homburg, Germany], and 15 mg/ml glycogen). Incorporation of labeled glucose into starch was performed at 30°C for 15 min. Nonincorporated radioactivity was removed by use of anion-exchange columns. The flowthrough was collected, and radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting.

cDNA preparation and cloning of partial and full-length sequences.

Total RNA was isolated from Guillardia theta cells by use of the RNeasy plant minikit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Poly(A+) mRNA was subsequently isolated by use of the Oligotex kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and converted to cDNA by reverse transcription using SuperscriptII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA isolation and reverse transcription were performed according to the supplier's instructions. DNA manipulations were performed as described previously (26). The partial cDNA clones corresponding to two putative amylases (Amy1 and Amy2), the partial clones corresponding to two putative triose phosphate/phosphate antiporters (TPT1 and TPT2), and the full-length cDNA clone of the GBSS1 gene were amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Specific primers were designed according to sequence information from the Guillardia theta expressed sequence tag (EST) project (Uwe Maier, Marburg, Germany) as follows: Amy1 sense, 5′-GGTCAAGGCACAACATGAAGTACGCCTTGG-3′; Amy1 antisense, 5′-CGATCAACTTTCAGCCTAGTGTACGCTAAG-3′; Amy2 sense, 5′-GAAGAGTGGTACTTTATTTCCGAAGGAAACAGC-3′; Amy2 antisense, 5′-GGAAGAGAGTTGGAGGGATCCGTTTTCACG-3′; TPT1 sense, 5′-AAGCCGTCGGAGTCCAACATGAAGGCCCTCC-3′; TPT1 antisense, 5′-TGCACGAGCGAGTACACGAGAACTCCCCCC-3′; TPT2 sense, 5′-TAATGGCGAACACAACGAAGCTCGTGCTGC-3′; TPT2 antisense, 5′-GCATGCAGCAGCACCGTCAGCCAAGCGTGG-3′; GBSS1 sense, 5′-GTTGGACGTCAAAAGAAGGCTTCCAAGGGC-3′; and GBSS1 antisense, 5′-TCATTACAACAACATCACAGATTCACATGC-3′. The resulting amplification products were gel purified by use of the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Macherey & Nagel, Düren, Germany) and inserted into the vector pBSK (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). The newly constructed plasmids were transformed and maintained in Escherichia coli XL1Blue (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). Plasmid purification was conducted by use of the QIAprep spin miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and identities of the cloned genes were verified by restriction analysis with specific restriction endonucleases according to manufacturer's recommendations (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and sequencing (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany).

Extraction of total RNA and RNA gel blot hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from the sediment of 400 ml of frozen (with liquid nitrogen) harvested algae by using the Purescript extraction kit (Gentra Systems, North Minneapolis, MN). RNA gel blot hybridization analysis was carried out using standard methods (26) and visualized using a phosphorimager (Packard, Frankfurt, Germany).

RESULTS

Mechanisms controlling diurnal turnover of starch.

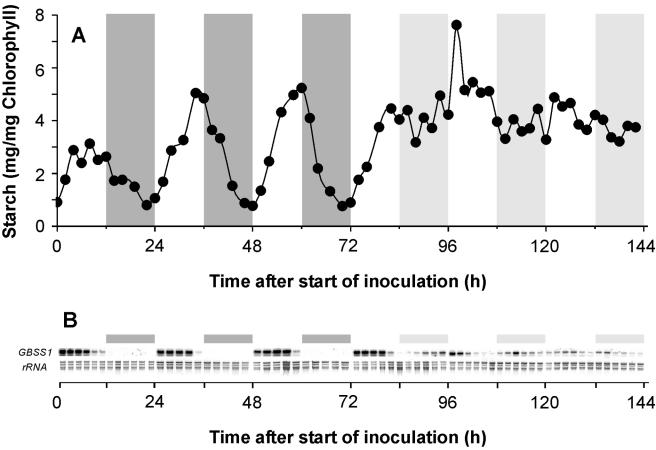

Within three consecutive day/night cycles, starch accumulates in the light phases and declines in the corresponding night phases (Fig. 1A). The maximal starch level in the first light phase after inoculation of the Guillardia theta culture was only 60% of the value present in the consecutive light phases (phases two and three) (Fig. 1A). Taking light phases two (24 to 36 h) and three (48 to 60 h) after the start of inoculation as representative, we observed a net rate of starch synthesis of 4.13 mg/mg chlorophyll/12 h (Fig. 1A). This value corresponds to a carbon flux equivalent to 1.91 μmol C6/mg chlorophyll/h.

