Abstract

Farnesyl diphosphate synthase is the most likely molecular target of aminobisphosphonates (e.g., risedronate), a set of compounds that have been shown to have antiprotozoal activity both in vitro and in vivo. This protein, together with other enzymes involved in isoprenoid biosynthesis, is an attractive drug target, yet little is known about the compartmentalization of the biosynthetic pathway. Here we show the intracellular localization of the enzyme in wild-type Leishmania major promastigote cells and in transfectants overexpressing farnesyl diphosphate synthase by using purified antibodies generated towards a homogenous recombinant Leishmania major farnesyl diphosphate synthase protein. Indirect immunofluorescence, together with immunoelectron microscopy, indicated that the enzyme is mainly located in the cytoplasm of both wild-type cells and transfectants. Digitonin titration experiments also confirmed this observation. Hence, while the initial step of isoprenoid biosynthesis catalyzed by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase is located in the mitochondrion, synthesis of farnesyl diphosphate by farnesyl diphosphate synthase is a cytosolic process. Leishmania major promastigote transfectants overexpressing farnesyl diphosphate synthase were highly resistant to risedronate, and the degree of resistance correlated with the increase in enzyme activity. Likewise, when resistance was induced by stepwise selection with the drug, the resulting resistant promastigotes exhibited increased levels of farnesyl diphosphate synthase. The overproduction of protein under different conditions of exposure to risedronate further supports the hypothesis that this enzyme is the main target of aminobisphosphonates in Leishmania cells.

Leishmaniasis is a group of diseases caused by a variety of Leishmania species. At least 20 different species can infect humans, originating cutaneous (oriental sore), mucocutaneous (espundia), and visceral (kala azar) leishmaniasis (14). The most lethal form is visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani, with untreated cases reaching ∼90% mortality within 6 to 24 months (3). This group of diseases affects more than 12 million people, with 2 million new cases worldwide per year (14). The classic treatment with pentavalent antimonials is unsatisfactory because of their toxicity, the difficulty in administration, and increasing resistance (11).

Aminobisphosphonates, pyrophosphate analogs which are in clinical use for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis, Paget's disease, hypercalcemia caused by malignancy, and tumor metastasis in bone since they are potent inhibitors of bone resorption (5, 42, 43, 45), were shown to inhibit the growth of amebas of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. It was found that the rankings of the aminobisphosphonate drugs in order of potency as inhibitors of Dictyostelium growth and as inhibitors of bone resorption are the same (46). This led to the proposition that the target of aminobisphosphonates in Dictyostelium amebas must be similar to the target in osteoclasts (6, 47). Indeed, as in osteoclasts (1, 25, 54) and plants (12), the intracellular target of aminobisphosphonates in D. discoideum is farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) (19).

A group of bisphosphonates was recently shown to be active against the proliferation of Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, Toxoplasma gondii, and Plasmodium falciparum in vitro (33). Moreover, risedronate effected the parasitological cure of visceral leishmaniasis (56) and pamidronate effected the parasitological cure of cutaneous leishmaniasis (44) in BALB/c mice. In addition, bisphosphonates have been shown to accumulate in tissues susceptible to infection by some of these parasites and to possess immunomodulatory effects (29) and very low toxicities, and since they are already FDA approved, they represent promising compounds for development as novel antiparasitic agents.

It has been postulated that the selective activity of aminobisphosphonates on trypanosomatids and apicomplexan parasites could result from their preferential accumulation due to the presence of a calcium- and pyrophosphate-rich organelle named the acidocalcisome (15, 53). This organelle would play the equivalent role of the bone mineral to which bisphosphonates are known to bind with high affinity (5, 42, 45); interestingly, D. discoideum has similar organelles, and it is possible that the accumulation of these drugs occurs through a similar mechanism (32, 47, 50). Moreover, interference of bisphosphonates with phosphate metabolism or other enzymes involved in intermediary metabolism in the Trypanosomatidae is plausible. Thus, several bisphosphonates have been identified that inhibit an exopolyphosphatase activity in Trypanosoma brucei and confer protection from death in a mouse model of T. brucei infection (26), and recently, a set of pyrophosphate analogues that inhibit the hexokinase activity of Trypanosoma cruzi have been described (23). FPPS and the mevalonate pathway have been studied in detail in eukaryotes. FPPS has been depicted as a cytosolic enzyme in animals and plants (24), based on results obtained from fractionation studies. Nevertheless, in the past decade, several reports revealed a predominantly peroxisomal FPPS localization in a variety of mammalian cells (38). The localization of the mevalonate pathway proteins in trypanosomatids has not been established fully. We previously described that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenyzme A (HMG-CoA) reductase is present in the mitochondria of Leishmania and Trypanosoma cruzi (40), while squalene synthase and Δ24,(25)-sterol methyltransferase were suggested to have a dual subcellular localization in glycosomes and mitochondrial/microsomal vesicles (52).

