Abstract

African trypanosomes undergo differentiation in order to adapt to the mammalian host and the tsetse fly vector. To characterize the role of a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase homologue, TbMAPK5, in the differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei, we constructed a knockout in procyclic (insect) forms from a differentiation-competent (pleomorphic) stock. Two independent knockout clones proliferated normally in culture and were not essential for other life cycle stages in the fly. They were also able to infect immunosuppressed mice, but the peak parasitemia was 16-fold lower than that of the wild type. Differentiation of the proliferating long slender to the nonproliferating short stumpy bloodstream form is triggered by an autocrine factor, stumpy induction factor (SIF). The knockout differentiated prematurely in mice and in culture, suggestive of increased sensitivity to SIF. In contrast, a null mutant of a cell line refractory to SIF was able to proliferate normally. The differentiation phenotype was partially rescued by complementation with wild-type TbMAPK5 but exacerbated by introduction of a nonactivatable mutant form. Our results indicate a regulatory function for TbMAPK5 in the differentiation of bloodstream forms of T. brucei that might be exploitable as a target for chemotherapy against human sleeping sickness.

Trypanosoma brucei, a unicellular parasite which causes human sleeping sickness, is transmitted between mammals by the tsetse fly. Adaptation of the parasite to the mammalian host and the fly vector entails distinct life cycle stages which differ considerably in morphology, surface coat composition, energy metabolism, and proliferation status (reviewed in reference 23). In the bloodstream and tissue fluids of the mammalian host, T. brucei proliferates as a long slender form and differentiates into a growth-arrested short stumpy form that is preadapted for survival in the fly. When bloodstream forms are taken up during a blood meal by the insect vector, the stumpy form differentiates rapidly to the procyclic (insect) form in the lumen of the fly midgut. The parasite continues its life cycle by progressing through a series of further developmental stages culminating, in the salivary glands of the fly, in differentiation to the metacyclic form which is infective for a new mammalian host (44). Some key features of the differentiation from the long slender to the short stumpy bloodstream form are the partial acquisition of mitochondrial functions (45) and relative resistance to proteases (27, 34) enabling the parasite to survive and differentiate in the inhospitable environment of the fly midgut. In contrast, long slender forms, which are not preadapted for survival in the insect vector, rapidly die upon ingestion by the fly (39). Stumpy forms are also more resistant to acid stress than long slender forms are (27). In addition, they show differences in the synthesis of variant surface glycoproteins (1), in the trafficking of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (10), and in the subcellular localization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C (14), presumably as a prelude to shedding the variant surface glycoprotein coat of the bloodstream form and replacing it with the procyclin coat of the insect midgut form (24, 31, 49).

Differentiation of the slender to the stumpy form is induced by a quorum-sensing mechanism which leads to a limitation of proliferation in the mammalian host (29, 42). The importance of this autoregulatory mechanism is illustrated by the fact that bloodstream form stocks that are unable to differentiate to the stumpy form (known as monomorphic trypanosomes) reach a parasite density that is 1 to 2 orders of magnitude higher than that of their differentiation-competent (pleomorphic) counterparts, often leading to rapid killing of the host (38). Monomorphic trypanosomes have been generated by serial syringe passage between rodents. However, bloodstream form differentiation is not the only determinant of parasite density since this is also controlled by the host immune system (5).

In vitro, differentiation to the short stumpy form is induced by a trypanosome-released factor, termed stumpy induction factor (SIF), which accumulates in conditioned medium (29, 42). Although the identity of SIF remains elusive, we could show that monomorphic bloodstream forms cannot differentiate in response to SIF, even though they still release it (42). Membrane-permeable derivatives of cyclic AMP (cAMP) or specific inhibitors of phosphodiesterases can also induce differentiation to the stumpy form. In agreement with these results, SIF elicits an immediate two- to threefold elevation of the intracellular cAMP content, suggesting that SIF operates through the cAMP pathway, but the underlying signal transduction pathways are unknown (42).

We have started a functional analysis of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases in T. brucei for their roles in proliferation and differentiation. MAP kinases form part of signaling cascades that are activated by extracellular signals or stress and result in phosphorylation of target proteins involved in a variety of biological functions, including differentiation, cell cycle control, and metabolic changes (reviewed in references 15 and 46). There are three major classes of MAP kinases—ERK, p38, and JNK—that are distinguished by the central amino acid in their activation domains (TXY). So far, three ERK homologues have been identified in T. brucei (28). The first kinase to be identified is most closely related to the KSS1 and FUS3 kinases from budding yeast and is named KSS1- and FUS3-related kinase 1 (KFR1) (18). KFR1 activity is decreased by serum starvation and enhanced by gamma interferon, but the function of this kinase is unknown. We recently generated a null mutant of another ERK-like kinase, TbMAPK2 (26). Bloodstream forms of the null mutant were able to grow normally, but when these cells were triggered to differentiate they developed into the procyclic form with markedly delayed kinetics and subsequently underwent cell cycle arrest. The third protein kinase to be identified was TbECK1, which shares features of both ERK and cyclin-dependent kinases (9). Overexpression of a truncated form of TbECK1 gave rise to a slow-growth phenotype in procyclic forms and a high proportion of multinucleate and aberrantly shaped cells. Here we report a functional analysis of a new MAP kinase homologue, TbMAPK5, that is involved in the growth and differentiation of bloodstream forms. Interestingly, deletion of this gene from a differentiation-competent (pleomorphic) stock resulted in a reduction of the peak parasitemia in mice which was due to premature differentiation to the stumpy form.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trypanosomes.

Pleomorphic clone AnTat 1.1 (7, 20) and monomorphic clone MITat 1.2 (strain 221) (6) were used in this study. AnTat 1.1 long slender bloodstream forms were harvested 2.5 days postinfection of NMRI mice, and short stumpy forms were harvested 5 to 6 days postinfection. Bloodstream forms of MITat 1.2 were cultured in HMI 9 (17) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2. Bloodstream forms of AnTat 1.1 were cultured in HMI 9 containing 0.65% SeaPlaque GTG agarose (FMC, Rockland, ME) supplemented with 10% horse serum (40). Conditioned medium was harvested from MITat 1.2 as previously described (42). Procyclic forms of AnTat 1.1 were cultured in SDM-79 (2) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 20 mM glycerol at 27°C (43). Bloodstream form trypanosomes were triggered to differentiate to the procyclic form in modified DTM medium (40) by adding 6 mM cis-aconitate to the culture medium and lowering the incubation temperature to 27°C as described previously (3). Surface expression of EP procyclin was monitored during synchronous differentiation of stumpy forms by flow cytometry with monoclonal antibody TRBP1/247 (30). Stable transformation of AnTat 1.1 procyclic forms was performed essentially as previously described (43), except that transformed cells were supplemented with 5 × 105 untransformed cells per ml of culture medium. Stable transformation of bloodstream forms was performed as previously described (4).