FIG. 1.

Diurnal starch turnover and accumulation of GBSS1 mRNA. Precultures of G. theta were synchronized for 14 days under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. To start the experiment, cells were inoculated in the early log phase and were kept under the previously applied light/dark cycles for 3 days, before cultivation for 3 days under continuous light. Dark gray bars indicate the corresponding night phases, and white areas indicate the corresponding day phases. The light gray boxes represent the time spans of previous dark phases under conditions of permanent light. At days 1, 5, and 6 cells were harvested every second hour. At days 2, 3, and 4 cells were harvested at 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 a.m. and p.m. (A) Diurnal starch turnover. (B) Northern blot analysis of GBSS1 mRNA accumulation under changing light conditions during 6 days. Starch levels are the means from three independent replicates. SEs of mean values were less than 9%, with the exception of the mean starch level measured 98 h after start of the inoculation, which exhibited an SE of 32%. Total RNA (10 μg) was extracted from 400 ml of algae harvested at the indicated time points. Ethidium bromide staining of rRNA represents loading controls. The Northern blot analysis represents a typical expression pattern as observed in three independent biological replicates.

To investigate the putative persistence of the starch turnover in continuous light, we also monitored the levels of this polysaccharide over 72 h of constant illumination (Fig. 1A). During continuous light phase which followed the three consecutive day/night cycles, no starch breakdown in Guillardia occurred. This observation is a first indication that the diurnal starch accumulation in Guillardia is governed by light and not by the circadian clock.

Diurnal regulation of genes and enzymes involved in starch turnover.

To get a better understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms governing starch turnover in Guillardia theta, we monitored the patterns of expression of genes involved in starch metabolism. GBSS1 mRNA accumulated rapidly to a high level at 1 hour after start of the light phase (Fig. 1B). This level of GBSS1 mRNA stayed constant for about 6 hours within the light phase and declined towards the end of the photosynthetic period (Fig. 1B). At the end of the light phase (the last 4 hours), the level of GBSS1 mRNA was already very low, and it remained close to the detection limit in the dark phase (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, these substantial diurnal changes of GBSS1 mRNA levels disappeared within the first 36 h of permanent illumination (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, GBSS1 mRNA levels remained constantly low (Fig. 1B).

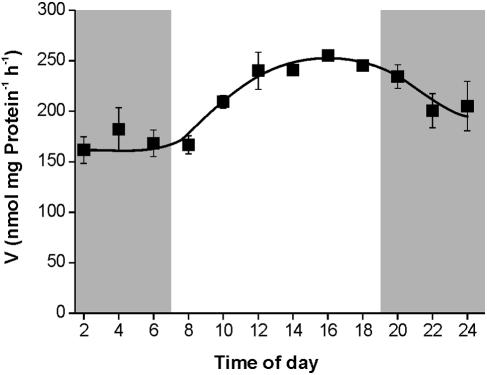

As shown above, the level of G. theta GBSS1 mRNA displayed large variations within a single light/dark cycle (Fig. 1B). As starch synthesis seems to be strictly coregulated (Fig. 1A), it was interesting to analyze whether GBSS1 activity levels correlated to GBSS1 mRNA. GBSS1 activity during the night phase remained constant at about 175 nmol/mg protein/h (Fig. 2). However, upon onset of light, this activity increased by about 43% to a maximum of 250 nmol/mg protein/h within the first 8 hours of light and stayed nearly constant at that level until the end of the light phase. After the onset of darkness, GBSS1 activity declined to about 200 nmol/mg protein/h at 12 p.m. (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Diurnal alteration of GBSS1 activity. Cells were synchronized for 3 days as described in the text. Cell sediments (each point corresponds to 400 ml of culture) were ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted with about 3 volumes of extraction medium. GBSS1 activity was estimated as incorporation of radiolabel deriving from UDP-[U-14C]glucose into glycogen. As controls, incorporation was performed either on ice or with heat-denatured sample (15 min, 95°C). Data represent the means from three independent experiments. Standard errors are given. Dark gray bars indicate the dark phases; the white area indicates the light phase.