In the present study, we report the characterization of Leishmania major farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Overexpression of the enzyme renders cells proportionally resistant to bisphosphonates. We also show by means of permeabilization analysis, indirect immunofluorescence, and immunoelectron microscopy that the enzyme is cytosolic and that, consequently, isoprenoid biosynthesis is a multicompartmental process in Leishmania cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Protease inhibitor cocktail, geranyl diphosphate, and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) were purchased from Sigma. Fetal bovine serum and medium 199 were purchased from Gibco. [4-14C]IPP (57.5 mCi/mmol) was obtained from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences. The pET11c expression system was obtained from Novagen, and the pBK-CMV phagemid was obtained from Stratagene. Oligonucleotides LmFPPS1 (5′-CGCCGCGGT/CCAGCCC/GTGCTGG-3′), LmFPPS2 [5′-ATA/GTCG/CGTA/GCC(A/G/C)AC/TCTTA/GCC-3′], ATG-FPPS (5′-GGGAATTCCATATGGCGCACATGGAA-3′), TAA-FPPS (5′-CGCGGATCCTTACTTTTGGCGCTT-3′), LmFPPS3 (5′-GCGGATCCATGGCGCACATGGAA-3′), and LmFPPS4 (5′-GAAGATCTTTACTTTTGGCGCTT-3′) were synthesized at the Analytical Services of the López-Neyra Institute of Parasitology and Biomedicine.

Culture methods.

Promastigote forms derived from Leishmania major strain 252 were grown in M199 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). Leishmania major 252 promastigotes resistant to 1,200 μM risedronate were selected in a stepwise manner, beginning at 150 μM risedronate and progressing through several passages to 300, 600, and 1,200 μM.

Cloning of the L. major FPPS gene and DNA sequencing.

A fragment of the L. major FPPS gene was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide primers LmFPPS1 and LmFPPS2. The amino acid sequences of different FPPSs were used to design degenerate oligonucleotides targeting two highly conserved regions. PCR was performed by using genomic DNA as a template. The resulting fragment was labeled with 32P for screening of an L. major λ-Zap library (8). Phage (105) were analyzed, and one positive clone was chosen for excision. Plasmid DNA from these cells was isolated and cleaved with EcoRI and XhoI to liberate an insert of 2,000 bp.

Plasmid constructs and transfections.

The coding sequence of the FPPS gene from L. major was amplified by using the 5′ LmFPPS3 and 3′ LmFPPS4 primers, which contain flanking BamHI and BglII sites, respectively. The resulting fragment was cloned into pX63NEO (30), and the construct was verified by sequencing. Transfectants were selected using neomycin (16 μg/ml).

Northern and Southern blot analyses.

Total RNAs from wild-type and resistant cells were isolated by using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and were used for Northern blotting by standard methodology. The membrane was hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled L. major FPPS probe. For normalization, an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled L. major dUTPase (Leishmania major coding sequence for dUTPase) probe was used. Southern blot analyses of genomic DNA digested with HindIII, PstI, and NcoI were performed by using an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled L. major FPPS probe for analysis of gene amplification.

Expression and purification of L. major FPPS from Escherichia coli.

Two oligonucleotide primers based on the 5′ and 3′ coding regions of the L. major FPPS gene were used to amplify the entire coding sequence. The PCR product was first cloned into pET11c to give pETLmFPPS, which was used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Bacterial clones were grown in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Induction was performed for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in sonication buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol [vol/vol], and protease inhibitor cocktail containing leupeptin [0.02 mg/ml], benzamidine [1 mM], trypsin inhibitor [0.05 mg/ml], phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [52 μM], aprotinin [0.05 mg/ml], and phenanthroline [0.01 M]), disrupted by sonication, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was collected, and saturated (NH4)2SO4 was added to 40% saturation. The solution was stirred for 20 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min. The resulting pellet was dissolved in 4 ml of sonication buffer and diluted with start buffer (12 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. The protein solution was applied to a column of hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) previously equilibrated with start buffer. The column was washed with buffer at a rate of 0.4 ml/min and was developed with a linear gradient of 12 to 60 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Fractions containing enzyme activity were pooled and concentrated on an Amicon concentrator (Centriprep column; Millipore). The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (4), with bovine serum albumin as a standard, and analyzed for purity by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Enzyme activity assays.

The activity of the enzyme was determined by radiometric assay with a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 850 nmol of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 85 nmol of MgCl2, 10 nmol of geranyl diphosphate, and 5 nmol of isopentenyl diphosphate with a specific activity of 6.34 Ci/mol for [4-14C] isopentenyl diphosphate. The enzyme reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 ng of purified recombinant protein, incubated for 15 min at 30°C, and terminated by the addition of 1 ml of a saturated NaCl solution. The reaction product was quantified as previously described (48). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the activity required to incorporate 1 nmol of [4-14C]IPP into [4-14C]FPP per minute.

Western blotting and generation of antibodies against L. major FPPS.

To obtain an anti-FPPS antibody, purified LmFPPS protein was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and mixed with Freund's adjuvant before injection into a rabbit. Four inoculations of 400 μg of protein were carried out before obtaining the anti-FPPS serum, at a titer of 1:1,000,000. The antiserum was subjected to affinity purification using a resin prepared by incubating the same protein used for immunization with an activated Affi-gel 15 immunoaffinity support (Bio-Rad). Total Leishmania proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12.5%) and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with a 1:400,000 dilution of a rabbit anti-FPPS polyclonal antiserum against pure recombinant L. major farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Bound antibodies were revealed by using goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G at a dilution of 1:5,000 (Promega) and an ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Densitometric analyses of Western blots were performed by using the 1D-manager program.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Logarithmic-phase L. major cells were washed twice with 1× PBS, pH 7.2, and resuspended in the same solution containing 100 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Molecular Probes). Cells were then spotted on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40 (Sigma) for 5 min, and then labeled with purified rabbit polyclonal anti-LmFPPS antibody diluted 1:1,200 in blocking buffer for wild-type cells and 1:20,000 for cells overexpressing FPPS. Slides were mounted with Vectashield and DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole). In colocalization studies with anti-aldolase (anti-ALD), an antibody directed towards the glycosomal aldolase of Trypanosoma brucei (20), the dilution used was 1:1,200, while anti-LmFPPS was labeled directly with Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes) and used at a 1:1,200 dilution.

