Abstract

GroESL-overproducing Lactobacillus paracasei NFBC 338 was dried, and its viability was compared with that of controls. Spray- and freeze-dried cultures overproducing GroESL exhibited ∼10-fold and 2-fold better survival, respectively, demonstrating the importance of GroESL in stress tolerance, which can be exploited to enhance the technological performance of sensitive probiotic cultures.

The health benefits associated with consumption of probiotic bacteria have been well characterized (13, 18). From a processing perspective, these microorganisms must be suitable for large-scale industrial production, so that up to 107 CFU g−1 are present in a food product at the end of its shelf-life. Spray-drying is an effective method for producing stable powders at low operating costs; however, the survival rates of lactic acid bacteria are often low (12), and the loss of viability is caused principally by cell membrane damage (1). Freeze-drying exposes cells to attenuating effects of freezing and rehydration. In addition, the secondary structures of RNA and DNA stabilize, resulting in reduced efficacy of DNA replication, transcription, and translation (27).

Lactobacillus paracasei NFBC 338 is a suitable probiotic candidate for spray-drying (8), and heat or salt adaptation increased its tolerance to spray drying (6). As GroESL was upregulated following heat stress of L. paracasei NFBC 338, we homologously overexpressed the GroESL operon in L. paracasei NFBC 338, thereby conferring protection during heat, salt, and butanol stresses (5). The chaperone protein GroESL refolds denatured proteins during heat stress (17). The functions of the chaperone do not appear to be limited to heat stress but involve a wider role in cellular processes, such as growth (7), mRNA stability (9), and cytoplasmic protein folding (10). The studies described in this paper built on these findings and demonstrated that L. paracasei NFBC 338 overproducing GroESL exhibited enhanced survival during drying, thus demonstrating a novel use for an overproduced chaperone protein.

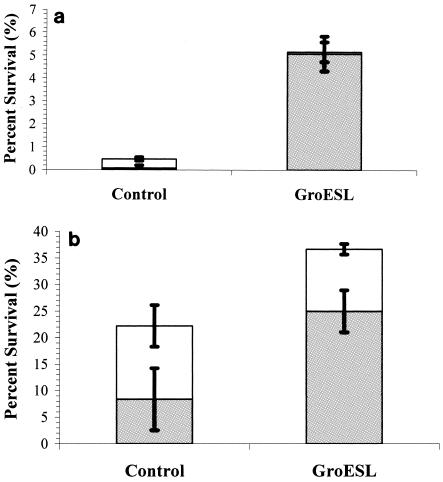

In order to evaluate the significance of overexpression of GroESL on the technological performance of a probiotic strain during drying, L. paracasei NFBC 338 containing either pGRO2 (an overproducer of GroESL) or pMSP3535 (control) was grown to the late exponential phase as previously described (5), centrifuged, suspended in reconstituted skim milk (RSM) (20%, wt/vol) to a final density of 2.0 × 109 to 2.5 × 109 CFU g−1, and spray-dried. A laboratory-scale spray-dryer (model B191 Buchi mini spray-dryer; Flawil, Switzerland) was used to process samples at a constant air inlet temperature of 180°C and an outlet temperature of 95 to 100°C, and the percentage of surviving bacteria was determined as described previously (8). Following spray-drying, cultures overproducing GroESL exhibited approximately 10-fold better survival (P < 0.05) than controls; this treatment resulted in powders that contained 8.03 × 107 CFU g−1 and exhibited 5.15% survival, while cultures of L. paracasei NFBC 338 transformed with plasmid pMSP3535 (control) exhibited only 0.46% survival and contained 1.12 × 107 CFU g−1 (Fig. 1a). In a recent study, overexpression of BetL in Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118 using a nisin-inducible promoter increased the survival after spray-drying up to fivefold (19). Previously, we found that up to 16- to 18-fold better survival of L. paracasei NFBC 338 spray-dried in RSM (20%, wt/vol) occurred at outlet temperature 95 to 105°C as a result of salt or heat adaptation (6), while another study demonstrated that growth at an uncontrolled pH increased the survival of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus after spray-drying up to 10-fold, which was linked to overexpression of GroEL (20). A comparison of these data indicated that although GroESL plays a major role in the survival of L. paracasei NFBC 338 during exposure to stress, it is part of a wider arsenal of mechanisms (5). While we demonstrated that GroESL overproduction results in some protection during drying, the global consequences of overproduction were not studied. For example, GroESL overproduction can influence hrcA-regulated genes, thus reducing the expression of key proteins, such as DnaK (15). Furthermore, Tomas et al. (26) demonstrated that global expression patterns were altered following GroESL overexpression.