Infection of tsetse flies.

Pupae of Glossina morsitans morsitans were obtained from the International Atomic Energy Agency (Vienna, Austria). Teneral flies were infected with trypanosomes during the first blood meal after emergence (32). The blood meal consisted of 2 × 106 procyclic forms per ml of SDM-79 supplemented with washed horse red blood cells. Infected flies were fed three blood meals per week through artificial membranes. Flies were analyzed for midgut infections by dissection of their midguts. To achieve complete cyclical transmission, we fed flies on anesthetized NMRI mice, which were subsequently monitored for parasitemia.

Infection of mice and diaphorase activity.

The course of chronic infections was determined in NMRI mice inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 long slender forms. Mice were immunosuppressed by intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg of cyclophosphamide per kg of body weight 24 h prior to infection with trypanosomes. Parasitemia was monitored by counting trypanosomes in tail blood diluted with 0.85% ammonium chloride in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.3.

A cytochemical assay for NAD diaphorase activity was performed as previously described (45).

Constructs for deletion or ectopic expression of TbMAPK5.

Two promoterless constructs (pTbMAPK5koHYGr and pTbMAPK5koBLEr) were designed to delete both alleles of TbMAPK5 sequentially by homologous recombination. Each construct contains sequences flanking the open reading frame (ORF) of TbMAPK5, including the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions and intergenic sequences. The 3′-flanking sequence was amplified from genomic DNA of AnTat 1.1 with primers 5′TbTDY-BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCCTCCGACTAGTTGATTAAG-3′) and 3′TbTDY-XbaI (5′-GCTCTAGACCACAACACTCAAAATGACC-3′) and cloned between the BamHI and XbaI sites of pBS-PHLEO (32). The underlined sequences are restriction sites that were introduced to facilitate cloning. The 5′-flanking sequence of TbMAPK5 was amplified with primers 5′TbTDY-KpnI (5′-CGGGGTACCGGTCGTGACTTTATG-3′) and 5′TbTDY-HindIII (5′-CCCAAGCTTTACACGCGCTAACACAGG-3′) and cloned between the KpnI and HindIII sites of the derived construct to generate pTbMAPK5koBLEr. The phleomycin resistance gene was released from this construct by cleavage with HindIII and BamHI and replaced with the hygromycin resistance gene released from pBS-hyg (32), giving rise to pTbMAPK5koHYGr. For stable transformation, knockout constructs were linearized by cleavage with KpnI and XbaI.

For ectopic re-expression of TbMAPK5 in the procyclin locus, plasmid pGAPRONE-ΔLII-TbTDY-PAC was constructed. The complete ORF of the gene was amplified by PCR with primers TDYf-HindIII (5′-CCCAAGCTTATGGTAACAGCAAATGGC-3′) and TDYr-BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCTTACTGATAGTGCTGAATC-3′) with genomic DNA from AnTat 1.1 as the template. The PCR product was cloned between the HindIII and BamHI sites of a derivative of the pGAPRONE-ΔLII vector (12) containing the puromycin resistance gene. For construction of pGAPRONE-MAPK5(T207A, Y209F), a fragment encompassing the activation domain of TbMAPK5 was amplified with primers TDYmut (5′-GATACCAACGCGTGACTACGAAATCCGCGAGATCAACTGGTTCCTG −3′) and TDYf-EcoRI (5′-GGGAATTCATGGTAACAGCAAATGGCT-3′) and cloned between the HincII and MluI sites of pGAPRONE-MAPK5. The double-underlined bases are mutations introduced into the primer sequence. For stable transformation, both add-back constructs were linearized by cleavage with KpnI and NotI.

Nucleic acid analysis.

Northern blot and Southern blot analyses were performed by standard procedures (33). For Northern blotting, a multiprime-labeled probe used for hybridization was generated from the coding region of TbMAPK5. An oligonucleotide which hybridizes to the 18S rRNA (11) was used as an internal control for sample loading. Hybridization signals were quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). For Southern blotting, digoxigenin-labeled probes were used according to the manufacturer's (Roche) instructions.

RESULTS

TbMAPK5 contains the signature of MAP kinases.

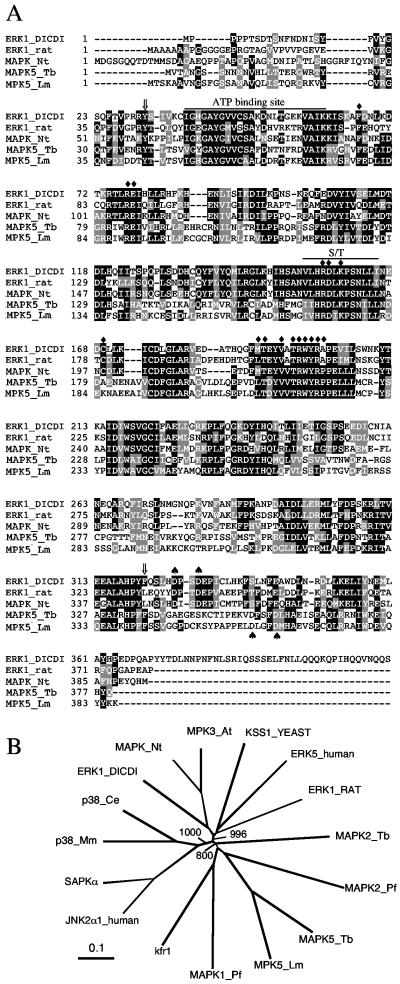

BLAST searches of the T. brucei genome database (www.ebi.ac.uk/parasites/parasite-genome.html) with sequences from MAP kinases from plants allowed the identification of nine MAP kinase homologues in T. brucei, three of which have been described previously (9, 18, 26). One of the kinases, TbMAPK5 (accession number Tb927.6.4220), which has not yet been investigated, contains a TDY sequence motif in the activation domain. This protein kinase gene maps to chromosome 6 and contains an ORF of 1,140 bp encoding a putative protein with a calculated molecular mass of 43.6 kDa. By profile database searches, all conserved amino acid residues that define the catalytic domain of protein kinases (16) were identified in a region encompassing the sequences from amino acid positions 38 to 335 (Fig. 1A). The signature motif of serine/threonine protein kinases (16) was also found in this domain. In addition, all amino acid residues diagnostic for MAP kinases, which are absent from all other classes of protein kinases, including the related cyclin-dependent kinases (8, 19), are clearly recognizable (indicated by black diamonds in Fig. 1A). A potential common docking domain involved in protein-protein interactions (36) is present in the C-terminal part of the protein. Consistent with these results, BLAST searches of databases revealed that TbMAPK5 is most closely related to MAP kinases from other organisms. The protein shares 59% amino acid sequence identity with MPK5 from Leishmania mexicana (47), 37 to 38% identity with MAP kinases from plants, and 33 to 34% identity with MAP kinases from mammals.