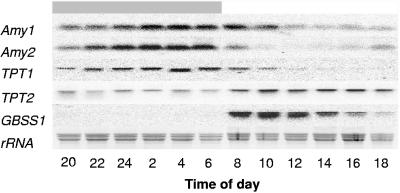

Two partial mRNA sequences coding for the starch-degrading enzymes α-amylase 1 (Amy1) and α-amylase 2 (Amy2) were discovered in the data from the ongoing Guillardia EST project. Interestingly, both mRNA species accumulated similarly after the onset of darkness and reached a maximal level at 7 hours past the end of the light phase (Fig. 3). After the start of illumination, Amy1 and Amy2 mRNAs declined rapidly, and they remained at a constant low level throughout the entire light phase (Fig. 3). The mRNAs of both amylase genes show an expression pattern opposite to that for the GBSS1 mRNA (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Diurnal expression analysis of mRNA accumulation for several genes involved in starch turnover. Diurnal mRNA changes in amylase 1 (Amy1), amylase 2 (Amy2), triose phosphate/phosphate translocator 1 and 2 (TPT1 and TPT2), and GBSS1 were monitored. Alterations of transcripts were detected by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA (10 μg) was extracted from a 400-ml algal culture synchronized for 2 days under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points, and total RNA was separated by electrophoresis before transfer onto a nylon membrane. Blots were hybridized with Amy1-, Amy2-, TPT1-, TPT2-, and GBSS1-specific probes. Ethidium bromide staining of total RNA reveals equal loading. The dark gray bar indicates the corresponding dark phase, and the white bar indicates the light phase. The Northern blot analysis represents a typical expression pattern as observed in three independent biological replicates.

Within the data from the ongoing EST project we also discovered two mRNAs coding for proteins annotated as a putative plastidic triose phosphate/phosphate transporters (TPT1 and TPT2). Since this carrier activity is crucially involved in carbohydrate transport across the envelopes of plastids from higher plants (7), it was interesting to analyze the expression patterns of the corresponding genes in G. theta.

The level of TPT1 mRNA followed the Amy1 and Amy2 mRNA oscillation pattern (Fig. 3). TPT1 mRNA accumulated within the first 5 hours of the night phase and remained at a high level until the end of the night (Fig. 3). Immediately after the onset of illumination, the TPT1 mRNA level dropped, and it reached the lower detection limit after about 5 hours (Fig. 3). During the complete night phase, TPT2 mRNA remained at a low level, and then it accumulated substantially between 6 and 8 a.m. (Fig. 3). The TPT2 mRNA level further increased until 10 a.m., remained high until 4 p.m., and slightly declined thereafter towards the end of the light phase (Fig. 3). This slight decrease towards the end of the light phase resembles the expression pattern of GBSS1 (Fig. 1B), and both examples indicate that gene expression in G. theta is not triggered exclusively by the light stimulus.

Effect of a sudden light/dark switch on the expression of genes involved in starch biosynthesis.

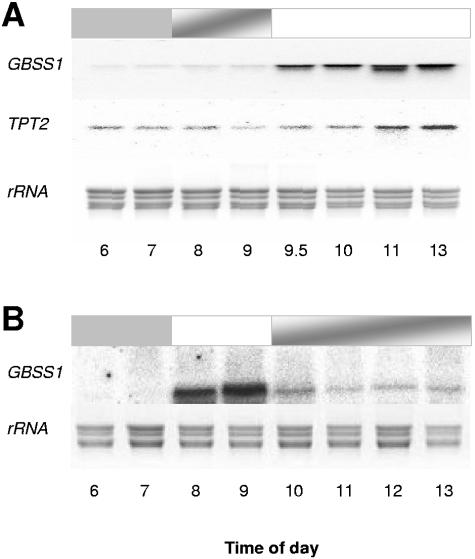

Constant illumination of Guillardia theta following alternating light/dark phases yielded a stable high expression level of GBSS1 mRNA (Fig. 1B). Data from the experiment presented in Fig. 3 argue for the presence of light-controlled up-regulation of GBSS1 and TPT2. To analyze the effect of illumination in more detail, we first grew G. theta for 2 days in the standard light/dark cycle and then delayed the start of the third light phase for 2 hours (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Changes in GBSS1 and TPT2 transcript accumulation under sudden light/dark changes. Alterations of GBSS1 and TPT2 gene expression under sudden light/dark changes were detected by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA was extracted from 400 ml of synchronized algae harvested at the indicated time points. Blots were hybridized with a TPT2- or GBSS1-specific probe. Ethidium bromide staining reveals equal RNA loading. Dark gray bars indicate the dark phase, and white bars indicate the corresponding light phase. The gray shaded boxes represent phases of unexpected darkening. The Northern blot analysis represent a typical expression pattern as observed in three independent biological replicates.