Immunogold staining.

Logarithmic-phase L. major cells were fixed for 12 h at 4°C in 0.4% grade I glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde, 3.5% sucrose, and 0.5% picric acid in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Gold labeling was performed as previously described (40). Sections were counterstained with 2% uranyl acetate (EMS) and observed and photographed in a Zeiss 902 electron microscope.

Digitonin titration.

Parasites were grown to 1.5 × 107 and collected by centrifugation, and digitonin titration was performed as previously described (40). The supernatants were used to assay the enzymatic activities of pyruvate kinase (cytosolic enzyme) (7), hexokinase (glycosomal enzyme) (41), and citrate synthase (mitochondrial enzyme) (34).

RESULTS

Characterization of recombinant LmFPPS.

At the time we started this work, the sequence of the LmFPPS gene was not present in databases. Therefore, isolation was performed using degenerate oligonucleotides. The amino acid sequences of FPPSs from several organisms were used to design primers LmFPPS1 and LmFPPS2, corresponding to two highly conserved regions in FPPSs. A fragment of 483 bp was PCR amplified from L. major genomic DNA, sequenced, and found to encode a peptide highly similar to FPPSs from other organisms. The whole LmFPPS gene open reading frame of 1,086 bp (the splice leader was located 168 bp upstream of ATG) was obtained by screening a cDNA library using the PCR fragment as a probe (see Materials and Methods). It encodes a peptide of 362 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 40.9 kDa and is identical to the FPPS coding sequence available at present in the EMBL database (accession number CAJ04700). The LmFPPS protein presents the seven conserved regions typical of prenyltransferases (28), which are located in the immediate vicinity of the deep cleft (51) with the two aspartate-rich motifs; the first, a DDXXD or DDXXXXD sequence corresponding to region II, binds the pyrophosphate residue in the allylic substrates, while the second, a DDXXD motif corresponding to region VI, binds IPP. Similar to the case for other trypanosomatids (35, 36), LmFPPS has an insertion of 11 amino acids at position 174 near the active site which is absent in human FPPS (55). A recent study reporting the crystallization and X-ray diffraction study of the farnesyl diphosphate synthase from Trypanosoma cruzi, which also contains the additional amino acids (17), showed that this insertion folds as a tight loop, with a reverse turn at Pro182. A BLAST search of the protein database illustrated that the amino acid sequence from L. major has 36 to 45% identity and 46 to 53% similarity with other representative (mammalian, plant, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) FPPSs.

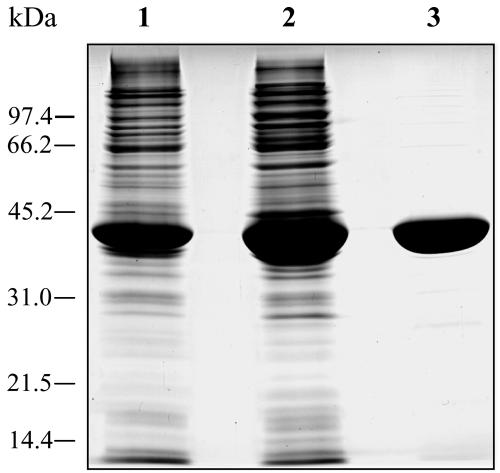

The purified recombinant LmFPPS protein exhibited 3.3 times more activity than crude extracts of Escherichia coli transformed with the expression plasmid pETLmFPPS, where expression of FPPS is under the control of the T7 promoter. The protein was produced without tags, and the yield of the purification procedure was 25% (Table 1) and involved two steps: precipitation with 40% saturated (NH4)2SO4 and hydroxyapatite chromatography. Enzyme purity was judged by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1). The protein obtained this way was stable at 4°C for several weeks and was used for polyclonal antibody production (see Materials and Methods). Standard procedures were used to determine kinetic parameters. Km and Vmax values were obtained by a nonlinear regression fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The Km values for geranyl diphosphate and IPP were 13.77 ± 0.3 and 30.57 ± 0.5 μM, respectively, while the Vmax was 3,225 ± 12 units/mg.

TABLE 1.

Purification of L. major FPPS

| Purification step | Volume (ml) | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg) | Total activity (U) | Purification (fold) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude supernatant | 49 | 445.9 | 529.3 | 235.997 | 1 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation | 4 | 165.4 | 1,059.3 | 175.201 | 2 | 74 |

| Hydroxyapatite chromatography | 6.6 | 34.5 | 1,757.6 | 60.672 | 3.32 | 25 |

FIG. 1.

LmFPPS purification. Lane 1, crude extract (21 μg protein); lane 2, 0 to 40% saturated (NH4)2SO4 fraction (21 μg of protein); lane 3, protein from hydroxyapatite chromatography (21 μg of protein).

Overexpression of LmFPPS confers resistance to risedronate.