FIG. 1.

TbMAPK5 is related to MAP kinases. (A) The amino acid sequence of TbMAPK5 is displayed by Clustalx1.82 alignment (37) with MAP kinases from Dictyostelium discoideum (ERK1_DICDI, EMBL accession no. P42525) (13), Rattus norvegicus (ERK1_rat, EMBL accession no. P21708) (22), Nicotiana tabacum (MAPK_Nt, EMBL accession no. U94192.1) (48), and L. mexicana (MPK5_Lm, EMBL accession no. AJ93283) (47). Identical and conserved amino acids are shaded black and gray, respectively. The start and the end of the catalytic domain are indicated by vertical arrows, sequences highly diagnostic for MAP kinases (8, 19) are indicated by black diamonds, and conserved amino acids of the common docking domain are indicated by spades. Domains with known functions, including the ATP binding site and a domain diagnostic for serine/threonine kinases (S/T), are overlined. (B) Radial phylogenetic tree of the MAP kinases described above, together with MPK3 (MP_114433) from Arabidopsis thaliana, KSS1 (M26398) from yeast, ERK5 (Q13164) and JNK2α1 (AAC50606) from humans, SAPKα (P92208) from Drosophila melanogaster, p38 (Q9Z1B7) from mice, KFR1 (18) and MAPK2 (26) from T. brucei, and MAPK1 (NC_702183) and MAPK2 (JC5153) from Plasmodium falciparum were constructed with the TreeView software (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/rod.html). Bootstrap values indicating the number of occurrences of branch points during 1,000 replications are given for the three primary branches consisting of the ERK subgroup, stress-activated protein kinases, and MAP kinases from protozoa.

The central amino acid in the activation domain of TbMAPK5 is aspartic acid instead of the glutamic acid, proline, or glycine normally found in MAP kinases of higher eukaryotes. To investigate which subgroup of MAP kinases is most closely related to TbMAPK5, a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Fig. 1B). In higher eukaryotes, members of the JNK and p38 group map to the same primary branch while members of the ERK group, which are more distantly related, map to a separate branch (19). In contrast, all protozoan MAP kinases, including TbMAPK5, map to a third primary branch. Thus, TbMAPK5 belongs to a distinct class of MAP kinases.

TbMAPK5 is not an essential gene.

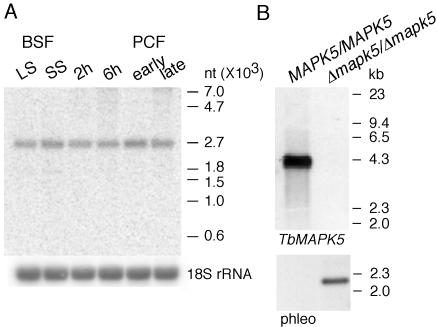

In order to generate a TbMAPK5 null mutant, it was important to determine the genomic organization of TbMAPK5 and to investigate in which stage of the life cycle the protein kinase is expressed. Southern blot analyses revealed that TbMAPK5 is a single-copy gene (data not shown). By Northern blot analysis, we could show that TbMAPK5-specific mRNA is expressed at similar levels in all of the life cycle stages that are amenable to in vitro culture (Fig. 2A). In addition, no change in the steady-state level of mRNA was observed during synchronous differentiation of the short stumpy bloodstream form to the procyclic form. To monitor protein levels, two rabbits were immunized against recombinant TbMAPK5. Although both antisera were able to recognize recombinant TbMAPK5 protein, they were not able to recognize any proteins in trypanosomal extracts, suggesting that this protein kinase is only expressed at a very low level (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Nucleic acid analyses of TbMAPK5. (A) Steady-state level of TbMAPK2 mRNA. Equal amounts of total RNA (10 μg) extracted from long slender (LS) and short stumpy (SS) bloodstream forms (BSF), synchronously differentiating forms 2 h and 6 h after triggering of differentiation, and early and late procyclic forms (PCF) cultured in the presence or absence of glycerol were loaded. Expression was analyzed by Northern blotting with a radiolabeled, TbMAPK5-specific probe (top). Hybridization signals were quantified with a PhosphorImager and normalized to the 18S rRNA (bottom). The values below indicate the relative amounts of TbMAPK5-specific mRNA in the different stages. nt, nucleotides. (B) Southern blot analysis of a TbMAPK5 null mutant of monomorphic clone MITat 1.2. Genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled probes from the ORF of TbMAPK5 (top) or the phleomycin resistance gene (phleo, bottom).