As displayed in Fig. 4A, GBSS1 and TPT2 mRNAs were either absent or at low levels, respectively, without the light signal occurring normally at 7 a.m. However, after onset of the delayed illumination, both mRNA species accumulated in Guillardia (Fig. 4A). As demonstrated above, GBSS1 mRNA declined towards the end of the light phase in standard light/dark cycles (Fig. 1B). Therefore, it was interesting to analyze how sudden darkness might also affect the accumulation of GBSS1 mRNA. For this experiment we first grew G. theta for 2 days in standard light/dark conditions. In the third cycle we turned the lights on for only 2 hours and then switched them off (Fig. 4B). As displayed in Fig. 4B, the level of GBSS1 mRNA declined rapidly after onset of darkness and remained at a constant low level.

Activity of transport proteins involved in starch metabolism in Guillardia theta.

In Guillardia theta starch resides outside the stroma in the periplastid compartment. This spatial separation predicts comparable large metabolic fluxes between the plastid and the surrounding periplastid compartment. In higher plants the chloroplastic triose phosphate/phosphate antiporter is the major carrier protein catalyzing the efflux of photosynthate into the cytosol (7). In addition both heterotrophic plastids and certain types of chloroplasts have been found to contain hexose phosphate/phosphate transporters mediating transmembrane movement of either glucose 6-phosphate (Glc6P) or, possibly, glucose 1-phosphate (Glc1P) (7, 18). However, up to now the plastidic phosphate transporter complement of cryptophytes has never been analyzed. Therefore, we conducted uptake experiments with reconstituted total membranes either from whole G. theta cells or from purified intact plastids harboring the two innermost membranes (35).

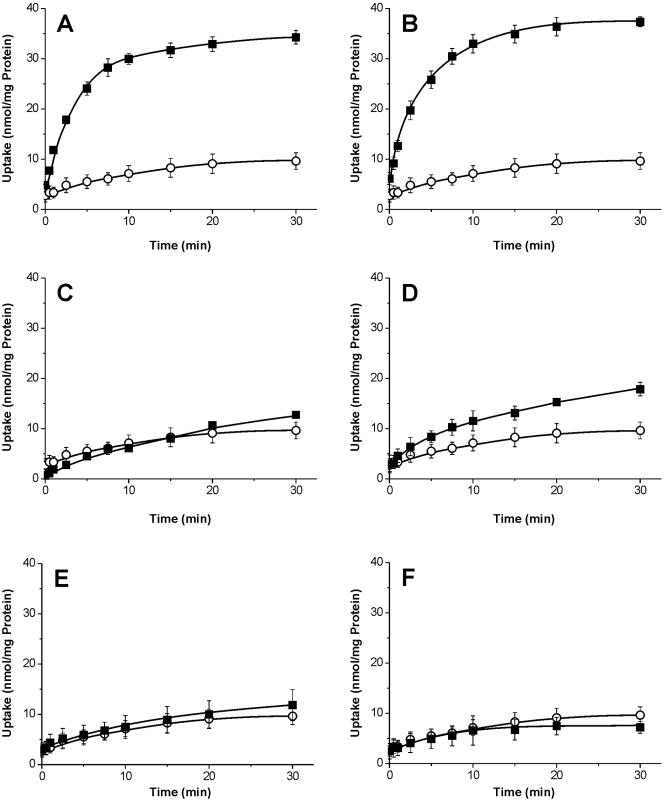

As shown in Fig. 5A, total G. theta membranes contain a phosphate/phosphate (Pi/Pi) antiport activity as is present in plastids from higher plants. In addition to Pi/Pi exchange, the corresponding carrier is also able to catalyze a dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP)- or phosphoenolpyruvate-driven counterexchange of Pi (Fig. 5B and D), whereas glycerate 3-phosphate, Glc6P, or Glc1P does not stimulate uptake of 32Pi into proteoliposomes (Fig. 5C, E, and F).

FIG. 5.

Time dependency of 32Pi uptake into proteoliposomes. Proteoliposomes harboring 50 μg of total membrane proteins from G. theta were incubated in uptake medium containing 0.1 mM α-32Pi for the indicated time periods. Proteoliposomes were preloaded with 10 mM of various putative counterexchange substrates (▪) or did not contain the putative counterexchange substrate (unloaded controls, ○). (A) Pi-stimulated uptake; (B) DHAP-stimulated uptake; (C) glycerate 3-phosphate-stimulated uptake; (D) phosphoenolpyruvate-stimulated uptake; (E) Glc6P-stimulated uptake; (F) Glc1P-stimulated uptake. Data represent the means from three independent experiments (±SE).