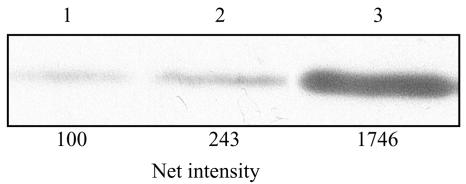

The role of FPPS in the primary response to risedronate was analyzed in parasites overexpressing FPPS. Overexpressing promastigotes were obtained by transfection of wild-type L. major 252 with pX63NEO-FPPS, and levels of enzyme were estimated by Western blotting and activity determinations. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the drug was determined with pX63NEO-FPPS-transformed L. major promastigotes and wild-type cells. The IC50 for overexpressing parasites was 9,121 ± 54 μM, 70-fold higher than that for wild-type cells. Western blotting showed that FPPS was strongly overproduced in transfectants with respect to wild-type cells (Fig. 2), and this increase was estimated to be approximately 17-fold by densitometric analysis. Activity measurements in extracts of wild-type and FPPS-overexpressing parasites were performed. The specific activity in overexpressing mutants was 280 nmol/min/mg protein versus 3.96 nmol/min/mg protein in wild-type cells, again 70-fold higher and of the same order of magnitude as the IC50 for risedronate.

FIG. 2.

Determination of LmFPPS expression by Western blot analysis of wild-type and transfectant cells. Lane 1, wild-type promastigotes; lane 2, pX63NEO control parasites; lane 3, pX63NEO-FPPS parasites overexpressing FPPS protein. The membrane was incubated with a rabbit anti-LmFPPS polyclonal antibody. Nine micrograms of protein was loaded into each lane. The net intensities of the individual LmFPPS bands were determined with 1D-manager analysis software.

Stepwise selection for resistance to risedronate renders cells that exhibit increased levels of FPPS.

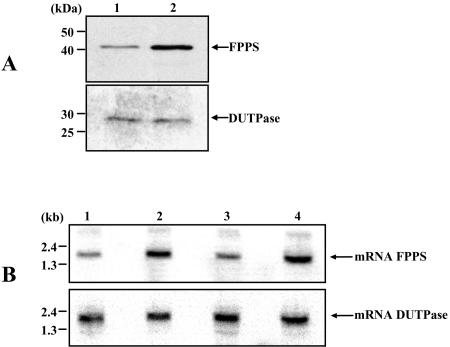

Leishmania major 252 promastigotes resistant to 1,200 μM risedronate (10-fold increase relative to wild-type cells) were generated by exposure to increasing concentrations of the drug. In the adaptive process, the criterion for increasing the drug concentration was that the generation time of parasites in the presence of risedronate was the same as that of wild-type cells. Resistant cells had significantly (fourfold) increased levels of FPPS (Fig. 3A). Likewise, Northern blot analysis showed that mRNA levels were equally enhanced (Fig. 3B). Consequently, as a result of drug pressure, cells overcame the effects of risedronate by overexpressing the target protein. No mutations took place during the selection of resistance, as evidenced by the isolation and sequencing of FPPS from resistant cells. In addition, Southern blot hybridization under conditions that allow for the detection of gene amplification showed that the overproduction of enzyme was not due to LmFPPS gene amplification (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of FPPS levels in wild-type and risedronate-resistant cells. (A) Western blotting was performed with extracts prepared from 106 wild-type cells (lane 1) and 106 resistant cells (lane 2). The membrane was incubated with a rabbit anti-LmFPPS polyclonal antibody. The blot was normalized with an anti-LmdUTPase polyclonal antibody. (B) Northern blotting was performed with 5 and 10 μg of total RNA from wild-type (lanes 1 and 3) and resistant (lanes 2 and 4) parasites. The blot was hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled LmFPPS probe and normalized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled LmdUTPase probe.

Intracellular localization of FPPS.

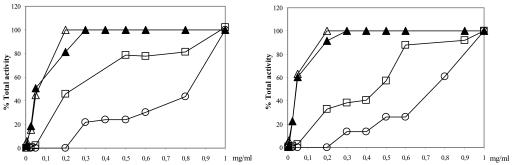

We sought to determine the location of FPPS in Leishmania major promastigotes. This enzyme was first believed to be localized in the cytosol of plants (24) and animals but later was described as mitochondrial (13) and plastidic (49). Moreover, it has been described that peroxisomes are the major site of the synthesis of FPPS from mevalonate in human cells (2), while other studies maintain a cytosolic location for the conversion of mevalonic acid to isopentenyl diphosphate (21, 22). Digitonin permeabilization is a classical way to assess the subcellular localization of a protein. The plasma membrane is permeabilized with low doses of detergent, whereas glycosomal and mitochondrial membranes are permeabilized at higher concentrations. When studies were performed with both wild-type and FPPS-overexpressing parasites, we observed that FPPS activity was present in the supernatant and was released in a pattern that closely resembles that of the cytosolic enzyme pyruvate kinase (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Digitonin titration of LmFPPS. Activities of pyruvate kinase (open triangles), hexokinase (open squares), citrate synthase (open circles), and farnesyl diphosphate synthase (closed triangles) were assayed in supernatants of whole L. major suspensions in solutions with increasing digitonin concentrations. Total enzyme activity is expressed as a percentage, taking as 100% the total activity obtained in supernatants after permeabilization with 1 mg/ml of digitonin. (Left) Activities recovered from L. major wild-type supernatants; (right) activities recovered from supernatants of L. major parasites transfected with pX63NEO-LmFPPS and overexpressing FPPS.