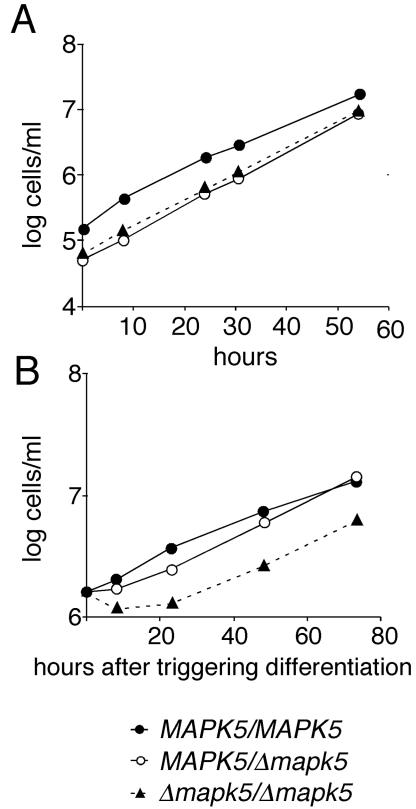

Promoterless targeting constructs were designed containing antibiotic resistance genes cloned between sequences flanking the ORF of TbMAPK5 to specifically replace the TbMAPK5 coding region with a resistance gene. Two successive rounds of transformation and selection were performed to delete both copies of TbMAPK5. To investigate whether TbMAPK5 is involved in proliferation or differentiation of bloodstream to procyclic forms, we first generated a null mutant in bloodstream forms of monomorphic clone MITat 1.2. The advantage of using this cell line is that it can be easily kept in culture (25) and can be analyzed for the ability to differentiate to the procyclic form (31). Sequential rounds of transformation were performed with constructs pTbMAPK5koHYGr and pTbMAPK5koBLEr, and one null mutant clone (Δmapk5::HYG/Δmapk5::BLE no. 2) was selected for further analysis. Southern blot analysis confirmed that both copies of TbMAPK5 were deleted from this clone and that both resistance genes had integrated correctly (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Bloodstream forms of the null mutant had a population doubling time indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Fig. 3A). Bloodstream forms can be triggered to differentiate to the procyclic form in vitro by adding cis-aconitate to the culture medium and lowering the incubation temperature to 27°C (3). To monitor differentiation, the appearance of procyclin on the surface of trypanosomes was analyzed by immunofluorescence. No difference in the kinetics of differentiation was observed between the wild type and the null mutant (data not shown). In contrast to the wild type, however, a relatively large proportion of the null mutant population died during differentiation, as indicated by a 50% lower parasite density relative to that of the wild type 8 h after triggering of differentiation (Fig. 3B). The ability to differentiate normally was restored in the add-back mutant (data not shown). No difference in the growth rate of established procyclic forms was observed between the wild type and the null mutant (Fig. 3B). Thus, TbMAPK5 is not essential for proliferation of bloodstream or procyclic forms of monomorphic stocks.

FIG. 3.

The TbMAPK5 null mutant of monomorphic clone MITat 1.2 is able to grow normally. (A) Population growth of bloodstream form trypanosomes of the wild type (MAPK5/MAPK5), the heterozygous mutant (MAPK5/Δmapk5::HYG), and the null mutant(Δmapk5::HYG/Δmapk5::BLE). (B) Population growth upon triggering of differentiation (with cis-aconitate) of the same clones as above. Cells were diluted at daily intervals to ensure logarithmic growth. Population growth was calculated as cell density multiplied by the cumulative dilution factors.

Generation of TbMAPK5 null mutants in pleomorphic trypanosomes.

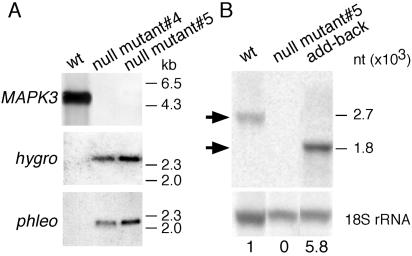

Monomorphic trypanosomes are unable to differentiate to the stumpy form and to complete the life cycle in the tsetse fly. To investigate whether TbMAPK5 is involved in the differentiation to the stumpy form or during development in the fly, we generated a null mutant in the fly-transmissible pleomorphic strain AnTat 1.1. A strategy similar to that described above was used to generate null mutants from procyclic forms of this clone. Procyclic forms can lose their ability for cyclical transmission upon long-term cultivation (R. Brun, personal communication). To obtain fly-transmissible clones, freshly differentiated procyclic forms were used for electroporation and after each round of transformation and selection they were transmitted through tsetse flies. The first round of transformation was performed with pTbMAPK5koHYGr and selection with hygromycin. One clone was analyzed by Southern blotting, demonstrating that the targeting construct had integrated correctly and had replaced one copy of TbMAPK5 (data not shown). Following fly transmission, this clone was subjected to a second round of transformation with pTbMAPK5koBLEr and selection with phleomycin. Two independent clones (Δmapk5::HYG/Δmapk5::BLE no. 4 and no. 5) were chosen for further analysis. Northern and Southern blot analyses confirmed that both copies of TbMAPK5 were deleted from these mutants (Fig. 4A and B and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of TbMAPK5 null mutants and an add-back mutant of pleomorphic clone AnTat 1.1. (A) Southern blot analysis of the wild type (wt) and two independent TbMAPK5 null mutant clones. Genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled probes from the ORF of TbMAPK5, the hygromycin resistance gene (hygro), or the phleomycin resistance gene (phleo). (B) Northern blot analysis. Total RNA was extracted from bloodstream form trypanosomes of the wild type, the null mutant, and the add-back mutant and hybridized with radiolabeled sequences from TbMAPK5 (top) or, as a control for sample loading, with an 18S rRNA-specific probe (bottom). Hybridization signals were quantified with a phosphorimager and normalized to the 18S rRNA. TbMAPK5-specific hybridization signals of the wild type (2.7 kb) and the add-back mutant (1.8 kb) are indicated by arrows. Values below the panel indicate relative amounts of TbMAPK5-specific mRNA. nt, nucleotides.

TbMAPK5 controls the growth of bloodstream forms of T. brucei.

Procyclic forms of both null mutant clones of the pleomorphic stock were able to grow normally in culture and to establish midgut infections in the tsetse fly vector. Three weeks postinfection, flies were fed on anesthetized NMRI mice and the ensuing parasitemias were monitored in tail blood. Both null mutant clones infected mice, demonstrating that they had not lost their ability for cyclical transmission through the fly. In marked contrast to the wild type and the heterozygous mutant, however, both null mutant clones were unable to reach a high parasite density in mice. To confirm that this phenotype was due to TbMAPK5 deletion, an add-back mutant was constructed in which one copy of TbMAPK5 was reintroduced into procyclic forms of null mutant clone no. 5 under the control of the procyclin promoter. Again, trypanosomes were cyclically transmitted through tsetse flies, followed by mouse infections in order to obtain bloodstream forms of the add-back mutant. Southern blot analyses confirmed that TbMAPK5 had integrated into one of the procyclin loci (data not shown). In bloodstream forms, the level of TbMAPK5-specific mRNA in the add-back mutant was 5.8-fold higher than that of the wild type as indicated by Northern blotting (Fig. 4B).