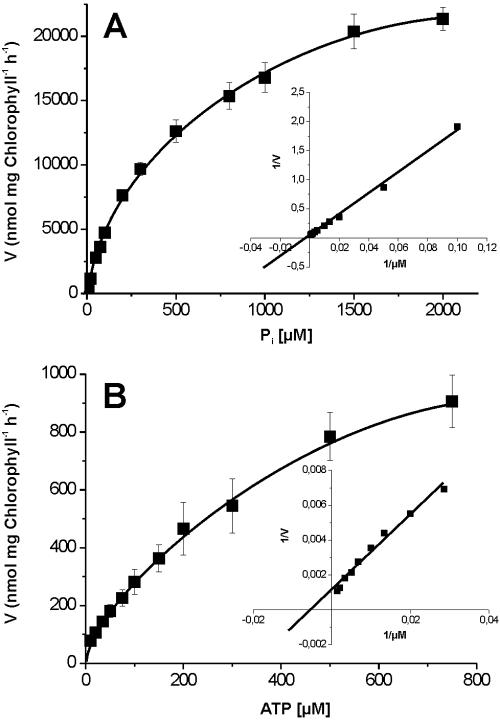

After reconstitution of membranes from enriched G. theta plastids, we were able to determine the apparent affinities (Km) and the Vmax of the plastidic phosphate transport system within a time-linear phase of 2 to 5 min. The plastidic phosphate transporter imports Pi (in counterexchange with DHAP) at a Vmax of 33 μmol/mg chlorophyll/h and exhibits an apparent Km of 0.62 mM (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Apparent Km and Vmax values of reconstituted plastidic triose phosphate/phosphate and plastidic ATP/ADP transport proteins. Phosphate uptake was performed for 3 min, and import of ATP was allowed for 6 min (linear phase of uptake). (A) Substrate saturation of [α-32P]phosphate uptake into proteoliposomes preloaded with 10 mM DHAP. (B) Substrate saturation of [α-32P]ATP import into proteoliposomes preloaded with ADP at a concentration of 10 mM. The insets represent double-reciprocal plots of phosphate or ATP uptake. ATP uptake was carried out in the presence of 20 μM bongkrekic acid to inhibit nucleotide transport catalyzed by contaminating mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier proteins. The data indicate an apparent Km of 623 μM and a Vmax of 33 μmol · mg chlorophyll−1 · h−1 for phosphate import and an apparent Km of 196 μM and a Vmax of 0.9 μmol · mg chlorophyll−1 · h−1 for ATP import. Data are the means and SEs from four independent experiments.

In addition to the transport of phosphorylated sugars, we also monitored the transport of nucleotides via the plastidic nucleotide transporter NTT. Proteoliposomes containing proteins from enriched G. theta plastid membranes exhibited a time-linear uptake of ATP (data not shown). Analysis of the concentration dependency of ATP uptake into these proteoliposomes revealed an apparent Km of 0.19 mM and a Vmax of 0.9 μmol/mg chlorophyll/h (Fig. 6B). Proteoliposomes harboring total membranes exhibited a maximal bongkrekic acid-insensitive ATP uptake of 20 μmol/mg chlorophyll/h (SE, ±0.5 μmol/mg chlorophyll/h), indicating that most of the plastidic ATP/ADP transport activity resides in the two outermost and not in the two innermost membranes from G. theta plastids.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that starch levels in synchronized Guillardia theta cells increase throughout the light phase, reach a maximal level in the last part of the light period, and decrease within the subsequent night phase (Fig. 1A). This pattern of starch accumulation resembles diurnal changes of the starch levels in leaves from higher plants but not those found in other unicellular algae such as, e.g., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Higher plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana accumulate transitory starch throughout the entire light phase and start degradation of this polysaccharide right after the onset of the dark phase (8). In contrast C. reinhardtii exhibits the lowest starch levels in the middle of the day, demonstrating rapid degradation of starch during the early phase of photosynthesis (32; S. Ball et al., unpublished data).