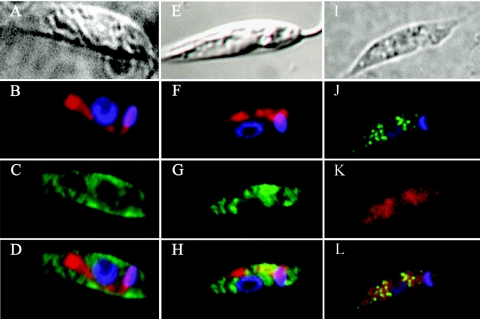

The location of FPPS in Leishmania was further analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence using purified antibodies, as described in Materials and Methods. The analysis was performed with both wild-type and transfected cells that were permeabilized with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and incubated with the rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-LmFPPS and an anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (green). Cells were also labeled simultaneously with MitoTracker (red) for mitochondrion visualization and with DAPI, which stains both nuclear and mitochondrial kinetoplast DNA. As shown in panels A, B, C, and D of Fig. 5, green fluorescence was clearly associated with the cytosol of cells, and no particular concentration of the dye appeared to be specifically related to glycosomes or mitochondria. In the case of overexpressing promastigotes (panels E, F, G, and H), a higher antibody dilution was required for efficient visualization of FPPS, and cells exhibited the same staining pattern as wild-type cells. Colocalization studies using an antibody directed towards the glycosomal enzyme aldolase (panels I, J, K, and L) clearly evidenced that the pattern for FPPS resembles that of a cytosolic enzyme.

FIG. 5.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. (A, B, C, D, I, J, K, and L) Wild-type cells; (E, F, G, and H) FPPS-overexpressing cells. (A, E, and I) Phase-contrast images; (B and F) DAPI and Mitotracker staining, indicating the localization of DNA in the nucleus and kinetoplast in blue and the mitochondrion in red, respectively; (C and G) FITC staining (green) using the LmFPPS antibody diluted 1:1,200 for wild-type cells and 1:20,000 for transfected cells; (D and H) overlays of FITC, MitoTracker, and DAPI staining; (J) FITC staining (green) using the anti-ALD antibody diluted 1:1,200 and DAPI; (K) staining with the LmFPPS antibody labeled directly with Alexa Fluor 594 (red); (L) overlay of FITC (anti-ALD), Alexa Fluor 594 (anti-LmFPPS), and DAPI staining.

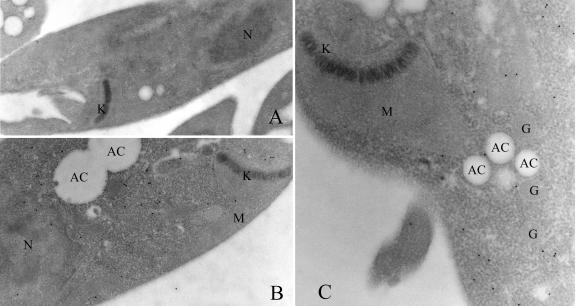

Finally, analysis of the intracellular milieu of farnesyl diphosphate synthase was performed by electron microscopy. Wild-type cells as well as overexpressing transfected cells were fixed and embedded in LRWhite resin and incubated with a purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the homogeneous purified recombinant protein. Photographs of thin sections demonstrated that most of the gold-labeled particles were localized in the cytoplasm, both in control (Fig. 6A) and in FPPS-overexpressing (Fig. 6B and C) cells, while practically no labeling was associated with structures such as the mitochondria or glycosomes. Counting of gold grains in an average of 10 cells evidenced that approximately 83% of the label was found in the cytosol, while 6% was found in the nucleus, 6% was in the mitochondria, and <3% was in the glycosomes. Similar observations were obtained for overexpressing transfectants, where 92% of the gold particles were present in the cytosolic compartment. Taken together, all of these results strongly suggest that FPPS is mainly a cytosolic enzyme in Leishmania promastigotes.

FIG. 6.

Immunoelectron microscopy localization of FPPS in control cells and transfectant cells overexpressing the enzyme. Leishmania major promastigotes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.4% glutaraldehyde and embedded in LRWhite resin. Thin sections were immunolabeled with purified anti-LmFPPS (diluted 1:3,000 for transfectant cells and 1:1,000 for wild-type control cells) polyclonal antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to gold (10 nm). Most of the gold-labeled particles were localized in the cytosol in wild-type cells (A) as well as in overexpressing FPPS transfectant cells (B and C). Magnification: ×16,000 for panel A, ×25,000 for panel B, and ×40,000 for panel C. N, nucleus; M, mitochondrion; G, glycosome; K, kinetoplast; AC, acidocalcisome.

DISCUSSION

Leishmania spp. are a diverse group of intracellular pathogens that cause considerable mortality and morbidity worldwide, and hence the development of novel chemotherapeutic approaches is of importance, since current therapy is unsatisfactory because of significant toxicity, the development of resistance, and the high cost (11). The sterol pathway, and in particular, farnesyl diphosphate synthase is a promising candidate target for the development of new antiprotozoal drugs. FPP is used by trypanosomatids in the biosynthesis of dolichol and sterols, such as ergosterol, and in protein prenylation (57); accordingly, FPPS appears to be essential for parasite survival, since recent studies have demonstrated the essentiality of FPPS in T. brucei by means of RNA interference (36).

Recently, a clear correlation was found between the abilities that bisphosphonates have to inhibit human FPPS in vitro, to reduce protein prenylation in osteoclasts in vitro, and to slow down bone resorption in vivo (16). Likewise, a series of studies have demonstrated that bisphosphonates have significant activity against the proliferation of T. cruzi, T. brucei, L. donovani, T. gondii, and P. falciparum (33). We now provide evidence that further supports the hypothesis that FPPS is the primary target of aminobisphosphonates in Leishmania cells and that forced FPPS overexpression leads to risedronate resistance. We further show that when a population of cells is placed under risedronate selection, overproduction of FPPS confers drug resistance. Taken together, these observations sustain gene overexpression as a method for target validation which has a major benefit over other methods of drug target identification in that, as a genetic approach, it is unbiased and is based on the ability of a promastigote to overcome the toxic effect of the drug when the individual gene is overexpressed.