FIG. 1.

(a) Survival of L. paracasei NFBC 338 spray-dried in the presence of RSM (20%, wt/vol) at outlet temperatures of 95 to 100°C. Powders were formulated with cultures containing pGRO2 or pMSP3535. Powders were pour plated in MRS (open bars) and MRS containing NaCl (5%, wt/vol) (shaded bars). (b) Survival of L. paracasei NFBC 338 freeze-dried in the presence of RSM (20%, wt/vol) at outlet temperatures of 95 to 100°C. Powders were formulated with cultures containing pGRO2 or pMSP3535. Powders were pour plated in MRS (open bars) and MRS containing NaCl (5%, wt/vol) (shaded bars). The results are the means of triplicate drying trials, and the standard deviations are indicated by the error bars.

The sensitivity of dried cultures to NaCl, which was used as an indicator of cellular damage, was determined before and after processing as previously described (8). It was apparent that greater cell damage occurred in the control cultures (82% of the survivors exhibited sensitivity) than in the GroESL-overproducing cultures (only 1.5% of the cultures exhibited sensitivity) during spray-drying (Fig. 1a).

To assess the significance of GroESL overproduction on probiotic survival during low-temperature processing, cultures were grown as described previously (5), centrifuged, suspended in RSM (20%, wt/vol) to a final density of 1.5 × 109 to 2.5 × 109 CFU g−1, and freeze-dried. A laboratory-scale freeze-dryer (Edwards Modulyo, Crawley, Sussex, England) was used to process shell frozen samples at a constant temperature of −48°C and a vacuum pressure of 1.33 × 103 mbar for 16 h. Cultures overproducing GroESL exhibited 36.6% survival following freeze-drying (and produced powders containing 5.5 × 108 CFU g−1), compared with the approximately 22.2% survival of control cultures (which yielded powders containing 4 × 108 CFU g−1) (Fig. 1b). Similar results were obtained by Walker et al. (28) when Lactobacillus johnsonii was exposed to a heat shock at a temperature at which GroESL expression was highest (55°C for 45 min) prior to freezing at −20°C for 7 days. Interestingly, expression of small heat shock proteins during exposure to cold has been reported for Lactobacillus plantarum, suggesting that there is a link between chaperone induction and cold stress (21, 22). It has been reported that GroESL is responsible for low-temperature growth and mRNA stability in Escherichia coli (7, 9), which may explain the protective functions associated with GroESL overproduction during freeze-drying. L. paracasei NFBC 338 survived freeze-drying better than it survived spray-drying, as observed previously for other lactic acid bacteria (24). The greater losses during spray-drying were associated with the effects of thermal inactivation (25). Furthermore, 31% of probiotic survivors overproducing GroESL exhibited increased sensitivity to NaCl, while 62% of control cultures had process-associated injuries (Fig. 1b). Surprisingly, the NaCl susceptibility of the GroESL-overproducing culture was higher following freeze-drying than following spray-drying. While the milder processing conditions encountered during freeze-drying would be expected to cause less damage than spray-drying, it may be that the time of exposure (i.e., the residence time in the freeze-dryer [16 h] compared with the residence time in the spray-dryer [1.0 to 1.5 s]) led to increased salt sensitivity.