It appears remarkable that all genes tested that are involved either in starch turnover (GBSS1, α-Amy-1, and α-Amy-2) or in transport of photosynthetic intermediates (TPT1 and TPT2) exhibit a diurnal regulation of the expression level (Fig. 1A and 3). Moreover, we showed that changes of GBSS1 mRNA accumulation correlate to some extent with changes in the extractable enzyme activity (Fig. 1B and 2). However, we have to consider that altered GBSS1 activity (Fig. 2) might also be caused by a so-far-unknown type of posttranslational modification.

In general, circadian clock-controlled processes have to persist under constant conditions after a previous phase characterized by a diurnal pattern (16). In case of both diurnally changing starch levels and diurnally changing GBSS1 mRNA levels, we showed that constant illumination, after alternating light/dark cycles, yielded an uncontrolled stable behavior (Fig. 1A and B). This observation clearly reveals that light and not a circadian clock triggers the diurnal rhythm of both factors. In species such as C. reinhardtii or the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polyedra, the diurnal rhythms are governed by light-independent endogenous circadian clocks (25; Ball et al., unpublished data). As the diurnal rhythm of several genes in Guillardia is controlled by light (Fig. 3 and 4), we have to conclude that different unicellular algae exploit individual molecular mechanisms to control their diurnal rhythms.

So far it is unknown why G. theta, in contrast to other unicellular algae, exhibits a light-governed regulation of the diurnal rhythm. However, we might speculate that this is due to specific environmental conditions experienced by Guillardia. So far this species has been found in coastal regions of the United States (24) and in the Wadden Sea in Denmark (12). These zones are characterized by wind-driven upwelling (13, 24) and tide changes (29), which are known to provoke substantially changing light intensities. Therefore, the rapid light-controlled regulation of enzymes and processes ultimately connected to the presence of light is crucial. However, light-controlled diurnal rhythms might also turn out to be a general feature of cryptomonads.

We showed in our accompanying paper that isolated starch grains of G. theta typically exhibit a ball-shaped cavity (4a). Such cavities are also known to occur in starch grains extracted from other unicellular algae and are caused by the large pyrenoid (31). However, the cellular situation in G. theta is much more complex, since the pyrenoid remains in the stroma (4a) whereas starch resides outside in the periplastid compartment (9). In this context two questions arise. First, what kind of metabolites cross the two innermost envelope membranes separating the stroma from the periplastid compartment? Second, what is the putative energy source allowing starch biosynthesis in the periplastid compartment?

We demonstrated that plastids of G. theta possess a triose phosphate/phosphate transporter using mainly dihydroxyacetone phosphate as a counterexchange substrate against inorganic phosphate (Fig. 5). Interestingly, this carrier is not able to transport 3-phosphoglyceric acid (Fig. 5C), which is known to be a highly efficient substrate for the TPT from higher plants (6, 7). However, this feature of the G. theta TPT carrier resembles biochemical characteristics of the TPT from the red alga Galdieria sulfuraria (36). Considering that cryptomonads acquired photosynthesis through secondary endosymbiosis of a red alga (14), we have to assume that the biochemical properties of TPT have not been modified dramatically after entry of the symbiont into the host cell.

Remarkably, although G. theta is only a unicellular organism, this species contains at least two genes coding for plastidic phosphate transporters. We classified two of these genes as putative triose phosphate/phosphate transporters (TPT1 and TPT2) because proteoliposomes harboring total G. theta membranes import Pi in counterexchange with DHAP (Fig. 5A) but not in counterexchange with hexose phosphates such as Glc6P or Glc1P (Fig. 5E and F). Interestingly, the genes encoding TPT1 and TPT2 are regulated in opposite directions. TPT1 mRNA accumulates during the night phase, whereas TPT2 accumulates during the light phase (Fig. 3). Assuming that this expression pattern reflects the metabolic involvement of corresponding carrier proteins, we might assume that TPT2 resides in the innermost envelope membrane from G. theta plastids and catalyzes the export of triose phosphates generated during photosynthesis. In contrast, TPT1 might reside in the third and/or fourth membrane separating the periplastid space from the host cell cytoplasm. In the latter case, one function of TPT1 would be the export of starch degradation products during the night phase.