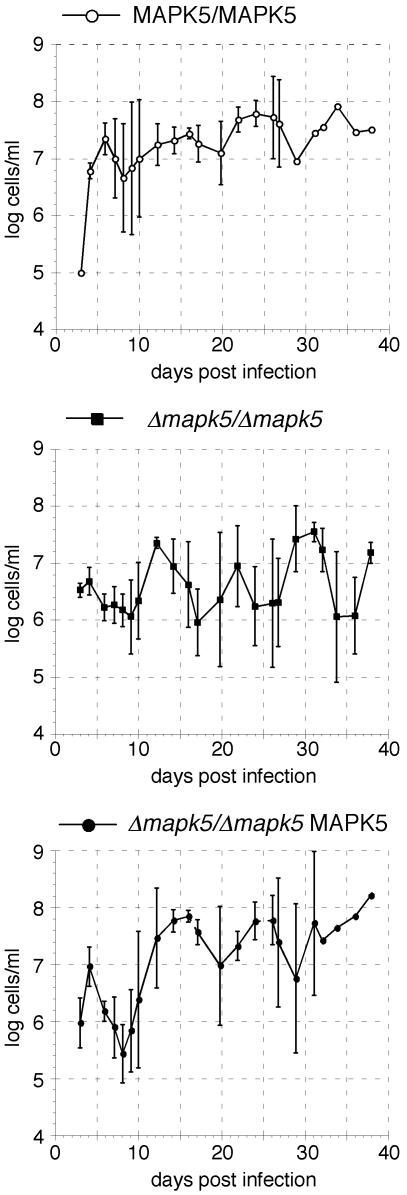

In a first experiment, the wild type, null mutant clone no. 5, and the add-back mutant derived from this clone were compared during the course of chronic infections of immunocompetent inbred NMRI mice. Infections with pleomorphic bloodstream forms are characterized by a first peak of parasitemia, followed by a trough at the onset of the immune response and recrudescence of a new, antigenically distinct parasite population to a second peak, followed by a fairly level plateau phase (38). The courses of infection of all three clones were similar (Fig. 5). However, there was a clear difference in the peak parasitemias. The maximal density reached by the wild type, calculated from the first three peaks of infection (6, 16, and 24 days postinfection), was log10 7.5 ± 0.3 cells/ml. The maximal density reached by the null mutant (log10 7.0 ± 0.5 cells/ml, calculated from the maxima after 4, 12, and 22 days) was threefold lower than that obtained for the wild type (P = 0.01). The ability to reach a high parasite density was completely restored in the add-back mutant. This clone reached a density of log10 7.5 ± 0.5 cells/ml, as calculated from the peak parasitemias after 4, 16, and 24 days postinfection. Thus, the reduced level of parasitemia achieved by the null mutant was due to TbMAPK5 deletion.

FIG. 5.

Course of parasitemia of the wild type, null mutant, and add-back mutant of AnTat 1.1 during chronic infections of immunocompetent mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 × 105 long slender bloodstream forms, and the ensuing parasitemia was monitored from tail blood. The mean ± the standard deviation of three mice is presented.

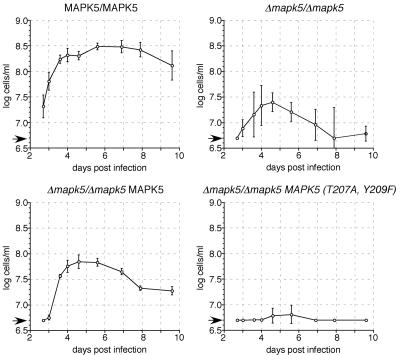

Null mutant cells might be less virulent because of a reduced rate of antigenic variation or, alternatively, because of a reduced rate of proliferation. A third possibility is that the null mutant undergoes differentiation to the stumpy form more readily, resulting in inhibition of growth at a lower parasite density. To discriminate among these possibilities, the same growth experiment was repeated as described above with NMRI mice that had been immunosuppressed by treatment with cyclophosphamide prior to injection with trypanosomes (Fig. 6). The maximal density reached by the wild type in immunocompromised mice (log10 8.5 ± 0.1 cells/ml) was ∼10-fold higher than that in immunocompetent mice (log10 7.5 ± 0.3 cells/ml), suggesting that in the latter case the maximum level of parasitemia was limited by the humoral response of the host (Fig. 6). In contrast, the maximal density obtained for the null mutant clone in immunosuppressed mice (log10 7.3 ± 0.2 cells/ml) was only marginally higher than that in immunocompetent mice (log10 7.0 ± 0.5 cells/ml), suggesting that limitation of growth was not due to the host immune response. In immunocompromised mice, the peak parasitemia reached by the wild type was 16-fold higher than that reached by the null mutant (P < 0.001). The peak parasitemia reached by the add-back mutant was intermediate between those reached by the wild type and the null mutant (log10 7.8 ± 0.1 cells/ml), suggesting partial rescue of the phenotype (Fig. 6). From these results, we conclude that the reduced virulence of the null mutant was unlikely to be due to a reduced rate of antigenic variation. To investigate whether bloodstream forms depend on activated TbMAPK5, a mutant was constructed in which the T207 and Y209 residues of the activating phosphorylation sites of TbMAPK5 were replaced with alanine and phenylalanine, respectively. This mutant gene was introduced into a procyclin locus of the TbMAPK5 null mutant. Two independent clones in which the mutated TbMAPK5 gene had integrated correctly (data not shown) were selected for further investigation. Northern blot analysis confirmed that the mutated gene was expressed in these clones at a level similar to that in the add-back mutant (data not shown). Both Δmapk5/Δmapk5 MAPK5(T207A, Y209F) clones were transmitted through tsetse flies and analyzed for infections in immunosuppressed mice. The maximal parasite density reached by either of these clones was 2 orders of magnitude lower than that of the wild type and 1 order of magnitude lower than that of the null mutant during infections of immunocompromised mice (Fig. 6). We conclude from these results that TbMAPK5 needs to be phosphorylated in order to rescue the phenotype. Moreover, the reduced virulence of the Δmapk5/Δmapk5 MAPK5(T207A, Y209F) clones compared to the null mutant suggests that mutant TbMAPK5 might adversely affect other (MAP) kinases by competitive inhibition, a phenomenon that has also been observed in other cell systems (21).

FIG. 6.

Course of chronic infections of immunocompromised mice. Mice were treated with cyclophosphamide 24 h prior to infection with 1 × 105 trypanosomes. The mean ± the standard deviation of four mice is presented. Cell numbers below the detection limit (indicated by arrows) were set to 5 × 106 cells/ml.