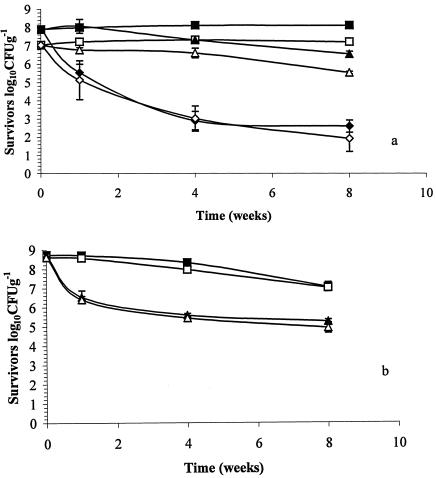

Following spray-drying, all powders were placed into polyethylene bags and stored at 4 to 37°C for 8 weeks under ambient atmospheric conditions, and the probiotic viability was assessed to establish whether overexpression of GroESL contributed to protection during storage. The viabilities of probiotic L. paracasei NFBC 338 cultures were initially 8.03 × 107 CFU g−1 and 1.20 × 107 CFU g−1 for GroESL-overproducing cultures and controls, respectively. At 4°C the viability of control or GroESL-overexpressing L. paracasei NFBC 338 remained stable for 8 weeks, while cultures stored at 15°C were less stable and the viabilities of powders containing GroESL-overproducing cultures and controls decreased 21- and 33-fold, respectively (Fig. 2a). At 37°C, dramatic losses were observed in both probiotic cultures, and the levels of L. paracasei NFBC 338 overproducing GroESL and the control decreased 165,000- and 58,000-fold, respectively, during the 8 weeks of storage (Fig. 2a).

FIG. 2.

(a) Survival of spray-dried L. paracasei NFBC 338 during storage of powder at 4°C (▪ and □), 15°C (▴ and ▵), and 37°C (⧫ and ⋄). The solid symbols indicate powders prepared with cultures containing pGRO2, while the open symbols indicate powders prepared with cultures containing pMSP3535. (b) Survival of freeze-dried L. paracasei NFBC 338 during storage of powder at 20°C (▪ and □) and 37°C (▴ and ▵). The solid symbols indicate powders prepared with cultures containing pGRO2, while the open symbols indicate powders prepared with cultures containing pMSP3535. The results are the means of triplicate drying trials, and the standard deviations are indicated by the error bars.

Freeze-dried powders were stored at 20 and 37°C as described above, and the viability of L. paracasei NFBC 338 was assessed for 8 weeks. Previously, we showed that L. paracasei NFBC 338 was stable at 4 and 15°C (4); hence, we used higher storage temperatures. Viable populations containing 5.5 × 108 CFU g−1 for GroESL-overproducing cultures and 4 × 108 CFU g−1 for controls were present in freeze-dried powders on day 0 of storage, and the viabilities remained high in powders stored at 20°C; there were 38- and 35-fold decreases in the viabilities of the GroESL-overproducing and control cultures, respectively, over 8 weeks (Fig. 2b). However, as described above for spray-dried powders, the decreases in viability were much greater following storage at 37°C, and approximately 3,000-fold decreases were observed for both cultures. It was apparent that freeze-dried cultures were more stable during high-temperature storage than spray-dried cultures, an observation that was in agreement with a previous study (29). The data also indicated that GroESL overproduction did not stabilize L. paracasei NFBC 338 during storage in either the freeze-dried or spray-dried form. It has been reported that the lipid membrane may be the principal site of damage during storage of spray-dried and freeze-dried powders due to lipid oxidation (3, 23).

The moisture contents of powders were determined as described in the International Dairy Federation bulletin (11). Spray-dried powders had moisture contents of 2.20 to 2.30% H2O g−1, while freeze-dried powders manufactured in this study contained 3.26 to 3.31% H2O g−1. The water activity (aw) in the dried powders was measured in duplicate using an Aqualab model series 3 (Decagon Devices Inc., Pullman, WA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The aw for spray-dried powders was 0.373, while freeze-dried powders produced in this study had an aw of 0.320; these values were within the range (0.28 to 0.65) considered suitable for survival of bacterial populations dried in milk-based powders (14).