Assuming that the G. theta pyrenoid contains, similarly to green algae, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and other Calvin cycle enzymes (31) and assuming that the pyrenoid in G. theta is involved in starch biosynthesis, we have to predict that growth of the starch grain occurs on the inner surface of the ball-shaped cavity. For this process, not only triose phosphates have to enter the periplastid compartment but also energy in form of nucleotides. We cannot exclude the possibility that the highly specific ATP/ADP transporter of the NTT type located in the two innermost envelope membranes (Fig. 6B) might contribute to the nucleotide provision into the periplastid compartment. However, it seems more likely that most of the nucleotides required for starch biosynthesis in the periplastid compartment derive from the host cytosol. This assumption is in line with our finding that the two outermost membranes of Guillardia chloroplasts harbor more than 20-fold-higher NTT activity than the two innermost envelopes (Fig. 6B) (see Results).

As was reported for red algae (21, 36), starch synthases in G. theta depend upon the presence of UDP-glucose and not on ADP-glucose (4a). Therefore, the ball-shaped cavity must contain a nucleoside diphosphate kinase equilibrating the adenylate and the uridinylate pools. At least for higher plants, the presence of this enzyme in various cellular compartments (mitochondria, plastids, and the cytosol) has been documented (4), and we have verified that this enzyme is also highly active in G. theta (data not shown).

Our assumption that exported triose phosphates are converted within the periplastid compartment into UDP-glucose is supported by the fact that this compartment represents the cytosol of the formerly free-living red algae. Starch synthesis in red algae takes place in the cytosol (23) and requires the presence of all enzymes involved in this compartment. Moreover, although we have considerable experience in analyzing transport processes, we were unable to observe UDP-glucose transport activities on proteoliposomes harboring total G. theta membranes (data not shown). Of course, further work is required to analyze the subcellular distribution of critical enzymes required for starch biosynthesis in G. theta, and this work is in progress.