Similar observations regarding the mode of action of risedronate have been documented for osteoclasts (16), Toxoplasma gondii (31), and Dictyostelium discoideum. In the last case, strains of amebas were selected for having partial resistance to the growth-inhibitory effects of alendronate or risedronate, and the resulting mutant strains appeared to overproduce FPPS (19), thus indicating that the intracellular target for the antiresorptive aminobisphosphonate drugs in Dictyostelium discoideum was the enzyme farnesyl diphosphate synthase.

The intracellular localization of isoprenoid biosynthesis in the Trypanosomatidae is subject to controversy. Biochemical fractionation studies have reported a glycosomal location for HMG-CoA reductase (10), while more recent immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy studies have shown that this enzyme is located in the mitochondria of both Leishmania major and Trypanosoma cruzi (40). Other enzymes of the metabolic pathway, such as SQS and Δ24,(25)-sterol methyltransferase, have a dual location in the mitochondrion and glycosome, as also determined by biochemical analysis of subcellular fractions obtained by gradient centrifugation (52). Little is known for trypanosomatids about the localization of other proteins of the mevalonate pathway. The description of HMG-CoA reductase as a mitochondrial enzyme (40) has interest in relation to studies performed with Leishmania that established leucine as a major substrate for the generation of sterols (18). The latter would occur through degradation of the amino acid to HMG-CoA, a process that has been described to be mitochondrial in different cell types, although this issue remains to be established for the Trypanosomatidae. Leucine could represent a main carbon source for isoprenoid biosynthesis, contributing to the metabolic economy in these cells, as occurs in animal tissues, plants, and fungi.

Biochemical studies (10, 52) and the predicted glycosomal proteome (39) have depicted certain enzymes of the isoprenoid pathway to be glycosomal, and an analysis of the FPPS amino acid sequence of Leishmania predicts a peroxisomal targeting signal (PTS)-2 targeting signal at position 179 (KLDAKVAHA) (9), yet this is well beyond the expected site for a typical PTS-2 (in the first 20 amino acids of the N terminus). In addition, there is no clearly identifiable PTS-1. Moreover, predictions with PSORT (37) indicate a preferentially cytosolic location. Indeed, we now show that FPPS is mainly found in the cytosol of L. major and does not colocalize with the glycosomal protein aldolase. FPP is an important substrate for a number of critical branch-point enzymes, including those involved in biosynthesis of squalene, sterols, farnesylated and geranylated proteins, dolichols, coenzyme Q, and the isoprenoid moiety of heme A. Interestingly, the product of the FPPS reaction can be used by other enzymes that have been shown to be cytosolic, such as prenyltransferases (58). Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that since HMG-CoA reductase is a mitochondrial enzyme, either mevalonate or the phosphorylated products of mevalonate would have to cross the mitochondrial membrane to serve as substrates for FPP synthesis. This process has not been described previously for protozoa and may be transporter mediated. Studies aimed at establishing the location in Leishmania of steps prior to FPPS are in progress in order to understand how trafficking of intermediates may occur.

In summary, we have determined by using a variety of methods that FPPS is mainly located in the cytosol of Leishmania cells and therefore that isoprenoid biosynthesis exhibits particular characteristics in the Trypanosomatidae regarding its intracellular location, since the steps involved take place in multiple subcellular compartments different from those observed in mammalian cells (27). How the intermediates travel between different intracellular compartments and the possible metabolic significance of the existence of multiple sites are currently under study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the European Commission INCO-DEV (ICA4-2000-100028), the Spanish Plan Nacional de Investigación (SAF2004-03828), and the Plan Andaluz de Investigación (CVI199). A.O.G. is a fellow of the Spanish PFPU of the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