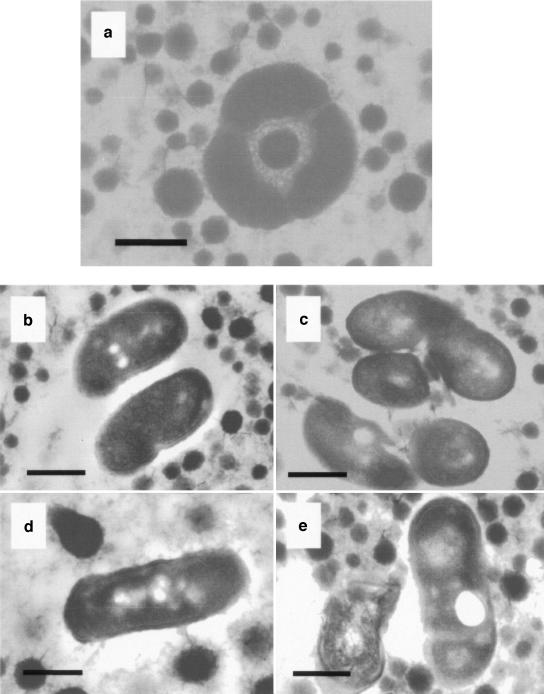

Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), it was apparent that the probiotic lactobacilli present in both spray-dried and freeze-dried powders were in close contact, and there were indications of bacteria huddled together. This phenomenon was seen in both GroESL-overproducing L. paracasei NFBC 338 (Fig. 3a) and controls (data not shown). The GroESL-overproducing cultures appeared to be more robust and intact following drying (Fig. 3b and d) than the control cultures (Fig. 3c and e), and damage was observed in control cells, particularly the broken cell shown in Fig. 3e. TEM has been used previously to show the effects of salt and nisin on the integrity of lactobacilli (2, 16).

FIG. 3.

(a and b) TEM images of spray-dried L. paracasei NFBC 338 containing pGRO2. (c) TEM image of spray-dried L. paracasei NFBC 338 containing pMSP3535. (d and e) TEM images of freeze-dried L. paracasei NFBC 338 containing pGRO2 (d) and pMSP3535 (e). Magnification, ×60,000. Bars = 0.5 μm.

This study demonstrated that GroESL overproduction in L. paracasei NFBC 338 resulted in improved performance during spray- and freeze-drying but did not contribute to enhanced survival of probiotic cultures during storage in the powder form. While undoubtedly multiple mechanisms are involved in stress tolerance in lactobacilli, our data demonstrate that the heat chaperones GroESL exert a dominant phenotype with regard to strain performance during drying.

Acknowledgments

B. M. Corcoran received a Teagasc Walsh Fellowship. This work was funded by the Irish Government under National Development Plan 2000-2006, by the European Research and Development Fund, by Science Foundation Ireland, and by EU project QLK1-CT-2000-30042.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ananta, E., S.-E. Birkeland, B. Corcoran, G. Fitzgerald, S. Hinz, A. Klijn, J. Matto, A. Mercernier, U. Nilsson, M. Nyman, E. O'Sullivan, S. Parche, N. Rautonen, R. P. Ross, M. Saarela, C. Stanton, U. Stahl, T. Soumalainen, J.-P. Vincken, I. Virkajarvi, F. Voragen, J. Wesenfeld, R. Wouters, and D. Knorr. 2004. Processing effects on the nutritional advancement of probiotics and prebiotics. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 16:114-124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benech, R. O., E. E. Kheadr, C. Lacroix, and I. Fliss. 2002. Antibacterial activities of nisin Z encapsulated in liposomes or produced in situ by mixed culture during cheddar cheese ripening. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 68:5607-5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro, H. P., P. M. Teixeira, and R. Kirby. 1997. Evidence of membrance damage in Lactobacillus bulgaricus following freeze drying. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82:87-94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desmond, C., B. M. Corcoran, C. Stanton, G. Fitzgerald, and R. P. Ross. 2005. Development of dairy-based functional foods containing probiotics and prebiotics. Aus. J. Dairy Technol. 60:121-126. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desmond, C., G. F. Fitzgerald, C. Stanton, and R. P. Ross. 2004. Improved stress tolerance of GroESL-overproducing Lactococcus lactis and probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei NFBC 338. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5929-5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desmond, C., C. Stanton, G. F. Fitzgerald, K. Collins, and R. P. Ross. 2001. Environmental adaptation of probiotic lactobacilli towards improvement of performance during spray drying. Int. Dairy J. 11:801-808. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fayet, O., T. Ziegelhoffer, and C. Georgopoulos. 1989. The groES and groEL heat shock gene products of Escherichia coli are essential for bacterial growth at all temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 171:1379-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardiner, G. E., E. O'Sullivan, J. Kelly, M. A. Auty, G. F. Fitzgerald, J. K. Collins, R. P. Ross, and C. Stanton. 2000. Comparative survival rates of human-derived probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei and L. salivarius strains during heat treatment and spray drying. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2605-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgellis, D., B. Sohlberg, F. U. Hartl, and A. von Gabain. 1995. Identification of GroEL as a constituent of an mRNA-protection complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1259-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwich, A. L., K. B. Low, W. A. Fenton, I. N. Hirshfield, and K. Furtak. 1993. Folding in vivo of bacterial cytoplasmic proteins: role of GroEL. Cell 74:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Dairy Federation. 1993. Dried milk and dried cream. Determination of water content. International Dairy Federation standard 26A. International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium.