Acknowledgments

Work in the laboratory of Ekkehard Neuhaus has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Schwerpunkt: Intrazelluläre Lebensformen, SPP 1131), work in the laboratory of Uwe Maier has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Sonderforschungsbereich 593), and work in the laboratory of Steven Ball has been funded by the French Ministry of Education, the Centre de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cavalier-Smith, T. 1982. The origins of plastids. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 17:289-306. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalier-Smith, T. 2000. Membrane heredity and early chloroplast evolution. Trends Plant Sci. 5:174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppin, A., J. S. Varre, L. Lienard, D. Dauvillee, Y. Guerardel, M. O. Soyer-Gobillard, A. Buleon, S. Ball, and S. Tomavo. 2005. Evolution of plant-like crystalline storage polysaccharide in the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii argues for a red alga ancestry. J. Mol. Evol. 60:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dancer, J. E., H. E. Neuhaus, and M. Stitt. 1990. Subcellular compartmentation of uridine nucleotides and nucleoside-5′-diphosphate kinase in leaves. Plant Physiol. 92:637-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Deschamps, P., I. Haferkamp, D. Dauvillée, S. Haebel, M. Steup, A. Buléon, J.-L. Putaux, C. Colleoni, C. d'Hulst, C. Plancke, S. Gould, U. Maier, H. E. Neuhaus, and S. Ball. 2006. Nature of the periplastidial pathway of starch synthesis in the cryptophyte Guillardia theta. Eukaryot. Cell 5:954-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas, S., S. Zauner, M. Fraunholz, M. Beaton, S. Penny, et al. 2001. The highly reduced genome of an enslaved algal nucleus. Nature 410:1091-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fliege, R., U. I. Flügge, K. Werdan, and H. W. Heldt. 1978. Specific transport of inorganic phosphate, 3-phosphoglycerate and triose phosphates across the inner membrane of the envelope in spinach chloroplasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 502:232-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flügge, U. I. 1999. Phosphate translocators in plastids. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50:27-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibon, Y., O. E. Blasing, N. Palacios-Rojas, D. Pankovic, J. H. Hendriks, et al. 2004. Adjustment of diurnal starch turnover to short days: depletion of sugar during the night leads to a temporary inhibition of carbohydrate utilization, accumulation of sugars and post-translational activation of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in the following light period. Plant J. 39:847-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilson, P. R. 2001. Nucleomorph genomes: much ado about practically nothing. Genome Biol. 2:1022-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould, S. V., M. S. Sommer, K. Hadfi, S. Zauner, R. G. Kroth, and U. G. Maier. Protein targeting into the complex plastid of cryptophytes. J. Mol. Evol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Guillard, R. R. L. 1975. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates, p. 26-60. In W. L. Smith and M. H. Chanley (ed.), Culture of marine invertebrate animals. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Hill, D. R. A., and R. Wetherbee. 1990. Guillardia theta gen. et sp. nov. (Cryptophycae). Can. J. Bot. 68:1873-1876. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huyer, A. 1983. Coastal upwelling in the California current system. Prog. Oceanogr. 12:259-284. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maier, U.-G., S. Douglas, and T. Cavalier-Smith. 2000. The nucleomorph genomes of cryptophytes and chlorarachniophytes. Protist 151:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin, C., and A. M. Smith. 1995. Starch biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7:971-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittag, M., S. Kiaulehn, and C. H. Johnson. 2005. The circadian clock in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. What is it for? What is it similar to? Plant Physiol. 137:399-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Möhlmann, T., O. Batz, U. Maass, and H. E. Neuhaus. 1995. Analysis of carbohydrate transport across the envelope of isolated cauliflower-bud amyloplasts. Biochem. J. 307:521-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhaus, H. E., and M. J. Emes. 2000. Nonphotosynthetic metabolism in plastids. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 51:111-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuhaus, H. E., E. Thom, T. Möhlmann, M. Steup, and K. Kampfenkel. 1997. Characterization of a novel eukaryotic ATP/ADP translocator located in the plastid envelope of Arabidopsis thaliana L. Plant J. 11:73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nisbet, R. E., O. Kilian, and G. I. McFadden. 2004. Diatom genomics: genetic acquisitions and mergers. Curr. Biol. 14:R1048-R1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyvall, P., J. Peloux, H. V. Davies, M. Pedersen, and R. Viola. 1999. Purification and characterization of a novel starch synthase selective for uridine 5′-diphosphate glucose from the red algae Gracilaria tenuistipitata. Planta 209:143-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Passonneau, L. V., and O. H. Lowry. 1993. Enzymatic analysis. A practical approach. Humana Kozak Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 23.Pueschel, C. M. 1990. Cell structure, p. 7-41. In K. M. Cole and R. Sheath (ed.), Biology of red algae. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 24.Rappe, M. S., M. T. Suzuki, K. L. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1998. Phylogenetic diversity of ultraplankton plastid small-subunit rRNA genes recovered in environmental nucleic acid samples from the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:294-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roenneberg, T., and D. Morse. 1993. Two circadian oscillators in one cell. Nature 362:362-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Smith, A. M., K. Denyer, and C. Martin. 1997. The synthesis of the starch granule. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48:67-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoebe, B., and U. G. Maier. 2002. One, two, three: nature's tool box for building plastids. Protoplasma 219:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strzepek, R. F., and P. J. Harrison. 2004. Photosynthetic architecture differs in coastal and oceanic diatoms. Nature 431:689-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stubbs, M. 1981. Inhibitors of the adenine nucleotide translocase. Int. Encyc. Pharm. Ther. 107:283-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Süss, K. H., I. Prokhorenko, and K. Adler. 1995. In situ association of Calvin cycle enzymes, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activase, ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase, and nitrite reductase with thylakoid and pyrenoid membranes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplasts as revealed by immunoelectron microscopy. Plant Physiol. 107:1387-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thyssen, C., R. Schlichting, and C. Giersch. 2001. The CO2-concentrating mechanism in the physiological context: lowering the CO2 supply diminishes culture growth and economises starch utilisation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Planta 213:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Den, K. N., N. Libessart, B. Delrue, C. Zabawinski, A. Decq, et al. 1996. Control of starch composition and structure through substrate supply in the monocellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 271:16281-16287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Dooren, G. G., S. D. Schwartzbach, T. Osafune, and G. I. McFadden. 2001. Translocation of proteins across the multiple membranes of complex plastids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1541:34-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wastl, J., and U. G. Maier. 2000. Transport of proteins into cryptomonads complex plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23194-23198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber, A. P., C. Oesterhelt, W. Gross, A. Brautigam, L. A. Imboden, et al. 2004. EST-analysis of the thermo-acidophilic red microalga Galdieria sulphuraria reveals potential for lipid A biosynthesis and unveils the pathway of carbon export from rhodoplasts. Plant Mol. Biol. 55:17-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zabawinski, C., K. N. Van Den, C. D'Hulst, R. Schlichting, C. Giersch, et al. 2001. Starchless mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii lack the small subunit of a heterotetrameric ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. J. Bacteriol. 183:1069-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziegler, P., and E. Beck. 1989. Biosynthesis and degradation of starch in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 40:95-117. [Google Scholar]