We thank Eric Oldfield (University of Illinois) for providing risedronate and Paul Michels for the antibody to Trypanosoma brucei aldolase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergstrom, J. D., R. G. Bostedor, P. J. Masarachia, A. A. Reszka, and G. Rodan. 2000. Alendronate is a specific, nanomolar inhibitor of farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 373:231-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biardi, L., and S. K. Krisans. 1996. Compartmentalization of cholesterol biosynthesis. Conversion of mevalonate to farnesyl diphosphate occurs in the peroxisomes. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1784-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bora, D. 1999. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in India. Natl. Med. J. India 12:62-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, D. L., and R. Robbins. 1999. Developments in the therapeutic applications of bisphosphonates. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 39:651-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, R. J., E. van Beek, D. J. Watts, C. W. Lowik, and S. E. Papapoulos. 1998. Differential effects of aminosubstituted analogs of hydroxy bisphosphonates on the growth of Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Bone Miner. Res. 13:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callens, M., D. A. Kuntz, and F. R. Opperdoes. 1991. Characterization of pyruvate kinase of Trypanosoma brucei and its role in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 47:19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho, A., R. Arrebola, J. Pena-Diaz, L. M. Ruiz-Perez, and D. Gonzalez-Pacanowska. 1997. Description of a novel eukaryotic deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase in Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 325:441-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chudzik, D. M., P. A. Michels, S. de Walque, and W. G. Hol. 2000. Structures of type 2 peroxisomal targeting signals in two trypanosomatid aldolases. J. Mol. Biol. 300:697-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Concepcion, J. L., D. Gonzalez-Pacanowska, and J. A. Urbina. 1998. 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase in Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: subcellular localization and kinetic properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 352:114-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croft, S. L., and G. H. Coombs. 2003. Leishmaniasis—current chemotherapy and recent advances in the search for novel drugs. Trends Parasitol. 19:502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cromartie, T. H., K. J. Fisher, and J. N. Grossman. 1999. The discovery of a novel site of action for herbicidal bisphosphonates. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 63:114-126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunillera, N., A. Boronat, and A. Ferrer. 1997. The Arabidopsis thaliana FPS1 gene generates a novel mRNA that encodes a mitochondrial farnesyl-diphosphate synthase isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15381-15388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desjeux, P. 2004. Leishmaniasis: current situation and new perspectives. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:305-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Docampo, R., and S. N. Moreno. 1999. Acidocalcisome: a novel Ca2+ storage compartment in trypanosomatids and apicomplexan parasites. Parasitol. Today 15:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunford, J. E., K. Thompson, F. P. Coxon, S. P. Luckman, F. M. Hahn, C. D. Poulter, F. H. Ebetino, and M. J. Rogers. 2001. Structure-activity relationships for inhibition of farnesyl diphosphate synthase in vitro and inhibition of bone resorption in vivo by nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 296:235-242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabelli, S. B., J. S. McLellan, A. Montalvetti, E. Oldfield, R. Docampo, and L. M. Amzel. 2006. Structure and mechanism of the farnesyl diphosphate synthase from Trypanosoma cruzi: implications for drug design. Proteins 62:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginger, M. L., M. L. Chance, I. H. Sadler, and L. J. Goad. 2001. The biosynthetic incorporation of the intact leucine skeleton into sterol by the trypanosomatid Leishmania mexicana. J. Biol. Chem. 276:11674-11682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grove, J. E., R. J. Brown, and D. J. Watts. 2000. The intracellular target for the antiresorptive aminobisphosphonate drugs in Dictyostelium discoideum is the enzyme farnesyl diphosphate synthase. J. Bone Miner. Res. 15:971-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerra-Giraldez, C., L. Quijada, and C. E. Clayton. 2002. Compartmentation of enzymes in a microbody, the glycosome, is essential in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell Sci. 115:2651-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogenboom, S., J. J. Tuyp, M. Espeel, J. Koster, R. J. Wanders, and H. R. Waterham. 2004. Mevalonate kinase is a cytosolic enzyme in humans. J. Cell Sci. 117:631-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogenboom, S., J. J. Tuyp, M. Espeel, J. Koster, R. J. Wanders, and H. R. Waterham. 2004. Phosphomevalonate kinase is a cytosolic protein in humans. J. Lipid Res. 45:697-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudock, M. P., C. E. Sanz-Rodriguez, Y. Song, J. M. Chan, Y. Zhang, S. Odeh, T. Kosztowski, A. Leon-Rossell, J. L. Concepcion, V. Yardley, S. L. Croft, J. A. Urbina, and E. Oldfield. 2006. Inhibition of Trypanosoma cruzi hexokinase by bisphosphonates. J. Med. Chem. 49:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugueney, P., F. Bouvier, A. Badillo, J. Quennemet, A. d'Harlingue, and B. Camara. 1996. Developmental and stress regulation of gene expression for plastid and cytosolic isoprenoid pathways in pepper fruits. Plant Physiol. 111:619-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller, R. K., and S. J. Fliesler. 1999. Mechanism of aminobisphosphonate action: characterization of alendronate inhibition of the isoprenoid pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266:560-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotsikorou, E., Y. Song, J. M. Chan, S. Faelens, Z. Tovian, E. Broderick, N. Bakalara, R. Docampo, and E. Oldfield. 2005. Bisphosphonate inhibition of the exopolyphosphatase activity of the Trypanosoma brucei soluble vacuolar pyrophosphatase. J. Med. Chem. 48:6128-6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs, W. J., and S. Krisans. 2003. Cholesterol biosynthesis and regulation: role of peroxisomes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 544:315-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koyama, T. 1999. Molecular analysis of prenyl chain elongating enzymes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:1671-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunzmann, V., E. Bauer, J. Feurle, F. Weissinger, H. P. Tony, and M. Wilhelm. 2000. Stimulation of gammadelta T cells by aminobisphosphonates and induction of antiplasma cell activity in multiple myeloma. Blood 96:384-392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBowitz, J. H., C. M. Coburn, D. McMahon-Pratt, and S. M. Beverley. 1990. Development of a stable Leishmania expression vector and application to the study of parasite surface antigen genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:9736-9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling, Y., G. Sahota, S. Odeh, J. M. Chan, F. G. Araujo, S. N. Moreno, and E. Oldfield. 2005. Bisphosphonate inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondii growth: in vitro, QSAR, and in vivo investigations. J. Med. Chem. 48:3130-3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchesini, N., F. A. Ruiz, M. Vieira, and R. Docampo. 