- 12.Johnson, J. A. C., and M. R. Etzel. 1993. Inactivation of lactic acid bacteria during spray drying. AIChE Symp. Ser. 89:98-107. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalliomaki, M., S. Salminen, H. Arvilommi, P. Kero, P. Koskinen, and E. Isolauri. 2001. Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 357:1076-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosanke, J. W., R. M. Osburn, G. I. Shuppe, and R. S. Smith. 1992. Slow rehydration improves the recovery of dried bacterial populations. Can. J. Microbiol. 38:520-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mogk, A., G. Homuth, C. Scholz, L. Kim, F. X. Schmid, and W. Schumann. 1997. The GroE chaperonin machine is a major modulator of the CIRCE heat shock regulon of Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 16:4579-4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piuri, M., C. Sanchez-Rivas, and S. M. Ruzal. 2005. Cell wall modifications during osmotic stress in Lactobacillus casei. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:84-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rye, H. S., A. M. Roseman, S. Chen, K. Furtak, W. A. Fenton, H. R. Saibil, and A. L. Horwich. 1999. GroEL-GroES cycling: ATP and nonnative polypeptide direct alternation of folding-active rings. Cell 97:325-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saavedra, J. M., N. A. Bauman, I. Oung, J. A. Perman, and R. H. Yolken. 1994. Feeding of Bifidobacterium bifidum and Streptococcus thermophilus to infants in hospital for prevention of diarrhoea and shedding of rotavirus. Lancet 344:1046-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan, V. M., R. D. Sleator, G. F. Fitzgerald, and C. Hill. 2006. Heterologous expression of BetL, a betaine uptake system, enhances the stress tolerance of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2170-2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva, J., A. S. Carvalho, R. Ferreria, R. Vittorino, F. Amado, P. Domingues, P. Teixeira, and P. A. Gibbs. 2005. Effect of the pH of growth on the survival of Lactobacillus bulgaricus subsp. bulgaricus to stress conditions during drying. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:775-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spano, G., L. Beneduce, C. Perrotta, and S. Massa. 2005. Cloning and characterization of the hsp 18.55 gene, a new member of the small heat shock gene family isolated from wine Lactobacillus plantarum. Res. Microbiol. 156:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spano, G., V. Capozzi, A. Vernile, and S. Massa. 2004. Cloning, molecular characterization and expression analysis of two small heat shock genes isolated from wine Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:774-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira, P., H. Castro, and R. Kirby. 1996. Evidence of membrane lipid oxidation of spray-dried Lactobacillus bulgaricus during storage. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 22:34-38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.To, B. C. S., and M. R. Etzel. 1997. Spray drying, freeze drying or freezing of three different lactic acid bacteria species. J. Food Sci. 62:576-578. [Google Scholar]

- 25.To, B. C. S., and M. R. Etzel. 1997. Survival of Brevibacterium linens (ATCC 9174) after spray drying, freeze drying or freezing. J. Food Sci. 62:167-170. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomas, C. A., N. E. Welker, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2003. Overexpression of groESL in Clostridium acetobutylicum results in increased solvent production and tolerance, prolonged metabolism, and changes in the cell's transcriptional program. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4951-4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Guchte, M., P. Serror, C. Chervaux, T. Smokvina, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Maguin. 2002. Stress responses in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:187-216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker, D. C., H. S. Girgis, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1999. The groESL chaperone operon of Lactobacillus johnsonii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3033-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Y. C., R. C. Yu, and C. C. Chou. 2004. Viability of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria in fermented soymilk after drying, subsequent rehydration and storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 93:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]