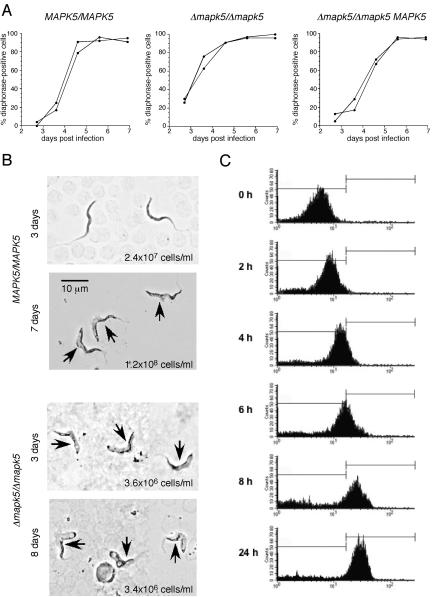

To investigate whether null mutant cells undergo differentiation at a reduced parasite density, trypanosomes were analyzed for mitochondrial diaphorase activity, which is considered to be a specific marker for intermediate (a transitional stage between slender and stumpy forms) and fully differentiated stumpy forms (45). During the course of chronic infections of immunocompromised mice, the kinetics of appearance of diaphorase-positive cells of the null mutant population was accelerated by ∼24 h relative to that of the wild type or the add-back mutant and occurred at a parasite density that was significantly lower than that of the wild type (Fig. 7A and B). These results indicate that the reduced virulence of the null mutant correlated with an increased rate of differentiation to the stumpy form. Consistent with these results, a high percentage of the population of both TbMAPK5(T207A, Y209F) mutant clones were diaphorase positive (data not shown). One week postinfection, wild-type cells had intermediate morphology while null mutant cells were fully developed short stumpy forms, supporting the finding that the latter had undergone accelerated differentiation (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Null mutant cells undergo differentiation at a reduced parasite density. (A) Percentage of diaphorase-positive cells during the time course of chronic infections of immunocompromised mice. Two independent experiments are shown. Figures 6 and 7 are from the same set of experiments. (B) Diaphorase activity of the wild type and the null mutant harvested 3 days or 7 to 8 days postinfection of immunocompromised mice. Arrows indicate diaphorase-positive cells (intermediate and stumpy forms). At least 100 cells were counted per sample. (C) Synchronous differentiation of stumpy forms of the null mutant. Stationary-phase bloodstream forms were harvested from the blood of infected mice 4 days postinfection and triggered to differentiate to the procyclic form. The appearance of EP procyclin on the surface of trypanosomes was monitored by flow cytometry with monoclonal antibody TRBP1/247 (30).

A functional marker of stumpy forms is their ability to differentiate synchronously to procyclic forms (24, 49). Stationary-phase bloodstream forms of the null mutant were harvested 4 days postinfection and triggered to differentiate to the procyclic form by addition of cis-aconitate to the culture medium and shifting of the incubation temperature to 27°C. The appearance of EP procyclin on the surface of trypanosomes was monitored by flow cytometry with a monoclonal antibody. These results demonstrated that null mutant cells were able to differentiate synchronously (Fig. 7C) with kinetics similar to those of wild-type cells (42; data not shown). No cell death was observed during the time course of the experiment. Thus, the phenotype observed during the differentiation of the monomorphic clone seems to be strain specific.

Null mutant cells differentiate at low density in culture.

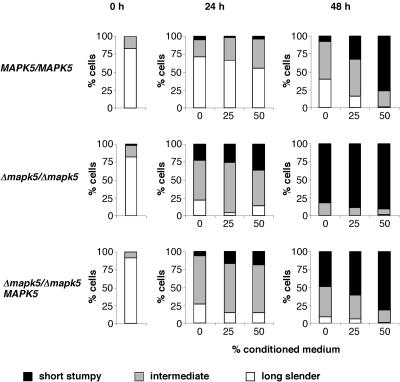

Since TbMAPK5 appears to be a negative regulator of bloodstream form differentiation, we predicted that the null mutant would exhibit an increased sensitivity to SIF. The wild type, the null mutant, and the add-back mutant were seeded in culture at a density of 1.4 × 104 cells/ml, and the percentages of intermediate and stumpy forms (both of which are diaphorase positive) were determined after 24 and 48 h. Figure 8 demonstrates that the percentage of stumpy forms was significantly higher in the null mutant population than in the wild-type or the add-back mutant population during the course of the experiment (Fig. 8, no conditioned medium added). Consistent with the results obtained during mouse infections, the density reached by the wild type was markedly higher than that attained by the null mutant. The wild-type culture increased in density by a factor of ∼40 within a period of 48 h before it reached the stationary phase. The majority of the wild-type population was diaphorase negative after 24 h but became diaphorase positive after 48 h (Fig. 8, no conditioned medium added). At that time point, most diaphorase-positive cells had the morphology characteristic of the intermediate form. In contrast to the wild type, the null mutant was barely able to divide. In addition, the majority of this population showed intermediate morphology after 24 h and stumpy morphology after 48 h. Again, the differentiation phenotype was partially restored in the add-back mutant. Addition of conditioned medium to the cultures enhanced the kinetics of differentiation of the wild type or the add-back mutant but had virtually no effect on the null mutant clone. Thus, differentiation of this clone is almost maximally induced in the absence of conditioned medium.

FIG. 8.

The null mutant differentiates at low cell density in vitro. Bloodstream forms of the wild type, null mutant, and add-back mutant were harvested from mouse blood 3 days postinfection and subjected to in vitro culture in the presence or absence of conditioned medium from a bloodstream form culture of monomorphic line MITat 1.2. After 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h, aliquots were removed from the cultures and analyzed for cell morphology and diaphorase activity. At least 40 cells of the population harvested from mouse blood (0 h) and at least 100 cells of the population that had been cultured for 24 or 48 h, respectively, were counted per sample. The percentages of long slender (diaphorase negative, slender morphology), intermediate (diaphorase positive, slender or intermediate morphology), and stumpy forms (diaphorase positive, stumpy morphology) are indicated.

DISCUSSION

TbMAPK5 null mutants were constructed in two life cycle stages: bloodstream forms from a monomorphic stock and procyclic forms from a pleomorphic, fly-transmissible stock. The bloodstream form null mutant from the monomorphic stock had a population doubling time indistinguishable from that of the parental line and was able to differentiate to the procyclic form. The procyclic form null mutant from the pleomorphic stock was also able to proliferate normally in culture and could be cyclically transmitted by tsetse, indicating that TbMAPK5 is not essential for other life cycle stages of the fly. In addition, this null mutant was able to infect immunocompetent mice but the peak parasitemia was threefold lower than that of the wild type. The difference in parasite density between the wild type and the null mutant increased to 16-fold in immunosuppressed mice, mainly owing to a 10-fold increase in the peak parasitemia of the wild type. In contrast, the density of the null mutant increased only marginally. This is in agreement with the concept that, under normal circumstances, both the humoral immune response of the host and differentiation to the stumpy form limit parasite density. In the case of the null mutant, however, the host immune response did not appear to play a significant role since a similar maximal density was obtained in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed mice and differentiation to the stumpy form occurred at a much lower density. In addition, the null mutant differentiated more readily to the stumpy form in culture. The growth and differentiation phenotypes in mice and in culture were partially restored by integration of an ectopic copy of TbMAPK5 into a procyclin locus. Partial rescue of the phenotype by an ectopic copy of a MAP kinase in a procyclin locus was previously observed for TbMAPK2 (26) and might be a consequence of different regulatory sequences in the mRNA. When expressed from the same locus, a mutant form of TbMAPK5 exacerbated the phenotype rather than rescuing it, demonstrating that TbMAPK5 needs to be phosphorylated in order to be activated.