2002. Acidocalcisomes are functionally linked to the contractile vacuole of Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8146-8153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin, M. B., J. S. Grimley, J. C. Lewis, H. T. Heath III, B. N. Bailey, H. Kendrick, V. Yardley, A. Caldera, R. Lira, J. A. Urbina, S. N. Moreno, R. Docampo, S. L. Croft, and E. Oldfield. 2001. Bisphosphonates inhibit the growth of Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, Toxoplasma gondii, and Plasmodium falciparum: a potential route to chemotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 44:909-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massarini, E., and J. J. Cazzulo. 1975. Two forms of citrate synthase in a marine pseudomonad. FEBS Lett. 57:134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montalvetti, A., B. N. Bailey, M. B. Martin, G. W. Severin, E. Oldfield, and R. Docampo. 2001. Bisphosphonates are potent inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:33930-33937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montalvetti, A., A. Fernandez, J. M. Sanders, S. Ghosh, E. Van Brussel, E. Oldfield, and R. Docampo. 2003. Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase is an essential enzyme in Trypanosoma brucei. In vitro RNA interference and in vivo inhibition studies. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17075-17083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakai, K., and P. Horton. 1999. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:34-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olivier, L. M., W. Kovacs, K. Masuda, G. A. Keller, and S. K. Krisans. 2000. Identification of peroxisomal targeting signals in cholesterol biosynthetic enzymes. AA-CoA thiolase, hmg-coa synthase, MPPD, and FPP synthase. J. Lipid Res. 41:1921-1935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opperdoes, F. R., and J. P. Szikora. 2006. In silico prediction of the glycosomal enzymes of Leishmania major and trypanosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 147:193-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pena-Diaz, J., A. Montalvetti, C. L. Flores, A. Constan, R. Hurtado-Guerrero, W. De Souza, C. Gancedo, L. M. Ruiz-Perez, and D. Gonzalez-Pacanowska. 2004. Mitochondrial localization of the mevalonate pathway enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase in the Trypanosomatidae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1356-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Racagni, G. E., and E. E. Machado de Domenech. 1983. Characterization of Trypanosoma cruzi hexokinase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 9:181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodan, G. A. 1998. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 38:375-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodan, G. A., and T. J. Martin. 2000. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science 289:1508-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez, N., B. N. Bailey, M. B. Martin, E. Oldfield, J. A. Urbina, and R. Docampo. 2002. Radical cure of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis by the bisphosphonate pamidronate. J. Infect. Dis. 186:138-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers, M. J., D. J. Watts, and R. G. Russell. 1997. Overview of bisphosphonates. Cancer 80:1652-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers, M. J., D. J. Watts, R. G. Russell, X. Ji, X. Xiong, G. M. Blackburn, A. V. Bayless, and F. H. Ebetino. 1994. Inhibitory effects of bisphosphonates on growth of amoebae of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9:1029-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers, M. J., X. Xiong, R. J. Brown, D. J. Watts, R. G. Russell, A. V. Bayless, and F. H. Ebetino. 1995. Structure-activity relationships of new heterocycle-containing bisphosphonates as inhibitors of bone resorption and as inhibitors of growth of Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae. Mol. Pharmacol. 47:398-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanders, J. M., A. O. Gomez, J. Mao, G. A. Meints, E. M. Van Brussel, A. Burzynska, P. Kafarski, D. Gonzalez-Pacanowska, and E. Oldfield. 2003. 3-D QSAR investigations of the inhibition of Leishmania major farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase by bisphosphonates. J. Med. Chem. 46:5171-5183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanmiya, K., O. Ueno, M. Matsuoka, and N. Yamamoto. 1999. Localization of farnesyl diphosphate synthase in chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 40:348-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlatterer, C., S. Buravkov, K. Zierold, and G. Knoll. 1994. Calcium-sequestering organelles of Dictyostelium discoideum: changes in element content during early development as measured by electron probe X-ray microanalysis. Cell Calcium 16:101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarshis, L. C., M. Yan, C. D. Poulter, and J. C. Sacchettini. 1994. Crystal structure of recombinant farnesyl diphosphate synthase at 2.6-A resolution. Biochemistry 33:10871-10877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Urbina, J. A., J. L. Concepcion, S. Rangel, G. Visbal, and R. Lira. 2002. Squalene synthase as a chemotherapeutic target in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 125:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urbina, J. A., B. Moreno, S. Vierkotter, E. Oldfield, G. Payares, C. Sanoja, B. N. Bailey, W. Yan, D. A. Scott, S. N. Moreno, and R. Docampo. 1999. Trypanosoma cruzi contains major pyrophosphate stores, and its growth in vitro and in vivo is blocked by pyrophosphate analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33609-33615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Beek, E., E. Pieterman, L. Cohen, C. Lowik, and S. Papapoulos. 1999. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates inhibit isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase/farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase activity with relative potencies corresponding to their antiresorptive potencies in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 255:491-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkin, D. J., S. Y. Kutsunai, and P. A. Edwards. 1990. Isolation and sequence of the human farnesyl pyrophosphate synthetase cDNA. Coordinate regulation of the mRNAs for farnesyl pyrophosphate synthetase, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase by phorbol ester. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4607-4614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yardley, V., A. A. Khan, M. B. Martin, T. R. Slifer, F. G. Araujo, S. N. Moreno, R. Docampo, S. L. Croft, and E. Oldfield. 2002. In vivo activities of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase inhibitors against Leishmania donovani and Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:929-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yokoyama, K., P. Trobridge, F. S. Buckner, J. Scholten, K. D. Stuart, W. C. Van Voorhis, and M. H. Gelb. 1998. The effects of protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors on trypanosomatids: inhibition of protein farnesylation and cell growth. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 94:87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yokoyama, K., P. Trobridge, F. S. Buckner, W. C. Van Voorhis, K. D. Stuart, and M. H. Gelb. 1998. Protein farnesyltransferase from Trypanosoma brucei. A heterodimer of 61- and 65-kDa subunits as a new target for antiparasite therapeutics. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26497-26505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]