In contrast to pleomorphic stocks, monomorphic stocks are refractory to the differentiation signal (42). Thus, the finding that bloodstream form null mutants from the monomorphic stock were able to grow normally is in agreement with our finding that TbMAPK5 is directly involved in bloodstream form differentiation. To investigate whether activation of TbMAPK5 was mediated by MAP kinase kinases, we cloned four MAP kinase kinase homologues from T. brucei and analyzed three of them for interaction with TbMAPK5 in the yeast two-hybrid system. In addition, we screened a cDNA library derived from bloodstream forms of AnTat 1.1 with TbMAPK5 as bait in the yeast two-hybrid system. However, in neither of these cases were we able to identify proteins that are able to interact with TbMAPK5 (S. Morand and E. Vassella, unpublished results) and thus it remains to be shown whether this protein kinase operates in a classical MAP kinase pathway.

When monomorphic bloodstream forms were triggered to differentiate to the procyclic form, a relatively high proportion of the population underwent cell death. This might suggest that TbMAPK5 is also involved in a later differentiation step. In contrast to this result, however, the null mutant from the pleomorphic stock was able to differentiate efficiently to the procyclic form. The apparent discrepancy between these results might be explained by the presence of redundant pathways involved in differentiation of pleomorphic trypanosomes, whereas the pathway operating through TbMAPK5 might be important in the monomorphic strain.

There are several ways in which TbMAPK5 might control bloodstream form differentiation. It might lower the sensitivity to SIF by reducing the expression or binding affinity of its receptor or by interfering with the downstream cAMP signaling pathway (42). All of these hypotheses would be compatible with our observations that monomorphic bloodstream forms show no phenotype since these cells are already refractory to SIF. The concentration of SIF in conditioned medium derived from a bloodstream form culture of the null mutant was similar to that in medium from a wild-type culture (G. Burkard, unpublished results), excluding the possibility that TbMAPK5 acts as a negative regulator by lowering the production of SIF. In many cell systems, cAMP and MAP kinase signaling exert antagonistic effects on cell proliferation (35). One function of MAP kinases is to promote cell cycle progression in response to growth factor activation, but this can be inhibited by the cAMP pathway. Thus, an alternative function of TbMAPK5 might be to promote cell cycle progression of bloodstream forms, while SIF, which induces cell cycle arrest (42), might lead to inactivation of this kinase. Since the null mutant is still able to divide, however, this suggests that other kinases besides TbMAPK5 are involved in cell cycle progression. The add-back mutant expressing the inactive mutant form [Δmapk5/Δmapk5 MAPK5(T207A, Y209F)] gave rise to a much stronger phenotype than the null mutant, implying that it interferes with the action of other kinases. Deletion of another protein kinase, zinc finger kinase (ZFK), gave rise to a differentiation phenotype in vitro which was also specific for the pleomorphic line (41). This suggests that ZFK and TbMAPK5 might be involved in similar processes. However, the in vitro phenotype of the ZFK null mutant was much milder than that of the TbMAPK5 null mutant and no phenotype was observed during mouse infection. We have shown previously that TbMAPK2 promotes cell cycle progression of procyclic forms (26). Hence, TbMAPK2 and TbMAPK5 might be counterparts for the control of proliferation of procyclic and bloodstream forms, respectively. In contrast to the TbMAPK2 null mutant, however, which gave rise to a non-phase-specific cell cycle arrest, the TbMAPK5 null mutant from the pleomorphic stock has presumably undergone arrest in the G1/G0 phase in which the stumpy form is held.

Once a trypanosome differentiates to the nondividing stumpy form, it has a limited life span of a few days (38). The molecular mechanisms underlying differentiation may be exploitable for the development of new drugs against sleeping sickness. Our results indicate that TbMAPK5 might be an interesting drug target since it is an important virulence factor in the mammalian host. In addition, this protein kinase differs considerably in sequence from mammalian MAP kinases. By performing high-throughput screens, specific inhibitors of TbMAPK5 that discriminate between host and parasite enzymes might be identified and used for the treatment of sleeping sickness.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Dobbelaere for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31-063987) and the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation to I.R. and by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31-64900) and the Hans Sigrist Foundation to E.V.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiguet-Vercher, A., D. Perez-Morga, A. Pays, P. Poelvoorde, H. Van Xong, P. Tebabi, L. Vanhamme, and E. Pays. 2004. Loss of the mono-allelic control of the VSG expression sites during the development of Trypanosoma brucei in the bloodstream. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1577-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brun, R., and M. Schönenberger. 1979. Cultivation and in vitro cloning of procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Acta Trop. 36:289-292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brun, R., and M. Schönenberger. 1981. Stimulating effect of citrate and cis-aconitate on the transformation of Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms to procyclic forms in vitro. Z. Parasitenkd. 66:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carruthers, V. B., L. H. van der Ploeg, and G. A. Cross. 1993. DNA-mediated transformation of bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:2537-2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross, G. A. 1996. Antigenic variation in trypanosomes: secrets surface slowly. Bioessays 18:283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross, G. A. M., and J. C. Manning. 1973. Cultivation of Trypanosoma brucei sspp. in semi-defined and defined media. Parasitology 67:315-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delauw, M.-F., E. Pays, M. Steinert, D. Aerts, N. Van Meirvenne, and D. Le Ray. 1985. Inactivation and reactivation of a variant-specific antigen gene in cyclically transmitted Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 4:989-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorin, D., P. Alano, I. Boccaccio, L. Cicéron, C. Dörig, R. Sulpice, D. Parzy, and C. Dörig. 1999. An atypical mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) homologue expressed in gametocytes of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29912-29920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis, J., M. Sarkar, E. Hendriks, and K. Matthews. 2004. A novel ERK-like, CRK-like protein kinase that modulates growth in Trypanosoma brucei via an autoregulatory C-terminal extension. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1487-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engstler, M., and M. Boshart. 2004. Cold shock and regulation of surface protein trafficking convey sensitization to inducers of stage differentiation in Trypanosoma brucei. Genes Dev. 18:2798-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flück, C., J. Y. Salomone, U. Kurath, and I. Roditi. 2003. Cycloheximide-mediated accumulation of transcripts from a procyclin expression site depends on the intergenic region. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 127:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furger, A., N. Schürch, U. Kurath, and I. Roditi. 1997. Elements in the 3′ untranslated region of procyclin mRNA regulate expression in insect forms of Trypanosoma brucei by modulating RNA stability and translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4372-4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaskins, C., M. Maeda, and R. A. Firtel. 1994. Identification and functional analysis of a developmentally regulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase gene in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6997-7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruszynski, A. E., A. DeMaster, N. M. Hooper, and J. D. Bangs. 2003. Surface coat remodeling during differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 278:24665-24672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan, K.-L. 1994. The mitogen activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway: from the cell surface to the nucleus. Cell. Signal. 6:581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanks, S. K., A. M. Quinn, and T. Hunter. 1988. The protein kinase family: conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains. Science 241:42-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirumi, H., and K. Hirumi. 1989. Continuous cultivation of Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms in a medium containing a low concentration of serum protein without feeder cell layers. J. Parasitol. 75:985-989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua, S. B., and C. C. Wang. 1997. Interferon-gamma activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase, KFR1, in the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10797-10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kültz, D. 1998. Phylogenetic and functional classification of mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases. J. Mol. Evol. 46:571-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Ray, D., J. D. Barry, C. Easton, and K. Vickerman. 1977. First tsetse fly transmission of the “AnTat” serodeme of Trypanosoma brucei. Ann. Soc. Belge Med. Trop. 57:369-381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madhani, H. D., C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1997. MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell 91:673-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marquardt, B., and S. Stabel. 1992. Sequence of a rat cDNA encoding the ERK1-MAP kinase. Gene 120:297-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews, K. R. 2005. The developmental cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell Sci. 118:283-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews, K. R., and K. Gull. 1994. Evidence for an interplay between cell cycle progression and the initiation of differentiation between life cycle forms of African trypanosomes. J. Cell Biol. 125:1147-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch, R., E. Vassella, P. Burton, M. Boshart, and J. D. Barry. 2004. Transformation of monomorphic and pleomorphic Trypanosoma brucei. Methods Mol. Biol. 262:53-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller, I. B., D. Domenicali-Pfister, I. Roditi, and E. Vassella. 2002. Stage-specific requirement of a mitogen-activated protein kinase by Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3787-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan, D. P., S. Rolin, J. R. Rodriguez, J. Van Den Abbeele, and E. Pays. 2000. Slender and stumpy bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei display a differential response to extracellular acidic and proteolytic stress. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:18-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons, M., E. A. Worhtey, P. N. Ward, and J. C. Mottram. 2005. Comparative analysis of the kingdoms of three pathogenic trypanosomatids: Leishmania major, Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi. BMC Genomics 6:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reuner, B., E. Vassella, B. Yutzy, and M. Boshart. 1997. Cell density triggers slender to stumpy differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream forms in culture. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 90:269-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson, J. P., R. P. Beecroft, D. L. Tolson, M. K. Liu, and T. W. Pearson. 1988. Procyclin: an unusual immunodominant glycoprotein surface antigen from the procyclic stage of African trypanosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 31:203-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roditi, I., H. Schwarz, T. W. Pearson, R. P. Beecroft, M. K. Liu, J. E. Richardson, H.-J. Bühring, J. Pleiss, R. Bülow, R. O. Williams II, and Peter Overath. 1989. Procyclin gene expression and loss of the variant surface glycoprotein during differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell Biol. 108:737-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruepp, S., A. Furger, U. Kurath, C. K. Renggli, A. Hemphill, R. Brun, and I. Roditi. 1997. Survival of Trypanosoma brucei in the tsetse fly is enhanced by the expression of specific forms of procyclin. J. Cell Biol. 137:1369-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Sbicego, S., E. Vassella, U. Kurath, B. Blum, and I. Roditi. 1999. The use of transgenic Trypanosoma brucei to identify compounds inducing the differentiation of bloodstream forms to procyclic forms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 104:311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stork, P. J., and J. M. Schmitt. 2002. Crosstalk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation. Trends Cell Biol. 12:258-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanoue, T., and E. Nishida. 2003. Molecular recognitions in the MAP kinase cascades. Cell. Signal. 15:455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner, C. M., N. Aslam, and C. Dye. 1995. Replication, differentiation, growth and the virulence of Trypanosoma brucei infections. Parasitology 111:289-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner, C. M., J. D. Barry, and K. Vickerman. 1988. Loss of variable antigen during transformation of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense from bloodstream to procyclic forms in the tsetse fly. Parasitol. Res. 74:507-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vassella, E., and M. Boshart. 1996. High molecular mass agarose matrix supports growth of bloodstream forms of pleomorphic Trypanosoma brucei strains in axenic culture. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 82:91-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassella, E., R. Krämer, C. M. R. Turner, M. Wankell, C. Modes, M. van den Bogaard, and M. Boshart. 2001. A novel protein kinase with PX and FYVE-related domains controls the rate of differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 41:33-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vassella, E., B. Reuner, B. Yutzy, and M. Boshart. 1997. Differentiation of African trypanosomes is controlled by a density sensing mechanism which signals cell cycle arrest via the cAMP pathway. J. Cell Sci. 110:2661-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vassella, E., J. van Den Abbeele, P. Bütikofer, C. Renggli Kunz, A. Furger, R. Brun, and I. Roditi. 2000. A major surface glycoprotein of Trypanosoma brucei is expressed transiently during development and can be regulated post-transcriptionally by glycerol or hypoxia. Genes Dev. 14:615-626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vickerman, K. 1985. Developmental cycles and biology of pathogenetic trypanosomes. Br. Med. Bull. 41:105-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vickerman, K. 1965. Polymorphism and mitochondrial activity in sleeping sickness trypanosomes. Nature 208:762-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitmarsh, A. J., and R. J. Davis. 2000. A central control for cell growth. Nature 403:255-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiese, M., Q. Wang, and I. Gorcke. 2003. Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase homologues from Leishmania mexicana. Int. J. Parasitol. 33:1577-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, S., and D. F. Klessig. 1997. Salicylic acid activates a 48-kDa MAP kinase in tobacco. Plant Cell 9:809-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziegelbauer, K., M. Quinten, H. Schwarz, T. W. Pearson, and P. Overath. 1990. Synchronous differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei from bloodstream to procyclic forms in vitro. Eur. J. Biochem. 192:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]